Introduction

Constitutions have sometimes been adopted with the intent of transforming the larger society, a phenomenon referred to as “transformative constitutionalism” (Hailbronner Reference Hailbronner2017). The South African Constitution, for example, is frequently described in terms of thoroughgoing transformation in dismantling the prior system of apartheid in favor of the equality of citizens across all spheres of life (Klare Reference Klare1998; Klug Reference Klug and Dann2020). The Indian project, moreover, has been described as “militant” insofar as it aspires to root out a deeply-entrenched caste system, as opposed to more “acquiescent” constitutional projects that assume society’s status quo (Jacobsohn Reference Jacobsohn2010, 213–270). Such transformative projects as these implicitly suggest and even depend upon the possibility that constitutions have some power to alter behavior of individuals and institutions in private spaces. How, then, might constitution-makers go about writing a constitution with the capacity to transform the polity across public and private spheres alike?

Prior research examines when classical political rights and even socioeconomic rights, plausible means for transformation, are likely to be included in constitutions (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2004; Dixon and Ginsburg Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2011; Dixon and Ginsburg Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2017; Holzinger, et al. Reference Holzinger, Haer, Bayer, Behr and Neupert-Wentz2019; Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022). However, existing scholarship ignores another kind of rights protection, one that is arguably an even more potent tool for constitutional transformation. This is the practice of applying rights “horizontally” so that they create obligations for private actors vis-à-vis other citizens’ rights. For example, the South African Constitutional Court relied on this mechanism in imposing a constitutional duty on a landlord to ensure that his tenant lived in conditions consonant with human dignity. This was not merely a matter of housing codes or statutory law, nor part of a specific list of citizens’ duties in the constitution. Rather, this was an extension of existing constitutional rights so that the landlord now shared the obligation to uphold another’s constitutional right to dignity in housing.Footnote 1 While a number of scholars have examined horizontality in legal literatures (Woolman and Davis Reference Woolman and Davis1996; Gardbaum Reference Gardbaum2003; Preuss Reference Preuss, Sajo and Uitz2005; Clapham Reference Clapham2006; Kumm Reference Kumm2006; Chirwa Reference Chirwa2008; Liebenberg Reference Liebenberg and Langford2013; Nolan Reference Nolan2014; Frantziou Reference Frantziou2015; Hailbronner Reference Hailbronner2017; Bhatia Reference Bhatia2023), precious little on this practice exists in political science (see Mathews Reference Mathews2018 for one example). No prior scholarship considers in a large-n study why, when, and how constitution-makers would adopt horizontality provisions that allow for the extension of constitutional obligations to private actors. Existing studies do not distinguish between rights that simply include additional protections and those that impose obligations on more members of society, including private actors, to protect those rights. Horizontality is also distinct from the kinds of “common legal duties” or even “aspirational duties” that most frequently create obligations of individuals vis-à-vis the state or society at large (Versteeg and Alton Reference Versteeg and Alton2024, 5). We ask, under what conditions do constitution-makers adopt horizontality provisions with the intention that constitutional norms transcend or “radiate”Footnote 2 across spheres of the polity in this way?

Building on recent scholarship showing the importance of studying how constitutions are drafted (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt, LeVan and Maboudi2015, Reference Eisenstadt, LeVan and Maboudi2017, Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019; Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022), we focus on the process of constitution-making as a critical factor in introducing a constitutional basis for horizontal application. We contend that horizontality provisions are more likely when there is a meeting of the minds, or in other words, when mutual commitments from a broad cross-section of society are expressed at the negotiating table.Footnote 3 Following Eisenstadt and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019), we refer to such a process as “inclusive,” meaning that political parties, interest groups, civil society organizations, and other social and political groups are all included in (or not excluded from) the constitution-making process (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019). The inclusivity of the process is distinct from the level of popular participation, which is the extent to which the general public is involved, or the simple aggregation of individual participation (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019; Maboudi Reference Maboudi2020). In contrast with direct popular participation, inclusive processes ensure that a wide range of diverse interests are represented and given powerful expression in the constitution-making process. We also argue that such a meeting of the minds is more probable when the environment is less conflictual; in other words, mutual commitments will be harder to make as violent societal conflict increases in intensity.

To be clear, we suggest that such a process is more likely to provide political foundation in the constitutional text for the practice of horizontality. While the promise of doctrinal implementation and legal development arguably underlies constitution-makers’ choice to adopt these provisions, the ultimate doctrinal form of horizontality is typically left to the courts and subsequent political-legal developments. Although we discuss such pathways of enforcement below, the doctrinal particularities are not essential to our core argument that the adoption of this form of transformative constitutionalism is more likely to result from an inclusive process. In understanding the constitution as, in some way, obligating state and private actors alike, this practice presupposes the juridical unity of the entire legal order. In short, this is a major shift in the constitutional terrain and, hence, will require a meeting of the minds.

Before explaining our core argument connecting an inclusive process to the adoption of this constitutional practice, we first highlight the singular nature of horizontality as a type of rights protection and an instrument of transformation. In doing so, we provide illustrative provisions and case examples of effectual horizontality enforcement against private parties and begin to establish a link between those parties included in the constitution-making process and those acquiring new obligations with this development. Next, we explain our theoretical approach to understanding the adoption of horizontality, illustrating our argument with the paradigmatic case of South Africa and the less-explored example of Zimbabwe. The latter allows us to isolate and demonstrate the explanatory power of an inclusive process, as opposed to a participatory one, and serves to clarify that inclusivity, our independent variable, does not necessarily equate with equality in representation or power. We then test our theory on cross-national data concerning the adoption of horizontality over time, discuss our findings, and make suggestions for future research.

The (transformative) potential of horizontality

Horizontality provisions in constitutions mark a clear departure from conventional narratives and comprise a transformative instrument in the fullest sense (Hailbronner Reference Hailbronner2017; Bambrick Reference Bambrick2020). The essential and obvious difference between traditional rights protections and the shift to hold private actors accountable for rights is the subject – whom these rights constrain. On conventional accounts of constitutionalism, rights create obligations for the government. Thus, Dixon and Ginsburg’s insurance model (2011, 2017) and Hirschl’s hegemonic preservation thesis (2004) offer compelling explanations for the choices of political elites in power at the time of the constitution’s adoption, who understand that they are not likely to retain power indefinitely. Rights protections provide for their future security. Contrast this with the choice to apply constitutional norms to the private sphere, a move which, unlike traditional rights, protects not against government, but private actors, and promises to empower some players, including judges who often apply those duties (Stone Sweet Reference Stone Sweet2007; Mathews Reference Mathews2018). While this practice will result in more extensive rights protections for some in private spaces, the choice necessarily results in more extensive obligations for others.

To support our argument that horizontality provisions in constitutions can indeed produce such obligations, we highlight cases applying horizontality provisions in South Africa and Kenya. While a full examination of the jurisprudence of these countries is beyond the scope of this paper, these cases demonstrate the political and legal efficacy of horizontality. In other words, they show that horizontality provisions “have teeth.” These countries’ cases are ideal for our purposes because they have been discussed by legal scholars, we have access to the judgements, and they illustrate the diversity of the specific wording of constitutional provisions. Kenya’s provision is short but broad: “The Bill of Rights applies to all law and binds all State organs and all persons” (Art. 20(1)). South Africa’s provision is also broad, but longer:

-

2. A provision of the Bill of Rights binds a natural or a juristic person if, and to the extent that, it is applicable, taking into account the nature of the right and the nature of any duty imposed by the right.

