Despite narratives of union decline and worker quiescence due to globalization and automation, many countries have seen renewed strike activity in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unions representing public and private sector workers in various countries have mobilized for improved compensation, job stability, and adherence to existing agreements. This renewed mobilization has raised questions about whether there could be a broader wave of union organizing or whether such actions are likely to fizzle out.

Public support is important for determining whether strikes achieve their objectives, as it enhances the leverage of workers during negotiations over working conditions, salaries, and other goals.Footnote 1 Labor strikes can generate public support for workers, but they can also engender a backlash against them. Only a few studies have looked at how labor actions shape public opinion, and they have mostly focused on the United States. Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu, and Reich (Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu and Reich2021) demonstrate that direct exposure to teacher strikes increased public support for workers and unions. In contrast, the effects of strikes in the private sector have been more varied (Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2024).

While this research represents a valuable initial step toward understanding the consequences of strikes, it does not fully consider the real-world implications of labor actions. Strikes do not happen in a vacuum and both strikers and their opponents (i.e., government agencies, business leaders, and conservative media outlets) convey messages in the public sphere—especially in the media—trying to affect public opinion in favor of or against the strikes. The importance of public support for unions and striking workers has led to a strategic contest over how union activities are framed (Brimeyer, Eaker, and Clair Reference Brimeyer, Eaker and Clair2004). Labor unions employ communication teams to convey that their actions represent rightful resistance and to garner public support for addressing legitimate grievances. These teams utilize press releases, social media, and public demonstrations to influence public opinion (Clark Reference Clark2010; Manning Reference Manning1998). In contrast, employers often leverage the media to discredit strikes, frequently portraying unions or their leaders as pursuing narrow, self-interested goals.

How, then, do the framings of strikes affect support for unions and striking workers? Kane and Newman’s (Reference Kane and Newman2019, 997) experimental study demonstrates that negative frames resonate strongly, providing evidence that media portrayals of union members as “overpaid, greedy, and undeserving of their wealth” reduce support for unions and pro-union legislation in the US. However, no experimental research (that we know of) has yet examined how competing real-world pro-strike messages on labor grievances and anti-strike messages on political opportunism through unions influence public support for strikes and the labor movement. Moreover, there is little work on public reactions to strikes outside the US.

This paper addresses these gaps by exploring the effects of messages conveyed by political actors involved in teacher mobilization in Mexico. We focus on the Mexican case for two reasons. First, this case is representative of other cases in the developing world where teacher strikes engender similar political dynamics. Teacher strikes are common in Mexico, and the labor grievances associated with these strikes, such as unpaid salaries, as well as allegations that strikes are motivated by the political ambitions of union leaders, are prevalent in several countries across Latin America (and beyond), thus enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, teachers are not the only labor sector on strike in Mexico, as the country has witnessed an uptick in strikes across various sectors (Fortuna y Poder 2024; Martínez Reference Martínez2023). Second, the powerful position of the Mexican teachers’ union (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, SNTE) in the country’s politics makes Mexico an important case in its own right for understanding the politics of teacher strikes.

We employ an original, preregistered survey experiment to study different framings of strikes on public opinion. Our paper’s innovation is to conduct an in-person survey experiment to study various strike frames on attitudes toward unions and workers outside the US. We present respondents with different vignettes containing information on strike occurrence, and messages conveyed by striking teachers and their opponents to explain the reasons why the strike happened. We constructed simple vignettes, which were drawn from published news stories and union communiqués, to either discredit or garner support for strikers, an approach that is in line with similar work on social movements (Bonilla and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020) and policy endorsements (Houston Reference Houston2021). To add realism to our experimental treatments, we inform our vignettes using our deep case knowledge of Mexico (based on extensive field research), and we draw on a teacher strike in the state of Tamaulipas in September 2023. Our experiment is embedded in a nationally representative in-person survey in Mexico.

We demonstrate that a pro-strike framing, which emphasizes unpaid salaries, and an anti-strike framing that highlights the political interests of union leaders influence public support for unions and striking teachers. However, the effects of these framings vary across the two outcome variables.

The labor grievances (pro-strike) frame increases support for the teachers involved in the ongoing strike, as respondents are reminded of the valid justifications that trigger such strikes. Nonetheless, this frame does not increase support for labor unions in general, as respondents do not make broader associations between the legitimacy of this particular strike and the labor movement overall. In contrast, anti-strike messaging regarding teachers’ unions—specifically referencing the political interests of union leaders as motivating the strike—does not influence citizens’ support for striking teachers, but it does exert a pronounced negative effect on overall support for unions. We argue that this message activates negative preconceptions and distrust regarding unions, beliefs that are already prevalent in public opinion. The implication of our results is that attitudes toward strikes and unions should be considered as separate outcomes and are likely to be related to different causal processes.

In addition, our experiment also enables the examination of pro- and anti-strike messages within a competitive context that often occurs in the media. When respondents are exposed to both pro- and anti-strike messages simultaneously, the negative framing regarding the political ambitions of union leaders exerts a slightly greater influence on public opinion, resulting in increased opposition to both unions and ongoing teacher strikes. This finding underscores the necessity of investigating pro- and anti-strike messages in competitive environments in future research, particularly in contexts where preexisting attitudes toward unions are more sympathetic.

The Contradictory Political Responses to Strikes

In many countries, including throughout North and South America, teachers’ unions are the largest sector of organized labor. With blue-collar, industrial labor unions in decline, public sector unions—and teachers specifically—have become the leading sector of the labor movement in many countries (Visser Reference Visser2019). Public sector unions play a crucial role in influencing compensation and working conditions through collective bargaining, which—because they are often powerful—can dramatically increase the costs of the public sector payroll (Anzia and Moe Reference Anzia and Moe2015). Teachers are a cohesive sector of labor because they share similar employment and training conditions, standardized salary scales, and often face a single, centralized employer. In Latin America, public school teachers also benefit from a tenure system (or at least strong job protection), providing them with security against employer retaliation during labor conflicts, unlike private sector workers (Bruns and Luque Reference Bruns and Luque2014).

The organizational power of teachers’ unions and their embeddedness in institutions gives them considerable influence over decisions in education policy (Moe Reference Moe2015). However, when negotiations and bargaining fail, unions often resort to work stoppages and strikes. Some scholars recognize the strike as “by far the most important source of union power” (Burns Reference Burns2011, 1). Strikes by teachers and other public sector workers are usually more disruptive than those by private sector workers; in Latin America, teacher strikes often affect the entire education sector and drag on sometimes for weeks or even months, making them a contentious tool (Bruns and Luque Reference Bruns and Luque2014; Murillo and Ronconi Reference Murillo and Ronconi2004).

How do these strikes influence broader public support for strikers and unions? While many scholars have documented spillover effects of protests and social movements, less research has explored the effects of labor strikes on public opinion. Existing scholarship provides two contrasting expectations.

First, strikes might enhance support for worker demands. Strikes can have effects beyond the participants themselves. Scholars of labor action have hypothesized that collective actions like strikes can build new values, solidarity, and class consciousness among workers, especially when union leaders rely on strategies of persuasion and advocate for social justice (Ahlquist and Levi Reference Ahlquist and Levi2013). Research on social movements suggests that large-scale protests can inspire additional waves of mobilization, introduce new frames of thinking, and shift public opinion toward supporting the causes of protesters (Amenta et al. Reference Amenta, Caren, Chiarello and Su2010; Andrews Reference Andrews2004; Collins Reference Collins2024; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011). Social movement protests have often boosted public support for those movements, even in cases where protest turns violent (Enos, Kaufman, and Sands Reference Enos, Kaufman and Sands2019; Madestam et al. Reference Madestam, Shoag, Veuger and Yanagizawa-Drott2013; Mazumder Reference Mazumder2018). Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu, and Reich (Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu and Reich2021) find that striking teachers can build solidarity with the parents whose children they teach, and Lyon (Reference Lyon2023, 11) suggests that teachers’ unions, in making demands, can serve as the basis for “progressive coalition building” that challenges “longstanding economic and political inequalities and increase[s] the rights of marginalized groups.”

