Introduction

In her thought-provoking book on the long history of milk(Reference Valenze1) and how this has been intertwined with social and economic developments, Deborah Valenze concludes that ‘Even after all the hard science of the 20 th century, milk remains more magical than the sum of its nutrients’. This was indeed prescient given what we now know about the dairy matrix and its influence on nutrient absorption and other factors.(Reference Weaver and Givens2) It is generally agreed that milk and dairy foods including cheese and yoghurt, are nutrient-dense foods that are key contributors to a range of crucial nutrients in the diet many of which are challenging to obtain in adequate amounts from dairy exclusion diets.(Reference Givens3)

There are concerns by some, that milk production and related processing have important detrimental effects on the environment although there are also concerns that the environmental impacts do not adequately reflect nutrient composition(Reference McAuliffe, Takahashi and Beal4) or health functionality.(Reference Leroy, Abraini and Beal5) Yet at the same time, there is increasing evidence that dietary patterns which contain higher proportions of dairy foods are associated with reduced risk of key chronic diseases.(Reference Akyil, Winkler and Meyer6) The mechanisms involved in risk reductions are many and complex and some are not fully elucidated but have resulted in milk and dairy products being labelled as functional foods. Functional foods have been defined as any food which contains biologically active compounds that provide physiological functions, regardless of their normal nutritional value as a healthy food.(Reference Howlett7) Certainly most, if not all these functionalities, would not be explained by classical nutrient composition.

Whilst diet and exercise are key risk modifying factors for a range of chronic non-communicable diseases, it is important to recognise that the risk of many such conditions varies according to life stage from foetus to old age. The aim of this review is to highlight some key health and development functionalities of milk, dairy foods and their components with their relevance at key life stages.

Milk and dairy and pregnancy outcomes

Effects on birth anthropometrics

Whilst the importance of milk during pregnancy as a source of iodine to reduce the risk of inadequate neural development(Reference Bath8) and vitamin B12 to reduce the risk of neural tube defects(Reference Ray, Wyatt and Thompson9) (due to its interaction with folate metabolism) is well known, there are further concerns about low vitamin B12 status during pregnancy being linked to detrimental foetal programming, low birth weight, preterm birth and a possible future risk of cancer.(Reference Hart, Hill and Gonzalez10) There is however less information on the association of milk and dairy foods and broader pregnancy outcomes. A systematic review of six cohort studies indicated a positive association of maternal milk intake during pregnancy and both infant birth weight and length.(Reference Achón, Úbeda and García-González11) However, the types of studies varied considerably and with few studies the authors confirmed that conclusions were not possible for associations with preterm deliveries, spontaneous abortion and lactation.

A more recent systematic review followed by a dose-response meta-analysis of 18 studies(Reference Huang, Wu and Xu12) showed general non-linear effects of maternal dairy intake and birth anthropometrics which included a preventative effect of small for gestation age at a maximum of 7.2 servings per day (RR, 0.69, 95 % CI: 0.56–0.85) but an increased risk for large for gestational age at 7.2 servings per day (RR, 1.30, 95 %CI: 1.15–1.46). Overall, the maximum mean increase in birthweight was predicted to be 63.4 g at 5.0 servings per day. The study concluded that the results were indicative of a growth promoting effect of milk, likely due to the stimulation of IGF-1 by milk proteins and potentially mTORC1 pathway stimulation which is anabolic growth stimulating. It was also found in the data from two studies that low maternal consumption of organic dairy products was associated with an increased risk of hypospadias in males, a finding which the authors felt should be taken seriously and investigated further despite the low number of studies involved. The authors also recommended that further studies are needed to assess the impact of individual dairy foods on all the outcomes assessed.

Effects of bovine milk exosomes

Exosomes are membrane-bound extracellular vesicles typically 30–50 nm in diameter that enable cell to cell transfer of regulatory molecules including miRNA. The latter are importance since they can regulate greater than 60% of human genes.(Reference Friedman, Farh and Burge13) Also, exosomes and their contained molecules are not entirely of endogenous synthesis as they can be absorbed from the diet including from milk. Interest in the potential health applications linked to exosomes is rapidly increasing with milk exosomes showing high human compatibility, no systemic toxicity and low adverse effects on inflammatory response and the immune system.(Reference Adriano, Cotto and Chauhan14) In the context of impacts on pregnancy outcomes associated with milk consumption, a study with mice has shown that bovine milk exosomes and their contained miRNA are bioavailable and accumulate in the placenta and embryos. The study also showed improved placenta development and embryo survival.(Reference Sadri, Shu and Kachman15) As the authors confirm, causal mechanisms for such effects need further research as will any translation to humans. It is though notable that nucleotide sequences are identical in human, murine and bovine miRNA and miRNA in bovine milk exosomes have been shown to alter gene expression in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and some human embryonic kidney cells.(Reference Sadri, Shu and Kachman15)

Milk and dairy intake and neurodevelopment and growth in infants and children

The milk fat globule membrane and infant neurodevelopment

The milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) is a highly complex three-layered membrane on the surface of milk fat globules. Whilst its primary role is to protect milk fat globules from digestion to maintain the milk emulsion, it contains a wide range of functional components including glycolipids (cerebrosides, gangliosides) and a range of polar phospholipids (PL) including phosphatidylethanolamine (32.0 ± 0.5 % of total PL), phosphatidylcholine (25.1 ± 0.4 % of total PL) and sphingomyelin (22.6 ± 0.5 % of total PL).(Reference Thum, Roy and Everett16) There are now many publications which describe the structure of the MFGM in detail including the recent one of Nie et al. (Reference Nie, Zhao and Wang17) It has been known for some time that gangliosides are involved in a wide range of neural functioning including transmission. A range of studies reviewed by Palmano et al.(Reference Palmano, Rowan and Guillermo18) highlighted that gangliosides are critical for neurone and brain development, for the development of functional synapses and nerve systems needed for memory and learning. This also highlighted the probable benefit of dietary gangliosides in the early postnatal period when brain development is incomplete.