-

3. When applying a provision of the Bill of Rights to a natural or juristic person in terms of subsection (2), a court-

-

a. in order to give effect to a right in the Bill, must apply, or if necessary develop, the common law to the extent that legislation does not give effect to that right; and

-

b. may develop rules of the common law to limit the right, provided that the limitation is in accordance with section 36(1).

-

-

4. A juristic person is entitled to the rights in the Bill of Rights to the extent required by the nature of the rights and the nature of that juristic person.

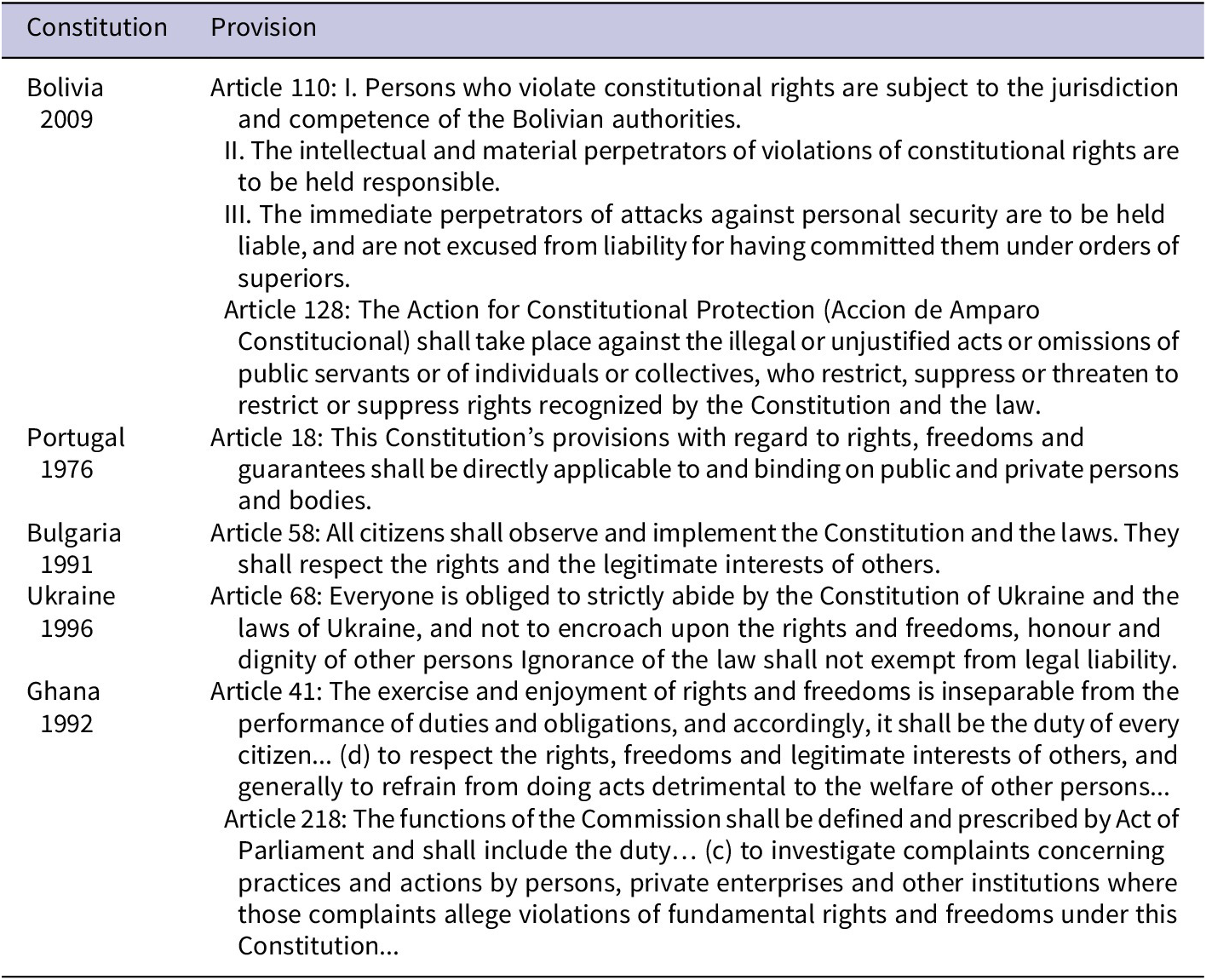

Table 1, below, displays additional examples of constitutional horizontality provisions that reflect their diversity in wording and regional origin.

Table 1. Illustrative Examples of Provisions for Horizontality

Such provisions all establish broad rights and, frequently, ground extensive case law to define and enforce them. This feature distinguishes horizontality from common enumerated duties found in 70% of constitutions (Versteeg and Alton Reference Versteeg and Alton2024). Such provisions list specific obligations, narrowing the number of cases to which they could apply: duties to “‘defend the country’ (found in 57% of all constitutions today), ‘respect the constitution’ (40%), ‘respect the laws/legitimate authorities’ (40%), ‘pay taxes’ (38%), and ‘protect the environment’ (37%)” (Versteeg and Alton Reference Versteeg and Alton2024, 6). What Versteeg and Alton term “aspirational duties” occasionally include enumerated duties to fellow citizens but are very rare as a general category (Versteeg and Alton Reference Versteeg and Alton2024, 6). Versteeg and Alton explicitly distinguish their focus from our own dependent variable, namely, more general textual provisions that allow constitutional rights to be applied to protect individuals from each other (Versteeg and Alton Reference Versteeg and Alton2024, 3 fn. 9). Our analysis of the inclusion of horizontality provisions and Versteeg and Alton’s “common duties” found that they are only weakly correlated (Pearson rho <1). Horizontality is indeed unique.

Before discussing the case law, it is worth noting a doctrinal distinction concerning horizontal application that, although not an essential difference for the purposes of our argument, is important in understanding the different legal mechanisms that may grow out of horizontality provisions. The major doctrinal choice is between direct and indirect horizontality. Under the direct approach, constitutional rights are a direct source of obligations for private actors, meaning that the constitution is the unmediated source of duties, and no additional law must be enacted for the provision to have legal force. The details of these duties are typically drawn through balancing exercises and will be different from those of the state. While not the most common doctrinal implementation of horizontality, it has been employed in countries as diverse as South Africa and Ireland. The indirect form of horizontality is varied, but the defining feature is that the obligations of private actors are somehow mediated by government action, such as enacting legislation, a legislative “duty to protect” against private harms, or a judicial duty to interpret and develop private law (such as the common law) in alignment with the constitution. Many scholars are skeptical that one of these forms is stronger than the other, since in both cases constitution-makers are effectively committing the country to measure private behavior against a constitutional standard (Kumm and Ferreres Reference Kumm, Comella, Sajo and Uitz2005). With direct horizontality, private actors can plead a cause of action solely based on the constitution. With indirect horizontality, the constitutional principles control the content and interpretation of all areas of the law, allowing the constitution to shape existing law that regulates private spaces. In either approach, however, the constitution is the standard according to which private behavior is constrained.

In our study of case law, we begin with South Africa, the paradigmatic case for horizontality. In Daniels v. Scribante and Another (2017), mentioned above, the Constitutional Court of South Africa drew upon the horizontality provision (Section 8(2)) to impose an obligation upon a property manager and owner under the constitutional right in section 25(6).Footnote 4 This right, located in a broader provision on property, guarantees secure tenure of land and, the Court elaborates further, dignity in living conditions. As a result, these private actors had an obligation not to obstruct Ms. Daniels’s efforts to make her basically uninhabitable dwelling livable. Her improvements included such basic measures as leveling the floor, installing a water supply, and adding a ceiling. After the Constitution’s adoption, Parliament enacted crucial legislation (the Extension of Security of Tenure Act or ESTA (1997)) to further enforce section 25(6) rights. Nevertheless, the Court states specifically that the source of the private actors’ obligations here is ultimately the Constitution itself (para. 38).Footnote 5 This particular case is also notable as the first instance the Court acknowledged that horizontality may in fact give rise to positive obligations – that is, private actors may have obligations requiring positive action in the course of realizing others’ rights, especially socioeconomic rights.

