Introduction

For decades, Indigenous peoples have been decrying the misappropriation of their knowledge and resources, and concomitantly third parties obtaining patents over the gains of this misappropriation.Footnote 1 This misappropriation has occurred partly as a result of conflicting norms around knowledge. For example, if not covered by a nondisclosure agreement or current Western intellectual property (IP) form, Western researchers have assumed that knowledge and resources are in the public domain and thus free to use without constraints, though, in fact, they might be regulated by laws and norms of the peoples from whom the knowledge or resources came. At the same time, Indigenous knowledge is often not recorded the same way as Western knowledge, and is often orally transmitted, which has meant that intellectual property offices have not located it when deciding on whether an invention in a patent application is new or nonobvious. This has allowed for the knowledge and resources of Indigenous peoples, and inventions derived from these, to be patented.

On 24 May 2024, member states of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) adopted the Treaty on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge (“the GRATK Treaty”) with the aim of addressing such patents.Footnote 2 Declared a historic triumph,Footnote 3 the objectives of the GRATK Treaty are to “enhance the efficacy, transparency and quality of the patent system with regard to genetic resources [(GRs)] and traditional knowledge [(TK)] associated with genetic resources”Footnote 4 and to “prevent patents from being granted erroneously for inventions that are not novel or inventive with regard to genetic resources and traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources.”Footnote 5 Patents are time-limited exclusive rights that are granted for inventions that are new, nonobvious, and capable of industrial application.Footnote 6 These exclusive rights are granted in return for a complete disclosure of the invention by the applicant in the form of a specification setting out the details of how the invention may be carried out.Footnote 7

The GRATK Treaty purportedly achieves its objectives, and thus protects IndigenousFootnote 8 peoples’ and local communities’ (IPLCs’) genetic resources and knowledge,Footnote 9 by requiring that patent applicants disclose the country of origin or source of GRs and/or the provider or source of any “associated traditional knowledge” (ATK) their claimed invention is based on.Footnote 10 Patent offices are to use these disclosures to better examine a patent vis-à-vis novelty and inventive step (nonobviousness).Footnote 11 It might otherwise be almost impossible for patent examiners to realize that the claimed invention is based on these GRs or ATK, because it is not always apparent from the claimed invention disclosed in an application, or the relevant knowledge is not accessible to patent offices.Footnote 12

While the GRATK is an important step forward in WIPO’s efforts to protect TK, the WIPO GRATK Treaty may be critiqued on many grounds.Footnote 13 For the purposes of this article, we note that a core issue with the treaty lies in the maximum standards the treaty sets for possible sanctions and remedies against patent applicants who do not correctly comply with the disclosure requirement. The WIPO GRATK Treaty allows parties to have “appropriate, effective, and proportionate legal, administrative, and/or policy measures to address a failure to provide the” required information.Footnote 14 However, only in limited cases of fraud may there be post-grant sanctions, and applicants must be given the opportunity to rectify any failure to disclosure before sanctions may be imposed.Footnote 15 Not being able to implement effective sanctions in the absence of fraud may create incentives for applicants to not disclose information in ways that do not amount to fraud, such as wilful blindness or misrepresentation.

At the time of writing, Aotearoa New Zealand had not signed or implemented the GRATK Treaty. Here we argue that it should not, as its law and Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand (IPONZ) practice already go beyond the provisions of the GRATK Treaty in many ways. Moreover, as we argue, signing and ratifying the GRATK Treaty would place limits on Aotearoa New Zealand’s ability to address Māori interests and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi)Footnote 16 obligations. At the same time, to the extent that the GRATK Treaty might go further than Aotearoa New Zealand law and practice, there is nothing to stop the legislature and IPONZ from developing its law and practice and retaining the best of both worlds – to enact laws that fit the local situation without being bound by any maximum standards set out in the GRATK Treaty.

In earlier work, we noted that the IPONZ patent application form already has a disclosure checkbox requiring applicants to acknowledge where they believe the claimed invention is “derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from New Zealand indigenous plants or animals”,Footnote 17 but that it was unclear what the consequences might be of an incorrect disclosure. Indeed, the Aotearoa New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) acknowledged that such disclosures are “optional.”Footnote 18 Furthermore, since the entry into force of the Patents Act 2013, the wording of the declaration in the checkbox and the accompanying text has changed numerous times. In order to obtain a better understanding of IPONZ practice with respect to disclosure requirements, including the role of the Patents Māori Advisory Committee (PMAC) in the process, we filed two Official Information Act 1982 (OIA) requests with IPONZ seeking information on the establishment and subsequent changes to the application disclosure checkbox and the patent register portal, as well as the consequences of ticking, or failing to tick, the disclosure checkbox. Drawing on the response of IPONZ to this request, in this paper, we clarify the potential consequences for failure to comply with the disclosure requirement. Analyzing Aotearoa New Zealand’s existing patent law that allows for opposition, reexamination, or revocation on the basis of fraud, and also the lesser legal standards of false suggestion and misrepresentation, we argue that, in certain circumstances, incorrect use of the checkbox could result in an application being declined or a patent being revoked. Thus, introducing a maximum standard that does not allow for patent invalidity except in the case of fraud would weaken Aotearoa New Zealand’s current law, which allows for opposition or invalidity in cases of false suggestion or misrepresentation.

This paper commences with an overview of the measures set out in the GRATK Treaty with respect to disclosure. This is followed by analysis of the role of the PMAC in Aotearoa New Zealand and existing patent practice with respect to disclosures, or failure to disclose, consistent with the existing application form, drawing on information released by IPONZ under the OIA. The paper then engages in analysis of the application of existing laws relating to fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation to disclosure obligations and concludes with an assessment of the impact of the GRATK on domestic law and the ability of the patent system to protect the interests of Māori and meet Crown obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

The GRATK Treaty: An administrative measure

The GRATK Treaty is the first and, at the time of writing, only instrument to arise out of more than 20 years of discussions at the WIPO Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore (IGC) on the protection of IP, GRs, TK, and traditional cultural expressions (TCEs). It is not rights based, but rather an administrative measure designed to improve the patent system by providing more information to patent examiners and preventing the grant of so-called erroneous patents. The substantive section, Article 3, has two parts: The first relates to claimed inventions that are “based on”Footnote 19 GRs and the second to claimed inventions that are “based on traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources.” Regarding GRs, Article 3.1 of the GRATK Treaty mandates contracting parties to require patent applicants to disclose “(a) the country of origin of the genetic resources, or, (b) in cases where the information in Article 3.1(a) is not known to the applicant, or where Article 3.1(a) does not apply, the source of the genetic resources.”Footnote 20 Article 3.2 of the GRATK Treaty requires contracting parties to require patent applicants to disclose: “(a) the Indigenous Peoples or local community, as applicable, who provided the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources, or, (b) in cases where the information in Article 3.2(a) is not known to the applicant, or where Article 3.2(a) does not apply, the source of the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources.”Footnote 21

