Americans come, there is bread and freedom; Soviets come, there is bread but no freedom; Communists come, there is no bread, no freedom.

A noble child is completely fed and raised on American products. From the moment when he is born, assisted by a midwife wearing American-made gloves, to his death, he does not need to eat a grain of rice grown by Chinese farmers, nor wear a piece of cloth woven by Chinese peasants. What he eats are imported milk powder, fish oil, vitamin ABCD, and all kinds of canned food. What he dons are foreign wool sweaters, suits, and jackets.

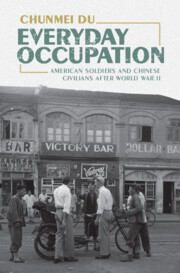

As exemplified by the first epigraph often attributed to Hu Shi – though likely by mistake – pro-American elites echoed the views of the acclaimed leader of Chinese liberalism, lauding the country’s material progress and postwar aid to China, along with its political and economic systems. At the same time, leftists warned against the pervasive American influence on Chinese everyday life, like the cautionary tale told by Shanghai’s Xinmin Evening News. Regardless of one’s attitude, American products (Meihuo) remained a key component of Chinese urban residents’ memories of the end of WWII. That moment began with the unforgettable scenes of GIs and Nationalist elite units parading in victory, clad in American khakis, leather shoes, weapons, and equipment, through the streets of jubilantly crowded, newly liberated cities. Soon afterwards, American commodities filled up window displays in fancy shops and tens of thousands of street stands: Quaker oatmeal, Listerine toothpaste, Camel cigarettes, American oranges, chocolate, instant coffee, milk powder, ice cream mix, and peanut butter, as well as colorful English-language pictorials depicting American defeats of the Japanese in heroic battles.3 Everything was for sale and on sale. The American “spiritual aid” also went hand in hand with this material aid.4 Hollywood movies banned for decades in Japanese-occupied areas made a full comeback with huge advertisements and posters everywhere, and Shanghai imported nearly two thousand new American films.5 Popular magazines such as West Wind brought every facet of the American culture to the households of middle- and upper-class urbanites, housewives, and youth, emphasizing its quotidian and trivial practices. John King Fairbank, the new director of the US Information Service and later a founding figure of China studies in the United States, observed that “reoccupied China was intellectually starved for much of what we had to offer … the need for information seemed to me just as urgent as the material supplies being brought in by UNRRA.”6

In 1946, a Shanghai reporter identified five major sources for the “ubiquitous invasion of American goods”: first, those obtained with proper procedures; second, surplus goods distributed as relief or sold on the market; third, smuggled products; fourth, black-market goods from American soldiers through scalpers; and fifth, items from Jews, who sold their own quotas or counterfeits.7 Average citizens received free items from UNRRA and bought surplus war supplies at reduced prices from government or agency distributers as well as on the rampant black market. For some, encountering American products was like a “reunion with an old lover” who had departed after Pearl Harbor.8 But for many more, these goods were a necessity during a time of material shortage and high inflation, or an absolute novelty that had only been a privilege for the wealthy. As one author described it, “while dignitaries enjoyed their cocktail parties, ordinary people could eat American canned food to quench their cravings.”9 In comparison to Jeeps and Jeep girls, goods became the most prevalent encounter with America for both Chinese elites and commoners, offering a bittersweet experience of victory, survival, prosperity, and despair.

American military and economic aid to China played a crucial role in China’s war against Japan and was equally crucial in its postwar reconstruction. After the war, lend-lease aid continued in China, reaching another US$781 million, while UNRRA distributed massive quantities of war surplus supplies.10 Scholars today continue to debate over the exact nature and scale of the actual American aid to China, as well as its impacts on China’s national economy and the outcome of the civil war. Most focus on the military supplies gifted or sold to China, ranging from arms and munitions to heavy equipment and industrial goods.11 While these questions remain crucial to our understanding of the civil war period, this chapter shifts the focus from battlefields to the territory of urban residents’ households, city warehouses, street stands, and deep valleys, linking the macrohistory of national and global politics to the microhistory of civilian daily lives. It delves into how American goods influenced the Chinese experience and perceptions of the country by highlighting entangled objects within the context of Sino-US relations. Rather than narrowly defined military supplies, my focus lies on the everyday products that had a prominent presence in Chinese lives and fueled debates. In the eyes of Chinese consumers and critics, household items like canned food, coffee, Coca-Cola, DDT, and penicillin, which will be explored in detail later, were all associated with the American military – whether originating from wartime military inventions, acquired from the surplus sales and UNRRA relief efforts, introduced or sold by US soldiers, or distributed and guarded by them.

In the postwar era, American goods reached all echelons of society, from elites to the destitute, affecting rickshaw pullers who began their days with instant coffee, Jeep girls who flaunted the latest fashions, street vendors who dealt with legal and illegal merchandise, young thieves and local gangs who frequently pilfered from US military warehouses, farmers who saw their fields sprayed with DDT, owners of local businesses who competed with imported products, and tens of thousands of residents who consumed or rejected American wheat, flour, and rice. As a result, American products became a familiar experience, as a necessity, a popular commodity, and a cultural spectacle that influenced Chinese consumption, tastes, and views. Some locals were drawn closer to the “Beautiful Country” (Mei guo), while others were alarmed by the risks of “Americanization” (Mei hua), fearing the impacts of its material and spiritual aid to Chinese industry, society, and morality.12

The influx of foreign industrial goods created significant difficulties for local businesses, engendering fears of capitalism crushing the Chinese economy. Riding the tide of the National Goods Movement, the Communists orchestrated anti-American boycotts as a strategic measure to mobilize urban populations in their wider struggle against the Nationalist Government. However, the movement turned out far less successful than the one triggered by the Peking rape incident. In the end, it was the US military’s mishandling of goods-related matters that lent the Communists a more compelling and unifying narrative in their opposition against US imperialism. The military’s stringent policies against theft and black-market activities made everyday encounters with American goods increasingly dangerous and sometimes fatal. Its “halt or shoot” policy, implemented to protect US properties, led to frequent civilian deaths, followed by a series of legal disputes and political frustrations as Nationalist officials lodged complaints and protests to no avail. These incidents became another major source of Chinese grievance, alongside traffic accidents and sexual relations. Together, the three signature causes, serving as rallying points, coalesced into a powerful campaign led by the Communist Party against American brutalities.

Bitter Sweet: Tastes of America

Not poetic or romantic, but it [coffee] is a comfort for the masses.

She is sweet like Coca-Cola.

Food remained a vital aspect of daily life in postwar China, providing essential nutrients as well as new tastes. Thanks to rampant inflation, dislocations after years of brutal wars, and natural disasters, the era was known for major famines, a refugee crisis, and an economic breakdown. UNRRA carried out emergency food and medical relief in the famine areas of Hunan and Guangxi, levee repairs in the Pearl River delta and the Qiantang River of Zhejiang, and agricultural rehabilitation projects in Henan where the humming of Ford Ferguson and other imported tractors was replacing the centuries-old hand-plowing methods. Large quantities of staple foodstuffs such as flour, wheat, and rice poured into the cities of Beijing, Guangzhou, Nanjing, Shanghai, and Tianjin. Relief food was not only essential for starving peasants, urban refugees, and the unemployed, but also important for civil servants, office workers, teachers, and students who had a higher social status and yet remained economically vulnerable. During his grueling return trip from the southwest back to his former campus in Beijing, a Tsinghua University student was thrilled to receive a five-pound can of milk powder and a five-pound can of bacon. This moment of relief came just before he and his peers boarded empty coal ships heading north from Shanghai. Similarly, another student from Wuhan University developed a fondness for two new favorites: ice cream mix and Klim, a brand of powdered milk initially adopted as part of the US Army ration – Klim being the word milk spelled in reverse. Even decades later, he remembered them as a “delicious snack and superior nourishment after years of malnutrition.”15 In his memoir, English writer J. G. Ballard recalled his experience of the Japanese surrender in Shanghai. On that hot August day in 1945, the teenager watched from the roof of the Japanese prison, where he had been interned for more than two years, as parachutes descended from the bomb doors of a B-29, dropping a line of canisters carrying American relief supplies. The “cargo of treasures” included “tins of Spam and Klim, cartons of Lucky Strike cigarettes, cans of jam and huge bars of chocolate.”16

