It was the autumn of 1745, and the provincial bureaucracy had mobilized itself for a burst of adulation. The Jiangxi governor Saileng’e 塞楞額 was the author of record of one of the broadly similar effusions thanking Hongli, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1735–1796), for celebrating the tenth anniversary of his accession to the throne with a one-year remission of the land tax, which was the Qing state’s staple source of public revenue. “Rich reserves are to be stored under poverty-stricken eaves,” noted Saileng’e; “down to the very coasts, rejoicing hearts will be in great accord.” His language echoed an ancient cliché to the effect that riches are best “stored within the population,” thereby chiming in with the public-policy rationale for the tax remission that had been stated in the imperial edict announcing it. “There is only so much wealth in the world,” declares the edict, in wording adapted from a much-misquoted eleventh-century dictum; “if it is not concentrated above, it will be dispersed below”—and where better to deposit it than under the eaves of humble cottagers, the very people whom the benevolence of the ideal Confucian monarch was supposed to favor?Footnote 1

It is tempting to take the references to public-policy economic rationales in some eighteenth-century edicts announcing gestures of imperial munificence as indicating the framework in which these gestures are properly discussed. In claiming that tax remissions in general—including the much more common local and regional exemptions granted in the wake of natural disasters—contributed to “raising farmers’ enthusiasm for production, stabilizing society and promoting socioeconomic prosperity and the formation of the Qianlong golden age,” the PRC historian Chang Jianhua 常建華 was applying common sense. He assumed that fiscal sacrifice on the Qing state’s part had real-world impacts, and that those impacts tended towards society’s enrichment. To claim—as is plausible—that it was predominantly landlord society that was enriched by universal tax remissions is still to focus on socio-economic outcomes.Footnote 2 In this essay, by contrast, I show that the economic argumentation in a series of such edicts was weak even at its early best and became increasingly attenuated as the eighteenth century wore on. The theme that largely replaced it was that of dynastic succession in dynastic time—a time that was marked off by those anniversaries that the reigning monarch chose to elevate. Zhang Taisu has argued that the intensifying Sino-Manchu tendency to under-tax the agrarian sector was caused by the ruling establishment’s embrace of a set of “ideological” beliefs about over-taxation and its risks.Footnote 3 By contrast, the story told below of zero-taxation episodes shows economic ideology in a subsidiary enabling role, the main impetus coming from the reigning emperor’s political ambition and interpretation of the rights of empery.

Declaration of an act of extraordinary fiscal munificence was itself an act of self-positioning within dynastic time and thereby part of what Peter Burke has called the “fabrication” of the monarchical and indeed imperial persona.Footnote 4 Whom was the self-positioning intended to impress? I use an eccentric comparison—between Hongli and his grandfather’s contemporary Louis XIV (r. 1643–1715)—to propose a reading of the fiscally most irresponsible of the universal tax remissions in terms of a young monarch’s desire for self-actualization, a concept borrowed from a well-known psychological paradigm.Footnote 5 The adulation from the provinces disguised the real purpose of the gesture. Who knew for sure that humble cottagers would benefit? I further argue that it was his own entourage of senior metropolitan bureaucrats whom Hongli’s self-assertion was intended to impress. The irony in the story lies in the contrast between Hongli’s conduct and that of the grandfather: Xuanye, the Kangxi emperor (r. 1661–1722), the model whom Hongli claimed to be emulating in his first two extravaganzas of generosity to taxpayers.

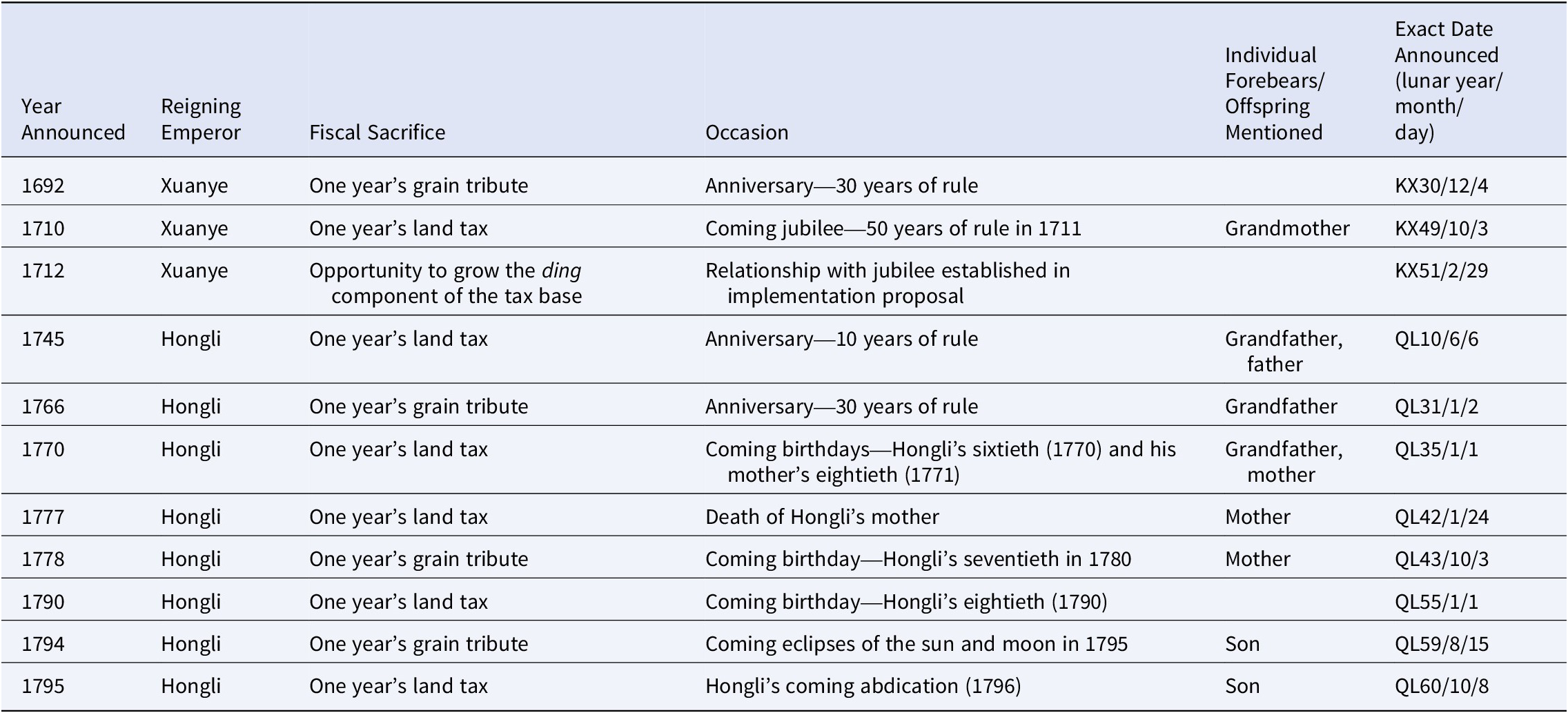

Table 1 lists the eleven high-Qing acts of extraordinary munificence to be considered in this article. Only the first three were ordered by Xuanye, and one of these differed from all the others: the famous decision of 1712 to freeze the ding 丁 (“fiscal individuals”—nominally adult males liable for unpaid service to the state) component of the tax base, a familiar story that I retell for what it brings to our understanding of the ageing Xuanye as elder-statesman emperor.Footnote 6 The other eight were ordered by Hongli. Four of the eleven were one-year remissions of the supplementary grain tax, the so-called “grain tribute,” that was levied from eight provinces to feed the metropolitan establishment; six were one-year remissions of the far more important land tax, levied in all eighteen provinces of China proper and more precisely termed “the land and fiscal individuals tax.” During the six decades from 1692 to 1751, there was one of these extraordinary acts of grace on average every fifteen years; during the five decades from 1752 to 1801, the frequency was almost one every seven years. There was also a change in the nature of the special occasions that were honored with extraordinary acts of fiscal grace, with public regnal anniversaries—the celebration of thirty, fifty, and even ten years on the throne—being largely replaced by personal birthdays (Hongli’s and his mother’s). There were exceptions to this pattern: a conscious intent to celebrate an anniversary is not articulated in the earliest remission edict, the 1777 remission announcement was in response to Hongli’s mother’s death, and the last two acts of grace were occasioned by adverse celestial portents and Hongli’s coming abdication in favor of his son. These exceptions do not compromise the overall picture of eventual monarchical appropriation of the power to tax—or, in this case, abstain from taxing—to commemorate lifecycle milestones within the royal family.