The GRATK Treaty restricts the sanctions that may be applied in the event that a party fails to comply with the disclosure requirements. Specifically, Article 5.3 provides that “no Contracting Party shall revoke, invalidate, or render unenforceable the conferred patent rights solely on the basis of an applicant’s failure to disclose the information specified in Article 3 of this Treaty.”Footnote 22 Applicants must be given the “opportunity to rectify a failure to disclose the information required in Article 3 before implementing sanctions or directing remedies.”Footnote 23 Contracting parties may only exclude the opportunity to rectify a failure to disclose in cases of “fraudulent conduct or intent”Footnote 24 and may “provide for post grant sanctions or remedies where they has been fraudulent intent in regard to the disclosure requirement.”Footnote 25

Disclosure and the Patents Māori Advisory Committee

The law

In force for 60 years, the Patents Act 1953 made no specific reference to Māori or their perspectives and concerns.Footnote 26 A significant tranche of the review of the 1953 Act related to Māori concerns, particularly in relation to biotechnology.Footnote 27 The focus was on biological resources, indigenous life forms, and the patenting of related inventions including the genetically modified, though “traditional knowledge” in a broader sense was also discussed.Footnote 28 The review evaluated concerns around the use of mātauranga Māori (without prior informed consent (PIC)), the potential value of databases of mātauranga Māori to be used by patent examiners, and how Māori should be consulted on relevant patent applications.Footnote 29

The resultant Patents Act 2013 created the PMAC, with members who must, “in the opinion of the Commissioner,” have knowledge of te ao Māori (the Māori worldview) and tikanga Māori (Māori protocol and practice).Footnote 30 The role of the Committee is connected to a general exclusion from patentability of inventions the “commercial exploitation” of which would be contrary to “public order” or “morality.”Footnote 31 In assessing this exclusion, the Commissioner may seek advice from the PMAC or any person that the Commissioner considers appropriate for assessing this.Footnote 32 A separate part of the act then stipulates that it is the Committee’s function to advise the Commissioner on whether a claimed invention is derived from “Māori traditional knowledge” or “indigenous plants or animals” and, if so, whether “the commercial exploitation of that invention is likely to be contrary to Māori values.”Footnote 33

The practice

Neither the Patents Act 2013 nor its 2014 Regulations provide any guidance on what would trigger (or lead to) the Commissioner of Patents to seek the advice of the PMAC. The legislation does not clarify the link between the provision under which the PMAC may be asked to provide advice (the exclusion from patentability due to public order/morality), on the one hand, and that the invention may be derived from Māori TK, or indigenous plants or animals, and its commercial exploitation may be contrary to Māori values (the role of the Committee), on the other hand. Note that what the Commissioner could consider to be contrary to public order/morality is broader than the specified functions of the PMAC, including other concerns that Māori might have that are not related to indigenous plants or animals, or the commercial exploitation of which might not be contrary to Māori values – we return to this subsequently.

Presumably, before seeking the advice of the PMAC, there must be some realization that the role of the Committee might be implicated. This could be a difficult task, given that this knowledge is often not well published, even if not secret, and patent examiners are typically trained in Western science and engineering.Footnote Footnote 35 In order to assist patent examiners, since the entry into force of the Patents Act 2013, in 2014, the IPONZ patent application form has included a checkbox for patent applicants to indicate certain information regarding “traditional knowledge.” There have been three iterations of this – see Figure 1.

Figure 1. IPONZ Patent Application Checkbox.Footnote 34 (a) From 2014 to April 2023. (b) From April 2023 to November 2023. (c) From November 2023 to present.

The PMAC did not provide any feedback on these changes, though they were advised of them. Notably, the latest iteration is the most detailed, closely mirroring wording from the Patents Act 2013.Footnote 36 According to information released by IPONZ in response to our OIA requests, the change was made “to align [it] with the primary purpose of this field, and in part due to incorrect and inconsistent use of this field by patent applicants.”Footnote 37 We return to the potential legal implications of the current wording, particularly that the applicant “submits,” subsequently.

From checkbox to PMAC

Checking the box on the patent application form does not mean that the application is automatically referred to the PMAC. While correctly using the checkbox to indicate that an application relates to Māori TK or New Zealand indigenous plants or animals would mean that “the application will meet the general assessment criteria and be referred to the Committee,” the “field however is not always used correctly or consistently by patent applicants.”Footnote 38 Thus, if the “traditional knowledge” field is checked by an applicant, this (as well as any accompanying documents) is checked during the examination process.Footnote 39 The assessment of whether to refer an application to the PMAC is made during the examination process and “is based primarily on the subject matter of the application, but also includes checking the traditional knowledge field and any additional documentation provided.”Footnote 40

Recall that the determination of whether “an invention claimed in a patent application is derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from indigenous plants or animals” falls within the remit of the PMAC.Footnote 41 Yet the foregoing would indicate that it is not the PMAC that assesses whether a claimed invention is derived from Māori TK or from indigenous plants or animals. This is supported by Draft Terms of Reference for the PMAC (also released in response to the OIA requests),Footnote 42 which state that “Patent applications received by IPONZ are to be assessed by IPONZ examiners to determine whether the invention claimed is, or appears to be, derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from indigenous plants or animals,” or “Applicants may also self-identify cases which have potential to conflict with Māori values.”Footnote 43 In contrast, “The Committee will consider the patent applications forwarded to it, and advise whether the commercial exploitation of that invention is likely to be contrary to Māori values.”Footnote 44 The Draft Terms of Reference further state that the Committee’s advice is to contain an indication of whether the commercialization of the claimed invention is likely to be contrary to Māori values or not. The Draft Terms of Reference do not state that the Committee’s advice has to indicate if there is derivation from Māori TK or New Zealand indigenous plants or animals.

Hence, IPONZ examiners and applicants are to assess derivation, whereas the PMAC is to assess whether the commercial exploitation is likely to be contrary to Māori values. Note that IPONZ examiners are to “have regard to guidelines to be determined in consultation with the Committee”Footnote 45 – these are yet to be developed more than 10 years since the PMAC was established. Arguably, the division of tasks between IPONZ examiners and applicants, on the one hand, and the PMAC, on the other hand, is not consistent with the legislation. The PMAC has statutory functions of providing advice on both derivation and whether the commercial exploitation is contrary to Māori values. While the use of the application checkbox is highly helpful, and the nature of the application process implicitly requires that an examiner assesses whether there is derivation from Māori TK or from indigenous plants or animals, this should not remove the PMAC’s function of providing advice on this.