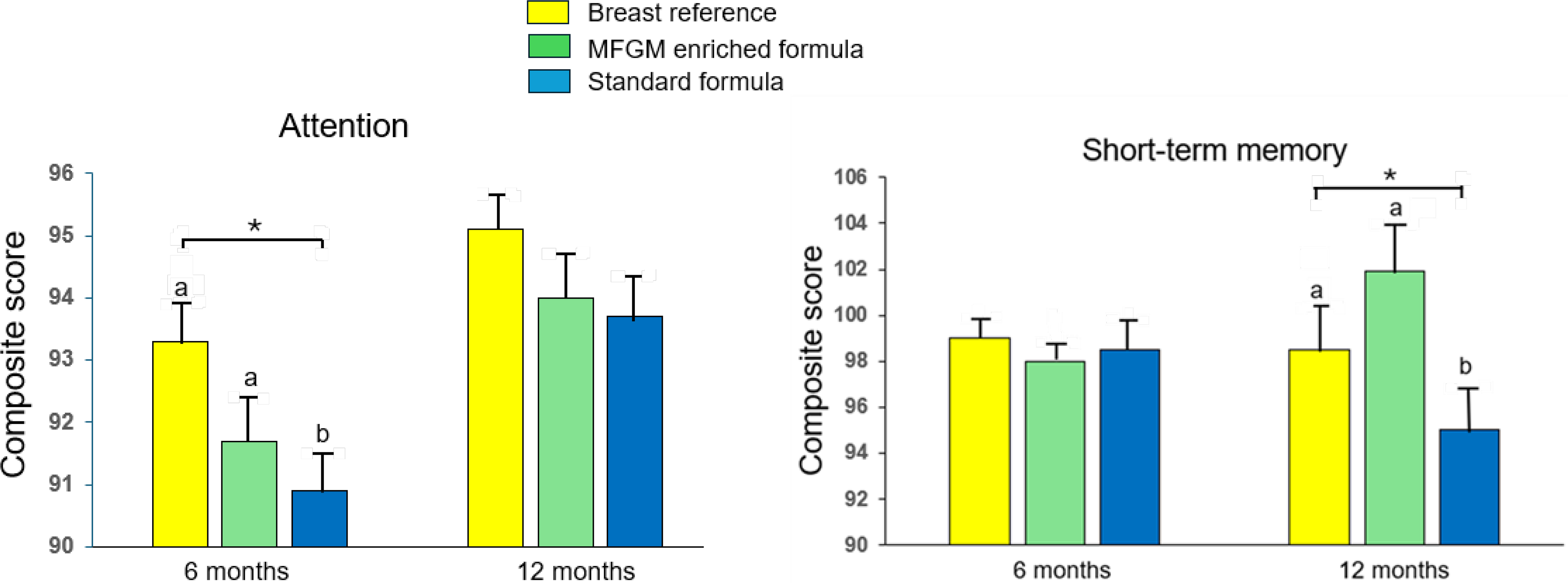

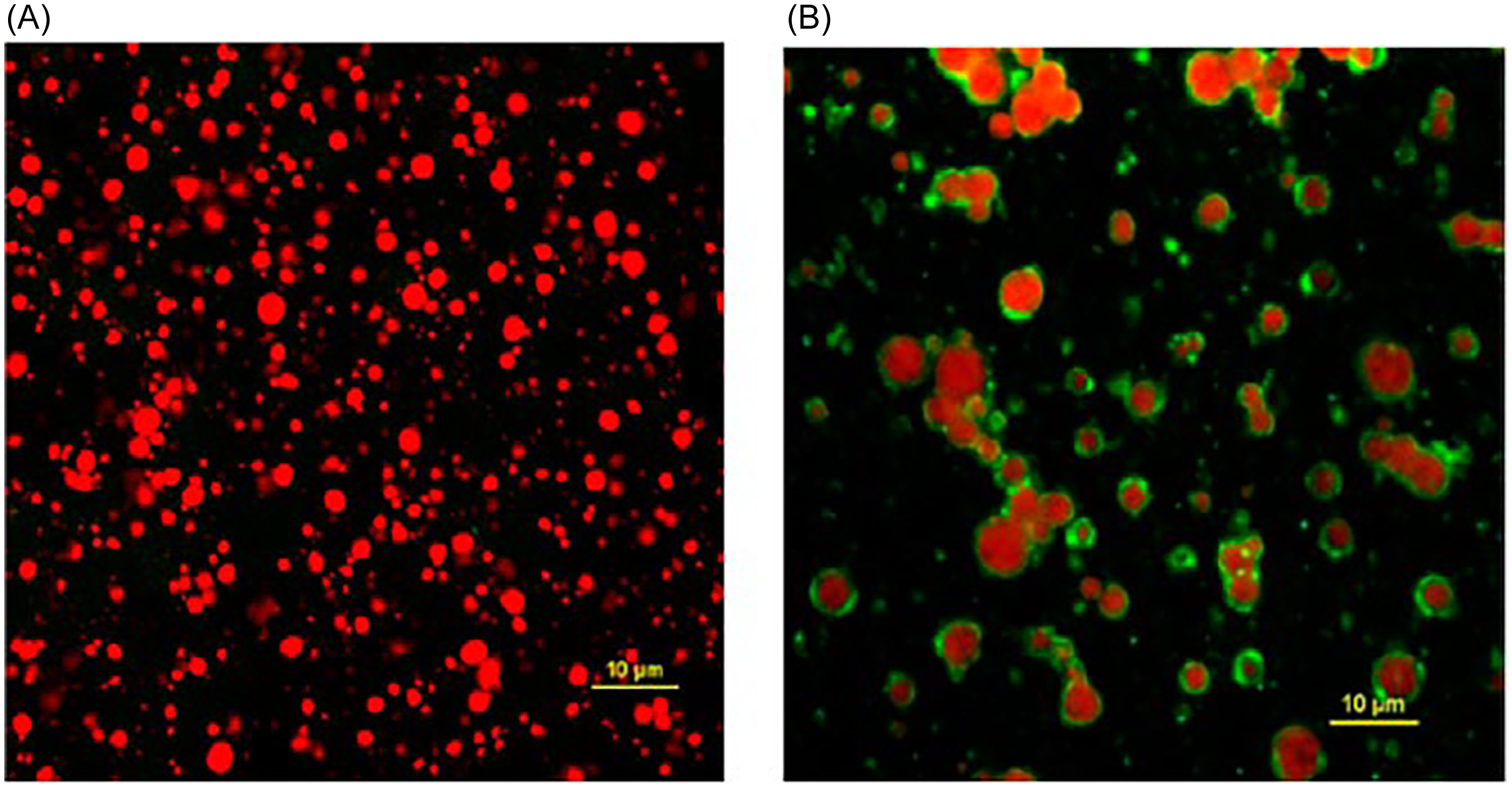

An early study(Reference Timby, Domellöf and Hernell19) involved a double-blind randomised controlled trial (RCT) with 160 infants <2 months of age who were randomly assigned to a MFGM-supplemented formula or a standard formula until 6 months of age. A separate 80 infants were breastfed as a control. At 12 months of age, the mean cognitive score of the MFGM treatment was significantly (P = 0.008) higher than that of the standard formula treatment but was not different (P = 0.73) to the breast-fed control. More recent work(Reference Xia, Jiang and Zhou20) showed a similar result. In a multi-centre double-blind RCT with 212 healthy infants (<14 days old) randomised to either standard formula, MFGM enriched formula or breastfed control for two consecutive 6-month periods showed breast and MFGM enriched formula gave significantly (P < 0.05) higher attention score after 6-months than those on the standard formula with the same ranking of treatments for short-term memory at 12-months (Figure 1). A recent review of the nature of the MFGM and its role in infant health and development supports the addition of MFGM to infant formulae as it is safe and warranted by recent clinical evidence.(Reference Brink and Lönnerdal21)

Figure 1. Benefits of MFGM enriched formula for infant neurodevelopment.

Source: Constructed with permission from(Reference Xia, Jiang and Zhou20) Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition Vol. 30. Xia Y, Jiang BW, Zhou LH et al. Neurodevelopment outcomes of healthy Chinese term infants fed infant formula enriched with bovine milk fat globule membrane for 12 months – A randomized controlled trial. Pages 401–414.

* P < 0.05, a, b, different letters denote significant difference (P < 0.05).

Milk, dairy foods and growth in childhood

The benefits of milk in childhood diets have been known for many years. For example, in 1926, a report by the UK Medical Research Council showed that giving an additional 568 mL/day of milk to boys in a children’s residential home led to a marked increase in growth. It has also been known for a long time that undernutrition in childhood can lead to a marked reduction in linear growth (stunting) which is associated with poorer cognitive development, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, elevated blood lipids and obesity in adulthood. Despite recent worldwide improvements, stunting prevalence in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and most of India remains >40 % which makes a substantial contribution to childhood mortality.

More recently, it has been emphasised that milk has a specific growth promoting effect in children, an effect seen in both developing and developed countries, with a response even when energy and nutrient intake are apparently otherwise adequate. The effect of milk on linear growth is now thought to be primarily mediated through the stimulation of hepatic IGF-1 by milk proteins.(Reference Hoppe, Mølgaard and Dalum22–Reference Young, Metcalfe and Gunnell24) The study of Hoppe et al.(Reference Hoppe, Mølgaard and Dalum22) in pre-pubertal boys indicated that of the milk proteins, casein provided the greatest response in IGF-1, although a recent study(Reference Watling, Kelly and Tong25) with middle-aged adults in the UK Biobank showed that protein from milk and yoghurt was strongly associated with circulating IGF-1 concentrations, but with no association with protein from cheese. Cheese contains virtually no whey protein which is present in milk and yoghurt suggesting that whey protein probably also stimulates IGF-1, at least in adults.

IGF-1 is now known to be essential for longitudinal bone growth, skeletal maturation and bone mass acquisition not only during growth but also in the maintenance of bone mineral density in adults, with regulation of bone length associated with changes in chondrocytes of the proliferative and hypertrophic zones of the growth plate.(Reference Yakar, Werner and Rosen26) Higher circulating concentrations of IGF-1 have also been associated with increased risk of colorectal and other cancers but conversely, as discussed later, milk and dairy are associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).

Milk and dairy intake and bone health in adolescents

Adolescence is the life stage (10–19 years) in which children transition into adults. Adolescence is a period of major changes including rapid growth, hormonal changes and the associated development of sexual maturation. Adolescence is also associated with increasing independence from parental influence, and this is often reflected in changing dietary habits. The age of onset of puberty has reduced substantially over the last 100 years and currently in the UK the average age for males and females is 12 and 11 years respectively according to NHS records. Crucially, adolescence is the period of maximum bone mineral accretion rate which becomes rapid around the time of puberty and reaches its maximum a little after maximum height gain.(Reference Weaver, Gordon and Janz27)

The UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) has shown that adolescent females, reduce milk consumption substantially and increased intake after the age of 19 years is slow.(28) This is likely related to the NDNS in recent decades also showing substantially sub-optimal intakes of Ca, Mg and other dairy-rich nutrients. The most recent NDNS (Years 2019–23)(29) reports that 18 and 48 % of adolescent females (11–18 years of age) have intakes of Ca and Mg respectively, below the Lower Reference Nutrient Intakes for these nutrients, somewhat greater values than the previous NDNS period (2016–17). Adolescent males also have sub-optimal intake of these nutrients but somewhat less than females. The very low intakes of Mg are particularly worrying given the evidence concerning the association between Mg and bone mineralisation with low status being linked to progression of osteoporosis.(Reference Liu, Luo and Wen30)

