Introduction

Gig work, which was originally used to refer to the hiring of musicians to perform on a per-show basis, is now being used to refer to independent work (i.e. no employer–employee relationship) done through online platforms (Alfes et al Reference Alfes, Avgoustaki, Beauregard, Cañibano and Muratbekova-Tourom2022; Chalermpong et al Reference Chalermpong, Kato, Thaithatkul, Ratanawaraha, Fillone, Nguyen and Jittrapirom2023; Shen, Reference Shen2020; Woodcock & Graham Reference Woodcock and Graham2020). Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, gig work was burgeoning in developed and developing economies (Conen & Stein Reference Conen and Stein2021; Dreyfuss Reference Dreyfuss2020; Kalleberg Reference Kalleberg2009; Vyas & Butakhieo 2020). The emergence of gig work has disrupted the labour market and challenged the traditional work setup of employees working in workplaces from Monday to Friday, 9 am to 5 pm, and having job security and company loyalty (Bolino et al Reference Bolino, Kelemen and Matthews2020; De Vos & Van der Heijden Reference De Vos and Van der Heijden2017; Zwettler et al Reference Zwettler, Straub and Spurk2023).

However, the experience of developed countries shows that there are challenges related to the rise of gig work. For example, American gig workers face uncertainty and unpredictability in stable employment availability and income generation (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020; Kalleberg & Dunn Reference Kalleberg and Dunn2016; Rosenblat & Stark Reference Rosenblat and Stark2016). Experiences from Europe and Japan reveals how gig workers may have to work considerable overtime and be on-call for their clients. Coupled with stressful circumstances such as the pandemic, such demands can lead to mental health decline (Broughton et al 2019; Tomono et al Reference Tomono, Yamauchi, Suka and Yanagisawa2021; Warren Reference Warren2021). There is also a gender aspect to these challenges. Women, who often carry the burden more in terms of child-rearing, do gig work that fits into their home care schedules (Churchill & Craig Reference Churchill and Craig2019; Powell & Craig Reference Powell and Craig2015). In all such situations, gig workers are often not entitled to regular benefits and welfare protections such as minimum wage and social security benefits that traditional employees have received (Ro Reference Ro2022).

Nevertheless, gig work can also be a potential path towards economic development, especially for developing countries. These gig work jobs that were non-existent before the advent of the internet have become potential additional income streams for gig workers located in developing economies (Anderson et al Reference Anderson, McClain, Faverio and Gelles-Watnick2021; Ng’weno & Porteous Reference Ng’weno and Porteous2018; Rothwell Reference Rothwell2019). Still, there remain gaps in the literature as only a few studies have been done covering gig workers in developing economies. These studies mainly cover African countries with considerably different socio-economic contexts. Indeed, they differ greatly from the Philippines, which is considered a major hub for outsourcing (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020; Graham et al Reference Graham, Hjorth and Lehdonvirta2017; Lehdonvirta et al Reference Lehdonvirta, Rani, Kässi, Furrer, Stephany and Gobel2024; Lesala Khethisa et al Reference Lesala Khethisa, Tsibolane, Van Belle, Bandi, Ranjini, Klein, Madon and Monteiro2020; Rani & Furrer Reference Rani and Furrer2020; Ray & Thomas Reference Ray and Thomas2019). The few studies that do cover gig work in the Philippines have been more focused on the policy and regulatory environment (Serafica & Oren Reference Serafica and Oren2022; Tacadao et al Reference Tacadao, Navarosa, Bondad and Sto Tomas2023).

Given these contexts, this exploratory study seeks to answer the question of what are the motivations behind individuals’ transition to gig work. What have been the outcomes and challenges, especially in the context of pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19? As such, the research has aimed to give a snapshot of the labour market in the Philippines in light of the increasing significance of gig work.

To explore these questions, we conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with those working as purely online gig workers, and also with those working as location-dependent gig workers in the Philippines. Thematic analysis was employed to analyse data from FGDs. The initial codes were generated from English translations of the interviews and were then grouped into themes.

The study revealed that while gig workers appreciated the flexibility of managing their own time, they also expressed a need for increased government support and regulation to ensure their welfare is protected. Given that certain drawbacks have emerged over time in relation to gig work in the Philippines, and as technology rapidly evolves, it is important that the government and platforms provide measures to safeguard the well-being of these workers.

Review of related literature

Literature varies on how to classify gig work. Vallas and Schor (Reference Vallas and Schor2020), for example, classified gig work into two types, namely: (1) those engaged in ‘taxi, courier, and cleaning services’, and (2) ‘tradespersons, performing artists, and caregivers’. Vallas and Schor (Reference Vallas and Schor2020) noted that these jobs involved people hiring gig workers through platforms and applications designed to provide services such as ride-hailing and food delivery. Similarly, Alvarez de la Vega et al (Reference Alvarez de la Vega, Rooksby and Cecchinato2020) classified gig work into, ‘location-dependent gig work’ and ‘online gig work’, with the former involving food delivery and ride-hailing via platforms such as Uber and Deliveroo, while the latter refers to those with IT skills who work from homes on software development and web development.

The COVID-19 pandemic and gig work

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a boom in location-dependent gig work given that food delivery became an important component of the platform’s business operations during the lockdowns (Dreyfuss Reference Dreyfuss2020). However, the lack of benefits for gig workers was challenging for gig workers during disasters or public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Morshed et al Reference Morshed, Khan, Tanvir and Nur2021). Among those who were hardest hit during the COVID-19 pandemic were those working in the ‘sharing economy’, which included location-dependent gig workers – drivers for the said apps such as Grab and Uber saw their incomes decline due to the lack of customers (Chan Reference Chan2020; Hossain Reference Hossain2021). Delivery riders were also vulnerable to COVID-19 when ferrying passengers, parcels, and food (Alvarez de la Vega et al Reference Alvarez de la Vega, Rooksby and Cecchinato2020). Given their status as ‘contractors’ instead of employees, they rarely had access to benefits such as private health insurance in times of need (Hossain Reference Hossain2021).

Motivations to joining gig work

Research has shown that traditional or ‘9-to-5’ workers rarely consider leaving traditional jobs for gig work (Alfes et al Reference Alfes, Avgoustaki, Beauregard, Cañibano and Muratbekova-Tourom2022; Chalermpong et al Reference Chalermpong, Kato, Thaithatkul, Ratanawaraha, Fillone, Nguyen and Jittrapirom2023; Shen Reference Shen2020). Rather, the motivations for becoming gig workers can be classified into two types: opportunity-driven and necessity-driven. Those who are opportunity-driven are motivated by new and fruitful chances, while those who are necessity-driven have limited or no options in the job market (Fairlie & Fossen Reference Fairlie and Fossen2018; Reynolds et al Reference Reynolds, Camp, Bygrave, Autio and Hay2001). Those with opportunity-driven motivation see gig work as a side job instead of the main job, especially among those in the developed world. Anderson et al (Reference Anderson, McClain, Faverio and Gelles-Watnick2021) found that about 30% of gig workers in the United States treat their gig work as a side job whereas, for other opportunity-driven workers, gig work allows them to be their own boss with complete control of their time (Jacobs Reference Jacobs2017).

On the other hand, necessity-driven motivation is found where there is a lack of available regular jobs, especially in developing countries (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2017). For example, in developing countries such as Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa, the lack of available jobs, together with the relatively easy ‘onboarding’ process wherein one can quickly sign up and work for these digital platforms, motivates workers to pursue gig work. (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2017). This means that these gig jobs are the workers’ main jobs (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020).

Experiences of gig workers in the developed world

Gig work can increase the work-life balance of some workers, given that some are their own bosses and manage their own schedules. For example, London Uber drivers reckon that their well-being has improved, especially those who highly value flexible work arrangements (Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019). Further, some of these drivers have received higher income, especially those who had come from traditional blue-collar work (Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019). Their flexible schedules also enable these workers to take on multiple projects and work, allowing them to increase their incomes further (Sarker et al Reference Sarker, Taj, Sarkar, Hassan, McKenzie, Al Mamun, Sarker and Bhandari2024).

