On October 25, 2023, Mike Johnson assumed office as the 56th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, following the historical ousting of Kevin McCarthy by a group of hard-right Conservatives led by Matt Gaetz (R-FL). In his inaugural speech, Johnson addressed the providence of his new role: “I believe that scripture, the Bible, is very clear that God is the one that raises up those in authority, he raised up each of you, all of us. And I believe that God has ordained and allowed us to be brought here to this specific moment and time” (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2023). This was not the first time that Mike Johnson had been vocal about his faith. During Faith Month in 2023, Johnson spoke against the separation of church and state, stating that “the key and essential foundation of a system of government like ours must be a common commitment among the citizenry to the principles of religion and morality” (169 Cong. Rec H1799, 2023). Like Johnson, other members of Congress have not shied away from sharing their religious beliefs. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) has labeled herself a “Christian Nationalist” (Tyler Reference Tyler2022), while Hillary Scholten (D-MI) noted that she is a “pro-choice Christian … guided by passages like Jeremiah 1:5” (169 Cong. Rec H64, 2023). The presence of religion in Congress has been seemingly unaffected by the trends of secularization among the American public (Public Religion Research Institute 2024), with nearly 88 percent of the 118th Congress identifying as Christian (Pew Research Center 2023).

The prominence of religious rhetoric in the House of Representatives, exemplified by the inauguration of Mike Johnson, an outspoken Evangelical, as Speaker of the House underscores the need for a thorough analysis of how such language is used by legislators. Religious rhetoric in political discourse has long been a subject of interest, reflecting not only personal convictions but also strategic political maneuvers (Coe and Chapp Reference Coe and Chapp2017; Domke and Coe Reference Domke and Coe2010). The influence of such rhetoric, particularly when used by influential figures, may shape legislative dialogue and public perception. However, little research has analyzed how Congressional leadership might impact the rhetoric legislators use, let alone their use of religious language. Does Johnson’s inauguration as Speaker of the House influence the use of religious rhetoric by other members of Congress, especially considering his backing by Trump-led Republicans? Furthermore, does this rhetoric differ between legislators from different political parties and in their communications with their fellow representatives compared to how they address their constituents?

Previous scholarship has explored the use of religious language by political elites, shedding light on its prevalence and strategic deployment across partisan lines (Campbell, Green, and Layman Reference Campbell, Green and Layman2011; Castle et al. Reference Castle, Layman, Campbell and Green2017; Chapp and Coe Reference Chapp and Coe2019; Knoll and Bolin Reference Knoll, Jo Bolin, Paul, Mark and Ted2020). While much scholarship has been devoted to the executive branch, with analyses of presidential speeches revealing nuanced shifts in religious references over time (e.g., see Coe and Chenoweth Reference Coe and Chenoweth2015; Domke and Coe Reference Domke and Coe2010; Hughes Reference Hughes2019), less attention has been paid to the impact of such rhetoric within the legislative arena. Studies examining religious language used by members of Congress hint at its significance, suggesting correlations between religiosity, legislative behavior, and constituents’ preferences, for example, see Bramlett and Burge Reference Bramlett and Burge2021; Dreier et al. Reference Dreier, Gade, Wilkerson and Schaeffer2021; McGuffee Reference McGuffee2012). Further, scholarship points to the impactful role that the leadership of the Speaker of the House can have on the behavior of congresspeople (Green Reference Green2010). Notably absent in research, however, is the specific role played by leadership positions within Congress, such as the Speaker of the House, in shaping the religious discourse used by members of Congress.

In this paper, we seek to address this gap by analyzing the change in representatives’ use of religious rhetoric in their floor speeches and e-newsletters after Mike Johnson became Speaker of the House on October 25, 2023. Johnson has often been described as a Christian nationalist, reflecting his strong alignment with conservative Christian values (Whitehead and Perry Reference Whitehead and Perry2023). His rise to the position marks the first Protestant Speaker in 16 years (Scanlon Reference Scanlon2023), a distinction that could potentially influence a largely Protestant-affiliated Congress (Pew Research Center 2023). We begin by evaluating the literature on religious rhetoric, political communication, and the role of leadership in Congress. We then turn to our analysis of the text of House speeches and e-newsletters, which are readily available via the Congressional Record and DC Inbox. We measure change in religious rhetoric by counting both the number of religious speeches or newsletters a representative gives and the number of religious terms within speeches and newsletters. We employ difference-in-differences (DiD) regressions and difference-in-difference-in-differences (DiDiD) regressions to examine changes in the frequency of religious rhetoric in speeches and newsletters after Johnson assumed office as Speaker, as well as the impact of partisanship. Our findings show that while the frequency of religious language in House speeches actually decreased after Johnson became Speaker, the use of religious rhetoric in newsletters sent by Republican representatives increased. We conclude with a discussion of the limitations of this study and avenues for future research.

Our findings contribute substantially, theoretically, and methodologically. First, we contribute to the theory that leadership in Congress can influence the behavior of legislators (Green Reference Green2010) and that legislators craft a specific “home style” (Fenno Reference Fenno1978) when interacting with their constituents. Secondly, our findings substantively contribute to the intersection of partisanship and religion in the American legislature. We show that the influence of partisanship becomes more pronounced in shaping religious language when communicating with audiences outside of Congress, such as constituents. The divergent patterns between Republican and Democratic use of religious rhetoric in newsletters illustrate how the perceived audience can influence the language members of Congress use and the impact of increased polarization on legislators. Finally, our methodology utilizes DiDiD regression analysis—a tool that is underutilized in the field of religion and politics. Ultimately, our analysis offers valuable insights into the evolving landscape of legislative discourse within the United States Congress.

Religious rhetoric and political communication

Existing literature in the field focuses on the use of the “God talk” and “God strategy” by political elites (Knoll and Bolin Reference Knoll, Jo Bolin, Paul, Mark and Ted2020). “God talk”—that is, the use of religious rhetoric (Calfano and Djupe Reference Calfano and Djupe2009; Coe and Domke Reference Coe and Domke2006; Djupe and Calfano Reference Djupe and Calfano2013)—is used by both Republicans and Democrats alike (Balmer Reference Balmer2008; Chapp and Coe Reference Chapp and Coe2019). More specifically, “God strategy” refers to the use of religious rhetoric motivated by both sincere religious beliefs and strategic political goals (Coe and Chapp Reference Coe and Chapp2017; Domke and Coe Reference Domke and Coe2010). Most research on the use of “God talk” and “God strategy” by political elites focuses on the executive branch and the use of religious rhetoric by the president, as religious language is a consistent aspect of presidential speeches, used to signal to certain societal factions (Coe and Domke Reference Coe and Domke2006). In a content analysis of hundreds of presidential addresses, Hughes (Reference Hughes2019) found that presidents from Roosevelt to Trump often used religious language strategically, with its use increasing over time, culminating in Trump’s presidency, which featured the highest frequency of religious references. Similarly, Domke and Coe (Reference Domke and Coe2010) found that since Reagan, presidents have increasingly invoked God and faith, making direct references to God a more consistent and prominent part of their speeches. Audience played an important role in this rhetoric: presidents who had a higher proportion of mainline and evangelical Protestants in their electoral coalition were more likely to employ religious rhetoric in their major addresses (Kradel Reference Kradel2008).

A growing body of literature has also studied how members of Congress use religious language. In their analysis of 1.5 million tweets from members of Congress, Bramlett and Burge (Reference Bramlett and Burge2021) found that both Republican and Democratic members used a “religious code” on Twitter to indicate their own identity and activate their constituents’ religious identities, with Republicans using the code more extensively and with Judeo-Christian specific terms. Analyses of congressional websites and online biographies found that Republicans, ideological conservatives, Southerners, and legislators with more religious constituents were more likely to include religious references (Gade et al. Reference Gade, Dreier, Wilkerson and Washington2021). Legislators also used such language strategically, using religious rhetoric to co-opt issues that belong to the other party, such as Republicans discussing healthcare or Democrats addressing the economy and defense (Hughes Reference Hughes2019, Sides Reference Sides2006). Legislators’ religiosity may also impact their actions beyond just their rhetoric, influencing their voting behavior (Fastnow, Grant, and Rudolph Reference Fastnow, Grant and Rudolph1999; Guth 2014; Richardson and Fox Reference Richardson and Wightman Fox1972; Schecter Reference Schecter2001; Yamane and Oldmixon Reference Yamane and Oldmixon2011; McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013).