Table 1. Acts of Extraordinary Fiscal Munificence by High-Qing Emperors

Sources: edicts transcribed in the Qing shilu and Shangyu dang and cited in the discussion below.

None of this may seem scandalous or surprising. The exchequer was rich in Hongli’s last decades, when in any given year the central government was likely to have at least a 70-million-tael silver stockpile of public funds under its direct control. The income sacrifice entailed by extraordinary tax remissions was always spread over a number of years—three in the case of the universal land-tax remissions. As He Ping has noted, a yearly sacrifice of roughly 9.3 million taels would have been only 13.3% of a 70-million-tael reserve—even less when the stockpile was larger. Year-end balances occasionally reached 80 million taels during the 1770s, after which the record has more gaps than figures.Footnote 7 That Hongli invested heavily in spectacular displays of filiality towards his mother is common knowledge.Footnote 8 That the magnificent façade of late-Qianlong governance masked general stagnancy and pervasive corruption has been the conventional understanding since the reign of Hongli’s successor. Benign as the consequences for taxpayers may seem, the ageing Hongli’s diversion of public fiscal powers to the celebration of private ruling-house anniversaries is consistent with the notion that he presided over a decline in Qing political culture, a cliché that this article leaves unchallenged.

Attention focuses instead on the one universal land-tax remission that constituted a significant fiscal risk: that announced in 1745, when treasury reserves were exceptionally limited by high-Qing standards, and the Qing state was just embroiling itself in border wars that turned out costlier than expected. I have elsewhere examined both the challenges of the fiscal context and the Board of Revenue’s ingenious management of the rotation of the year of benefit among the eighteen provinces in such a way as to minimize the damage to the budgets that mattered most: those for paying the armed forces that were garrisoned in the provinces and underwrote Manchu control of China.Footnote 9 Here, by contrast, I explore the political dynamics of Hongli’s gamble with state finance at the midpoint of the century-long history of high-Qing munificence extravaganzas. I hope to offer not only a plausible reconstruction of his motivation but also insight into the transition from a polity in which an ageing grandfather naively sought to use state fiscal powers to address a perceived socioeconomic problem to one in which his ageing grandson used those powers to stimulate recognition that the throne’s birthday occupant was a jolly good fellow.

This article has three parts. I first review the edicts that announced the acts of grace in just sufficient detail to confirm the patterns sketched above.Footnote 10 Scrutiny of some of the provincial outpourings of gratitude for the 1745 universal land-tax remission then provokes questions about the real value of that gesture from a public-policy perspective. A comparison between Hongli and Louis XIV at similar stages in their regnal lifecycles finally introduces an explanation of the rashness of the 1745 initiative in terms not only of self-actualization but also self-differentiation from the relative most absent from the edicts: Hongli’s father Yinzhen, the Yongzheng emperor (r. 1722–1735).

Monarchical Munificence on Textual Display

The edict of the twelfth moon of Xuanye’s thirtieth lunar year as emperor (1691–92) announcing the staggered remission of the grain tribute over the following few years was surely not intended to found a tradition of celebrating imperial anniversaries with such acts of grace. A directive to the Board of Revenue on a matter on which Xuanye had initiated discussion three days earlier, it began with a formulaic evocation of Xuanye’s diligence in planning for his subjects’ well-being throughout his thirty years of rulership. This edict can be taken at face value as a considerate ruler’s response to an over-abundance of tribute grain in the metropolitan granaries at a time when regular alternatives to leaving surplus stores to rot were still being established. Xuanye admitted his error when the Nine Ministries Assembly pointed out the serious impact that his original plan—reallocating much of the tribute due for delivery in 1692 to important southerly garrison cities and remitting that due in 1693 altogether—would have on Beijing’s grain market, where a significant proportion of the tribute grain was eventually traded. His edict of 21 January 1692 outlined the more prudent course of action to which the Assembly had guided him.Footnote 11

By contrast, the florid, lengthy edict promulgated on 23 November 1710 to announce the universal land-tax remission that was to be spread over the 1711–13 triennium can reasonably be read as occasioned by the coming jubilee. Xuanye had acceded in February 1661, but his years on the throne were officially numbered from the first day of the lunar year (1662–63) when his reign-title Kangxi came into use. The passage of concern here reads:

In Our recent periodic tours, We have traversed seven provinces and attained a comprehensive knowledge of the customs of the people north and south and of their daily needs and means of livelihood. The reason why the people’s livelihood is less than fully opulent is truly that, with the protracted peace, the population has grown daily more profuse. Given that the amount of land does not increase, nor does production, it stands to reason that, inevitably, the food supply runs short. As Our gaze penetrated this distress, We were constantly in profound cogitation, on which we unstintingly spread forth benevolence in order to revive the people’s strength. Next year is the fiftieth of [this Our] Kangxi reign. [As a way of sending forth] further torrents of abounding grace wherewith to reach our people, We were minded to remit all of the realm’s [land] taxes [in that year] …

but for the advice of Xuanye’s senior advisors, who had persuaded him to spread the income sacrifice over three years.Footnote 12

How did a one-year remission of the land tax address the problem of rising population pressure on a finite quantity of land? A case could have been made that farmers were to be empowered with savings that they could invest in raising productivity, but the edict’s grim formula di bu jia zeng, chan bu jia yi 地不加增, 產不加益 (literally, “the land does not grow more extensive, nor does output grow larger”) suggests cognitive closure even to absolute expansion of output as a result of population growth, let alone the possibility of raising output per unit of land or labor. To jump to the conclusion that Xuanye and his advisors were really so closed-minded would be to ask too much of rhetoric: this was an edict that began by claiming that the pious aspirations that the newly acceded Xuanye had shared with his grandmother at the age of six had guided his conduct as emperor for the past half-century.Footnote 13 Enough that the text speak of his commitment, frugality, compassion, and past generosity in waiving taxes; the perceived public-policy challenge of demographic increase was but the backdrop to his magnanimous initiative. Detailed assessment of the pros and cons of possible policy departures was the stuff of everyday governance. For a jubilee, the grandeur of the gesture was what mattered.

The problem of mismatch between public-policy challenge and monarchical response recurs in the 1712 edict freezing the ding component of the tax base, albeit in a different way. This initiative, through which the court formalized the late-imperial state’s habit of extracting much less revenue from what was nominally a kind of poll tax than the actual population size would have justified, has been described as “one of the most unfortunate economic and political acts of the first century of Qing rule.”Footnote 14 The edict oddly asserts that “Although the numbers of adult males have increased, the acreage has absolutely not expanded” to justify the position that it would be improper for the state to levy the extra income that corresponded arithmetically to the extra population. As is well known, in promising to refrain from doing this, Xuanye was ostensibly trying to cajole the territorial bureaucracy into reporting the complete, up-to-date population data that were all he professed to want. The deficiencies of the population figures arriving from the provinces were the edict’s point of departure. The following passage is as revealing as it is ambiguous:

Wherever We have gone in Our inspection tours, We have [learned by] inquiry that a household may have five or six adult males (ding) of whom only one is paying taxes, or nine or even ten ding of whom only two or three are paying taxes. When We enquired as to what the surplus males are doing, all said “Being in receipt of Your Majesty’s extensive grace, they are absolutely free from labor service (chaiyao 差徭). All that they are doing is enjoying peacefulness and joy, [living lives of] ease and leisure.” This came out very clearly from Our enquiries.Footnote 15

Should this passage be read as an indication of the severity of the problem of the under-registration of able-bodied adult males, or as an expression of satisfaction that benevolence such as Xuanye intends is already being noted to his credit? It is arguable that, while both meanings are present, the second is the stronger. Ability to keep the majority of male household members free of burdensome obligations would be a hallmark of superior government. Which emperor would not want to be known for that?

It is not entirely clear that Xuanye intended to perpetuate the inequitable happiness that he had described. His final orders read as follows:

The named human ding (you ming rending 有名人丁) [entered] in the registers of taxes currently levied in Zhili and the provinces are to be adopted as a permanent fixed total. As to the human ding born from this time forward, increases in the tax [quotas] in respect of them are not to be imposed. All that is to be done is the preparation of a separate register to report the actual figures. Surely this would not merely be of benefit to the people; it would also be a glorious undertaking (shengshi 盛事).Footnote 16

The edict does not state explicitly that Xuanye intends a two-tier system in which those ding fortunate enough to have been “born from this time forward” would be exempt from the service levy, while the existing ding would remain liable. That this was a legitimate interpretation of the edict’s wording and a subsequent recommendation by the Nine Ministries Assembly is, however, confirmed by the fact that a Chinese remonstrance asking that such unfairness be redressed was soon to follow. Space permits only a brief account of how the ambiguity was settled and how interactions between Xuanye and ministers more knowledgeable than the remonstrant led to bureaucratic acquiescence in the subjugation of equity and rationality to the fabrication of an enhanced image of Xuanye as worker of glorious deeds in the “glorious age” (shengshi 盛世) inaugurated by his jubilee.