On the other hand, gig work also offers problems and challenges for workers. American gig workers working for companies such as Amazon and Uber are controlled through algorithms on which digital platforms depend, causing uncertainty and unpredictability in employment availability and work tasks. By contrast, in conventional gig work, individuals have more direct influence over finding employment and negotiating tasks (Kalleberg & Dunn Reference Kalleberg and Dunn2016; Rosenblat & Stark Reference Rosenblat and Stark2016). Moreover, platforms often retain a fee on each transaction, which limits the net earnings of gig workers (Rosenblat & Stark Reference Rosenblat and Stark2016). In essence, the use of platforms rather than directly dealing with clients fundamentally alters the nature of the worker–client relationship. It also highlights the trade-off between convenience and lack of autonomy. For example, many gig workers are obliged to agree (or refuse) the platform’s changing terms and conditions; a negative answer may lead to a worker being penalised or receiving low ratings for refusing task requests and other similar situations (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020; Kalleberg & Dunn Reference Kalleberg and Dunn2016).

Even purely online gig workers may experience demands for unwanted overtime. For instance, European gig workers, who often have minimal social safety nets, may have to render overtime services or be on call to satisfy client demand (Broughton et al Reference Broughton, Green, Rickard, Swift, Eichhorst, Tobsch, Magda, Lewandowski, Keister, Jonaviciene, Martín Ne, Valsamis and Tros2016; Warren Reference Warren2021). In turn, increased overtime may lead to deteriorating mental health. This was especially the case in Japan, where a huge swath of respondents saw declining mental health due to increased overtime and social isolation after the beginning of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of quarantine measures (Tomono et al Reference Tomono, Yamauchi, Suka and Yanagisawa2021).

There are also gender differences in terms of the types of work gig workers do. Churchill and Craig (Reference Churchill and Craig2019) found that male gig workers in Australia used delivery and ridesharing applications such as Uber and Deliveroo while female gig workers use platforms such as Freelancer that involve more online work such as clerical, graphic design, and digital marketing. This gender difference, nevertheless, may put extra pressure on women gig workers as may have to juggle their household chores and work responsibilities. Powell and Craig (Reference Powell and Craig2015) found that women working from home regularly (i.e. those who work at least 50% of full-time work hours) spend about 60 minutes per day more on childcare than those who do not work from home. Women also tend to choose jobs that fit into their schedules that are already filled out with childrearing duties (Churchill & Craig Reference Churchill and Craig2019).

Lastly, there is an issue of social protection for gig workers. As far back as 2015, U.S. presidential candidates talked about the ‘Uberization’ of the economy, wherein workers are tagged as ‘independent contractors’ by platforms such as Uber and Lyft, and so do not receive employee benefits (Morshed et al Reference Morshed, Khan, Tanvir and Nur2021; Powell Reference Powell2015). There are also the issues of unpredictable cash flow and work hours and the ‘outsourcing’ of overhead costs from the company to the worker, such as those experienced by Uber drivers (Stanford Reference Stanford2017). These challenges become more apparent during disasters or public health crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Morshed et al Reference Morshed, Khan, Tanvir and Nur2021). Among those who were hardest hit during the COVID-19 pandemic were those working in the ‘sharing economy’. Moreover, as ‘contractors’ instead of ‘employees’, gig workers often do not have access to benefits such as private health insurance and family leave for times of need (Hossain Reference Hossain2021; Matherne & O’Toole Reference Matherne and O’Toole2017).

Opportunities of gig work for developing economies, including the Philippines

Despite these challenges, including those experienced in developed countries, gig work can be a path towards economic development, especially for developing countries. Lehdonvirta et al (Reference Lehdonvirta, Rani, Kässi, Furrer, Stephany and Gobel2024) found that India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan are the top three countries where online work is conducted. Indeed, approximately half of all online work worldwide is being undertaken in these three countries.

Moreover, while gig work is considered less valuable than traditional work, gig work is more abundant in developing countries and more accessible to more people regardless of their educational attainment (Ng’weno and Porteous Reference Ng’weno and Porteous2018). In these developing countries, the relatively easy ‘onboarding’ process of the digital platforms allows gig workers to sign up and work for them quickly (Anwar & Graham Reference Anwar and Graham2020; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2017). These platforms also create jobs that were non-existent before the advent of the internet and offer more potential income streams for gig workers (Anderson et al Reference Anderson, McClain, Faverio and Gelles-Watnick2021; Ng’weno & Porteous Reference Ng’weno and Porteous2018; Rothwell Reference Rothwell2019).

Certainly, gig work has become an important part of the labour market and economy of the Philippines. The Philippines has been a global hub in terms of outsourcing, with the internet further allowing Filipinos to access online jobs (Ray & Thomas Reference Ray and Thomas2019). In 2024, the Philippines is ranked 9th and provided 1.8% of online work globally (Lehdonvirta et al Reference Lehdonvirta, Rani, Kässi, Furrer, Stephany and Gobel2024).

On the other hand, there is a lack of appropriate regulatory frameworks for gig workers, especially in developing countries such as the Philippines. For example, the current Labor Code of the Philippines was promulgated during the 1970s, during which time the Philippine government focused on an import-substitution economic policy. The government also sought to enable workers to become regular employees with benefits such as minimum wages, overtime pay, and security of tenure (Macaraya Reference Macaraya2006). In these times, however, gig workers in the Philippines receive few of the benefits that traditional workers get (Graham et al Reference Graham, Hjorth and Lehdonvirta2017). Furthermore, as well as a lack of employee benefits, gig workers must also deal with the bureaucratic hassles and contradictory rules in terms of registering and paying taxes (Serafica & Oren Reference Serafica and Oren2022).

This is also compounded by the paucity of reliable data on the gig economy, including the actual number of gig workers (Tacadao et al Reference Tacadao, Navarosa, Bondad and Sto Tomas2023). While there are no exact figures, it was estimated in 2021 that around 1.3 million to 1.5 million Filipinos were considered online gig workers, specifically those working in the creative industry (Mercado 2021, as cited by Piad Reference Piad2021). Similarly, Esquivias et al (Reference Esquivias, Guillen, De Costo, Viernes, Aquino and Embile2022) estimated there were 1.69 million online gig workers. As well, there were about 400,000 location-dependent gig workers, according to Fairwork (2022). In another report, this time from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2023), more than half of delivery riders working for the application Grab started working as delivery riders after the onset of the pandemic. Overall, the lack of awareness appears to have prevented the government from addressing concerns about gig work as it has no idea of the extent of the contribution of gig workers to the economy and of how to provide targeted employment protections for these workers.