Political elites’ decision to use religious language has two main impacts. First, religious rhetoric may affect how voters view legislators. As electoral incentives heavily shape legislators’ priorities (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974), legislators are motivated to craft a compelling “home style” that resonates with their constituents (Fenno Reference Fenno1978). This dynamic underscores the relationship between electoral imperatives and legislative behavior, helping to explain how legislators’ view of the partisan or religious makeup and preferences of their constituency could influence and alter their own actions. Because “members of the House of Representatives represent distinct and often religiously homogeneous districts” (Knoll and Bolin Reference Knoll, Jo Bolin, Paul, Mark and Ted2020 1126), candidates can use this language as a signal to certain voters. Such language may draw on religious stereotypes: Evangelicals are seen as conservative, competent, and trustworthy (McDermott Reference McDermott2009), attracting more Republican votes (Campbell, Green, and Layman Reference Campbell, Green and Layman2011). Religious language can enhance perceptions of trustworthiness and morality, as religious candidates, regardless of partisanship, are perceived as more trustworthy (Clifford and Gaskins Reference Clifford and Gaskins2016). However, overtly religious messages can alienate outside groups and can be more polarizing than subtle cues (Albertson Reference Albertson2015; McLaughlin and Wise Reference McLaughlin and Wise2014). For this reason, candidates may choose to utilize “multi-vocal appeals” that only in-group religious members can pick up on, also called “Dogwhistles” (Albertson Reference Albertson2015). Still, other studies note that religious cues may matter less to voters than secular information, such as ideology and race (Weber and Thornton Reference Weber and Thornton2012, Simas and Ozer Reference Simas and Ozer2017, McLaughlin and Thompson Reference McLaughlin and Thompson2016). Ultimately, legislators may strategically use religious rhetoric, adopting their presentational style to emphasize values their constituents support to influence their constituents’ view of them and the work they do (Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013).

Second, the use of religious rhetoric may have societal consequences. When legislators or candidates use religious language, they can inadvertently influence the religious socialization of the public and embed norms that political leaders are Christian (Coe and Domke Reference Coe and Domke2006). This can strengthen the civic religion seen in America today, further tying patriotism to religious faith. For example, the addition of “Under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance during the Cold War highlights America’s unique culture with shared values and customs based on the relationship between civic and religious life.

This civic religion in America can impact who is seen as a viable candidate for public office. In 2016, 62% of respondents to a Pew poll agreed that it was important that a president have strong religious beliefs (Smith Reference Smith2017), a sentiment that was still held by nearly half of Americans four years later (Bruce Reference Bruce2020). Voters are also much less likely to vote for a secular candidate (Castle et al. Reference Castle, Layman, Campbell and Green2017). The more candidates and legislators use religious language, the deeper entrenched civic religion becomes in America, and the more difficult it becomes for non-religious candidates to be elected into office. This dynamic can be further exacerbated by polarization when one party becomes closely entwined with religion. Since the election of Trump in 2016, more conservative Americans are identified as evangelical, even though many rarely, if ever, attend church and have no attachment to Protestant Christianity (Burge Reference Burge2021). This disparity suggests that for many, evangelical identity is now more of a political marker than a religious one, further entrenching the association between Republicanism and Christianity. As a result, religious rhetoric not only influences American elections but also shapes broader political culture and representative dynamics (Chapp Reference Chapp2012).

Leadership in congress

The role of the Speaker of the House is established in Article I, Section II of the United States Constitution. Since its inception, the position has come to perform both partisan and nonpartisan responsibilities, particularly in guiding the House to pass legislation (Green Reference Green2010). Today, the Speaker of the House is also responsible for “establishing rule-making precedents, evaluating points of order related to floor procedures, referring legislation to committees, and influencing legislators’ committee assignments” (Green Reference Green2010, 4). Like other members of Congress, the Speaker of the House is motivated by (re)election, in addition to ensuring their desired policy is passed and maintaining internal influence (Fenno Reference Fenno1973). However, while seeking re-election to the legislature, the Speaker of the House also seeks re-election to their position—“an office of great honor and influence” (Galloway Reference Galloway1955, 346).

The Speaker wields significant power over the legislative process by manipulating the legislative agenda, crafting bills, and strategically referring legislation to committees (Green Reference Green2010). One of the Speaker’s most potent tools is floor advocacy, where they speak on the House floor to advocate for specific legislative outcomes. This method, combined with other leadership tactics, leverages the Speaker’s authority and credibility to sway votes and influence legislative results (Green Reference Green2010). Additionally, the Speaker can affect outcomes by influencing committee assignments, which can alter the trajectory of legislation and the priorities of individual representatives (Green and Harris Reference Green and Harris2019). Scholars often measure the impact of party leadership by analyzing roll-call votes to determine how party alignment and leadership directives shape legislative behavior (Snyder and Groseclose Reference Snyder and Groseclose2000). Through these mechanisms, the Speaker of the House not only directs the flow of legislation but also molds the legislative behavior and decisions of House members, ensuring alignment with broader party goals and strategic objectives (Green Reference Green2010).

In addition to formal powers, the Speaker’s role as a symbolic leader is significant. Like other party leaders, the Speaker has the potential to influence the rhetoric of their followers. Party leaders, including presidents, often frame issues in ways beneficial to their party, influencing how rank-and-file members communicate with their constituents (Lee Reference Lee2016, Cavari Reference Cavari2017). Parties or political elites can have “brands,” which can set them apart as trustworthy, reputable, or holding a certain identity (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2020, Lees-Marshment Reference Lees-Marshment2014). Party members may adopt a political leader’s brand if they believe it will be electorally beneficial. For example, during the 2020 election many Republican candidates were more likely to embody the “Trump Political Brand” on Twitter, mimicking Trump’s communication style by things such as tweeting aggressively or tweeting in all-caps (Horan et al. Reference Horan, Brubaker, King and Meinhold2024). In the case of religious rhetoric, the Speaker’s personal religiosity and use of “God talk” (Coe and Domke Reference Coe and Domke2006) may serve as a signal to members that such language is both permissible and advantageous. This creates a “permission structure”—that is, the implicit and explicit cues that leaders provide, which encourage or dissuade members from adopting particular strategies or behaviors (Holland and Bohan Reference Holland and Bohan2013). For example, a Speaker’s public invocation of religious themes can encourage like-minded legislators to incorporate similar rhetoric, particularly when such language aligns with the Speaker’s ideological commitments and the broader priorities of their party.

Despite these insights, the causal mechanisms through which the Speaker influences rhetorical behavior remain under-explored. Much of the existing literature focuses on the Speaker’s procedural and policy influence, while research on their impact on rhetorical norms is still in its infancy. Green (Reference Green2010) notes that studies on the Speaker’s broader influence are relatively nascent, with significant gaps in understanding how leadership shapes communication styles within Congress. This gap is particularly evident in studies of religious rhetoric, where the relationship between leadership signaling and member behavior has yet to be fully theorized or empirically tested.

Case selection

The election of Mike Johnson as Speaker of the House in October 2023 provides a unique case for studying the intersection of religious rhetoric and political leadership in Congress. Johnson is the first Protestant Speaker in 16 years (Scanlon Reference Scanlon2023; Pinho Reference Pinho2023) and is vocal about how his religious beliefs are central to his political identity. When first running for Congress in 2016, he stated, “I’m a committed Christian and my faith informs everything I do” (Hensley Reference Hensley2023). Whitehead and Perry (Reference Whitehead and Perry2023) note that while Johnson has not explicitly identified himself as a Christian nationalist, his rhetoric and policy positions align with a broader Christian nationalist ethos, a framework advocating for the fusion of a particular Christian worldview with American civic life and governance.

