Poets and other writers have not escaped the politics of culture in post-colonial Kenya. One of our leading poets, Abdulatif Abdulla [sic], was imprisoned for three years in 1969 for writing and circulating a pamphlet: Kenya, Where Are We Heading To? Asking questions is a dangerous exercise in a post-colonial society. (Ngugi 1993: 94)

To meet Abdilatif Abdalla for the first time is to be thrilled – in the full sense of the word – by his personality and his kind, joyful and vivacious yet sensitive and respectful ways. He makes his interlocutors feel at ease when interacting with him – I have observed this on occasion with many people, including myself. At first it is hard to reconcile this fact with the knowledge that Abdalla is one of the most resilient and committed political critics of Kenyan governments, someone who has endured three years of solitary confinement in Kenya's harshest prison, and who at the same time is one of the most famous living Swahili poets. Abdilatif Abdalla is someone who acts like a brother (ndugu) to his fellow human beings.

This article requires a personal entry point as it builds on my many conversations and a developing friendship with Abdilatif Abdalla over the years. I first met him briefly during fieldwork in 1998 in Mombasa. However, we did not begin to communicate frequently until years later, when I invited his two brothers, Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir and Ahmad Nassir, to the Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) in Berlin in July 2008. I began thinking seriously about Kenya: Twendapi? and its author after Abdalla sent me a photocopy of the original pamphlet following that meeting, and especially when we were able to spend a week in Berlin talking over these and related matters in March 2010. On numerous occasions since then – be it on the phone, via Skype, or in person in Hamburg, Berlin, Mombasa or New York – Abdalla and I have discussed the personal, historical and political circumstances surrounding his early political activism.

Commentaries on the pamphlet are long overdue, given its relevance as a historical document of Kenya's early postcolonial history (beyond Abdalla's biography). My own ‘re-reading’ of the pamphlet here is only a beginning, an exercise of turning attention to the text and understanding it in its historical setting, while also indicating some possible perspectives for re-reading it today.

Thinking about Abdilatif Abdalla (who was born in 1946), a political activist and Swahili poet from Mombasa, as a ‘local intellectual’ is both stimulating and challenging. For most of his life, he has lived outside Kenya, and, as he likes to point out, he does not regard himself as an intellectual. While he underwent basic primary education in the British system in late colonial Kenya, his mind was nurtured from childhood by much exposure to, and interaction with, relatives and elders who were (in some cases highly renowned) teachers, poets, Islamic scholars, healers or politicians. And he regularly listened to lectures by scholars such as Sheikh Muhammad Kassim Mazrui and Sheikh Abdalla Saleh Farsy when staying in Mombasa. From early on he developed a knack for languages, travelling in the wider Swahili area with his guardian and great-uncle Ahmad Basheikh, a poet and teacher (who also taught him the Qur'an), living in different places and thus speaking clearly and fluently the respective ‘Viswahili’ languages (as he puts it, using the plural, to denote several distinct dialects of Swahili) – which is rare.

His thinking also builds on socialist readings and Islamic teachings (among others) and is thus shaped by trans-regional and international influences too. Prison and exile forced upon him an extreme and long-lasting spatial distance from his home region. Overall, the intellectual (thoughtful, critical) contributions he made were never determined by local norms or traditions yet were always voiced in relation to them, by means of Swahili genres and idioms of expression. What seems most highly appreciated by other Swahili scholars is his original creativity in coining words, phrases and images to think with, thus stimulating and pushing further a critical engagement with the contemporary world through the vivid capacity of language (see, for example, Bakari Reference Bakari, Beck and Kresse2016; Khamis Reference Khamis, Beck and Kresse2016; Walibora Reference Walibora, Beck and Kresse2016).

Much of this falls outside our scope here. But what we can see in Abdalla is a particular case of a mobile, morally committed and globally connected and informed thinker, whose thoughts and actions are centred around the needs (and woes) of his Kenyan peers. Throughout his life, the Swahili language has been a unique identity marker to him – a localizing feature, if you like. This links Abdilatif Abdalla to his friend and comrade Ngugi wa Thiong'o, who has often pointed to Abdalla as a comparable role model of political critique and a leading figure in African literature, also because of his insistence on raising fundamental and uncomfortable questions that need to be addressed (for example, Ngugi 1993: 94; 1998: 16–17, 105; 2009: 92–3; Reference Beck and Kresse2016).Footnote 1 The two are indeed comparable in their commitment to the moral and political struggles of their home country, and in their conviction that various forms of literary expression – including pamphlets – provide a way of engaging in these struggles while maintaining a connection to the ordinary people whose voices they seek to amplify. Both continued this work in exile from London (and elsewhere), in resilient opposition to the Moi regime.

Working with the term ‘intellectuals’ in Africa has been important to counter simplistic perceptions of African societies, and to establish, with regard to particular qualified individuals, a sense of historical agency, of internal critique, of diversity of opinions, and of the dynamics of interpretation and debate within wider shared conceptual frameworks (see, for example, Feierman Reference Feierman1990: 3–45, drawing on Gramsci). This has been applied to Muslim contexts, too, portraying coastal Somali ulama in a social-historical field of tension with regard to social and religious reform (for example, Reese Reference Reese2008: 1–32).Footnote 2 Such work is oriented towards a proper complex understanding of knowledge in society, and how it is passed on, disseminated and discussed. Local forms, systems and subfields of knowledge therefore need to be portrayed from an internal perspective on society, looking at how they are used specifically (see Lambek Reference Lambek1993). All this provides a framework for understanding intellectual practice more broadly, and for accounts of how specific genres are used in social interaction, by creative individuals for playful enjoyment, social commentary or serious political critique (see, for example, Marsden Reference Marsden2005; Barber Reference Barber2007). Around the world, intellectuals are characterized by their creativity: that is, their ability to generate original ideas that are stimulating to others, and ‘loaded with social significance’ (Collins Reference Collins1998: 6–7, 51–2).

Local intellectuals in this sense, then, are skilled performers of knowledge-related (or truth-seeking) practices who provide orientation to others and in turn have acquired recognition in their society, in African contexts often as scholars or teachers, preachers, diviners, healers, writers or poets. Keeping this social embeddedness in view is important, and one way of doing so is to focus on the specific intellectual practices that people engage in, and to contextualize them from an actor's perspective, with a view to understanding the intentions and meanings they project into what they do. Thus, the term ‘local’ may qualify the specific regionally valid contexts, webs and traditions of meaning-making within which people operate.

Abdilatif Abdalla, as a Swahili poet and political activist, is an exemplary case in point – despite the fact that he is not mentioned in an article covering dissident intellectuals in Kenya between 1964 and 2004 (Amutabi Reference Amutabi, Murunga and Nasong'o2007).Footnote 3 Mixing poetry and politics has been a continuous feature of Swahili society for a long time (see, for example, Freeman-Grenville Reference Freeman-Grenville1962; Mulokozi Reference Mulokozi1982; Amidu Reference Amidu1990), and classic historical Swahili poets such as Fumo Liyongo (c. twelfth to thirteenth century CE) and Muyaka bin Haji (1776–1840) were engaged in local politics as well as in writing (for example, Shariff Reference Shariff1991; Miehe et al. Reference Miehe and Abdalla2004; Abdulaziz Reference Abdulaziz1979). Like them, Abdalla has been embedded in his community while looking beyond it, living among his people – and separated from them, through prison and exile – as a particularly gifted and critical voice in society. This is what Swahili poets are commonly seen as: particularly knowledgeable people with a duty to speak up on behalf of their community when needed, and as a kind of moral conscience. Abdalla himself endorsed this view, considering the context of postcolonial politics.Footnote 4

In this article, I discuss Abdilatif Abdalla's early political pamphlet from 1968, Kenya: Twendapi? (Kenya: Where are we heading?) in historical context. I make reference to Kenya's political present, drawing on Abdalla's own recent statements, and lay out some core features of his thinking and intellectual practice, focusing on local contexts and normative frameworks that also mark him as a thinker from the region. As a poet, Abdalla became well known only after his term in prison (1969–72), to which he was sentenced as the author of Kenya: Twendapi? After earning his first literary recognition with a didactic poem on the Qur'anic story of Adam and Eve (Abdalla Reference Abdalla1971), he became famous with the publication of Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony), a collection of poems he had written secretly on toilet paper in prison (Abdalla Reference Abdalla1973) (see Figure 1). Using traditional genres and features of Swahili verse, Sauti ya Dhiki covered a broad range of critical topics with remarkable depth and originality: the perils of colonialism, racism, material greed and social injustice, but also abortion, loneliness, persistence, and what it means to be ‘human’. These poems were presented in such mature and yet inventive language that experts were awed by the force and scope of his verbal artistry.Footnote 5

Figure 1 Cover of Oxford University Press's 1973 edition of Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony) by Abdilatif Abdalla.