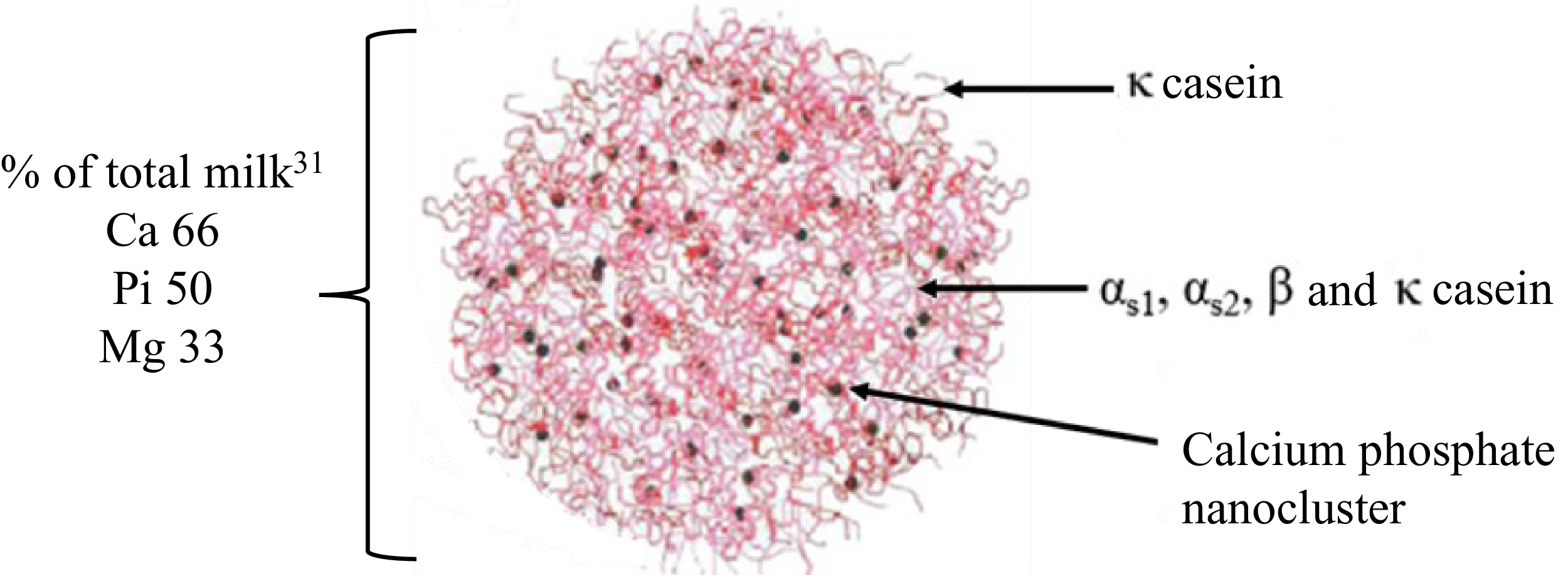

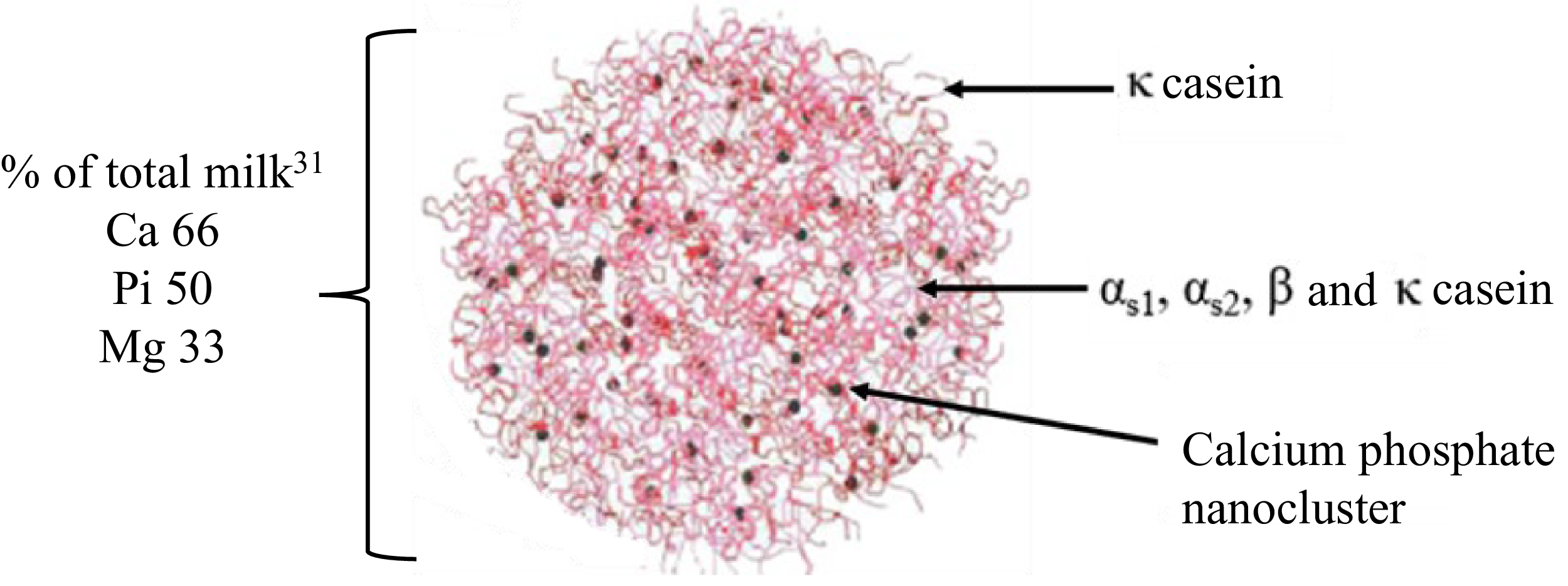

Given the low intakes of milk by adolescents it is fortunate that milk possesses a unique delivery system for Ca, Mg and P, notably the casein protein micelle without which Ca and Mg intakes would be even lower. As described by Grewal et al.,(Reference Grewal, Vasiljevic and Huppertz31) ‘casein micelles are colloidal complexes of four types of casein proteins (aS1-, aS2-, b- and k-CN) held together by amorphous calcium phosphate, electrostatic and hydrophobic forces’ (Figure 2). Critically, casein micelles contain Ca-P at supersaturated concentrations.(Reference Holt32) They deliver to the digestive tract about 66, 50 and 33% of the total milk Ca, inorganic P and Mg respectively. The functionality of the casein micelle has been exploited for other nutritional uses. Cohen et al.(Reference Cohen, Levi and Lesmes33) developed a process for preparing reconstituted casein micelles loaded with vitamin D3. Using an in vitro digestion model, they showed that the encapsulated vitamin D3 was protected during gastric and early duodenal phases (∼85 % retained) compared with the control of vitamin D3 dispersed in water (∼15 % retained; P < 0.05). The use of Caco-2 cells to assess vitamin D bioavailability showed no significant effect relative the control but due to the protection during gastric digestion, the overall bioavailability of casein loaded vitamin D was four times greater than that in the control.

Figure 2. Model of the casein micelle showing the % of total milk Ca, inorganic P and Mg it contains.

Source: Casein micelle model reprinted from Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, Vol. 171, de Kruif CG, Huppertz T, Urban VS, Petukhov AV. Casein micelles and their internal structure, Pages 36–52,(Reference De Kruif, Huppertz and Urban88) © 2012, with permission from Elsevier.

Overall, there is consistent evidence of a beneficial association between milk/dairy consumption and bone health, particularly fermented dairy in some studies.(Reference Rizzoli34) Recently an umbrella review of meta-analyses using data from RCTs, showed particularly milk to be associated with higher bone mineral density and content. Cohort studies for fracture risk were inconsistent for total dairy and milk but cheese and yoghurt showed greater protective effects.(Reference Sharifan, Roustaee and Shafiee35) Many of the studies used showed high heterogeneity which may explain the variation in outcomes seen. In addition, this study used data from adults; there is a clear need for more studies on the impact of underconsumption of bonetrophic nutrients during adolescence on risk to bone health in later life and particularly in the post-menopausal period in women. This is particularly critical if adolescents, females in particular, begin a further transition towards greater consumption of vegan or related diets which are known to increase the risk of total fractures, hip and leg fractures(Reference Tong, Appleby and Armstrong36)

Milk and dairy intake and health in middle age

Whilst diet in early life can impact on later health, middle age (40–60 years old) is the period when several diet-responsive chronic conditions are more likely to emerge. Data from a follow-up study(Reference Gondek, Bann and Brown37) with subjects in 1970 British Cohort Study now aged 46–48 years, confirmed that mid-life morbidity was particularly related to diabetes and hypertension both of which substantially increase the risk for CVD. In most Western countries over the last 30 years mortality from CVD has substantially fallen yet this remains the major mortality cause. This review will focus on associations between dairy foods and CVD, blood pressure and the role of GLP-1.