Johnson’s ties to Christian nationalism have drawn scrutiny, particularly from members of the Congressional Freethought Caucus (CFC). In a report titled Speaker Johnson: Christian Nationalism in the Speaker’s Office?, the CFC asserted that “Speaker Johnson is deeply connected in political practice and philosophy to Christian Nationalism, more so than any other Speaker in American history” (Walker Reference Walker2024). The report further argues that Johnson has spent decades working to “deny, reject, and undermine the constitutional separation of church and state, including trafficking in fake histories about our nation’s founding.” This characterization was echoed by Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-MD), who stated on X that Johnson’s leadership “is what theocracy looks like” (2023). Republican legislators have also recognized how religious the speaker is; five months before Johnson assumed his position as Speaker, Rick Allen (R-GA) shared on the floor, “As my friend Mike Johnson explained to me, what our Founders did was simply this: They left God at the top, they got rid of the king, and put the people in charge” (169 Cong. Rec H1799, 2023).

Beyond his religious rhetoric, Johnson also enjoys the full endorsement of Donald Trump, further solidifying his position within the Republican Party’s ideological landscape. Ahead of the House vote to elect a Speaker in December 2024, then-President-elect Trump posted on Truth Social: “Speaker Mike Johnson is a good, hard-working, religious man…Mike has my Complete and Total Endorsement. MAGA!” (Brooks Reference Brooks2024). This endorsement, coupled with Johnson’s longstanding emphasis on religious values in governance, solidifies his distinct position among modern Speakers of the House. Even though past Speakers have been religious, few have utilized religion in a way Johnson has. Of the three past speakers, only two mentioned religion in their inaugural speeches (excluding the expected “God bless America”): Nancy Pelosi mentioned the importance of being “good stewards of God’s creation” (2019), while Paul Ryan asked legislators to pray for each other (2015). Representatives clearly saw this distinction; only two legislators wrote to their constituents about Pelosi or Ryan’s faith after they were elected. By contrast, 31 Republican representatives mentioned the Speaker Johnson’s religiosity in their newsletters to their constituents.Footnote 1

While the influence of party leaders is not unique, Johnson’s ideological positioning, his explicit religious framing of policy—particularly as indicated in his inaugural speech as Speaker—and the discourse surrounding his speakership set him apart. As Speaker, he holds a critical leadership position within his party, and his ascension was rife with controversy and debate (Vazquez et al. Reference Vazquez, Mariana Alfaro, Theodoric Meyer, Goodwin and Wang2023), making him a particularly interesting figure in the eyes of the nation. The extent to which his leadership has shaped religious rhetoric in Congress presents a compelling case for examination, particularly given that party leadership has influenced legislators’ behavior in the past.

Hypotheses

We have demonstrated that congressional leaders can shape legislators’ behavior and that religious language serves various strategic purposes in legislative discourse. Given this, there are three key reasons to expect an openly religious Speaker to influence Republican representatives’ use of religious rhetoric. First, Johnson signals to legislators that religious language is not only acceptable but encouraged. As the U.S. grows increasingly secular, representatives may hesitate to use explicitly religious rhetoric for fear of alienating constituents. However, Johnson’s approach reassures them that such language has a place in legislative discourse. Representative Keith Self (R-TX) echoed this sentiment, writing to his constituents, “It is apparent that Johnson’s faith is a guiding force in his life and it was inspiring to hear him mention this on the house floor.” After quoting Johnson’s opening statement on God and the Bible, Self concludes, “I can’t tell you how encouraging it was to hear these words” (Self Reference Self2023). Still, given the Republican Party’s longstanding ties to religion, this alone may be the weakest of the three explanations.

Second, Johnson’s election as Speaker of the House signaled not only his own views on the role of religion in politics but also the priorities of part of the modern Republican Party. By invoking the relationship between religion and politics in his opening speech, Johnson signals to Republican legislators that religion remains a priority of the Republican Party. Prior research shows that party leaders shape legislative priorities, and members are quick to fall into line (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins1993; Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013). This pattern is evident in how many Republican legislators adopted Trump’s distinctive communication style on Twitter, suggesting that members are highly responsive to leadership cues (Horan et al. Reference Horan, Brubaker, King and Meinhold2024).

Finally, since Johnson’s rise was driven by the MAGA-aligned faction of the Republican Party, Republican representatives may see religious rhetoric not just as a reflection of Johnson’s personal beliefs, but as a necessary signal of allegiance to this emerging power center. According to former Representative Matt Gaetz (R-FL), “The swamp is on the run, MAGA is ascendant, and if you don’t think that moving from Kevin McCarthy to MAGA Mike Johnson shows the ascendance of this movement, and where the power of the Republican party truly lies, then you’re not paying attention” (Gaetz Reference Gaetz2023).

Conversely, as Johnson’s leadership further entwines religion with the Republican Party, Democratic legislators are likely to distance themselves from religious rhetoric. Johnson’s ties to Christian nationalism have been widely criticized by Democratic lawmakers (Walker Reference Walker2024), including Representative Jared Huffman (D-CA), who wrote to his constituents, “Speaker Johnson embodies one of the most serious threats to democracy of our time: an outright rejection of the separation of church and state and documented ties to extreme Christian nationalism… he’s more interested bending public policy to reflect his personal religious views, which is a slippery slope to theocracy and governing under one imposed religion” (Huffman Reference Huffman2023). Given these criticisms, Democratic legislators may be even more inclined to distance themselves from religious rhetoric, reinforcing a partisan divide in religious discourse. Even if some religious Democrats feel compelled to offer an alternative religious perspective, the broader partisan dynamics may lead most Democratic legislators to reduce their religious rhetoric.

We expect that representatives will adapt their rhetoric when talking to their fellow legislators on the House floor and in newsletters to their constituents to reflect these trends. Thus, from these expectations, our first hypothesis with its sub-hypotheses follows:

Hypothesis 1A: Johnson’s assumption of office will positively impact Republican representatives’ usage of religious language in House speeches compared to Democratic representatives’ usage.

Hypothesis 1B: Johnson’s assumption of office will positively impact Republican representatives’ usage of religious language in newsletters compared to Democratic representatives’ usage.