His other writings include lectures on the role of the poet in society (Abdalla Reference Abdalla, Beck and Kresse1976; Reference Abdalla, Beck and Kresse1978) and editorial work on collected poetry.Footnote 6 In addition, Abdalla has produced some important Swahili translations, including of Ayi Kwei Armah's novel The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (Reference Armah1968, translation published Reference Armah and Abdalla1975), Mahmood Mamdani's Good Muslim, Bad Muslim (Reference Mamdani2004), and a play by Vaclav Havel (Reference Havel, Abdalla and Rettova2005, with Alena Rettova).Footnote 7 All of this shows him as an influential intellectual both from and within the Swahili region. His poetry demonstrates an ongoing currency of ‘classic’ form and language, while also exemplifying two-way mediatory work between (simply put) ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ perspectives, as well as between locally grounded and internationally inspired ones. His work makes both old and new voices of Swahili poetry – as well as important Europhone literature and political commentary – accessible to a wider readership in East Africa and beyond. Indeed, despite many years in exile, Abdalla has come to occupy an important position in the Kenyan and East African intellectual landscapes.Footnote 8

Two kinds of texts – the political pamphlet and the poem – comprise Abdalla's most socially significant discursive contributions. Interrelated in the act of voicing critical thought in public, they call upon their readers to engage. As genres, they refer back to a common basis of human solidarity, qualified by the Swahili notions of haki (justice) and usawa (equality), and grounded in an overarching conception of utu (morality or humanity) that links being human with being humane.Footnote 9 As I have discussed elsewhere (Kresse Reference Kresse, Beck and Kresse2016), Abdalla's political and poetic engagements can be seen as voicing discontent in response to violations of utu, while the writer's political sensitivity and moral consciousness work as mediating features in these processes of expression. My concern is, with historical hindsight, to provide a (re-)reading of the pamphlet Kenya: Twendapi? at a time when Kenya has recently celebrated its fiftieth independence anniversary.

Today, Abdilatif Abdalla is one of the most renowned living Swahili poets. Born in Mombasa (Kuze) in 1946, Abdalla was raised by his great-uncle, Ahmad Basheikh, a prominent teacher, Qur'anic reciter and poet, who also presented his own compositions in popular weekly broadcasts on the Sauti ya Mvita (Voice of Mombasa) radio station (Brennan Reference Brennan, Hackett and Soares2015). From a young age, Abdalla read his great-uncle's new poems before they were aired and thus built up a substantial understanding of Swahili poetry – something that was augmented through the influence of his elder brother, the well-known poet Ahmad Nassir (Nassir Reference Nassir1971). Living and travelling with his great-uncle, Abdalla grew up in far-flung parts of the Swahili-speaking area: between Mombasa and the Iringa region in Tanganyika; Faza, on Pate Island in the Lamu archipelago; and Takaungu, an hour's drive north of Mombasa. He uses Kimvita, the Mombasan dialect of Kiswahili, for his poetry, and is well versed in a range of other dialects. Abdalla's family (on his mother's side) belongs to the so-called ‘Kilindini’ group of Mombasa's urban core, the ‘Twelve Tribes’ (see Berg Reference Berg1968), and further relatives include Islamic scholars, poets and healers. Well known in the region are his two elder brothers, Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir, a prominent Shii Islamic scholar and a former publisher and coastal politician, and Ustadh Ahmad Nassir Juma Bhalo, a famous poet and sought-after healer.Footnote 10 Thus, in terms of family roots and local contexts, Abdalla grew up nurturing typical intellectual skills of the region, under the influence of several local intellectuals in his family, while his formal education never went beyond year seven of primary school.

In terms of building a political consciousness, Abdalla learned much from listening to Sheikh Abdilahi, then a politician, who also directed him to specific readings from his personal library (notably Fidel Castro's speech ‘History will absolve me’). Already as a child, Abdalla was fascinated by stories about the anti-colonial Mau Mau movement led by Jomo Kenyatta (then detained). At his primary school in Takaungu, the British national anthem ‘God save the Queen’ had to be sung during the flag-raising ceremony every morning. In an interview, Abdalla recalled how he defied this and quietly sang ‘God save Kenyatta’, privately urging on the national liberation cause (ZMO 2010). This act of anti-colonial defiance by a then twelve-year-old provides an early taste of how Abdalla would later resist the authoritarian regimes of Kenyatta (as a Kenya People's Union, or KPU, member in Mombasa) and Moi (from exile in London). It is somewhat ironic that this bold-minded young opposition supporter, the same person who as a child had sung and prayed for Kenyatta's release to liberate Kenya from British colonialism, was to be detained by Kenyatta's regime. And it is even more ironic that, in 1974, about two years after his release from prison, Abdilatif Abdalla would be awarded the newly founded national Kenyatta Prize for Literature. This honour would be conferred upon him for Sauti ya Dhiki, the volume of poems he wrote while serving his prison sentence for criticizing Kenyatta in Kenya: Twendapi? Indeed, Abdalla even received a congratulatory handshake from President Kenyatta during the prize ceremony,Footnote 11 to which he travelled from exile in Tanzania.

KENYA: TWENDAPI?: TEXT AND POLITICAL CONTEXT

Kenya: Twendapi? has not yet been discussed in academic publications with due attention given to text and author,Footnote 12 nor has an English translation been published. Thus my translation (overseen by Abdalla himself and provided below) also makes accessible an important historical document of Kenya's early post-colonial history. In condemning ‘dictatorial’ (kidikteta) features of Kenyatta's KANU government, the text illustrates a fundamental turning point in Kenya's early postcolonial politics, and bears witness to the demise of democratic structures and processes that had been implemented only five years before with independence.

As for language and style, the pamphlet shows a rich and vivid use of Kimvita, the Mombasa Swahili, without mixing in any English.Footnote 13 The language is bold and assertive in casting its critique, and clear and direct in addressing the public, somewhat similar to historical dialogue poetry (such as the utenzi genre). Thus, it is accessible for the wider local audience of Swahili speakers, while not without wit and creative verbal artistry. Stinging criticism of the KANU government is put forward in explicit language, carrying heavy insults that liken KANU rulers to British colonialists, South African racists (Abdalla speaks of ‘black Boers’) and ‘barbaric’ people (-shenzi; a regional term of utmost condemnation). The language and rhetoric brim with self-confidence, and include an implicit claim to have God on one's side. Plenty of international references and invocations fill the political landscape invoked, pointing to fellow freedom fighters in Biafra and Vietnam, as well as in Zanzibar and Kenya (the Mau Mau). The pamphlet ends with a quote by Mao Zedong followed by one from John Bright, a British political reformist of the nineteenth century. Both are used to underpin the pamphlet's political demands, clad in what one may call a ‘universal’ language of human rights. The pamphlet is therefore versatile and flexible in the references it involves, and is sometimes creative (and sometimes blunt) in its intense criticism.

In November 1968, when writing Kenya: Twendapi?, the twenty-two-year-old Abdalla was an accounts clerk for the Mombasa Municipal Council. As a civil servant, he was not supposed to have party allegiances, but nevertheless had become a member of the KPU when it was founded in 1966. Started by Odinga Oginga and other disaffected KANU members, who by then considered KANU policies wrong and deeply unjust (Oginga Reference Oginga1968: 300–4), KPU was Kenya's only remaining opposition party. Kenyan politics at this time were characterized by Kenyatta's KANU regime establishing itself as the exclusive political force in the country. It created ‘a partisan state, both able and willing to eliminate opposition’, which was run by ‘an increasingly authoritarian and nepotistic governing elite’ (Hornsby Reference Hornsby2012: 156) whose main concern was to disable and quash the KPU.Footnote 14

In this political climate, Abdalla, as the designated writer among a small group of Mombasa KPU activists (who met in secret to discuss topics and contents), wrote a series of monthly KPU pamphlets critical of the KANU government. Kenya: Twendapi? was the seventh and last of these pamphlets, and the most radical of them all.Footnote 15 The pamphlets built on an ever-growing sense of frustration and disillusionment with the KANU government among ordinary citizens. Using the alias ‘wasiotosheka’ (the discontented) to sign off these texts, Abdalla picked up on Kenyatta's own choice of words, playing on the latter's use of this term to frame KPU critics as ‘disgruntled’ people who were never satisfied with the way things were (Kenyatta Reference Kenyatta1971: 18; wa Wanjiru Reference wa Wanjiru2010; ZMO 2010). These pamphlets reappropriated the term and gave it an alternative critical meaning. Indeed, the wasiotosheka became those who were justifiably discontented with what they saw happening in politics, and their discontent could be understood as a measure of the government's failure to make politics work for ordinary citizens.