Association milk and dairy consumption with cardiovascular diseases

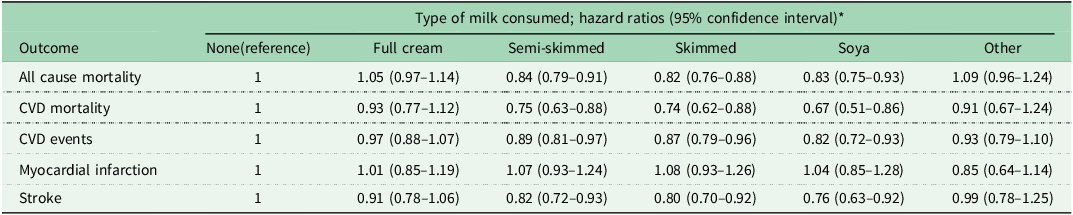

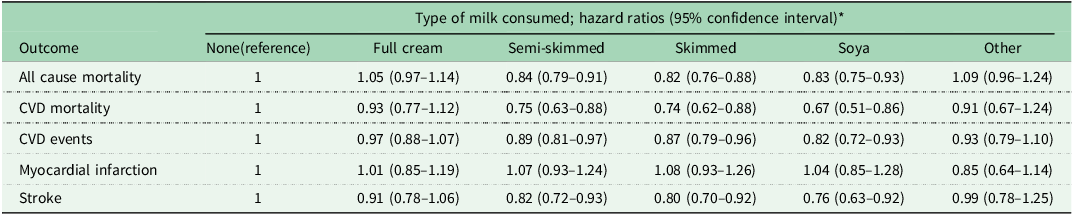

Results from many prospective studies, related reviews and meta-analyses have been published in recent decades and broadly show milk and dairy foods to have neutral or somewhat beneficial association with CVD. A study using data from 450,507 subjects in the UK Biobank,(Reference Zhou, Wu, Lin and Wang38) reported on the association between milk consumption and risk of CVD events and all-cause mortality over a median follow-up period of 12 years. A summary of the results is given in Table 1. The multimode model showed that compared to non-consumers of milk, semi-skimmed and skimmed milk were significantly associated with a reduced risk of all-cause and CVD mortality while full-cream milk was not significantly associated with either outcome. Similarly, semi-skimmed and skimmed milk were associated with reduced risks for CVD events and stroke but not for myocardial infarction (MI) which was neutral.

Table 1. Associations of milk type and risk of all-cause mortality and CVD outcomes

Source: Derived from(Reference Zhou, Wu, Lin and Wang38) * All based on the multivariate model.

The umbrella study of Fontecha et al.(Reference Fontecha, Calvo and Juarez39) which involved of 17 meta-analyses of prospective studies and 12 for RCT, concluded that the consumption of total dairy foods with either normal or reduced fat content does not negatively impact the risk of CVD or heart failure. They also found an inverse association of dairy food intake and ischaemic heart disease and MI, and for fermented dairy (cheese, fermented milk and dairy foods) and non-fatal and fatal stroke. Another very recent umbrella study involved 26 meta-analyses on dairy and the risk of CVD.(Reference Sharifan, Roustaee and Shafiee40) Their subsequent updated meta-analyses indicated that total dairy (RR, 0.96, 95 % CI: 0.93–0.99), milk (RR, 0.97, 95 % CI: 0.941–0.998) and yoghurt (RR, 0.92, 95 % CI: 0.87–0.98) were all significantly associated with reduced risk of CVD. Milk and fat-reduced dairy were associated with reduced risk of stroke.

The generally neutral or beneficial health affects with increased consumption of milk/dairy foods is despite most of these foods often making the major contribution to SFA intake. To many, this has not only been counterintuitive, but contrary to the traditionally believed, well-established diet-heart hypothesis linking SFA intake with plasma low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and CVD. A fuller discussion of this has been presented earlier(Reference Givens41) but two key aspects related to dairy underlying functionally which likely contribute to the beneficial effects are discussed below.

Milk and dairy foods and hypertension and vascular function

The Health Survey for England 2022 shows that the prevalence of all types of hypertension (defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg; diastolic pressure ≥90 mm Hg) was 15, 26, 40% for men and women combined aged 35–44, 45–54 and 55–64 years old respectively.(42) This highlights the increased prevalence in middle/late middle age. Early studies developing the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet demonstrated that when low-fat dairy (2.0 v. 0 servings/ day) plus regular-fat dairy (0.7 v. 0.3 servings/day) were added to the fruits and vegetables diet (to give the combination diet) this gave rise to significantly reduced (P = 0.001 for both) systolic (−2.7 mm Hg) and diastolic (−1.9 mm Hg) blood pressures over an 8-week intervention period.(Reference Appel, Moore and Obarzanek43) The combination diet had a higher protein concentration than the fruits and vegetables diet (17.9 v. 15.1% total energy intake) which is probably relevant.

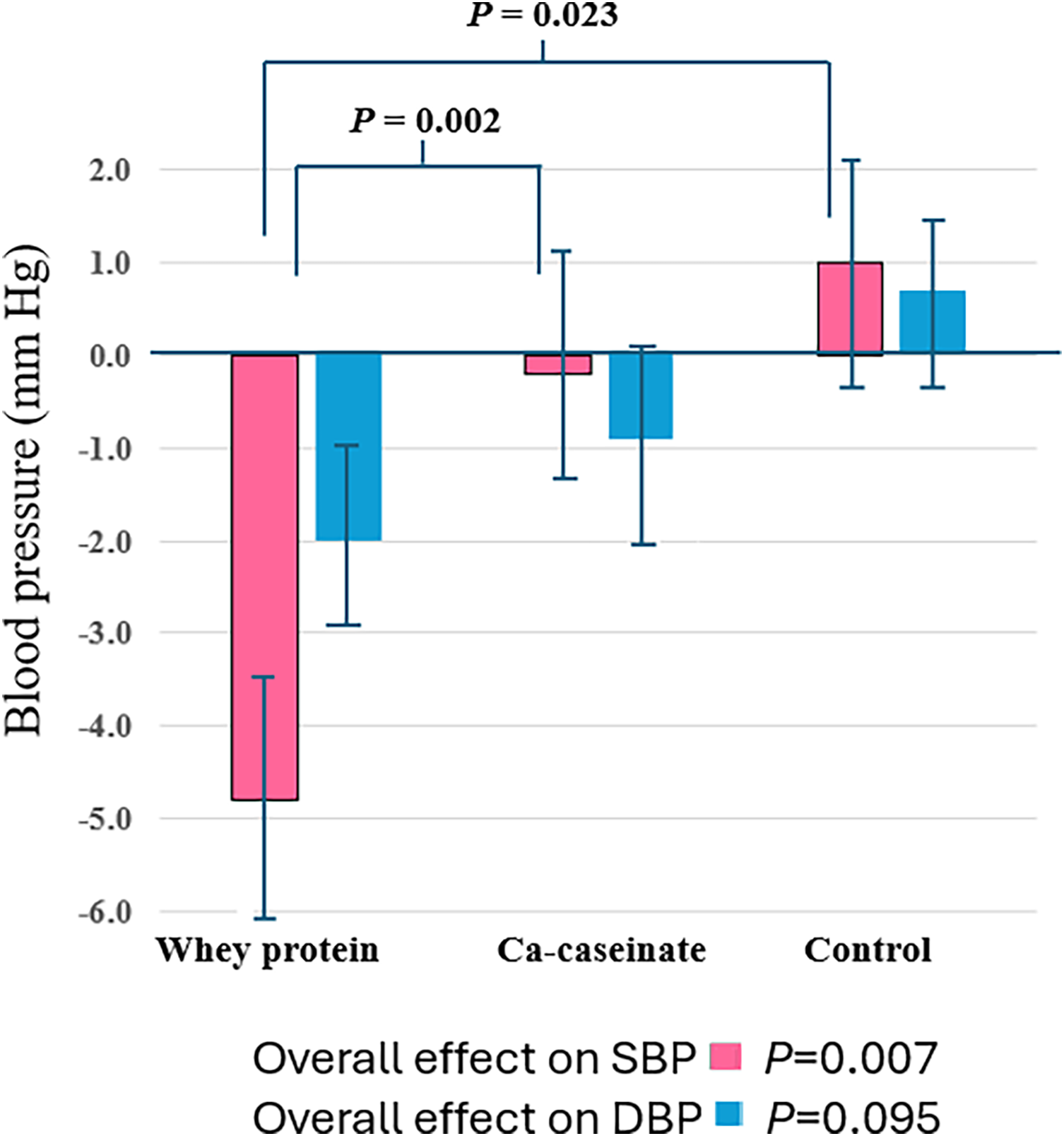

There is now good evidence that some of the peptides released from milk proteins (whey proteins, casein) during digestion have beneficial hypotensive effects. For example, an 8-week RCT found that whey protein isolate (2× 28g/day) had a larger hypotensive effect than casein, with effects seen on both central and peripheral blood pressures(Reference Fekete, Giromini and Chatzidiakou44) (Figure 3.) Whey protein was also shown to have a greater effect than casein in an acute setting. A number of mechanisms by which milk and its components could lower blood pressure have been proposed including the effects of some milk protein-derived peptides in particular. A number of these peptides released during digestion of casein and whey proteins possess hypotensive properties through inhibiting the angiotensin-1-converting enzyme (ACE) that would normally increase the production of angiotensin-II which has a vasoconstricting effect via the AT1 receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells leading to increased blood pressure. There are now databases of milk bioactive peptides including the one created at Oregan State University.(Reference Nielson, Beverly and Qu45) The effects of ACE inhibition are consistent with lower blood pressure being associated with milk and dairy in prospective studies.(Reference Cohen, Levi and Lesmes33) Since hypertension is a key risk factor for CVD, and stroke in particular, the hypotensive effects of milk protein peptides are consistent with the neutral or beneficial findings in many prospective studies.