Xuanye responded encouragingly when the remonstrant, a vice-president of the Board of Rites, proposed a reform to make the new arrangements fair. If the tax quota corresponding to the ding numbers of 1711, the jubilee year, became immutable as now envisaged but the ding registers were updated quinquennially, equal division of the unchanging quota among an ever-growing number of ding would result in the burden per individual growing progressively smaller, to the equitable benefit of all.Footnote 17 What this remonstrant overlooked was that language assuming human ding was being used in a context in which the ding was increasingly a non-human unit of liability to pay tax in monetary form. From the second half of the Ming dynasty onwards, the labor service components of the realm’s agrarian taxes had increasingly been commuted to silver payments that were levied partly or wholly on arable land or simply amalgamated into the land tax. While the full potential of the aptly named “Single Whip Reform” reform would not be realized until Yinzhen’s reign and even later, the setbacks associated with China’s seventeenth-century crisis had not fundamentally undone partial tax-structure rationalizations that were consistent with long-term socioeconomic trends and administratively convenient at the county level where they had been introduced.Footnote 18

One effect of Xuanye’s intervention was to institutionalize the continued use of the term ding in its strict but largely antiquated sense even as the problematic implications of his orders spurred further moves for the dehumanized ding’s obligations to be absorbed into the land tax.Footnote 19 According to a late eighteenth-century compilation, the recommendation of the Nine Ministries Assembly in 1712 had been to adopt the ding totals stated in “the tax-collection ding registers for the fiftieth year of the Kangxi reign” as the permanent quota. New additions were to be called “the proliferating human ding of a glorious age” (shengshi zisheng rending 盛世滋生人丁), and tax was “never to be applied to [that is, levied on] them” (yong bu jia fu 永不加賦).Footnote 20 The formula yong bu jia fu was incorporated into year-end statistical summaries, which from 1713 until 1734 (the last whole year of Yinzhen’s reign) appear in the Veritable Records with the opening formula “This year the population expressed in human ding [rending hukou 人丁戶口] [numbered] …, and the proliferating human ding to whom tax is never to be applied [yong bu jia fu zisheng rending 永不加賦滋生人丁] [numbered] … .”Footnote 21 The senior officials of the Board of Revenue, who probably drafted the 1712 recommendation of the Nine Ministries Assembly, would have seen no harm in humoring Xuanye by letting this happen, because they must have known that it would have limited meaning on the ground. There was little question of applying a labor-service tax to extra human ding where the tax payable on a county’s ding total was already being levied partly via the land tax. Counties that faced problems of inequity would probably address them by further rationalizing the local tax system, and county magistrates were in any case notoriously disinclined to strive officiously to supply the public coffers with every candareen of silver to which those coffers were theoretically entitled (hence the persistent underreporting of human ding numbers). The idea that the state need not impose labor service duties on more men than it required had a pedigree traceable to the early Ming dynasty, and local society had its own ways of adapting and indeed exploiting government systems to its own advantage, as in the remarkable case of the consortium of thirteen local lineages in early eighteenth-century Fujian that purposefully acquired and parceled out 114 “official fiscal individuals” as part of a deal to secure a household registration.Footnote 22

All Xuanye accomplished through the freezing of the ding quotas was to legitimize the existing fiscal laxity and elevate it to a higher moral plane. It is no accident that in representing surplus ding as passive beneficiaries of imperial grace the 1712 edict paints out the agency of subjects who made their own arrangements to ensure that the state’s requirements were met and did not infringe further than necessary on the freedom or resources of a descent group’s adult males.Footnote 23 The point was to fabricate an image of the happiness wrought by the kindly governance that refrained from burdening more people than it needed to. Only thus could perpetuation of existing inequities through the freezing of the ding quotas be plausibly included as part and parcel of the “glorious undertaking” that would give the central government accurate ding figures. In taking the hint and creating a category called “the proliferating human ding of a glorious age,” and in setting the administrative beginning of that glorious age in the fiftieth year of the Kangxi reign, the Nine Ministries Assembly was taking the fabrication a step further. Harmless as the flattery may have seemed to those who understood that “adult males” had increasingly become token units of tax discourse, it should not escape our notice that monarch and ministers were responding with a pro-natalist tax policy to the secular challenge of a growing population on an ultimately finite quantity of arable land. With the proliferation of human progeny explicitly associated with glorious rule, it would have been a radical political economist who noticed that tax disincentives to procreation might be more apposite—and a bolder one yet who said so.

There is a marked contrast between the above Kangxi-era edicts in which the well-intentioned monarchical mind is shown concerning itself with public policy and popular well-being and the Qianlong-era edicts that are ostensibly inspired by a wish to emulate that magnanimous mind’s heritage. Even Hongli’s first two universal tax remission edicts fail to resurrect the solicitous presence of a ruler reasoning, however badly, about his subjects’ food security and quality of life. Assertions of the value of fiscal restraint feature in some of the Qianlong-era edicts, but these edicts convey no sense of an individual mind trying to engage with practical issues of political economy. Hongli himself is relatively absent, whether as person or persona, from these presumably ghostwritten texts; where we meet him, he is principally son (usually of his mother) or grandson (of his grandfather), not robust ruler in the Xuanye mode. He is imitative of Xuanye, whose lavish generosity he repeatedly equals or outdoes, and ostensibly also of his father, who appears only in the first edict of the series and to whose textual representation I shall return.

The edict of 5 July 1745 that announced Hongli’s original intention of a single one-year sacrifice of the whole realm’s land tax gives the reader to understand that the monarch is hard-working and frugal. Its rhetorical emphasis is on the fiscal order and restraint that flourish in his government, and on the legacy, inherited from father and grandfather, of munificence to taxpayers. Linking these two themes is the observation that in order to “uphold fullness and protect stability,” the first priority should be “sufficing the people,” a sentiment that the author—presumably a member of Qianlong’s close advisory body, the Grand Council—sought to reinforce by rehearsing the cliché that “There is only so much wealth in the world; if it is not concentrated above, it will be dispersed below.”Footnote 24 Not one word of elaboration follows. Which was the implicit vision: a society resourced for self-help or a moral ruler who eschews grasping behavior because he prefers his subjects’ benefit? The lack of elucidation suggests that the court’s attention was not on public policy. Nor was it on fiscal reality: it was with treasury reserves barely sufficient to meet all likely contingencies that the edict reiterated the truism that wealth that escapes government stockpiling can enrich society at large.Footnote 25

The edict devotes several lines to providing examples—one or two of them a little specious—of the sound financial management, especially restraint in government expenditure, that it credits with having created the capacity for Hongli to be generous. One notes, following Peter Perdue, the contrast between Hongli the stay-at-home executive and Xuanye the travelling inquirer.Footnote 26 What replaces the textual presence of the caring Xuanye is an invocation of his legacy and that of his son Yinzhen, Hongli’s father. “History does not come to the end of recording” the proclamations of tax remissions that had punctuated the grandfather’s sixty-one-year reign; “there was no day on which [the father had] not sent down” orders for reductions in tax burdens or leniency in collection. Hongli’s desire was, “in the spirit of continuing [their] intent and transmitting [their] undertakings, and at [this] season of redoubled splendor and protracted concord” (the advent of the tenth anniversary of his own accession), to confer “great bounty” on everybody in the land, equitably and without exception.Footnote 27

The rhetoric about emulating Hongli’s immediate ancestors was standard fare, but it was also paradoxical. Michael Chang’s discussion of the arguments for imperial hunts and tours advanced in edicts of the 1740s similarly shows a rhetoric of obedience to the royal forebears’ example being used to justify activities that might cause consternation among rationalist administrators. For Chang, defense of the hunts and tours was an “ethno-dynastic” matter. In “taking one’s ancestors as models” and making their mentality one’s own, one was recommitting oneself to the continuation of the dynastic enterprise. In episodically shunning sedentary ease for the rigors of the chase, one was living out fidelity to the martial, Manchu values transmitted by Xuanye from more distant ancestors.Footnote 28 The 1745 universal tax remission was certainly an affront to fiscal rationality. From a budgetary perspective the timing could hardly have been worse.Footnote 29 However, any connection with martial, Manchu values is unclear, and there was some incongruity in a claim to be honoring Xuanye, the founder of the dynasty’s eighteenth-century fortunes, by throwing prudence to the winds and celebrating a mere decade on the throne by announcing a universal tax remission amid complacent platitudes.