Horizontality was also employed against individual landowners in King v. De Jager (2021), prohibiting the enforcement of a will that allowed only male descendants to inherit the testator’s farms for three generations. Three separate opinions drew on constitutional and statutory protections against unfair discrimination. One line of reasoning articulated by Justice Victor emphasized the role of direct horizontality in ensuring that the existing legislation (the Equality Act) does indeed protect the right in question. She speaks of the need to realize “substantive equality through the lens of transformative constitutionalism.” Similarly, Justice Mhlantla argued that common law rules, including those governing the enforcement of private testamentary provisions, had to be developed in line with the Constitution and constitutional rights. The Constitutional Court has also built upon the horizontality provision in cases concerning the right to a basic education, under Section 29. These cases include Juma Musjid (2011) when the Court decided that a private trust, providing the land for a primary school, had a constitutional obligation “not to impair the learners’ right to a basic education” through arbitrary eviction. Moreover, in Pridwin Preparatory School (2020), the Court decided that a private school had a constitutional duty to provide a basic education, specifically, that the school could not dismiss students without giving due weight to the children’s right to an education, as through a hearing.

In Kenya, the horizontality provision has been cited in the High Court’s case law to prohibit private member clubs from discriminating against women (Mambo v. Limuru Country Club, 2013). The country club directors declared the golf committee to be a “male only affair” (para. 8). The court recognized that it must not micromanage the internal affairs of private member clubs, but that their private nature “does not absolve these entities from the constitutional burden of adherence to constitutional values and principles” (para. 113). This ruling opened the door to numerous other suits against private clubs. In addition, in a case between two private sugar milling companies, judges on the High Court rejected the idea that the existence of an alternative remedy in private law is a basis for defeating the horizontal application of a constitutional right in battles concerning control over sugar production (Busia Sugar Industry v. Agricultural Food Authority, 2024). Lower courts have also employed horizontality to restrict a hospital from firing an employee who refused to attend a budget meeting on her day of worship, as the Constitution obligates private entities to respect individuals’ rights to exercise their religion (Ojung’a v. Healthlink, 2023). Justice Manani at the Employment and Labour Relations Court sitting at Nairobi reasoned that, “There is no doubt that the Respondent’s budget making process was of critical importance to it. It is also clear to me that the Claimant’s freedom of religion was of equal significance to her. The Constitution obligated the Respondent to respect and protect this right” (Ojung’a, para. 50).Footnote 6

In light of these examples of the efficacy of horizontality in practice, the following section, describing our theory, will elaborate the range of possible interests and goals behind constitution-makers’ choice to include horizontality provisions in constitutional texts, including as they relate to transformative aspirations. For example, the judgements of the South African Constitutional Court demonstrate clear motivation for developing horizontality to combat South Africa’s history of apartheid. And indeed, these were exactly the goals the constitutional drafters intended when they chose to include horizontality, as explained in the next section. Ultimately, the goal of the new transformative constitution implicated a broad and diverse cross-section of society beyond the state, from landlords and property owners, to private schools, and even individuals in their last will and testaments. Therefore, in addition to considering the incentives and role of political elites in constitution-making, as past scholarship does, we have strong reason to consider the incentives and participation of civil society groups and other private actors in studying these horizontality provisions. The imposition of such new obligations is in contrast to the prevailing notion of a duty-free liberal citizenship lacking any sense of responsibility for the welfare of the community (Marshall and Bottomore Reference Marshall and Bottomore1992; Joppke Reference Joppke and Baubock2019).

Theory: horizontality from a meeting of the minds

The previous section began to demonstrate the potential of horizontality and why constitution-makers might be motivated to lay a foundation for this practice in the constitutional text. We now turn more directly to our research question: What kinds of constitution-making processes are likely to give rise to horizontality provisions?

We hypothesize that this practice is more likely to be adopted when there is greater buy-in from across the polity in the constitution-making process. This means we expect to see horizontality provisions applying constitutional rights obligations to private actors when there is more inclusive participation in the process, and when representatives articulating diverse interests from across groups stand in support. This is due to the nature of this constitutional development: while it certainly extends rights protections, it simultaneously imposes obligations on new (read: private) actors for the first time. This kind of arrangement, we maintain, would most likely garner support only when voices representing diverse interests from across the polity offer assent, including political elites, who will always be involved in constitution-making (Murray Reference Murray and Negretto2020; Negretto Reference Negretto and Negretto2020), and private actors such as interest groups. Political elites may be particularly motivated to broaden buy-in from different corners of the private sphere in order to avoid later backlash at the ballot box in reaction to new constitutional duties. Moreover, this kind of buy-in will only be possible under circumstances of relative peace among the relevant parties. In our theory below, we begin by explaining why we believe group inclusion in constitution-making processes matters, focusing on its crucial role in the articulation of interests and in negotiation. We then identify the interests of key actors in society, first recognizing political elite interests and explaining why we believe these factors are not alone enough to explain horizontality. Next, we detail the broader interests of the polity’s private sectors and support our claim that mutual commitment from these actors, and a low-conflict environment, is crucial for constitution-makers to reconceptualize rights and duties in the manner that horizontal application proposes to do.

As noted above, in an inclusive process, political parties, interest groups, civil society organizations, and other social and political groups are allowed to be part of the constitution-making process (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019). Eisenstadt and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) draw on the political theory literature concerning deliberation to support the importance of inclusive constitution-making processes for democratic outcomes. They note that public interests collide with private ones in most ordinary decision-making settings, and public participation, or sheer numbers, does not ensure that ideas will perfectly aggregate into a constitution representing the median viewpoint. According to their argument, the powerful articulation of ideas at the earliest stages of constitution-making is key for increasing levels of democracy, and the breadth of inclusion of expert professionals advocating for these ideas is essential for this articulation to occur (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019). The authors cite the high-profile failures of participatory drafting processes in Iceland (2010), Egypt (2012), and Chile (2016) to produce stable constitutions despite consultation with the public through focus groups, social media, and workshops. These three constitution-making processes had low inclusion, meaning they excluded key groups from the room (self- or incumbent-led exclusion). By contrast, in highly inclusive processes with low public participation, such as in Tunisia (2014) and Colombia (1991), credible interest groups formally advocate for a wide array of societal positions. Such processes are more likely to generate improvements in democracy. Eisenstadt and Maboudi argue that the powerful articulation of interests at the earliest stage in the constitution-making process achieves the public support needed for passage and bolstering levels of democracy. We argue that such powerful articulation of interests by expert professionals, referred to as “deep” group inclusion (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019, 2142), is a significant factor in the trend to introduce private actors’ duties to constitutional rights through horizontality provisions. The inevitable diversity of interests must be channeled in the negotiation process for such a shift in the constitutional order to occur. To explain why such channeling is so important, we must identify the interests at stake. We do so next.

We define political elites as actors that enjoy influence and exercise power in political and legal processes, particularly those who seek election and hold political office. This may often, but need not by definition, refer to leaders of political parties. Why, then, would political elites agree to extend constitutional duties into private spaces? In a word, political elites, as a class, simply do not have that much to lose from doing so. Indeed, including horizontality provisions may constitute yet another mechanism through which to achieve public projects or gain the approval of international actors and NGOs. By definition, it is private actors that are facing greater constraints with this practice. Now of course, these groups are likely to overlap in certain cases. Considering the example of land reform in South Africa, for example, some political elites may well own extensive property as well. The point still stands, however, that the group to be constrained by the horizontal application of rights is not identical with the political elite class.