Chinese journals introduced a garden variety of nutritious American surplus combat food packages, especially the popular canned food. The C ration pack contained beef stew, pork and beans, and meat hash, plus biscuits, coffee, and sugar. The K ration for soldiers on the front line provided three meals of three thousand calories in total – with veal for breakfast, Spam for lunch, and dried sausage for dinner, in addition to a fruit bar, crackers, cheese, a bouillon cube, malt-dextrose tablets, and a packet of lemon crystals, chewing gum, cigarettes, toilet paper, soap, and water purification tablets. The additional “Ten-in-One” provided more varieties including more types of canned meat, dehydrated potatoes, onion and vegetable soups, and dried milk. The B ration for field kitchens aimed to include three different sorts of meat, four vegetables, a dessert, and canned fruit or fruit juice in the five pounds of food allocated to each man for a day.17 After sampling these rations, Chinese customers often shared their exhilarating experiences. Many could not believe how huge American potatoes were, acknowledging that although these canned foods might not have been great by American standards, they tasted very delicious to those with hungry stomachs. One customer commented that canned turkey from the US cost the same as local fresh chicken, yet it was boneless and four times larger.18 Another noted that within a year following the victory, these imported provisions were everywhere, spreading “from the metropolis to the villages and from the wealthy to the poor.” Initially driven by curiosity, consumers now embraced these products partly for their cheaper prices.19

In addition to satisfying hunger, American food was a novelty to be seen, touched, smelled, and above all, tasted. One of the newly popularized products and tastes was coffee, also included in the ration meal. The US War Department considered coffee an essential element of the troops’ diet, as it provided a stimulus for their physical stamina and morale. The wartime demand further accelerated the development of instant coffee, such as the one by Nescafé. Describing his first impression of Shanghai, one college student wrote that he was so jealous of the local customers who could taste American coffee and milk, made fresh from powders on the street market.20 It was probably an exaggeration that all Shanghainese now loved to drink coffee with its strong taste, bitterness, aroma, and “romantic sentiment.”21 Overall, coffee was more of an acquired taste, a foreign one to begin with. The first known coffee was sold as “cough syrup” in a British drug store in Guangzhou several decades earlier.

But the unfamiliar bitter taste did not prevent the dark drink from becoming popular in China. Coffeehouses had been a familiar urban and cultural space since the second half of the nineteenth century for Western customers as well as an increasing number of affluent, middle-upper-class Chinese urban consumers. In the 1920s and 1930s, New Sensation School writers often wrote in Shanghai’s cafes and set many of their stories in similar, Western-style urban spaces, including coffeehouses, dance halls, and Western restaurants. Cafes were also known and projected as sites for romantic and sexual encounters with alluring waitresses and prostitutes.22 Due to material shortages, coffee consumption during wartime became restricted and even banned in Chongqing as a luxury product. After Japan’s surrender, the number of cafes quickly increased. From June to October 1946, for example, coffeehouses in Shanghai increased from about 50 to 186, not counting Western restaurants that also served coffee.23 Despite being associated with a Western style, China’s cafes in the 1940s also accommodated Chinese tastes by adding familiar entertainments such as music, dance, and even traditional Chinese operas. Local customers, mostly male, expected to be entertained.24 As one observer noted, coffeehouses in Shanghai became filled starting from 9:00 p.m., when customers sought a modern foreign experience after dinner and enjoyed watching traditional operas while drinking coffee served by showy waitresses.25 Many sites also served Chinese cuisines together with Western drinks and food. For the majority, the coffeehouse was a venue for entertainment and socializing rather than a public space intended to spark or spread revolutionary ideas.

A sudden and major change to Shanghai’s coffee culture occurred in the late 1940s when new open-air coffee shops (露天咖啡館) and coffee stands (咖啡攤) sprang up on every street and corner like mushrooms after a rain (see Figures 5.1 and 5.2). As one journalist from The China Weekly Review put it, China’s masses discovered coffee in the year 1946: “Once sipped only by the well-to-do, coffee today delivers its exhilarating ‘lift’ to the laboring classes; to the ricksha coolie, pedicab man, domestic servant, and even occasionally to the lowly beggar out to celebrate a bumper crop of alms.”26 In the morning, these brand-new wooden coffee and toast stands, equipped with stools or chairs, served Maxwell House coffee with Carnation milk to tram drivers, conductors, and other early risers. Within three minutes, hot breakfasts with food and coffee were served, as customers washed down their set meals and quickly vacated their seats. During summer, it was common to spot “a perspiring pedicab or ricksha coolie halt” to down two or three glassfuls of iced coffee served in plastic glasses. On a hot day, one sidewalk merchant sold more than one hundred glasses of iced coffee in thirty-five minutes, not including the two unpaid glassfuls, given for “the price of his silence,” to the policeman on the corner who came over. Although the coffee tasted weak and iced coffee was even more feeble, these affordable coffee stands were so popular that they could be found on “virtually every busy street corner and on the sidewalks of lesser roads.”27 Due to their affordability and convenience, canned instant coffees became a new favorite among the working class, even winning over the coolie customers who traditionally sought tea in street stands or low-cost teahouses. American-style snack stands that sold milk, coffee, hot chocolate, and bread with butter were also said to be winning the street competition over the traditional Shanghai-style breakfast featuring beef noodles and sticky rice balls.28

Figure 5.1Long description

Under the caption, a rickshaw man sits on his rickshaw at the right, while a female coffee vendor squats on the left, a pot of coffee placed in front of her. They are exchanging money for a cup of coffee, both appearing spirited and happy.

Figure 5.2 Drawing of an outdoor coffee stand in Shanghai, 1946. Guoji xinwen huabao.

Figure 5.2Long description

One customer wears a Western suit, while the other is dressed in a Chinese workman’s shirt. Both are seated on long stools, enjoying their coffee.

Coffee not only brought a novel taste to China, but also created a new social space. One sketch made of the new coffee stands emphasized the freedom unavailable in other fancy foreign restaurants, calling these stands the best at combining Western material and Eastern spirit.29 Another noted how these coffee stands were a place for everyone. Because of the minimal cost of this American drink, coffee became popular for all, even among coolies who could not have possibly ever “dreamed of enjoying American drinks every day!”30 In these new stalls, young office workers in suits and sweating rickshaw pullers sat next to each other, drinking coffee and having buttered toast. Thanks to the thousands of street stands, “the noble drink was brought to the street, and the philistines stormed the salon.”31 Lu Xun, a leading leftist writer, who famously mocked intellectuals for their lack of concern about the masses by saying that “I don’t drink coffee, and green tea is better,” could not have predicted the huge popularity of coffee among Shanghai’s working class after the war.32 Coffee finally fell off its sacred altar, turning from a luxurious foreign drink to a commonplace commodity. As one observer lamented, even this small amount of machine-produced goods from capitalist America had changed the lifestyle of the entire population of Shanghai residents and those beyond.33

