Introduction

Silesia is a historical region that is chiefly located in south-western Poland (Figure 1). Until the end of the twelfth century, it was sparsely developed and distant from major political centres; however, in the thirteenth century, the region flourished extraordinarily. The most significant factor in this rapid prosperity was the action taken by local princes to intensify the settlement network. Numerous villages and more than a hundred new towns were founded, including in the barely accessible Sudetes mountains. As early as the thirteenth century, a distinctive urban model was formed, whose layout comprised elements which originated in other regions but which were put together originally and consistently.

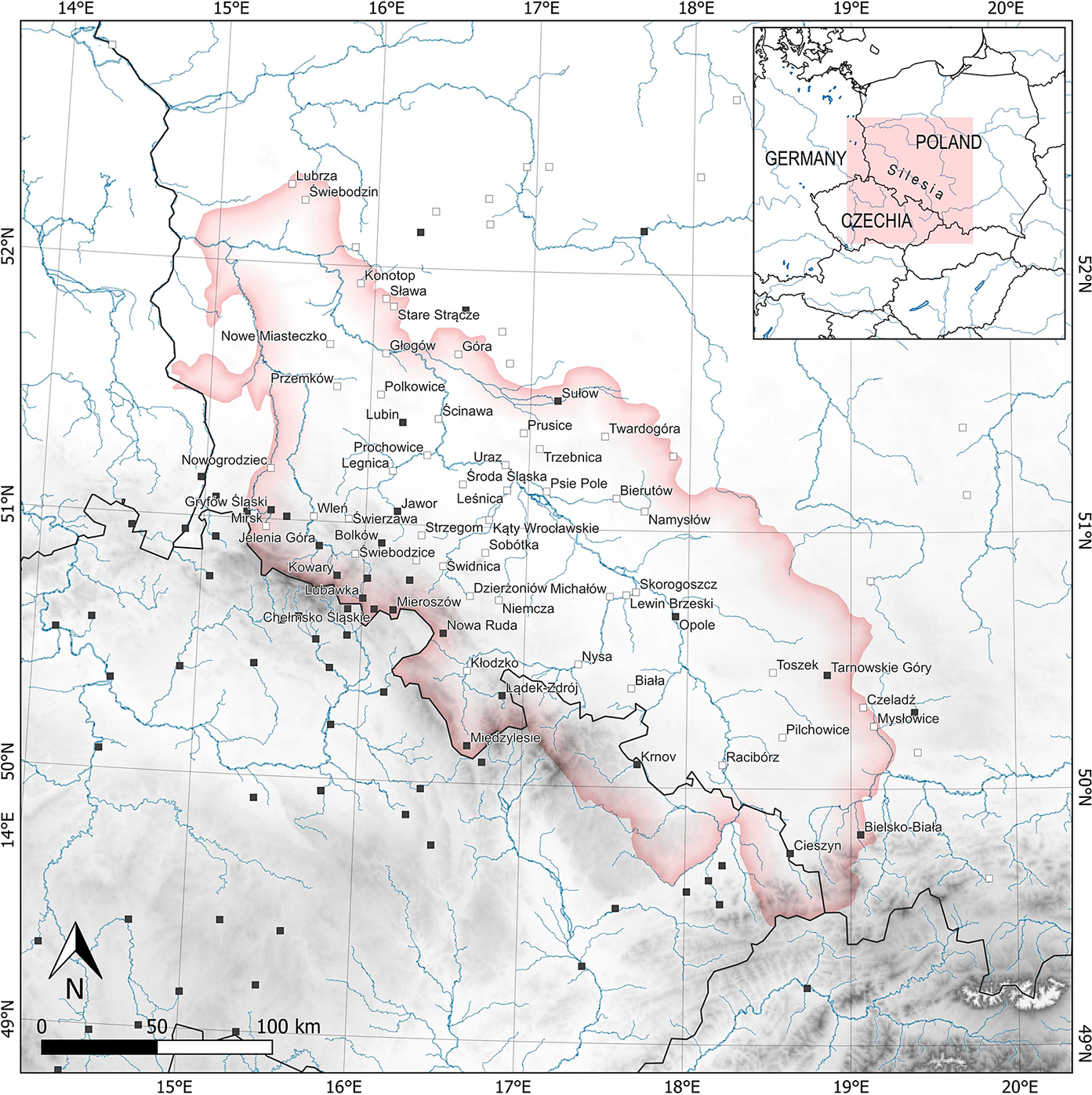

Figure 1. Map showing the location of the historic region of Silesia and the Kłodzko Land. The black squares show the towns in which arcaded houses have survived to the present day, the white squares show the towns in which the existence of arcades is confirmed by historical sources. The names of towns within Silesia and the Kłodzko Land are included. Data: author, cartographic design: Maksym Mackiewicz.

Among the emerging architectural features, arcades may have been introduced early on – an often underestimated yet crucial element in the organization of economic activity, communication and aesthetics. Arcaded houses were mentioned in Silesian written sources as early as the fourteenth century and became an important element of the region’s cultural landscape. Their construction peaked in the eighteenth century, appearing in towns and villages across the region.

Silesia was one of the many European regions where arcaded houses were frequently built, making it part of an extensive zone featuring this architectural phenomenon. Arcaded houses can still be found in western Ukraine, southern Poland, the Czech Republic, southern Germany, Switzerland, northern Italy, southern France and Spain. Nevertheless, this architectural solution was absent in a significant part of the continent, and its distribution formed a relatively compact cluster with a few exceptions. This makes Silesian houses part of a specific architectural zone and warrants interpretation in a broader European context.

This article discusses the location of arcades within the Silesian urban environment, the timing and circumstances surrounding their introduction and their impact on urban layouts, including the context in which they were removed. It aims to place the Silesian case within a broader geographical context and contribute to advancing the study of urban planning in European towns with arcaded architecture.

Arcades are frequently overlooked by scholars of urban history, as evidenced by the underdeveloped research on this subject. Initial studies from the nineteenth century mostly considered arcades an important feature of rural landscapes, focusing on types and origins. At the beginning of the twentieth century, arcaded houses in cities received increasing attention from scholars; however, their broader urban context was rarely addressed.Footnote 1 H. Markwalder’s study of Swiss towns was among the earliest to provide valuable data on the subject. It examined the context of the introduction of front arcades into urban structures, as well as the rights and obligations associated with their presence.Footnote 2

Key studies have been published in the last two decades, with several on arcaded houses in cities in northern Italy, including the well-known case of Bologna, primarily by F. Bocchi and R. Smurra.Footnote 3 These researchers initiated an unprecedented joint publication, compiling articles on the topic written by leading scholars from several European countries.Footnote 4 However, some regions with outstanding examples of arcaded architecture, such as Bohemia and Bavaria, have been neglected. Prinzipalmarkt in Münster is the only site to be systematically analysed in a study published in 2001.Footnote 5 Consequently, the relationship between the arcades in Silesia and its border regions, Bohemia and Lusatia, could not be investigated.