Political elites may not have all that much to gain from this practice, or at least they may not gain anything that they could not also achieve by other means. But that does not mean they have nothing to gain, or that they would have no strategic reasons for supporting the extension of rights protections into private spaces. Dixon and Ginsburg (Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2017) break down the different ways elites stand to benefit from adopting traditional conceptions of rights, applied to state actors, in an insurance understanding. Specifically, political elites have some chance to maintain access to political power, gain personal protection, or achieve policy preferences. These same motivations may find analogs when political elites agree to adopt constitutional protections in private spaces. Political actors arguably gain greater power over the private sphere. For example, judges may gain power by employing the language of “constitutional rights” to further domains, as Jud Mathews demonstrates occurred in Germany (Mathews Reference Mathews2018; see also Stone Sweet Reference Stone Sweet2007 and Van der Walt Reference Van der Walt2014).Footnote 7 Or, conversely, legislatures may cite constitutional provisions applying rights horizontally to justify exercises of power in private spaces, even limiting courts’ ability to impose constraints on such power through the enforcement of traditional “first generation” rights. James Tsabora describes such a dynamic in the context of Zimbabwe (2016).

Somewhat different from Dixon and Ginsburg’s typology, horizontal application may also offer political elites a method by which to shift the focus or even the blame for certain societal ills onto private actors. For example, Ernest Caldwell describes how judges of China’s lower courts portrayed themselves as “providing justice for the citizens caught in the grasp of the private sector” (Caldwell Reference Caldwell2012, 91).Footnote 8 Moreover, international law scholars find a variation of this argument a plausible explanation for the application of human rights to nonstate actors, particularly armed opposition groups (Rodley Reference Rodley, Mahoney and Mahoney1993; Nair Reference Nair1998, 13–14). Finally, extending constitutional rights obligations to private actors may well be another method of achieving certain favored policy goals. For example, with an eye to the long history of private segregation in the United States, the Indian framers included antidiscrimination provisions implicating private actors in their 1950 Constitution, specifically in Article 15, Section 2 (Tripathi Reference Tripathi and Beer1988, 78–79).

That political elites have potential reasons to extend constitutional rights obligations into private spaces seems evident. Indeed, the reasons are not all that different from the prior literature on how these elites benefit from including traditional rights in constitutions (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2002, Reference Ginsburg2003; Hirschl Reference Hirschl2004; Moustafa and Ginsburg Reference Moustafa, Ginsburg, Ginsburg and Moustafa2008; Dixon and Ginsburg Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2011, Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2017; Negretto and Sánchez-Talanquer Reference Negretto and Sánchez-Talanquer2021). However, the presence of these elite interests alone is not likely to be enough to lead to the adoption of horizontality. Rather, given the way this practice, by definition, addresses actions in the private sphere, we argue it is most likely to result from the combined interests of a broad cross-section of the polity. This second half of our theory is, arguably, more crucial to the paper insofar as it ascertains those “other interests” missing from standard insurance theories of rights, namely the diverse interests that private actors and members of civil society would have for extending constitutional rights and duties into private spaces.

By private actors we mean the broader public, including groups in civil society. As already explained above, elites also appear in this category but do not exhaust it. The distinguishing factor for our purposes, is that the interests of those in this group are characterized not by anything primarily political, but by patterns and expectations articulated in private spaces. These interests of groups from the broader populace may overlap with elite interests related to policy, in a similar way that Dixon and Ginsburg (Reference Dixon and Ginsburg2011) describe “insurance swaps” in the adoption of socioeconomic rights.

In sum, a broader cross-section of the polity contributing to the conversation as found in inclusive processes (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) results in

-

1. More diversity of interests represented and rights demanded, perhaps oriented toward transformation, including interests and issues that arise primarily in the private sphere.

-

2. Powerful articulation of these interests and rights demanded by expert professionals.

-

3. More willingness to assume an expansion of duties given the ability to ascertain a mutual agreement from all groups at the negotiating table.

So what then are the kinds of interests we would expect private actors and groups from civil society to bring to an inclusive constitution-making process? And why would the presence of these interests, alongside elite interests, combine in such a way to make the adoption of horizontal application more likely? Any goal that involves private spaces, whether a broad policy goal or some narrower desire to shape private behavior, could potentially be served by the practice of horizontal application. For example, individuals committed to social democratic norms, whether for pragmatic or idealistic reasons, may well have an interest in seeking the cooperation of private actors, that is, in extending constitutional rights obligations to private actors. Mark Tushnet describes this theoretical connection between social welfare rights and horizontality (Tushnet Reference Tushnet2008). Indeed, much of what transpires in private spaces has the potential to impact socioeconomic rights, whether positively or negatively. Consider once again the case of South Africa, whose constitution-making process we turn to next. In the Constitution, the government is technically the primary guarantor of the right to access to adequate housing (section 26). Naturally, however, much housing is possessed by private actors. Hence, section 8(2) establishing horizontal application has been employed to gain the cooperation of private landlords and landowners in securing housing (see Daniel v. Scribante (2017)).

South Africa’s constitution-making process

Participants in the South African constitution-making process discussed horizontality explicitly as a tool for dismantling apartheid.Footnote 9 Interestingly, horizontal application was rejected in the initial Interim Constitution that resulted from the elite-driven negotiations when the National Party (historically, the Afrikaner ethnic nationalist party) was still in power (Du Plessis and Corder Reference Du Plessis and Corder1994, 112). However, the second stage of the constitution-making process, which was much more inclusive of groups and receptive to popular input, did ultimately result in explicit and strong provision for horizontal application in the Final Constitution (section 8(2)). With the express goal of ushering in a new constitutional dispensation, this latter stage of the process included a broader cross-section of societal interests, in addition to the same political elites and parties of the prior negotiations. Ultimately, the National Party (NP) elites that had first rejected horizontality when they enjoyed greater power, yielded in this more inclusive second stage, deciding their efforts were better served elsewhere, such as in securing strong property rights.Footnote 10

In tandem with a vast public participation program, civil society groups worked jointly with the Constitutional Assembly to create a forum in which different sectors from across society could give formal voice to their respective interests. The hearings for this National Sector Public Hearing Programme occurred in May and June of 1995, and offered a platform to 596 separate organizations from across civil society. Participating organizations represented interests spanning business, land rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, traditional authorities, and religious groups (Ebrahim Reference Ebrahim, Ginsburg and Bisarya2022, 139–140). Notably, many of these interests have strong potential to carry rights obligations under a practice of horizontality, as evinced in the cases discussed above concerning land rights, property, children’s education, and the like. Moreover, civil society organizations also conducted “effective advocacy and lobbying campaigns on various aspects of the Bill of Rights. For example, women’s organizations lobbied successfully for a right in the Bill of Rights against all forms of public or private violence (s 12(1)(c))” (Liebenberg Reference Liebenberg2000, 10–11).

In this history we see one example of how elite interests and the interests of a broader public both diverge and align in complex ways when horizontal application is under consideration. In particular, horizontality became viable with broader input in the constitution-making process and increased sway of the ANC. Moreover, the circumstances under which horizontal application was argued in the South African case suggest that horizontality was employed to serve goals that may be understood as unconventional relative to traditional accounts of constitutionalism. If elites benefit from traditional rights protections such as the right to property per the insurance model, horizontal application may disrupt some traditional conceptions by requiring that other rights, say to have access to housing or to secure tenure of land, be prioritized in certain cases. Hence, constitutional duties of private actors may emerge when a sizable proportion of the population seeks transformative change, particularly in the private sphere.