Not everyone was a convert to coffee. After being offered a canteen cup of coffee by a marine officer in the field as a gesture of friendship, a Nationalist captain only sipped once and never asked for it again. But he became an instant devotee of Toddy, a chocolate drink, and enjoyed pogey bait, a term covering all types of sweets.34 Compared to the taste of coffee, sweetness appealed to a more universal palate. Like elsewhere in the world, a common scene of liberation included seeing children chasing after American Jeeps and trucks for candies and chewing gum. Chinese newspapers advertised Eskimo Toffee, frozen suckers, and brick ice cream as being “always safe” and able to “protect your children’s health.”35 But the most popular American “sweetheart” remained the classic Coca-Cola. During the war, American post exchange (PX) stores on military bases maintained a well-stocked supply of small treats – candies, cigarettes, and drinks – and were a powerful force in “establishing Coca-Cola as the archetypal American beverage.”36 Part of General Marshall’s troops welfare policy, these supplies of small luxuries were supposed to ensure soldiers had a little piece of home with them while living abroad. After the war, technicians from the Coca-Cola Company were sent to open plants across the world, including in occupied Germany and Japan, and the company monopolized soft drink markets for US servicemen. Through both veteran consumption and local emulations, “the sale of the drink to American soldiers acted as ‘the greatest sampling program in the history of the world,’” and as a result, “by 1950, Coca-Cola had become a preferred drink among veterans returning home as well as among European youths.”37

The American Armed Forces in China took the Coca-Cola supply seriously. In Qingdao, the US Navy Port Facilities contracted with the Laoshan Iltis Mineral Water Co., Ltd. to produce bottled Coca-Cola for their exclusive consumption.38 In Shanghai, urgent and imperative requests were repeatedly made to ensure the production of sufficient Coca-Cola. On May 15, 1946, Lieutenant Colonel Sylvio L. Bousquin, Adjutant General, Headquarters United States Army Forces in China, wrote to the Shanghai municipal government to request extended time for the electricity supply of the Far Eastern Import and Export Company that produced CO2 gas. He stated the “imperative requirements” for CO2 gas, at 230 kilograms daily, as “failure to obtain this gas will jeopardize 38,000 barrels of Coca Cola Syrup which is now in United States Army stocks.” On May 17, they made another request for electricity, this time to increase the allotment for their warehouse electricity consumption limit to 90,000 KWH per month for cold storage protection of perishable food stocks due to the anticipated hot weather in the next few months. Such exception should be made, they argued, despite the electricity shortage in the city and existing restrictions, “due to the fact that our mission in Shanghai is a non-profit making one, but one solely and exclusively for the assistance of the Chinese government, and at the invitation of the Chinese government.”39 As we have seen, the US military expected special privileges, and similar arguments were made in many other situations, such as seeking exemptions from taxes on food, drinks, and hotel stays, as well as waivers for water bills for their residences.

For commercial use after the war, Watson’s Mineral Water Company, the licensed bottler in Shanghai, produced Coca-Cola by mixing imported concentrate with carbonated water, using powerful bottling machinery also imported from the United States. In fact, the magic drink was not an immediate hit when it first arrived in China in the early twentieth century. Most people found its phosphoric acid taste strange, resembling a Chinese fever syrup. Sales were not even as successful as for its British or Chinese counterparts due to Coca-Cola’s shorter history in China and price disadvantage compared to local soft drinks.40 The business was subsequently closed during the Japanese occupation. However, when it reopened after the war, Watson’s Coca-Cola had a completely new life. It launched a successful marketing campaign including huge billboards that lined the streets, as well as posters, calendars, and flyers everywhere, often paired with female celebrities. More importantly, like elsewhere around the world, GIs became a moving advertisement for the cool American drink as they were seen drinking Coca-Cola everywhere and all the time, in real life and in representational space.

In wartime advertisements, Coca-Cola was frequently portrayed as “a symbol of good will” shared among allies. The message was conveyed through imagery that featured Chinese officers drinking Coca-Cola alongside American pilots, evoking a sense of camaraderie by appealing to the successful operations of the “Flying Tigers” over the hump.41 After the war, Coca-Cola continued to shine as a global commodity, serving not only to quench thirsts and refresh minds, but also as a cultural symbol to bridge differences and bring peace, freedom, and democracy to the world. Just as some Chinese soldiers tried to emulate the lifestyle of the American allies, so did civilian populations. By the late 1940s, Coca-Cola, with its new postwar prestige and availability, had become the best-selling beverage in Shanghai, defeating competing Chinese carbonated drinks as well as beer and orange juice. Demand was so high that Watson had to increase its production to two hundred and forty thousand bottles a day, and by 1948, Shanghai became the first foreign market to exceed annual sales of more than 1 million cases.42 As one critic explained, the surging popularity of the “tart Coca-Cola” after the war, while “no one could explain why it was so attractive,” had to do with the Chinese worship of the Allies – that is, it was a transfer of admiration of the country to the drink.43

Like Coca-Cola and coffee, US goods became both cheaper and tastier to the Chinese after the war, thanks to sales of surplus supplies and America’s rising global prestige (see Figure 5.3).44 An encounter with American food involved a variety of experiences ranging from a sense of curiosity and anticipation in figuring out how to open a can of surplus food to the thrill of discovering supersized potatoes and boneless turkey and the fizz of drinking cold Coca-Cola on a hot summer day. After receiving compressed biscuits and two oversized woolen coats distributed by UNRRA in 1946, two siblings in Shanghai wrote thank you letters to the American children who had donated them, remembering “our English greatly improved during that time.” Sometimes the excitement could be puzzling. One individual drank up a cup of coffee in one big gulp without knowing to add sugar; another was nervous about how much and what kind of water to mix with the milk and chocolate powder, at which temperature, and for how long.45 These new experiences took place at home where food was exchanged with families and friends, and in public in open-air food stands, coffeehouses, and Western restaurants, as well as in the representational space of newspaper columns, fiction, and plays as many recounted their personal encounters with American food. To watch and to be watched, tasting these novelties was as much about national prestige and socioeconomic status as about flavor, no matter whether the fare was bitter coffee, sweet Cola, or bittersweet America.

Figure 5.3 American canned food on window display in a Shanghai store, featuring a Coca-Cola poster on the outside wall, 1947.

Figure 5.3Long description

A Coca-Cola poster is visible on the outside left wall, while the top of the window is scribed with “Tung Tai, estimated 1899, Groceries, Wines, Tobacco, Sundries.”

The Fight Goes On: Chemical Weapons of Mass Consumption

In October 1945, National Geographic ushered in a new era with its feature article “Your New World of Tomorrow.” The piece extolled groundbreaking inventions poised to revolutionize health and medicine, shining a spotlight on two exceptional “wonder drugs” that emerged from wartime technological advancements: DDT and penicillin.46 During the war, the US military had effectively utilized DDT to control malaria, typhus, body lice, and plague. Following the conflict’s end, it quickly gained worldwide popularity as an essential pesticide, seamlessly integrating into the fabric of everyday life.47 Yet, far more than just another American product, DDT engendered a sense of national pride for its contributions to the double war against the Axis and mosquitos. Its promise of control, health, and prosperity positioned it not merely as a commodity but also as a cherished gift to the world during the crucial period of postwar reconstruction. Accompanying this narrative were pesticide commercials that employed a striking “shoot to kill” messaging, evoking a distinct militaristic undertone. This rhetoric mirrored the approach the United States took in its global initiatives, where the application of potent “weapons” against perceived threats – be they insects, microbes, or humans – showcased America’s technological, industrial, and military superiority and dominance in the postwar era.

Like elsewhere, DDT was widely used in China after WWII for insect and pest control. The American military often facilitated the application or requested its use (see Figure 5.4). In Tianjin, American military aircrafts targeted areas where reservoirs were concentrated.48 In Nanjing, Qingdao, Beijing, and Guangzhou, the American military provided assistance to the Nationalist Government by conducting multiple air spray operations that covered entire cities. Even Chiang Kai-shek’s residence in the capital received the attention of American medical officers who applied DDT for pest control.49 To promote the general use of DDT, a variety of Chinese scientific and popular journals enthusiastically introduced this novel chemical and its associated commercial products. They celebrated its remarkable benefits and versatility, as it could be applied to body, food, animals, bedsheets, and clothes. Hailing it as a “nuclear weapon against insects,” Chinese news, books, pamphlets, and advertisements eagerly showcased its prowess, often drawing upon the reputation of American military might. The battle against pests and diseases became another frontier where the extraordinary power of this “wonder drug” was trumpeted on the home front.