Theoretical framework

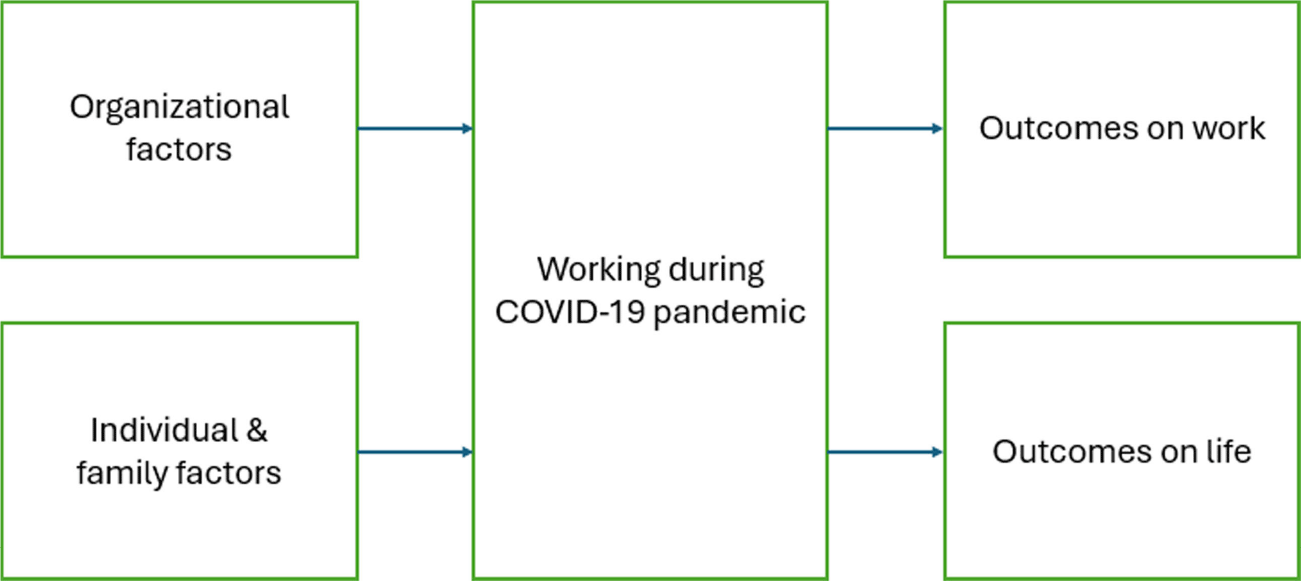

This study relies on the framework adapted from Vyas and Butakhieo (2020) (Figure 1). While the original framework only covers those who are working from home (i.e. purely online gig workers in this study), the revised framework for this study will also cover the location-dependent gig workers.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework; Source: Revised framework adapted from Vyas and Butakhieo (2020) Instruction.

Under this framework, a gig worker working during COVID-19 is affected by both organisational factors, and individual and family factors. The former factors are related to work-related experiences such as working relations with managers and colleagues, flexible work schedules, and costs related to doing gig work (Dizaho et al Reference Dizaho, Salleh and Abdullah2017; Jabagi et al Reference Jabagi, Croteau, Audebrand and Marsan2019; Purwanto et al Reference Purwanto, Asbari, Fahlevi, Mufid, Agistiawati, Cahyono and Suryani2020). As mentioned earlier, gig work allows workers to be their own bosses, so they can take on as many projects as possible (Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019; Sarker et al Reference Sarker, Taj, Sarkar, Hassan, McKenzie, Al Mamun, Sarker and Bhandari2024). Nevertheless, gig workers working from home may have to absorb some of the costs related to doing gig work such as electricity and internet costs (Purwanto et al Reference Purwanto, Asbari, Fahlevi, Mufid, Agistiawati, Cahyono and Suryani2020). The latter factors are related to the gig worker’s personal life such as the ability to do lightly supervised work, motivation for choosing gig work, and the presence of elderly and children in care at home (Baruch Reference Baruch2000; Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019; Churchill & Craig Reference Churchill and Craig2019; Kazekami Reference Kazekami2019). For example, parents, especially mothers, arrange gig work that is amenable to their childrearing schedules (Churchill & Craig Reference Churchill and Craig2019).

We also aim to examine how working during COVID-19, in turn, affected both the work outcomes and life outcomes of these workers. The former set of outcomes is related to matters such as income, work performance, and productivity (Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019; Kazekami Reference Kazekami2019; Sarker et al Reference Sarker, Taj, Sarkar, Hassan, McKenzie, Al Mamun, Sarker and Bhandari2024). For instance, gig work has the potential to deliver higher incomes to those who choose to shift careers from their old jobs (Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019). Moreover, gig work has the potential to increase labour productivity for those working remotely (Kazekami Reference Kazekami2019). The latter set of outcomes, on the other hand, is related to issues such as work-life balance and life satisfaction (Berger et al Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019; Dizaho et al Reference Dizaho, Salleh and Abdullah2017). For example, the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic shows that working from home increases free time and lessens stress for these workers as they do not have to contend with traffic jams and other issues related to on-site work (Purwanto et al Reference Purwanto, Asbari, Fahlevi, Mufid, Agistiawati, Cahyono and Suryani2020)

Data and methods

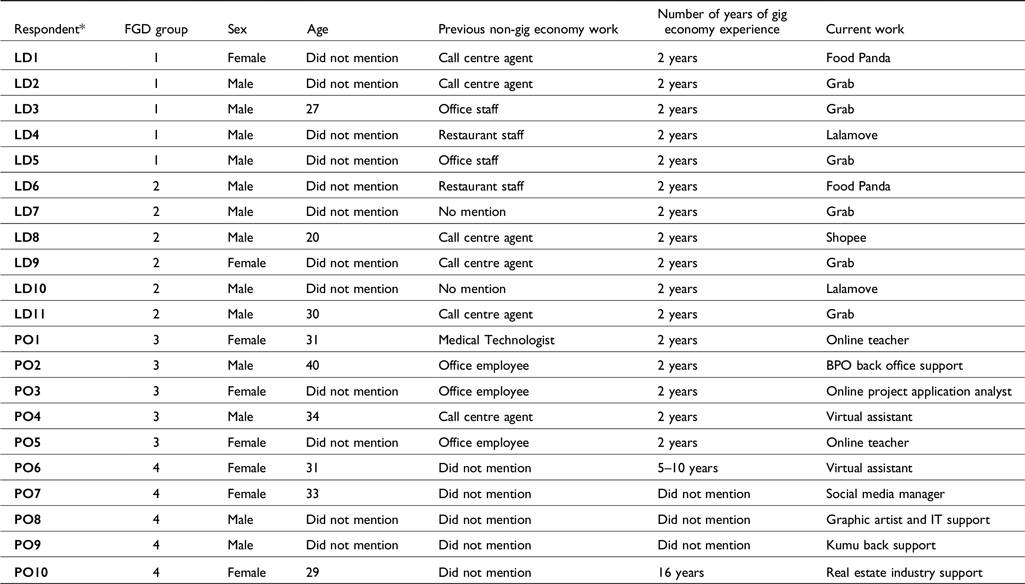

In this paper, we conducted FGDs in the first week of April 2022 to explore the experience of those working in the gig economy in the Philippines. Four groups were interviewed for this study. Two of these groups (i.e. FGD groups 1 and 2) were those working in location-dependent gig work, which includes food delivery riders of applications such as Grab and Foodpanda. The other two groups (i.e. FGD groups 3 and 4) are classified as purely online gig workers who can work anywhere. Conducting two FGDs per type of gig work is in line with the study of Guest et al (Reference Guest, Namey and McKenna2017), which states two to three FGDs are enough to get more than 80% of the information needed.

There were five members per group, which is in line with the recommendations of Dzino-Silajdzic (Reference Dzino-Silajdzic2018), Muijeen et al (Reference Muijeen, Kongvattananon and Somprasert2019), and Stalmeijer et al (Reference Stalmeijer, McNaughton and Van Mook2014). The exception is with FGD group 2, which had six members but one respondent, namely LD10 got disconnected completely from the FGD due to weak internet connection. Instead, he was replaced by LD11.

The two gig worker classifications (i.e. location-dependent gig workers and purely online gig workers) were adapted from the ‘location-dependent gig work’ and ‘online gig work’ classifications done by Alvarez de la Vega et al (Reference Alvarez de la Vega, Rooksby and Cecchinato2020) – the location-dependent gig workers are those that do food delivery and ride-hailing via platforms such as Grab and Lalamove while the purely-online gig workers are those who do work from their homes and have no fixed office spaces such as software developer and web developers.

For location-dependent gig workers, the selected respondents include those who used to work at traditional or 9-to-5 jobs but then moved to do location-dependent work due to job layoffs from their previous jobs or due to their hours being cut in their previous jobs. This selection was because food delivery services boomed during the COVID-19 lockdowns given that food delivery became an important component of the platform’s business operations during these instances (Dreyfuss Reference Dreyfuss2020; Katiyatiya & Lubisi Reference Katiyatiya and Lubisi2024).

The selected respondents for the purely-online gig workers were a mix of those who previously worked at traditional or 9-to-5 jobs but then shifted to doing gig work due to job layoffs from their previous jobs, and those who never worked in a traditional or 9-to-5 job. The inclusion of those who never worked in the formal economy is because non-traditional or non-9-to-5 jobs always existed, even before the COVID-19 pandemic (Conen & Stein Reference Conen and Stein2021; Kalleberg Reference Kalleberg2009).