In practice, and contrary to the position outlined previously, the PMAC does consider both derivation and whether commercial exploitation is contrary to Māori values. The PMAC typically engages in a two-step enquiry: First, is the claimed invention derived from Māori TK or indigenous plants or animals; and second, if so, would the commercial exploitation of the invention be contrary to Māori values?.Footnote 46 This approach reflects the legislative provisions setting out the function of the PMAC.

It is worth bearing in mind that the Committee may “regulate its own procedure, subject to any direction given by the Commissioner,”Footnote 47 thus raising the possibility that the Committee may informally advise the Commissioner on applications not referred to it. That said, the Committee may not have the support required to stay apprised of the thousands of patent applications that IPONZ examines every year.Footnote 48 The Draft Terms of Reference provide the support of an “expert advisor” (experienced in practices and procedures of patent examination) and a “liaison officer” to liaise between IPONZ and the Committee “and provide administrative support.”Footnote 49 It is unlikely that a single “liaison officer” could provide the Committee sufficient administrative support across all patent application examinations.

PMAC’s advice

Contrary to Māori values

As of 14 July 2025, 35 patent applications showed as having checked the “traditional knowledge” field, and the PMAC had been referred 16 patent applications.Footnote 50 There was no overlap between these sets of applications. Of these applications, only two had been identified as likely “contrary to Māori values”Footnote 51 and subsequently abandoned, and the review of another application resulted in a request for additional information from the applicant before ultimately being found not likely to be contrary to Māori values.Footnote 52

As outlined in the foregoing, under the 2013 Act, if the decision is made to seek advice from the Committee, the statutory functions of the Committee and the exclusion from patentability are narrow. This is because the Committee must assess both the conditions of (1) derivation and (2) commercial exploitation being contrary to Māori values.Footnote 53 The Patents Act 2013 does not specify what would constitute “derivation.” In other words, where is the line between something that derives from Māori TK and something that is so distantly related to Māori TK that it could be said to be different? In its advice so far, the PMAC has not specifically dealt with this issue. However, when considering questions of derivation, the PMAC has taken the position that where the claimed invention is derived from indigenous plants or animals, it will necessarily involve Māori TK.Footnote 54

The term “commercial exploitation” comes from the ordre public/morality clauses of the 2013 Act and WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).Footnote 55 However, the act does not delineate the meaning of “values” or tell us whether this is something to be defined by IPONZ or the Committee. The IPONZ website states that the purpose of the PMAC (along with the other Māori Advisory Committees established for trade marks and plant variety rights), is to assess applications “under the context of values, concepts, practices and knowledge associated with Māori culture.”Footnote 56 In assessing whether a claimed invention may be contrary to Māori values, the PMAC has taken into account the extent to which Māori have an interest in the commercial exploitation of the indigenous plant or animal or the Māori TK.Footnote 57 In reviewing an application from ComvitaFootnote 58 for an invention derived from Mānuka honey, the PMAC requested information from the applicant as to how Māori will be involved in the commercialization of the invention.Footnote 59 In response Comvita provided information on potential in-kind and monetary benefits to Māori stakeholders.Footnote 60 In particular, Comvita stated that their business “aligns with Māori values to deliver a stronger commercial outcome for local Iwi landowners and New Zealand as a whole, enjoying trade, environmental and cultural benefits.”Footnote 61 Following this response, the PMAC advised that the commercial exploitation of the invention was not likely contrary to Māori values.

Relation to public order/morality exclusion

The Patents Act 2013 does not state whose public order or morality is to be assessed.Footnote 62 Logically, Māori concerns relating to public order or morality must sometimes be sufficient, as the Commissioner can seek the advice of the PMAC to make his or her decision on these provisions. But does it have to be all Māori or a significant proportion of Māori? Or would an iwi (tribe), a hapū (sub-tribe), or a kaitiaki (guardian) suffice? And does the role of the PMAC relate to public order, morality, or both? It is not clear if or how the PMAC has dealt with these issues.

Some guidance may be drawn from the Patent Examination Manual, which provides that public order refers to “the protection of public security and the physical integrity of individuals as part of society, and encompasses the protection of the environment.”Footnote 63 In contrast, morality relates to “the culture inherent in New Zealand society as a whole or a significant section of the community should form the basis for determining what behaviour is right and acceptable, and what behaviour is wrong or immoral.”Footnote 64 Taking the ordinary meaning of “values,” it would seem that Māori values comes under morality rather than public order. Indeed, guidance issued in 2008 in relation to considerations of morality under the old Patents Act 1953 specifically referred to Māori interests in determining whether use of an invention would be contrary to morality.Footnote 65

In contrast, the Waitangi TribunalFootnote 66 deemed that Te Tiriti o Waitangi guaranteed right to tino rangatiratanga (chieftainship) – as expressed through kaitiakitanga (guardianship) – over taonga (that which is sacred) must be a matter of public order (if not also public morality), because Te Tiriti o Waitangi is a constitutional document, which defines the New Zealand legal and social order.Footnote 67 Notably, the 2013 Act and the Waitangi Tribunal differ as to what exactly should be protected: Whereas the Waitangi Tribunal was (and is) very Te Tiriti o Waitangi-orientated and, thus, reflects protecting the role of kaitiaki (guardians) and public order, the 2013 Act is not so directed, and the use of the term “Māori values” would imply that morality is relevant.Footnote 68 This depends on what would fall into the concept of “values” and how the Committee would decide whether something is contrary to those “values.”

The decision

The Commissioner of Patents is not bound by the opinion of the PMAC but considers the Committee’s advice when deciding the broader question of public order or morality, allowing the Commissioner to balance competing interests. For example, the Commissioner could consider different Māori perspectives not represented by the PMAC. However, as an advisory committee, the Commissioner of Patents could theoretically deem the commercial exploitation of an invention not to be contrary to public order or morality, despite the PMAC advising that there is both derivation and contravention of Māori values, and notwithstanding the lack of any differing opinion.

Where an application has been referred to the PMAC, the applicant is advised of the fact and the outcome in the Patent Examination Report. Where there is the advice that the commercial exploitation of the invention is likely to be contrary to Māori values, applicants are provided with the opportunity to provide further information. As set out in the foregoing, 16 cases have been referred to the PMAC with two cases found to be likely contrary to Māori values and subsequently abandoned.Footnote 69 However, it is important to note that this is not the sole issue that was raised with these applications. Additional concerns were raised by the examiner with respect to issues such as novelty and obviousness.