And yet, there are reasons to believe that strikes might reduce support for the labor movement. Labor actions have costs, as they disrupt production and service delivery. Research has demonstrated that healthcare strikes negatively affect patient care, manufacturing strikes harm product quality, and teacher strikes negatively affect student performance (Baker Reference Baker2013; Gruber and Kleiner Reference Gruber and Kleiner2012; Krueger and Mas Reference Krueger and Mas2004; Mas Reference Mas2008). Research has also shown that violent protests can increase the resonance of frames of “social control” among elites and the mass public, as occurred in the case of civil rights protests in the 1960s (Wasow Reference Wasow2020, 640).

Teacher strikes in particular impose substantial costs on parents and broader communities through missed classes and learning losses (i.e., students falling behind in their grade level due to a loss of instructional time), potentially creating a backlash. There is likely to be criticism of teachers for the “collateral damage” that strikes inflict on students, with parents seeking childcare when schools are shut down, and children missing classes (Belot and Webbink Reference Belot and Webbink2010; Jaume and Willén Reference Jaume and Willén2019; Naidu and Reich Reference Naidu and Reich2018). Protests by teachers might even prompt middle-class parents and others who have the financial means to pay private school tuition to leave public schools (Narodowski, Moschetti, and Alegre Reference Narodowski, Moschetti and Alegre2016). Moreover, teacher strikes, rather than being motivated by labor grievances, may be a byproduct of the political maneuvering of union leaders. In Argentina, for instance, teacher strikes often occur when leaders in government have partisan identities that are different from those of union leaders, which might diminish public support for the latter since they are seen as being about political disagreements rather than labor grievances (Murillo and Ronconi Reference Murillo and Ronconi2004).

There have only been a few empirical studies on public responses to worker strikes. Research in the US has supported the former hypothesis, suggesting that teacher strikes can increase support for workers and unions more broadly. However, the results have been divergent for public versus private sector unions. Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu, and Reich (Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu and Reich2021), focusing on the consequences of the 2018 education workers’ strikes in states such as West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arizona, Colorado, and North Carolina, provide evidence that face-to-face contact with the striking workers among the most affected population—parents of school-age children—increases support for teachers, unions, and their demands. These teacher strikes also heightened individuals’ interest in labor action, suggesting a potential multiplier effect that could inspire broader labor mobilization. By contrast, the consequences of private sector strikes have been more limited (Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2024).

We focus on how public messaging, particularly through media channels, influences public opinion regarding strikes. Media serve as a critical instrument for conveying information about labor unions to the public. Given the decline in union membership in both industrialized and developing nations over recent decades, a diminishing segment of the population possesses firsthand experience with unions. As a result, many people rely on media coverage to form their opinions about unions and strikes. While prior empirical studies have examined the effects of direct, face-to-face contact with strikes, there has been insufficient attention to the political messaging that surrounds these events, and specifically to how providing information about the motives of strikes shapes support for them. We advance this literature by shedding light on the effects of framings of strikes by unions and their opponents.

The Effects of Political Messages around Strikes

Scholarship on campaigns and public opinion has demonstrated that citizens’ attitudes on different issues can be influenced by how elites frame their messages in competitive media environments (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007). In the parlance of this research, a speaker “frames” an issue by encouraging readers or listeners to emphasize certain considerations above others when thinking about it. A framing effect occurs when different but logically equivalent words or phrases cause individuals to alter their preferences (Druckman and Nelson Reference Druckman and Nelson2003, 730). This has produced a rich experimental literature measuring the direction and magnitude of these effects (Druckman Reference Druckman2004; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Kang, Chu, Stagnaro, Voelkel, Mernyk, Pink, Redekopp, Rand and Willer2023).

In parallel, scholars of protest movements have pointed to the importance of “social movement frames”—messages both to mobilize individuals to participate in protests and also to generate bystander support for them (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2011). Indeed, many scholars argue that successful movements need activists to behave as “signifying agents actively engaged in the production and maintenance of meaning for constituents, antagonists, and bystanders or observers” (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000, 613).

While many scholars have focused on the framing effects of messages from social movements, fewer have looked at the traditional labor movement. And yet, unions have clear incentives to affect public opinion in their favor during strikes, and labor scholars have emphasized how the success of the contemporary labor movement depends on public relations campaigns (Clark Reference Clark2010, chap. 7). For many bystanders, it is hard to discern whether striking teachers have legitimate grievances. These bystanders are likely to be influenced by how the claims of labor grievances are framed. If publics are bombarded with messages about the political opportunism of union leaders, rent seeking, and corruption, bystanders are more likely to become skeptical about the motives behind labor action. By contrast, if unions convey a clear message of legitimate grievances, the public is more likely to support union causes.

Labor unions have communication teams dedicated to conveying the message that they are engaged in rightful resistance and urging the public to support their actions. Union organizations typically have a secretary of press, communication, or propaganda responsible for social media, press releases, and engaging with journalists. In the aftermath of Thatcherism, unions in the United Kingdom were concerned with how they were represented in the media and honed communication strategies to address negative frames (Manning Reference Manning1998). Labor unions, like the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) in the US, have spent tens of millions of dollars on campaigns like the 1996 “America Needs a Raise” campaign, which aimed to “identify the beliefs of its audience [and] tailor its message to the issues and concerns of its members” (Clark Reference Clark2010, 123). In the 2019 Stop & Shop strike in the US, unions representing grocery store workers publicized their grievances and demands to the community, encouraging customers to boycott the stores, join picket lines, and donate food and money (Manzhos Reference Manzhos2019). In the case of the 2012 Chicago teacher strike, unions also interacted directly with parents and students and used frames like striking for “the schools and communities that students deserve” (Charney, Hagopian, and Peterson Reference Charney, Hagopian and Peterson2021).

On the other hand, employers in both the private and public sectors often use public relations and media campaigns to discredit strikes, frequently blaming unions or their leaders for promoting narrow interests. Kane and Newman (Reference Kane and Newman2019) demonstrate that exposure to anti-union rhetoric in the media—portraying unionized workers as overpaid, greedy, and undeserving of their wealth, and drawing a contrast between the compensation of unionized and nonunionized workers—diminishes support for unions and pro-union legislation. Furthermore, these authors show that such rhetoric can nullify or reverse the otherwise positive relationship between worker identity and solidarity with unionized workers. In these anti-union narratives, members of organized labor—historically regarded as advocates for the working class—are depicted as more privileged than “average” workers. These portrayals equate union members to the “undeserving rich” who are not worthy of additional compensation, power, or public support (Kane and Newman Reference Kane and Newman2019, 1001).

The Argument: Framing Labor Action

We use both pro-strike messages about labor grievances and anti-strike messages about the political opportunism of union leaders to identify effects on public support for strikes and the labor movement in our experimental study. We argue that the messages conveyed by strikers and their opponents alter the preferences of bystanders on the role of unions and support for strikes. We have two broad expectations.

First, we argue that a framing strategy based on labor rights and the legitimate grievances of workers increases support for union causes. It has been well documented that collective bargaining rights and low salaries are the primary reason that teachers in many countries decide to go on strike (Etchemendy and Lodola Reference Etchemendy and Lodola2023). Labor unions use various communication strategies to raise awareness about their labor grievances and how long they have waited for these grievances to be addressed. Our expectation is that the labor grievances frame would increase support for both striking workers and unions overall.