Zimbabwe’s constitution-making process

The process of adopting Zimbabwe’s 2013 Constitution is also illuminating, albeit for other reasons. Examining Zimbabwe’s process is useful, in part, because power imbalances among the parties persisted throughout the constitution-making process. Such imbalance notwithstanding, this process is still classified as “inclusive” (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) and meets the threshold requirement to be categorized as “nonconflictual” (Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022). The choice of Zimbabwe also allows us to further illustrate the importance of the level of inclusivity for the likelihood of adopting horizontality regardless of the level of participation because the aggregate level of participation is at the mean, and the first stage was inclusive but not participatory. In short, this case allows us to isolate our independent variable in particular ways. In the circumstances, diverse interests, and discourses of this different constitution-making process, we still find present the very conditions that we theorize will increase the likelihood of horizontal application in a constitution.

Diverse interests were included and given formal voice in Zimbabwe’s process. An alliance of diverse civil society organizations, the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), was united in their condemnation of the power abuses of Robert Mugabe, the leader of the long-dominant African nationalist party, Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), and presented meaningful electoral competition for the first time (Manyatera Reference Manyatera2014, 22 fn. 23). ZANU-PF signed the Global Political Agreement (GPA) with the MDC (Ncube and Okeke-Uzodike Reference Ncube and Okeke-Uzodkie2015, 129), a “marriage of convenience,” bringing the major political parties together in a transitional inclusive government and initiating the process of adopting a new constitution (Mokhawa Reference Mokhawa2013, 28). While ZANU-PF retained a practical hold on power, the GPA required the next constitution to be “owned and driven by the people” and “inclusive and democratic” (Article 6). Members of both ZANU-PF and the MDC chaired the Constitutional Parliamentary Committee (COPAC), charged with drawing up the new constitution. Members of civil society were actively involved in the process as well. COPAC held two “All-Stakeholders’ Conferences” at different stages of drafting, that included actors as diverse as parliamentarians, partisans, members of civil society, and special interests. COPAC also distributed tens of thousands of copies of the draft constitution for the public’s review (“COPAC Takes Draft” 2013). After a multi-year process, an overwhelming majority of Zimbabweans voted to adopt the new constitution (Manyatera Reference Manyatera2014, 4).

While this process was certainly tainted by a strong executive from the existing regime and somewhat insulated parties, the wide involvement of diverse civil society organizations made its mark, evinced in the patent differences between the prior constitution and the final draft of the 2013 Constitution. The final Constitution reveals clear departures from the earlier Lancaster House Constitution to speak to more needs of the broader population, with provisions addressing a diversity of rights and interests. Khulekani goes so far as to describe the Declaration of Rights as the “epitome of the constitutional revolution” in Zimbabwe and “largely grounding the Constitution’s transformative vision” (Moyo Reference Moyo and Moyo2019, 32). Moreover, the Constitution included several provisions for horizontality.Footnote 11 The MDC had offered substantial support for horizontal application in the run-up to the referendum. Its promotional materials characterized this development as specifically benefiting workers, empowering them to “sue the State and any private employers for violating any rights or failing to honour any obligations that they are required to observe under the Constitution” (Movement for Democratic Change 2012). In their own analysis of the draft constitution, the organization Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights identified horizontal application as a positive change for the country (Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights 2013).

What distinguishes horizontality, and what at least some participants in these constitution-making processes recognized, is its scope and its ability to reach further, even into obscure corners of society, than traditional models of constitutionalism. It may well involve the application of old principles, say of equality, but to new and sometimes mundane spaces. Indeed, horizontality is ambitious, and potentially transformative, for the very reason that it makes constitutional principles more common. Presumably, it is in inclusive processes that more mundane concerns will be formally voiced. Traditional guarantees may even become secondary when access to more basic things are not also secure. And indeed, one would expect concerns of the latter category to come to the fore when a broader cross-section of the populace are represented in the constitution-making process. In short, private actors will have more private concerns, more related to daily life experiences than simply to politics (Zackin Reference Zackin2013). In this same vein, the kind of buy-in to constitutional principles and willingness to take on constitutional duties that horizontality requires is more likely in conditions of relative peace. Simply put, when there are lower levels of conflict, there is greater capacity for the collective action that would lead private actors to buy into constitutional principles, even as a source of new duties. In other words, we recognize that intense armed conflict would likely be a significant barrier to the “meeting of the minds” we describe.

It is worth noting that this prediction about horizontality resulting from situations that are more peaceful and conducive to collective action stands in contrast with findings of prior scholarship that minority rights tend to be adopted in higher numbers in post-conflictual settings, even when controlling for the inclusion of UN agencies and regional governance organizations (Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022). This contrast in the conditions giving rise to minority rights and those we predict give rise to horizontal application is not surprising in light of our argument about the fundamentally different logic of horizontal application. In examining horizontal application on its own terms in this article, we suggest the need for prevailing conditions conducive to collective action, deliberation, and meaningful assent for the very reason that private actors both stand to benefit and face additional possible constraints with this development. The more desperate compromises or urgent efforts to protect minorities that one might expect in post-conflictual settings simply do not describe the same intentionality and cooperation that we argue would lie behind efforts to transform society by extending constitutional rights obligations into private spaces.

Drawing upon this theoretical foundation, we develop the hypotheses below.

Hypothesis 1: As the level of inclusivity of the constitution-making process increases, the probability of adopting a horizontality provision increases.

Hypothesis 2: As the level of conflict intensity decreases, the probability of adopting a horizontality provision increases.

Research design

To empirically test these expectations, we employ both quantitative and qualitative data, drawing on several existing datasets and supplementing with our own coding. To examine the level of inclusion, and to control for the level of participation in our robustness tests, we employ data generously provided by Eisenstadt and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019). For our dependent variable, the level of horizontality, we draw on data from the Comparative Constitutions Project (CCP) (Elkins, et al. Reference Elkins2014) and the Oxford Constitutions of the World database (2020). In addition, to measure the level of conflict and the control variables, we use data generously provided by Fruhstorfer and Hudson (Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022). The authors gathered data from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO), the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (Coppedge, et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell and Altman2020), and from Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina2003).

To operationalize the phenomenon of interest, the adoption of horizontality provisions, we employ the CCP dummy variable Binding. (Elkins, et al. Reference Elkins2020) The CCP codebook puts the question for this variable in the following terms: “Are rights provisions binding on private parties as well as the state?” A few things about this phrasing bear out our interpretation of them as indeed horizontality provisions. First, the general nature of the variable, concerning “rights provisions,” suggests that this does not encompass enumerated duties or any specific content (as comprises the subject of Versteeg and Alton’s Reference Versteeg and Alton2024 study); rather, the provisions in this variable extend the reach of existing rights provisions, consistent with the definition of horizontal application. Moreover, this variable is limited to rights provisions, and does not encompass other kinds of duties to the state or society as a whole that would not qualify as horizontal application. Finally, the variable asks specifically whether rights provisions are binding on private parties, the very definition of horizontality. Thus, the illustrative provisions listed in Table 1 above meet this requirement, as they intend the application of constitutional rights to private actors, horizontality per se. Again, the presence of these provisions in a constitution does not necessarily entail that a doctrine of direct or indirect horizontality will follow, but only that the constitution-makers provided for some version of horizontal application, a kind of political foundation for this practice, in the constitutional text. This variable is coded 1 if rights provisions are binding on private actors, as our dependent variable.Footnote 12 The binding nature of the rights provision “must be explicitly stated, not just implied” (Elkins, et al. Reference Elkins2014, 105). If the provision states that “citizens must respect the rights and freedoms of other citizens,” it is coded as 1. This is the best indicator for the phenomenon we examine, the choice of constitution-makers to add an express provision assigning constitutional rights obligations to private actors.