Figure 3. The effects of whey protein, Ca-caseinate and carbohydrate control on peripheral systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Source: Constructed from(Reference Fekete, Giromini and Chatzidiakou44).

Research on haemodynamics has shown that arterial stiffness, especially of the central large arterial vessels, is a valuable predictor of future CVD events. In a long-term prospective study milk and dairy consumption was shown to be significantly (P = 0.021) associated with reduced arterial stiffness based on a reduced aortic pressure augmentation index (Alx).(Reference Livingstone, Lovegrove and Cockcroft46) This was extended in a 4-week RCT where the effect of exercise together with milk proteins were examined with hypertensive and obese young women.(Reference Figueroa, Wong and Kinsey47) They were randomised to consume whey protein (30 g/day), casein (30 g/day) and a control of maltodextrin. Compared with the control, whey protein and casein both significantly (P < 0.05) reduced pulse wave velocity (by 57 and 53 cm/s respectively), Alx (9.2 and 8.1 % respectively) indicating that both proteins reduced arterial stiffness. Both proteins also significantly (P < 0.05) reduced brachial and aortic systolic but not diastolic blood pressure. The exercise component was shown not to have had additional benefits on vascular function or blood pressure.

The impact of the dairy food matrix

In recent times there has been increasing interest in the so-called food matrix since it is known that food processing, which alters its physical matrix can, for example, alter the rate at which carbohydrates are digested. The food matrix that has been the most studied is dairy since there is increasing evidence that its matrix effects can alter the postprandial change in blood lipids.(Reference Thorning, Bertram and Bonjour48)