We focus on salary-related issues, as these are the most common grievances driving strikes across various contexts. In the US, low salaries have been the main cause of labor actions, especially among teachers during the 2018 Red State Revolt (Blanc Reference Blanc2019). We expect these grievances to generate public sympathy for workers. Messages about delayed or unpaid wages by employers are especially significant. The late payment of salaries and irregularities in the teacher payroll afflict many low- and middle-income countries (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, Winthrop, Golden and Ndaruhutse2012). They signal that unions are engaged in rightful resistance because unions are highlighting problems in the government involving mismanagement of resources and failure to comply with existing agreements. We argue that claims based on the late payment of salaries are especially likely to engender public sympathy.

Yet we also argue that legitimate grievances could be offset by the negative framings of union leaders organizing strikes to advance their own political aspirations. The concept of “political opportunism” refers to union leaders taking advantage of the position they hold in their organization to advance their own political or economic interests. Some union leaders seek to hold public office, and strikes can signal their capacity to mobilize votes. Teacher protests may be perceived as being driven by the partisan identities of union leaders rather than an organic expression of grassroots discontent, as has been shown in Argentina (Murillo and Ronconi Reference Murillo and Ronconi2004). Parents may associate these political ambitions with low learning outcomes and corrupt practices in the education sector; in developing democracies like Mexico, union leaders may influence which teachers are hired and promoted (Nájar Reference Nájar2014). In such contexts, we argue that anti-strike information on the political interests of union leaders would provoke strong negative sentiments and decrease support for the labor movement overall and for the striking workers.

To be sure, not all teachers’ unions have leaders who are politically opportunistic; a variety of different organizational structures and political practices have been documented (Chambers-Ju Reference Chambers-Ju2024). Indeed, some teachers’ unions are more akin to social movement unions that are relatively democratic internally and make broad-based demands that reflect the interests of the rank and file (Finger and Gindin Reference Finger and Gindin2015). However, opponents of unions often criticize union leaders for being politically motivated and corrupt. Employers who seek to discredit a strike are likely to use this frame, highlighting differences between the union leadership and the rank and file. Barnes, Kerevel, and Saxton (Reference Barnes, Kerevel and Saxton2023, 114–15) have shown, in their study of attitudes toward working-class representatives in the legislature, the resonance of the political opportunism frame among survey respondents. While many regard working-class representatives as having the potential to understand them and represent their interests, they also express concern that union leaders may be beholden to political parties and prone to corruption.

Our experimental research design aims to test the effects of the labor grievance and political opportunism frames on the outcomes of support for ongoing strikes and support for unions overall. We expect that when information is provided on specific grievances of striking teachers, respondents increase their support for both unions and teacher strikes. By contrast, when respondents are introduced to negative information about the political ambitions of union leaders, they are expected to reduce their support for unions and striking teachers.

H1: Information on labor grievances increases support for labor unions and striking teachers (compared to no information and/or anti-strike information about strikes and unions).

H2: Information on the political interests of union leaders decreases support for labor unions and striking teachers (compared to no information and/or pro-strike information about strikes).

In addition to the theoretical arguments presented, we outline two supplementary implications of our theory. First, we examine the moderating influence of prior attitudes on the strength of our effects. Existing literature on framing suggests that the impact of framing effects is contingent upon individuals’ preexisting attitudes regarding various issues. Frames that introduce novel information, which respondents may not have previously considered, tend to resonate more strongly where prior opinions are ambiguous, allowing for easier reframing of attitudes (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2010; Druckman and Leeper Reference Druckman and Leeper2012). Consequently, stronger framing effects are anticipated where individuals exhibit weaker prior opinions, as their attitudes are more susceptible to change.

Building on this premise, we anticipate that the magnitude and intensity of these framing effects will differ across two distinct outcomes. Specifically, we propose that our experimental manipulations will exert a greater influence on support for an ongoing strike compared to general support for union influence. Our treatments aim to deliver new information regarding these strikes, likely resulting in attitude shifts in both directions. Information highlighting legitimate worker grievances is expected to enhance support for the ongoing strike, while negative information regarding political motivations may elicit backlash.

Conversely, considering the prominent role of unions in politics, citizens are likely to possess well-established beliefs about labor unions, rendering their attitudes less pliable. Public support for labor unions is significantly shaped by deeply entrenched views regarding unions and their societal roles, which are influenced by historical legacies, including the incorporation of the labor movement into political parties (Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1991). Thus, we anticipate that both pro- and anti-strike framings will exert effects of diminished magnitude on overall public support for unions compared to the support for striking teachers.

Furthermore, we also consider our two framings in a competitive context. Previous experimental research has examined issue framing in such contexts by presenting individuals with opposing frames (Brewer and Gross Reference Brewer and Gross2005). The real-world impact of any given frame on opinion can be neutralized by the introduction of a counterframe—that is, a second frame that rebuts the first (Sniderman and Theriault Reference Sniderman, Theriault, Saris and Sniderman2004). A typical communication environment involves competing sides promoting alternative interpretations of an issue (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007). This mirrors real-world settings in the media and provides the strongest test of whether pro- or anti-strike frames prevail in winning the hearts and minds of the public, or if these frames cancel each other out. By putting frames in competition, it is possible to distinguish their strength.

Teachers’ Unions and Strikes in Mexico

We have focused on the Mexican case to study the framing of teacher strikes for two reasons. First, Mexico serves as a case that could represent other developing democracies that have both a politically active teachers’ union and frequent teacher strikes. Teacher strikes are common in Mexico and are widely covered by the media. Salary grievances are often the issue driving strikes in Mexico, making our results regarding the framings of labor grievances widely generalizable to any country where teachers strike due to being underpaid or not paid on time. The Mexican teachers’ union, SNTE, is a prominent union in the minds of Mexican citizens, and many have well-formed opinions about it. As we demonstrate below, public opinion is divided regarding unions and strikes, creating an ideal setting to test our arguments about the positive and negative framings of strikes by different actors.

Second, the Mexican case is significant in its own right. SNTE has played a crucial role in the country’s political landscape for decades, and the public’s attitudes toward it warrant examination. Scholars have studied how SNTE mobilizes votes (Larreguy, Montiel Olea, and Querubin Reference Larreguy, Olea and Querubin2017) and how union locals play a role in policy implementation (Coyoli Reference Coyoli2024). However, the distinctive features of SNTE also raise valid concerns about the extent to which our findings can be generalized to other contexts. We elaborate on the scope conditions of our theory in the discussion section.

SNTE currently unites more than 1.5 million teachers and is the most powerful labor union in the country. Yet this organization, like other unions in Mexico, has been stigmatized for its associations with authoritarian rule, labor bossism, and corruption (Middlebrook Reference Middlebrook1995). SNTE was founded in 1943 when the dominant party regime of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) established organizations to control workers and peasants. During the seven decades of PRI rule (1929–2000), SNTE distributed benefits to members through patron–client relations and provided the crucial service of electoral mobilization to the ruling party, usually avoiding labor conflict by maintaining authoritarian control over its members (Chambers-Ju and Finger Reference Chambers-Ju, Finger, Moe and Wiborg2017). SNTE infamously sold teacher positions and made promotions dependent on attendance at political rallies, allowing it to deliver blocs of votes to the governing party but reducing the quality of teachers (Schneider Reference Schneider2024).

However, in the 1980s, following democratization and economic turmoil, SNTE began to weaken and a dissident faction, Coordinadora Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación (CNTE), emerged, demanding union democracy and higher teacher pay (Cook Reference Cook1996; Tarlau Reference Tarlau2022). While the dissidents were demobilized in the 1990s, they reemerged in the late 2000s. During the administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto (2012–18), an education reform was passed that established standardized teacher evaluations for hiring and promoting teachers that many teachers regarded as setting a one-size-fits-all standard that did not take into consideration linguistic and cultural diversity or socioeconomic disparities (Bracho Reference Bracho2019), while ignoring the proposals of teachers for “curricular, infrastructural, and pedagogical” reforms (Tarlau Reference Tarlau2022). Peña Nieto’s reform triggered a major CNTE-led protest and strike wave in 2013–15, as many teachers perceived the reform as a threat to labor rights, while union leaders saw it take away their discretionary power to control hiring and promotion.