A third-party data-gathering firm recruited the participants based on the abovementioned criteria and asked the participants demographic questions such as sex and age as part of its pre-screening process. The authors decided to tap the services of this data-gathering firm given that it has the expertise of getting easily the needed respondents; this expertise did prove useful especially in the context of the COVID-19 quarantine restrictions across the Philippines during that time. The same firm also conducted the FGDs in Filipino, transcribed the FGDs, and translated the FGD transcriptions into English. Each FGD lasted for about one hour to an hour and thirty minutes. The survey firm informed the participants that the FGDs were recorded, and their participation was voluntary and could be withheld by them anytime. The firm also assured the participants of their anonymity and data privacy following, among others, the Data Privacy Act of 2012. To ensure confidentiality of the respondents’ identities, the names of the respondents working in location-dependent gig work were replaced by ‘LDn’, with ‘n’ being a number from one (1) to eleven (11). The names of the respondents working in purely online gig works were replaced with ‘POn’, with ‘n’ being a number from one (1) to ten (10).

FGDs enabled respondents to interact with each other about their respective experiences, enriching the discussion further. This interaction also allowed us to unearth relevant responses in the discussion even if they were not asked for in the guide questions (International Bank for Reconstitution and Development/The World Bank, 2020). Given the uncertain conditions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of the interview, the team conducted the FGDs via the Zoom teleconferencing application.

One of the co-authors (CA1) performed the thematic analysis following the steps provided in Braun & Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). First, CA1 generated initial codes from the verbatim transcriptions and English translations of the FGDs that the third-party data-gathering firm did. CA1 then grouped the different initial codes into similar themes and named the different themes. After the searching of the themes, the other co-author (CA2) reviewed and validated the themes and their respective names, and the initial codes that CA1 did. The two co-authors then sat down for a series of meetings to finalise the themes and their respective codes before writing the results of the paper.

The profile of the FGD respondents is in Table 1.

Table 1. Profile of respondents

*LD = location-dependent gig workers; PO = purely online gig workers.

Results and discussion

This section discusses the five themes that were uncovered during the FGDs. The first theme was ‘motivation behind shifting or doing gig work’, which discusses the reasons for moving to or doing gig work. The second theme was ‘preparing for gig work’, which discusses their preparations for working in the gig economy. The third theme, ‘experiences in and sentiments on gig work’, talks about their positive and negative experiences once they became part of the gig economy. The fourth theme, ‘aspirations and long-term objectives’, explores the respondents’ aspirations and long-term goals for themselves, their families, and others. Lastly, the fifth theme, ‘support needed’, was about the support measures they received and wished to receive from the platforms they work with and the government.

Using the framework shown earlier, the first theme falls under the individual and family factors, the second theme falls under the organisational factors, and the third, fourth, and fifth themes fall under outcomes on work and life.

Results

Motivations behind shifting to or doing gig work

The respondents’ motivations for doing or shifting to gig work can indeed be classified into two: opportunity-driven and necessity-driven.

For purely online gig workers such as PO6 and PO7, both of whom started working even before the pandemic, their shift was more opportunity-driven, because they see this work as a more convenient way of earning higher incomes instead of dealing with traffic. This, in turn, meant they could attend more quickly to their family responsibilities and save more money quickly.

I really planned to work from home since 2008 when I was still in the BPO in Manila. I was not able to save money because I was renting a house and I was alone because my parents are here in the province. So that was my way of being a VA so that I can go back here in the province because honestly, it is cost-efficient, you don’t need to pay different things, things like rent. So my life became better here in the province. I was able to save at the same time, not just the needs but also the wants. That is why. (PO6)

[My motivation was] the convenience because [of the] traffic before. It was hard to go to work pre-pandemic time, and I was also needed at home. My grandma needed me to take care of her. So, I looked for work from home. (PO7)

Nevertheless, one location-dependent gig worker already owned a motorcycle and saw the pandemic as an opportunity to apply as a rider, as was the case of LD9.

The motorcycle was from my previous job … [inaudible]. It’s a manufacturer of [inaudible]. It closed when the pandemic started, so I transferred to Grab. (LD9)

On the other hand, purely online gig workers who started working as such during the pandemic (i.e. PO2, PO3, PO4, PO5), their shift can be considered necessity-driven as they shifted to gig work because they were retrenched.

So there, one of my struggles is the company stopped, it closed down. All of us lost our jobs last April 2020 also and then luckily I was able to find an online job through Upwork, so this is it. I’m still working luckily so far this is what keeps us alive. (PO3)

So before I worked as a graphic artist in a company in Makati. We were catering and distributing Japanese products. So I’m the one handling their marketing collaterals when it comes to tarpaulin, brochures and everything, web designs sometimes. And then the pandemic happened, it was difficult to go out of the house so you are not safe anymore, it’s like you are hesitant to work because you have kids also…So what happened was we were laid off [by the company], so almost everybody and eventually during the month of April 2020, the company closed down because of how long it was because we also had branches in malls so they were not able to open, no revenue. And then I was saddened because I am not used to not having work… [Then,] as I was scrolling my Facebook feed, I saw the ad of 51Talk and then as long as you are a college grad, they will hire you, something like that even though you have not graduated as a teacher and then I tried it and then I said, oh my, I think my age does not fit but the good thing about 51 is there is no age limit as long as you can teach. (PO5)

This is also the case for location-dependent gig workers – five of them (i.e. LD2, LD3, LD4, LD5, and LD11) voluntarily resigned from their previous traditional work as they saw their working hours getting cut while one (i.e. LD1) was retrenched. Given that they lost their jobs or saw their hours getting cut, these respondents see the need to shift to gig work to get by during the height of pandemic-related quarantine measures.

Before the pandemic, I was a call centre agent but I was one of the people who was removed, maybe it was because I was not yet a regular employee. I didn’t pass the work from home. That is why when the pandemic started, since I needed to earn money, my friend encouraged me to become a lady rider in Food Panda. It was a good thing that I passed it that is why I am a rider now of Food Panda. (LD1)

I was a cook in a restaurant before. That was my work before the pandemic. It was a bit rough during that time because they laid off some employees and then a long period of time of no work was added because of lack of manpower so I decided to resign because it was a heavy workload. Since I have my own motorcycle, I decided to enrol it in Lalamove. My earning in Lalamove is okay because I handle my time and my time with my family. (LD4)

Preparing for gig work

The location-dependent gig workers mentioned that they invested in items such as motorcycles and bicycles to meet their need to move constantly from one area to another. They also bought items such as helmets, rash guards, insulated bags, raincoat, water jug or tumbler and mobile data expenses.

How they funded this investment differed from one rider to another. LD3 mentioned that he borrowed money from his mother to buy a bicycle. Another rider, LD7, said that he borrowed money to buy his motorcycle and that he is repaying the loan in instalments using his earnings as a rider.

Since it’s really difficult to get transactions nowadays, I had to get a loan so that I can pay for my motorcycle in instalments. It’s difficult to settle things that I need to settle. They have more partners now. I think their priority is the merchants. (LD7)

On the other hand, LD4 mentioned that he saved little by little to buy all the necessary work gear.

I saved up for the helmet little by little. For example, if you’ve earned P1,000, you’ll keep P100 for the helmet, or if you find a rash guard, that first. I got it little by little and not all at the same time. I saved up for it. (LD4)

On the other hand, purely online gig workers invested in reliable and fast internet connectivity and even upgraded their existing internet speeds to ensure continuous connectivity. They also bought laptops and other equipment such as ring lights, uninterruptable power supplies (UPS), and external hard drives for their dedicated workstation at home.