The 1766 edict announcing a rolling one-year remission of the tribute grain is in some ways the most interesting of the series. It unabashedly relates the early repetition of Xuanye’s universal tax remission by Hongli’s younger self, but it also shows Hongli at the age of fifty-four bringing his instinct for munificence back into sync, so to speak, with that of his illustrious forebear. Hongli is shown noticing that the time is ripe for him to celebrate his thirty-year anniversary with the same munificent gesture as had accompanied Xuanye’s accomplishment of thirty years of rule in 1692. Not only does his ghostwriter skillfully deploy a two-character allusion to the Analects to suggest a rationale for celebrating three decades as emperor; he also initiates a line of succession that bypasses Yinzhen. Here is the story as the edict tells it:

Now food occupies first place among the eight aspects of governance, and special reliance is placed upon abundance in the people’s [own] reserves. On respectful perusal of the Veritable Records of Our August Grandfather, [We found] that in the thirtieth year of his reign, he made a point of issuing a gracious edict [proclaiming] a round of comprehensive remissions of each [liable] province’s … tribute grain. The magnificent kindness fell [upon all] equally; the blessedness surpassed the norm. Gazing upwards, We call to mind that in the thirtieth year from his accession, Our August Grandfather, having climbed the regnal staircase in His childhood years, had not yet reached the age of forty. It was at the age of twenty-five [twenty-four by Western reckoning] that We ascended to the Great Treasure [the throne], and thirty years in the receipt of blessings have likewise passed [from that time] until now.Footnote 30

There follows a grandiloquent celebration of the present period of abundance and peaceful colonization following the recent imperial expansion—presumably the conquest of Xinjiang and Turkestan during 1755–59. While the first-person Hongli of the text is inspired to his act of grace by Heaven’s munificence, the last sentence before he gives his orders has him “striving to continue the Former Plan” (qian mo 前謨). The honorific elevation of the characters qian mo signals that it is Xuanye’s plan that is meant.

Why should the completion of thirty years of rule have been an anniversary meriting an act of grace? The phrase bi shi 必世 (literally, “certainly a generation”), used in a sentence on the gesture’s timeliness, would have been understood as a literary way of saying “thirty years” but also recognized as an allusion to the Analects. Confucius is supposed to have made the shocking statement that “If there were one who ruled as King, it would certainly be a generation before he was benevolent,” which may have been the voice of realism for Confucius’s own day. Premodern commentators varied in the extent to which they honored the actual words as opposed to forcing them into harmony with the sage’s presumed teachings.Footnote 31 An allusion to Confucius warning that benevolence could be expected only after three decades of kingly rule would have been singularly apposite in the wake not only of the slaughter of the Zunghars in 1757 but also of the harsh repression launched in the early 1750s against two internal threats to dynastic stability. That the allusion resonated in high Qing China, if only as conveying vaguely that benevolence could be expected after three decades of rule, is confirmed by a reference in the 1770 tax-remission edict to Hongli’s action of 1766 as having taken place at the right time for a “thirtieth-anniversary initiation of benevolence” (bishi xing ren 必世興仁).Footnote 32

Perhaps the 1766 gesture’s safety emboldened Hongli to diverge again from his grandfather’s example by announcing the next universal land-tax remission as soon as 1770, instead of awaiting his fiftieth anniversary in 1786. Forgoing the grain tribute from one, or at most two, provinces per year from 1766 until 1772 would have only minor impacts on the logistics of payment and provisioning for the metropolitan establishment or even the price level on Beijing’s grain market. A rolling remission of the land tax during 1770–72 was also rather safe because by 1770 the public exchequer was richer than it had ever been in the Qing dynasty. The Board of Revenue’s reserves had risen by an average of more than 4.5 million taels per year from 1760 to 1769, the total increase being from about 35.5 million to more than 76.22 million, or 114.7 percent.Footnote 33 The 1770 edict notes the rising surpluses, the remark serving as cue for a rehearsal of the principle that it is better that the world’s limited amount of wealth be left to “circulate spontaneously” (zi wei liutong 自爲流通) among the thatched hovels of the countryside than that it should accumulate excessively in the state’s treasuries. The eccentric wording of the conventional reference to the finite nature of the world’s stock of wealth (tiandi zhi ci shengcai zhi shu 天地止此生財之數, literally “Heaven and Earth [have] only so much wealth-creating quantity”) may suggest that “wealth” was here conceived as agrarian capital but may be merely careless. There is no attempt to explain how the retention of one year’s tax funds would economically empower taxpayers, of whom those who stood to keep the largest sums did not live in hovels.

The 1770 edict again recalls Hongli’s 1745 repetition of Xuanye’s universal tax remission, and it also resembles the 1766 edict in claiming that “Of recent years, the world has been well-ordered and at peace,” as perhaps we should expect of a court that was digesting the evidence that the last few years’ conflict with Myanmar had led to defeat. This was not the first edict in the series to sacrifice acknowledgement of hostilities to the image of tranquility.Footnote 34 This time, however, there is no suggestion that the placement of extraordinary acts of grace in Xuanye’s chronology of rule should provide a template for his grandson. The 1770 universal tax remission was grounded in a justification so impregnable, it seems, that whys and wherefores were superfluous. Not only had “storage of riches on behalf of the people” (wei min cang fu 爲民藏富) reached its apogee; this year would see Hongli’s sixtieth birthday, and the following year his mother’s eightieth (both by Chinese reckoning). Such an occasion called for spectacular munificence “in order to co-operate with Heaven’s heart and make known the dynastic rejoicings.”Footnote 35 The throne was clearly still a very powerful institution if such a coincidence could be elevated into a conjuncture of cosmic significance. Hongli’s mother’s eightieth birthday was indeed to be feted with the exceptional pomp and circumstance befitting a “[May the Royal Personage] Live Forever Celebration” in 1771, as had her sixtieth been twenty years before.Footnote 36 Hongli awaited his own eightieth before permitting himself an extravaganza of the same status, but linking his sixtieth to his mother’s eightieth in a gesture of sovereign benevolence was a masterstroke of image fabrication.

A precedent was now set for interrupting public income flows to mark personal life-course milestones in the imperial house. Hongli’s third universal land-tax remission was announced on 4 March 1777, two days after his mother’s death. The edict mentions two justifications for the remission: that on which he would have wished to act (his mother’s attainment of the age of ninety) and that on which he was now reduced to acting (her demise). It notes that the Board of Revenue’s reserves still exceed 70 million, but otherwise offers only sentimental elaboration on the reason for this burst of liberality to taxpayers. Hongli is revealed endeavoring to display his own sincerity and perpetuate his subjects’ regard for his late mother by giving them a last chance to enjoy her kindness.Footnote 37

At what point did commemorating monarchical anniversaries with tax remissions risk creating expectations among prospective beneficiaries? In November 1778, the mourning emperor faced the dilemma of a joint memorial from the two governors-general in whose jurisdictions lay the major cities of Jiangnan. They were urging him to meet the expectations of the region’s people by favoring them with an inspection tour in the spring of 1780, and they proposed to organize some spectacle for his delectation to celebrate his reaching seventy years of age. The first part of the request was acceptable—with his mother dead, Hongli no longer had to worry about how she would stand the journey’s rigors—but how could he agree to have his own anniversary celebrated now that death had dashed his hopes of another grand conjuncture in which he and his mother would reach the ages of seventy and ninety in consecutive years? In a lengthy edict, he noted that no one should try to please him by asking permission to organize celebratory activities or submitting poems of congratulation. However, he appreciated that:

It is normal and to be expected that the scholars and commoners of the whole realm will all be unable to help anticipating [the bestowal of] grace and favor on the occasion of Our attaining seventy years of age. How should We for Our part be willing to begrudge the grant of favor on the grounds that no celebration will be held?