Some researchers have addressed the subject of arcades in Silesia. M. Chorowska and C. Lasota analysed the subject of arcades and stoops but focused only on larger towns in the region (Wrocław, Głogów and Świdnica).Footnote 6 In 2004, K. Dumała described the origins of arcaded houses, including those in Silesia.Footnote 7 In recent years, I have addressed this issue several times, adding my observations to previously discussed questions and examining the ideological approach in earlier studies on arcades and exploring Silesian arcades in a broader European context.Footnote 8

In this article, owing to the lack of comparable sources for the entire research area of Silesia and the Kłodzko Land, various methods were employed; a comprehensive view on the issue was obtained by combining different data. Historical written sources, primarily those collected in editions published in the nineteenth century, served as the foundation of this research.Footnote 9 Unfortunately, the number of preserved medieval and early modern sources is limited. Therefore, additional data were obtained through field studies and architectural research on preserved examples of arcaded houses, including cellars. Traditional methods of collecting and analysing visual materials, such as historical drawings, graphics, photographs and maps, were also employed. This approach was crucial for reconstructing parts of towns that had been destroyed or significantly altered. Silesia and the Kłodzko Land, which have been interlinked for centuries, are the starting points of this research. However, the European context is also discussed, which enables a comparison of solutions, complements our insufficient knowledge and – owing to the poor availability of sources – is a type of reconstruction. Comparable data were obtained through a literature review and by conducting field research in other regions of Poland, as well as the Czech Republic, Bavaria, Switzerland, northern Italy and southern France. Notably, this study is one of the first comprehensive approaches to this topic.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The first section provides an overview of the characteristic urban layout that distinguishes Silesian towns, describing typical areas where arcaded houses appeared. The next section discusses the introduction and spread of arcades in Silesia, analysing all preserved examples and, based on historical and iconographical sources, identifying towns where arcades once existed. The third section investigates the timing and circumstances surrounding the introduction of arcades into the urban structure. Owing to limited sources, the more thoroughly documented processes from southern France, Switzerland and Italy serve as a base for observations. The next section elucidates the consequences of introducing and removing arcaded passages, which was always subject to approval by town authorities or property owners and was therefore intended to serve a specific purpose. This element had significant consequences for the townspeople and the urban structure, as it disrupted the boundaries between individual properties and the whole community. The final section outlines the major findings of the study.

Arcades in the town structures of Silesia and the Kłodzko Land

Towns in Silesia were established at the beginning of the thirteenth century, many in undeveloped or sparsely populated areas. The only exceptions were the old early medieval strongholds such as Wrocław, Legnica, Głogów, Niemcza and Opole. The earliest confirmed foundation charter was granted in 1211, assigning urban privileges to Złotoryja that mirrored those of German charters.Footnote 10 The founding of towns became particularly intense in the mid-thirteenth century, with Silesia eventually harbouring over a hundred urban centres.Footnote 11 The local population and a large share of newcomers from the west and south-west inhabited the new settlements. Only a few documents connected to the founding of those towns are available, and they rarely mention the spatial organization, buildings or operational information in the first generation of settlers.Footnote 12 Municipal records did not emerge until the fourteenth century; these reveal features of the urban topography and facilities, albeit in a highly fragmented form.

Silesian cities were generally assigned a characteristic urban layout – often the only surviving witness to their foundation. Its key feature was a relatively regular orthogonal street grid with a quadrangular market square at its centre. Except for the smallest towns, most urban centres were surrounded by oval-shaped walls. This caused the market square and surrounding building quarters to exhibit remarkable regularity, with any irregularities becoming more pronounced closer to the walls.

The layout of the main streets varied: the simplest solution was a system of streets branching out at the gate and leading to the corners of the main square. In the most elaborate version, two streets extended from each corner of the square, with additional streets cutting through the blocks on the square’s longer side. The system was complemented by narrow streets that provided internal connections. Sometimes, additional auxiliary squares were carved out, such as the Cow Market in Bystrzyca Kłodzka and the Horse Market in Jawor.

Regarding the location of the most important public buildings, the seats of municipal authorities and commercial buildings were placed at the centre of the main square. The parish church was usually located in a building quarter adjacent to the corner of the square or one block away. Castles and monasteries were often located near outer walls. However, a few deviations from these model layouts featured an extended market framed by streets meeting at the town gates (for example, Złotoryja, Środa Śląska, Lubomierz).

Towns arranged according to this pattern were divided into quarters, with plots built with houses, some of which featured front arcades in the fourteenth century (discussed below). Arcaded buildings were generally erected in the centres of towns, specifically market squares, where space could be occupied without impeding traffic. These prime locations, often the political heart of the town, provided arcaded homes for the town’s financial elites, typically originating from the merchant class. Therefore, owners often used arcades commercially or rented them out during fairs. In early modern Świdnica and Jelenia Góra, specific sections of the arcades were named after the type of goods traded there, such as the Hops and Wool Arcades in Świdnica and the Cloth, Furrier, Butter, or Hose Arcades in Jelenia Góra.Footnote 13

In the area studied in this article, arcaded houses have survived in the main squares (in Bielsko-Biała, Bolków, Chełmsko Śląskie, Cieszyn, Gryfów Śląski, Jawor, Jelenia Góra, Kamienna Góra, Lądek-Zdrój, Leśna, Lubawka, Lubomierz, Mieroszów, Nowa Ruda, Sławków, Sulików, Sułów, Tarnowskie Góry and Wałbrzych), where the urban financial and political elites typically lived (Figure 2). Their economic power allowed them to use expensive and durable building materials earlier than the citizens inhabiting other parts of the town. Consequently, the market square houses preserved their features, regardless of their architectural form. Perhaps this is why we primarily associate arcaded buildings with market squares. Those in less prominent locations, likely built from wood, have perished and been forgotten.

Figure 2. The arcaded houses at the market square in Jawor (top) and Chełmsko Śląskie (bottom).

In some cases, arcaded buildings extended beyond the main squares. Arcade passages along the streets typically led from the town gates to the main squares, effectively standardizing the town’s main traffic routes. The town of Kamienna Góra has the most extensive arcade passages preserved today. In the fourteenth century, arcades stretched along the main streets in Świdnica: Dąbrowskiego, św. Anny and Świdnicka.Footnote 14 Werner’s eighteenth-century view of Strzegom shows arcades in more peripheral zones (Figure 3). Webergasse was once a craftsmen’s street, as indicated by its name, Tkacka (Weavers’ Street). Strzegom’s weaving industry flourished in the sixteenth century. In 1525, there were 88 masters and 12 masters’ widows, and in 1570, there were 200 clothiers. In 1547, the clothiers’ guild decided to purchase a house in Webergasse,Footnote 15 which was authorized by the town council because the guild did not have a seat.Footnote 16 The location of the guild house most likely reflects the concentration of clothiers in this area. It is possible that they favoured arcaded houses as the most suitable for their trade. This was also apparent in Winchester, England, where arcades stretching along the High Street were initially associated with clothiers. Derek Keene theorized that the arcade zone served as a sheltered space from bad weather while allowing merchants to view the colour and weave of fabrics in daylight.Footnote 17

Figure 3. Perspective view of Strzegom showing widespread arcaded buildings. F.B. Werner, Topographia Silesiae…, vol. III, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, ref. XVII, HA, Rep. 135, Nr. 526-2, p. 337, excerpt.