Figure 5.4 Weekly DDT spraying by a C-47 transport over US military accommodations in Shanghai, September 1946. Xinwen bao.

Despite DDT’s overwhelming official and media acclaim, when the Chinese had direct and close contacts with the new chemical product, its foggy sprays, strong smells, and massive reach also caused discomfort and concerns. Some asked, “Aren’t such indiscriminate attacks on enemy and friendly insects leading to the elimination of all?”50 Witnessing the air spray’s devastating effects on bees, one reader from Qingdao warned about DDT killing huge numbers of bees during their breeding season, and called to protect beneficial insects.51 In Nanjing, locals protested against imposed DDT treatments, especially the unrestricted spraying of all farmland and soil pits surrounding the US Army Advisory Group’s residence.52 The public already knew DDT’s toxicity. One cartoon depicts the mixed allure and danger of the chemical, portraying a Chinese man kneeling before a human-sized DDT bottle, while a thinly dressed woman leans against the bottle and holds a spray hose with her one arm and covers her eyes with the other. The begging man, now with chemical spray all over his face, appears to be in pain. In another cartoon, a young male dressed in a suit is swallowing a bottle of DDT, as a Westerner tries to stop him. The accompanying script reads: DDT has turned into a suicidal tool upon arriving in Shanghai.53 Overall, an encounter with DDT was a direct and physical experience for local residents. Whether watching military aircraft spraying across the city or individual soldiers delousing their houses, clothes, hair, armpits, and even their faces, this constituted an intimate contact with America through chemicals, science, and technology; spectacles of occupation; and civilization. Before boarding navy ships, US medical officers used DDT powder to delouse Chinese soldiers as well as the Japanese. Around the world, foreign children and families were profiled in news photographs, educational pamphlets, and advertisements, shown gratefully receiving a dousing of DDT powder spray from a uniformed American man, “evoking paternal notions of U.S. interests abroad.”54 Whether the recipient was grateful or not, the American servicemen were here to kill, control, and teach, all at once.

If DDT was dubbed the chemical to kill all germs, the other wonder drug, penicillin, held an esteemed reputation in China as the cure for all diseases. Discovered by a British scientist in 1928, penicillin was introduced as a therapeutic agent by American scientists in 1942. As part of the war effort in response to Japanese biological warfare, penicillin was only manufactured on a small scale and monopolized by the armed forces to treat injured soldiers. While it cured many bacterial diseases during the war, including otherwise fatal battle wounds, it gained particular acclaim for its sensational results for curing syphilis. After the war, the “wonder bullet” was put into mass production for commercial and civilian use. It quickly became a major export to the world, representing both a potent American “weapon” that helped win the war and a miracle drug that could now cure everyone.55

Penicillin, known in Chinese as qingmeisu (青霉素), pannixilin (盤尼西林), and peinixilin (配尼西林), was first introduced in professional journals in the early 1940s. But it was not until the middle of the decade that it became widely known to the general public. In June 1944, Vice President Henry Wallace travelled to Chongqing, becoming the highest-ranking American official to visit modern China. During his visit, Wallace conveyed personal messages from President Roosevelt to Chiang Kai-shek and also presented a gift of penicillin.56 Together with this historic visit, the new drug appeared in major Chinese news reports. Its status as an official American gift added diplomatic and political prestige to this groundbreaking medicine. The first sample drugs arrived in August of that year, thanks to the Lend-Lease Act.57 Sensational stories added to the allure of the new American drug. One popular tale recounted how Tojo Hideki, the former Japanese prime minister who had shot himself in the chest, quickly recovered after receiving penicillin injections, enabling him to stand trial.58 Chinese scientific, medical, health, and educational magazines introduced penicillin’s powerful effect and versatility to a variety of children, youth, and general readers. It was almost universally celebrated as a savior for humankind, a “legendary” or “sacred medicine.”59

Penicillin’s reputation was so powerful that it became a political metaphor for democracy among leftist critics, transforming this panacea for diseases into a remedy for China’s political ills. On October 10, 1944, the national day of the Republic of China, Tao Xingzhi, a prominent educator and former student of John Dewey at Columbia University, wrote a poem calling for “true democracy” as the “political penicillin” to eradicate all political germs. He emphasized that while the medical penicillin brought by Vice President Wallace was commendable, it alone could not save the entire population.60 Less than a month later, Tao presented Jian Bozan, a Marxist scholar educated at the University of California, with a gift of Camel cigarettes, symbolizing a “cure-all elixir” from Roosevelt’s country, with the hope that it would “puff out the political penicillin” ignited by the eminent historian’s wisdom.61 After the high-stakes 1945 Chongqing Negotiations, Chairman Zhang Lan of the China Democratic League bid farewell to Mao Zedong at the airport and once again employed the metaphor when responding to a journalist’s inquiry about the objectives of the marines’ landing, which was taking place in North China. While welcoming the Americans’ contribution to disarming the Japanese forces, he also expressed the desire for their increased support of Chinese democracy, stressing that “‘democracy’ is the political ‘penicillin’ that can cure China’s long ills.”62

Due to its high demand, imported and black-market penicillin coexisted with surplus distributions and government purchases. Said to be another type of gold for its universal status and enduring value, penicillin was sought after by stocking merchants and black marketeers. Sales and demand were further boosted by commercials, which appeared in major newspapers such as Shen bao, promoting the various imported and local products, including injections, creams, new types of treatments, and even odd products like penicillin ice cream and gum. Although its most common clinical uses in Chinese hospitals were treating pneumonia, meningitis, and other serious infections, advertisements primarily targeted venereal diseases, especially gonorrhea and syphilis. On the postwar black market for American military supplies, penicillin was frequently spotted next to condoms and pro-kits.

As in the Nationalist areas, penicillin was well received among the Communists headquartered in Yan’an. Their initial exposure to this American drug came through the Dixie Mission. An American physician within the United States Army Observation Group used penicillin to treat not only his own team members but also some Communists in need. In the words of one Chinese observer, “Penicillin, Hollywood movies, and General Patrick Hurley represented American science and technology, culture, and politics respectively,” and more broadly, the “Army Observation Group became a window through which Yan’an learned about the outside world.”63 Members of the propaganda department frequented the American group to collect English publications. Some of the hosts began wearing American military boots and using DDT for mosquito control; learned how to drive a Jeep and perform mechanical repairs; and had their first tastes of Coca-Cola, gum, American alcohol, chocolate, cigarettes, and canned tomato beans. Yang Shangkun, a CCP leader who later became the fourth president of the People’s Republic of China, was said to have three passions: Mao Zedong, his wife, and American cigarettes – the latter being “his only vice,” which he consumed in monstrous proportions.64 Before the Observation Group’s departure, their Jeeps were packed with the famous Yan’an wool rugs featuring animal patterns, their favorite souvenir. They also left the Communists with plenty of gifts, including penicillin, Jeeps, portable radio stations, hand-cranked generators, and transmitters, all of which were put to good use in the fight against the Chiang Kai-shek regime.65 Building on American-gifted mold, the first Communist production of penicillium was attributed in 1945 to Richard Frey, an Austrian physician and foreign member of the CCP. Toward the end of the fierce civil war, Communists also fought to secure greater access to UNRRA goods in their occupied areas, including the precious penicillin.66

American Goods versus National Goods

American goods, though not a panacea for all of life’s ills, were a highly desirable part of Chinese daily life, sought after by tens of thousands residing on the coast and in the hinterland. While American commodities had been present in China for more than a century and a half, it was only in the late 1940s that commoners and the poor had direct access to these products and experiences, sparking the phenomenon of “American obsessions.” These goods formed the American world that directly affected their lives and views of a country that had been too remote to reach. It was also through these iconic and everyday items, together with GIs who visibly consumed, represented, and advertised them, that Chinese society at large saw, felt, and understood the American military presence.