The pamphlet presents an emphatic critique of the government's repression of dissent, claiming that Kenya's phase of democratic rule was over, unless the people managed to restore it from below. The concrete issue that triggered the writing of this pamphlet was the recent rejections of KPU candidates’ submissions of nominations for local government elections in 1968. It had come to be known that all submissions by candidates of the KPU were rejected, officially due to formal errors, while basically all the KANU submissions were accepted. There was a sense that instructions for this had come right from the top (Throup Reference Throup1993: 374), perhaps even being ‘ordered’ by Kenyatta himself (Branch Reference Branch2011: 64). Such tampering with the electoral nomination process made the election of KPU representatives virtually impossible. In consequence, the pamphlet accused the government of behaving even worse towards its own people than British colonial rulers had. This resonates with a recent historical assessment that calls the event ‘the most blatant abuse of all’ from among a series of KANU's political manoeuvres aimed at paralyzing and nullifying KPU influence in the country (Hornsby Reference Hornsby2012: 173).

An appeal that the pamphlet works towards is that all of Kenya's discontented citizens (wasiotosheka) needed to unite in order to change the direction Kenya was taking – ultimately, to change the government. At this point, there remained hardly any chance of a peaceful resolution to the issue, and the pamphlet implied that armed struggle was needed to bring about change. It concludes by emphasizing a readiness ‘even to die’ for one's convictions, and it formulates an awkward ultimatum towards an all-powerful and oppressive government: to return to fair politics, otherwise the time for people's action will have come (literally, basi ni hapo). Such a daring challenge to the regime could not be seen to go unpunished, and this explains why the eighteen-month imprisonment sentence imposed on the author was ultimately doubled to three years following an intervention by Attorney General Charles Njonjo.Footnote 16

The severity of the sentence corresponds to the boldness of the critique raised, and such boldness corresponds to the discontent among Kenyans after only five years of independent government. Abdalla's readiness to employ such critical language vis-à-vis Kenyatta, Kenya's liberating figure and national hero, ‘a leader whom no one could criticise’ (Throup and Hornsby Reference Throup and Hornsby1998: 11), reflects a degree of discontent and frustration that must have seemed unthinkable before. At the same time, Abdalla and his KPU peers must have reckoned with the possibility of prison (or worse) in response.Footnote 17 The threat to a dissident's life in Kenyatta and KANU's Kenya at the time can be seen in Kenyatta's own speeches given during political rallies. For instance, on ‘Kenyatta Day’ (20 October) in 1967, Kenyatta threatened KPU members in front of a large crowd. Characterizing them as ‘snakes’, he asked the audience what they did when they found a snake, and after the crowd answered, ‘We kill it!’, he called upon any KPU member present to pass this message on (Kenyatta Reference Kenyatta1968: 343–4). This can be read as giving licence to KANU supporters to harm and kill members of the KPU opposition. Such statements were apparently not uncommon (Hornsby Reference Hornsby2012: 172). Still, Abdalla and his peers were committed to voicing the critique of (many more) ‘disgruntled people’, wasiotosheka who felt disregarded by their government. Thus the critical potential of this sizeable (but largely silent) group was flagged up, and the KPU pamphlets created a discursive rallying point for the politically discontented masses – and their ‘great challenge to the government’ was taken very seriously (Branch Reference Branch2011: 62).

KENYA: TWENDAPI?: DESCRIPTION AND SUMMARY OF THE TEXT

The pamphlet itself consists of four pages of single-spaced text on A4 paper, ten paragraphs altogether (see Figure 2). The first two paragraphs draw up the need to stand up and be persistent in one's struggle against oppression. They point at multiple systematic ways in which the government has recently intensified repression, making protesting through pamphlets even more dangerous and difficult. This is why, the pamphlet explains, four months of silence had passed since the previous instalment. Yet, the pamphlet's first appeal is that one must not give up in the face of oppression, no matter how grave the suffering. A Swahili saying is used to underline that one should hold on to one's conviction: MWENYE LAKE HAWATI (literally, ‘an owner does not let go of his possession’). Subsequently, KANU's disregard for democracy is described, together with its desire to rule by force ‘forever’ (literally ‘for life’, maisha), without the approval of the citizens. The pamphlet points to the need to resist and ultimately disempower such a government. How this should be done is left open, but the pamphlet expresses that now there is no other solution than ‘to get rid of this dictatorial KANU government’ (kuiondoshea hii serikali ya KANU ya kidikteta; paragraph 2).

Figure 2 Photocopy of the title page of Kenya: Twendapi?

Paragraphs 3 to 5 specify the government's recent violations of the existent democratic electoral system to illustrate the ways in which the KPU was systematically and without legal justification obstructed from participating in the scheduled municipal elections. The pamphlet reports that all 1,800 election nomination papers submitted by KPU were rejected by electoral administrators, supposedly ‘not filled out correctly as required by the law’ – while, in contrast, among all KANU papers there was ‘not even one that had a mistake’ (paragraph 3). Furthermore, it highlights the abuses of civil servants who dropped their impartiality and ‘became like the Organising Secretary of KANU’ (paragraph 4). As an example, the District Commissioner from Machakos is cited who rejected all thirty-two papers submitted by KPU candidates in his region only after attending the KANU meeting, having previously accepted them. Such disregard for democratic principles is qualified as outrageous:

When matters reach this stage, then people are inclined to say things that in their hearts they do not like to say. Comrades, we have seen the Brit when he was ruling us. The Brit is not an African like us. Yet on top of all the evil he has done to us … still he did not dare to do what our African peers have done to us. (paragraph 6)

During colonial rule, the pamphlet says, people were made aware of such mistakes (should they have occurred) and given the opportunity to rectify them. Now people had started commenting that ‘the times of the colonial ruler were better’ (ni afadhali wakati wa Mkoloni; paragraph 6) and that KANU had taken away two fundamental rights from Kenyan citizens: the right to vote (i.e. to select a representative from two or more candidates); and their right, and indeed their actual power, to peacefully reject a government they did not support. The pamphlet rejects such undemocratic ‘democracy of the Boerish KANU government’ (paragraph 7), alluding to the practices of the South African apartheid regime.

The next section of the pamphlet (paragraph 8) picks up on the need to act upon one's discontent as a citizen, and also to rid oneself of an undemocratic and unjust government. The prospect of a (potentially armed) struggle against the government is introduced, since all ‘the appropriate and democratic means have been discarded and disregarded by those in governmental power’. At this point, the term ‘the discontented’ (WASIOTOSHEKA, in capitals) is first used to denote the critics protesting in the pamphlet. Against potential persecution by the government, they invoke just (haki) and proper (sawa) principles, emphasizing the need for all discontented citizens to unite and stand up against repression. Through unity (umoja) in action by all involved, the pamphlet states, such active resistance will be able to succeed.

Then those who tend to remain passive are appealed to with particular urgency, ‘not to fold their arms behind their backs’ (paragraph 8). The pamphlet insists that God demands active engagement from people: ‘he will not change their situation for them unless they first put some effort into changing it themselves’, building directly on a quotation from the Qur'an (paragraph 8). As things stood, change for the better was not conceivable by peaceful means alone; the pamphlet therefore implores its readers to unite in the firm conviction (imani, also ‘belief’) of doing the right thing in order to be able to act successfully:

But before we can have the ability to take this path that is not peaceful, it is necessary that we first of all have a BELIEF (not in terms of taking pity on anyone but a BELIEF [CONVICTION] that what we are doing is right (haki) and proper (sawa)). (paragraph 9)

The next section highlights the possibility of success for such an endeavour and seeks to create an air of confidence, while emphasizing that the confidence, or belief (imani), that unified people in political uprisings inspired such a degree of courage (ushujaa) among these groups that their struggles proved successful, even against all odds:

This kind of BELIEF indeed gave the Kikuyus (‘MAU MAU’) the courage to enter the forest and fight against the British, to fight for the lands and fields which they were robbed of. It was the same kind of BELIEF that helped the people of North Vietnam. BELIEF of this kind helped our brothers in Zanzibar until they were successful. And such a BELIEF indeed gave strength and courage to the people of Biafra in Nigeria – so that they keep on fighting until today. And such a BELIEF will indeed give us the strength, and the courage, to get rid of these dictatorial rulers of the KANU government. Rulers whose skin and whose faces are African, but whose hearts and actions are like those of the Boers [of South Africa; Kikaburu]. We did not expel those white Boers in order to put black Boers in their place. The time of ‘leaders in name’ [viongozi majina] is now up. Now we want ‘leaders in deed’ [viongozi vitendo]. (paragraph 9)

In the final section, then, the degree of conviction and dedication of the undersigning ‘WASIOTOSHEKA’ is emphasized, with reference to their ultimate readiness to die for their cause. Noting that everyone, especially those who are suffering, will die someday, the point is made that one should strive for a meaningful death that can bring about change. The final paragraph ends with an implicit warning to the KANU government: if there is no difference in the government's actions by the elections in 1970, ‘then that will be it …!’ (basi ni hapo …!). In conclusion, a sense of the inevitable need for armed struggle in response to the ongoing state of injustice is expressed once again.