Strzegom is not the only Silesian example of the connection between arcades and textile crafts. A 1386 document containing regulations for the stallholders of Jawor specifies that all the town’s craftsmen making silk products had the right to sell them individually in their workshops and under arcades on market days.Footnote 18 This relationship is also confirmed by much later building complexes, such as the string of arcaded houses in Chełmsko Śląskie, 13–23 Sądecka Street. This compact building cluster, known as the ‘12 Apostles’, was a gabled weaver’s house built in 1707, located east of the town centre (Figure 4).Footnote 19 On the northern side of the same town, by the former yarn market on Kamiennogórska Street, at No. 21, the last house from another complex of weavers’ houses, the so-called ‘Seven Brothers’, built in the eighteenth century still stands.Footnote 20

Figure 4. Chełmsko Śląskie, weavers’ houses, the so-called ‘12 Apostles’.

Eighteenth-century houses, traditionally associated with weavers, were also preserved in Międzylesie. The last two, located on Sobieskiego Street, are remnants of what were once rows of such buildings. However, while the ‘12 Apostles’ complex in Chełmsko Śląskie was built as a unified structure, the houses in Międzylesie were built independently, as private houses-cum-workshops. All preserved Baroque buildings of this type likely represent a continuation of a tradition originating in the Middle Ages and the early modern period, as demonstrated by the case of Strzegom.

Along the present-day Nadrzeczna Street in Nowa Ruda, arcaded houses create a waterfront facing the Włodzica River, and are probably the most unusually located houses in the region (Figure 5). Currently, the Włodzica River flows through a canal constructed to manage frequent floods. When redrawing the view of the town from 1736, the local printmaker and publisher Pompejus described a section of Piastów Street, built on both sides, as Schusterlauben – shoemakers’ arcades and the houses on Nadrzeczna Street as Oberlauben. Footnote 21 On the other side of the river, along the present-day Łukowa Street in the Marien-Viertel area, houses also face the river. It appears that the location of arcades was directly associated with access to water, which was necessary for activities such as tanning. Houses along the Czarna Oława River in Wrocław are compelling examples. Their connection to water is attested to in historical iconography. A compact row of houses along a small watercourse outside of the town walls in Ząbkowice Śląskie was described by F.B. Werner as ‘ünter den gärbern’. The houses in Nowa Ruda’s Schusterlauben may have similarly been used by craftsmen practising leather processing. Crafts that were onerous for the residents frequently moved out of the town centres, which explains the location of the Schusterlauben in Nowa Ruda.

Figure 5. Nowa Ruda, arcaded houses on the Włodzica River, Herder-Institut archive, sig. 129729.

As previously discussed, arcades were primarily located in the most important areas of towns. In Silesia and the Kłodzko Land, these were typically the main squares. Thus, arcaded houses became associated with urban financial and political elites, who used them commercially and for leasing. Occasionally, the arcades extended to other parts of the town, particularly along major streets, as is demonstrated in Strzegom. The peripheral communities of craftsmen working in textiles and leather processing were not only established outside the central locations, but also encompassed arcaded houses. Access to water needed for production may have influenced the regionally unique spatial solution of building river-facing arcades in Nowa Ruda.

Introduction and spread of arcades

The towns mentioned above were not the only places where arcades were constructed. As my studies indicate, arcaded houses survived in 22 towns in Silesia and the Kłodzko Land. Based on written sources and mostly eighteenth-century iconography, they were present in at least 45 additional centres,Footnote 22 many of which were located in Silesia’s mountainous zone in the Sudetes (see Figure 1). Whether the number of centres with arcades established during the Baroque period reflects an earlier trend or whether the Baroque era saw an exceptional rise in the popularity of arcaded houses remains unclear. This uncertainty highlights a methodological difficulty: how to determine whether arcades in medieval towns were envisaged at the earliest stage of planning and surveying newly founded settlements.

Unfortunately, the surviving documents relating to the founding of Silesia’s towns fail to address the issue of their internal arrangements. More detailed records were made by municipal chancelleries, which began operating only in the early fourteenth century. Therefore, it is possible to identify towns featuring arcaded houses at that time; however, sources that might reveal whether arcaded houses existed in these centres from the start and the conditions for their introduction are unclear.

Examples of the formal adoption of arcaded houses in towns can only be observed in centres which, despite being geographically distant, displayed certain similarities to Silesian towns. South-western France – particularly New Aquitaine and Occitania, with towns known as bastides – closely resembles the characteristics of towns founded in Silesia. In both areas, a significant number of new centres were established over a relatively short period (more than 300 bastides between 1220 and 1340).Footnote 23 The foundation of towns was intended to fill gaps in the existing urban network and strengthen the territory’s economic position. Both regions are also characterized by a regular town design, with the market square being the most important public space. Crucially, for our argument, arcades were widely used in these towns and many of them have survived until today, mostly in central squares. There were 86 bastides with surviving arcades in the nineteenth century.Footnote 24

The earliest written references confirming the existence of arcades in bastides come from charters granted to the towns of Monségur (1265 and 1267), Sauveterre (1281 and 1283) and Créon (1317),Footnote 25 which mention the canopies and porches in front of the market square. Notably, just four years after Villefranche-de-Rouergue was granted its municipal charter (likely in 1256), the owners of plots in the town’s central square asked for permission to construct ‘covered passages’ at the front of their properties.Footnote 26 However, the nature of these structures is uncertain.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, this case reveals that the municipal charter did not include permission to create such accessory structures, that an intrusion into public spaces required official approval and that the residents desired these structures. The situation was different for Créon, an English royal foundation. A 1315 document defining its municipal rights states that houses around the square might feature ambana et perjecta et stillicidia. Footnote 28 Stillicidia were canopies placed over the house front, perjecta were forward-extending upper house floors and ambana were roofed structures attached to the ground floor. These features were not obligatory, but homeowners were permitted to build and use them at no additional cost.Footnote 29

Thus, the privilege of creating such structures at the beginning of the bastides’ existence was not a rule. Perhaps, the chronological difference between the two documents is significant. One might assume that after half a century of arranging towns, it was necessary to address the issue of additional structures on house fronts in municipal charters. The possibility, rather than the obligation, of building frontal structures may also suggest that arcades, likely to occupy public spaces when introduced, were not considered at the town-planning stage.