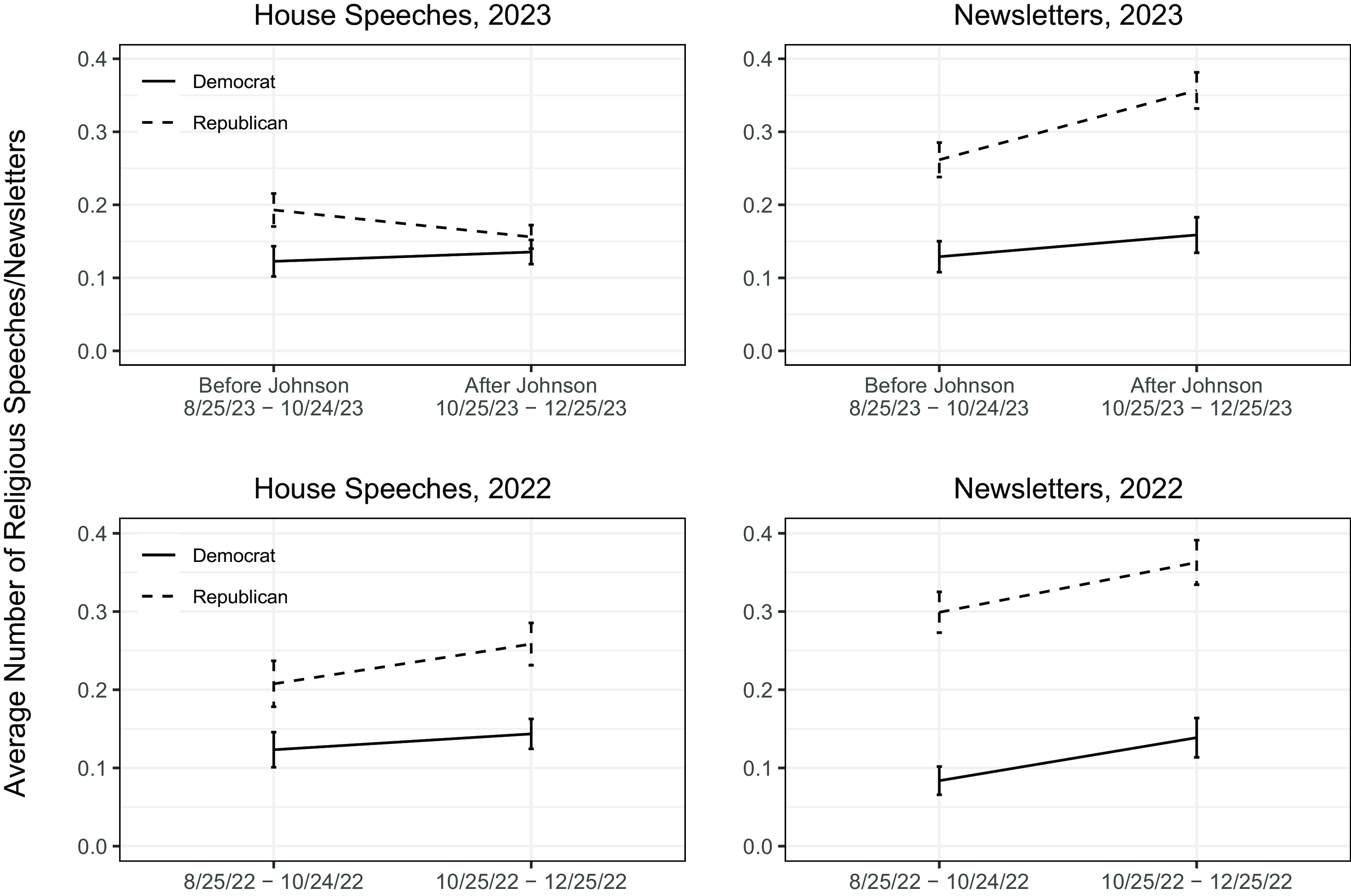

We run two analyses to test this hypothesis. First, we use a DiD model to compare religious rhetoric used by Republican representatives to Democratic representatives from two months before Johnson became Speaker on October 25, 2023 to two months afterward. Democrats act as a control group to account for other nonpartisan factors that may have caused an increase in religious speech among both periods during the period of study. Hypothesis 1A would be correct if there is an increase in the number of religious House speeches or religious terms used in speeches, and Hypothesis 1B would be correct if there is an increase of religious newsletters or religious terms used in newsletters given by Republican representatives compared to Democratic representatives during this period. To ensure that this difference is not due to simply the holiday season, our second test is a DiDiD model. This model uses the same comparisons as our (DiD) model but further compares it to the same groups and time period in 2022. For Hypothesis 1A or 1B to be correct, we would expect to see a positive increase in the number of religious speeches or newsletters, or the number of religious terms used in speeches or newsletters, by Republican representatives in 2023 compared to Democrats and the use of religious rhetoric by both parties in 2022.

Based on the literature, we also note that elected officials use different rhetoric when addressing different audiences (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974; Neumann Reference Neumann2019). Thus, we would expect legislators to use different language when addressing their colleagues on the floor of Congress compared to how they write to their constituents in a newsletter. These newsletters are sent out by nearly every member of Congress, intended to showcase their achievements and policy positions to their constituents. An analysis of legislators’ e-newsletters found that both Republican and Democratic congresspeople were more likely to show a more extreme ideology in their newsletters compared to their behavioral ideology (Cormack Reference Cormack2016). We expect this to apply especially to religious language, as it is found to potentially have a stronger impact on voters than non-religious language, particularly when looking at partisan effects (Castle et al. Reference Castle, Layman, Campbell and Green2017). As religious language is viewed as more partisan, we expect Republican representatives to use it at higher rates when addressing their constituents in newsletters after Johnson assumes office compared to how often they use it on the House floor. As Johnson’s election as Speaker may represent a new direction for the Republican Party, legislators may believe their voters may also value more extreme ideological beliefs and policies, leading legislators to change their language to reflect such. Our second hypothesis follows:

Hypothesis 2: Johnson’s assumption of office will impact Republican legislators’ usage of religious language in their newsletters more than it will impact their usage of religious language in their House speeches.

To test this hypothesis, we specify the distinctions between religious references given in House speeches and newsletters in our two tests for our first hypothesis. If our second hypothesis is correct, we expect to find a different impact of Johnson on speeches and newsletters, and this difference should indicate that representatives use more religious language in their newsletters than in their speeches.

Data

We pull from two data sources: speeches made on the House floor, in which legislators addressed each other; and representatives’ e-newsletters, in which legislators addressed their constituents.

In order to analyze speeches made in the House, we obtained all speeches made in the House between August 25, 2022 and December 31, 2023. Most of these data were provided courtesy of the Polarization Research Lab, and we supplemented any missing dates with our own collection of floor speeches using the Congressional Record (Congressional Record).Footnote 2 These speeches include anything said by representatives included in the Congressional Record. Each speech was counted as a segment in which a congressperson spoke; for instance, if a floor debate occurred and a congressperson was briefly interrupted, that speech is counted as two separate speeches, with the interrupting congressperson’s comments also counting as one speech. We dropped speeches that were less than 350 characters long to exclude short statements, such as legislators asking how much time they had left to speak, and speeches where legislators gave personal explanations as to why they missed a vote.

We used DCinbox (DCinbox), a source which collects congress members’ e-newsletters, to gather representatives’ e-newsletters. These newsletters are sent out by nearly every member of Congress. Lindsey Cormack, who created this resource, found in a 2012 CCES question that 19% of respondents had signed up to receive their representative’s newsletter and 14% had signed up for their Senator’s newsletter (Cormack Reference Cormack2016). These subscribers tended to be older, wealthier, more politically active, and more extreme.

To test our hypotheses, our analysis is limited to two months before and after Johnson became Speaker, August 25th through December 25th. We compare the speeches from this period in 2023 with the speeches from this same period in 2022. This resulted in 5,951 speeches in 2023 and 4,009 speeches in 2022. We used all representatives’ e-newsletters collected by DCInbox sent during the same time frame as our data on congressional speeches. This gave us 4,798 newsletters in 2023 and 4,079 in 2022.

In searching for religious rhetoric, we split chosen religious terms into six separate dictionaries. As we are looking for trends over time, we opted for a broader, limited dictionary as opposed to attempting to find every instance of religious speech. These dictionaries, with their included terms,Footnote 3 are listed below:

-

God: god, jesus, christ, savior, our/the lord, holy spirit

-

Blessings: bless, faith, worship, pray, divine, salvation, sin, heaven, holy, spiritual

-

Scripture: scripture, bible, biblical, psalm, ten commandments

-

Religion: religion, christian, gospel

-

Political: judeo, religious freedom, religious liberty, freedom of religion, christian nation

-

Dogwhistle: pornography, gender ideology, gender agenda, pro-family, traditional family, traditional marriage, unborn, pro-life, protect life, abortion agenda

We analyzed these dictionaries separately and, with the exception of terms in the Dogwhistles dictionary,Footnote 4 added together as a single dictionary, ensuring that each phrase was only counted once, which we labeled “Religious Terms.”Footnote 5

Descriptive analysis

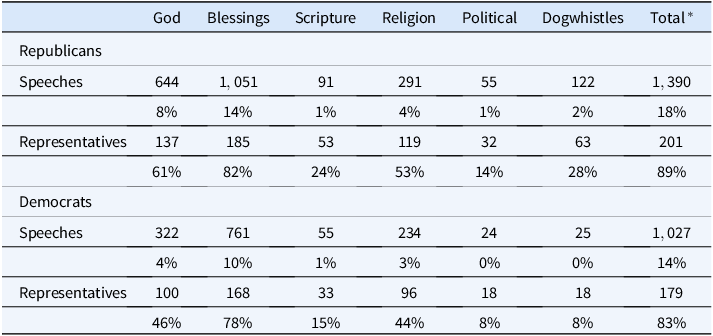

We begin with a descriptive analysis of the use of religious language by representatives on the House floor during 2023. Table 1 reports the total number and percentage of speeches given in the House which included at least one religious word, as well as how many representatives who spoke on the floor at least once during 2023 used these religious terms. These data are further broken up into religious topic and party.