Scholars have employed the Binding variable as one element of a larger index of minority rights, or those rights that protect groups experiencing “a pattern of disadvantage or inequality” (Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022, citing Healey Reference Healey2011, 16). However, this index does not distinguish horizontality from other protections that are traditionally aimed at state action, such as freedom of religion (Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022). As explained above, we argue that this distinction is key, warranting our separate analysis of horizontality provisions in the Binding variable. We employ the CCP data in our quantitative analysis. Moreover, because the content of past constitutions can influence the drafting of new constitutions (Fruhstorfer and Hudson Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022; Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2009), we consider whether horizontality provisions assigned constitutional rights obligations to private parties in a prior constitution. Again, we draw on the CCP historical data, tracking the Binding variable over time, to account for this potential influence, and supplement with our coding from the Oxford Constitutions of the World database (2020) of available constitutions for the presence of horizontality. We have data on whether or not horizontality was included in 139 constitutions (in 120 countries) adopted between 1974 and 2014. A total of thirty-eight of the constitutions we examine adopt horizontality and 101 did not. We list examples of such horizontality provisions in Table 1 above. We employ a dummy variable for whether the constitution includes a provision making the constitution binding on private individuals (1) or not (0).

Our main independent variable of interest, inclusivity, is the degree to which political parties, interest groups, civil society organizations, and other social and political groups are included in the constitution-making process (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019). Three separate variables measure the level of inclusivity at each stage of the process (origination, deliberation, and ratification) as either non-inclusive (0), mixed (1), or inclusive (2). In the first stage, origination, individuals actively and directly involved in writing the content are selected; in the second, deliberation, the constitution is drafted; and in the third stage, ratification, the constitution is ratified. To be categorized as inclusive in the first and second stages, the process would include representatives from all major groups at the table (again, not necessarily of equal power, but given seats). For the third stage to be considered inclusive, the constitution must be ratified by referendum or by a representative constituent assembly without any boycotts from a major political/social group.Footnote 13 Eisenstadt and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) cite the drafting of the Egyptian Constitution of 2012 as an example of a non-inclusive process, where the Muslim-Brotherhood dominated Constituent Assembly wrote the new constitution against accusations of excluding non-Islamists. The variable Inclusion-Aggregate is the sum of the levels of inclusivity at each stage, ranging from 0 (non-inclusive in all stages) to 6 (inclusive in all stages). To test Hypothesis 1, we employ this aggregate variable and the constitutive variables for the level of inclusivity, disaggregating the effect of the inclusion of major groups at each stage (Inclusion-First Stage, Inclusion Second-Stage, and Inclusion Third Stage). We were able to match Eisenstadt and Maboudi’s (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) data on inclusivity with our horizontality data concerning 127 constitutions.

Eisenstadt and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) make clear that inclusion, our main variable of interest, is distinct from participation. The latter is a measure of the extent to which the general public at the individual level are involved in each stage of the process, while inclusion measures the degree to which groups at the aggregate level are at the table. The key distinction lies in the method by which “the public will is translated into policy outcomes” (Maboudi Reference Maboudi2020, 51). Inclusion, which involves the formal advocacy by interest groups of societal positions, is akin to Dahl’s notion of pluralism, conceptualized as the array of groups beyond the electorate contributing resources and positions (Maboudi Reference Maboudi2020). Public participation is the aggregation of the preferences of the masses through more direct consultation, rather than through the voices of representatives. A process may involve both methods of translating the public will into policy outcomes, but not necessarily. Major political and social groups can be involved in the process while the general public is not. Thus, the process can be inclusive and not participatory (see Maboudi Reference Maboudi2020, 53, for the example of Portugal 1975–1976). The methods are not mutually exclusive, nor are they always paired together. In other words, the choice to obtain feedback from the general public does not necessarily cause the inclusion of major social groups, and vice versa. The two are measured on the same scale (non-inclusive/participatory, mixed, inclusive/participatory) and at the same time in each stage of the process (Eisenstadt and Maboudi Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019). Hallmarks of participation are direct election of members of the constituent assembly at the origination stage, public deliberation and involvement in writing the constitution in the deliberation stage, and ratification through referendum.

Table 2, below, displays the number of constitutions in our dataset that are coded at each level of inclusivity and participation at each stage of the process, origination, deliberation, and ratification.

Table 2. Levels of Inclusivity and Participation at Each Stage of the Process

In our dataset, most processes are not inclusive or participatory in the first stage, origination. Recall that this is when the constituent assembly is selected. This can be done through election or appointment. An inclusive process at the origination stage requires the inclusion of representatives from all major groups, whether elected or appointed, in the constituent assembly. As noted above, to be categorized as participatory, the members must be elected by the public (Maboudi Reference Maboudi2020). Zimbabwe is a good example of a case in our dataset in which the composition of the constitution-drafting body was inclusive, but not directly elected by the public. Greater variation is found in the second and third stages. We therefore analyze the effect of inclusion at each stage of the process, as well as in the aggregate, in our main models. We also conduct several robustness checks to explore the relationship between inclusion and participation, and their individual impacts on the adoption of horizontality. As discussed further below, these parallel analyses provide further support for our theory that the inclusion of major societal groups is a key factor, distinct from participation, in the adoption of horizontal effect.

To test Hypothesis 2 concerning the effect of conflict on the probability that horizontality will be adopted, we include the variable Conflict intensity, the UCDP variable employed by Fruhstorfer and Hudson (Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022) discussed above, which measures the mean level of armed conflict intensity in the drafting year and the two prior years.Footnote 14 The UCDP defines armed conflict as a contested incompatibility concerning government (type of political system, replacement of the central government, or a change in composition) and/or territory (change from one state to another in the control of territory in an interstate conflict, or demands for secession or autonomy in an internal conflict), where the use of armed force between two parties results in at least twenty-five battle-related deaths. One of these parties must be the government of a state, defined as an internationally recognized sovereign government whose sovereignty is not disputed by another internationally recognized sovereign government that previously controlled the territory. The dataset includes information on conflicts varying by parties involved, including between states (interstate), a state and a non-state group outside its territory (extrastate), the government of a state and opposition groups with intervention from other states (internationalized internal armed conflict), and the government of a state and internal opposition groups without intervention from other states (internal armed conflict) (Gleditsch, et al. Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002).

With two variables, we account for international pressure to increase minority rights protection and, likewise, the possibility that public posturing vis-à-vis NGOs and foreign states actually drives the inclusion of horizontality provisions. First, Development aid, based on data from the World Bank, is the mean level of official and development aid as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). In addition, we include a dummy variable coded by Fruhstorfer and Hudson (Reference Fruhstorfer and Hudson2022), IO influence, indicating whether the United Nations Department of Peace Operations (UNDPO) or the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (UNDPPA) had an official presence, or whether a mission from a regional governance organization was involved. We also control for several factors that prior research indicates are likely to impact popular attitudes about minority rights. The level of Democracy, or Polyarchy, is measured by V-Dem as including free and fair elections and inclusive citizenship. In general, citizens in a democracy should be more likely to support minority rights, and applying duties to private actors could be another such favored protection. Ethnic fragmentation measures the ethnic, linguistic, and religious heterogeneity within a society (Alesina et al. Reference Alesina2003). An increase in the measure indicates an increase in the probability that two randomly selected individuals are members of different groups. On the one hand, societal fragmentation could be associated with a greater probability that individuals and groups are fighting for increased minority rights, which may include horizontality. At the same time, greater societal fragmentation may undermine the kind of mutuality we argue is needed to adopt horizontality. We include this control but are agnostic as to the result because we want to allow for the possibility that the dynamics related to minority rights are distinct from those of horizontality.