Currently, I availed just recently the Converge (a Philippine-based internet service provider) [subscribing to the] 300 mbps [plan] which is very good. My working is continuous, no interruptions. So that’s it guys, try it out. It is really okay. (PO3)

For me, I bought a Globe prepaid, the broadband that you load. I cannot buy the generator so I purchased a UPS. (PO4)

For the sources of funds for their equipment, PO4 and PO5 mentioned that they used their personal savings. PO8 worked other part-time jobs to be able to buy their work equipment.

I invested in a machine, and at some point, I used to be a Lalamove driver. I worked in the office and at the same time did some Lalamove so that I could acquire a computer… So my machine now is capable of editing videos and all that. (PO8)

In general, the location-dependent gig workers and purely online gig workers made investments in preparation for shifting to gig work depending on what their gig work specifically entails.

Experiences with, and sentiments on gig work

Perceived advantages and benefits of being a gig worker

One advantage that both purely online and location-dependent workers cited, was the flexible and convenient working hours and schedule; they saw this as allowing them to have breaks to attend to family and other personal matters. Specifically, LD4 and LD9 mentioned that with their flexible work schedules, they could help their spouses take care of their younger children.

PO2, PO3, and PO8 said that they did not feel burned out since they could attend to personal errands and manage their own time.

And then the health, actually, since I started my online job, I just stay here inside the house, work from home. So I learned to work out, exercise every morning, things like that. With my family also, more time, more quality time with them especially with my parents because they are old already so that’s it. (PO2)

Overall, this flexible arrangement allows them to have a better work-life balance and enables these gig workers, specifically LD2, LD3, LD4, LD5, PO6, and PO8, to be their bosses and not be micro-managed or monitored by their bosses or even co-workers.

You are able to do a good job for your customer, I mean he will repeat buying his order not only because his order is there but also appreciating a rider who knows how to talk properly with customers, that’s what I consider as a good job. Compared to my previous job, this is better because it’s an individual job unlike before you are being supervised by your boss, even your co-workers monitor you. If you don’t do anything while working and being monitored there’s a possibility of losing your job. With the job now, if you don’t work no earnings, you just have to work hard. (LD3)

Maybe I like my current work. Because I don’t have a boss and I handle my own time. I can do whatever I want. If I want to go home and rest. I can go to trips anytime. Unlike my work before we have a timed shift, you are not allowed to just stand there. You need to move because somebody is watching you. You need to be hardworking, before I have minimum wage, now you just have to work hard and you will earn a lot. I like my work now, unlike before. (LD5)

Another advantage cited by both groups was that their income was also higher than before. LD8 mentioned that while others may belittle their work, it does not matter anymore given their increased income, allowing them to provide for their family. PO8 added that his higher earnings from freelancing work allowed him to buy some luxury items. PO6 and PO10 shared that their clients from overseas sent them gifts and cash bonuses in addition to their regular pay.

Other perceived advantages were career growth, forming bonds among fellow gig workers, and expanding their networks. PO4 said that freelancing expanded his network (albeit virtually) since he was able to get learning opportunities to upskill. Among location-dependent gig workers, whenever they are unfamiliar with a customer’s pinned location or run out of cash, they felt they could easily turn to their fellow riders with whom they have become friends.

Another advantage for them is career growth in terms of career shifts and upskilling. PO5 mentioned that they have regular training as online teachers, which provides them with opportunities to move up their ranking. PO10 said that freelancing gave them the opportunity to explore other types of jobs and expand their skills and knowledge.

When asked about the perceived advantages of using or working for digital platforms, the purely online gig working respondents noted that these platforms are convenient, secure, and easy to use. For PO6 and PO9, while there are costs when using platforms, they still prefer it instead of directly coordinating with their clients given the platform’s security. For PO6 and PO7, they found that it is better to have a platform to mediate between the clients and gig workers to ensure that they will get paid and market themselves efficiently.

[The] benefit is that you are secured that the client will pay you because my aunt had a client in UK before when the MyOutDesk or Odesk was still new. Then it was an HR job, they asked her to make contracts and I think what happened was, they talked outside the platform, so what happened was she was not paid, they ran from her. The things they asked for were hard, HR manager, contracts. So if it is under a platform, the employees are more secured. (PO7)

On the other hand, one advantage for location-dependent gig workers is that work for them is deemed lighter compared with their previous job. There is also no forced overtime to meet the work quota, and they they felt they could explore different places. Moreover, location-dependent gig workers working for platforms such as Lalamove and Foodpanda receive accident and life insurance, as well as incentives whenever they reach a certain number of bookings; these benefits included discounts for some motorcycle parts, free food, drinks, and other stuff such as raincoats, long sleeves, and free seminars in case there are system application updates.

Perceived disadvantages of being a gig worker

One significant disadvantage that both groups of gig workers face is the lack of security of tenure. PO4, PO6, PO7, and PO8 mentioned that since they did not have a formal employee–employer relationship, the client can quickly retract for whatever reason and without prior notice. This meant a lack of assurance of a regular flow of income since income largely depended on the number of bookings or clients they get. This also meant that they have no access to social safety nets, particularly, the government-mandated benefits such as Social Security System (commonly known as ‘SSS’), Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (commonly known as ‘PhilHealth’), Home Development Mutual Fund (commonly known as ‘Pag-IBIG’), or 13th-month pay. Instead, the gig workers have to process their government contributions themselves. They also do not receive other benefits such as private health insurance, vacation leave, overtime pay, or hazard pay.

Similarly, location-dependent gig workers also do not have access to sufficient medical benefits in case of work-related accidents. LD3 mentioned that a fellow Grab rider who had an accident during delivery received only PHP1,000 from Grab, and even that took time to process.

Another disadvantage was the commission rate or ‘cut’ that the platform gets. For example, the rider mentioned that Grab’s commission rate is pegged at 40%, which massively affects riders’ incomes, especially whenever oil prices increase. LD3, LD4, and LD5 added that it had been challenging to get incentives nowadays given the changes in their platform applications, which seem to favour the company instead of the riders.

Among purely online gig workers, one disadvantage was not getting prompt responses from colleagues in case some escalations have to be attended to. PO4 said that resolutions of complaints might take time given that the work setup is virtual. Moreover, sudden and unpredictable work disruptions caused by extreme weather conditions, power interruptions, and slow internet connectivity were also disadvantages of their setup.

There are also instances in which clients take advantage of them. PO7 said there were instances when the client would ask her to deliver outputs that were already beyond the scope of work. Another negative aspect of shifting to purely online gig work is interpersonal communication, especially with office colleagues and friends. PO6, PO8, and PO10, for instance, missed the face-to-face interactions with colleagues in their previous work. They say it felt different whenever they talk to office friends and colleagues instead of talking about work with their family members. Another respondent, PO8, an extrovert, mentioned that he was now stuttering whenever he talked to other people. He attributed this to the sudden shift of his work to exclusively virtual.

Challenges and worries when the pandemic happened as a gig worker

Among the challenges that location-dependent gig workers faced included customer moods and behaviours. There were instances where customers took a long time to retrieve their delivery, incorrectly set the wrong location, or even did not show up. If ever customers cancelled their orders, the riders had to shoulder the initial cost of the food and then had to wait for several business days for their reimbursement from the digital platform. They also encountered irate customers who got upset when the food was late or when the food was not as appetising as shown in photos. These challenges generally affected the ratings or reviews they receive on the application.

Another challenge was gig worker safety while on the road or during their working hours. Specifically, these workers had to contend with poor road conditions, accidents, and robberies. They also faced the risk of not being covered by accident insurance if they carried overweight items. Given the perennial typhoons in the Philippines, these location-dependent workers faced further challenges during erratic or extreme weather conditions, delaying the delivery of goods, which in turn, would affect their incomes. They also encountered instances when there were technical problems with the application itself which delayed transactions. LD3 noticed that the platform tended to notify riders who are farthest from the merchants instead of those who are already near or within the area. LD3, LD4, and LD5 mentioned the incentives system which was seemingly designed unfavourably towards the riders.

Fraudulent bookings also remained a challenge for these riders, with LD7 noting that:

[Fake booking] has happened to me many times already. [What I do with the fake booking is] I eat it. I take it home and eat it with my kids to make them happy. (LD7)

The location-dependent workers also faced challenges when transacting with merchants. LD5 noted how some merchants take time to prepare their orders, which then results in delayed delivery.