Food stood at the frontline of the debate over American goods as it concerned both the individual body and the national strength on biological, cultural, and psychological levels. Those who had worked for the American military frequently discussed food in conjunction with US soldiers’ bodies.68 One Chinese college student who had done office work highlighted the American menu, which included a high-calorie diet of eggs, vitamins, and unlimited supplies of butter, bread, and coffee. He pointed out that in order to understand Americans’ superior fighting power and emotions, in their work and in their sex drive, one had to understand that they had larger bodies, a result of what they ate.69 Huang Shang, once an interpreter for the Allies, also commented on how American food and bodies were much bigger. He couldn’t believe how huge their potatoes were and observed that the enormous physical contrast between American and Chinese soldiers was between one who was well fed and well dressed, and the other who was small, malnourished, and “all emaciated.” Calling the American Service of Supplies a “fairy treasure chest” filled with everything anyone could want, Huang also commented that this “gigantic and complex organization” was “a miniature of the American Dollar culture” that spread to every corner, from “peach, apricot, beef, ham, to women’s legs on Broadway.” He argued that without their supply system, “American soldiers could not even fight.” In another more exaggerated version attributed to General Chen Cheng, the top Nationalist military commander remarked, “American soldiers cannot fight without coffee,” thus highlighting the superior spirit of Chinese troops who, though only sustained by rice porridge, could still fight courageously.70

For the Nationalist Government, there was an awkward discomfort in admitting American generosity and superiority and preserving individual and national dignity. Whether during wartime collaboration or postwar reconstruction, Chinese elites tried to maintain a subtle and difficult balance during everyday encounters, from the very top leadership to young employees. Chiang Kai-shek had been promoting a superior Chinese culture and morality for decades and was critical of Western individualism and materialism. Even in a propagandist pamphlet to educate the Chinese about how to properly interact with American soldiers, the Generalissimo reminded them that American officers and soldiers “mostly do not give up their individual material comfort.”71 During the war, Nationalist propaganda celebrated China’s heroic “Big Sword Unit,” who won a major battle against the Japanese in defending the Great Wall, and the superior Chinese troops who supposedly walked in straw sandals and only had two frozen buns to eat compared to America’s “dandy troops” who always had their mouths filled with candies, toffee, gum, or cigarettes. However, Chinese soldiers’ belief in the superiority of the big sword over tanks and porridge over coffee was said to be shaken after witnessing their American allies in action at the front line.72 In reality, Chinese troops, like the majority of the local population during the war, suffered from severe malnutrition, though some benefited from American military rations as a nutritional supplement.73 Even worse, those who had grown accustomed to American coffee while working in India now began to request the “common drink” in Chinese teahouses after the war.74

As previously discussed, the two sides clashed over the appropriate allocation and payment for feeding and accommodating US troops in China. Nationalist officials voiced concerns about the huge costs incurred in supporting GIs’ excessive lifestyle, which strained their finances and exhausted local resources. They also expressed frustration over the apparent lack of respect and appreciation from the American side for the sacrifices made by the Chinese people. Conversely, many Americans felt that the Chinese were ungrateful for US aid and assistance, especially in light of anti-American protests. The critical question of who provided for whom, and under what terms, became a testament to the power relations between the two nations, whether paternal, brotherly, or humanitarian. The mutual feeling of ingratitude was a persistent theme and an underlying source of tension in a relationship of uneven reciprocity.

More broadly, Chinese critics saw food as a bridge to discuss the larger issues of cultural, social, and racial differences and hierarchies. One author explained that American cuisine was very different from the more elaborate Western dishes that had been served in Shanghai restaurants. Typically, breakfast in America consisted of only bread with butter and cereals, occasionally with two eggs in more generous servings. Lunch was simple and dinner was more elaborate, featuring a combination of meat and vegetables. He further commented that, in America, no one enjoyed rare delicacies, nor did anyone eat tree bark, and ordinary people were all healthy. Even the president’s food was not much different from an ordinary worker’s, with the best meals being beef steak, pork steak, chicken legs, and lamb chops.75 Commentaries like this approached food as a representation of American culture, which embodied equality and prioritized nutrition over taste, looks, and quantity. Those who held more critical views, however, questioned whether American food was indeed better or actually suited for Chinese bodies. A Shen bao article refuted the charge that Chinese physiques were not as strong as Westerners’ due to the rice diet, citing a recent American study that linked milk and red meat consumption to higher blood pressure. The author then argued that every nation had its own habits, including dietary practices, and American staple foods were unsuitable for Chinese national habits, as rice had been a staple food for millennia and milk did not fit into most people’s daily habits.76

Such debates continued the earlier controversy over Western and Chinese food, which had been intimately linked to racial strength and national revival since the late nineteenth century. Reformers and revolutionaries had criticized the Chinese character for obsessing over eating and for having unscientific and ancient dietary habits. These customs, such as the preference for vegetables over red meat, supposedly led to differences in Sino-Western bodies and even in national and racial strengths. In the following decades, commentators continued to debate over milk versus soy milk, flour/bread versus rice, and beef over non–red meat diets. In practice, Western cuisines had been localized to adapt to Chinese tastes and ways of eating. For example, restaurants serving Western food added chopsticks instead of knives and forks to allow customers to eat them the Chinese way, and many created a type of “reformed Western food” (gailiang xican) or changed the way certain dishes were typically cooked, such as serving well-done steak and adding soy sauce.77 While some critics linked discussions of food to national differences or racial hierarchies, others focused on Chinese consumption and Westernization instead. One commentator mocked Western-educated students for acting more Western than “real Westerners.” He gave a vivid portrait of such a fictional character, Mary Ma: She eats a sandwich and doesn’t even look at Chinese pancakes and fried dough. To her, although coffee and the famous Dragon Well tea are both bitter, the former has a “tasty bitterness” while the latter is “bitter for no good reasons.” She never watches Chinese movies and only listens to operas, even without understanding much. She chews gum, eats chocolate, and wears clothes emulating American movie stars and models seen in magazines.78 Like in the case of Jeep girls, many of these critiques targeted women, whose consumption of imported nylon stockings, perfumes, cosmetics, clothes, and movies attracted disproportionately large media attention. Their purchases were said not to be a result of increasing gender equality or economic independence, but rather of women selling their bodies for the sake of vanity.

Food was the most common, vibrant, and revealing topic in public discussions on American everyday goods. It occupied the forefront of the debate not only because of its physiological necessity but also because of its unparalleled ability to exert direct and intimate influence. By entering one’s body and altering the inside and outside through nourishment, contamination, or toxicity, food could pose an immediate, visible, and ultimate threat to Chinese individuals and to the national body. As American food and commodities increasingly dominated the Chinese market, critiques shifted focus from national strength and modernization to political discussions centered on socioeconomic impacts. Particularly, attention turned to the devastating impacts of American imports on Chinese industries, including driving national industries into bankruptcy, leading to massive unemployment, and draining precious foreign currency reserves. Critics from different political backgrounds expressed shared concerns regarding the enormous economic pressure local industries faced due to low-cost American surplus and industrial goods (see Figure 5.5). For example, canned food, cigarette, medical, dairy, and textile companies were all crushed by cheaper American manufactured goods that dominated the market.79 Leftist leader Ma Yinchu, a prominent socialist economist educated at Columbia University, emerged as a leading critic, squarely blaming American goods and the global capitalist markets for destroying local workers, businesses, and industries.80 Even pro-government commentators echoed concerns about the perilous nature of “American goods as American disasters,” employing the pun Meihuo to describe these commodities as “sugar-coated poisons.” Many attributed the “invasion of American goods,” together with rampant smuggling and the black market, to the Nationalist Government’s erroneous economic policy that was endangering the entire nation.81

Figure 5.5 “How many coins for a pound of American goods?” Shanghai, 1946. Hai xing.