An example of the potentially conflicting issues at play in review of applications by the PMAC is an application dealing with a bacterial strain with insecticidal activity where the bacterial strain was isolated in New Zealand and had insecticidal activity against two indigenous insect species.Footnote 70 This application was referred to the PMAC for advice. The PMAC was of the opinion that there was potential that the commercial exploitation of the invention was contrary to Māori values on the grounds that genetic modification of the bacterial strain “could be considered manipulation of whakapapa [(genealogy)]” and “may also be an issue relating to kaitiakitanga, mana [(authority)], and tapu/noa [(sacred/to be free of tapu)].”Footnote 71 The commercial use of the bacterial strain as an insecticide against indigenous insect species was also noted as potential “manipulation of whakapapa which has broader impacts on the relationship between the bacterial strain, the target species and the wider environment.”Footnote 72 However, the PMAC also noted that the alleged invention may be less toxic or harmful than other insecticides and may therefore “indicate that the commercial exploitation of the invention is less likely to be contrary to Māori values.”Footnote 73 The examination report concluded by stating that IPONZ had considered the advice of the PMAC and considered that the commercial exploitation of the alleged invention would not be contrary to Māori values.

In another case, dealing with an application for an invention derived from Mānuka honey,Footnote 74 the PMAC raised concerns regarding the exploitation of the invention. The application was the subject of extended correspondence between IPONZ and the applicant to obtain further information and satisfy the concerns of the PMAC, before IPONZ ultimately found the alleged invention not likely to be contrary to Māori values.

Capturing the data

On the public patent register, one has the ability to see whether an applicant checked one of iterations of the aforementioned boxes, and also (since April 2023) whether an application was sent to the PMAC. At the time of writing, one could search the register according to these two variables (see Figure 2), or see on individual patent filings whether the applicant had checked the box on their application and whether the application was referred to the PMAC (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. IPONZ Public Patent Register: what one sees in searching the register. (a) From 2014 to April 2023. (b) From April 2023 to November 2023. (c) From November 2023 to present.

Figure 3. IPONZ Public Patent Register: what one sees per patent case, as at 9 May 2025.

From 2014 to April 2023, one saw “Maori Conflict possible”Footnote 75 as a radio button and “traditional knowledge” as a check box. This was changed after, in 2021, having received significant interest in which applications were being referred to the PMAC, IPONZ began to investigate how it could make this information more publicly accessible. IPONZ:

found that the “Traditional knowledge” checkbox seemed to be being used regularly only by one attorney firm, who were ticking it for multiple applications (633 cases in April 2021) even if those didn’t seem to include any discernable traditional knowledge. In contrast, the “Māori conflict possible” radio button wasn’t being used at all; we understood it wasn’t functional for applicants.Footnote 76

This meant that the “Maori Conflict possible” box was not being used. According to IPONZ, “[i]n April 2021, there were only three cases with this box ticked (754232, 754241, 736052) and we don’t have records why.”Footnote 77 Until April 2023, the box was not “functional or editable on the client side,” and IPONZ was not using it to indicate anything. Furthermore, IPONZ considered that the term was “ambiguous”Footnote 78 and not related to wording from the Patents Act 2013. However, it should be noted that, while the terminology does not reflect the legislation, the Draft Terms of Reference for the PMAC refer the ability of the applicant to “self-identify cases which have potential to conflict with Māori values”.Footnote 79

In 2023, IPONZ decided to repurpose the “Maori Conflict possible” box to indicate when the office had referred an application to the PMAC.Footnote 80 While some information on the fact of referral and the decision of the PMAC may be set out in the Examination Report, detailed advice or information on the deliberations of the PMAC is not published along with other prosecution documents for a patent application but can be sought through an OIA request once an application is open for public access (OPI).Footnote 81

The consequences of failing to check the box

Can there be legal consequence?

Though MBIE has been discussing the possibility of introducing a mandatory disclosure requirement since 2018,Footnote 82 there is no statutory requirement in the Patents Act 2013 or Patents Regulations 2014 for disclosure of origin or source, and the changes made to the checkbox wording explained in the foregoing did not relate to MBIE’s work on such a requirement.Footnote 83 From IPONZ documentation and replies to our OIA requests, it appears that IPONZ believes that the checkbox cannot create a statement with any legal effect. Instead, they view it as a “voluntary declaration” to assist IPONZ, which does not relate to any requirement of the Act or Regulations and thus cannot bear any legal consequences.Footnote 84 To illustrate, when asked what the consequences are if an applicant fails to positively disclose, and the application is subsequently identified as being derived from “Māori traditional knowledge” or “New Zealand indigenous plants or animals,” IPONZ replied:

None. There is no requirement under the Patents Act 2013 or Patents Regulation 2014 for identifying that an application is derived from “Māori traditional knowledge” or “New Zealand indigenous plants or animals”.Footnote 85

We respectfully disagree. In the following, we explain why we disagree. While it is possible to incorrectly tick the checkbox, we focus on incorrectly failing to check it, as this may be more consequential. Applicants may be unlikely to knowingly incorrectly check the box if they believe this might hold up their application. At the same time, Māori are likely more concerned with failures to check the box if this results in an application not being referred to the PMAC when it should, than those who incorrectly check it but the examiner decides not to refer the application to the Committee.

Previously, the IPONZ guide on applying for patents stated that the “Traditional Knowledge” checkbox was “Optional – select this if the invention is derived from Maori traditional knowledge or from indigenous plants or animals.”Footnote 86 At that stage, when it was specifically stated that the field was optional, it was arguable that failure to check the box – even when one knew that the invention was derived from Māori TK or an indigenous plant or animal – may not have had any legal consequences. This was reinforced by the wording of the checkbox, which had no explanatory text next to the checkbox, and only help text above it, stating, “If the invention is derived from traditional knowledge please tick the checkbox below.” (See Figure 1.)

In contrast, in July 2025 (the time of writing), the IPONZ guide on applying for patents stated that, for the checkbox, “Tick this box if you believe that your invention is derived from Māori traditional knowledge, or from plants or animals indigenous to New Zealand. You may also choose to provide a document containing further details.”Footnote 87 At the same time, the application form itself had an explanatory text next to the checkbox stating that the “applicant submits the invention is derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from New Zealand indigenous plants or animals.” The application form also had help text, stating “If you believe that the invention may be derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from New Zealand indigenous plants or animals please tick the checkbox below. This provides you with the opportunity to provide additional information or submissions. More information relating to Māori IP can be found on our website.” The removal of the guidance that the field is “optional,” together with the increase in details around the checkbox – especially the wording “applicant submits” – adds to an applicant’s answer to the field having legal consequences. This is particularly in light of the law around fraud, false suggestion, and misrepresentation in relation to patent applications and good faith interactions between applicants and the patent office, discussed in the following.

Fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation

In Aotearoa New Zealand, one can oppose an application on the basis “that the applicant is attempting, or has attempted, to obtain the grant of a patent by fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation,”Footnote 88 or seek revocation of a patent because “the patent was obtained by fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation.”Footnote 89 One can also seek reexamination of an accepted application or a granted patented on the same bases.Footnote 90 A similar provision also existed in the 1953 Act, though this was limited to revocation on the basis that “the patent was obtained on a false suggestion or representation.”Footnote 91 To date, there have not been any court decisions on the 2013 provisions dealing with fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation, but there have been some decisions under the 1953 provision dealing with false suggestion or representation.

The inclusion of the term “fraud” in the 2013 Act suggests that “false suggestion” and “misrepresentation” are distinct concepts of a lesser severity. This interpretation is supported by earlier case law from both the United Kingdom (UK) and Aotearoa New Zealand,Footnote 92 which clarify that one does not have to commit fraud for there to be false suggestion and misrepresentation. What matters is that the behavior is “so material that it can be said that the Crown has been deceived”Footnote 93 or “was misled into granting a patent.”Footnote 94

Note that case law assesses false suggestion or misrepresentation vis-à-vis representations of being the “true and first inventor,”Footnote 95 as well as representations in the applicationFootnote 96 or in the patent specification.Footnote 97 As a result of the latter, a significant number of the cases assess arguments that are very similar to arguments made in relation to lack of utility (that the patent does not do what says it should do, or does not fulfil its promise),Footnote 98 and sufficiency (that the specification does not sufficiently allow the person skilled in the art to work the invention).Footnote 99

As to the application, fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation can arise from representations on the patent application (documents, forms, and declarations)Footnote 100 and from interactions between the patent applicant (or their attorney/agent) and the patent office.Footnote 101 Regarding representations on the patent application, T. A. Blanco White has argued that such cases are consistent with the statutory wording, whereas cases more akin to inutility are not.Footnote 102 With respect to written and oral interactions with the patent office, let us turn to the Aotearoa New Zealand decision Dow Chemical v Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha Ltd (ISK). Footnote 103 In this case, ISK was the patentee, which sued Dow Chemical for infringement. Dow Chemical sought to counterclaim that ISK obtained the patent by false suggestion and representation on two grounds. First, regarding false suggestion within the complete specification, Dow Chemical claimed that multiple “misleading, inadequate or incorrect” descriptions implying that one had made and tested certain samples and compounds, when this was not entirely correct, and to link the filing to a Japanese patent to enjoy its priority, constituted false suggestion that cumulatively materially affected the decision to grant the patent.Footnote 104 Justice Eichelbaum declined to strike out this part of the cause of action, finding that it was not plainly untenable and could be decided only at full trial.Footnote 105

Second, regarding misrepresentation during the prosecution process (which includes drafting and filing, as well as post-filing interactions between patent applicants (or their attorneys/agents) and the patent office), Dow Chemical argued that ISK asserting that the patent should be granted with priority to a Japanese patent, and that the complete specification “properly and accurately asserted the preparation examples, compounds, and herbicidal tests” was false representation. In discussing misrepresentation during patent prosecution, Justice Eichelbaum cited Therm-a-Stor Ltd v Weatherseal Windows Ltd, which related to interactions between a patent agent and the patent office. The patent agent had informed the patent examiner that they were eager to expedite amendments and finalize the patent due to ongoing infringement concerns. However, the patent agent failed to disclose that the proposed amendments were directly related to the alleged infringement. The England and Wales Court of Appeal agreed with the defendants that proceedings with the patent office “are necessarily ex parte and that they must be approached on the footing of the utmost good faith and full and frank disclosure of all relevant facts.”Footnote 106 This is because patent examiners are “fulfilling an exacting and important public function” that relies on “information given to him by the only interested party, the applicant.”Footnote 107

After noting Therm-a-Stor, Eichelbaum stated that “There is no scope for an allegation of absence of good faith unless it can be brought under the heading of false suggestion or representation. I see no ground for narrowing the scope of those expressions or limiting the stages of the application process at which they may be invoked, subject always to materiality.”Footnote 108 Thus, “[h]aving regard to these considerations and the remarks in the Therm-a-Stor case,” Eichelbaum ruled that the counterclaim was not clearly untenable such that it should be struck out.Footnote 109 In other words, patent invalidity cannot be founded in the absence of good faith, but that does not mean that the absence of good faith cannot found an allegation of false suggestion or misrepresentation, if it materially affected the grant. In Therm-a-Stor, the allegation of false suggestion was based on the patent agent being less than candid. In Dow Chemical v ISK, Eichelbaum refused to strike out that false misrepresentation could be based on representations made during the patent prosecution that relate to priority. Note the analogy that can be made between false suggestions/representations in relation to alleged priority documents and disclosures that affects prior art, all of which can affect patentability standards, such as novelty and inventive step.

Earlier cases tended to address only the concept of false suggestion without distinguishing it from false representation. This may be attributed to the legislative phrasing – “false suggestion or representation” – which arguably conflated the two. Notably, Dow Chemical v ISK discussed the two separately as this is how they were pleaded, as discussed in the foregoing; however, Eichelbaum did not discuss the difference between a false suggestion and a false misrepresentation. In contrast to earlier legislation, the 2013 Act clearly distinguishes between “fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation.”Footnote 110 Case law preceding the 2013 Act indicates that fraud is something worse than false suggestions or misrepresentation, and, potentially, the standard for showing misrepresentation is different from that for showing false suggestion.

When Aotearoa New Zealand implemented its 2013 Act, it copied the wording from the Australian Patents Act 1990,Footnote 111 which has been interpreted and applied by Australian courts.Footnote 112 This case law indicates that “fraud” has its common law meaning (though it has never been applied). Other than the addition of “fraud,” there appears to be no substantive difference between the earlier legislative phrase “false suggestion or representation” and the more recent formulation “fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation.” While the Australian courts have indicated that “false suggestion” and “misrepresentation” have different meanings, they have not clearly delineated the two, as in Aotearoa New Zealand,Footnote 113 and any difference has thus far not been relevant to any decision.