Decreased bookings also became a challenge especially as the government started to relax quarantine restrictions. LD11 mentioned that in May 2020 or at the height of the pandemic, Grab delivery was booming – this allowed him to make deliveries almost six days per week. However, they eventually got fewer deliveries as quarantine restrictions were relaxed. LD7 also noted the seemingly fewer transactions that were coming in from Foodpanda, making settling his bills more challenging.

On the other hand, when asked about the challenges and worries that they had when the pandemic struck, the purely online gig workers generally expressed concerns about their health. PO2 asserted that health had become a major priority for them when the pandemic hit the country. Some also expressed their concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine, specifically its effectiveness and effects to them and their children.

For me, if the vaccine has 100% no or not really, I’m also a med tech before I did online teaching. Of course, we don’t know what the effect of the vaccine in the future will be because it was done fast. I am worried. It’s okay for me. Of course, I had my child vaccinated, I just worry a bit. What will happen in the next few years because of that vaccine. (PO1)

Me too, it took me a long time to decide. I just had my vaccine this January. So, my children kept on asking me to get one. Don’t worry about it, it doesn’t have anything. And then our vaccine is Astrazeneca right, it has a lot of disadvantages during that time, but I hope it wouldn’t have any bad effect. (PO5)

Another challenge was in terms of savings and earnings. The challenging times highlighted the importance of having income and savings to deal with the uncertainty. PO3 decided to get a life insurance plan to ensure that her family would still have earnings if something bad happens to her because of the pandemic. PO4 highlighted the importance of having enough savings in case someone in their family became sick and to suffice their daily needs. In terms of getting essential items such as food, the purely online gig workers found that their limited mobility made it difficult to do errands such as grocery shopping.

Another challenge for them was increased competition in the freelancing industry, especially for those who had been working in the industry pre-pandemic. PO6 mentioned that when the pandemic hit, the freelancing industry provided work-from-home opportunities for displaced workers for them to earn while they were stuck at home. The lack of personal connections with colleagues and other people, meant that online workers’ communication skills became blunt due to being isolated from their wider network.

Yes, I really miss it but I’m also now used to working at home as well, but I also miss talking to different people… Before, communication skills are being enhanced whenever you talk to different people, and you go to different places if you have a project that you need to bring your client because you bring them to the units that they are looking for. Now, more on focus on typing, encoding, checking of products that your team members did. So, they are really different. (PO2)

Coping strategies to the challenges and disadvantages as a rider (sentiments toward current work)

Location-dependent gig workers dealt with the challenges and disadvantages of their work by cancelling or avoiding bookings to seemingly unsafe areas, or when the parcels exceeded the allowable weight. They also avoided making deliveries during peak hours, when the weather was too hot or it was raining.

I have encountered one that has a lot of deliveries so now that I see the booking if I’m a bit uncertain because I’ve experienced one before, it had 3 boxes of frozen goods, it exceeded the weight for our bag. Maybe safety first. That is why if I see that it is frozen, I usually cancel it. I don’t want to do it again because of what happened before. You can’t complain if you’re there already, they will report you. You can see what your parcel is, so for safety purposes as well because it’s hard. (LD4)

When asked about the strategies to cope with the challenges of being a purely online gig worker, the respondents answered that they attended training, workshops, and webinars to upskill or learn new skills and knowledge in order to be up-to-date with the current trends in their field. Another strategy was good communication with the clients at the start of the project to level-off expectations.

I am happy with my client. at the very start we agree on the scope of skills or scope of job that I will perform for them. Even the rates, working hours. Sometimes there’s miscommunication, that’s where problems start. It’s important to have good communication and setting of expectations at the start so you won’t encounter problems. (PO7)

Meanings of ‘job security’

When asked if gig work provides the respondents job security, several of them said yes, mostly those doing purely online gig work. PO3 said that she felt secure in her freelancing job as long as she has work, and that job security in freelancing is almost similar to job security in a traditional job. Job security, she added, still depends on several factors such as the company being financially stable amid a crisis.

Well for me, I consider it to have a job security though it is freelancing, as long as you have work then there are still a lot of opportunities for freelancers [or gig workers] though you do it virtually but I said there are a lot there so this is still also considered as a job security. There is still job security. (PO3)

PO2 mentioned that his current work of encoding products from the United Kingdom is deemed essential. Hence, he felt that his current work has job security. PO9 said that while job security may not be guaranteed, his current work in Kumu felt secure as long as they have talents who do live stream on their application. PO6, PO8, and PO9 highlighted the importance of establishing a good working relationship with their clients to ensure job security.

Among location-dependent gig workers, however, many of them knew that their work did not provide job security. Specifically, LD3 and LD4 highlighted the fact that they did not have security of tenure in their current work as their income is irregular and largely dependent on the bookings they get daily.

Aspirations and long-term objectives

Near-term personal plans and goals

The FGD interviewees were also asked about their near-term personal plans and goals. Gig workers from both groups agreed about the importance of saving money to maintain liquidity, for emergency purposes, and to support their family.

PO2, PO3, and PO5 wanted to continue saving for the future because the future remains uncertain. LD4 mentioned that having an emergency fund was very critical especially that the pandemic is not yet over, while LD1 mentioned that he was saving up to help his ill mother.

I want to save in case of emergency like my mom who has cancer so that I can also help. I’m also ready in case there are scenes like that, I have funds. (LD1)

Knowing the lessons from this pandemic, we need to tighten our belts, set our wants at a later time and prioritise first our needs. It could happen anytime, the cases will increase again, then lockdown again and all of us will be affected. That’s what I see as a lesson to all of us. What we see now as a lesson we just need to continue it, then save, and save. There are still dates for duration, until when we are at category 1 or level 1. So, we need to be aware of our environment. We still need to follow our safety protocols especially with our deliveries. (LD4)

In the near future, some of the purely online gig workers claimed they would continue with their freelancing work. Specifically, PO4 mentioned that aside from his freelancing work, he is also learning new skills to gain more clients and other work opportunities.

That was also the case with some of the location-dependent gig workers, who also wanted to continue with their current work because it provided them income to support their family’s needs. In fact, LD8 aimed to get promoted from being a rider to becoming a dispatcher.

Even if I have a stable job, we can’t really say that our buyers are stable. If I get promoted, I want to become a dispatcher or the one who distributes parcels internally. (LD8)

Other gig workers including PO1 and PO3 planned to eventually go back to their previous work and get more stable jobs. PO1 added that she planned on being a medical technologist again once the country’s economy stabilised. Some location-dependent gig workers such as LD1 and LD11, citing the benefits of having a regular job, wanted to go back to being call centre agents given the decreasing bookings.

Moreover, others such as LD3 and LD5 wanted to become entrepreneurs because working as a rider was not secure employment. LD3 also highlighted investing in learning opportunities while earning as a Grab driver.

May be I’ll do business but not this time because the economy is not stable right now, it is just starting again. Maybe after a year, I’ll have Grab as a sideline and have a business. It will be half. (LD3)

You can [also] start studying business, to start one while you are still earning with Grab. You can invest in learning while you are still earning from Grab. (LD3)

Long-term aspirations in life

When asked about their long-term aspirations in life, some of the purely online gig workers such as PO1 and PO3 wanted to provide a better future for their family such as having their own houses.

My first goal right now is, right now my husband and I are building our house so I hope we can reach that, it will be finished. Then of course the insurances that I got because of the pandemic, though before pandemic I have life insurance already but because of the pandemic I got St. Peter’s as well just to be sure also. So that I’ll know that if something will happen to me or to my family, at least our expense budget will not be as big. Then of course save again. Then hopefully, I can go back to, after this will be okay, I can go back to being a med tech again. (PO1)

For my aspirations, maybe to reach my goals in life. To have my own house, for my family, I hope I reach that. And then of course, to save, savings, that is where emergency funds will come from, so there and stable work. Of course we don’t know what will happen, if this will continue, if the pandemic continues, what will happen to our work if it still continues. So that is one of my aspirations, to have a stable and permanent job also. (PO3)

That was also the general response among location-dependent gig workers, especially LD1, LD2, LD3, LD4, LD7, LD9, and LD11, who said that they also wanted to provide car and schooling for their families.