Since 2013, the dissident faction has routinely organized strikes, mostly occurring in states where CNTE is strong (namely the southern, less developed states of Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Michoacán). At the same time, there are also periodic strikes in states where CNTE is either weak or nonexistent, and where teachers are organized by SNTE. Decisions on teachers’ salaries and benefits are decentralized to the state level (Mexico has 32 federal entities), so local strikes usually target state governments. Major SNTE-led strikes occurred in 2022–24 in the states of Tamaulipas, Baja California, Chiapas, Hidalgo, Zacatecas, Oaxaca, Guerrero, and Mexico.

Common causes of strikes include low salaries, unpaid salaries, and reductions in benefits. Although household surveys show that teacher salaries in Mexico have increased steadily since the 1990s and are more closely on par with the salaries of other professionals—at least compared to other Latin American countries (Elacqua et al. Reference Elacqua, Hincapié, Vegas, Alfonso, Montalva and Paredes2018, 20)—teachers often endure irregularities in the management of their payroll and are not paid on time. Demands also include the resignation of officials responsible for the conflict or those who have failed to resolve it.

Teacher strikes are widely covered in television, print, and social media. Even the state-level strikes have the potential to become a national political spectacle. The web scraping of all news articles in the online versions of national newspapers El Sol de México and El Economista yielded 1,281 articles related to SNTE and CNTE from 2020 to 2024. Of these articles, 302 (24%) directly mentioned strikes and protest actions. This demonstrates how teacher protests are widely covered in the media and frequently associated with the teachers’ union.

Public opinion data indicate that citizens are widely knowledgeable of strikes. For instance, a poll conducted during the 2013 strike wave indicated that 60% of citizens in the Mexico City metropolitan area were directly affected by CNTE protests and 63% said that they were aware of the demands of the striking workers (Parametría 2013). In this survey, a narrow majority of the public sympathized with the striking workers. Fifty-one percent believed that the marches occurred because “the authorities did not respond to the teachers’ demands,” while 47% believed that “[i]t is customary for teachers to protest when they do not agree with something.”

Available survey data show that public opinion is divided over labor unions and strikes: citizens recognize the importance of union representation for worker rights, but tend to distrust unions and union leaders. In 2023, Latinobarómetro found that only 31% of respondents indicated that they feel “a lot” or “some” trust toward unions in Mexico, while 62% indicated that they have “little” or “no” trust. These numbers are similar to Latin America as a whole (Barnes, Kerevel, and Saxton Reference Barnes, Kerevel and Saxton2023; Latinobarómetro 2023). A study conducted by Parametría (2013) showed that 55% of Mexicans believe that SNTE has a negative influence on public education, while less than three out of 10 (26%) think that the teachers’ union has a positive impact on teaching.

Regarding public perceptions of the beneficiaries of actions by labor unions, overall 46% believe that the main beneficiary is the union leader, 33% the workers, 10% the politicians, and 10% the employers or companies (COP UVM 2019). However, in that same survey, 71% of respondents indicate that it is important for a union to participate in the political life of the country. Additionally, 54% believe that workers who are entering the labor market would be interested in joining a union, 33% think they would be slightly interested, and 10% believe they would not be interested at all (COP UVM 2019). Again, these data demonstrate the ambivalence of public opinion toward unions. There is sympathy for unions, which might be rooted in legacies of populist mobilization in Mexico dating back to the Mexican Revolution during the early twentieth century.Footnote 2 On the other hand though, well-documented cases of union leaders using labor organizations to benefit themselves and their family members have also colored public perceptions.

Unions in Mexico invest heavily in public relations to influence public opinion. SNTE, CNTE, and other unions have press and social media teams to convey messages. They seek to inform the public about their actions via press releases, social media posts, blog posts, and personal communications with journalists (see SNTE’s blog and its account on Twitter/XFootnote 3). When strikes take place, unions launch public relations campaigns to explain the untenable conditions that lead to strikes. They seek to clarify their list of demands (pliego de petición) to mass publics and shed light on the lack of government action to address them. SNTE has been particularly active in denouncing the late payment of salaries and demanding that the government comply with the terms of its labor contracts.

Given that state-level teacher strikes often target state education secretaries responsible for the payment of salaries, these officials have talking points of their own that they use to rebut the basis for teacher strikes. State education secretaries often frame teacher strikes in relation to the political ambitions of union leaders, who routinely use their platform to pursue political office. At the national level, media conglomerates in Mexico like Televisa and TV Azteca, along with business-funded education advocacy organizations like Mexicanos Primero, have highlighted the frames of unions as greedy, corrupt, and politicized. Anti-union messages also involve denouncing teachers for demanding even more pay or bonuses when their salaries are already relatively high, and they have stressed the harmful effects of teacher strikes. According to Valdés Vega (Reference Valdés Vega2020, 178), a television and radio campaign in 2013–14 by the largest media conglomerates against SNTE “was so big and so negative … that rural and urban teachers alike said they were ‘ashamed to tell people they were teachers.’”Footnote 4 Education politics in Mexico increasingly takes place in the context of competing mass appeals for support.

Research Design

The goal of our empirical analysis is to test whether pro- and anti-strike information affects public support for striking teachers and labor unions in general, while holding constant citizens’ baseline expectations about unions and strikes. Studying the ways that information used in media campaigns surrounding strikes influences public opinion is complicated by endogeneity issues. Unobserved political and economic factors might be correlated with citizens’ exposure to strike messages and their attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. For instance, unions, governments, and businesses may target specific subgroups with their messages, making it difficult to estimate the causal effect of these framings.

To mitigate these challenges, we employ a survey experiment with randomized treatments of simple pro- and anti-strike messages. The experiment is embedded within an in-person survey conducted on a nationally representative sample of Mexican adults (18 years and older) by the survey firm Data Opinión Pública y Mercados. The sample size consists of 1,010 respondents, grouped into a hundred survey clusters. Enumerators asked participants questions related to multiple independent projects. Additionally, the survey collected demographic and political information, including socioeconomic status, education level, gender, age, and partisan identification.

Tamaulipas Teacher Strike

We focus on the 2023 Tamaulipas teacher strike for three reasons. First, focusing on a real-world strike occurrence—rather than a hypothetical vignette—adds crucial realism to the treatment conditions (Seawright Reference Seawright2016). While it is unlikely that this strike was previously known to all respondents, it received considerable national media attention.Footnote 5 Its duration and the demands made during the strike share similarities with other recent state-level strikes in Baja California Sur, Guerrero, Zacatecas, and Oaxaca.Footnote 6 As a result, the occurrence of such a mobilization was familiar to respondents and remained fresh in their minds, even outside Tamaulipas, when the survey was conducted.

Second, the demands in the Tamaulipas strike generalize well for understanding teacher strikes throughout Mexico. While the large CNTE-led strike wave in Mexico in 2013 targeted a new teacher evaluation policy and other labor reforms that have been unevenly adopted in the region, the Tamaulipas strike focused on unpaid teachers’ salaries and problems related to working conditions, which are common grievances in many countries. Given the character of the Tamaulipas strike, we believe that our conclusions are applicable to other countries in Latin America and developing democracies where similar problems exist.

Lastly, the Tamaulipas strike offers a possibility to contrast competing pro- and anti-strike discourses commonly broadcast on the media across Mexico and Latin America. Union leaders in Tamaulipas stressed grievances related to unpaid salaries and the lack of attention from the state’s education secretary (Animal Politico 2023). By contrast, both government officials and local analysts blamed opportunistic and politically motivated union leaders for using strikes to advance their own personal interests. In particular, accusations were aired about union leaders wanting to acquire control over key positions in the state education secretariat and to launch political careers ahead of the 2024 elections (Escamilla Reference Escamilla2023). Such accusations of political opportunism among union leaders are common in the media in Mexico. Our treatments aimed to extract these existing framings from the public discourse (as in H1 and H2) and see how they affect public support for unions and striking teachers. We further explain the creation of our experimental treatments in online appendix B (Chambers-Ju and Trasberg, Reference Chambers-Ju and Trasberg2025).