Swiss centres, mainly those founded in the twelfth century by the Zähringer family, are also interesting in this regard. Although differing from the Silesian centres chronologically and morphologically, they are described in well-preserved, early and detailed historical sources that, to some extent, reflect the processes later observed in Central and Eastern Europe. Despite their early beginnings, centres such as Bern, Thun, Freiburg and Lausanne did not receive codified municipal charters until the thirteenth century. These and other thirteenth-century documents, as well as later chronicles referring to that time, provided the earliest evidence of the use of arcades. The Chronicle of Bern mentions a town fire prior to 1286 and subsequent reconstruction with arches (bogen) ‘as before’.Footnote 30 This mention would prove that the town already had ‘arches’ before 1286, and that continuation of this tradition was considered appropriate. Freiburg’s municipal law of 1249 included an ordinance allowing every burgher to construct brick arches in front of their houses and build upon them.Footnote 31 Almost identical provisions can be found in Handfeste for Thun in 1264 and Burgdorf in 1273.Footnote 32 However, in Lausanne, trading benches in front of houses were allowed along the designated market street, provided they did not extend more than one foot into the street; however, building arcades was not allowed.Footnote 33 Thus, the documents do not testify to the original existence of arcades in the Zähringer towns. Regulations in the existing structures suggest that arcades gradually encroached on public spaces and became an area of concern for municipal authorities.

Intensive regulatory measures concerning arcades were implemented during the thirteenth century in Italian cities such as Verona and Bologna.Footnote 34 Hence, the thirteenth century across Europe was marked by efforts to regulate existing arcades. Thus, many of those structures were removed, as in Vicenza,Footnote 35 or, on the contrary, their construction was imposed on new developments, as in Bologna. Simultaneously, the needs of the inhabitants of towns founded in the thirteenth century (such as French bastides) were most likely addressed ad hoc by broadening the functionality of their houses and workshops. Towns founded slightly later during the fourteenth century may have had predetermined conditions for adding arcades.

At this point, let us return to Silesia and the Kłodzko Land and try to determine when arcaded houses were adopted in this region. In 1337, Duke Bolko II issued a document confirming the weavers’ existing rights while allowing them to sell whole cloth pieces stando sub lebys without any obstacles.Footnote 36 The term Lebys (Laube, in modern German) is a broad designation referring to various roofings, but in Silesia, it is strongly connected to burgher houses and specifically denotes arcades. Thus, weavers were permitted to trade while standing under an arcade, most likely in front of their houses. The document is vital for several reasons. First, it is the oldest known record confirming the existence of this architectural element in Silesian towns. Considering that the town was established in stages between 1241 and 1266, the arcades must have emerged very early, although we do not know whether the first generation of residents had already used them. Second, the document indicates the primary function of arcades, namely commerce. Textiles as traded goods are also significant because textile crafts were among the most important in Silesia.

During the 1380s, several references to arcades in Legnica were recorded. Some documents referred to arcades to distinguish individual properties (1380), while others described a brick arcade (1384);Footnote 37 however, the most informative document was an order issued in 1384, demanding the removal of the market square arcades.Footnote 38 All homeowners were ordered to remove arcades by bricking them up and incorporating the former passageways into their houses. No information about the reasons for this decision was provided but the fact that the arcades were bricked up suggests that lack of space in the square was not a problem. Aesthetic considerations may have played a role, as it was on this basis that gables were mandated after the Wrocław model.

Arcades were confirmed in Jawor before 1386. A copy of a document issued to Jawor’s stallholders stated that all manufacturers of curtains, silk strings and sacks or braids could, or even should, sell them in their workshops and under the arcades on market days.Footnote 39

In the fourteenth century, arcades were undoubtedly present in Świdnica, where they stretched along the market square house fronts and all broad streets.Footnote 40 Their distribution has been reconstructed based mainly on historical sources and the study of cellars, which may relate to arcades that are no longer extant. According to the written sources, the lower section of the northern frontage of Pułaskiego Street, mentioned in 1377, was customarily called the High Arcade (Hohe Löbe).Footnote 41