The lack of definitive case law – in either Aotearoa New Zealand or Australia – provides significant interpretative scope within the definitions of “fraud,” “false suggestion,” and “misrepresentation” in Aotearoa New Zealand. Of course, “fraud” has a well-understood legal meaning in Aotearoa New Zealand law, and it is unlikely to be interpreted wholly differently within patent law. That said, we argue that a failure to correctly use the TK checkbox on one’s patent application could implicate either fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation and result in patent invalidity if it materially affected the grant. To illustrate, if an applicant “believe[s] that the invention may be derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from New Zealand indigenous plants or animals” but does not check the box indicating that the “applicant submits the invention is derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from New Zealand indigenous plants or animals,” this could constitute fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation, depending on the state of the applicant’s knowledge and their intention. This failure to check the box could mean that relevant prior art is not located (affecting the assessment of novelty and inventive step) or an application is not sent to the PMAC, either of which could materially affect the grant.

It should not matter that the checkbox is not a legally mandatory disclosure. The case law on fraud, false suggestion, and misrepresentation, as discussed in the foregoing, does not necessarily relate to behaviors relating to specific legal requirements but to interactions with the patent office (including withholding information) that patent examiners should be able to rely on to undertake their public functions. The checkbox is part of the application form. It states that applicants should check the box if they “believe that the invention may be derived from Māori traditional knowledge or from New Zealand indigenous plants or animals.” Not checking the box when one does have this belief constitutes fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation. If this materially affects the grant, the patent (application) should be revoked (opposed).

Note that the potential use of the fraud, false suggestion, and misrepresentation provision extends beyond the incorrect use of the disclosure checkbox. It could also relate to a suggestion or representation regarding consultation, or some kind of agreement, with Māori and/or kaitiaki, that materially affected the grant of the patent – for example, if an applicant were to suggest that a greater degree of consultation took place than actually did, or were to suggest Māori or kaitiaki have given their permission or agreement when they have not, or that certain benefits were to flow to Māori when they will not. Such behaviors could be false suggestions or misrepresentations that materially affected the grant either because the PMAC might rely on those suggestions or representations to advise that the commercial exploitation would not be contrary to Māori values, or because they affect the context in which the Commissioner considers that advice. A false suggestion or misrepresentation is particularly relevant here, especially given that the test is not a strict “but for” test. The claimant does not need to prove that the Commissioner would have refused the grant but for the misrepresentation. It is sufficient to show that the misrepresentation had a material influence on the decision to grant.

The WIPO GRATK Treaty

Placing limits on domestic law

The foregoing establishes that IPONZ practice has a checkbox for disclosure on its patent applications, and there are existing repercussions in the law for fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation that materially affected the grant, which can relate to any interactions made (or not made, such as not being candid) during the patent prosecution process. Furthermore, the likelihood that not checking the checkbox correctly could materially affect the grant is significant in Aotearoa New Zealand due to the role of the PMAC and how its advice is to be considered by the Commissioner. Signing and ratifying the GRATK Treaty would significantly change this. This is because of the maximum standard that the treaty sets for remedies or sanctions in the event of a failure to disclose. As outlined in the foregoing, contracting parties may only allow for remedies or sanctions in cases of fraud. Contracting parties must “provide an opportunity to rectify a failure to disclose the information” unless there has been “fraudulent conduct or intent.”Footnote 114 Post-grant, contracting parties may not “revoke, invalidate or render unenforceable the conferred patent rights,” except where there was “fraudulent intent in regard to the disclosure requirement.”Footnote 115 Yet Aotearoa New Zealand allows for opposition, reexamination, and revocation on the basis of false suggestion and misrepresentation, as well as fraud. Opportunities to rectify failures under the Patents Act 2013 are limited and primarily arise either pre-grant in response to opposition proceedings or pre- or post-grant following reexamination.Footnote 116

If Aotearoa New Zealand were to sign and ratify the GRATK Treaty, it would likely have to amend its law so that failure to disclose the source of genetic resources and related TK (per the GRATK Treaty) can only found a successful opposition, reexamination resulting in revocation, or other revocation if the failure constituted fraud. Regarding pre-grant opposition or reexamination, anything less than fraud (including false suggestion and misrepresentation) could only result in the opportunity to rectify the failure. Regarding post-grant reexamination or revocation, false suggestion and misrepresentation in relation to the disclosure could not be the basis of revocation, even if the false suggestion or misrepresentation had a material effect on the grant. If the legislature were to leave “fraud, false suggestion and misrepresentation” for all other non-GR/TK disclosure related interactions with the patent office, there could be different outcomes resulting from a lack of good faith or lack of candor depending on whether it related to the disclosure or another interaction with the patent office. In other words, patent applicants (their attorneys/agents) would get away with more negative behavior (so long that it does not constitute fraud) in relation to the GR/TK disclosure than they would with any other interaction with the patent office; they would be given the opportunity to rectify in situations where rectification is not provided for other failings. Post-grant, it is unclear what the purpose of rectifying would be if it could not affect validity or enforceability. Perhaps the failure in disclosure (i.e., patentee or patent attorney/agent behavior) could not directly affect validity or enforceability, however, the information provided in the rectification could be used in standard revocation proceedings for non-novelty or obviousness, for example.

Notably, the GRATK Treaty says nothing about what the fraud has to cause in order for there to be invalidation. Unlike under existing Aotearoa New Zealand law, the fraud need not materially affect the grant of the patent. This means that it is possible that any fraud in relation to the disclosure could result in a successful opposition or revocation, whereas only fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation in relation to any other interaction with the patent office that materially affects the grant could result in a successful opposition or revocation. That said, as the GRATK Treaty’s provision on remedies and sanctions sets a maximum standard, it would be possible to implement it more leniently, so that the fraud has to materially affect the grant for there to be a successful opposition or revocation. At the same time, one could see it as logical to distinguish between fraud and false suggestion/misrepresentation in this way; as fraud is a more significant form of misconduct, perhaps there need not be any consequence for there to be no grant or revocation/invalidation.

In light of the foregoing, we argue that Aotearoa New Zealand should not implement the GRATK Treaty. Aotearoa New Zealand’s law and practice already exhibit means to implement disclosure obligations and determine what happens to the disclosure and what could happen for failure to disclose in good faith. Signing and ratifying the GRATK Treaty – with the maximum standard set out in its remedies and sanctions provision – would place restrictions on this.

Developing Aotearoa New Zealand law and practice

While we have argued that Aotearoa New Zealand should not sign the GRATK Treaty, this is not to say that the jurisdiction could not improve its law and practice. This could include learning from the negotiations around the GRATK Treaty. At the time of writing, the Patents Act 2013 was already over a decade old. Though seen as avant garde at the time of its passing, the Patents Act 2013 could now be viewed as limited because it only addresses “indigenous plants or animals.” It does not include other life forms, such as bacteria, fungi, or viruses. In contrast, the GRATK Treaty defines “genetic material” broadly as “any material of plant, animal, microbial or other origin containing functional units of heredity.”Footnote 117 That said, recall that the Patents Act 2013 leaves significant latitude to the PMAC to create guidelines and advise the Commissioner beyond the remit outlined in the Patents Act 2013. Note also the application discussed in the foregoing pertaining to a bacterial strain that was forwarded to the PMAC for advice. Furthermore, the Commissioner assesses the advice of the Committee when assessing the public order/morality provision, which is broadly drafted. Thus, the Committee could be (and has been) broader in its advice (beyond its stipulated functions), and the Commissioner could be broader on the advice they consider. The disclosure checkbox could be worded to be consistent with this.