Figure 5.5Long description

In the background, a pedestrian is seen leaving with goods in hand, while a foreign-looking man walks alongside a woman in Qipao.

Beyond news media, business associations took these debates to official meetings and policymaking sessions, petitioning local and national governments to ban or restrict foreign products to protect national industries. They stressed the distinctions between Chinese and American products and argued that the latter were luxuries and therefore should be prohibited from import during a time of material shortage and foreign currency drain.82 One owner of a canned food business, for example, made three requests: First, the government must limit foreign imports; second, the Chinese must not be infatuated with Western commodities despite their cheaper prices; and third, workers in an industry should cooperate with the owners and endure temporary pain for a better future.83 The Shanghai stocking industry, with the slogan “cherish your country and your skin, please give up nylon stockings,” repeatedly petitioned the government to ban the importation and smuggling of American nylon stockings.84 The results of these petitions varied. Nylon stockings, said to be “luxury goods,” were banned as of August 1948, and even the Shanghai mayor appealed to Chinese women to wear domestic stockings instead.85 Nevertheless, due to pressure from Hollywood, the mayor’s attempt to set up ticket prices for American movies in order to protect the Chinese film industry proved unsuccessful.86 The Shanghai city council discussed a proposal to limit the import of Coke concentrate, but later accepted Watson’s argument that Coke was a regular summer drink, rather than “luxury goods.”87

Business communities in China had been working with Western imported goods for decades and had developed highly adaptive strategies. After the war, some quickly capitalized on American prestige and status, translating this brand power into innovative products. For example, one company advertised a new cigarette brand called “Jeep Car,” while another named a traditional food product “American Guangzhou Mooncake.”88 The “nuclear power” of products “made in the U.S.A.” was transferred to local firecrackers, which were renamed “nuclear crackers,” and to the newly popularized ballpoint pen as the “nuclear pen.”89 However, as competition intensified during an economic crisis, local enterprises began to change gears. Penicillin advertisements now highlighted domestic versions, brands, and even treatments. Soft drink companies added China to their product names, such as “China Prospers” and “Great China,” while others included iconic symbols such as the Great Wall in their trademarks, with slogans like “Chinese people should drink Chinese soft drinks.” Watson’s Coca-Cola commercials, which in the earlier period emphasized Coca-Cola’s “authentic American” identity, now featured “Chinese company” (Hua shang) in big characters to highlight the product’s Chineseness. Ironically, even though it was a company fully owned by the Chinese and had always been seen as a Chinese entity, Watson’s was now attacked by local competitors as being American.90

In a global capitalist system, the divisions between Chinese and American companies and between national and American goods, like these companies’ business interests, remained ambiguous and shifting. The so-called national goods were in fact the result of an “active process of indigenization” pursued by modern Chinese entrepreneurs who mixed the foreign and modern with the Chinese and domestic.91 Even avid promoters of these national goods relied on American raw materials, out of either necessity or choice. For instance, Chinese canned food companies, facing domestic material shortages, used American iron cans and emulated Spam from the surplus supplies to create new “Chinese” products. All local beverage manufacturers used imported concentrated flavor essences for their bottled drinks. These ambiguities reflect Chinese businessmen’s multifaceted relationships with American goods, characterized by both dependency on their sales and challenges posed by competitive pressures.92 This entangled relationship also sheds light on why the Communist campaign against the sale and purchase of American products achieved mixed results.

The national products movement had been a driving force behind the spread of nationalist sentiment since the late nineteenth century. It also provided the foundation for numerous anti-imperialist boycotts against foreign goods, such as the 1905 anti-American boycott that began as a reaction to the Chinese Exclusion Act.93 This time, the campaign served to mobilize urban populations against the Nationalist regime, which was accused of corruption and betrayal. On November 4, 1946, the Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation, known as the Sino-American Commercial Treaty, was signed. The negotiations began almost immediately after the victory over Japan, and the two sides disagreed on many issues, particularly the national treatment and most-favored-nation status for American businesses in China. After its signing, the Chinese press was generally critical of the treaty, chastising it for jeopardizing China’s economic independence and national integrity. The Communists compared the treaty to the notorious “21 Demands” proposed by the Japanese in 1915, calling it a sellout of Chinese interests by the Nationalist regime in exchange for US aid. The treaty created an uproar among a wide range of groups, from leftists and intellectuals to industrialists and businessmen, and elicited protests across major cities.94 The friction continued as China’s economic situation worsened, exacerbated by the influx of American commodities. Rallying under the slogan of “Love using national products, boycott American products,” the Communist Party organized a movement targeting the bulk sale of American surplus property. In Shanghai, underground CCP members convened a meeting on February 9, 1947, inviting prominent leftist intellectuals such as Guo Moruo and Deng Chumin to lecture on the devastating impacts of the American dumping of goods in China. The meeting drew workers from major shopping malls across four districts before being violently broken up by Nationalist-backed worker groups and plainclothes police, resulting in one death and thirteen injuries. Although invitations were widely distributed, owners of national industries who had similar but less radical slogans did not participate in the protest or boycott, nor did many unemployed workers. Overall, the economic stakes were high for many business owners, who were “fed by the American military,” and for the more than ten thousand urban poor who earned their livings as street vendors of American goods.95 Their participation in the cause would have jeopardized their livelihoods. As one scholar has pointed out, local Communist organizers overestimated the workers’ “political consciousness” and the power of patriotism. The event, remembered today as the February Ninth incident in CCP history, failed to attract a substantial number of national capitalists and middle-roaders.96

Despite such setbacks, the American military’s mishandling of issues concerning US goods, which often resulted in excessive violence toward Chinese civilians, raised tensions to another level. This in turn gave the Communists a more compelling cause and a more unifying agenda in their fight against American imperialism as well as the Chiang regime as its running dog.

Halt or Shoot: Guarding US Property

When Brigadier General Omar T. Pfeiffer took command of the marine forces in Qingdao in May 1947, their primary objective was to ensure the security of United States naval training activities. However, the mission was immediately overshadowed by a pressing issue – the “continuing, almost nightly theft of supplies and material from storage areas” (see Figure 5.6).97 By then, marine activities had been terminated in Beijing, Tanggu, and Qinhuangdao, leaving the 1st Marine Division a mere skeleton force. As of September 1, 1947, Qingdao stood as the sole marine duty station in China, with several thousand troops housed in Shandong University buildings and grounds. The small but balanced force, including infantry, artillery, communications, and supporting and service troops, was ready for both offensive and defensive actions. In a revealing account from Pfeiffer’s Marine Corps oral history interview, he recounted an incident he witnessed one night.

Figure 5.6 United States soldiers guarding supplies on deck in Qingdao, December 1949.