Treatment Conditions

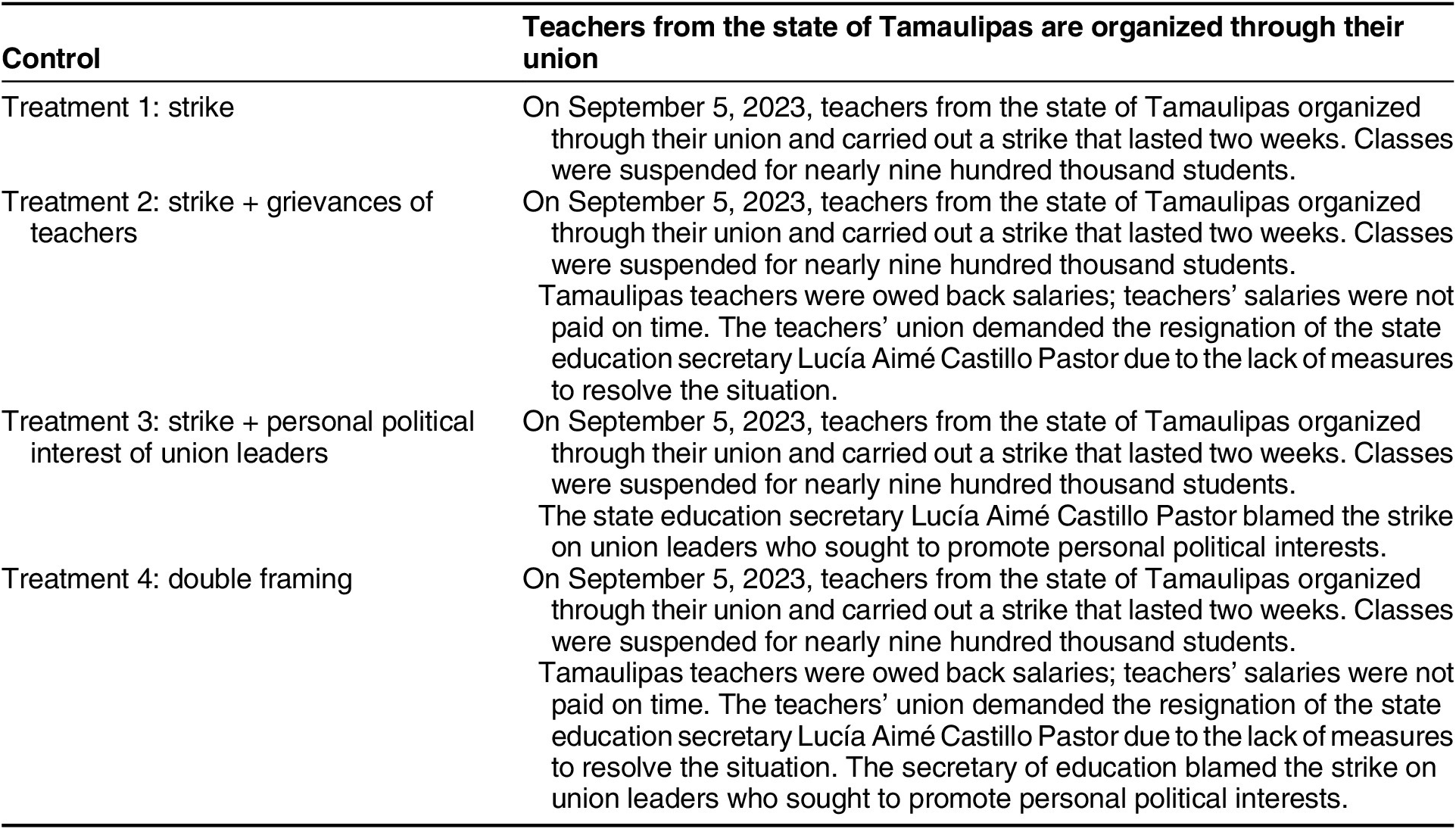

Respondents were presented with randomly assigned real-world vignettes on the occurrence of the teacher strike in Tamaulipas and different messages conveyed by striking teachers and their opponent, the state government. Our experiment includes one control condition—which does not mention a strike—and four treatment conditions that describe the Tamaulipas teachers’ strike in different forms (see table 1). The control condition displays descriptive information about teachers being unionized. This is crucial for separating out the informational effect of simply mentioning unionized teachers from that of mentioning the actual occurrence of the strike.

Table 1 Control and Treatment Conditions

The first treatment condition provides respondents with information on unionization but also describes the teacher strike in Tamaulipas. In the Mexican context—where such teacher mobilizations are common—we do not expect this simple information to significantly alter preferences. SNTE and CNTE strikes are widely covered in the national media, and citizens often report having firsthand exposure to, and preexisting opinions about, strikes and teachers’ unions. However, treatment 1 is crucial for our empirical design in testing H1 and H2 on framing effects, as it allows us to distinguish the impact of simply mentioning labor action from that of pro- and anti-strike framings.

To test hypotheses about pro- and anti-strike framing effects and how much they resonate, we extracted framings from the public discourse in the media. First, we used the union discourse that they had legitimate labor grievances, which triggered the strike. Treatment 2 presents respondents with the information on strike occurrence plus teachers’ grievances related to pay. We also found multiple mentions of analysts blaming politically motivated union leaders for using strikes to advance their own interests. The third treatment presents respondents with information on strike occurrence plus information on the political interests of union leaders as being the main motivation for the strike. The fourth treatment condition presents respondents with a double framing that includes both the grievances of teachers and the political interests of union leaders. We provide balance tests for our experimental treatments in online appendix A, table A6 (Chambers-Ju and Trasberg, Reference Chambers-Ju and Trasberg2025).

Outcome Variables

After respondents were exposed to these randomly assigned vignettes, respondents were asked whether they supported striking teachers specifically and then whether they supported union influence in Mexico in general. Following Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu, and Reich (Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu and Reich2021), we capture respondents’ preferences for union influence and support for striking teachers through two outcome variables. To measure support for the labor movement in general, we asked whether respondents would like the labor movement to have more influence in the future (“Thinking about unions in general, would you personally like unions in Mexico to have more influence, the same influence, or less influence than they have today?”). This variable ranges from one to five (“1. Much less influence,” “2. A little less influence,” “3. The same influence,” “4. Somewhat more influence,” “5. Much more influence”), and it has a mean of 3.17 with a standard deviation of 1.4. We then asked respondents to what extent they supported the striking teachers in Tamaulipas (“Do you support or oppose the teachers who are striking in Tamaulipas?”). The responses varied on a scale of one to seven, where one means total opposition and seven means complete support. This variable has a mean of 4.46 with a standard deviation of 2.4.

Results

Given the structure of our outcome variables, all statistical tests are conducted using ordinal logistic regression. We examine the effects of our control and treatment conditions on the two outcomes of interest. To test H1 and H2, we assess whether there is a statistically significant difference between (1) the anti- and pro-strike treatments and the control condition, and (2) the pro- and anti-strike treatments themselves.

Since we are interested in average treatment effects—specifically, the statistical differences both between the control and treatment conditions, as well as between the anti- and pro-strike messages—we present separate models, using the control and pro-strike conditions as reference categories. Additionally, using the pro-strike frame as the reference category allows us to interpret the results of the double framing, helping to establish how much attitudes shift when negative information is added to positive information.