REFLECTIONS

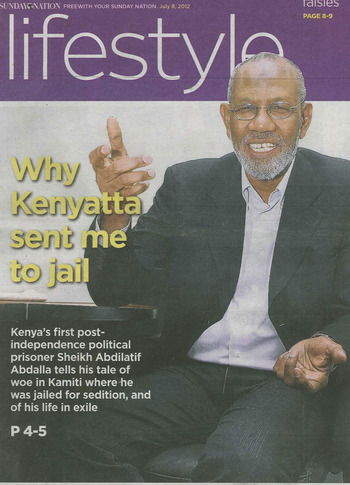

Abdalla's clear and cutting criticism of the government, as a twenty-two-year-old KPU activist, eventually landed him in jail (see Figure 3 and read the full feature article included with the supplementary materials with the online version of this article). On 20 December 1968, having been betrayed by a trusted friend and collaborator who had helped distribute the pamphlets in the Kilifi area, Abdalla was arrested by the police. He and his helpers had produced 5,000 copies by means of a manual cyclostyle machine – they secretly used the machine of the Madrasat-ul-Falah in Bondeni overnight, with the permission of its head teacher, Sheikh Mbarak bin Hiriz, a KPU sympathizer. They then posted them in public places and distributed them before dawn at significant public points and traffic nodes in and around Mombasa (for example, the Likoni ferry, Nyali Bridge and bus stations), to be picked up by commuters and passers-by.

Figure 3 ‘Why Kenyatta sent me to jail’.

When the police searched Abdalla's flat (in Kikowani), officers found one copy of the pamphlet underneath the bed in his bedroom. This constituted the only material piece of evidence against him. (Abdalla himself is unsure whether they ‘planted’ it or if he had forgotten it there, despite a thorough clean-up of his room, as a relative had tipped him off about a police move on him a week earlier.) Until the trial began in March 1969, he was detained in Shimo la Tewa prison north of Mombasa. He was not assigned any legal representative, and all attempts to secure such services, by him and by others, were frustrated. No lawyer was willing to represent him, and his suspicion that the government had intimidated all lawyers not to do so was confirmed to him much later.Footnote 18 So, Abdalla represented himself in court, and despite successfully defending himself on four counts he was not able to avoid being convicted on three others: of writing, reproducing and distributing a publication with seditious intent. He was sentenced on 20 March 1969 to eighteen months in jail. On 8 May 1969, this was doubled to three years of solitary confinement after the High Court accepted an appeal by the Attorney General about the severity of the offence (which was said to be an incitement to civil war).Footnote 19 Abdalla had to spend most of the term in Kamiti maximum security prison (where, about ten years later, Ngugi would be imprisoned), and the common practice of releasing prisoners with good conduct after completing two-thirds of their sentence was ruled out in his case. In prison, he was not allowed any visitors at all, nor was he allowed to speak to anyone – a prohibition he secretly overcame as he managed to nurture friendly relations with two of his prison guards (Abdalla Reference Abdalla1985), one of whom supplied him with a small piece of pencil with which he then secretly wrote his poems, on toilet paper.

Abdalla must have been aware of the potential consequences of wording the pamphlet in the way he did. If caught, imprisonment had to be expected in response to opposing the KANU government so fiercely. Indeed, Abdalla had been advised by his older brother and mentor, Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir, against circulating the pamphlet in its current phrasing and to alter its tone. Sheikh Abdilahi had also told him that if he proceeded with the pamphlet as it stood, he should be certain that this was really what he wanted to say. Abdalla decided to stick to the wording and to proceed along the lines he had envisaged. In hindsight, he expressed that he was happy that he had taken his decision so consciously at the time, as this helped him to endure the hardships of imprisonment.Footnote 20 A difficult family situation arose, however, when Abdalla's great-uncle Hyder Kindy, a prominent local politician, was summoned to provide official translations of Abdalla's pamphlets, to be submitted as evidence in court in the trial against him – which he did (Kindy Reference Kindy1972: 161–2).Footnote 21

On 8 May 1969, after the High Court judge announced that the government's appeal to double Abdalla's sentence would be upheld, the judge argued that the pamphlet intended ‘that the people of this country should take up arms against their lawfully elected Government and by violent means and by killings remove that Government’.Footnote 22 While, in reality, there was no explicit mention of either ‘arms’ or ‘killings’ in the pamphlet, its call for an overthrow and replacement of the government was clear. In any case, Abdalla was imprisoned for the full length of three years of solitary confinement until his release in March 1972.

KENYA: TWENDAPI? AND ITS AUTHOR TODAY: OUTLOOK AND CONCLUSIONS

In an interview in 2010, Abdalla gave the following response to the question about the ongoing relevance of the question Kenya: Twendapi?:

I would like to believe that the question is still very relevant, because I think as a nation, we have not yet sat down to seriously and thoroughly discuss what kind of country we would like Kenya to be, and also have the courage to take practical steps to bring about the structural changes needed. (cited in wa Wanjiru Reference wa Wanjiru2010)

During a keynote lecture at a Swahili Studies conference in Nairobi in August 2012, he provided a concise critique of the political elite that has been ruling in Kenya continuously since independence. He commented that, unfortunately, things have stayed the same – ‘the people are the same; the mindset is the same’ (‘watu ni walewale; fikra ni zilezile’) – but also, pointing to the common people's responsibility, that ‘we ourselves, the citizens, are to be blamed’ (‘wa kulaumiwa ni sisi wananchi wenyewe’) for having elected or accepted such rulers for such a long time. In conclusion, his comments on the ruling elite in Kenya culminated with the assertion that ‘their God is material wealth, and their religion is to oppress their fellow human beings’ (‘Mungu wao ni mali, na dini yao ni kudhulumu wenzao’).Footnote 23 Such rigid condemnation shows that, after all these years, Abdalla's sense of political injustice and his sharp and outspoken voice condemning it have remained in place – just like the basic contours of Kenya's political landscape.

The pamphlet Kenya: Twendapi? marks a turning point in standards of political practice during the early period of Kenya's postcolonial history. It responds to the erosion of democratic rule and its replacement by autocratic politics of repression. The Kenyan government at the time, and arguably today (see Cheeseman Reference Cheeseman2014: 32), would justify its repressive actions by invoking the need for ‘order’ and ‘unity’ in the country, with implicit or explicit threats to those political opponents who are portrayed as destructive elements bringing ‘dis-order’ and ‘dis-unity’ to the greater cause of the nation. This resonates with the argument about ‘disorder as political instrument’ (Chabal and Daloz Reference Chabal and Daloz1999) benefiting the ruling elites whose personal power is boosted in times of political instability. They are commonly reconfirmed and consolidated in power every time that a (real or imaginary) challenge to order has been met, and thus have an interest in keeping the spectre of potential disorder alive and present.

Historically, 1968–69 is the point in time when a long period of political silencing, intimidation and oppression took hold of the country, which lasted at least until the end of Moi's rule in late 2002, thirty-four years later. Like many other Kenyan local intellectuals who could have contributed substantially to the establishment of a democratic, open and tolerant postcolonial society, Abdalla spent all this time in prison or in exile (in Tanzania, London and Germany) while not giving up his political goals. In London especially, he worked tirelessly with Ngugi wa Thiong'o and othersFootnote 24 against the dictatorial regime of Daniel arap Moi (wa Wanjiru Reference wa Wanjiru2010), shaping democratic initiatives.Footnote 25

What kind of normative guideline could we see Abdalla following? Firstly, that practical engagement and actions (vitendo) matter; that one's actions need to follow one's insights and one's inner moral principles. ‘Defiance’, an attitude that Abdalla has emphasized in describing his actions, means insisting on the truth of one's own conviction (imani, a belief in what one does) as the paramount basis for what one is doing. Yielding to others simply because of their power is not right, when a commitment to truth and justice is to be demanded of all human beings by God. Material or instrumental justifications for one's behaviour are not acceptable, as ultimately (at the end of their life), from Abdalla's point of view, everyone has to face their creator and take responsibility for their actions, accounting for any bad deeds committed. These, then, can never be excused solely with reference to a worldly power that forces people to do (or condone) wrong. Under such circumstances, defiance, protest and criticism may be demanded from all people who draw from their moral conscience and/or their religious belief.