We also recognize that a country’s legal tradition may influence drafters’ approaches to a constitutional project. Specifically, because in common law systems the judiciary is generalist, dealing with all kinds of law, the idea of granting courts the power to apply constitutional law in what are traditionally areas of private law is not likely to be as disconcerting to constitutional drafters. There is also less ground for “turf wars” between private lawyers and public lawyers. Common law judges are also more accustomed to what horizontality asks them to do – balancing – and the description of their work as lawmaking.Footnote 15 In contrast, in a civil law system, adopting horizontality is often a much bigger step, as constitutional law will overtake private law, including the specialized private law courts and lawyers initiated into that system (Mathews Reference Mathews2018). Civil law judges also tend to eschew descriptions of their work as lawmaking. We expect that political elites and private groups functioning in these two systems will be influenced by these aspects of their legal traditions in deciding whether to adopt horizontality. We therefore include measures of legal traditions based on colonial history, British colony, and French colony. We provide descriptive statistics for all variables in our models in the appendices. The lack of availability of the controls for all constitutions in our dataset reduced our N to 97. We tested the effect of inclusion on the adoption of horizontality on the full dataset of 137 constitutions, without controls, and inclusion remains significant. Thus, the models are not sensitive to these changes. Because our dependent variable is dichotomous, we use logistic regression, and employ standard errors clustered around the country to account for expected non-independence in the data (Zorn Reference Zorn2006).

Analysis

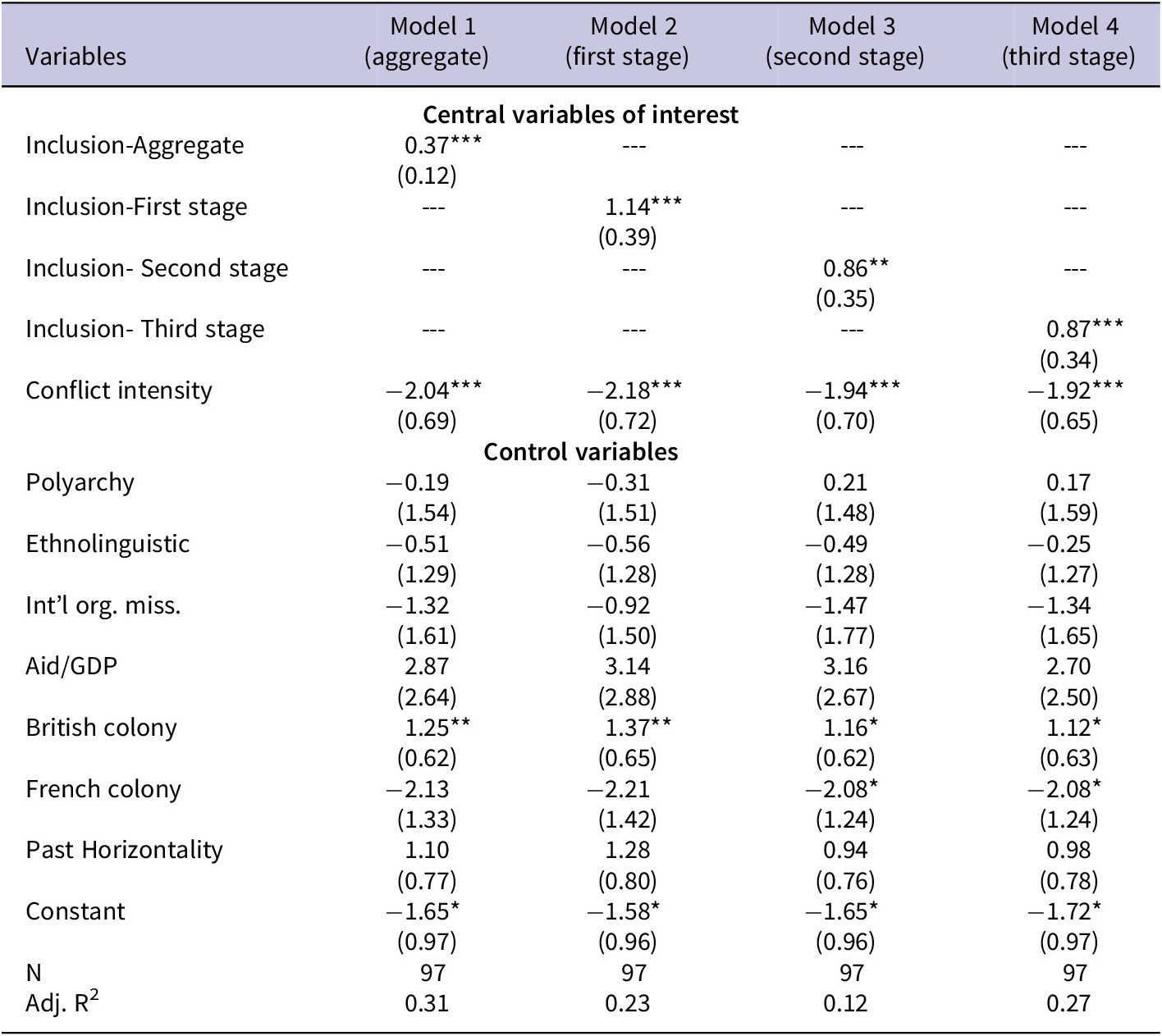

The results of our analysis are displayed in Table 3 below. We begin with our findings concerning our first independent variable of interest, inclusivity, addressing Hypothesis 1. Inclusion-aggregate is significant and positive, indicating that as the level of inclusion across the constitution-making process increases, the probability that horizontality is adopted increases. Similarly, the variables for inclusivity at each stage (Inclusion-first stage, Inclusion-second stage, and Inclusion-third stage) are significant and positive, suggesting that inclusion is important at the time of selecting those who will draft the constitution, when writing the constitution, and at the moment of final enactment.

Table 3. Explaining Horizontality

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses; GDP, gross domestic product.

* p < .1. ** p < .05. *** p < .01

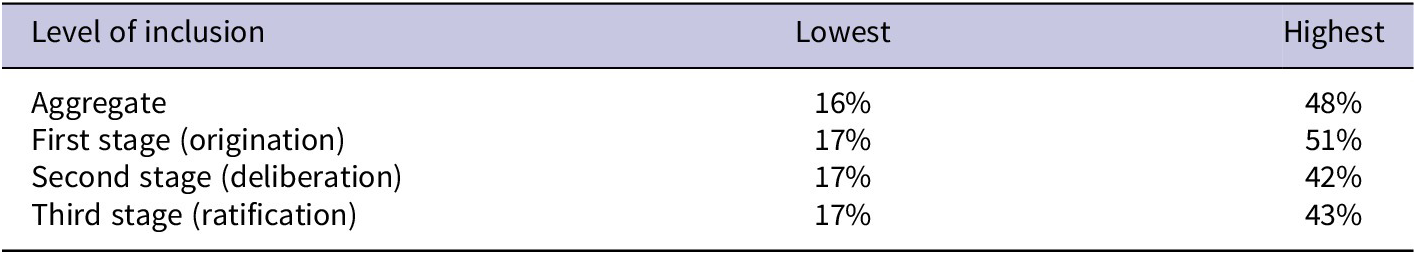

The predicted probabilities indicate that each measure of inclusivity also has substantive significance. Table 4 compares the probability that horizontality is adopted at the lowest level of inclusivity to the likelihood at the highest level for each measure. The predicted probabilities are highly significant (p = 0.001) and the confidence intervals for these two sets of estimates do not overlap. The effect of an increase from lowest to highest level (0 to 6) of the aggregate level of inclusion is 32 percentage points. At the first stage, such an increase (from 0 to 2) is associated with a 34 percentage point increase. At the second and third stage, the impact is lower, 25 and 26 percentage points respectively. Thus, the impact of inclusivity at the first stage is the greatest, and at the second stage is the lowest.