Hongli announced two acts of favor, one to benefit the realm’s literati, and one the tribute-paying provinces’ landowners. There were to be special extra provincial examinations in 1779, a special extra metropolitan examination in 1780, and, in order to “store riches within the population,” another round of province-wide remissions of the grain tribute beginning in 1780.Footnote 38

The point of the 1790–92 universal land-tax remission was that, by Chinese reckoning, Hongli reached the age of eighty on the lunar New Year’s Day of 1790, when the remission was announced. The announcing edict was quite short and totally devoid of political-economic content.Footnote 39 This act of macro-munificence was soon followed by a round of province-wide remissions of the grain tribute—an act of grace that differed from all others discussed in this article in that it was represented as a direct response to extraterrestrial acts of Heaven. The edict that proclaimed this remission on 9 September 1794 was provoked by a warning from the Bureau of Astronomy that there would be an eclipse of the sun on New Year’s Day of the sixtieth year of Hongli’s reign (21 January 1795) and an eclipse of the moon on the fifteenth day (4 February). The edict’s tone almost betrays irritation with these intrusive portents from above, unbidden guests whose advent would mar the extraordinary anniversary of one who had served an entire sixty-year cycle with full diligence. Well might the wisdom of the ages admonish that “When there is an eclipse of the sun, [the ruler] should attend to [his] power [to transform others through morality] [xiu de 修德], and when there is an eclipse of the moon, he should attend to [his] penal [administration] [xiu xing 修刑]”; it was in fact incumbent on a ruler, preached the edict, to devote himself unsparingly to perfecting both in normal times. A competent ruler did not need eclipses to instill the requisite “mentality of reverence and caution.” We shall pass over the innocuous symbolic measures that the edict announced for adjusting Hongli’s penal administration; suffice it to note that the author affirmed that deeds to assure the people’s well-being were the best way of cultivating morally transformative power. The new round of tribute-grain remissions was the chosen deed for enhancing popular well-being, and it was to start in 1795.Footnote 40

The purpose of the 1796–98 universal tax remission was to mark Hongli’s abdication in favor of his thirty-five year-old son Yongyan 顒琰, who was to reign under the name Jiaqing until he died in 1820.Footnote 41 The annunciation edict was quite substantial and alluded to public-policy considerations to the extent of claiming that Hongli’s consistent, reign-long diligence had been governed by commitment to universal sufficiency of means through “storing riches within the population.” This claim is substantiated by a list of Hongli’s magnanimous acts: the four previous universal land-tax remissions, the three one-year remissions of the grain tribute, regional and local remissions and relief provision to the combined value of “not less than a hundred thousand times ten million taels” (that is, a million million taels), and recent total remissions of accumulated tax arrears to the value of “tens of millions” of taels.Footnote 42 There is hidden irony in the fact that Hongli’s abdication was ostensibly motivated by a pious undertaking not to compete with his grandfather over length of reign. The sainted grandfather’s jubilee-munificence edicts had not claimed more, for forgone tax income alone, than a cumulative total of 100 million taels and separate totals of 10 million taels on each of several unspecified occasions.Footnote 43

A second irony has to do with the ways in which the edict suggests Yongyan’s style of government will and will not resemble his father’s. What is to remain constant is the munificence towards humble rural folk. The point of inaugurating the new reign with a universal land-tax remission is to manifest the shared commitment of father and son to generous, gracious governance. However, a sudden respect for practicality may reflect Yongyan’s influence. Hongli had planned to release the good news in the new year (that is, on or after 9 February) after transferring the throne to his son, but realization that tax collection began in the second lunar month had made him change his mind. He reverted to the precedent established by his grandfather but ignored since 1766 of announcing the remission in the tenth moon of the previous year—on 18 November 1795.Footnote 44 The financial power that underpinned reckless munificence would not outlast the White Lotus war, but in this small way the 1795 edict presaged the ultimately ineffective reform efforts of the Jiaqing era.Footnote 45 The spell of Xuanye’s legacy was broken after his great grandson took over the reins of government. As Dai Yingcong has noted, “Universal tax remission, one of the hallmarks of the Qing golden age, never occurred again.”Footnote 46

That the doctrine that “dispersing” wealth “below” was preferable to “concentrating” it “above” was more a self-deceptive mantra than a policy position is suggested by its rehearsal in an edict of 1781 indicating that His Majesty was unimpressed by a proposal from his most senior councilor for savings in military expenditure. Although the edict notes that “money is fundamentally a circulating thing” (quanhuo ben liutong zhi wu 泉貨本流通之物), there is no explicit argument that the military spending was economically functional. Rather, the edict’s burden is that the magnificent fiscal wealth that has sustained three universal land-tax remissions and two tribute-grain remissions ought to preclude governmental parsimony—especially over the maintenance of that key strategic asset, the state’s military forces.Footnote 47 As long as wealth was viewed as capacity for munificence and military preparedness, its concentration was worthy of acclaim.

The Audience that Applauded

Assessing the actual economic impact of any of the high-Qing universal remissions of the land tax is beyond the present article’s scope. It is, however, worth reading a few of the adulatory memorials that greeted the announcement of Hongli’s ten-year anniversary universal tax remission against the grain to try to make sense of the beguiling imagery of remitted taxes enriching the domestic treasuries of thatched peasant cottages. The orchestrated provincial gratitude campaign evidenced by documents preserved in the Qing archives allows us to identify some groups of presumably appreciative spectators while leaving poverty-stricken beneficiaries somewhat to the imagination. The fact that the fulsome tributes to the young Hongli’s munificence were presented in routine memorials, not the palace memorials used for direct communication with the emperor, reflects the deceptive character of the entire laudatory enterprise—simultaneously both significant and hollow.

The memorial of November 1745 submitted in the name of Yan Sisheng 晏斯盛, the Hubei governor, bespeaks a concerted exercise in being seen distilling adulation into a documentary record for the central government’s files. There are just over five columns of names of shenshi 紳士 (persons qualified for office and state-validated scholars) and limin 里民 (villagers) into whose collective voice is put grandiloquent praise for the emperor and for the happiness and prosperity that reign under his governance. The memorial represents the expressions of gratitude as having been submitted to the county magistrates, who channeled them upwards to the prefects, after whom they passed through the (acting) provincial administration commissioner in conjunction with the surveillance commissioner and the team of circuit intendants with whom they ran the province. At every level adulatory rhetoric is added, including the final level, that of Yan Sisheng. The names of all the individual officials are provided, from the prefectural level up.Footnote 48

Memorials of this type vary in the extent to which they let the representatives of public opinion speak in what purports to be their own voice. The Sichuan and Guangxi submissions hint at an outpouring of spontaneous praise. The Sichuan memorial has almost five and a half columns of names of shenshi and qimin 耆民 (elders); that for Guangxi presents separate lists for shenshi and minren 民人 (commoners) but includes only four names in each—a sufficiently coherent group to have agreed on a text to be “submitted in [our] joint names.” This seems unlikely to have been the case for the Sichuan eulogists, by implication men of every corner of the province. The Sichuan eulogy as delivered may have been composed in Chengdu, since only the two counties seated in that provincial capital are named. While the addition of laudatory words from successive levels of the provincial hierarchy was a common feature of the genre, Saileng’e, the Jiangxi governor, monopolized most of the space in the Jiangxi memorial for his own eloquence, relegating to the end all mention of the passage upward to him of expressions of thanks from the gentry and commoners “of the entire province.”Footnote 49

In some places the eulogists are at pains to note that the benefit of the remission will be felt by poor and simple folk as well as the elite. Saileng’e offered a parallel-prose antithesis whose first clause situated the rejoicing peasantry within the local color of Jiangxi’s lacustrine landscape, while the second evoked the happy songs of swidden farmers. The Sichuan vox populi noted that tenants and the poor were “equally” to share in the rich bounty, of which, in fact, there was no guarantee. Hongli had rejected proposals under which landlords would have been required to pass on a predetermined percentage of the benefit in rent reductions. The acting Guangxi governor, Tuoyong 託庸, was more accurate in noting that the territorial bureaucracy was to “exhort [landlords] to reduce their rents appropriately [in the remission year] in order to treat tenants equally [jun dianhu 均佃戶].” Exhortation was an appeal to the conscience, and it was what Hongli had ordered in this case.Footnote 50 The reference in the Sichuan eulogy to the “equal” benefit envisaged for tenants may express the sanctimony of proprietors showing that they knew what was—ideally—expected of them.