To have my own house, my own car. Not all the time I’ll be a rider, this is the stepping stone in other words. This will be the ground experience before you go to the good part. That’s it. (LD3)

Some purely online gig workers wanted to get a more stable job (PO3) while others wanted to persevere to be able to provide their daily needs (PO2) or to venture into business (PO8). Location-dependent gig workers such as LD1, LD2, LD3, LD4, LD7, LD9, and LD11 wanted to persevere and work hard to get more bookings in order to gain more earnings.

Support needed

Support needed from platform or clients

In terms of support needed from their clients or platforms, both groups of gig workers requested the provision of social safety nets such as SSS, Pag-IBIG, and PhilHealth. PO5 suggested that foreign clients or foreign employers must shoulder at least half of their contributions. They believed that there should be a law that when they hire a Filipino, they should shoulder at least half of the employment benefits. (PO5)

Both groups also claimed a need for other benefits. Among purely online gig workers, they were requesting private medical insurance, electricity allowances, paid leave, and laptop equipment. Location-dependent gig workers sought benefits such as private medical insurance, grocery packages, vitamin supplements, cash incentives, PPEs, face masks, and rubbing alcohol.

The purely online gig workers, especially PO7, PO8, and PO9, wanted to have personal or face-to-face annual gatherings with their fellow gig workers while PO10 wanted a more hybrid work setup. On the other hand, location-dependent gig workers said they needed an increase in the delivery rates or fares of the riders; this was especially the case for deliveries to far-flung areas, given the recent increases in fuel prices. Specifically, LD4 and LD7 suggested that platforms such as Lalamove and Grab should provide fuel subsidies, perhaps linking up with gas stations to provide discounted fuel prices. In terms of the platform or application itself, workers sought better monitoring and security to avoid fraudulent buyers or scammers. They argued the need for prompt fixing of system glitches to avoid loss of transactions and increase the volume of transactions. Lastly, they also said they wanted to have an avenue where they could voice their concerns on matters such as working conditions, with LD9 mentioning that he hoped that their platforms would listen to their concerns.

Support needed from the government

The purely online gig workers said they hoped that labour laws would be updated to reflect the existence of purely online work, especially in terms of safeguarding their rights against fraudulent customers and in the filing of income tax. PO7, PO8, and PO10 hoped that the next administration would be able to pass laws or policies that would protect their rights as gig workers in general and provide sanctions for international clients who might violate the contract.

This might be it, before the clients goes through us. They should go through a platform or whatever. There should be a law on bond for clients with a certain amount just in case they leave us, at least we are still compensated. Whether the work contract is finished or not. (PO8)

PO4 lamented that the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR), the Philippines’ national tax authority, remained somewhat clueless on their freelancing work, and saw it as a novel type of work. Others asserted that the government should require the workers’ clients to provide them with government-mandated benefits. PO6 and PO8 specifically requested that the government provide free psychological services to gig workers. PO5 said that the government should also provide a one-stop digital platform where they could file their government-mandated benefit contributions. Location-dependent gig workers said they needed assistance from the government to include COVID-19 cash assistance and grocery packages.

Discussion

The research for this paper sought to gather insights for developing recommendations for the gig economy. The article has explored the experiences of individuals in the gig economy before and during COVID-19, focusing on their motivations for transitioning to this work and the challenges they encountered. Our study reveals that gig work respondents value gig work for its flexibility in managing their own schedules. On the other hand, gig workers are also advocating for increased government support and regulation to safeguard their well-being.

Organisational factors, and individual and family factors

The results of the FGDs show that organisation factors such as flexible work schedules play a major role in choosing to do gig work. In general, the purely online gig workers preferred working from home. Some of them even preferred working from home precisely because they did not need to commute to work, and so could more easily attend to family responsibilities. This result is similar to the studies of Aczel et al (Reference Aczel, Kovacs, van der Lippe and Szaszi2021) and Vyas and Butakhieo (Reference Vyas and Butakhieo2021); the former found that about 66% of researchers preferred to work more from home, while the latter cited a survey by Wong and Cheung (Reference Wong and Cheung2020) where about 82% of respondents in Hong Kong preferred working from home.

On the other hand, location-dependent gig workers said they preferred working inside an air-conditioned or temperature-controlled office even if they had to commute in their previous work. Doing food or parcel deliveries means they are constantly exposed to the elements such as hot midday temperatures or heavy rains.

We also found that while both groups generally saw gig work positively as it offered flexibility in terms of work schedules and work location, some workers, especially purely online gig workers, felt sad at the loss of personal interaction with their colleagues and other people. This was also a disadvantage of working from home cited by respondents in a study by Kaufman and Taniguchi (Reference Kaufman and Taniguchi2021). This feeling of loneliness may even be stronger among younger gig workers since older people were seen to spend more time with other social activities and gatherings (Clair et al Reference Clair, Gordon, Kroon and Reilly2021; Nyqvist et al Reference Nyqvist, Victor, Forsman and Cattan2016).

Another finding was the differing perceptions of job security and of what a good job means for purely online gig workers, compared with location-dependent workers. Many of the purely online gig workers felt that they had job security, at least as long as the work kept coming in. Moreover, the purely online workers in this study also found that they were more productive compared to working at the office. They perceived that they performed well despite the heavy workload because they appreciated the flexibility of being considered a contractor (Ray et al Reference Ray, Kenigsberg and Pana-Cryan2017). This contrasts with Kraimer et al (Reference Kraimer, Wayne, Liden and Sparrowe2005) and De Angelis et al (Reference De Angelis, Mazzetti and Guglielmi2021 who found that workers who do not feel secure at their jobs performed worse.

Outcomes of work, and outcomes for daily life

Discussions related to outcomes of work and life surfaced during the FGDs. Gig workers identified experiences such as increased work-life balance because they were their own bosses and could manage their own schedules. As a concomitant, they appreciated the potential and actual increase of their incomes. This is in line with the findings of Berger et al (Reference Berger, Frey, Levin and Danda2019), which, given the right motivations and their decision to shift careers, often improved a gig worker’s well-being and income. These workers also appreciated the increased incomes that came from flexible schedules which allowed multiple projects that, in turn, allowed multiple income streams for them (Sarker et al Reference Sarker, Taj, Sarkar, Hassan, McKenzie, Al Mamun, Sarker and Bhandari2024).

In contrast, location-dependent gig workers did not feel secure with their current jobs as they depended on the bookings they could obtain. Studies by Kraimer et al (Reference Kraimer, Wayne, Liden and Sparrowe2005) and De Angelis et al (Reference De Angelis, Mazzetti and Guglielmi2021) reveal this may worsen, the longer they experience job insecurity. Some saw working as a rider as temporary because they ultimately wanted to become entrepreneurs. Given that their gig jobs may be considered low-skilled, they may eventually need to upskill to get more secure and higher-paying jobs (Serafica & Oren Reference Serafica and Oren2022).

Furthermore, because gig workers lacked the benefits that traditional workers have, there was concern about the former group’s welfare in the long term, especially given the need to provide for old age. While SSS is theoretically mandatory, even among the self-employed and payments can be made through multiple payment channels such as GCash, gig workers found it difficult to pay for their SSS. This, in turn, jeopardises their future retirement.

The FGD participants also raised their concerns about government support and regulations during the discussions. The location-dependent gig workers mostly sought government assistance for specific items such as grocery packages and cash assistance. The purely online gig workers raised broader concerns about the need for protections and regulations for gig workers, currently not available to gig workers, given their status as so-called contractors (Powell Reference Powell2015). In the COVID-19 pandemic, the lack of sick leave benefits meant that workers often had to work even when sick, leading to work-related injuries (Howard Reference Howard2016).