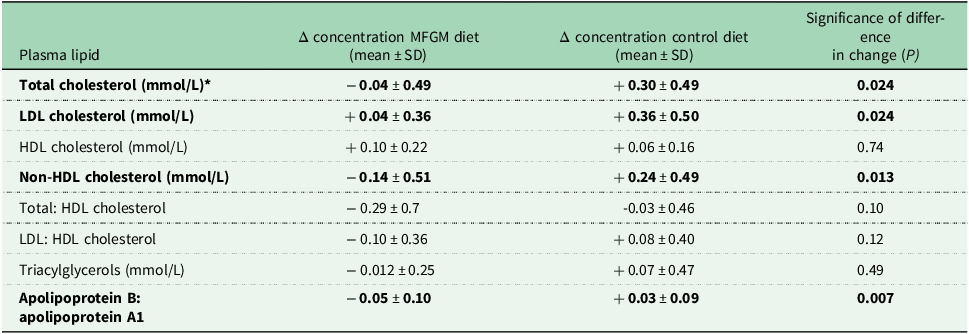

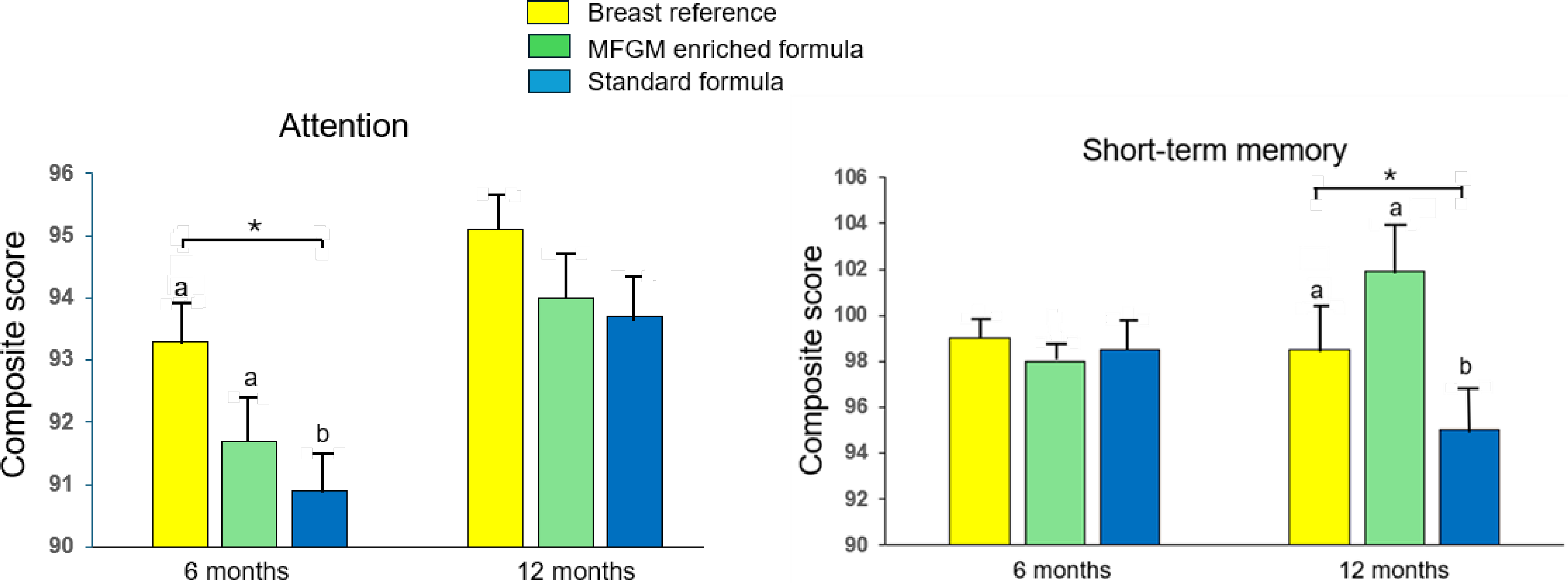

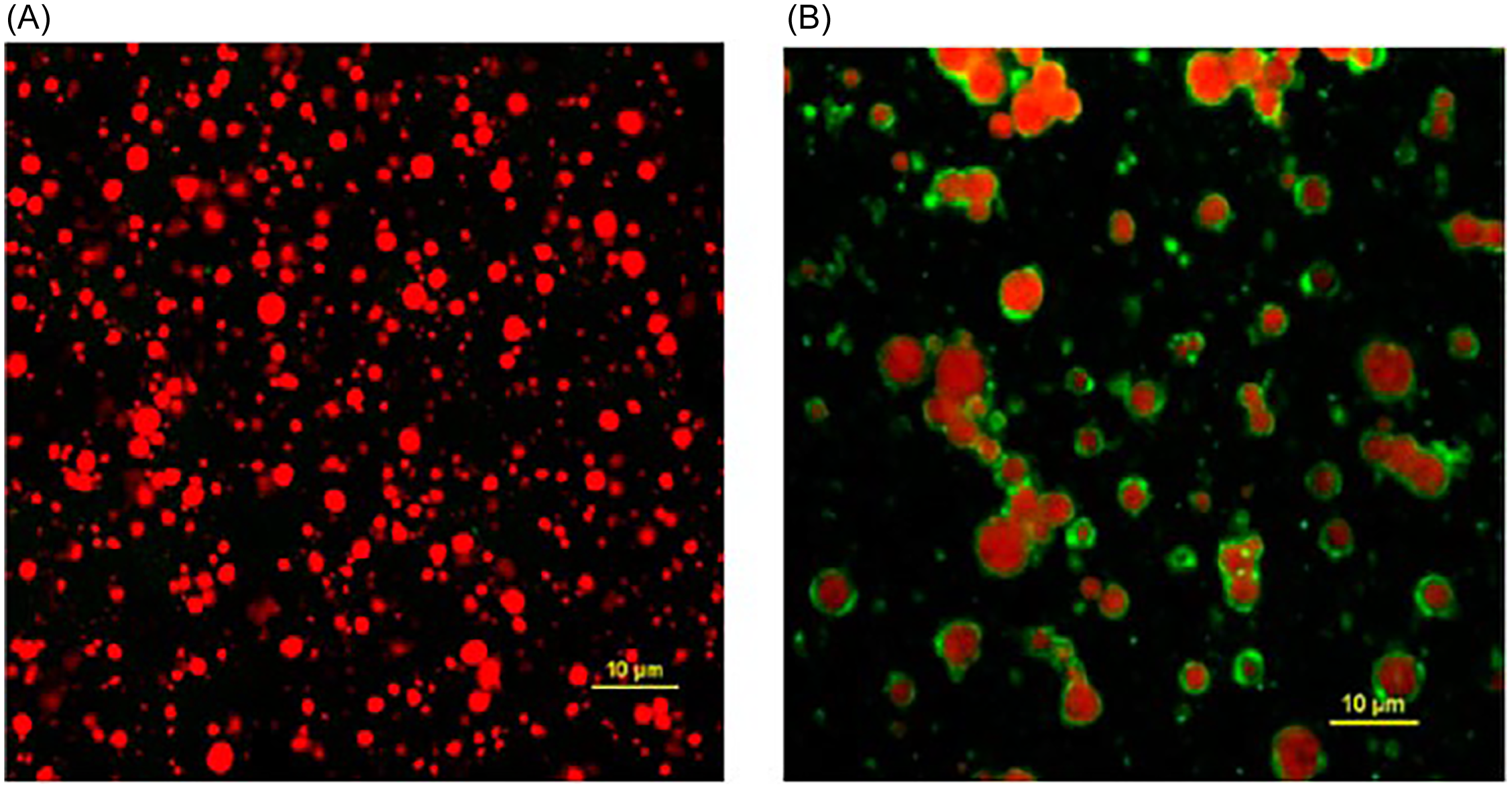

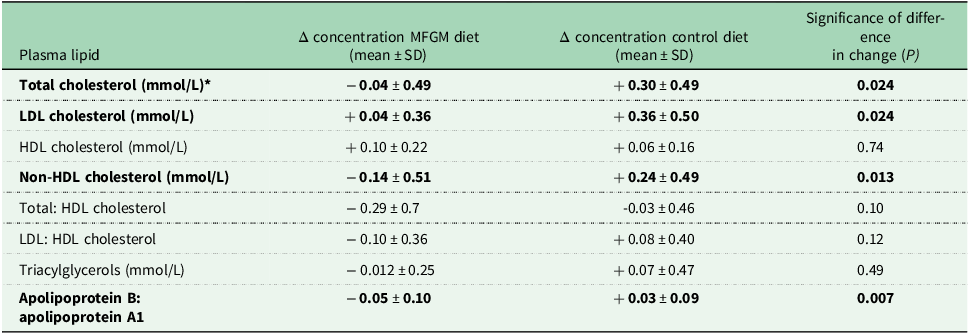

A good example of this effect is shown by the RCT of Rosqvist et al.(Reference Rosqvist, Smedman and Lindmark-Månsson49) which involves another feature of the MFGM. This was an RCT of 8-weeks duration where two parallel groups of overweight men and women were randomly assigned to consuming 40g of milk fat/day as either whipping cream or butter oil. The key difference was in the whipping cream the MFGM were relatively intact whereas in the butter oil the MFGM was essentially non-existent (Figure 4). As perhaps predicted, the butter oil treatment significantly increased plasma total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol relative to the whipping cream (Table 2). These were consistent with the significant reduction in plasma apolipoprotein B: apolipoprotein A1 ratio in the MFGM treatment relative to the control.

Figure 4. Confocal laser micrographs of A) milk fat from butter oil and B) milk fat from whipping cream. Milk fat is red, MFGM is green.

Source: Reprinted from American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Vol. 102, Rosqvist F, Smedman A, Lindmark-Månsson H et al., Potential role of milk fat globule membrane in modulating plasma lipoproteins, gene expression, and cholesterol metabolism in humans: a randomized study, Pages 20–30,(Reference Rosqvist, Smedman and Lindmark-Månsson49) © 2015, with permission from Elsevier.

Table 2. Effect of 40g fat/day for 8-weeks from whipping cream (MFGM) or butter oil (Control) on change in plasma lipids

Source: Derived from(Reference Rosqvist, Smedman and Lindmark-Månsson49)* Bold lines indicate significant difference between treatments.

There was no effect on HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio and triacylglycerols. The study(Reference Rosqvist, Smedman and Lindmark-Månsson49) shows the intact MFGM can protect the triacylglycerols in its core from lipase activity and hence minimising their effect on blood lipid concentrations.

The effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists

Since traditional treatments for obesity tend to be used only for short periods and can give disappointing results, there has been a marked increase in the therapeutic use of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Typically, these have few serious side effects and a broader range of benefits. Essentially, they attach to the cell receptors and provide the same effect as the GLP-1 hormone in a dose-response fashion. The beneficial effects of GLP-1 include insulin stimulation, inhibition of glucagon production, reduced gastric emptying and increased satiety leading to improved glycaemic control and reduced adiposity. They are therefore helpful for type 2 diabetics(Reference Nachawi, Rao and Makin50) although there are some concerns that they may reduce lean body mass which could impair glycaemic control.(Reference Ceasovschih, Asaftei and Lupo51)