Table 1. Number and percentage of speeches and representatives who used religious terms in House speeches in 2023

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}$

Excluding Dogwhistle terms

${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}$

Excluding Dogwhistle terms

Table 1 shows that Republicans used religious references at a higher rate than Democrats on the House floor: 18% of Republican speeches included at least one religious term, compared with 14% of Democratic speeches. Furthermore, 201 Republican representatives, or 89% of Republican representatives who spoke on the House floor in 2023, gave at least one speech which included a religious term, compared to 179 or 83% of Democratic representatives. Both of these differences are statistically significant (

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

and

$p \lt 0.01$

and

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

, respectively). When it came to specific religious topics, both Republicans and Democrats spoke most often with “Blessings” terms followed by “God” terms, though Republicans had a higher percentage of speeches that used these terms compared to Democrats. A t-test comparing the amount of religious words used by representatives indicates that Republican legislators used more religious words on average (16.8 compared to Democrats’ 11.0), a difference which is statistically significant at the 5% level.

$p \lt 0.1$

, respectively). When it came to specific religious topics, both Republicans and Democrats spoke most often with “Blessings” terms followed by “God” terms, though Republicans had a higher percentage of speeches that used these terms compared to Democrats. A t-test comparing the amount of religious words used by representatives indicates that Republican legislators used more religious words on average (16.8 compared to Democrats’ 11.0), a difference which is statistically significant at the 5% level.

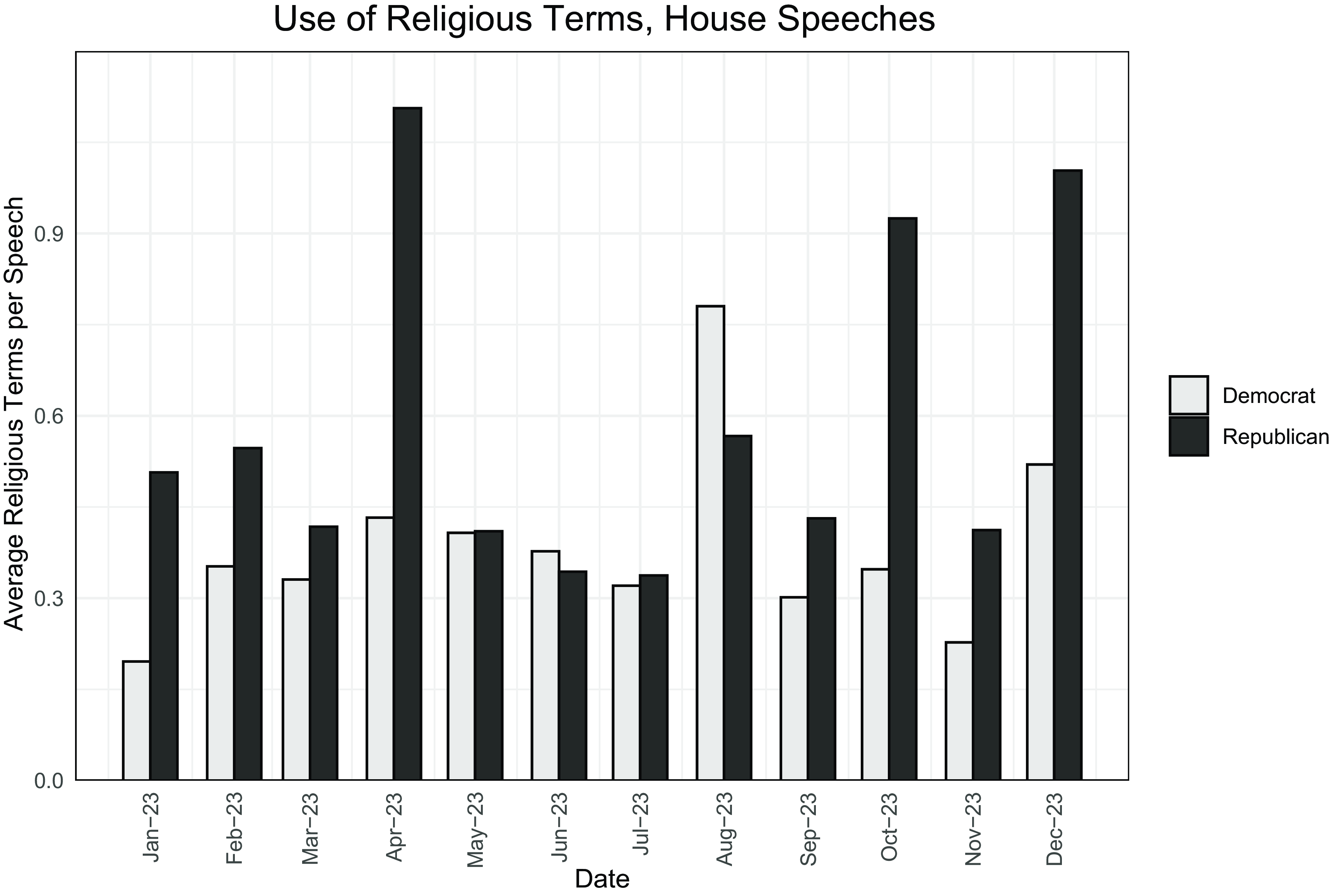

To better showcase the partisan differences in religious usage, Figure 1 shows the average number of religious terms per speech each month by Republicans and Democrats. Figure 1 illustrates that Democrats use religious language rather consistently through 2023, with a rare high in August.Footnote 6 Republicans’ use of religious language is much more variable, primarily due to celebrating religious events and holidays. For example, the date with the most religious rhetoric is December 11, 2023 with 348 religious references due to the House celebrating Bible Week, during which various legislators spoke on the Bible and its influence on America (Flick Reference Flick2023). April had the highest average religious terms per speech due to the celebration of Faith Month, a holiday began in 2022 by Concerned Women for America to celebrate how faith benefits society (McPhee Reference McPhee2023). October also has high average religious terms for Republicans, largely due to Representative Jefferson Van Drew (R-NJ) giving 37 speeches before October 25th, all of which recognized individuals from his district and ended with “God bless [individual], and God bless the United States of America.”

Figure 1. Average number of religious terms in House speeches, by party.