Some of the eulogies flatter the emperor by imitating the vague ideological expression found in the remission edict. As noted above, Saileng’e showed eloquent recognition of the kinship of this ideology with the adage that riches should be stored within the population:

Rich reserves are to be stored under poverty-stricken eaves; down to the very coasts, rejoicing hearts will be in great accord. The levying of tax is to be slackened during years of plenty; the pure breeze of the [Jiangxi] camphor trees will spread far and wide.Footnote 51

The spokesmen for the Sichuan taxpayers also understood how the remission was supposed to be good for them:

Six hundred and thirty thousand [taels] of tax levied on [our] fiscal individuals are all to be remitted, and [our] 140 and more commanderies [prefectures] and counties will not be engaged in tax delivery. The stockpiles [accumulated] in the villages will grow still more, and the delight of scholars and the common throng will be redoubled.Footnote 52

Had the authors been relishing plans to use their share of the remission bonanza as investment capital, it would have been impolitic to say so. Instead, their terminological choices incline the reader to imagine the prudential enhancement of peasant grain reserves, thus evoking a reassuring picture of stable rural life. The 630,000 units of tax were definitely taels of silver. Sichuan’s land-tax quota in 1753 was just over 659,000 taels, and it is plausible that it was somewhat less a few years earlier in 1745.Footnote 53 The phrase qianliang 錢糧, literally “money and grain,” was routinely used of the land tax in late-imperial China, even after payment in silver had become the norm. In substituting the term dingliang 丁糧, literally “grain levied on fiscal individuals,” the authors preconditioned the reader to envisage the weiji 委積, “stockpiles,” as stockpiles of grain—the grain that would not need to be marketed if farmers had no tax to pay. The rhetoric is not only conservative but also anachronistic. There was money to be made in Sichuan from sale of the grain that would eventually feed urban markets in Jiangnan. The rational economic actor would have hesitated to stockpile perishable grain unless for shrewdly assessed speculative purposes.

Even once the stockpiles were understood to be of silver, what beyond rhetorical convention debarred eulogistic recognition of their value if not stored? Yan Sisheng was somewhat realistic, albeit wisely reticent. Never before had there been such a “[case of] three years’ quota[-governed] levies not entering the public gates [gongmen 公門] and [of] baskets round and square containing coin and silver in the tens of million being retained in private houses [sishi 私室].”Footnote 54 With mercantile Hankou just across the river from his office in Wuchang, Yan was probably not short of ideas for more dynamic uses to which “retained” money could be put. The purchase of more land would have been an alternative investment option, and not one that conduced to the long-term benefit of those smallholders in a sufficiently weak position to consider selling. If Yan’s use of the value-laden terms gong 公 (public) and si 私 (private, selfish) hints at irony, the disguise had to be heavy. It was safest to keep one’s rhetoric within the confines of a literal understanding that riches were best “stored” within the population.

Proprietors of agricultural land, from poor peasants to rich estate-owners, were the one category of certain beneficiaries of the universal tax remission, assuming honest, effective administration. Elite in comparison with landless laborers, vagabonds, and full tenants, they were, qua landowners, the best kind of commoners in what Pierre-Étienne Will calls “Confucian sociology.”Footnote 55 Those with most to gain from the remission were those with the largest tax bills, that is, in principle, those best endowed with landed wealth, including landowning members of the civil service, the most significant elite status group in late-imperial Chinese society. While shenshi were indeed well represented among those listed as expressing thanks, there is a predictable reticence regarding how the universal tax remission would benefit the privileged and wealthy. In the provincial eulogies, voices joined in chorus to acclaim collective benefit to the entire body of taxpayers and/or to humble cottagers, including tenants.

In 1745, Hongli probably had reason to consolidate his efforts to build an image of himself in the eyes of the broad Chinese elite as more accommodating of their interests and values than his father had been. The extent to which his policies and actions actually differed from Yinzhen’s is controversial and has probably been overstated in some scholarship.Footnote 56 It is, however, plausible that the more continuity there was between Yinzhen’s ways and his own, the more incentive Hongli had to reclaim and excel his grandfather’s legacy. Hongli’s 1745 tax extravaganza marked not a jubilee but a first decade. The foreshortening of celebratory qualifying-time bespeaks eagerness to impress the Chinese elite as the supreme paragon of that convenient hallmark of Confucian monarchy, commitment to light taxation and generosity to taxpayers. However, with the Chinese elite significantly absorbed into the Qing ruling structure, impressing this broad socioeconomic group with his will and power to be the supreme patron of Chinese landowners was probably not essential for Hongli. To make sense of the risk-taking in terms of Hongli’s likely preoccupations, we must look closer to Beijing.

The 1745 Universal Tax Remission and the Retreat from Heredity

I open the following discussion (after some prefatory remarks) with a mischievous comparison: between Louis XIV’s initiation of the Franco-Dutch War in 1672 and Hongli’s initiation of the 1745 universal tax remission. My point of departure is not the contrast between the forms of power—“hard” in Louis’s case, “soft” in Hongli’s—that each monarch deployed, but the elementary fact that each ruler was aged thirty-three and had held the reins of power for about a decade at the time of his initiative. We have watched patiently as Hongli’s ghostwriter lengthily fabricated a parallel between Hongli and his grandfather as veterans of thirty years of rule. It is time to turn the tables with a parallel, not of Hongli’s choosing, that may help us to new insights. The themes of fiscal glory, martial ignominy, intergenerational repulsion and self-actualization will feature in my account of why in 1745 Hongli decided that the realm could spend a year without its staple source of public revenue.

The term “self-actualization” requires definition, as it is neither pejorative nor a synonym for “self-aggrandizement” or “selfishness.” Topping the pyramid of Abraham Maslow’s well-known “hierarchy” of human needs, the self-actualization need is that stirring of impulses to become fully what we have it in ourselves to be—whether scholar, sage, violinist, “ideal mother,” or tennis champion. Maslow’s later, idealistic elaboration of a concept that he adumbrated simply in 1943 need not detain us here.Footnote 57 It does no excessive violence to his original formulation to apply the term “self-actualization” to the project of young monarchs endeavoring to turn themselves into kings / sons of Heaven worthy of the name.

To compare high-Qing China’s fiscal arrangements with those of Bourbon France would inevitably be unfavorable to the latter. Sino-Manchu, but not Bourbon, rulers had at their disposal a stable, rational, centralized, essentially top–down fiscal system whose broadly predictable performance was a precondition for the planning of a rotating one-year remission of the staple fiscal imposition on the population. Ancien régime France, by contrast, was burdened with a poorly coordinated public revenue system in which the downward diffusion to private financiers and tax farmers of the power to exert influence, along with the circumscribed penetration into the bastions of noble and ecclesiastical privilege of the state’s power to exact resources, precluded the orderly financial governance required for predictability. Mounting military expenditures in the first half of the eighteenth century might inspire the abler directors of state finances to try experiments some of which went in the direction of “modernity,” but mastery of the whole system was beyond their reach.Footnote 58 It was only in 1749, when the three-year implementation of Hongli’s first universal tax remission was already complete, that the need to grapple with the deficits induced by French engagement in the War of Austrian Succession provoked a French controller-general of finances to attempt a rational, universal, bureaucratically administered, equitably apportioned ad hoc levy on income.Footnote 59 The notion that the Sino-Manchu Board of Revenue could efficiently and effectively mastermind the sacrifice of the entire staple revenue for a designated year might well have left his master, Louis XV, speechless.

Fortunately, the pointing of cross-culturally judgmental fingers plays no part in the comparison that follows. The purpose of the comparison is rather to jolt the discussion out of the Sinological comfort zone of text analysis and into the flesh-and-blood world of real, albeit long-dead, monarchs exercising power. Jeroen Duindam has argued that “the normative worlds of dynastic power need to be put into a comparative perspective before we can effectively evaluate the structures and practices of power.”Footnote 60 In the more modest inquiry undertaken below, the similarities and differences between the positions within structures of two relatively young men poised by their supremely privileged life circumstances for adventures of self-actualization prompt reconsideration of the meaning of their exploits, Hongli’s in particular.