There also seemed to be confusion among purely online gig workers arising from the government’s treatment of gig work and freelancing in terms of taxation. Some of the respondents mentioned that they have not been paying taxes because of unclear or complicated government regulations related to taxing gig work. This was also noted by Serafica and Oren (Reference Serafica and Oren2022) who found that online workers were getting contradictory advice from BIR and were intimidated by the confusing paperwork of declaring their income and filing their taxes. Serafica and Oren (Reference Serafica and Oren2022) added that there were multiple and seemingly overlapping BIRs individual taxpayer classifications depending on, among other things, the types of work and employment in place. There were also difficulties in classifying gig workers. The Department of Labor and Employment issued an advisory in 2021 stating that a gig worker’s employment status is on a case-by-case basis and depends on factors such as the employer’s right to control the employee on how work should be done (Samson Reference Samson2021). These instances are also compounded by the absence of reliable data to understand where governments could implement policies for the welfare of gig workers (Tacadao et al Reference Tacadao, Navarosa, Bondad and Sto Tomas2023). Simply put, this situation not only lowers gig workers’ welfare but also deprives the government of needed revenue given that BIR cannot ensure the collection of the correct amount of taxes from gig workers (Serafica & Oren Reference Serafica and Oren2022).

Gig work post-COVID-19 in the Philippines

In 2022, the Philippines began cancelling quarantine measures, such as the mandatory face mask wearing in both indoor and outdoor areas, and from July 2023, restrictions on public transport were lifted (Cupin Reference Cupin2022; De Leon Reference De Leon2023). Even as the Philippine economy slowly reopened, the gig economy still seemed to offer growth opportunities. Location-dependent gig workers based in the Philippines were expecting growth in client demand from overseas (Payoneer & GCash 2022) They also hoped to earn more if they could identify more foreign clients rather than just providing services to Philippine-based clients (Payoneer & GCash 2022). On the other hand, an Asian Development Bank (2023) study surveying GrabFood drivers in the Philippines found that about 95% of them want to remain as GrabFood drivers post-pandemic.

The Philippines has also acknowledged this new reality. The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA), the Philippine government’s technical-vocational education agency, began adopting measures such as the official recognition of so-called ‘micro-credentials’. These offer learners and workers short courses that allow for constant upskilling, and so prepare them for new job opportunities in the gig economy (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority 2022). TESDA has also provided free Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) through the TESDA Online Program (TOP), in which learners can take short courses on topics such as information and communications technology (ICT) (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority 2024). In recognition of the likelihood of continuing gig work in the economy, the Philippines government has also been taking steps to protect gig workers. In February 2023, the Freelance Workers Protection Act was approved in the House of Representatives (Quismorio Reference Quismorio2023). This Act includes protections such as the right to a written contract, the right to hazard pay when needed, and access to some initial down payments at contract signing (Quismorio Reference Quismorio2023).

Limitations of the study and recommendations for future research

It is important to note that the findings of this exploratory study may have limited generalisability. First, they are applicable mainly to the FGD respondents. Additionally, data collection took place in the first half of 2022, a period when generative AI technologies were not yet fully developed and readily available. This aspect is important because tools like these have significantly transformed work dynamics in the gig economy by automating tasks and reshaping skill demands (Gupta et al Reference Gupta, Mufti, Sohail and Madsen2023). Nonetheless, the results offer valuable insights into the experiences of respondents and can guide policymakers in formulating policies to address the challenges faced by gig workers.

One key recommendation for future research is to develop an estimated measurement of the gig workforce in the Philippines, categorised by the type of gig workers according to the nature of their tasks. This data would be essential for industries and policymakers to address challenges, maximise opportunities, and understand the challenges encountered by gig economy workers as found in other research such as that of Tacadao et al (Reference Tacadao, Navarosa, Bondad and Sto Tomas2023). Measuring the entire gig workforce may be too difficult, but demographers could initially focus on specific sectors or industries in partnership with gig economy platforms.

Policy recommendations and conclusion

In many ways, the gig economy may contribute to the path toward economic development, especially in developing countries. The easy signing-up process and the new types of jobs created with the rise of the gig economy have lowered the barriers to entry for potential gig workers, often, providing them the opportunity to earn higher incomes. As mentioned in earlier sections, countries such as the Philippines have now acknowledged that the gig economy is here to stay. However, they can only fully take advantage of all the benefits of the gig economy once reforms and regulations in labour laws that reflect the realities of the 21st-century labour market are enacted. Because of their distinct position in the labour market, gig workers in the Philippines require policy solutions that correspond to their conditions.

Given the more dynamic nature of the labour market in the coming years, one recommendation is legally recognising gig workers and giving them rights and protections. The government could work towards legally recognising them as a separate category of workers with rights and protections that cater to their unique situation (De Stefano Reference De Stefano2016; Graham et al Reference Graham, Hjorth and Lehdonvirta2017; Katiyatiya & Lubisi Reference Katiyatiya and Lubisi2024). Moreover, establishing a definitive categorisation of their employment status would allow them to get specific labour protections and benefits (De Stefano Reference De Stefano2016). In turn, this would enable access to government-mandated benefits such as SSS, PhilHealth, and Pag-IBIG, among others. As noted above, the House of Representatives has already passed the Freelance Workers Protection Act, although it has yet to be passed by the Senate (Quismorio Reference Quismorio2023).

Aside from providing legal recognition to gig workers, there is also the need to encourage the upskilling and reskilling of the Philippine labour force in general. The ever-changing landscape in the gig economy means that workers doing remote work have to compete with other remote workers across the world. Together with the risks of job layoffs due to the rise of automation in light of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, gig workers working in low-skill jobs should therefore be upskilled for them to move up the career and skills ladder, reap higher wages, and more easily switch careers and find new jobs (Serafica & Oren Reference Serafica and Oren2022).

The Philippines has already begun recognising ‘micro-credentials’ and has even introduced free online courses through TESDA (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority 2022; Technical Education and Skills Development Authority 2024). Nevertheless, barriers to upskilling, such as poor internet access, remain, preventing people from accessing online upskilling courses (Bhandari Reference Bhandari2023). Therefore, a further policy recommendation is that the government should increase investments in internet infrastructure to improve the speed and quality of internet service in the Philippines.

This exploratory study sought to answer the question of the motivations behind workers’ transition to gig work, and the outcomes and challenges they face in this sector. This study has focused on the context of pre-COVID-19 and during the early years of COVID-19, the early 2020s. The study revealed that gig workers appreciated the flexibility of managing their own time, yet they also expressed a need for increased government support and regulation to ensure that their welfare is protected. While gig work has created additional opportunities for many, certain drawbacks have emerged over time. It is essential for the government to intervene to safeguard the well-being of these workers. Additionally, as technology evolves rapidly, it is essential for labour laws and regulations to adapt to these new circumstances.

Christopher Ed Caboverde is a researcher whose topics of interest includes livable and sustainable cities, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), human capital development, and competitiveness. He also co-authored peer reviewed journals on topics such as SME profit growth, environment regulations, and the telework potential in the Philippines. He has a Master in Applied Economics degree from De La Salle University Manila and a Bachelor of Arts Major in Political Science and Minor in Economics degree from Ateneo de Davao University.

John Paul Flaminiano is a researcher whose works focus on SME competitiveness, technology adoption, telework and the gig economy. He is currently a Project Consultant at AIM-RSN-PCC, where he leads the study on AI adoption among manufacturing SMEs across various Southeast Asian countries. He is also a Ph.D. Candidate at the Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation (APU) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, where his dissertation explores the dynamics of technology adoption in the hospitality sector. Paul previously served as Associate Director and Senior Economist at AIM-RSN-PCC and worked as a Research Analyst in the Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department at the Asian Development Bank. He has published in several international peer-reviewed journals, focusing on SME competitiveness and entrepreneurship, economic development, and telework. He earned a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Ottawa, a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of the Philippines, and a Bachelor’s degree in Economics from the University of Manitoba.