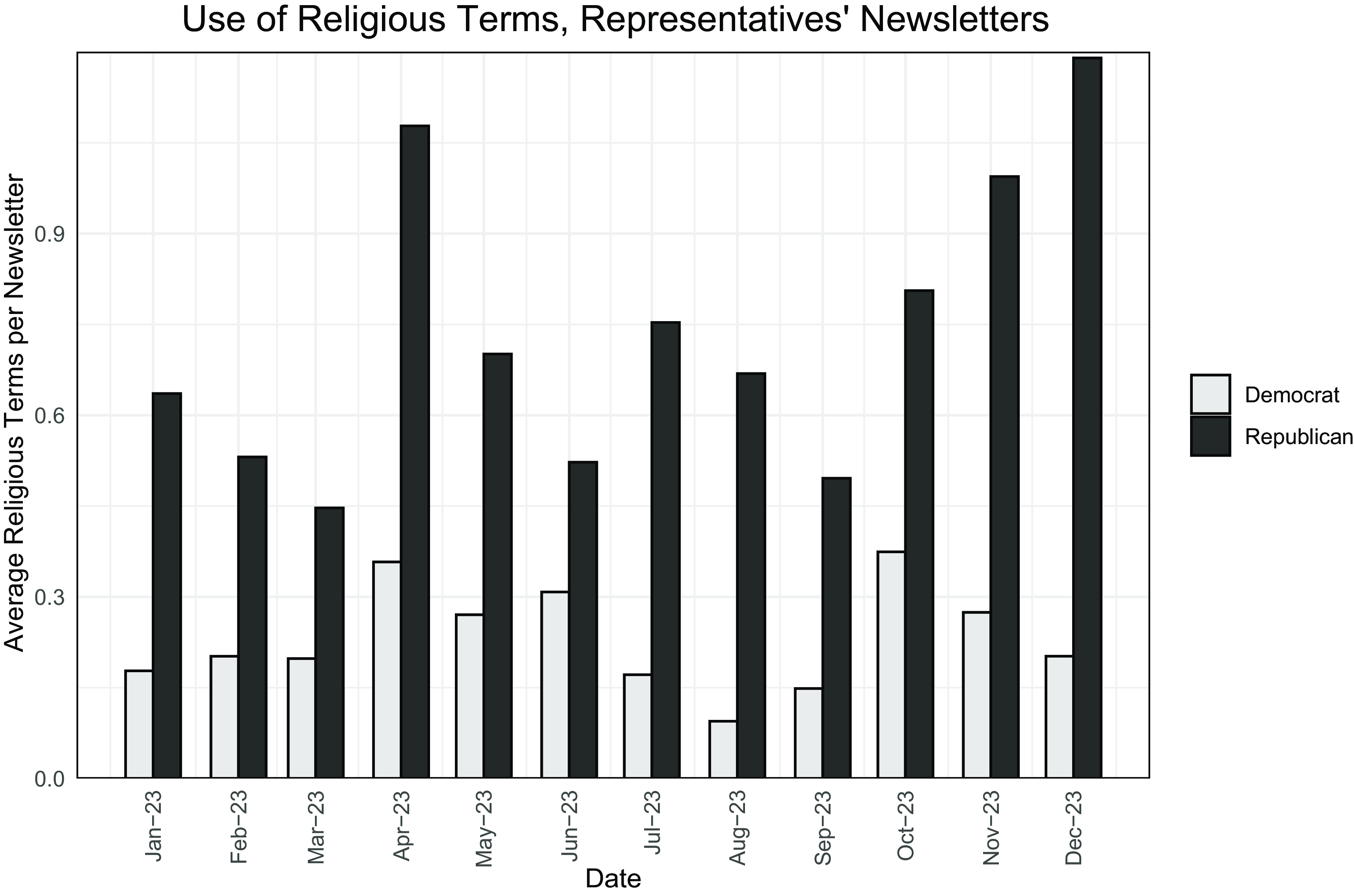

To better understand how representatives may discuss religion with their constituents, we turn our analysis to the use of religious rhetoric in congressional e-newsletters. Figure 2 shows the average religious terms used per newsletter each month in 2023 by party. This figure stands in stark contrast to our earlier findings on House speeches. When it comes to newsletters, Republicans consistently invoke religious speech more than Democrats at a rate of three to one or higher. This indicates that representatives discuss religion in different terms depending on their audience: when addressing their colleagues, Republicans may not be as pressured to use religious terms, while Democrats feel more comfortable using them, and such pressure reverses when addressing their constituents. Further data on the number and percentage of newsletters and representatives who used religious terms in their newsletters in 2023 can be found in Table 1 in the Appendix.

Figure 2. Average number of religious terms in newsletters, by party.

Does Mike Johnson’s assumption of the office of the Speaker of the House influence the use of religious rhetoric in either of these situations? We turn to statistical analyses to answer this question.

Results

Difference-in-Differences (DiD)

To test our first hypothesis to determine whether Johnson positively impacted Republican representatives’ usage of religious language compared to Democratic representatives’ usage, we conduct a DiD regression. This regression analyzes the effect of a treatment on two different groups, one treated and one untreated, by comparing the average change in the treated group to the average change in the untreated group from before and after the treatment occurred. We compare Republicans, our “treated” group, to Democrats, our “untreated” group, using the date Johnson became Speaker as the treatment.Footnote 7 We compare speeches given in the two-month period before Johnson became Speaker (August 25—October 24, 2023), or P1, to speeches given in the two-month period after Johnson became Speaker (October 25—December 25, 2023), or P2. Below is the equation for the estimator for effect of treatment for Republicans:

We run four separate DiD regressions. Each regression interacts with the partisanship of the legislator giving each speech (1 for Republican, 0 for Democrat) with a binary variable indicating if the speech was given before (0) or on the day of or after (1) Johnson became the Speaker on October 25, 2023. Each regression had a different dependent variable, all of which are listed below:

-

The number of religious terms in each House speechFootnote 8 ;

-

The number of House speeches which included at least one religious term (binary variable);

-

The number of religious terms in each representative’s newsletter;

-

The number of newsletters which included at least one religious term (binary variable).

We include fixed effects and clustered standard errors for legislators in all regressions. This allows us to control for the difference in religion, race, region, and other demographics between legislators. We also exclude Johnson’s inaugural speech as Speaker given on October 25, 2023. The results for these regressions can be found in Table 2 in the Appendix.

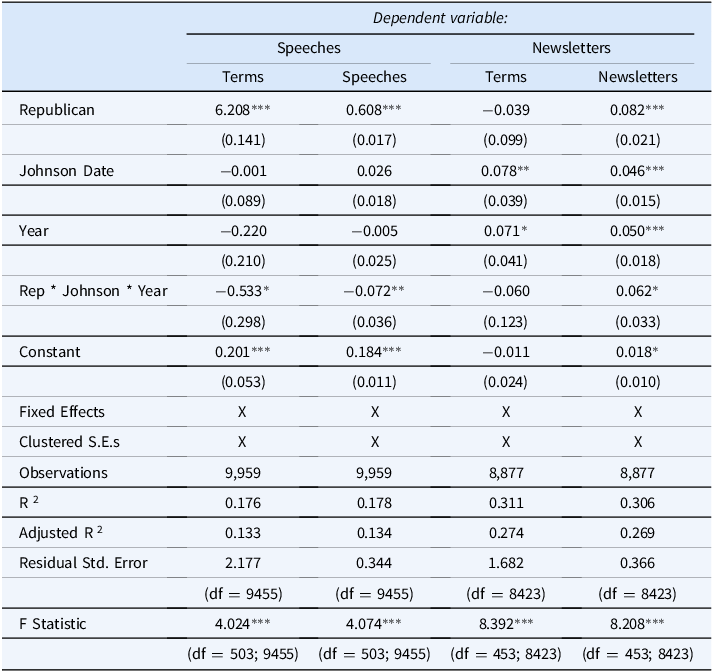

Table 2. Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences Model: Comparing the use of religious language in House speeches and newsletters

Note:

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}$

p

${{\rm{\;}}^{\rm{*}}}$

p

![]() $ \lt $

0.1;

$ \lt $

0.1;

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}$

p

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{**}}}}$

p

![]() $ \lt $

0.05;

$ \lt $

0.05;

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}$

p

${{\rm{\;}}^{{\rm{***}}}}$

p

![]() $ \lt $

0.01

$ \lt $

0.01

These regressions show that the DiD estimator—the interaction of party with the date Johnson became Speaker—is not statistically significant for either measure of religious inclusion in House speeches. While the coefficient for Republicans is large and significant (

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

), indicating that they gave significantly more religious speeches than Democrats before Johnson became Speaker, they did not increase their religious references more than Democrats did afterward. This disproves our Hypothesis 1A, which predicted a greater increase in religious rhetoric in speeches among Republicans following Johnson’s election as Speaker.

$p \lt 0.01$

), indicating that they gave significantly more religious speeches than Democrats before Johnson became Speaker, they did not increase their religious references more than Democrats did afterward. This disproves our Hypothesis 1A, which predicted a greater increase in religious rhetoric in speeches among Republicans following Johnson’s election as Speaker.

While Republicans do not shift their religious speech patterns more than Democrats, both partisan groups may have changed their religious speeches at the same rate after Johnson became Speaker. To check this possibility, we used a regression discontinuity design (RDD) to compare how often Republicans and Democrats used religion in House speeches, measured both together and separately. These regressions interacted with a binary variable of whether the speech was given before (0) or on or after Johnson became Speaker (1) with a variable indicating how many days before or after October 25 the speech was given, using the same time frame as our DiD regression. They analyzed the change in two dependent variables: the count of religious references in House speeches and the number of religious speeches. These regressions also included fixed effects and clustered standard errors for legislators and can be found in Table 3 in the Appendix.