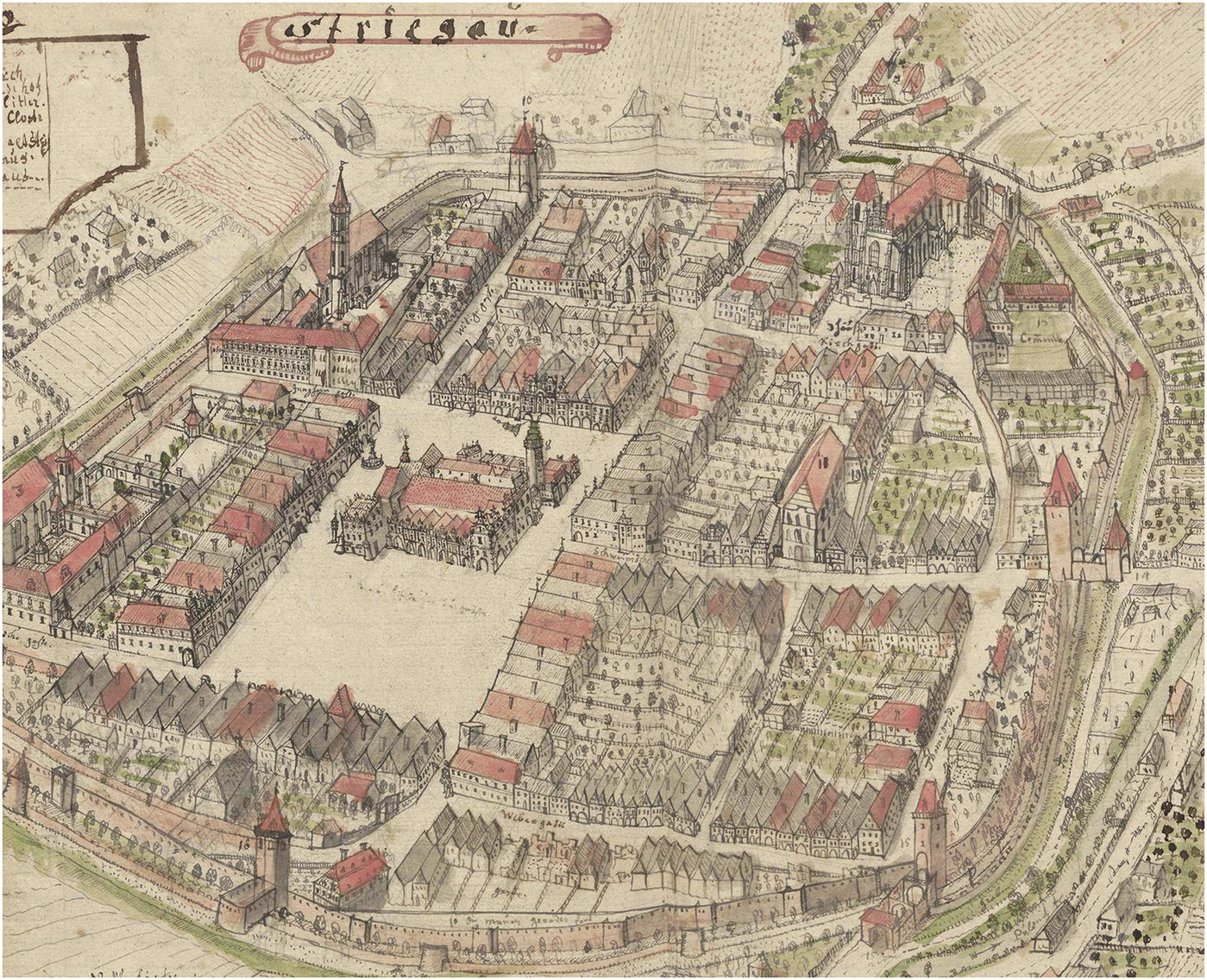

As demonstrated above, the roofing in front of Silesia’s burgher houses existed as early as the fourteenth century. By the fifteenth century, arcades were also present in Kłodzko, and in the following century, in Grodków and Lwówek Śląski.Footnote 42 The oldest preserved arcades date from the sixteenth century, specifically the Renaissance period (for example, in Jawor and Gryfów Śląski). However, an overwhelming majority of the arcades in the study area date back, at least in their external form, to the eighteenth century, when they became virtually ubiquitous. The oldest arcaded houses known from visual sources were in Strzegom (Figure 6). Based only on their external features, they were possibly built at the turn of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The sources cited above refer to existing structures, implying that they were built earlier. The case of Legnica shows that the temporal gap must have been significant because documents from the 1380s mention an order to demolish arcades, probably including brick ones.Footnote 43 The presence of the brick arcades implies that their construction followed an established tradition. Insufficient archaeological and architectural research prevents us from determining whether any medieval fabric is preserved in modern structures. Moreover, we cannot be sure that the European examples from the thirteenth century discussed above served as models for the introduction of arcades in Silesia.

Figure 6. The burgher houses at the market square in Strzegom. Third house from the left is the oldest known example of an arcaded house in Silesia. Herder-Institut archive, sig. 51183.

Arcades in towns and their impact on urban layout

The lack of relevant sources or results of invasive studies means that it is only possible to reconstruct the original urban layout by analysing the preserved spatial and architectural structures. As noted above, arcades in Silesia were preserved mainly around rectangular market squares. Their proportions differ from the elongated framed squares in Bohemia, Bavaria or Piedmont, which reflect French patterns and lead to differences in traffic dynamics. In those regions, the movement resembles linear traffic in street markets, whereas in Silesia, streets stream into the vortex-like pattern of the main square. Frontage lines were created to extend around the ends of the streets opening into the square. Sometimes, the houses extend forward, taking up the entire width of the arcade, as can be seen in Lądek Zdrój, Leśna or Wałbrzych. More commonly, however, this extension is about half the width of the arcade, which still allows a smooth entrance from the street into the covered passage (as in Bolków, Gryfów Śląski, Jawor and Lubawka). In these cases, the arcaded zone projects slightly deeper into the square than the building lines on the streets opening into the square. Sometimes, arcaded passages extend into neighbouring street sections, forming distinctive frontage bulges that are broader towards the middle of the square and narrower in the streets (as in Jelenia Góra) (Figure 7). The extent to which such a configuration was intentional or the result of a gradual encroachment across old plot boundaries is unclear.

Figure 7. Jelenia Góra, plan of the city centre made on the basis of a map showing arcaded houses before their demolition conducted in the 1960s and 1970s. Arrows mark the narrow entrances to the arcades extending into the market square.

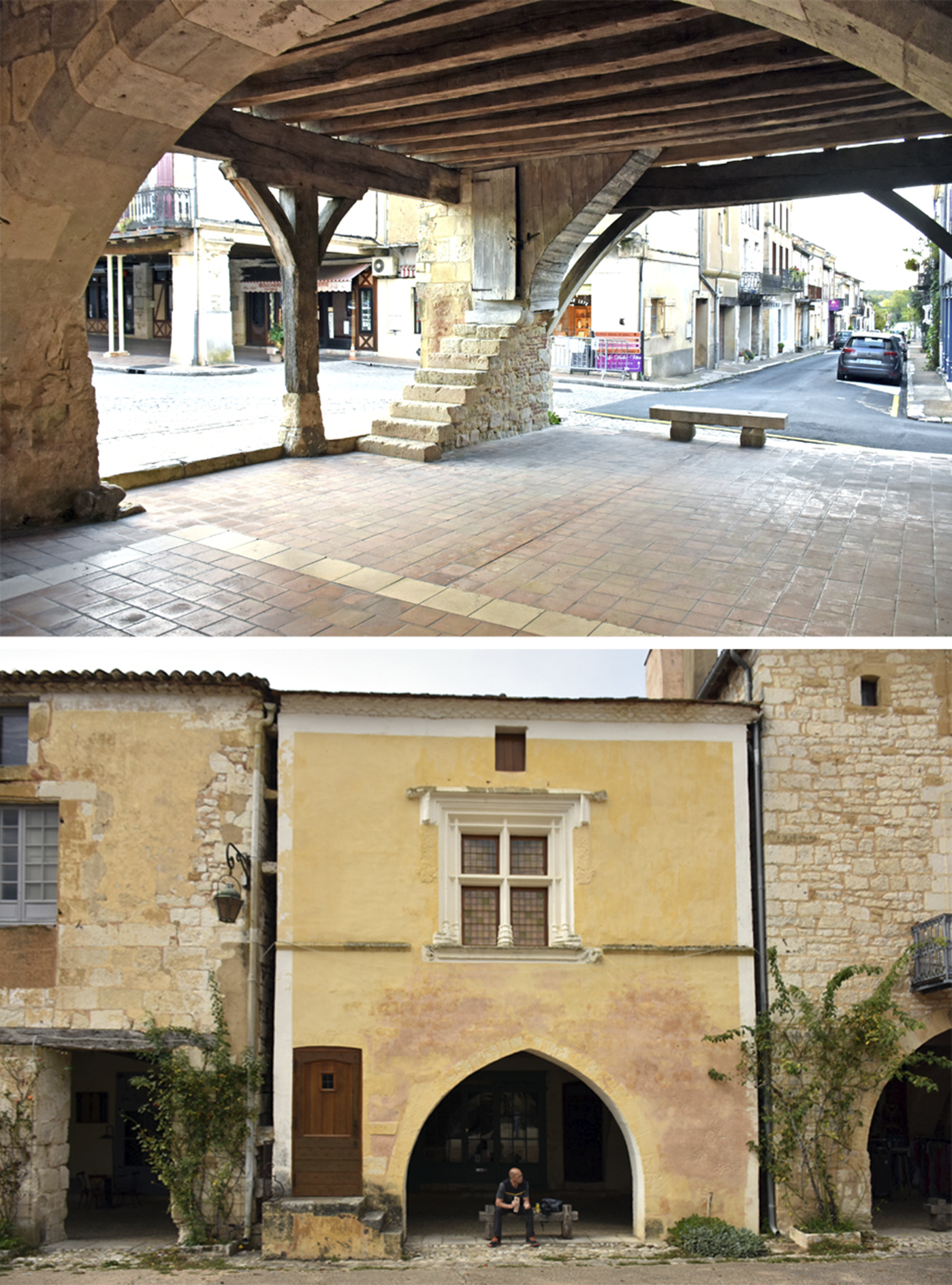

Extending the arcades into the square and narrowing them along the streets prevented the square corners from being blocked. However, in Silesia, even when the arcades extended forward by their full width, the entrances to the market square remained clear. This prevented the arcade corners from creating gateways, as frequently occurred in bastides (e.g. Lauzerte, Monpazier, Monflanquin, Castelnau-de-Montmiral and Lisle-sur-Tarn) (Figure 8). The only known Silesian instance of a blocked square corner may be found in Chełmsko Śląskie, as evidenced by the stepped, most likely secondarily ‘cut out’ north-western market square entrance and the built-up south-western corner. This last corner was closed by arcades after the construction of a new road in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 44 At this point, it is difficult to determine whether the town layouts in Silesia and the Kłodzko Land were designed to keep the main square entrances clear even after adding arcades. Another possibility is that later regulations unblocked the square corners and defined new plot borders. In any case, the distinct configuration of arcades meeting at the corners is a feature characteristic of only French bastides and perhaps is a unique aspect of local urban planning.