Paul Sonnino once wrote that Louis XIV “went off to war at the end of April 1672 like a hero to his victory.”Footnote 61 Resolved, as Louis put it at the time, to “begin my campaign with something of great brilliance,” he launched his effort to make a meal of the Dutch Republic with a shock assault on “four strongholds on the Rhine,” after whose rapid fall he had his army swim across that river—a feat that became the stuff of court poems and paintings.Footnote 62 After that, however, Dutch resistance and the reaction of the other European powers, most of whom united against him, sobered the elation. The war ended with the lackluster peace of Nijmegen in 1678–79. Not only had Louis’s martial adventures imposed sufficiently on taxpayers to occasion two major uprisings, they also generated international misgivings the bill for which would be presented ten years later in the form of concerted resistance to renewed French aggression. The result would be protracted hostilities that exacerbated a severe crisis in France’s agrarian economy.Footnote 63 Louis eventually came to recognize his attack on the Dutch Republic as an indiscretion of his early years, when he had been, as Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie puts it, “obsessed with his own standing in the world.”Footnote 64

Louis’s standing in the inner counsels of the Bourbon monarchy had been long in the attaining. He had acceded to the throne in 1643 at the age of four, and his mother’s regency had ended in 1651, when he was deemed to have come of age. He had been crowned in 1654 but had had to wait until the beginning of the 1660s to exercise those prerogatives of kingly manhood, marriage and self-actualization at the helm of government. Even his ceremonial entrance into Paris in August 1660 had been overshadowed by allegorical representations of larger-than-life contributions on the part of his mother and the chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin. Mazarin, who had risen to power while Louis XIII was dying, had given the adolescent king some training but had not handed over the reins of government before he died in 1661.Footnote 65 While taking full charge within forty-eight hours of Mazarin’s death may have been more a fulfilment of his mentor’s tutelage than a reaction against it, Louis’s actions were drastic and decisive. He declared his intention of dispensing with the help of a chief minister and purged the high and mighty of nobility and church from his innermost council, replacing them with ministers whose aptitudes had been nurtured in the very different milieu of ex-bourgeois families. The changes that Louis implemented featured centralization of decision-making power in the person of the king, his small inner circle, and his specialist committees. By 1672, Louis was building on his precocious success, that is, the reputational, financial, military, and naval power already nurtured for ten years through the energetic initiative of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, once manager of Mazarin’s wealth, whom Louis had elevated during the years 1661–65.Footnote 66 It is no great wonder if Louis overdid self-assertion in foreign policy and thereby opened the pathway to later distress.

Hongli, in his first decade of rule, was like Louis XIV seven decades earlier in that both young rulers played roles in institutional innovation that tended to promote centralization of power in the ruler and the conciliar structure that directly supported him. Both had their problems with the power of the senior generation, but the timing and therefore the nature of the struggle was different in each case. For Louis, who can have had only the vaguest memories of his father, it was his mentor’s death that unleashed him to enact, at the very beginning of his personal rule, what Le Roy Ladurie calls “a minor administrative ‘revolution.’”Footnote 67 For Hongli, it was the father’s death that cleared the way for a comparably significant institutional change: the creation of the monarchical cabinet that began as a regency council and was made permanent in early 1738 under a name usually rendered in English as “Grand Council.” This change was likewise initiated, in Hongli’s name, from the very outset of his reign.Footnote 68 Hongli had turned twenty-four (by Western reckoning) on 25 September 1735, thirteen days before his father Yinzhen died at the age of fifty-six with noteworthy institutional innovation and enhancement of monarchical power to his credit.Footnote 69 The regency council was necessitated not by monarchical infancy but because the Chinese cultural obligation of mourning a father into a third year was taken to be incompatible with the vigorous, assertive exercise of government responsibility. Hongli was not debarred from issuing monarchical decisions, but there was a tension between the willfulness with which he sometimes did so and the convention that he needed the support and guidance of the Princes and Grand Ministers in Overall Charge of Affairs whom his father had chosen to assist him.

The two senior statesmen who led Hongli’s regency council, Ortai (1680–1745) and Zhang Tingyu 張廷玉 (1672–1755), were like Mazarin both in being the likely architects of their royal master’s “administrative revolution” and in remaining in position after the regency ended—or rather, in equivalent position as leaders of the new Grand Council.Footnote 70 They were, however, unlike Mazarin in their failure to die until the ambitious young ruler had reached the age of thirty-three in Ortai’s case, forty-three in Zhang’s. They were both there, with all the weight of the senior generation’s prowess in developing institutions of centralized monarchy, throughout Hongli’s first decade on the throne and almost throughout the first eight years of his personal rule. To them belonged the credit for guiding the transformation, during the years 1735–37, of a small regency council with 50 percent representation of the royal family into the prototype of the well-staffed bureaucratic council of state that was to underpin monarchical power for the remainder of the high-Qing period. Qianlong’s modest protestations, when he emerged from mourning in early 1738, that he could not dispense with the council’s assistance legitimated his perpetuating a promising instrument for the enhancement of centralized rule.Footnote 71 The self-abnegation was deceptive.

If, as Mark Elliott suspects, by the fourteenth year of his reign Hongli was experiencing a “desire simply to be rid of [Zhang Tingyu] and of the last reminders of his father’s rule,” we may reasonably suppose that the reason lay partly in an inadmissible craving for liberation from the lingering authority of a senior generation to whom much was owed, and partly in those aspects of the father’s rule of which the son did not much care to be reminded.Footnote 72 To a young adult heir, the father who dies in late middle age cuts a very different figure from the sexagenarian grandfather who died when one was eleven. Hongli the grandson would have known a military veteran who had been glorious in the saddle, accompanying his army on successful campaigns before Hongli was born.Footnote 73 In the late summer of 1731, by contrast, when Hongli was nearly twenty, his father had, at a safe distance, suffered the humiliation of a major defeat in a rash offensive against the Zunghars. This “military disaster,” as Perdue calls it, exposes for the historian a number of Yongzheng’s personal weaknesses, as reflected in a secret missive in which he bewailed his “sins” and “crimes” and declared himself “anxious and afraid.”Footnote 74 Whether or not Hongli was privy to his father’s state of mind, he was surely old enough to notice that, whatever appreciation Yinzhen might show for martial, Manchu traits in interviewees for military or bureaucratic office, martial, Manchu values were not being spectacularly transmitted through his own person.Footnote 75

Yinzhen’s commitment to continuing the Kangxi heritage had been exiguous in other areas as well. In 1750, Hongli was to be frank: his father had reigned for thirteen years without implementing an inspection tour, with unfortunate consequences for the skills of the Bannermen who would have accompanied him.Footnote 76 Yinzhen’s generosity to taxpayers also offered nothing conspicuous to set beside Xuanye’s jubilee remission of the whole realm’s land tax. The ghostwriter of the 1745 universal tax remission edict was reduced to the obviously hyperbolic assurance that “there was no day on which [Yinzhen] did not send down an order for reduction of tax or leniency in collection,” followed by the lackluster example of Gansu, total remissions of whose regular tax quota—one of the lowest in the realm—had taken place “during ten years and more.” Remitting the land taxes of arid, poor, drought-prone Gansu would always look commendably benevolent. However, those who knew how the realm’s finances worked would have understood that the Gansu land tax was far from being the sacrifice that the tax of those provinces that subsidized the outstandingly costly Gansu military would have been.Footnote 77

There is nothing on the surface of the 1745 edict to suggest any intent less creditable than justifying an act of extraordinary generosity to taxpayers as a continuation of the virtuous heritage to which Hongli had succeeded. The edict allures readers with the beguiling vision of “those in and those outside the center” uniting in appreciation of one province’s felicity in enjoying total remission of all its land tax for more than ten of the thirteen years for which Yinzhen had ruled.Footnote 78 At the deeper level to which we are beckoned by the fact that the beneficiary province was Gansu, however, we discern a monarch for whom, in reality, the “nightmare” of heredity lay in his similarity to his father, seeking to reconstitute himself as heir rather to his grandfather and his grandfather’s glory.Footnote 79 As the edict was a formal, probably ghostwritten, public document, a psychological interpretation should not be pressed. Nonetheless, inadmissible feelings underlying Hongli’s intergenerational legacy-leapfrogging would help explain its long-term dispensability. Twenty-five years later, with his father’s ghost shrunken, Hongli could switch his self-representational investment into being the filial son of the mother who was rising eighty.

Some fiscal statistics will help us to identify an irony that is implicit in the 1745 edict and thereby re-state the puzzle of the 1745 universal tax remission as a reclamation of Xuanye’s heritage. Not only had Xuanye awaited his own jubilee before awarding China’s landowners a one-year respite from the land tax, he had also imposed the sacrifice on the public exchequer at a time when the Board of Revenue treasury was quite well stocked, with about 45.88 million taels in 1710. This level was not far below the 47.18 million recorded for 1708 or the 47.37 million recorded for 1719. It exceeded the average known holdings both for the period 1691–1710 inclusive (almost 40.46 million taels) and for the last three decades of the reign (1691–1721: about 40.71 million). In the last remission year (1713), the treasury still held 43.09 million taels; between 1713 and 1719, known holdings did not dip below 40.73 million.Footnote 80 In 1710, the central government incurred a major income sacrifice with justified assurance that, when spread over three years, the cost could be absorbed.