From this perspective, the duty of an intellectual, as someone with pronounced resources and skills of knowledge and a good insight as to how (their) society works, is to act upon one's knowledge. Among Swahili Muslims, there is a fundamental understanding that knowledge (in its different forms) should ultimately be linked to action, and that true goodness (utu) shows itself in action (kitendo) as good deeds: utu ni kitendo.Footnote 26 The knowledgeable are always embedded in practical contexts within which they need to be active (not unlike Gramsci's ‘organic intellectuals’). The task of ‘commanding right and forbidding wrong’ is at work here as a central ethical principle demanded by Islam (Cook Reference Cook2000), and this applies to intellectuals (as the knowledgeable ones) in a pronounced way. They have to make sure that they employ their abilities and resources for the benefit of society; they are obliged to educate and remind the people around them about what is good and should be done, and about what is wrong and should be avoided, or confronted and contested, in the social world in which they live using the means available to them. The implicit mutuality of a social bond of responsibility for each other (to pass on relevant knowledge) that applies to all, and thus binds all members of the community together, makes visible the social dimensions of moral obligation for intellectuals (those who have relevant insight to pass on). Within this framework, religious duty and moral duty overlap, as they are embedded within the common sociality of human life.

This is something that can be seen illustrated in Abdilatif Abdalla's actions and in his commitment to defiance as a political activist. Indeed, sticking to his imani – his convictions and his belief about what is good, right and necessary to do – no matter who the adversary (or how strong) qualifies his behaviour as morally grounded and religiously guided.Footnote 27 We can see the points raised in discussion put into practice: the relentless upholding of convictions (imani), by all means and resources, against superior powers, and in the belief (imani) that this will be successful if performed together by all the discontented citizens afflicted by social injustice. And we can see how the individual who is committed to such a conviction underlying his actions (vitendo) may not have the option of simply giving up.

As Abdalla illustrates through his actions, he has followed the obligation to stick to his convictions and face whatever consequences may follow. This he did, when writing, distributing and standing up for Kenya: Twendapi? Conceptually, we may argue that imani, as this inner moral conviction, is underpinning the sense of self for any responsible moral agent, and, in a pronounced way, for an intellectual in society. As Abdalla proves to us in his morally driven agenda for social justice and as an engaged poet and political activist, acting as a committed Muslim and socialist in orientation, a Swahili thinker and Kenyan patriot, a coastal person (mpwani) and a nationalist, a ‘man of the people’ (mtu wa watu) and a ‘voice of agony’ (sauti ya dhiki) are not mutually exclusive, but complementary aspects of being human.

And despite being far away from his home and motherland for most of his life – not of his own volition but due to the impositions of prison and exile – the concern for his people back in Kenya has remained central to his life, not least because his family continues to live there. ‘I lived in Kenya in my heart and in my thoughts’ throughout all that time, he put it to me in a conversation in 2014. He also said that his ‘whole mind was located in Kenya’,Footnote 28 to the extent that his everyday life in exile was impeded. In conclusion, this illustrates another perspective on the fundamental way in which Abdalla continued to be a local, or localizing, thinker, globally (dis)placed.Footnote 29

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

An annex following this article contains the author's annotated English translation of the Swahili pamphlet Kenya: Twendapi? by Abdilatif Abdalla followed by the Swahili text.

Further materials are available with the online version of this paper at <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0001972015000996>:

-

1 Swahili texts and English translations of three poems: ‘Kuno kunena’ (‘Speaking out’), ‘Mamba’ (‘Crocodile’) and ‘Siwati’ (‘Conviction’), all originally published in Sauti ya Dhiki (Voice of Agony, 1973).

-

2.1 Deutsche Welle radio broadcast marking Abdilatif Abdalla's retirement in 2011 as a lecturer in Kiswahili at Leipzig University (in Swahili, about 10 minutes long).

-

2.2 An English translation of the radio interview by Sara Weschler.

-

3 ‘Why Kenyatta sent me to jail’, Sunday Nation, July 2012.

-

4.1 and 4.2 Photographs of Abdilatif Abdalla and Ngugi wa Thiong'o at his retirement celebration workshop in 2011.

An extended discussion with Abdilatif Abdalla held in March 2010 at the Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) in Berlin is available at <https:// www.zmo.de/veranstaltungen/2010/Baraza_Events/Audio/Abdilatif%20Abdalla_talk.mp3>. The slot where Abdilatif Abdalla can be heard reading Kenya: Twendapi? is between 91:56 and 110:30 in this version. Alternatively, listen to Abdilatif's reading by following the link <https:// www.zmo.de/veranstaltungen/2010/Baraza_Events/BarazaEvents_2010_e.html>.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am most grateful to Abdilatif Abdalla for many hours of conversations, for his friendship and his generous availability to answer many queries, and also for his readiness to look over translation drafts. I am also grateful to Sheikh Abdilahi Nassir and Ustadh Ahmad Nassir for their guidance over the years, and for conversations on this topic. This article builds on repeated research visits to Kenya and extensive readings over the years. A very early version was presented at the IAI ‘Local Intellectuals’ panel organized by Karin Barber at the ASAUK meeting in Leeds in July 2012. Funding by DAAD, the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, the University of St Andrews, Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO), the BMBF (German Ministry of Education and Science) and Columbia University is gratefully acknowledged. Besides Abdilatif Abdalla, I also thank Karin Barber, Lutz Diegner, Mahmood Mamdani, Sara Weschler, Joy Adapon, and three anonymous reviewers for their critical reading and constructive feedback, and Sara Weschler for editorial suggestions to improve the translation and the article.

English translation of Abdilatif Abdalla's Kenya: Twendapi? (Mombasa, November 1968), by Kai Kresse in consultation with Abdilatif Abdalla, followed by the original Swahili text.

For a period of three months – since July 1968 when we released our pamphlet that we called Turuuu [See, I told you so!] until today – we have remained silent. Everyone interpreted this silence of ours in the way they wanted. One of the many interpretations given for our silence is, we have been told, ‘How come you are silent – is it that you've already been intimidated?’ To those who thought this, we say YOU MUST BE SLEEPING!! Not us. An intimidation is not something that makes one keep away from doing what one thinks is right. On the contrary, we believe that an intimidation will only increase a person's courage to continue what theyFootnote 30 are doing, provided they truly believe in it. Therefore even if, let's say, we were to be intimidated again this time, we still will not be silent. Twice before we have been intimidated. But since that day, instead of instilling us with fear, those threats have increased, and will continue to increase, our determination that what we are doing is right. For if it were not right, those with the power to intimidate people would not have gone to such trouble. Thus we say again, ONE NEVER ABANDONS WHAT ONE BELIEVES IN.Footnote 31

In this month's pamphlet, we will talk about the very shameful action carried out by the KANU government all over Kenya, in August 1968. We have no choice but to speak out about it. They did as they pleased because of the governmental powers they wield. Now, what can we, who are denied our rights and who do not have these governmental powers, do, so that we can reclaim our rights? What other means shall we employ to attain those rights when the appropriate and democratic means have been discarded and disregarded by those in governmental power? What should we do since KANU wants to ‘rule’ by force – ‘forever’Footnote 32 – without the consent of us Citizens?Footnote 33 Which path should we take in order to remove this KANU government and its dictatorial rulers, who have become increasingly more dictatorial than those who began with it [i.e. being dictatorial]? Which path could that be, fellow Citizens? What is to be done? These are the questions that a person must ask themselves. We do not know which answers you will give to these questions. But from our side we have an answer that is accepted everywhere else [in the world] where such injustices have occurred. Also, an answer like the one we are going to give you has helped all of those who have been ruled by dictators such as those in the KANU government. We will explain this answer to you later, since first we want to explain to you what brought us to the point where we will no longer consider any other way to get rid of this dictatorial KANU government, apart from the one that we will tell you about now.

Without doubt, our comrades, you have not yet forgotten those absurditiesFootnote 34 that were perpetrated by the KANU government in August – absurdities which have not been perpetrated anywhere else in the whole history of politics! Those absurdities were the trickery and treachery that the KANU government used against the opposition party of the KPU – a legally registered party just like KANU. And it is a party with more followers than KANU. These treacherous acts were committed in order that KPU not be given the opportunity to put forward their candidates in the municipal elections. What was done (as you have heard and seen) was to reject the papers of the KPU candidates because they – TAKE NOTE – ‘were not filled out correctly as required by the law’!!! Here we have a few questions that you might consider for your own judgement. Does it fit into your heads, fellow Citizens, that among the ‘submitted 1,800’ KPU papers there was not even one that was filled out correctly ‘as the law required’? Can your minds accept that among all the KANU papers there was not even a single one that had a mistake? (Or maybe theirs were filled out by demi-gods.) Such reasoning cannot be accepted even by a madman!! Or was it that the KPU leaders did not know this law about how to fill out these forms? Not possible! As we know all laws are made in parliament. Therefore, it cannot be that the representatives of KPU, who are members of parliament, did not know this law. And it also cannot be, that after KPU came to know this law that they did not follow it, as their intention was to beat KANU [in the elections]. And this was open and obvious to all! We are saying that KPU followed the law as required. And this we will prove to you when we tell you what happened in Machakos.