Figure 8. Examples of arcaded houses adjoining each other at the corners of markets squares: Monpazier (top), Lauzerte (bottom).

Frontages that partially cover the breadth of streets entering the market square may indicate that arcades were once present, even if they no longer exist. This would have happened if a new house without arcades was erected on the plot where the arcaded space had once stood or when an older house incorporated a bricked-up arcade passage. An example of such a process can be found in the historic centre of Legnica. Historical cartography allows us to observe the probable consequences of an order from 1384 to brick up the main square arcades. Consequently, the frontages in the square noticeably protruded, narrowing the terminal sections of the streets leading into the square (Figure 9). Owing to the demolition of houses during World War II, it is now impossible to determine whether the remains of the old arcades were traceable. In other towns, such as Mirsk, Chełmsko Śląskie and Gryfów Śląski, parts of the former, secondarily bricked-up arcades were preserved (Figure 10). Bricking up the arcades, however, only took place in these cases in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when trading in public spaces gave way to independent shops on ground floors.Footnote 45 A certain liberalization of regulations must have occurred, which over centuries had secured continuous passage through arcade passageways as a critical element of the transportation systems. Such regulations are not preserved in Silesia, but are known from Swiss and Italian sources. For example, in Bern, all items hampering passage under the arcades had to be removed (1615), and the breadth of the trading benches was also regulated (1558).Footnote 46

Figure 9. Legnica, a fragment of a cadastral plan showing the city centre before the demolitions. In the northern part of the market square, frontage lots block the street entrances to the square (marked with arrows). Plan developed by R. Eysymontt and M. Siehankiewicz on the basis of plans from 1863: R. Eysymontt and M. Goliński (eds.), Atlas historyczny miast polskich, vol. IV (9) (Wrocław, 2009), map 1.

Figure 10. Bricked-up arcades in Chełmsko Śląskie, Rynek 29, 30 (top) and Mirsk, Plac Wolności 15 (bottom).

The accessibility and functionality of existing arcades were maintained even when the arcades themselves were gradually eliminated. In Kamienna Góra, the frontage of a prestigious tenement house at 6 Wolności Square was drawn back so that the arcade passages in front of the neighbouring houses could remain functional. It might also be an example of an attempt to break the regulations that imposed the construction of arcaded passages in front of houses, as they prevented noble families from displaying the impressive frontages of their palaces, as in Bologna.Footnote 47

These observations lead us to consider the possibility of reconstructing arcades that were neither depicted in historical or iconographic sources nor confirmed through archaeological or architectural studies. This would apply, for instance, to Bystrzyca Kłodzka, Duszniki-Zdrój, Dzierżoniów, Głuchołazy, Kożuchów, Lubań, Lwówek, Ząbkowice Śląskie and Ziębice. In these cases, arcades would have had to have been eliminated before the mid-eighteenth century, as they are absent from town views dating back to this time. Such an action would have included incorporating the former arcade zone into houses, which itself would have required the consent of the municipal authorities.

Confirming the existence of arcades in towns where they have been demolished and where the front line was set back by the width of the arcaded space is much more challenging. If such arcades did not have cellars, archaeological excavations can provide evidence of their existence. An example of arcades that were removed from a plot can be found in the sixteenth-century town of Grodków. A decree issued in 1549 by Wrocław’s Bishop Balthasar served as a kind of reprimand for faulty repairs of fire damage; contrary to previous orders, the arcades were not completely demolished.Footnote 48 This document highlights two fundamental problems to urban order: houses with arcades protruding into the streets and inflammable building materials. Although arcades were not prohibited, they did have to be built within plot boundaries. Withdrawing the frontages may have resulted in cellars remaining under streets or squares. The relationship between the cellars and arcades warrants further study.

Architectural studies conducted in Świdnica have led to the hypothesis that the front houses at 1, 22, 33, 35 and 36 Rynek, built in the mid-fourteenth century, were not structurally attached to the arcades but merely adjoined them.Footnote 49 No other Silesian town has similar structures, but they do occur in bastides such as Cologne, Monflanquin and Villeréal (Figure 11). However, the French houses were not as precisely dated as the ones from Świdnica. The separation of the arcade from the house was not always simply structural; it is also an indication of a different date of construction for that part of the house. The sheltered space in front of the house and the floors above it may have had commercial or craft-related functions,Footnote 50 and thus were also functionally separated. D. Friedman noted that the nineteenth-century cadastral plans of the bastides frequently show arcaded spaces separated from houses and with separate addresses and house numbers.Footnote 51 Independent access to the upper floors, preserved in some French towns, further attests to the autonomous status of the front floors. The first floor can be reached through steep stairs from the arcade, as in Villeréal and Molieres, or through entrances designed in the pillars, as in Monpazier or Monflanquin (Figure 12). Friedman also noted that in Libourne, the arcade and house floors were at different levels.Footnote 52 Another interesting piece of evidence comes from Trie sur Baïse, a town founded in 1321. When the municipal authorities wanted to demolish one of the arcades in the main square in 1868, the property owner demanded that action should be taken to ensure that the front wall of his house was not damaged.Footnote 53

Figure 11. Villeréal, New Aquitaine, corner of Place de la Halle and Rue Saint-Roch, an example of structural and functional independence of the arcade and the room above.

Figure 12. Villeréal, New Aquitaine, corner of Place de la Halle and Rue Saint-Roch, stairs leading to the room above the arcade (top). Monpazier, New Aquitaine, 11 Place des Cornières, entrance located in the pillar of the arcade leading to the room above (bottom).

According to L. Giacomini’s study of the arcade system in subalpine areas, vertical communication between floors was based on simple ladders placed between arcade supports.Footnote 54 This confirms the independence of the different sections of the building beneath and above the arcades.

As noted already, it is impossible to determine how the arcade space and floor functioned in Silesian towns, but the arrangements described earlier seem plausible. Another element that constituted a functional complex within the commercial area of the arcade were the cellars. F. Ceccarelli observed specific walls separating arcaded spaces from the streets in Bologna,Footnote 55 which were constructed in the first half of the fourteenth century. The cellars were built when wooden arcades were replaced with brick ones. The walls extended deep down and aligned with the outer cellar walls. This solution compensated for the loss of space due to the need to build arcades within plot boundaries, for private property extended both above and below the arcade.