In table A5 of online appendix A, we provide descriptive statistics for both the survey population and the general population of Mexico (Chambers-Ju and Trasberg, Reference Chambers-Ju and Trasberg2025). Our survey is aimed at being nationally representative in terms of age, sex, and education. We achieved this for the first two variables, although there are some imbalances in education levels when comparing our survey results with census data. As a robustness check, we use weights for the education variable to correct for this imbalance (see tables A1 and A2 in online appendix A), while our main models in this section are presented without weights. Additionally, appendix A also presents models both with and without controls for sociodemographic variables, including age, sex, income, education, and partisanship. Our results remain consistent when adding both weights and control variables.

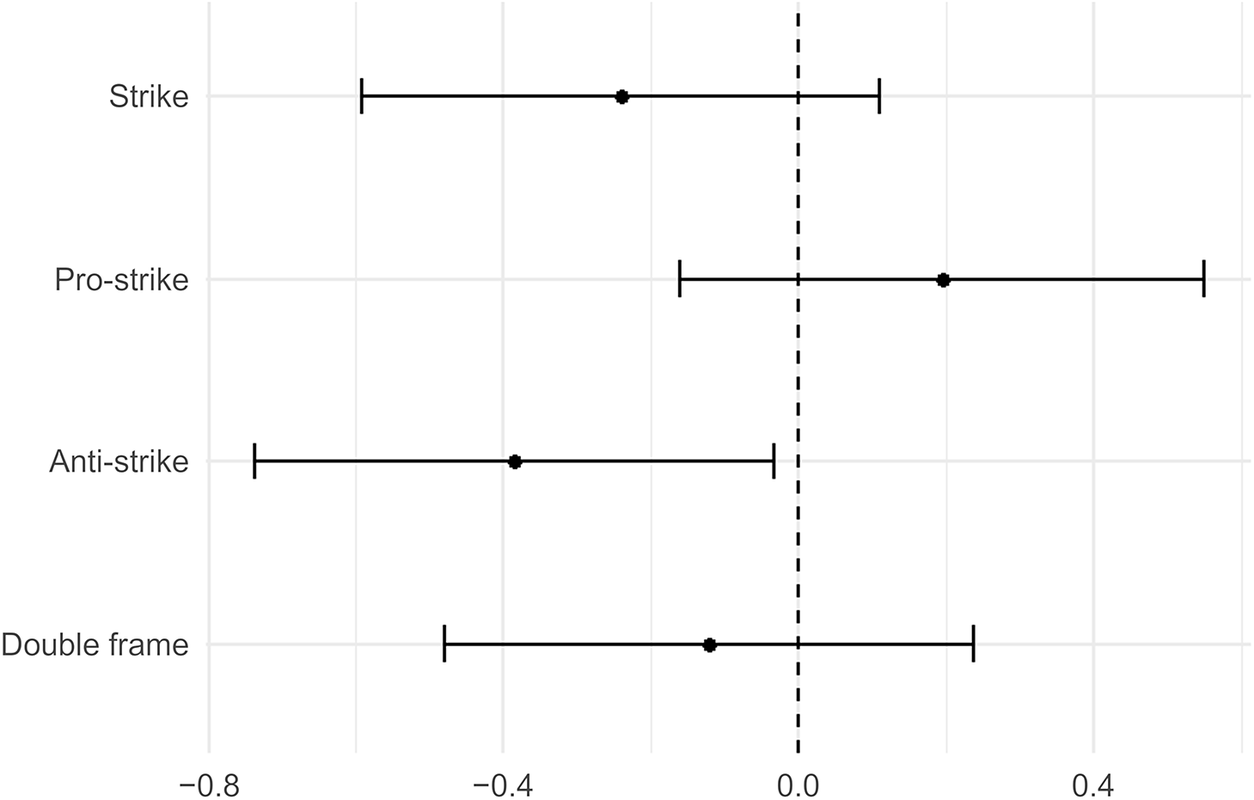

Figure 1 presents the effects of our four experimental treatments on support for union influence, using the control condition as the reference category. The coefficients represent the estimated effects of moving from the control to the four treatment conditions. The pro-strike and anti-strike treatments in figure 1 show the effects of “teacher grievances” and “leader political interests” treatments on union support. Full results, with and without socioeconomic and political control variables, are presented in table A1 in online appendix A.

Figure 1 Support for Union Influence by Treatment Condition (Control as Reference Category)

Notes: The plotted values are unstandardized coefficient estimates from the ordered logistic regression model. The treatment effects represent the estimated effects of moving from the control to the four treatment conditions. The bars around the point estimates represent 95% confidence intervals. N = 976.

As we expected, simple information on the occurrence of teacher strikes is not statistically different from the control condition. However, the analysis provides strong evidence that the negative, anti-strike treatment (the political interest of union leaders) has a negative effect on union support (H2). By contrast, while the positive message on union grievances trends in a positive direction, the effect is insignificant (p = 0.28). The effect of the positive frame remains inconclusive due to low statistical power. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the double framing is not statistically different from the control condition, indicating that neither framing dominates over the other.

However, this analysis does not establish whether there is a statistically significant difference between the pro- and anti-strike treatments themselves. In figure 2, we use the pro-strike treatment as the reference category. Moving from the pro-strike condition to other treatment conditions, we find that the simple strike condition, anti-strike framing, and double framing (only at the 0.1 level) are statistically different from the pro-strike condition. This demonstrates that pro- and anti-strike conditions shift public opinion in opposite directions. It also shows that when an anti-strike message about union leaders’ political interests is added to the pro-strike framing (double framing), public opinion shifts in a negative direction.

Figure 2 Support for Union Influence by Treatment Conditions (Pro-Strike as Reference Category)

Notes: Plotted values are unstandardized coefficient estimates from the ordered logistic regression model. The treatment effects represent the estimated effects of movement from the pro-strike condition to the other treatment conditions. Bars around point estimates represent 95% confidence intervals. N = 976.