This indeed is the treachery of the KANU government. After the KANU government saw that those who were always in charge of accepting the submitted papers for municipal elections perhaps would not be able to unjustly reject the papers of KPU candidates, they instead put the DCsFootnote 35 in charge of receiving such papers. We are saying this based on the evidence we have, that a Town Clerk Footnote 36 of Nairobi was forced to reject the KPU papers in Nairobi, but he refused. Thereupon the local DC was put in charge. We also have evidence that the Town Clerk of Mombasa was forced to do so as well. As he did not have the guts to do so,Footnote 37 he could not decline and show courage by refusing, like his colleague in Nairobi. And you saw the result of this, dear comrades. Here we need to remind each other about one thing regarding those DCs who were appointed to receive the election papers. On 27 July 1968, there was a big meeting of all KANU leaders that took place in Nakuru. All DCs and PCsFootnote 38 of Kenya were ordered [by the government] to attend. Also, we want to explain that the DCs and PCs are actually ‘Servants of the Citizens’ (Civil Servants Footnote 39 ). And any Civil Servant is prohibited from engaging in political matters, and also from assisting any political party. Even if it is the one that formed the government. This is a democratic tradition in every country that has more than one political party. If a country has only one political party, then it becomes imperative to assist this party in any possible way. So, how come that the KANU government, which claims to follow democracy, uses Civil Servants to serve the interests of their party, KANU? Without doubt, you have seen how the Coast PC and the DC of Mombasa have actively involved themselves in politics these days. Now they are behaving like the Organising Secretary Footnote 40 of KANU and his assistant. What a travesty!!Footnote 41 What kind of democracy is this? Can't you be honest?!

Therefore, it was in Nakuru [at that meeting] that the DCs were ordered to ‘fail’Footnote 42 the KPU papers by any means possible. To substantiate that the DCs were indeed given such orders in Nakuru, we will give you just one example, from the many others that we have. For example: the papers of the contestants for the election in Machakos were received before that meeting in Nakuru took place. Since the meeting had not been held yet, 32 papers of KPU candidates were accepted. So these were filled in ‘as required by law’, as they would otherwise not have been accepted. After the Machakos DC returned from the meeting in Nakuru, he failed all these same 32 papers that he himself had passed earlier, before going to Nakuru. When it comes to this, what more is there to say? Do you see the ways in which injustice was committed?

Comrades. This is indeed what was done by the KANU government which – TAKE NOTE – is led by an African. And those to whom this was done are also Africans just like those running the government. There is nothing lacking in their Africanness.Footnote 43 When matters reach this stage, then people are inclined to say things that in their hearts they do not like to say. Comrades, we have seen the Brit[on]Footnote 44 when he was ruling us. The Brit is not an African like us. Yet on top of all the evil he has done to us, and the ways he showed his contempt and humiliated us beyond limits, still he did not dare to do what our African peers have done to us. During those [colonial] times of the British, the election papers were not failed for not being properly filled. And if you made mistakes, you were shown them and you were allowed to correct them. And on top of all this, thereafter this same paper would be accepted. What caused your election paper to be rejected was when you submitted it after the deadline. If this is how things are, well then we ‘prefer Pharaoh to Moses’. Indeed, at this point people say, about something that they preferred not to be there, that ‘the times of the colonial ruler were better’. (Give the devil his due.)Footnote 45 And when things reach this level, it feels more painful: to see an African committing such evil deeds to his fellow African, things that even the Brit, who neither cared for us nor respected us, did not do to us. But THE END OF ALL RIPE FRUIT IS TO ROT. Nothing else.

The KANU government brought this injustice upon the KPU party, since without a doubt KANU would otherwise ‘have had to eat dry rice’.Footnote 46 The KANU government knows that the people have become tired of this government. The people are tired of the barbaricFootnote 47 acts committed by this government. And for the KANU government, bringing such injustice upon KPU has in effect denied the Citizens their right to choose. This right gives the Citizen the power to elect the one who he thinks will be useful to him. (This is not how things have actually been done – somebody coming and ordering that so-and-so and so-and-so should be elected.) Also, this right to vote gives the Citizen the power to reject a government he does not want – peacefully – without using any force. But today you will see that the Citizens have been denied this right, and the KANU government has appropriated it, in order to forcefully give itself the authorization to impose on the Citizens representatives whom they do not want. Representatives who have been put in place in order to work for a certain tribe so that other tribes would be oppressed more and more. This is indeed the democracy of the BoerishFootnote 48 KANU government.

Earlier on in this pamphlet, the second question we asked was: ‘What other means shall we employ to attain those rights when the appropriate and democratic means have been discarded and disregarded by those in governmental power?’ We promised you that we would answer this question. [But] [f]irst we would like to clarify the following: – if it is true, seriously in your hearts, that you careFootnote 49 for Kenya and you love this country with all your heart (if someone feels that this is indeed their home and has nowhere else to go), and if you want equality and humanity to be realized in Kenya and the injustices to go away (since we believe that there is no one who likes to be harassed or oppressed), well then, listen carefully to what we are telling you and keep it in your minds. We (THE DISCONTENTED) we understand that we are always under surveillance. And we understand that this time especially, because of what we have just said, all possible means to silence us will be employed so that we will not continue to enlightenFootnote 50 the people any more. Also, we do understand that this time there will be another plan to make us disappear (this plan has already been tried twice in the past), but our hearts will not relentFootnote 51 even one little bitFootnote 52 because we believe that what we do and say is just and right. Also, we understand that anyone who agrees with what we are saying will be in trouble. But when the hearts of the people unite in order to do what they are determined to do, there is nothing that can defeat them. Neither imprisonment, nor even death. This is indeed common everywhere in the world where there are people who are ready to sacrifice themselves and endure all the troubles for the sake of saving their fellow human beings, who will live on after them. When unified in heart, thought and belief,Footnote 53 we will succeed without a doubt. Not even once will we agree to keep quiet for fear of being persecuted, since the KANU government continues to oppress people in such ways. Also, we ask our fellow Citizens not to fold their arms behind their backs, expecting that things will change without us ourselves putting effort into changing them. Nor should we agree with attitudes like those of other people, saying ‘God will remove this for us’. It is true that it is not difficult for God to do this; but God himself has told human beings he will not change their situation for them unless they first put some effort into changing it themselves.

Fellow Citizens. The answer to the question we have been asking above is the following. Since peaceful means of removing the government – namely, by the ballot – are already being choked offFootnote 54 by the KANU government ahead of the bigFootnote 55 elections in 1970, and since the KANU government has committed such dirty acts as those we have seen, well then, there is no remedy or alternative peaceful way to remove this government. But before we can have the ability to take this path that is not peaceful, it is necessary that we first of all have a BELIEF (not in terms of taking pity on anyone but a BELIEF [CONVICTION] that what we are doing is right and proper). This kind of BELIEF indeed gave the Kikuyus (‘MAU MAU’) the courageFootnote 56 to enter the forest and fight against the British, to fight for the lands and fields which they were robbed of. It was the same kind of BELIEF that helped the people of North Vietnam. BELIEF of this kind helped our brothers in Zanzibar until they were successful. And such a BELIEF indeed gave strength and courage to the people of Biafra in Nigeria – so that they keep on fighting until today. And such a BELIEF will indeed give us the strength, and the courage, to get rid of these dictatorial rulers of the KANU government. Rulers whose skin and whose faces are African, but whose hearts and actions are like those of the Boers. We did not expel those white Boers in order to put black Boers in their place. The time of ‘leaders in name’ alone is now up. Now we want ‘leaders in deed’.

It is true that taking this path is no mean task nor is it easy. It is a matter that requires us to give our sweatFootnote 57 if we want to succeed. There is nothing that can save human beings from death. Everywhere where there is protest and liberation struggle there will necessarily be deaths. All human beings have to die, but there are two types of death. As one famous activistFootnote 58 once said, ‘even though death will reach every human being, there is a death as heavy as a rock and one as light as a feather’. There are still some days left. Let's wait for 1970 and see what happens. If things turn out to be as they were in August this year, or as they were in 1966, well then that will be it….!Footnote 59

“LONG DELAYED JUSTICE OR LONG CONTINUED INJUSTICE PROVOKES THE EMPLOYMENT OF FORCE TO OBTAIN REDRESS”

- J.B.Footnote 60NOVEMBER 1968 THE DISCONTENTED

MOMBASA

Kwa muda wa miezi mitatu tangu mwezi wa Julai 1968 tulipotoa karatasi yetu tuliyoiita Turuuu, mpaka hivi leo – tulikuwa tumenyamaa kimya. Kila mtu alikitafsiri kimya chetu hicho alivyotaka mwenyewe. Moja katika tafsiri nyingi zilizopawa kimya chetu ni tuliambiwa, “Mbona mu kimya, au munshatishwa?” Wale ambao walikuwa wakifikiri hayo twawaambia, MUNLALA!! Sio sisi. Kitisho sicho kimfanyacho mtu kuacha kufanya lile aaminilo kuwa ni sawa. Bali sisi twaamini kitisho huzidi kumpa mtu ushujaa wa kuendelea na lile alifanyalo. Bora awe ataliamini kisawasawa! Kwa hivyo hata, tuseme, tukatishwa tena, pia hatutanyamaa. Mara mbili za mwanzo tulitishwa. Lakini tangu siku hiyo badili ya vitisho hivyo kututia uwoga, vimezidi na vitazidi kututhubutishia kuwa tufanyalo ni la haki. Kwani kama si la haki, hao wenye uwezo wa kutisha watu wasingejipa tabu yote hiyo. Twasema tena kuwa MWENYE LAKE HAWATI.