The best-known and most recognized example of a medieval cellar associated with an arcade is the 17 Kramgasse in Bern. As in other Zähringer centres, citizens were allowed to set up trading stalls in front of their houses. In the fourteenth century, they received a codified privilege to erect ‘arches’ and superstructures over them. In Kramgasse, two underground spaces were discovered. The one under the house was larger and situated at a considerable depth.Footnote 56 The second one, under the arcade, was smaller, vaulted and at a shallower depth. These differences led scholars to argue that the cellars had been constructed at different times. Friedman believed that cellars had a storage function.Footnote 57 Originally, the cellars under the houses in Bern only reached the inner walls of the arcade.Footnote 58 Under the arcade floor were the so-called Kellerhals, the entrances from the arcade to the cellar behind it. Subsequently, the so-called Vorkellern were constructed under the arcades. Today, the cellars are connected through doors and stairs and are accessible from the outside only via arcades.

The Silesian examples do not indicate a clear connection between the location of the cellar and the arcades. This may be due to the different times at which particular elements were constructed, the existence of older structures or owner-specific requirements. Some underground floors are located within the arcade outline, and others are elongated, extending from the front or rear arcade wall towards the rear of the plot perpendicularly to the street (Figure 13). Cellars situated parallel to building lines under the arcades (e.g. in Jelenia Góra, Jawor and Świdnica) are presently accessible from house interiors through a system of underground rooms and ramps. Initially, they were accessed through descents in the arcade space. Similar solutions can be found in towns on the River Inn, such as Mühldorf am Inn, Neuötting and Wasserburg am Inn. Archival photographs show such stairs in Jelenia Góra (Figure 14). A more convenient descent could be designed when the arcade level was raised such that a suitable angle for a staircase was created with the Kellerhals perpendicular to the house façade (Figure 15). Such cellar descents occurred in Jelenia Góra and still exist in Landshut and Lindau (both in Germany). The most convenient cellar access was found in arcades that were elevated on terraces, where the entrances were located at the front.Footnote 59 This design can be seen in Bolków, is mentioned in archival sources for Kłodzko and was discovered through historical and archaeological-architectural investigations in Świdnica (Figure 16). Elevated arcades are also typical of Swiss towns (Bern, Erlach, Estavayer-le-Lac, Freiburg im Üechtland), and an impressive example can be found in Brisighella in the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna (Figure 17). Similar elevated arcades also occur in towns like Chester in England and Bielsko-Biała and Przemyśl in Poland.

Figure 13. Jawor, plan showing the layout of the cellars under the arcaded houses standing at the market square (marked with dark grey).

Figure 14. Jelenia Góra, pre-1945 photograph showing basement entrances located in the front areas of the arcades. Herder-Institute archive, sig. 233697.

Figure 15. Bern, Kramgasse, basement entrances located in the front areas of the arcades.

Figure 16. Kłodzko, Czeska Street, the high arcades that no longer exist, source: https://polona.pl.

Figure 17. Brisighella, the high arcades at Piazza Guglielmo.

Thus, the architectural town landscape in Silesia reflects a series of stages in the creation of arcades and associated cellars, demonstrating that a variety of solutions was applied. Occasionally, cellars were constructed only under a house, possibly predating the arcades. Other times, additional underground floors under the arcades were built, or a single cellar was situated under both parts of a house. It is also likely that older cellars were not chronologically connected to later arcaded houses. The current lack of access from the arcades to the cellars in most towns where arcaded buildings have been preserved may be associated with abandoning the tradition of trading in open spaces in front of houses and the inclusion of underground floors in the cellar system under the house.

Can cellar arrangements indicate the former presence of arcades in towns where they no longer exist? In cases where arcades were incorporated into houses, small frontal cellars are likely to indicate the remains of underground floors under arcaded spaces. Drawing back the building line might be expected to have resulted in underground floors in front of buildings, hidden under streets and squares. However, no such cases have been identified in Silesia. Cellars slightly crossing the front building line were recorded in Świdnica, mainly in the streets leading to the market square. This may confirm information from fourteenth-century written sources regarding the width regulation of the town’s streets. However, these regulations did not necessarily result in the complete elimination of arcades, and regulating the width of streets without arcaded houses would have had the same result. Silesian towns failed to build cellars beneath streets or squares that extended beyond the modern building line. Therefore, it can be assumed that the oldest cellars did not reach the arcades but were located under the ‘proper’ house. Access to these cellars might have been from the front or the arcaded space via the Kellerhals. The bricked-up passages in the cellar walls in Świdnica houses seem to be the remains of such descents. This resembles the dynamics of constructing cellars in Bern, as discussed above. It is also possible that, before the elimination of the arcades in some of the towns discussed, the arcaded spaces did not have cellars; instead, the merchants used the upper floors or attics, as in the case of the bastides. It is also important to consider the limited state of Silesian urban archaeological and architectural research; therefore, the interpretations presented here should be the subject of future research.

Public or private space?

The issues discussed above lead us to the final question: what role did land ownership play in the bricking up of arcades? Did this occur when the arcades were located within the burgher’s plot and were they demolished when they extended into public spaces? There are no European medieval centres where a layout with arcaded passages was undoubtedly planned and immediately implemented, meaning that no model solution exists. If we consider the bastides Villefranche-de-Rouergue, where the arcades were introduced secondarily according to written sources, and Créon, with its pre-designed front arcades, the answer is still unclear. In Villefranche-de-Rouergue, the arcades are significantly extended towards the square and meet at its corners, forming gateways. The arcades match the widths of the streets running into the market square and are currently accessible for car traffic (Figure 18). The situation is similar in Créon, where the arcade sections were most likely moved back after their construction to widen the entrances to the main square. This may have happened in the nineteenth century, when the arcades in the south-western frontage were removed. Thus, it was not considered appropriate to arrange the building blocks in such a way that the main square entrances were blocked.

Figure 18. Villefranche-de-Rouergue, the south-west corner of Place Notre-Dame with its adjacent arcades.

We could also do the opposite and examine Silesian towns where arcaded houses never emerged, such as the well-studied capital city of Wrocław (a similar arrangement probably existed in Brzeg). In both places, the streets opening into the market square were not blocked by protruding frontages, which would have occurred if arcades had ever been present. However, even in Wrocław, intrusion into public zones could not be avoided, which suggests that secondary modifications of urban layouts sometimes had to be accepted. In the second half of the thirteenth century, the rapidly rising level of the main square required the construction of stairs at house frontages to provide access to what had been the basements.Footnote 60 After the square level was stabilized in the mid-fourteenth century, the stairs were removed and the former basements became upper cellar levels.Footnote 61 This indicates that public spaces could occasionally be encroached upon and later abandoned.