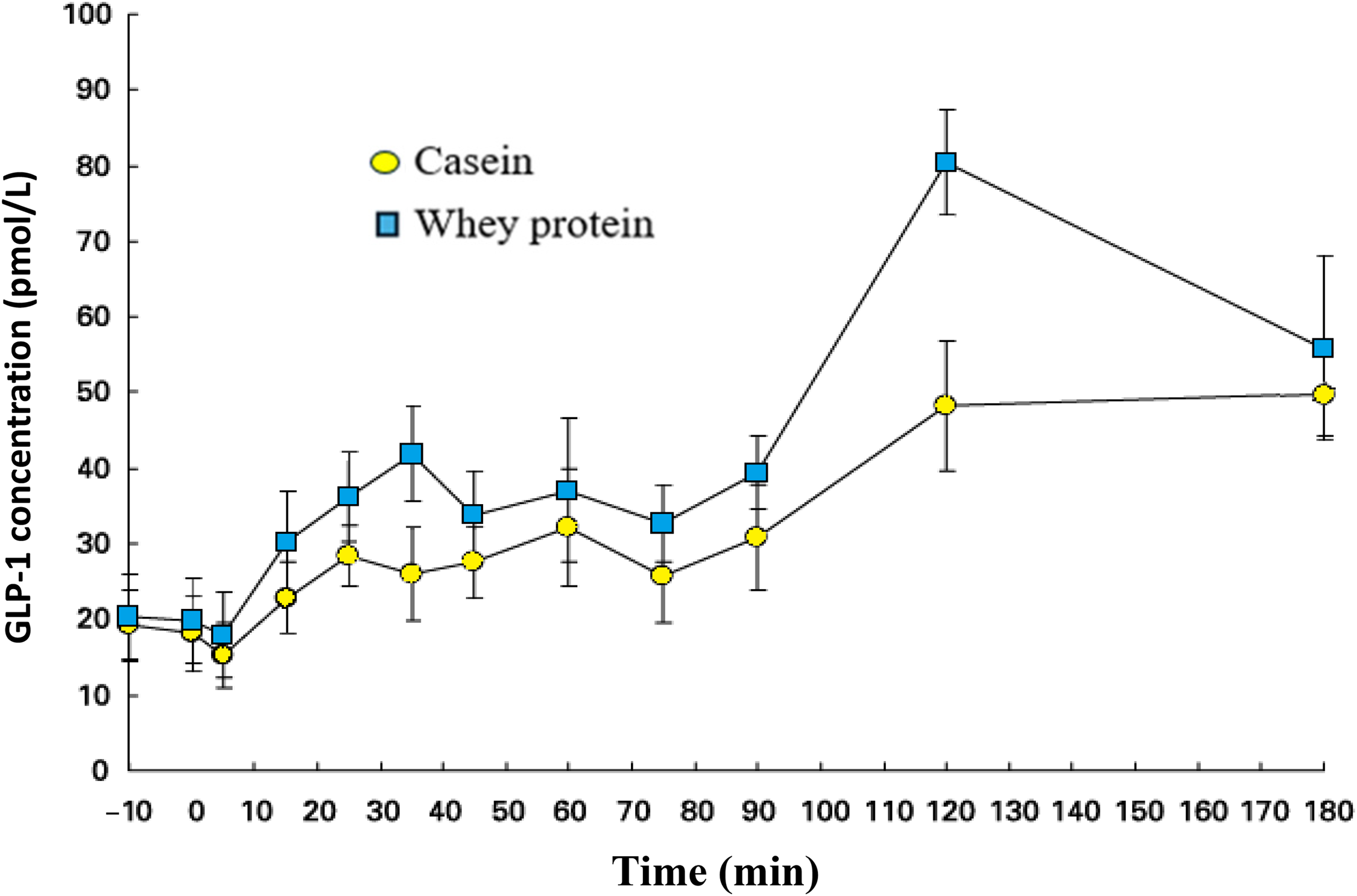

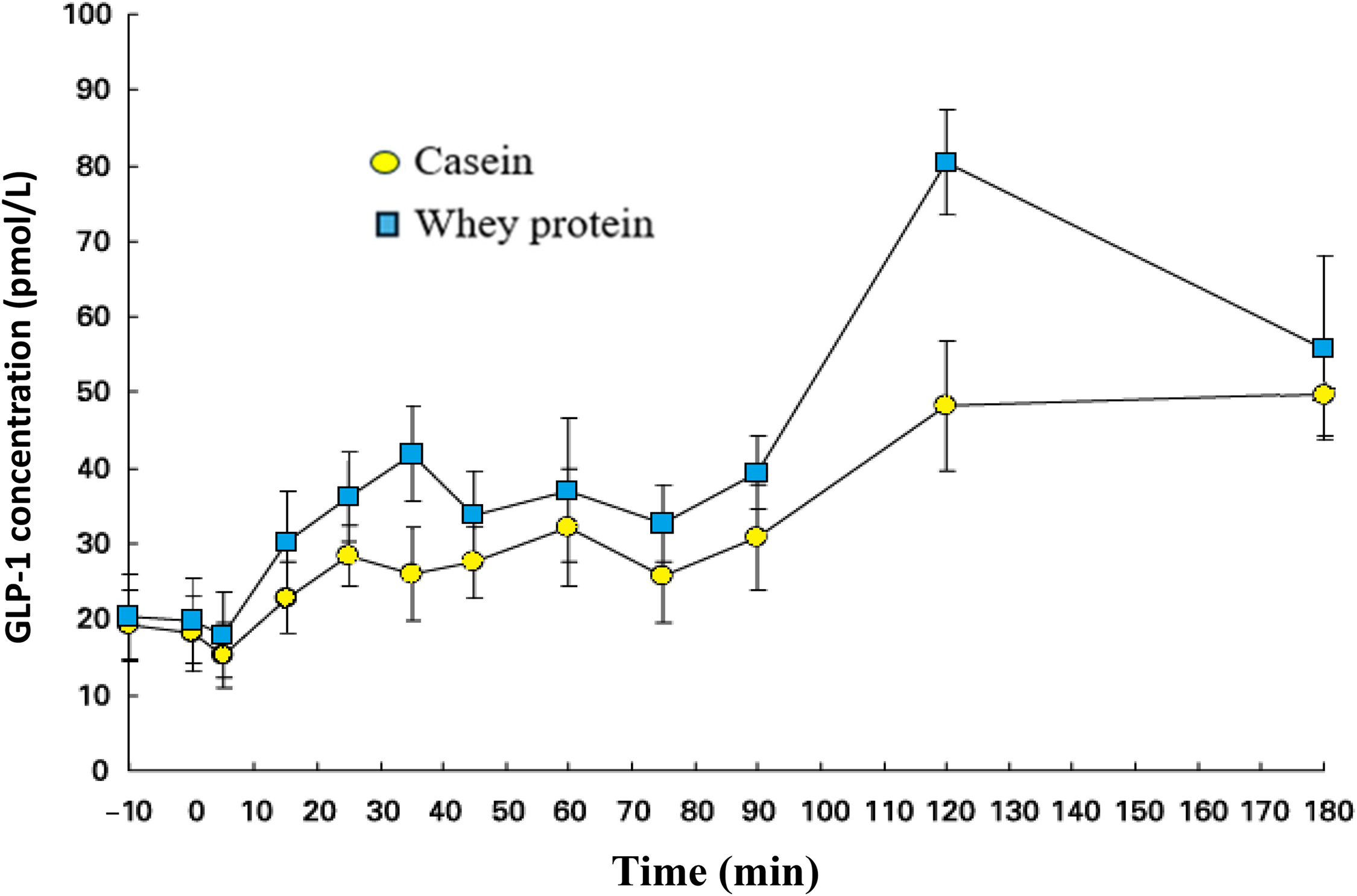

There is considerable evidence that milk proteins can stimulate GLP-1 secretion. A cell-based study showed that equal concentrations of skim milk and casein significantly (P < 0.05) stimulated GLP-1 release in a dose-responsive manner and whilst whey protein did increase GLP-1 release it did not reach significance.(Reference Chen and Reimer52) These findings contrasted with a human postprandial study (0 to 180 minutes) which involved a preload of either 48g of whey protein or casein. The whey protein was more satiating and led to a higher (P < 0.05) postprandial circulating concentrations of GLP-1, than the casein preload(Reference Hall, Millward and Long53) (Figure 5). A meta-analysis of 35 RCTs(Reference Sepandi, Samadi and Shirvani54) found that whey protein supplementation compared to the control significantly reduced body weight, BMI and body fat mass which is consistent with a contribution from GLP-1. Similarly, the inverse association of some dairy foods, notably yoghurt with type 2 diabetes,(Reference Guo, Givens and Astrup55) is also consistent with the effects of GLP-1.

Figure 5. Effect of preloads of 48 g of casein or whey protein on plasma GLP-1 concentrations. Values are means ± standard errors.

Source: Reuse from Hall WL, Millward DJ, Long SJ et al. (Reference Hall, Millward and Long53) Casein and whey exert different effects on plasma amino acid profiles, gastrointestinal hormone secretion and appetite, British Journal of Nutrition, 2003, 89, 239–248, 2007 © Cambridge University Press, reproduced with permission.

Milk and dairy intake and health in later life

Progression into later life is associated with increased risk of several conditions. This review will consider the impact of bioactive components in milk/dairy products in relation to reducing the loss of skeletal muscle and the risks of impaired cognition/dementia and CRC.

Dairy proteins and skeletal muscle

Sarcopenia is a condition characterised mainly by a chronic loss of muscle mass and muscle strength with advancing age. It is therefore a condition of particular importance in the elderly (though not exclusively), with an increasing prevalence mainly associated with both the increasing age and obesity of populations worldwide. The global prevalence of sarcopenia varies considerably between studies with pooled estimates for all definitions of sarcopenia estimated about 10 % (95 % CI: 7–12 %) in one study(Reference Carvalho do Nascimento, Bilodeau and Poitras56) and 16 % (95 % CI: 15 –17 %) in another.(Reference Petermann-Rocha, Balntzi and Gray57) Sarcopenia can have far reaching consequences since, for example, it reduces bone protection increasing the risk of breakage in a fall leading to reduced mobility, disability and lower quality of life. A less well recognised outcome of reduced muscle mass and possibly associated reduced exercise ability is the increased risk of metabolic diseases, particularly insulin resistance leading to type 2 diabetes. This is mainly because skeletal muscle is a key regulator of glucose homeostasis being responsible for uptake and oxidation of some 80% of postprandial circulating glucose(Reference Merz and Thurmond58)

Wall et al. reviewed the then available research data on the relative anabolic effects of specific protein types.(Reference Wall, Cermak and van Loon59) Their main conclusion was that proteins such as whey protein which are rapidly digested and absorbed lead to greater muscle protein synthesis than from slower digested proteins like casein and those in soya preparations. They also found that even when casein is pre-hydrolysed to increase digestion rate, the muscle protein response is still smaller than from equivalent amounts of whey protein. This is mainly attributed to the higher leucine content of whey protein; the specific effect of leucine having also been seen in studies using leucine supplements.(Reference Xu, Tan and Zhang60) It is an important activator of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) a nutrient-sensing signalling pathway in skeletal muscle. In addition, leucine is insulinotrophic and the additional insulin enhances muscle protein synthesis. There is however evidence that consumption of 40g of casein before sleeping increases muscle protein synthesis rates overnight in older men.(Reference Kouw, Holwerda and Trommelen61) This is potentially important as overnight is generally a period of negative whole body protein balance.

Several studies have examined the relative value of plant proteins compared with whey protein. The study of Yang et al. compared the response in muscle protein fractional synthetic rate (FSR) in rested elderly men resulting from 0, 20 or 40 g of either whey protein or soya protein. Muscle FSR did not respond to consumption of 40 g soya protein compared with 20 g, but it responded to whey protein essentially in a linear fashion. A similar differential effect was seen when the protein supplements were given post-exercise(Reference Yang, Churchward-Venne and Burd62)

Although leucine is a dietary essential amino acid and hence a nutrient, its anabolic functionality is complex and arguably beyond its traditional role as component of protein. Its high concentration in milk proteins, whey protein especially, provides the functionality of dairy proteins for reducing the risk of this important condition.

Dairy products and colorectal cancer

As with all cancers, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) in collaboration with the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) have an ongoing surveillance project on the association between diet and risk of CRC. In 2007 they reported that that ‘milk consumption probably protects against colorectal cancer’ (RR 0.78, 95 % CI: 0.69–0.88)(63) which was updated in 2011 with a meta-analysis showing a 9% reduced RR of CRC per 200g milk/day.(64) This was followed by a systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 cohort studies representing about one million subjects, 11,579 of whom developed CRC.(Reference Aune, Lau and Chan65) The overall RRs were 0.83 (95 % CI: 0.78–0.88) per 400 g/day of total dairy products and 0.91 (95 % CI: 0.85–0.94) per 200 g/day of milk intake in good agreement with WCRF/AICR who published another update report in 2018(66) and a report in 2024(67) which ‘focuses on providing clarity on the evidence on how dietary and dietary and lifestyle patterns affect cancer risk’. The 2018 and 2024 reports concluded respectively ‘Strong probable evidence that dairy products (including total dairy, milk, cheese and dietary Ca) decrease the risk of CRC’ and ‘For colorectal cancer prevention, there is a specific recommendation to include calcium-containing foods (such as dairy products)’. Despite the reference to cheese above, there is little evidence for exposures specifically to cheese, yoghurt, fermented milk and butter.

Whilst the above evidence refers primarily to specific foods, the recent study of Papier et al. examined a diet-wide analysis on incident cases of CRC in 0.54 million women in the UK Biobank.(Reference Papier, Bradbury and Balkwill68) Of 97 dietary factors examined 17 were associated with the risk of CRC with alcohol and Ca intakes having the strongest positive and negative associations respectively (at highest Ca intake RR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.77–0.90). Milk at highest milk intake had RR 0.89, 95% CI: 0.84–0.94 with fruit and wholegrains also negatively associated. Milk and Ca intakes were naturally highly correlated but after adjustment for Ca, the inverse associations for milk and yoghurt were not significant. This suggests that Ca intake was independently associated with reduced risk of CRC, although in most diets, milk/dairy will be a substantial contributor to Ca intake.(Reference Papier, Bradbury and Balkwill68) Ca supplements were not investigated although an earlier meta-analysis of six cohort studies reported that 300 mg/day of supplementary Ca was associated with a 9% lower risk (RR 0.91, 95 % CI: 0.86–0.98).(Reference Keum, Aune and Greenwood69) Papier et al. (Reference Papier, Bradbury and Balkwill68) also proposed that a likely protective effect of Ca may be related to its ability to bind with bile acids and free fatty acids in the colon thus reducing their potential CRC impact. Interestingly, when milk intake was genetically predicted using Mendelian randomisation with the lactase polymorphism (SNP rs498823562 in the MCM6 gene) the risk of CRC was substantially lower (RR per 200 g/day 0.60, 95 % CI: 0.46–0.74) than when reported intake was used (RR per 213 g/day 0.92, 95 % CI: 0.87–0.98).(Reference Papier, Bradbury and Balkwill68) Clearly milk intake will be higher and over a longer period in lactose tolerant populations although the reasons for the much lower risk in them needs further examination.