Katika karatasi ya mwezi huu tutazungumza juu ya jambo la aibu kupita kiasi ambalo lilifanywa na sirikali ya KANU Kenya nzima, katika mwezi wa Agosti 1968. Hatuna budi na kulisema. Wao walifanya walivyopenda kwa kujivunia kwamba wana nguvu za kisirikali. Jee sisi ambao twanyimwa haki zetu, na ambao hatuna hizo nguvu za kisirikali, tutafanyaje hata tuzipate hizo haki zetu? Ni njia gani nyengine inayofaa kutumiwa ili haki hizo zipatikane maadamu njia za sawa sawa na za kidemokrasi zimetupiliwa mbali, na wala hazijaliwi, na hao walio na nguvu za kisirikali? Ni jambo gani tutakalofanya maadamu KANU yataka “kutawala” kwa nguvu – “maisha” – bila ya idhini yetu Wananchi? Ni njia gani tutakayopita ili tuiondoshe hii sirikali ya KANU na watawala wake wa kidikteta, ambao wameupitisha mpaka udikteta wao kuliko hao wenyewe waliouanza? Ni njia gani Wananchi wenzetu? Ni lipi la kufanywa? Hizo ndizo suala ambazo mtu ataka ajiulize. Sisi hatujui mutazipa jawabu gani suala hizo. Lakini upande wetu sisi tunayo jawabu ikubaliwayo kila mahali ambapo mambo ya dhulma namna hii yamepata kutokea. Vile vile, jawabu kama hiyo tutakayowapa, imewasaidia kila waliokuwa wametawaliwa na madikteta mfano kama hawa wa sirikali ya KANU. Jawabu yetu hiyo tutawaeleza baadaye, kwani mwanzo twataka kuwaeleza lililotufanya sisi kutoifikiria njia nyengine ya kuiondoshea hii sirikali ya KANU ya kidikteta, isipokuwa hiyo tutakayowaeleza.

Bila ya shaka, ndugu zetu, vile vioja vilivyofanywa na sirikali ya KANU katika mwezi wa August, bado hamjavisahau. Vioja ambavyo havijafanyika mahali popote katika historia nzima ya siasa! Vioja vyenyewe ni hikima na hila ambazo sirikali ya KANU ilikitumilia chama cha upinzani cha KPU – chama ambacho ni cha halali kama kilivyo hicho cha KANU. Na ni chama chenye wafuasi wengi zaidi kuliko KANU. Hila hizo zilifanywa ili kutoipa KPU nafasi ya kusimamisha wajumbe wake ili kupigania uchaguzi wa Manispaa. Hila zilizofanywa (kama mulivyosikia na mulivyoona) ni kutozikubali karatasi za wajumbe wa KPU kwa kuwa ATI “hazikujazwa sawa sawa kama sharia itakavyo”!!! Sisi hapa tuna masuala machache ambayo nyinyi ndio mutakaohukumu. Yaingia katika akili, Wananchi wenzetu, kuwa katika karatasi za KPU “zipatazo 1,800” ikawa haikupatikana hata moja ambayo ilijazwa sawa sawa “kama sharia itakavyo”? Akili zenu zaweza kukubali kuwa katika hizo karatasi za KANU haikupatikana hata moja ambayo ilikuwa na makosa? (Au labda zao wao zilijazwa na Miungu-watu). Sababu namna hizi haziwezi kukubalika hata na mwandazimu!! Au walikuwa viongozi wa KPU hawaijui hiyo sharia ya kujazia fomu? Haimkiniki! Tujuavyo sisi ni kuwa sharia zote hutungwa bungeni. Kwa hivyo, haiwezekani kuwa iwe wajumbe wa KPU, ambao wamo ndani ya bunge, wakawa hawakuijua sharia hiyo. Na pia haiwezekani, baada ya kuwa KPU walikuwa wakiijua sharia hiyo, wakawa hawakuifuata, hali ya kuwa nia yao ilikuwa ni kuishinda KANU. Na hilo lilikuwa wazi kabisa! Sisi twasema kuwa KPU iliifuata sharia kama itakikanavyo. Na tutawathubutishia hilo tukiwaeleza yaliyotukia Machakos.

Hiyo ndiyo hila ya sirikali ya KANU. Baada ya sirikali ya KANU kuona kuwa wale ambao siku zote ndio wenye dhamana ya kuzipokea karatasi za uchaguzi wa Manispaa pengine hawataweza kuzikataa karatasi za wajumbe wa KPU kwa kutumia dhulma, badili yake waliwekwa maDC ili wawe ndio wapokeaji wa hizo karatasi. Twasema hivyo maana tunao ushahidi kuwa Town Clerk wa Nairobi alilazimishwa kuzifelisha karatasi za wajumbe wa KPU wa Nairobi, lakini alikataa. Ndipo akawekwa DC wa hapo. Vile vile tunao ushahidi wa kuonyesha kuwa Town Clerk wa Mombasa pia alilazimishwa afanye hivyo. Kwa moyo wake mdogo hakuweza kurudi nyuma na kuonyesha ushujaa wa kukataa kama mwenzake wa Nairobi. Na matokeo yake muliyaona ndugu zetu. Hapa yataka tukumbushane jambo moja kuhusu hao maDC waliowekwa kuwa wawe ndio wapokeaji wa karatasi za uchaguzi. Tarehe 27 Julai 1968, kulikuwa na mkutano mkubwa wa viongozi wote wa KANU uliofanywa Nakuru. Katika mkutano huo, maDC na maPC wote wa Kenya waliitwa kwenda kuhudhuria. Vile vile, hapa twataka tufahamishane kuwa maDC na maPC ni Watumishi wa Raia (Civil Servants). Na Mtumishi wa Raia yoyote hana ruhusa kuingilia mambo ya siasa, wala kusaidia chama chochote cha siasa. Hata kama ndicho kilichounda sirikali. Hii ni dasturi ya kidemokrasi katika kila nchi ambayo ina vyama vya siasa zaidi ya kimoja. Ikiwa ni nchi yenye chama kimoja tu cha siasa, hapo huwa ni lazima Watumishi wa Raia kukisaidia chama hicho kwa kila njia. Sasa ni vipi, basi, ikawa sirikali ya KANU, ambayo yajidai kuwa yafuata demokrasi ikawa itatumia Watumishi wa Raia kuwapelekea shughuli za chama chao cha KANU? Bila ya shaka mushapata kuwaona PC wa Pwani na DC wa Mombasa walivyojitia katika siasa siku hizi. Sasa wamekuwa ni kama Organising Secretary wa KANU na msaidizi wake. Vituko vikubwa hivi!! Demokrasi ya sampuli gain hii? Hamusemi kweli!?

Basi huko Nakuru ndiko walikokwenda pawa amri maDC kuwa ni lazima wazifelishe karatasi za KPU kwa njia yoyote itakayowezekana. Ili kuwathubutishia kuwa maDC walipawa amri hizo huko Nakuru, tutawapa mfano mmoja tu, katika mingineyo mingi tuliyonayo. Kwa mfano: karatasi za wapiganiaji uchaguzi wa Machakos zilipokelewa kabla ya huo mkutano wa Nakuru. Kwa kuwa mkutano huo ulikuwa haujafanywa, karatasi za wajumbe 32 wa KPU zilikubaliwa. Kwa hivyo zilijazwa “kama sharia itakavyo”, kwani zisingepasishwa. Baada ya DC wa hapo kurudi huko mkutanoni Nakuru, alizifelisha hizo karatasi zote 32 ambazo yeye mwenyewe ndiye aliyezipasisha kabla ya kwenda Nakuru.Yakifika hapa husemwaje? Mwaziona namna dhulma zilivyotumika?