Our RDD analysis shows that, while Democrats’ use of religious language in speeches did not significantly change after Johnson became Speaker, Republicans exhibited a notable shift. Specifically, Republicans reduced their overall use of religious terms in speeches (

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

), yet the interaction term suggests they increased the rate at which they used religious language over time (

$p \lt 0.05$

), yet the interaction term suggests they increased the rate at which they used religious language over time (

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

). However, as our post-treatment period extends through December 25th, this increase is likely impacted by the holiday season and Bible Week in mid-December, both of which likely contribute to an uptick in religious references. Overall, these results align with our DiD findings, reinforcing that Republicans did not significantly escalate religious rhetoric in House speeches after Johnson’s election as Speaker.

$p \lt 0.1$

). However, as our post-treatment period extends through December 25th, this increase is likely impacted by the holiday season and Bible Week in mid-December, both of which likely contribute to an uptick in religious references. Overall, these results align with our DiD findings, reinforcing that Republicans did not significantly escalate religious rhetoric in House speeches after Johnson’s election as Speaker.

In contrast, Republicans significantly increased their use of religious language in newsletters. Our DiD regression shows that Republicans significantly increased both their frequency of religious terms in newsletters and the number of religious newsletters compared to Democrats after Johnson became Speaker (

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

). An RDD analysis further reveals that Republicans significantly increased the number of religious terms in newsletters (

$p \lt 0.01$

). An RDD analysis further reveals that Republicans significantly increased the number of religious terms in newsletters (

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

) while Democrats significantly decreased both their religious terms in newsletters and their overall number of religious newsletters (

$p \lt 0.05$

) while Democrats significantly decreased both their religious terms in newsletters and their overall number of religious newsletters (

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

). These results, presented in Table 4 in the Appendix, are particularly notable as Johnson became Speaker before the holiday season, a time when all legislators might be expected to increase their religious rhetoric in constituent communications.

$p \lt 0.01$

). These results, presented in Table 4 in the Appendix, are particularly notable as Johnson became Speaker before the holiday season, a time when all legislators might be expected to increase their religious rhetoric in constituent communications.

The finding that Republicans significantly increased their religious messaging in newsletters but not in House speeches supports our second hypothesis: religious rhetoric in newsletters was impacted more by Johnson’s speakership than religious language on the House floor. However, this does not necessarily confirm our Hypothesis 1B regarding religious references in newsletters. The holiday season, particularly Christmas in December, may have inflated the number of religious terms following Johnson’s election in October. While the DiD framework better accounts for the holiday season than an RDD, as it directly compares partisan groups experiencing the same time period, it does not fully control for the possibility that these two partisan groups treat the holidays in different ways. For example, Republicans may be more likely than Democrats to emphasize Christianity in December. To test for this, we turn to a DiDiD test.

Difference-in-Difference-in-Differences (DiDiD)

Unlike the previous DiD model, which only accounts for the difference between two groups before and after treatment occurs, a DiDiD regression allows us to include an additional variable in our model, in this case, speeches or newsletters from the same period of the previous year. This allows us to better control for the holiday season, as we expect legislators to share similar religious (or non-religious) holiday messages as the year before.Footnote 9 Thus, our DiDiD model compares how Republican and Democratic legislators used religious rhetoric from August 25—October 24 (P1) to October 25—December 25 (P2) in 2023, and compares this with the change in religious rhetoric from August 25—October 24 (P1) to October 25—December 25 (P2) in 2022. Below is the equation for the estimator for effect of treatment for Republicans:

Our DiDiD model is very similar to our DiD model. Our independent variables are a binary variable indicating whether the legislator giving the speech is a Republican (1) or Democrat (0), a binary variable indicating if the speech is given before (0) or after October 25 (1), and a binary variable indicating if the year is 2023 (1) or 2022 (0). These variables interacted with each other. We run four separate DiDiD regressions with the same dependent variables as in the DiD regressions. We include fixed effects and clustered standard errors for legislators in all regressions. A shortened version of these regressions can be found in Table 2, with the full regression in Table 5 in the Appendix.

When analyzing the triple interacted terms in Table 2, we find that Republican representatives in 2023 used fewer religious terms and gave fewer religious speeches relative to Democrats after Johnson became Speaker, compared to the same time period in 2022 (

![]() $p \lt 0.1)$

. The positive and significant coefficients for Republicans and its interaction with the post-October 25 period (

$p \lt 0.1)$

. The positive and significant coefficients for Republicans and its interaction with the post-October 25 period (

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

and

$p \lt 0.01$

and

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

, respectively) indicate that Republicans generally used more religious terms than Democrats and increased their religious rhetoric after October 25 in both years. However, this increase was smaller in 2023 compared to 2022.

$p \lt 0.1$

, respectively) indicate that Republicans generally used more religious terms than Democrats and increased their religious rhetoric after October 25 in both years. However, this increase was smaller in 2023 compared to 2022.

Several factors may have contributed to this relative decline, such as the impact of the 2022 elections or the unusually high number of religious House speeches in October 2023. Nevertheless, after Johnson became Speaker, Republicans’ religious rhetoric did not rise as sharply as it did the previous year, resulting in a smaller gap between Republicans and Democrats in religious speech usage in late 2023 compared to late 2022.

Although religious speeches decreased after Johnson became Speaker compared to 2022, the increase in religious language in newsletters remained. After October 25, 2023, Republican representatives sent more religious newsletters than Democrats compared to the same period in 2022 (

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

), though the number of religious terms per newsletter did not change significantly. Even after controlling for the 2022 holiday season, Republicans increased their use of religious language when communicating with constituents, suggesting that Johnson influenced how they framed their outreach. However, this shift was not reflected in their House floor speeches, highlighting a distinction between how Republican representatives address their colleagues versus their constituents.

$p \lt 0.1$

), though the number of religious terms per newsletter did not change significantly. Even after controlling for the 2022 holiday season, Republicans increased their use of religious language when communicating with constituents, suggesting that Johnson influenced how they framed their outreach. However, this shift was not reflected in their House floor speeches, highlighting a distinction between how Republican representatives address their colleagues versus their constituents.

To better illustrate this, Figure 3 presents event study plots tracking the average number of partisan religious speeches and newsletters before and after October 25 in both 2023 and 2022. The plots show that after October 25, 2023, Republicans gave fewer religious speeches, whereas in 2022, their religious speech usage increased during the same period. In contrast, Republicans sent religious newsletters at a higher rate in 2023 than in 2022. Notably, Democrats did not increase their religious rhetoric after October 25, 2023, as they had in 2022, suggesting that Johnson’s speakership may have discouraged Democratic legislators from using religious language in their newsletters.Footnote 10

Figure 3. Event study plots, comparing Republican and Democratic use of religious rhetoric in House speeches and newsletters before and after October 25 in 2023 and 2022.

While most of our analyses rely on a combined dictionary of religious terms, we also ran separate DiDiD regressions for each dictionary to determine whether Johnson’s speakership influenced different religious themes. These regressions used the same independent variables as our previous DiDiD models, with the dependent variable being the number of terms from each dictionary. This resulted in six regressions, one for each dictionary, for House speeches (Table 6 in the Appendix) and six for newsletters (Table 7 in the Appendix).