Upon hearing a commotion, the general stepped outside the French doors of the second floor sitting room. From the balcony he saw a Chinese man attempting to steal his personal automobile from the garage below, only to be chased and pistol-whipped by his driver, eventually collapsing in a bloody heap. The thief disappeared from the hospital at three the next morning and was never seen again. “My opinion,” General Pfeiffer expressed, “[is that] this man was a Communist thief.” He concluded that these Communist thieves drove American vehicles from the Nationalist areas into Communist-occupied areas, and “that’s why none of these stolen vehicles were ever seen again.” Consequently, Pfeiffer, as the new commanding general, Fleet Marine Force, Western Pacific, gave the following orders to sentries: “When they saw a theft of U.S. Government property taking place [they] were to shout, ‘Halt,’ once in English and once in Chinese and if there was no halt, to let them have it, meaning to fire, and to fire to maim, that is, not to kill but to hit.” As a result, he continued, “in addition to the almost nightly thefts, we had almost nightly killings because of our high velocity and power weapons.”98

Archival records and news reports offer ample information on shooting incidents across various locales before and after Pfeiffer’s orders. The Tianjin municipal archive reveals a sequence of serious events involving locals suspected of theft, which unfolded within days and months of each other.99 On August 26, 1946, a laborer named Wu Liusuo (Wu Liu-so), employed by the 7th Service Regiment in Tianjin to load goods with six other workers, was shot dead by American guards. The GI sentries reported that some stationery supplies had been thrown out of the window of the warehouse to other Chinese on the street. A private first class on duty attempted to stop the workmen at the gate and ordered them to halt but was unsuccessful. He then fired one shot over their heads. Since none stopped, he fired another shot, which instantly killed Wu. “Eleven cartons of pencils were recovered” from the street. About two months later, on the morning of October 24, 1946, seventeen-year-old Hao Wenqing (Ho Wen-ching) was shot in the Tianjin Rifle Range area. While the Chinese police report included testimonies that Hao and another seventeen-year-old were picking up firewood near the compound, the American military authorities claimed that Hao was part of a band of more than twenty armed Chinese who left the camp with US government property, and some appeared to be carrying rifles. The following justification was given: “They were ordered to halt, both in English and in Chinese, but failed to comply with the order, so fire was opened on them.” On the night of November 2, 1946, twenty-year-old Sun Yugui (Sun Yu-kuei) was fatally shot by two marine sentries for attempting to steal an overcoat from a garage. The garage had lost six pieces of clothing in the past and therefore had added sentries on the roof. Earlier in the evening, Sun had been scared off by passersby during his initial attempts. He returned later, managed to pull an overcoat through the garage window, and was shot. Six bullet wounds were found, all in Sun’s upper body. According to the American military investigation report: “The sentries then shouted for SUN to halt,” but he “did not take any heed. The sentries then fired three (3) rounds into the deck, but SUN did not stop. The sentries then fired six (6) rounds into SUN’s body, thus, killing him instantly.” The halt-or-shoot policy continued after these repeated fatal incidents, and in such a rigid environment, even the innocent became casualties. In the early evening of November 13, a Chinese patrolling policeman named Yang was on guard duty in the Chinese Customs Compound where ten American freight cars were parked. Mistaking Yang for a thief in the dark, an American sentry fired a first shot, after which Yang ran away out of fear, and a second .30-caliber bullet was fired, hitting him in the shoulder. The American report explained that the shooting of Yang by Private Boudreau was the result of Boudreau being “unable to identify Yang as a Chinese policeman, in the dark,” as well as Yang’s “failure to understand or to obey Private Boudreau’s command to halt.”

Due to the high demand for American goods, rampant stealing and looting became a major headache for the US military in China. Brigadier General Thomas Gerald noted that the refugees in Qingdao were destitute, “living on what they could scrape together including the bark of trees,” and that “guarding our vast amount of supplies and equipment from a group of hungry refugees presented many problems.”100 Simms, once in charge of billeting and materiel in Tianjin, remembered “the eyes of beggar children and the street thieves” and “the homeless, ragged urchins who had to rely on their sharpness, fleetness of foot and ability to disappear into the crush of the crowd after nipping off with some item of salable nature … there wasn’t much that we Americans had that wasn’t of value to someone.”101 Even though General Pfeiffer was convinced that the nightly thieves were Communists, and the Nationalist media tended to blame them as well, the reality was that there was a mixture of pickpocketing by destitute refugees, impromptu theft by opportunistic coolies and employees, and organized looting by gangsters with sophisticated networks of transportation, money laundering, and sales. But the vast majority remained small-scale civilian thefts and the loot was quickly sold on the black market.

Inside and outside the military compounds, stealing seemed to go on everywhere and could occur at any time. American GIs on the street lost watches, telescopes, gasoline, food, American dollars, guns, and munitions to pickpockets. Packages mailed home were stolen from post offices. Stolen parked vehicles ranged from staff cars, Plymouths, and Willys Jeeps to ambulances.102 To make things worse, in an instant, “obedient servants” transfigured into thieves and were gone in the blink of an eye.103 A laundry boy absconded with the uniforms he had been washing diligently for months. Another cleaning boy stole lightbulbs, torches, a typewriter, a bicycle, and a speaker. A prostitute left the inn with her GI customer’s personal belongings. A typist employed by the American military brought a bag of medicine home “by accident.” After a hard day of work, Chinese laborers threw a few bags over the compound wall. Other contracted coolies who helped the US soldiers clean, sweep, and collect garbage hid a few items in their dump trucks. More organized thieves dug holes in walls or made tunnels leading into warehouses. Even large items, such as 542-pound bombs or 55-gallon drums of aviation fuel, would mysteriously disappear.104 At times, Chinese guards also acted as culprits or coconspirators. A port policeman in Qingdao, in collaboration with workers at the storage house, stole large quantities of American goods during his night shift.105 In a time of collapsing order and harsh living conditions for most, even Nationalist soldiers occasionally stole and robbed, as shown in long lists in the Qingdao municipal archive. As early as January 1946, Chinese sentries challenged marine guards within the same area in the wharf area and “pointed loaded rifles at them whenever they approached,” preventing them from “effectively patrolling their post.”106 Misgivings that these Chinese soldiers could have been involved in suspicious activities were not completely ungrounded. In May 1946, three port policemen who had bought cigarettes, leather shoes, and blankets were shot and wounded by American guards as they were leaving the port.107 Things got even worse on the eve of the American military’s complete withdrawal. In March 1948, more than ten armed Nationalist soldiers attempted to steal from a warehouse while cursing the local police on site: “Why do you intervene in our stealing of American goods?” One of them held a grenade, threatening aggressively.108 A month later, unidentified units of Nationalist troops threatened American guards with guns, broke the locks, and looted the warehouse. They fired toward Chinese guards at the port and escaped in a truck.109

There was no uniform command to fire at Chinese thieves. The army theater’s judge advocate in China during the war had ruled that, in certain cases, GIs could shoot unarmed Chinese individuals suspected of theft, as any theft of American military goods was considered a felony. In response, the Nationalist Government objected to the ruling, questioning whether Chinese sentries could use the same method against US soldiers suspected of burglarizing military warehouses.110 In practice, some US commanders were more cautious about the consequences of such a policy, while others saw it as the sole means to stop or discourage rampant thefts. For example, Pfeiffer’s superior, Admiral Cooke, instructed that the use of firearms against local civilians was intended only as a last resort. He reminded Pfeiffer of the deadly consequences of his shooting orders and the Chinese government’s potential reaction. Known for his close relationship with Chiang Kai-shek and strong opposition to reducing American forces in China, the admiral was said to “take the Chinese side of the thing” “whenever Marines clashed with the Chinese”111 In reply, however, Pfeiffer, who was not “perturbed” by the consequent nightly killings, said, “that was the only way that I knew I could possibly cope with the situation,” adding, “my responsibility was still to the United States and the security of its property.”112