Table 4. Increase in Probability Horizontality is Adopted Moving from No to Full Inclusion

Consistent with Hypothesis 2, Conflict Intensity is also significant and negative. As the level of the intensity of the violence in an armed conflict increases, the probability that horizontality is adopted decreases. In other words, as predicted, horizontality is more likely to be adopted in a relatively peaceful environment. The substantive impact is also significant at its lower levels, and consistent across stages. When Conflict intensity is zero (0), the likelihood that horizontality is adopted is 34% in the aggregate and first stage models, and 33% in the second and third stage models. When Conflict intensity rises one level, the probability of horizontality being adopted decreases by approximately 10 percentage points, to 23% for all models, although the confidence intervals overlap. Once Conflict intensity increases to level 3, the probability drops to about 15%, and the confidence intervals do not overlap. At the maximum level of Conflict intensity, the probability of the adoption of horizontality decreases by about 32–33 percentage points (1% in the aggregate and first stage models, and 2% in the second and third stage models), however, the estimates are no longer significant.

These results support our argument that the process and environment of constitution-making is important for the adoption of horizontality. A remaining question is whether the importance of inclusion holds when we control for the level of public participation. Eisenstadt and Maboudi (Reference Eisenstadt and Maboudi2019) provide evidence that this is the case for democratic outcomes. Our argument above suggests that inclusion, which measures the presence of expert professionals who can articulate the complex public and private interests involved, will remain a significant factor regardless of the level of public participation. Therefore, we conduct several robustness tests to distinguish the effects of inclusion from that of public participation and discuss our findings here. The full results are provided in the appendix.

As is clear from Table 2 above, the measures for inclusion and participation are highly correlated in the first stage of the constitution-making process. In the second stage, the two are moderately correlated. The covariation in the first two stages likely drives the moderate correlation of the aggregate measures. However, inclusion and participation are unrelated in the third stage.Footnote 16 These correlations make it difficult to interpret the results of a model with participation as a control variable. At the same time, the results of these tests provide some support for our argument. Across models for each stage with participation as a control, inclusion is significant while participation is not (Tables 4A and 5A). The results of nested models with inclusion and participation alone, and with all controls but the lagged dependent variable, are also consistent with our theory (Table 6A and 7A). Inclusion is significant and positive in every model at each stage and in the aggregate. However, the aggregate participation variable is not significant in a model without any controls. It is also insignificant in models alone and without the lag at the third stage. Indeed, in the full model (with controls including the lagged dependent variable), participation is not significant in the third stage (Table 8A).

We also ran models interacting inclusion and participation in the aggregate and at each stage of the process (Table 10A). The interaction term was not significant in any model, suggesting that the effects of inclusion are not contingent upon the level of participation. While some of the marginal effects are significant, the confidence intervals overlap considerably (Tables 11A and 12A). In addition, the constituent term for inclusivity is significant and positive, while the constituent variable for participation is insignificant.Footnote 17 These results are further evidence of the importance of a meeting of the minds facilitated by major societal groups. To be clear, we do not argue that participation is not an important factor contributing to the adoption of horizontality in some cases. We assert that horizontality is most likely when a process is inclusive, regardless of the level of direct public participation. We focus on the importance of the inclusion of the widest possible range of interests in the room as articulated by group leaders and assert that this is distinct from the number of individuals in the mass public involved in the process.

Discussion and conclusion

In this first multi-method, cross-national examination of horizontality provisions in constitutions, we find that this potentially transformative constitutional mechanism is more likely to come out of constitution-making processes that are inclusive and that are not plagued by severe conflict. These conditions, we argue, allow for the kind of meeting of the minds that facilitates such an innovation in constitutionalism as horizontal application entails.

The cases we highlight and our accompanying analysis reveal a particular interest in horizontality in issues that affect daily life and that tend to run up against traditional paradigms of constitutionalism. We argue that a driving force behind this development is the representation of diverse interests from across civil society that only find voice in inclusive processes, alongside more common elite voices and interests. Inclusive processes are important for getting certain issues that incline toward horizontality on the table. However, inclusive processes are also requisite insofar as they create the conditions under which private actors seem likely to agree to the potential duties and constraints that come with horizontal application. In a word, it permits a kind of meeting of the minds or mutual commitment from a broad cross-section of society, political elites and members of civil society alike, such that they would even consider reconceptualizing rights and duties.

In these inclusive processes, members of the general public may look to ameliorate power differentials resulting from income inequality, or perhaps formal systems of inequality and customary law when they are not broadly endorsed, as the South African case bears out (Liebenberg Reference Liebenberg and Langford2013). In such horizontal confrontations, Dixon and Ginsburg’s concept of “insurance swaps” (2011) may have some applicability. In particular, citizens may prove more willing to take on new potential duties in exchange for the chance to hold their fellow citizens accountable for constitutional values. At the same time, inclusive constitution-making processes still include political elites and the continual articulation of their own interests. Likewise, horizontality may be leveraged for elite interests, as well. James Tsabora explains a kind of horizontal confrontation in the context of Zimbabwe, in which political elites retain “massive control and regulatory powers in land acquisition, land redistribution and land tenure reform,” often leveraging this power to supersede traditional property rights of private actors (Tsabora Reference Tsabora2016, 216). While the shifting orientation of rights relationships in horizontality renders the well-established insurance model an insufficient explanation of these dynamics, elites still stand to benefit in certain ways from horizontal application as well. Depending on the context, the rights and duties accrued may as a practical matter prove asymmetric across different parties. As the ultimate doctrinal form of horizontality is typically left to the courts and subsequent political-legal developments, we hope that our analysis of this phenomenon’s origins lays the foundation for a future examination of courts’ responses to the varied interests at play by comparative judicial politics scholars.

In reshaping the very relationships underlying rights and duties in a polity, horizontality provisions create a different space in constitutional politics and so must be studied on their own terms. This kind of reshaping of rights and duties, where private actors stand both to gain and to face new limitations, we argue, is most likely when there is powerful articulation of the various diverse interests in play, such that a mutual commitment from a broad cross-section of society may be secured at the negotiating table. Ultimately, this empirical finding about the importance of inclusivity in driving pivotal constitutional change calls up a parallel normative lesson, namely, a republican understanding that the governed should have some say in determining the laws under which they will be governed, particularly in important decisions of constitutional politics (Bambrick Reference Bambrick2020). When it comes to the reshaping of rights and duties of citizens through horizontality, the broad representation of diverse voices from society is crucial.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2024.15.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Bowie, Daniel Brinks, Todd Eisenstadt, Anna Fruhstorfer, Thora Giallouri, Alexander Hudson, Monica Lineberger, Tofigh Maboudi, Banks Miller, Francesca Parente, Raul Sanchez-Urribarri, Mila Versteeg.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available at the Journal of Law and Courts’ Dataverse archive.