It is worth noting that the IPONZ checkbox specifies that it is “New Zealand” indigenous species that are of interest. This adds clarity for patent applicants and arguably reflects the intent of the legislature, which used the term “indigenous plants and animals” to address Māori concerns and define a function of the PMAC. In other words, the purpose of the provision was to address Māori concerns such that “indigenous” must relate to Aotearoa New Zealand. However, this is limiting as there are species that are taonga to Māori because they were brought over in the Māori migration to New Zealand. They are not indigenous to New Zealand and so would not be included.Footnote 118 In contrast, the GRATK Treaty applies to “the country of origin of the genetic resources” or, where this is not known, the “source of genetic resources” (see Table 1), which is widely defined as:

Refer[ring] to any source from which the applicant has obtained the genetic resources, such as a research center, gene bank, Indigenous Peoples and local communities, the Multilateral System of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA), or any other ex situ collection or depository of genetic resources.Footnote 119

Table 1. Comparison of wording of Aotearoa New Zealand law and practice and GRATK Treaty

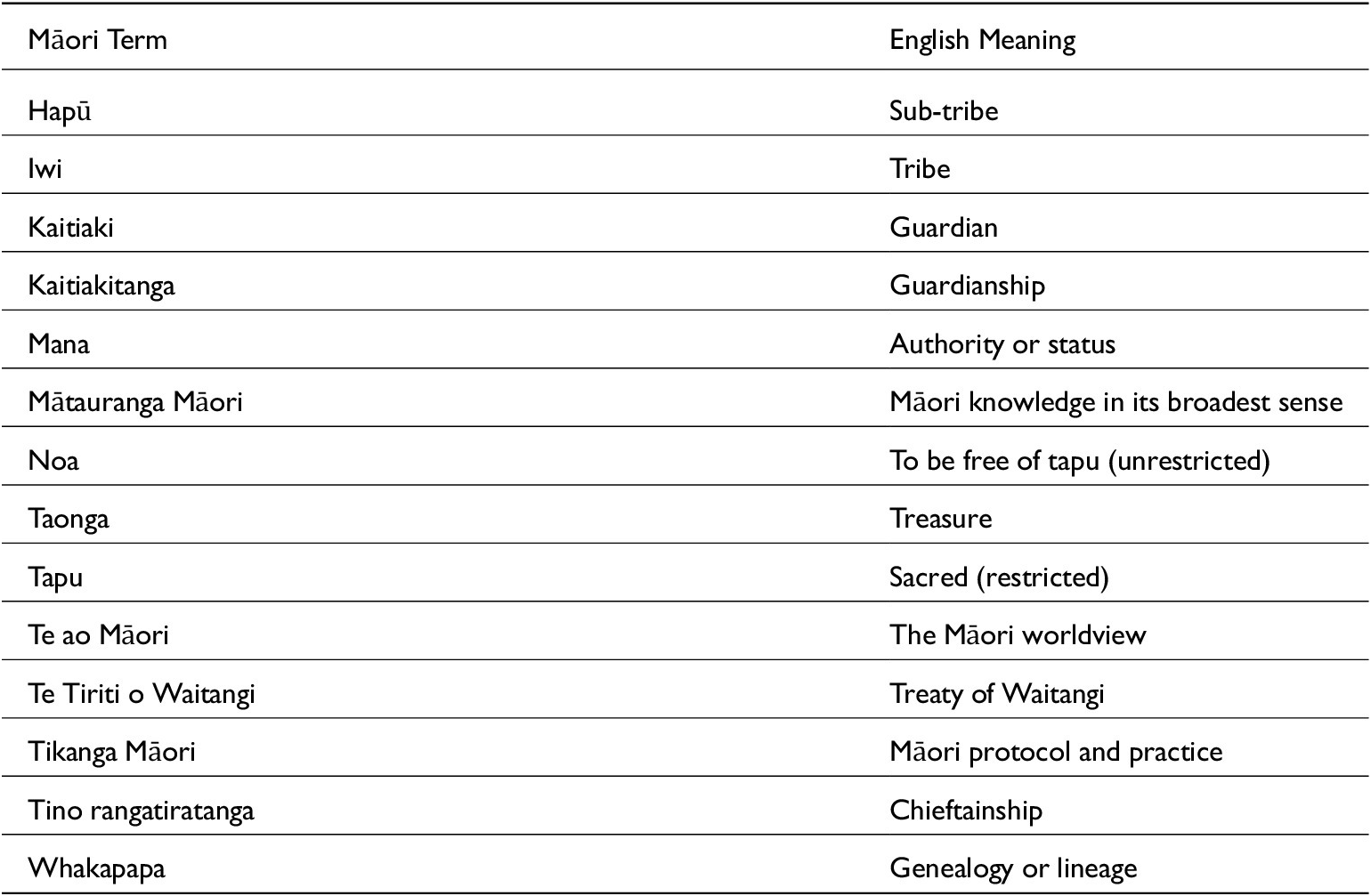

Table 2. Glossary of Māori TermsFootnote 129

Thus, disclosing the source of GRs per the GRATK Treaty is not jurisdictionally limited. If Aotearoa New Zealand were to implement a broader understanding of sources to be disclosed, this could provide more scope to PMAC. It could also allow the patent office to better address the concerns of non-Māori indigenous peoples and local communities.

A significant limitation of the Patents Act 2013 is that it only addresses Māori TK. This reflects its legislative purpose but could be broadened. The GRATK Treaty requires disclosure of the Indigenous peoples or local community “who provided the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources” or, where this is not known or not relevant, “the source of the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources.” The “[s]ource of traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources” is widely defined as:

any source from which the applicant has obtained the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources, such as scientific literature, publicly accessible databases, patent applications and patent publications.Footnote 120

Widening the knowledge sources of concern would be more consistent with the “fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation” provision, which is not tied to specific peoples. Put another way, broadening the text of the checkbox and what must be disclosed would be consistent with the fact that anyone can seek opposition/revocation via the “fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation” provision. Of course, not having a specific advisory committee might make it harder to show that a failure to disclose materially affected the decision to grant, but it would still be possible. For example, not disclosing the use of knowledge from a Canadian First Nation might result in IPONZ not finding relevant sources of prior art that would have rendered the claimed invention not novel or obvious, such that the failure to disclose materially affected the grant.