The Silesian, French, Italian and Swiss examples demonstrate that arcaded houses were not planned as an integral part of a newly arranged urban layout. In his study of arcade buildings in Piedmont, Giacomini argued that none of these early urban designs featured a system of porches and that the process of regulating arcades concluded at the end of the fourteenth century.Footnote 62 For instance, the introduction of arcades into public spaces was confirmed in Cuorgné, where maintenance costs were split between the municipality and private property owners. Furthermore, the front sections of medieval buildings, consisting of a cellar, arcade and the room above them, were built on independent foundations. Durable stone and brick porch systems existed in this area as late as the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.Footnote 63

In Padua, the decision to build or remove arcades in public spaces was most likely made on a case-by-case basis. In 1421, a certain Leonardo obtained permission to occupy a piece of public land in Piazza della Paglia (now Piazza Garibaldi) to build a porch in front of his house.Footnote 64 That same year, Contenovello di Mezzoconte was allowed to enclose the ‘porticulum’ adjacent to his cellar, facing Borgo di Ser Lolo (now via dei Livello), with a wall.Footnote 65 Permission was granted on the premise that the porch was his private property. This does not alter the fact that, in 1492, the municipality decreed that house owners were required to pave all arcades.

Arcades in public spaces – or at least the ability of municipal authorities to influence their use – is evidenced by documented cases in which decisions were made regarding who could trade there. One such example occurred in Biała, where a dispute arose over whether Jews should be allowed to trade in arcaded spaces.Footnote 66 Another case was from Münster, where arcade owners resisted the municipality’s efforts to relocate the retail merchants who rented space from them.Footnote 67 This dispute lasted for centuries and eventually raised the question of the ownership of the arcade space. By the late eighteenth century, the council rejected the house owners’ demands, declaring that while the pillars and walls of the arcade belonged to the house, the arcade space itself did not. The council argued that the traditional right to pass through open arcade spaces belonged to the public. Although the origins of the arcades in Münster are unclear, it is likely that the owners of arcaded houses were permitted to extend them into the public domain. Thus, even the townspeople may not have known the true origins of the arcades.

In the European context, an extraordinary situation occurred in Bologna, which boasts the longest documented tradition of arcade construction, spanning approximately a thousand years. Without delving into the complex processes that led to the unprecedented popularity of porticoes there, it can be said that after a period of chaotic development in the oldest part of the town, a process of spatial reorganization began in the thirteenth century. Aligning the building lines was an essential element of this process. Most likely, experiences from the newer part of the town, stretching outside the sixth-century selenite walls, were used. In these areas, arcades were mandated to be situated within private plots. Bocchi and Smurra argued that the process was a transition ‘from the private use of public land to the public use of private land’ – arcades became obligatory, although they were located on private plots.Footnote 68 The regulations were applied to entire street frontages. The resolution issued in 1211 focused on the regulation of streets created after filling the moats near the selenite walls. According to this resolution, the streets were to be 10 feet wide and built with arcades, but without them intruding into the street area. The Bologna Charter, issued in 1288, stated that all those who owned houses or plots without arcades where they were customarily present were to build them on the street frontage. Moreover, the owners were responsible for their maintenance.Footnote 69

Based on the identified situation in Silesian towns, it seems that the withdrawal of the frontage lines by the width of the arcades, that is to within the original plot boundaries, was possible at an early stage, when the buildings had not yet been stabilized and constructed with permanent materials, and before the arcade cellars were established. Later, the demolition of the arcades would have been more complicated and would likely have been met with strong resistance from residents. Therefore, later elimination of the arcades was possible, mainly by bricking them up, which also had the advantage of extending the original plot. As other European examples have demonstrated, encroaching upon public space was the most common strategy.

Summary

Arcades significantly transformed the spatial regularity of Silesian towns. Surrounding the main squares, they introduced a buffer zone between the public and private zones, enhancing the functional layout of houses and squares and becoming an essential element of the urban landscape. The arcades occupied most of the width of the street in the corners of the square, forming gateways that led into the most important urban space and separating vehicle and pedestrian traffic. The main square entrances were always designed so that the arcades did not meet, and the entrances to the square were not too narrow, distinguishing them from many French bastides. The seriousness of this issue in French towns is highlighted by the fact that arcades on corner houses were eliminated, by the practice of oblique undercutting and even the removal of arcades along entire frontages. Although spatial solutions similar to those in the Silesian examples may be found in arcaded bastides, Silesian towns matched most closely towns in the Czech Republic. České Budějovice and Jičín have a similar urban layout, at least in the main square areas.

In some Silesian towns, the main square arcades were coupled with arcaded passages stretching along major streets. Later, these structures were the first to be removed, probably because they narrowed the streets and impeded traffic. Consequently, they are difficult to trace in the towns’ current spatial and architectural structures. This widespread distribution of arcades outside the main squares also occurred in Italy (e.g. Bologna and Padua), Switzerland (e.g. Bern) and the Czech Republic (e.g. Trutnov). However, in the main square quarters, the frontage lines, cellar arrangements and bricked-up frontages of the buildings reveal the old layout of the arcaded squares. Careful observations, historical sources and visual sources suggest that arcades were present in most Silesian towns, although they may have appeared at various stages of development.

What was specific to Silesian towns, especially those in the mountainous Sudetes region, was that the craftsmen’s colonies were not located in the market. The colonies featured arcaded houses that provided convenient spaces for work. Notably, a waterfront arcade in a district remote from the centre was recorded in Nowa Ruda. River-facing arcaded houses also occur in Treviso and Schifflaube in Bern, but their origins are unknown.

Determining when arcades were introduced presents considerable challenges. Silesia’s oldest preserved arcaded houses date back to the sixteenth century. However, written sources unambiguously state that they already existed in the first half of the fourteenth century. Additionally, the lack of urban documentation from the thirteenth century obscures earlier details. As later documents consistently refer to arcades as existing structures, it is reasonable to assume that they were present in Silesia as early as the thirteenth century. The arguments discussed in this study allow us to believe that the arcades were not part of the original urban layout and were introduced subsequently, possibly shortly after the town’s foundation. This is consistent with most of the well-studied European centres, as arcades were often built in public spaces, not on the owner’s plot.

For this reason, Silesian municipal authorities quickly saw the need to regulate the spontaneous introduction of arcades. In the fourteenth century, arrangements were made to legitimize or remove this element from the town structure. It seems their elimination – by moving the building line back to the original plot boundary – was only feasible during the initial phase of urban development or in buildings constructed with perishable materials. Over time, the increasingly established development made any changes difficult, so the arcades had to be either kept or eliminated by bricking them up, thus removing their fundamental advantages of accessibility and openness.

The discussion of urban arcaded architecture in the Middle Ages and the early modern period presented in this article suggests that the situation in Silesia mirrors the chronology of transformation and dynamics observed in other, much better-studied European regions, where this architectural element is considered characteristic. It applies to French bastides in New Aquitaine and Occitania, as well as towns in Piedmont or Emilia-Romagna. Many areas geographically closer to Silesia that might have constituted a direct urban-planning inspiration have yet to be studied, such as the Czech or Bavarian towns (especially those on the Inn River). Thus, Silesia belongs to a large distribution zone of arcaded buildings, an element significant for architecture and urban planning. The examples above demonstrate the similarity of the applied solutions, although there is no convincing evidence of the shared origins of this phenomenon or inter-regional influences, which require further studies.

Funding statement

This article is a result of studies carried out as part of a project funded by the National Science Centre Poland, Research Project No. 2017/25/N/HS2/01161 titled Silesian arcade architecture in the European context (13th–18th c.).

Competing interests

The author declares none.