Commander Pfeiffer was not alone in thinking this way. His successor, General Thomas, shared the stance that “a Marine on post with a rifle is told to protect his post, and when somebody busted in there and started to steal something, they’d shoot ’em.”113 When municipal governments raised concerns about these shooting incidents or requested changes of action, the US military’s response, replete with similar rationales, was typically couched in standardized bureaucratic language. First, they cited “the loss of a vast amount of property and supplies” as justification for why “stringent regulations regarding the safeguarding of United States Government property must be rigidly enforced.” Second, they emphasized that the Chinese continually failed to obey the American order to halt. In April 1947, General Howard, Commander of the 1st Marine Division, defended the existing policy in his reply to the mayor of Tianjin. He noted that American goods worth tens of thousands of dollars had been and continued to be at risk. Therefore, marines must protect American property and, when “all other means failed,” would continue to issue firing orders. He further emphasized that the Chinese must halt when ordered by American guards: “If they had halted, they would not have suffered from injury or death.” The number of casualty cases, he further explained, was a result of the linguistic difficulties of American guards as well as the Chinese not following orders.114

These justifications and official replies from high-level American military leadership in China were telling. To borrow the words of Wilma Fairbank, who served as the cultural attaché of the American embassy in China from 1945 to 1947, for the Chinese population, about 70 percent of which was illiterate, “American practice, developed in a very different society half way around the world, required interpretation.”115 Yet, in such life-and-death scenarios, “all other means” simply meant giving an order to halt once in each language. Interestingly, the marine commander acknowledged the “linguistic difficulties of American guards” but failed to address the linguistic and cultural difficulties Chinese civilians faced in understanding the American order in the American way. Notably, the Chinese word for halt that the American sentry presumably memorized was transliterated and pronounced as “Donge-Donge.”116 However, to Chinese ears, this pronunciation was confusing, if intelligible at all. “Donge-Donge,” which sounds like “Dongzhe” (凍着), was not an accurate transliteration to begin with, not to mention how far its many variations pronounced by American soldiers might depart from the original. It actually sounds closer to the word “Dong” (動), which means “move,” the exact opposite of “freeze.” More importantly, “Dong” (凍) was a literal translation of “freeze,” which the Chinese do not use to mean stop.117 Further, there were no comparable legal and cultural contexts in China for understanding the concept of halt or the consequence of being shot even after warning shots had been fired or the suspect had already been hit. This case again illustrates how deeply ingrained sociocultural prejudice and systemic discrimination affected everyday and sensory interactions between American servicemen and Chinese civilians. In other words, in order for the suspect to comply, this individual had to first actually hear the order, irrespective of their physical surroundings, and then linguistically, culturally, and legally comprehend the meaning of the GI’s order to halt. This was a lot to expect from the local suspects who, at that time, were most likely from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, lacking education or even basic literacy. Despite being deemed unreliable by the US military justice system when providing testimonies against their soldiers, Chinese civilians were still held fully responsible for failing to halt or to follow American orders in American terms.

In reality, not all American-guarded goods were “American,” even if they were conveniently labeled “US government property.” Upon arrival, the marines immediately took over the Japanese supplies in the locations they occupied. As Walter Curley, a Yale graduate and aide to General Worton, noted: The Japanese army “had huge stocks of all military supplies – ammunition, clothing, vehicles, weapons, explosives – and the largest cache of food in North China. It operated mills, engineering projects, plants, [and] distribution centers, and carried enormous inventories of fuel, engines, [and] spare parts, and ‘employed’ thousands of people.” In 1946, Curley took the position of Japanese Equipment and Material Control Officer, a new position created solely for the purpose of dealing with the confiscated assets “worth $400 to $600 million, in 1946 dollars.”118 These honeypots of former Japanese supplies attracted a variety of Chinese characters, from local officials to criminals and scavengers. One Chinese thief in Shanghai was shot dead for digging holes in the wall of a warehouse and stealing three packages of sugar, after failing to halt. The former Japanese warehouse for daily necessities and food used to be guarded by the Nationalists and was now temporarily used by the American aviation regiment.119 Regardless, sites now occupied by the American military, whether borrowed, leased, or simply taken, were seen as American properties. Part of the Shandong University campus in Qingdao was used as a marine barracks, hospital, and drilling ground; therefore, entrance to this area by students and the general population was prohibited. A former German resident’s house in Tianjin was now occupied by the marines, with a wooden sign stating “U.S. Gover’t Property, Unauthorized Persons Keep out.”120 In Shanghai, the army and navy authorities set up “no entry” traffic signs outside a theater, the same location where the Japanese had once posted an identical sign. The exclusion of Chinese individuals from entering the navy and army YMCA in Shanghai, in the eyes of a Chinese Christian critic, bore simply too much of a resemblance to the notorious British signpost that allegedly read: “‘No dogs and Chinese allowed.’”121 This evolving political symbol represented not just a personal insult but also direct evidence of Western imperialism.

Smuggling and theft were not monopolized by the Chinese; American personnel actively participated in the lush black market, along with other foreign nationals including Russians, Koreans, Jews, Czechs, and the British. Well known by both sides at the time, GIs routinely traded their supplies while officers also smuggled goods for personal profit. As described by one Chinese interpreter, the “Service of Supplies” was nicknamed “Service of Squeeze” due to its known corruption.122 Many sold “moonlight requisitions,” ranging from basic necessities like food, socks, and uniforms, to even Thompson submachine guns.123 An American officer concluded that the black market for US Army supplies in Kunming “could not have flourished without American help,” a realization that “did not fit well with U.S. criticism of Chinese corruption” or with their own self-portrait.124 In reality, some soldiers sold their own supplies or stolen ones to make extra spending money, while the more resourceful ones worked with Chinese laborers, merchants, and officials to carry out larger operations.125 In November 1945, Major General Shepherd signed an order for “military police to seize and confiscate” all the “non-taxed American cigarettes, liquors, articles of clothing, and food stuffs” sold by local merchants and street venders because they were “identified as United States Government property and are intended for the use of the United States personnel.”126 While the American military pointed fingers at Chinese criminals, rarely were their own personnel court-martialed, nor did these black market dealings draw high-level attention.127 One exception was the case of Marine Colonel Leslie F. Narum and Warrant Officer Burton E. Graham, who smuggled significant quantities of American medicines and pharmaceutical supplies, Chinese furs, and foreign exchange currencies. The case drew American attention not only due to the large scale of the smuggling operation and the involvement of a high-ranking officer, but also because the perpetrators managed to evade customs on both sides, thereby harming American interests as well. Despite these implications, the American military initially tried to keep the case under wraps and requested that Chinese officials handle it as a confidential matter.128

The American policy of taking “stringent actions” to protect its properties had real consequences. It enabled excessive use of force, resulting in deadly shooting incidents across the board, ranging from thieves and suspects to the innocent. Because this policy gave soldiers orders to fire at Chinese civilians, excessive violence also went beyond the sentry-guarded military compounds to other sites where American government properties were supposedly identified: from Chinese streets, stores, and stalls to individual households and bodies. As a result, even consumers of American goods were sometimes put in danger. On September 5, 1946, a marine MP fired two shots while apprehending Cao Guiming (Ts’ao Hui-ming), a student from the Catholic University in Beijing, for wearing American uniform pants. One bullet struck his left leg.129 About three months later in Shanghai, another college student, Gao Ruofan, was forced off his bicycle by American MPs, who then attempted to strip off his American parka. As local crowds gathered, Gao was taken to the American barracks in a Jeep where his coat was removed.130 In reality, used American clothes, including military uniforms, suits, and coats made from military blankets, were highly prized. Known as a “gospel for the literati,” these garments were especially popular among students and teachers who often received them as relief goods or purchased them from stores and vendors.131 American authorities regarded these “U.S. properties,” whether contraband or not, as items to be confiscated on sight. As Provost Marshal Frank R. Harding explained in a letter to the Shanghai Municipal Police Bureau: “I had instructed the military police to check all Parkas worn by civilians as none had been sold by the U.S. Army in the Shanghai area and it would be reasonable to assume that possession would be illegal.”132 As such, any Chinese individual found in possession of American military goods was by default an offender. American soldiers could enforce the order of halt or shoot, and many took the liberty of doing so.