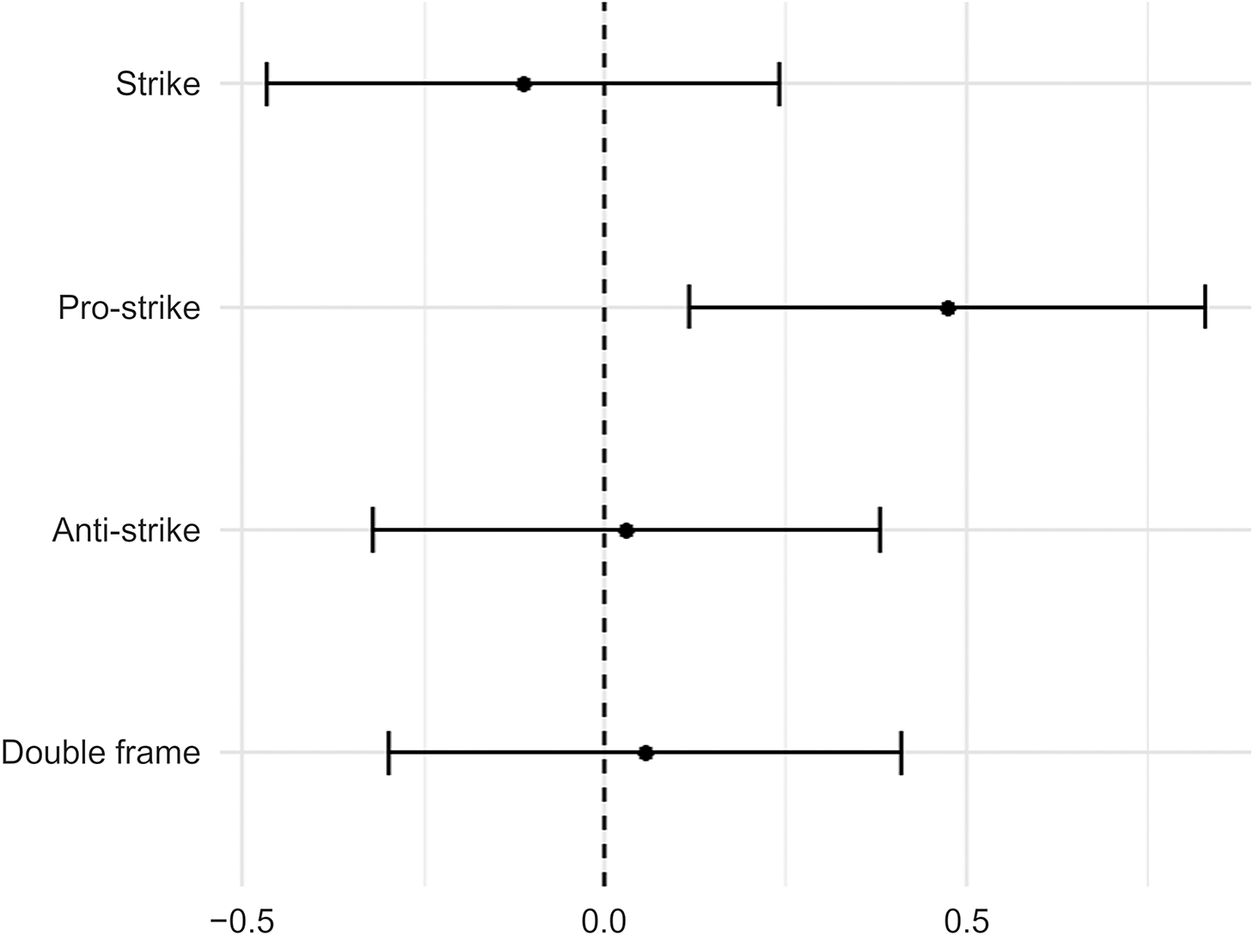

Figure 3 presents the analysis of the second outcome variable: support for striking teachers, with the control condition as the reference category (full results with and without controls are presented in table A2 in online appendix A). The insignificant results of the strike condition (compared to the control condition) are replicated in this analysis. However, the analysis clearly supports H1, showing that information on labor grievances increases support for striking teachers. There is a statistically significant difference between the control and pro-strike framings at the 0.01 level.

Figure 3 Support for Striking Teachers by Treatment Condition (Control as Reference Category)

Notes: The plotted values are unstandardized coefficient estimates from the ordered logistic regression model. The treatment effects represent the estimated effects of moving from the control to the four treatment conditions. The bars around the point estimates represent 90% and 95% confidence intervals. N = 961.

To determine whether there is a significant difference between the pro- and anti-strike treatment conditions, we used the pro-strike condition as the reference category in figure 4. Moving from the pro-strike condition to other treatment conditions, we observe that all conditions shift public opinion in a negative direction, showing less support. We interpret this as evidence that information about labor grievances significantly shifts public opinion in favor of the strikers’ objectives, providing a boost in public support. This analysis also demonstrates the power of pro-strike and anti-strike framings in the competitive context. When a negative message about union leaders’ political interests is introduced (double framing), public opinion shifts in a negative direction. This suggests that anti-strike messages may outweigh pro-strike ones in competitive contexts in Mexico.

Figure 4 Support for Striking Teachers by Treatment Condition (Pro-Strike as Reference Category)

Notes: The plotted values are unstandardized coefficient estimates from the ordered logistic regression model. The treatment effects represent the estimated effects of movement from the pro-strike condition to the other treatment conditions. Bars around point estimates represent 95% confidence intervals. N = 961.

While the results in figures 1–4 are presented without control variables, we demonstrate the robustness of our conclusions with control variables and weights in tables A1 and A2 in the online appendix. An important caveat regarding our experimental research design is that the findings could be influenced by different attitudes in the state of Tamaulipas, potentially inducing pretreatment bias due to respondents’ exposure to the strike. In appendix table A3, we present our results excluding respondents from the state of Tamaulipas from our regression analyses (models 1 and 3 are presented with control as the reference category, while models 2 and 4 use pro-strike as the reference category). Our results remain consistent. In appendix table A4, we also display a simple summary of means by treatment conditions for our outcome variables to illustrate the substantive significance of our findings.

Discussion

What do these results reveal about attitudes toward labor unions and strikes? The findings diverge somewhat from our theoretical expectations, where we predicted that both our treatments would have a significant effect (in a positive direction for the pro-strike messages and a negative direction for anti-strike messages) on support for strikes and the influence of unions, but also where we predicted the treatment effect would be stronger in the case of support for strikes.

Instead, we found that the magnitude of these framing effects varies between the two outcomes, but in ways different from our initial expectations. What explains the finding that an anti-strike frame tends to reduce support for unions more broadly, while a grievance frame increases support for the ongoing teacher strike?

While we initially expected that the outcome support for union influence would be less affected by our treatments, we found that the political opportunism treatment shifted attitudes in a negative direction. This is surprising, given that literature on framing suggests that in domains where people have strongly held beliefs, framing effects have less influence (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2010; Druckman and Leeper Reference Druckman and Leeper2012). We think that our treatment may operate as a “priming device” that activates negative preconceptions and distrust regarding unions, beliefs that are already prevalent in public opinion. As public opinion data in Mexico has shown, a plurality of Mexicans believe that the main beneficiaries of labor actions are the union leaders (COP UVM 2019) and a majority tend to distrust unions (Barnes, Kerevel, and Saxton Reference Barnes, Kerevel and Saxton2023; Latinobarómetro 2023). It seems likely to us that our anti-strike treatment merely raises the salience of these perceptions in the minds of respondents. In other words, we argue that negative sentiments are further amplified by our negative framing treatment, given the strength of these sentiments.

Our results are more in concordance with framing theory in the context of the second outcome: support for striking teachers. When informed about teacher grievances, this message holds relevance for the public, fostering support for the particular strike to address those grievances. Even in contexts like Mexico where preexisting attitudes toward unions are negative, providing citizens with information about grievances associated with strikes increases support for strikers—a goal that unions seek to achieve. This finding suggests that unions might gain more leverage in negotiations during strikes by raising the salience of problems in the workplace that affect workers.

We propose the following mechanism to explain this result: when respondents are reminded of valid justifications for strikes, they develop sympathy for the causes of the strikers, thereby elevating the legitimacy of their actions. However, this also suggests that the effects of a positive framing of strikes are more limited, having impact only on the narrow domain of the current strike, without spilling over to shift views on the broader labor movement. Information on labor grievances does not alter preexisting sentiments toward labor unions, which in Mexico are more negative. Yet, somewhat surprisingly, the negative framing is not able to shift attitudes during ongoing strikes. We interpret this as evidence that citizens think differently about strikes and unions, and that negative sentiments primed by the political opportunism of union leaders do not carry over to respondents’ attitudes toward strikes.

Lastly, the point on the more limited scope of the influence of the labor grievances message compared to union political opportunism aligns well with our finding that when framings are presented in a competitive context—where respondents are exposed to both pro- and anti-strike messages simultaneously (double framing)—the negative message dominates over the labor grievances message for both outcomes. The result highlights the importance of examining pro- and anti-strike messages in competitive environments in other contexts where preexisting attitudes toward unions may differ.

External Validity and Scope Conditions

To what extent do these conclusions generalize beyond the Mexican context? Our findings are suggestive of the conditions under which different messages are likely to have greater power in shaping public opinion. However, we recognize that the generalizability of pro-strike and anti-strike framings depends on country-specific institutions and preexisting attitudes and sentiments toward teachers’ unions and the labor movement more broadly.