One way that Aotearoa New Zealand’s law and practice is broader than the GRATK Treaty is that it applies to all Māori “traditional knowledge,” whereas the GRATK Treaty disclosure requirement only applies to GRs and TK associated with GRs (see Table 1). That is, under the GRATK, contracting parties would not have to implement the disclosure requirement more broadly to TK not related to GRs. Note, however, that the substantive provision (Article 3), unlike the provision on remedies and sanctions (Article 5), is a minimum standard. Contracting parties may require more disclosure than that stipulated in the GRATK Treaty.

The GRATK Treaty stipulates that, if the applicant does not know the information they are required to disclose, “each Contracting Party shall require the applicant to make a declaration to that effect, affirming that the content of the declaration is true and correct to the best knowledge of the applicant.”Footnote 121 Aotearoa New Zealand could similarly require applicants to sign such a declaration if they do not know the information that the IPONZ patent application requires. However, as argued in the foregoing, we do not view this as necessary, as Aotearoa New Zealand law means that interactions between applicants (and their attorneys/agents) and IPONZ must not constitute fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation, which can be grounded in a lack of good faith or candor with the patent office. Of course, implementing such a declaration requirement could be used as a way to reinforce the obligations of applicants and their advisors. Furthermore, the advantage of mandatory requirements (as opposed to uncertainty or choice in application forms and declarations) is that it would be simpler to maintain that a false declaration or representation materially affected the grant, as it was not “a false declaration that the declarant need not have made.”Footnote 122

We add that, because the IPONZ checkbox and the GRATK disclosure requirements are based on subjective knowledge,Footnote 123 more than the disclosure is required to assist the patent office and the PMAC in determining derivation and values/morality/public order. Thus, the idea of voluntary databases or registries of mātauranga Māori and kaitiaki relationships has been floating around for many years with the objective of providing a source of information available for the purposes of examination.Footnote 124 They remain controversial due to mistrust in the Crown to oversee such a database, a lack of clarity around how exactly such a registry would function, and the potential to create friction within and between Māori iwi, hapū, and kaitiaki.Footnote 125

Finally, the GRATK Treaty’s provision on the possibility to rectify failures to disclose correctly (discussed in the foregoing) implies that it is possible that a patent office could deal with failure to disclose (whether fraudulent or not) outside of an opposition, reexamination, or revocation proceeding. That is, it does not rely on a third party bringing a relevant claim. In contradistinction, Aotearoa New Zealand’s “fraud, false suggestion, or a misrepresentation” provision is not a ground for rejecting a patent application during its initial examination; only for opposition, reexamination, or revocation.Footnote 126 Aotearoa New Zealand’s patent law could be amended to allow for rejecting an application on the basis of fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation due to the requirement of candor and good faith in interactions with the patent office.

Concluding thoughts

Elsewhere, we suggested that the adoption of the GRATK Treaty should not be over-celebrated, as it introduces only a very minor step in the right direction, with further work required to establish positive rights to protect TK and Indigenous knowledge systems more broadly. Herein we argue that Aotearoa New Zealand does not require the step offered by the GRATK Treaty as its domestic laws and practices arguably already offer better mechanisms. The law and practice in Aotearoa New Zealand already have what IPONZ refers to as a TK checkbox (though disclosure is not statutorily required), and case law states that a patent applicant’s lack of candor or good faith in interactions with a patent office can constitute false suggestion or misrepresentation. The provision on fraud, false suggestion, and misrepresentation applies to all interactions, regardless of whether they relate to statutorily required information or not. Furthermore, signing and ratifying the treaty would remove flexibility regarding sanctions and remedies. Existing law allows one to oppose, reexamine, or revoke a grant on the basis of fraud, false suggestion, or misrepresentation. The GRATK is narrower, allowing only opposition, reexamination, or revocation (though it also allows for rejection) on the basis of incorrect disclosure if there is fraud.

As argued in this article, Aotearoa New Zealand’s law and practice are not perfect, but improving these is not contingent upon signing the GRATK Treaty. It is also worth noting that, because the GRATK Treaty does not grant any rights but is purely administrative, there is no international benefit to becoming a contracting party. That is, Māori would not gain any benefit overseas, as there are no rights to be mutually recognized, for example.

We cautioned elsewhere that there was the danger that over-celebration of the GRATK Treaty could generate the belief that Indigenous peoples have gained protection and nothing further is required.Footnote 127 We note here that this kind of positioning has started to appear in the WIPO IGC negotiations on treaties to protect TK and TCEs.Footnote 128 In the 51st session in May/June 2025, only a year after the GRATK Treaty was adopted, in discussions around the mandate for the next biennium, industrialized member states and groupings opposed work on GRs being in the first paragraph of the mandate because of the conclusion of the GRATK Treaty. This did not include Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, who expressed opposing opinions more in line with China and the Global South, who – consistent with the Indigenous Caucus – insisted that GRs had to continue to be part of the mandate because they were inextricably tied to TK and TCEs, and because the GRATK did not relateFootnote to rights but was purely administrative, so GRs had to remain part of the mandate to achieve rights in relation to GRs. Yet many industrialized member states insisted that the work on GRs was complete, resulting in the addition of language to clearly state that no normative work on GRs would be undertaken in the next biennium.

While Aotearoa New Zealand, and any other member states concerned with their Indigenous peoples, must partake in the WIPO IGC in the hope of shaping any agreements that come from it, the analysis in this article underscores that it must not be beholden to international fora and negotiations. International law and the law and practice beyond Aotearoa New Zealand affect Māori interests and all patent applicants from Aotearoa New Zealand. However, this should not restrict Aotearoa New Zealand addressing Māori interests in domestic law. As our foregoing analysis of the GRATK Treaty illustrates, doing so could result in waiting over 20 years to end up with something less than what a member state can easily achieve domestically. The continuing negotiations for TK and TCEs potentially differ from the GRATK Treaty in that they might result in sui generis rights (though certain member states and groupings, such as the United States and the European Union, take the position that a nonbinding measures-based approach is preferable). The idea of such an agreement coming out of a UN body is appealing, but it should not stop the government of Aotearoa New Zealand from looking inward, because looking outward might be distracting and disappointing.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to the New Zealand Royal Society Te Apārangi for supporting this research.

Funding statement

This work was undertaken with the support of the New Zealand Royal Society Te Apārangi (Grant No. E4223; Award No. 4315).

Declaration of conflicting interest

N/A