Consistent with the overall decline in religious references in House speeches in 2023 compared to 2022, we find that Republican representatives used fewer Bless, Scripture, and Dogwhistle terms in speeches in 2023 compared to 2022 (

![]() $p \lt -\!.05$

,

$p \lt -\!.05$

,

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

,

$p \lt 0.1$

,

![]() $p \lt 0.01$

, respectively). In newsletters, Republicans used fewer Political terms but more Dogwhistle terms (

$p \lt 0.01$

, respectively). In newsletters, Republicans used fewer Political terms but more Dogwhistle terms (

![]() $p \lt 0.1$

,

$p \lt 0.1$

,

![]() $p \lt 0.05$

, respectively). The shift in Dogwhistle terms is particularly notable for three reasons. First, we excluded Dogwhistles from our broader religious dictionary, meaning this shift is not simply reflecting the overall decline in religious rhetoric. Second, while we do not control for specific legislative events, the simultaneous analysis of House speeches and newsletters suggests that any event influencing language on the House floor—such as an abortion bill—would likely also affect newsletter language, as legislators address these current topics with their constituents. Third, the decrease in Dogwhistle terms in speeches alongside their increase in newsletters reinforces our finding that Republican representatives adjust their language depending on their audience. While Johnson’s election as Speaker may have discouraged direct and indirect religious talk on the House floor, it appears to have encouraged more indirect religious appeals in communications with constituents.

$p \lt 0.05$

, respectively). The shift in Dogwhistle terms is particularly notable for three reasons. First, we excluded Dogwhistles from our broader religious dictionary, meaning this shift is not simply reflecting the overall decline in religious rhetoric. Second, while we do not control for specific legislative events, the simultaneous analysis of House speeches and newsletters suggests that any event influencing language on the House floor—such as an abortion bill—would likely also affect newsletter language, as legislators address these current topics with their constituents. Third, the decrease in Dogwhistle terms in speeches alongside their increase in newsletters reinforces our finding that Republican representatives adjust their language depending on their audience. While Johnson’s election as Speaker may have discouraged direct and indirect religious talk on the House floor, it appears to have encouraged more indirect religious appeals in communications with constituents.

Discussion

How does the Speaker of the House affect the religious rhetoric employed by members of Congress? Contrary to initial expectations, we found that the frequency of religious language in House speeches remained consistent or decreased in the two months after Johnson became Speaker. In contrast, we observed a significant increase in the use of religious rhetoric in newsletters sent to constituents by Republican representatives. This trend persisted even when controlling for the past holiday season.

These findings suggest that while representatives became less overtly religious when addressing each other in the House, communications to constituents grew more religious, potentially reflecting a strategic move to bolster support among voters, cue religious stereotypes, draw on the partisan nature of “God talk,” and continue to craft a “home style.” While Americans as a whole are becoming less religious (Public Religion Research Institute 2024), the recent trend towards religion within the Republican party, emphasized by Johnson’s speakership, may matter more to Republican legislators when addressing their constituents. Another possibility is that religious Republicans felt more confident in the strength of their beliefs in the House, assuming that Johnson’s leadership implicitly represented their shared values. This could have reduced the need for overt religious rhetoric in floor speeches while simultaneously emboldening representatives to emphasize religious themes more heavily in their direct communications with constituents. While Johnson’s own personal religious inclinations are evident, they may not necessarily impact representatives’ use of religious language on the House floor. Instead, his rise to power may be a reflection of broader religious and ideological trends that were already shaping congressional rhetoric.

The Democratic response further shows how Johnson’s speakership became a symbol of religious partisanship rather than a direct driver of rhetorical change. Though religious references in Democratic newsletters increased in the 2022 holiday season, a time when we would expect more religious mentions, they did not increase in 2023 after Johnson became Speaker. Given Democratic criticism of Johnson’s Christian nationalist affiliations (Walker Reference Walker2024), some Democratic representatives may have deliberately distanced themselves from religious rhetoric to avoid reinforcing partisan associations between religion and the GOP. Even if some Democrats wanted to counter Johnson’s religious rhetoric, doing so may be politically difficult. Unlike Republicans, who generally benefit from religious appeals, Democrats have a more religiously diverse (and often secular) coalition. This could make a widespread increase in religious rhetoric unlikely, as Democratic legislators may be hesitant to alienate non-religious voters. This finding further illustrates how polarization shapes political communication, reinforcing partisan divides in religious rhetoric. As Republicans increasingly link religion to their political identity, Democrats may feel pressured to downplay religious language, even if some segments of their coalition hold religious beliefs.

It is also crucial to assess how Johnson’s leadership fits within the broader ideological and religious shifts in Congress. An important consideration is that Johnson may not be the cause of religious change, but rather the culmination of a previously existing religious movement in Congress. For example, Faith Month began in 2022, a year before Johnson was elected as Speaker; in 2023, Johnson himself spoke about how “every nation would ultimately fail” without “virtues indispensably supported by religion and morality” (McPhee Reference McPhee2023). It is possible that legislators who championed religious expression in Congress were already engaged in shaping the party’s religious messaging, and Johnson’s speakership may simply have provided them with a visible leader rather than initiating new rhetorical patterns. This aligns with a broader movement toward Christian nationalism within the Republican Party, where religious rhetoric could be increasingly used as a marker of ideological alignment or a sign of support for the growing MAGA movement.

Stepping back, these results highlight the nuances in political communication. The significant difference between the use of religious language on the House floor and in newsletters to constituents suggests that representatives are acutely aware of their audience and tailor their messages accordingly. On the House floor, where speeches are part of the official record and subject to scrutiny from a wide array of stakeholders, including the media, political opponents, and a diverse public, representatives might aim to maintain a more secular tone to appeal to a broader audience and avoid controversy. Johnson’s overt religiosity could have heightened these concerns, further incentivizing representatives to decrease their religious language after he became Speaker. In contrast, newsletters to constituents are a direct line of communication between representatives and their voters, allowing for more personalized and targeted messaging. Representatives may use religious rhetoric in these communications to resonate with the specific values and beliefs of their voter base. This strategic use of religious language could be an effort to solidify voter support, particularly given the growing movement of Christian nationalism in the GOP.

We note several limitations of this study. First, the relatively short time frame of two months before and after Mike Johnson’s assumption of the Speaker role may not capture longer-term trends in the use of religious rhetoric by congresspersons. Expecting representatives to change their communication style so quickly may be unrealistic, especially given the contentious nature of Johnson’s election. Additionally, our analysis focuses on House speeches and newsletters, which do not encompass all forms of congressional communication, such as social media posts or press releases. Finally, our study does not account for other concurrent political events or external influences that might affect the use of religious rhetoric, which may potentially confound our results.

Conclusion

There are several avenues for future research. Future studies could investigate whether these rhetorical shifts are unique to Johnson’s tenure or indicative of broader patterns in congressional communication, helping to empirically test mechanisms. Research could assess whether Christian nationalist rhetoric has increased over time in both newsletters and House floor speeches. This could be done through text analysis of congressional communications across multiple sessions, identifying key phrases, themes, and sentiment associated with Christian nationalism. Comparing these trends before and after Johnson’s tenure as speaker would help determine whether his leadership accelerated an existing shift or merely reflected broader ideological trends within Congress. Furthermore, future studies could examine how religious rhetoric influences legislative behavior beyond speeches and newsletters, considering factors such as committee assignments, bill sponsorship, and voting patterns. Finally, incorporating other forms of communication, such as social media posts, press releases, and interviews, could provide a more comprehensive view of how religious rhetoric is used across different platforms.

In conclusion, this research contributes to our understanding of how congressional rhetoric adapts to political and ideological shifts in leadership. By highlighting the ways in which representatives adjust their religious messaging depending on the medium and audience, our findings showcase the strategic nature of political communication. This study also emphasizes the evolving relationship between religion and partisanship, demonstrating how religious rhetoric can serve as both a unifying tool within parties and a divisive force across party lines. As debates over Christian nationalism and the role of religion in governance and society continue, understanding these rhetorical patterns is essential for assessing how religious language influences political identity, voter perceptions, and legislative priorities in contemporary American politics.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048325100102

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers, Cammie Jo Bolin, Rebecca Glazier, and our advisors at Stanford University and George Mason University for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Lindsey Cormack for providing the D.C. Inbox data that made this project possible.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding statement

The authors received no funding or grants for this research.

Replication data

Replication data will be made available on Dataverse.org.

Julianna J. Thomson is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at George Mason University studying religious rhetoric and American politics.

Alena Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at Stanford University studying religion in American politics.