First, we believe the effects of pro-strike treatments resonate widely across the developing world and in many industrialized countries, given that grievances like unpaid wages, payroll irregularities, and low salaries are common causes of strikes. Late salary payments and payroll mismanagement, which frequently affect public sector workers, are major issues in many low- and middle-income countries (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, Winthrop, Golden and Ndaruhutse2012). Such grievances signal that unions are engaged in rightful resistance by exposing governmental mismanagement and noncompliance with labor agreements. We would expect that union messages highlighting labor grievances may resonate even more strongly in other Latin American countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Chile, where teacher salaries are relatively low, payroll issues are widespread, and unions are less stigmatized for political opportunism compared to Mexico. Similarly, this framing applies to contexts like the US education workers’ strikes in 2018–19, where salary grievances were the primary driver of teacher mobilizations and where teachers highlighted the problems associated with low pay (Blanc Reference Blanc2019).

By contrast, our findings about political opportunism are only relevant in contexts where labor bossism is a salient issue and union leaders routinely are involved in electoral mobilization and patronage politics. In countries like Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and South Africa, where unions operate as “machine unions,” citizens often have preexisting expectations of political opportunism by union leaders, and this frame is likely to resonate (Schneider Reference Schneider2024). However, we would expect the negative framing of union political opportunism to resonate little or not at all in contexts where unions are more apolitical, or even in cases where unions are involved in politics, but union leaders are not involved in patronage politics. Given the variation in the organizational structure, demands, and patterns of mobilization by teachers’ unions throughout Latin America, we would expect these frames to resonate differently, depending on how salient issues of labor grievances and political opportunism are in those contexts (Chambers-Ju Reference Chambers-Ju2024).

Conclusion

Labor strikes are major disruptive events, and there has been an uptick in labor activity in recent years in Mexico, as well as in many other countries, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Strikes have been an ongoing feature of politics throughout Latin America, and they have the potential to dramatically shift public opinion—either in favor of workers or against them. However, while considerable research has explored the economic effects of labor strikes and the ways union affiliation shapes the attitudes of union members, there is little work on how strikes affect public opinion. We employ an original survey experiment to analyze how pro- and anti-strike framings influence public support for unions and striking workers. To our knowledge, our paper is the first application of experimental methods to the study of strike frames on public attitudes outside the US. Our finding is that the political effects of labor actions are shaped by how the motives for strikes are framed.

Our research has implications for labor politics and framing effects. First, public attitudes toward unions and strikes are often conflated in the literature. Our results suggest that different underlying causal processes explain changes of opinion toward each of them. Our first contribution highlights how messaging by both unions and their opponents (i.e., employers) may be effective in shaping public opinion, albeit in different ways.

Regarding framing effects on support for unions during strikes, our findings align with previous literature that highlights the impact of negative frames used by union opponents in diminishing public support for the union movement (Kane and Newman Reference Kane and Newman2019). We place positive and negative frames in a competitive context, demonstrating that negative frames have a slightly stronger resonance than positive ones. During political debates surrounding strikes, it is more challenging to improve the image of unions than it is to damage it, reinforcing the idea that negative campaigning is an effective strategy—a notion we extend to unions. We suggest that this occurs because information about labor grievances during strikes fails to overcome preexisting negative sentiments toward unions. An implication of our results is that the communication departments of unions face an uphill battle to change deeply rooted negative attitudes toward labor unions, at least in contexts where unions have been stigmatized by patronage politics.

Existing literature, particularly in the US context, suggests that anti-labor narratives often dominate media coverage (Harmon and Lee Reference Harmon and Lee2010; Park and Wright Reference Park and Wright2007; see Valdés Vega [Reference Valdés Vega2020] for a comparative perspective from the Mexican context). Our findings indicate that the strength of the labor movement is limited not only quantitatively—by getting attention in the media—but also qualitatively: union messages have less impact in competitive contexts, such as those found in the media.

Public opinion regarding specific strikes, by contrast, may be influenced differently by framings compared to their influence on attitudes toward unions. Our results suggest that although union messages may not significantly influence broad support for the labor movement, they can enhance the legitimacy of specific strikes. Despite common underlying causes, each strike may be perceived as distinct by outsiders and may shift public beliefs regarding real grievances, even in areas where strikes are frequent. By identifying and promoting messages about strikes that resonate with the public, unions can still cultivate support for their mobilizations by effectively communicating the reasons behind their actions (Clark Reference Clark2010). Union media strategies might help to explain how teacher strike waves to pressure governments to improve salaries and block new education laws (which some experts argue could enhance teacher quality) are often successful (Bruns and Luque Reference Bruns and Luque2014, 304–7; Schneider Reference Schneider2024).

Future research should explore pro- and anti-labor framings in contexts outside Mexico, particularly in places where historical factors have created higher levels of trust and support for unions. We acknowledge that the impact of these frames is influenced by how often they appear in the media. A limitation of our study is that we did not measure the actual prevalence of pro- and anti-labor messages during strikes, as our experimental design relied on constructed vignettes rather than observational media and newspaper data. Ultimately, the effectiveness of these messages depends on how well unions and their opponents can promote their narratives in the media (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007). Nonetheless, we believe that our experimental approach has significant potential for understanding the effects of unions and labor mobilization on public opinion outside the US context.

Moreover, our contributions align with the literature on framing effects in public messaging (Benford and Snow Reference Benford and Snow2000; Bonilla and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020). The way strikes are framed through messaging shapes how they are interpreted by mass publics. While earlier research suggests that framing effects have less influence in areas where beliefs are strongly held—like in the case of unions (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2010)—we find that our anti-strike treatment “activates” strong preexisting opinions. Therefore, the framework of framing effects should consider how varying strengths of prior attitudes can affect responses to public messages.

We propose several avenues for future research to further explore the effects of strike frames on public opinion. First, the effects of pro- and anti-strike framings documented in this study may differ across subgroups. While our analysis could not address these differences due to insufficient power in subgroup comparisons, Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu, and Reich (Reference Hertel-Fernandez, Naidu and Reich2021) suggest that parents of school-age children in public schools are particularly affected by teacher strikes. Their close contact with public school teachers may foster greater sympathy for the teachers’ grievances. Additionally, subgroup differences may exist based on gender, income, education, and partisanship.

Second, future research should examine a broader array of anti- and pro-strike treatments, extending beyond the themes of salary grievances and the political ambitions of union leaders. For instance, studies could differentiate between various types of labor grievances, such as claims for back pay versus concerns regarding low wages (even if those wages are paid on time). Moreover, teachers articulating broad-based demands that benefit students—such as reductions in class size, funding for new textbooks, or resources for school nurses and librarians—are likely to engender greater sympathy and support compared to narrower demands focusing solely on low pay or other labor issues.

Third, future work should explore additional outcome variables beyond public support for unions and strikes. This includes respondents’ personal interests in labor action and their willingness to sign petitions in favor of strikers. Examining these factors would enhance our understanding of how strike framings engender deeper commitments to workers.

Fourth, investigations into framing effects could consider the source of information. While our study has focused on the framing effects of messages prevalent in the media, future studies could investigate more direct exposure through experimental and quasi-experimental designs. For example, firsthand exposure resulting from traffic disruptions or direct observation of labor demonstrations may have differing impacts. A video featuring a personal appeal from a teacher might resonate more strongly than a union leader reciting a list of demands from a union communiqué. While our findings regarding pro- and anti-strike framings in competitive context yield intriguing conclusions, further research should examine these issues in comparative perspective, looking closely at contexts where societal attitudes toward labor unions are generally unsympathetic, and comparing them to contexts where attitudes are more sympathetic.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592725000660.

Data replication

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/W2TSVL

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following for providing invaluable assistance in developing this project: Radha Sarkar, Andres Sandoval, Laura Stoker, Julia Coyoli, Leslie Finger, Kayla Canelo, Roman Hlatky, Brian Palmer-Rubin, Alejandro Díaz Domínguez, and Susan Stokes. We also thank participants at the Texas Comparative Circle, the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, the Annual Political Science Conference at Tecnologico de Monterrey, and the faculty research seminar at the same institution. This survey was preregistered with the Open Science Framework as “The Moral Economy of Education Reform in Mexico” on October 25, 2023 (https://osf.io/azut2). Mistakes are our own.