In 1744, by contrast, the Board of Revenue’s treasury held only 31.9 million taels, and in 1745 only 33.17 million (possibly a year-end figure unavailable in July, when Hongli declared the universal tax remission). Average holdings for the years 1734–1745 inclusive were only 32.64 million taels; for the whole eighteen-year trough from 1734 to 1751, they were only 32.085 million. Under the combined impact of the universal tax remission and warfare on the Western frontiers, reserves fell to 27.46 million taels in 1748, the last remission year. In 1749 they were still only 28.07 million—somewhat less than the whole realm’s nominal annual monetary income from the land tax (28.2 million had been the target in 1745).Footnote 81 True, the state had other sources of income that contributed to meeting annual expenditures variously estimated as 42.2 million or 56–66 million taels.Footnote 82 Nonetheless, Hongli was warned in 1741 and 1745 by highly placed officials that the realm’s finances were on a knife edge between sufficiency and deficit. Public finances survived the challenges of 1746–1749, but not without inspired planning, demonstrable strain, and significant contributions (or at least pledges) from the private sector.Footnote 83

What had happened to reduce the 40-million-tael average holdings of 1691–1721 to the 32-million-tael ones of 1734–1745? A startling build-up of reserves in the middle years of Yinzhen’s reign had lifted the holdings of the Board of Revenue treasury to a peak of 62.18 million taels in 1730, after which they declined progressively until the 32.5 million-tael holdings of 1734 inaugurated eighteen years of relative fiscal stringency. The steepest drop in Board reserves (by 11.8 million taels—nearly 19 percent) took place in 1731, the year of Yinzhen’s disastrous military adventure. The remaining annual decreases until 1734 were by about 11.9 percent, 14.6 percent, and 14.3 percent. There may be exaggeration in the flattering contrast drawn by Hongli’s Grand Council in early 1757 between the reported cost to date of the successful 1756 campaign against the Zunghars (less than 18 million taels) and the 54.39 million taels that, they claimed, Yinzhen’s campaign had cost. Nonetheless, sample expenditure figures derived from archival documents confirm that the latter war was indeed costly.Footnote 84

The major irony buried in the 1745 edict is that what created the circumstances in which Hongli’s first complete remission of the land tax became a heroic celebration less of power than of daring was his father’s costly blot on the military prestige of the Qing dynastic house. Yinzhen, the careful conservator and rationalizer of the state’s resources, had ruled for thirteen years without any truly spectacular act of generosity to taxpayers, blundered his remote-controlling way into a resounding military defeat, and died leaving a central-government treasury that was not significantly richer than it had been in the penultimate year of his father’s reign (holdings of 34.53 million in 1735 compared with 32.62 million in 1721—the 1722 figure is missing). Hongli, with his image as military victor yet to be established, trumped not only his father but also his grandfather in celebrating a decade on the throne with a universal tax remission. Would he thereby inaugurate the re-establishment of his grandfather’s glory, or would his foolhardiness result in a retreading of his father’s path to ignominy? It was an extraordinary gamble, one that a resentful rejection of his father’s futile money-grubbing heritage seems insufficient to explain completely.

Whom was Hongli’s self-assertion intended to impress? It is worth reading an edict of 5 April 1742 in the context of its own time as well as recognizing it as an early manifestation of that antipathy to bureaucratic sluggishness that the late Philip Kuhn identified as a likely impetus to a witch-hunt that Hongli prosecuted in 1768 against persons suspected of stealing souls for purposes of sorcery.Footnote 85 In 1742, Hongli complained about the failure of his high officials in the Nine Ministries Assembly to engage in “deep planning and far-reaching thought” or to propound “fundamental strategies for the dynasty’s sake.” Taking advantage of an incipient drought to call for self-critical reflection by “ruler and ministers,” Hongli launched a critique of the routinized bureaucratic life that he imputed to the very men who should have been visionaries of projects for long-term amelioration of the realm’s affairs. Instead, they were “going early to their offices to handle paperwork, [only to] go home, shut the door, not see a single guest, and take that to be placid holding to their [proper] portion.” Hongli accused the Nine Ministries assemblymen of doing no more than suggesting changes to single rules and single clauses of the law in their addresses to him. Could such proposals “constitute great plans for durable peace and long-lasting good order?” he asked rhetorically. In noting that the assemblymen were generally older and more experienced than he, Hongli refrained from making noises about valuing their wisdom. Instead, he gave them orders.Footnote 86

“Great plans” were a specialty of Hongli’s. As early as March 1738, in his second month out of mourning, Hongli had overridden some authoritative advice he had received about a month before he doffed his mourning garb. He had given enabling orders for a quixotic scheme devised by an investigating censor to try to double reserves in the antifamine granaries. Hongli’s imperious call for “great plans” in the 1742 edict came against a background of growing evidence that the experiment was running aground.Footnote 87 It is understandable that he turned to his senior advisors for a fresh supply of grand ideas. But to whom exactly were his strictures addressed? Given that the Nine Ministries Assembly was an outer-court, civil-service body inherited from the Ming dynasty, and that the Grand Council that furnished Hongli with his ghostwriters was an inner-court tool of Manchu power, it comes naturally to read the 1742 edict as a pep talk to the heads of the bureaucracy. According to Beatrice Bartlett, however, from the days of the Regency Council onward, the grand councilors had led the Nine Ministries Assembly as members of the latter body. There was certainly an overlap of personnel, as is illustrated by the list of signatories to a joint recommendation by the grand secretaries and Nine Ministries Assembly in 1743. Of the six grand councilors participating, Ortai and Zhang Tingyu were listed as grand secretaries, three other dignitaries—two of them Manchus—as Board presidents, and the last primarily as a court expositor of canonical works.Footnote 88 Inner-court membership exempted no one from Hongli’s expectations of greater liveliness in outer-court deliberation.

What probably irked Hongli was the inertia that bureaucratic procedural and professional expertise risked generating, and its propensity to stifle monarchical self-actualization. The centrality of respect for seniority and wise counsel in Confucian political culture legitimized such inertia and probably did little to endear to the young Manchu ruler the old men still available to guide him as he grew in self-confidence. It is not that, by July 1745, he still needed to stage a head-on challenge to the influence that Zhang Tingyu and Ortai had wielded as the heads of patronage networks. Ortai was dead and had in any case been sternly rebuked and threatened by his master two years earlier. Zhang was in his early seventies, had already tasted punishment, and would soon seek release from duties.Footnote 89 It is rather that Hongli was taking it upon himself to supply the dynamism that he had found woefully lacking among the heads of the bureaucracy. It makes perfect sense that in 1745 Hongli challenged that citadel of cud-chewing paperwork, the Board of Revenue, with a monstrous affront to the predictability that enabled its operatives to pen-push comfortably and to the prudence that its leaders urged on him as if they knew better than he did. The entire metropolitan establishment could take note of his first universal tax remission as an early exercise of what Norman Kutcher has called “arbitrary power”—the kind of power that would subsequently underlie the monarchical “political campaign” as a tool of sovereign self-assertion.Footnote 90

The following interpretation of the 1745 universal tax remission appears consistent with the evidence. In showing the leaders of the metropolitan establishment who was master, Hongli invented a dynastic milestone and celebrated it with an action symbolizing that he had emerged from the shadows surrounding his father’s rule and would henceforth pursue glory worthy of his grandfather. Hongli’s once-off gesture of liberality to taxpayers was the antithesis of the on-going accumulation of silver surpluses that had marked the early and middle periods of his father’s reign. To those officials who remembered the link between the collapse of those surpluses and Yinzhen’s military errors, Hongli offered not an assurance of prudence but a promise of splendor. That, in 1745, the promised splendor was pacific and not martial suggests effective deployment of cultural politics in the context of the “renewal and elaboration of Chinese-Manchu tensions in the highest governing circles” that had resulted from Ortai’s and Zhang Tingyu’s preeminence.Footnote 91 The projection of an image of a monarch in the Kangxi mode—resolute, intrepid, and ultra-Confucian when it suited him—offered Chinese dignitaries reassurance that the Manchu ruler was qualified for celestial sonship while putting both sides on notice that their sovereign claimed the role of leader.