Ndugu zetu. Hayo ndiyo yaliyofanywa na sirikali ya KANU ambayo ATI yaongozwa na Muafrika. Na waliofanyiwa hayo ni Waafrika sawa na hao waiongozao sirikali. Hawakupungukiwa na chochote katika Uafrika wao. Mambo yafikapo namna hii, ndipo mtu asemapo maneno ambayo moyo wake haupendi kuyasema. Ndugu zetu, tumemuona Muingereza alipokuwa ametutawala. Muingereza si Muafrika mwenzetu. Na juu ya uovu wake wote aliotufanyia na kutudharau kwake kote kupita kiasi, pia hakusubutu kutenda kama haya tutendwayo na Waafrika wenzetu. Wakati huo wa Muingereza, karatasi za uchaguzi zilikuwa hazifelishwi kwa kutoandikwa sawa sawa. Na ilikuwa iwapo umefanya makosa ulikuwa ukioneshwa makosa yako na ukaruhusiwa kuyasahihisha. Na juu ya yote hayo, halafu karatasi hiyo hiyo ilikuwa ikipasishwa. Jambo lililokuwa likisababisha kukataliwa karatasi yako ya uchaguzi lilikuwa ni iwapo umeipeleka baada ya saa zilizowekwa kwisha. Ikiwa mambo ni namna hii, basi “afadhali ya Firauni kuliko ya Musa.” Ndipo hapa mtu asemapo jambo asilolipenda kuwa, “ni afadhali wakati wa Mkoloni.” (Mgala muuweni na haki mpeni). Na mambo yafikapo hapa ndipo yaoneshapo uchungu zaidi: kumuona Muafrika yuwamtenda visa Muafrika mwenzake ambavyo hata Muingereza asiyetujua mwanzo wala mwisho hakututendea. Lakini MWISHO WA MBIVU NI KUOZA. Hakuna zaidi ya hapo.

Sirikali ya KANU ilikitumilia chama cha KPU dhulma hizo, maana bila ya shaka KANU ingeula wali mkavu. Sirikali ya KANU yajua kuwa watu wamechokeshwa na sirikali hii. Watu wamechokeshwa na vitendo vya kishenzi vifanywavyo na sirikali hii. Na kwa sirikali ya KANU kukitumilia KPU dhulma hizo imesababisha kuwanyima Wananchi haki yao ya kupiga kura. Haki hii ndiyo impayo Mwananchi nguvu za kumchagua yule amfikiriye kuwa ndiye atakayekuwa na manufaa naye. (Sio hivi yalivyofanywa – kuja mtu akatoa amri kuwa Fulani na Fulani wawe ndio). Vile vile haki hii ya kupiga kura ndiyo impayo Mwananchi nguvu za kuiondoshea sirikali asiyoitaka – kwa amani – bila ya kutumia nguvu. Lakini leo mutaona kuwa haki hii wamenyimwa Wananchi na imechukuliwa na sirikali ya KANU, kwa kujipa idhini ya kinguvunguvu, ya kuwachagulia Wananchi wajumbe wasiowataka. Wajumbe ambao wamewekwa ili kulifanyia kazi kabila Fulani ili lizidi kudhulumu makabila mengine. Hii ndiyo demokrasi ya sirikali ya KANU ya kikaburu.

Mwanzo mwanzo wa karatasi hii, suala ya pili tuliyoiuliza ni hii: “Ni njia gani nyengine inayofaa kutumiwa ili haki hizo zipatikane maadamu njia za sawa sawa za kidemokrasi zimetupiliwa mbali na wala hazijaliwi na hao walio na nguvu za kisirikali?” Tuliwaahidi kuwa sisi tutaijibu. Mwanzo twapenda tufahamishane yafuatayo: – Ikiwa kweli, kwa dhati ya nyoyo zenu, mwaionea uchungu na kuipenda nchi ya Kenya (ikiwa mtu yuwaamini kuwa hapa ndipo kwao na hana pengine pa kwenda), na ikiwa mwapenda usawa na ubinaaadamu ufanyike Kenya na dhulma ziondoke (kama tuaminivyo kuwa hakuna akubaliye kuonewa wala kudhulumiwa), basi yasikizeni sana haya tuwaambiayo na muyatie akilini mwenu. Sisi (WASIOTOSHEKA) twafahamu kuwa siku zote hizi twafuatwa. Na twafahamu kuwa haswa safari hii, kwa kuwa tumesema maneno haya, tutatafutiwa kila njia ya kunyamazishwa ili tusiendelee kufunua watu macho zaidi. Vile vile twafahamu kuwa safari hii utakuwako mpango mwengine wa kutuzamisha (mpango huo umejaribiwa mara mbili zilizopita), lakini nyoyo zetu hazitarudi nyuma hata chembe, maadamu twaamini kuwa tufanyalo na tusemalo ni haki na ni sawa. Vile vile twafahamu kuwa kila atakayekuwa akikubaliana na sisi kwa maneno yetu tusemayo, pia naye atapatishwa tabu. Lakini nyoyo za binaadamu zikiungana ili kufanya walilokusudia, hakuna kiwezacho kuzishinda. Licha kifungo hata kifo. Ndiyo dasturi ya kila mahali duniani, kuwako watu ambao wako radhi kupata tabu wao lakini wawasalimishe wenzao watakaobakia. Kwa moyo mmoja, kwa fikira moja, na kwa imani moja, bila ya shaka tutafaulu. Hata mara moja hatutakubali kunyamaza kimya kwa kuogopa kuadhibiwa, maadamu sirikali ya KANU yaendelea kuwafanyia watu dhulma namna hii. Kadhalika twawaomba Wananchi wenzetu wasikubali kufunga mikono yao nyuma kwa kutarajia kuwa mambo yatabadilika bila ya sisi wenyewe kufanya bidii na kuyabadilisha. Wala tusikubali kuwa na tabia kama ile ya watu wengine, ya kusema kuwa “Mngu atatuondoshea.” Ni kweli kuwa si kazi kubwa kwa Mngu kufanya hilo; lakini yeye mwenyewe Mngu amewaambia binaadamu kuwa hatawabadilishia hali yao mpaka mwanzo binaadamu wenyewe wajibidiishe kuibadilisha.

Wananchi. Jawabu ya suala tuliyoiuliza hapo mbele ni hii. Maadamu njia ya amani ya kuiondoshea sirikali – yaani ya kupiga kura, – yaanza kuuliwa na sirikali ya KANU kabla ya uchaguzi mkubwa wa 1970, na maadamu sirikali ya KANU ina vitendo vichafu kama hivi tuvionavyo, basi hakuna dawa wala njia nyengine ya amani ya kuiondoshea sirikali hii. Lakini kabla ya kuwa na uwezo wa kutumia hiyo njia isiyokuwa ya amani, ni lazima mwanzo tuwe na IMANI (siyo ya kumhurumia mtu), bali ni IMANI ya kuamini kuwa tutakalofanya ni haki na ni sawa. IMANI namna hii hii ndiyo iliyowapa nguvu Wakikuyu (“MAU MAU”) kuingia misituni na kupigana na Muingereza kwa kupigania ardhi na mashamba yao waliyokuwa wamenyang'anywa. IMANI namna hii hii ndiyo iwasaidiayo watu wa Vietnam ya Kaskazini. IMANI namna hii hii ndiyo iliyowasaidia ndugu zetu wa Zanzibar mpaka wakafaulu. Na IMANI kama hii ndiyo iliyowapa nguvu na ushujaa jimbo la Nigeria lililojitenga – Biafra – wakawa mpaka leo bado waendelea kupigana. Na IMANI kama hiyo ndiyo itakayotupa nguvu sisi, na ushujaa, wa kuwaondoshea hawa watawala wa kidikteta wa sirikali ya KANU. Watawala ambao ngozi zao na nyuso zao ni za Kiafrika, lakini nyoyo zao na vitendo vyao ni vya Kikaburu. Hatukuwaondoa Makaburu weupe ili tuweke Makaburu weusi. Wakati wa “viongozi majina” sio tena huu. Sasa twataka “viongozi vitendo.”

Ni kweli kuwa kutumia njia hiyo si kazi ndogo wala si rahisi. Ni jambo ambalo litatubidi tutoe jasho letu, ikiwa twataka tufaulu. Hakuna jambo liwezalo kumsalimisha binaadamu na kifo. Kila penye utetezi na ukombozi, ni lazima kuwe na vifo. Watu wote ni lazima kufa, lakini kuna daraja mbili za kifo. Kama alivyosema mtetezi mmoja mkubwa kuwa, “Ingawa kifo kitamfika kila binaadamu, lakini kuna kilicho kizito kama jabali na kuna kilicho chepesi kama unyowa.” Siku bado zikaliko. Tuyangoje ya 1970 tuyatizame. Ikiwa mwendo utakuwa ni kama ulivyokuwa August mwaka huu, na kama ulivyokuwa 1966, basi ni hapo….!

“HAKI INAYOCHELEWESHWA KUTIMIZWA, AU DHULUMA

ZIENDELEAZO KWA MUDA MREFU, HUSABABISHA

KUTUMIWA NGUVU ILI KULETA NAFUU.”

- J.B.NOVEMBER 1968 WASIOTOSHEKA

MOMBASA