Several other studies have examined the effect of dietary pattern on CRC risk. These include Chu et al.(Reference Chu, Lin and Croker70) which showed that high-dairy, high fruit and vegetable and low-alcohol dietary patterns were associated with reduced risk of CRC (RR 0.76, 95%CI: 0.60–0.97) and particularly rectal cancer (RR 0.56, 95 %CI: 0.37–0.84). This contrasts with a study comparing diets containing animal or plant protein at usual intakes using data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1988–1994, which showed an inverse association between cancer mortality and animal protein (Hazard ratio (HR) 0.95, 95 % CI: 0.91–1.00) but a neutral association with plant protein (HR 1.08, 95 % CI: 0.93–1.24).(Reference Papanikolaoua, Phillips and Fulgoni71) There was no differentiation of foods within the two patterns and risk of CRC was not specifically examined. The study did however show no effect of circulating IGF-1 on cancer mortality in any age group despite other evidence that protein intake was associated with increased IGF-1 concentration which has been linked to increased risk of CRC.(Reference Rinaldi, Cleveland and Norat72)

Overall, the evidence for milk/dairy being associated with a reduced risk of CRC is strong although there remains uncertainty if this is mediated entirely by Ca from any dietary source.

Dairy foods and the milk fat globule membrane, cognition and dementia

Age and sex standardised data for England and Wales has shown that dementia incidence reduced by 28.8% from 2002 to 2008 (incidence rate ratio (IRR) 0.71, 95% CI: 0.58–0.88) but subsequently rose by 25.2% from 2008 to 2016 (IRR 1.25, 95% CI: 1 . 03–1 . 54).(Reference Chen, Bandosz and Stoye73) The study estimated that if the upward trend to 2016 continued there would ∼1.7 million cases of dementia by 2040. The risk and prevalence rates for dementia, of which Alzheimer’s disease represents ∼60–70%, increase substantially with age with some 17% of UK subjects over 80 years of age currently being affected.(74) Whilst a decline in cognitive performance is a normal part of ageing, this can decline rapidly in those who progress to develop dementia. Given the rising prevalence rate and the high psychological and emotional impact of dementia for the patient, family and carer, it is vital that research activity increases and options including dietary means of reducing the prevalence rate and/or delaying the age of onset are found.

Several studies have examined the associations between milk/dairy and cognition/dementia. With 17 074 survivors of the atomic bombing in Japan, Yamada et al. investigated the association between midlife risk factors and vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease 25 to 30 years later.(Reference Yamada, Kasagi and Sasaki75) This showed that vascular dementia increased with age and with low milk intake, with almost daily consumption being associated with significantly lower risk of vascular dementia (P = 0.002). There was no association between milk consumption and Alzheimer’s disease. Another Japanese cohort study(Reference Ozawa, Ohara and Ninomiya76) with dementia-free subjects aged ≥ 60 years at baseline who were followed up for 17 years reported that milk/dairy were negatively associated with Alzheimer’s disease (HR 0.63, 95% CI: 0.41–0.98, P trend = 0.03, highest vs. lowest quartile, fully adjusted model). There were no significant associations with all-cause and vascular dementia when comparing highest v. lowest milk/dairy intake quartiles although there were some between lowest and quartile-3 for all-cause dementia (P = 0.03), and lowest and quartile-4 for vascular dementia (P = 0.01), both using the model adjusted only for age and sex.

A more recent cohort study with 2497 dementia-free Finnish men at baseline were followed up for 22 years to assess associations of dairy, meat and fish intakes on the risk of dementia and cognitive performance.(Reference Ylilauri, Hantunen and Lönnroos77) Among the foods, only cheese (>31 g/day) showed a significant protective association for dementia (HR 0.72, 95 % CI: 0.52–0.99, P trend = 0.05) with overall, each 50 g of cheese was associated with 20 % lower risk of incident dementia. In the tests of cognition, higher intakes of non-fermented dairy foods and milk were associated with poorer verbal fluency. Of concern was the finding that for subjects with the Apolipoprotein E (APOE)-ɛ4 genetic variant, non-fermented dairy foods were associated with a 5% (95 % CI: 1–9%) higher risk of dementia per additional 50g/day. In contrast, data from the Japanese Ohsaki cohort study(Reference Lu, Sugawara and Tsuji78) showed that while cheese was associated with an increased risk of dementia (HR 1.28, 95 % CI: 0.91–1.79 fully adjusted model), yoghurt and other fermented dairy products were associated with a reduced dementia risk (HR 0.89, 95 % CI: 0.74–1.09 fully-adjusted model).

In recent years there has been an increasing number of studies on the potential of the MFGM and/or its components to reduce cognitive decline and dementia in the elderly. Recent reviews on this topic include those of Schverer et al.,(Reference Schverera, O’Mahonya and O’Riordana79) O’Callaghan et al. (Reference O’Callaghan, McCarthy and Carey80) and Luque-Uría et al.(Reference Luque-Uría, Calvo and Visioli81) Several studies on cognitive decline have been undertaken using aged rats including those which found that feeding an MFGM-rich concentrate modulated miRNA expression,(Reference Crespo, Tomé-Carneiro and Gómez-Coronado82) improved hippocampal insulin resistance and synaptic signalling(Reference Tomé-Carneiro, Carmen Crespo and Burgos-Ramos83) and improved spatial working memory abilities.(Reference Baliyan, Calvo and Piquera84) A subsequent RCT with mildly cognitively impaired older adults (>65 years of age) examined the impact of consuming a milk drink fortified with MFGM (6.8 g PL/100 g) compared with a control milk (0.29 g PL/100 g) over 14 weeks on a range of cognitive tests. This showed that the female, but not male subjects had improved episodic memory after consuming the MFGM enriched drink.(Reference Calvo, Loria Kohen and Díaz-Mardomingo85) The authors suggested that interventions to improve cognition should be started earlier in life despite the greater financial cost.

There is some consensus that the beneficial impact of the MFGM on cognition and potentially dementia is mediated by the polar PL in the membrane.(Reference Schverera, O’Mahonya and O’Riordana79) The most abundant of these are phosphatidylethanolamine (32.0 ± 0.5 % of total PL), phosphatidylcholine (25.1 ± 0.4% of total PL) and plus sphingomyelin (22.6 ± 0.5 % of total PL), a PL of the sphingolipid family.(Reference Thum, Roy and Everett16) All these PLs and others are critical for the functioning of the nervous system and contribute about 60% to the dry weight of the brain.(Reference Ylilauri, Hantunen and Lönnroos77) Whilst overall, human trials are substantially suggestive that a dietary addition of PLs such as found in the MFGM can moderate cognitive impairment, their mode of action is not fully understood. There are however indications that this may involve enhancement of synaptogenesis and neuronal transmission and intracellular signalling together with activity through the gut-microbiota-brain axis.(Reference Ylilauri, Hantunen and Lönnroos77) Indeed, in some animal studies (mice, pigs) with PLs from cow milk have altered the make-up of the microbiota.(Reference Berding, Wang and Monaco86,Reference Norris, Jiang and Ryan87)

Clearly further research is needed to better elucidate the beneficial modes of action of the MFGM and its polar PLs but given the evidence so far and the urgent need to moderate cognitive decline into dementia, the work should have a high priority.

Conclusions

The aim of this review was to highlight some key health and development functionalities of bioactive compounds from milk/dairy foods and their relevance at key life stages. This highlighted the role of gangliosides from the MFGM for neonatal neurodevelopment with indications that MFGM should be included in infant formulae. Also noted was the value of milk proteins for growth stimulation of children by their ability to stimulate hepatic IGF-1. Small animal studies have confirmed that bovine milk exosomes and their contained miRNA are bioavailable and can accumulate in the placenta and embryos, with a mouse study finding that placenta development and embryo survival were both enhanced. It is clearly early days with this subject, but it does seem to have potential health benefits. Aspects of bone health were examined with the critical value of the casein micelle for delivering to the GI tract amounts of Ca, P and Mg more than that which could be supplied in simple solution. The generally neutral or beneficial association of SFA-rich dairy foods with CVD has been puzzling to many but aspects of the dairy food matrix and the hypotensive effect of some peptides released from milk proteins go someway to explain this. The use of GLP-1 receptor agonists for losing body weight and improving glycaemic control has increased substantially in very recent times but it was noted that milk proteins can increase GLP-1 output by the intestinal enteroendocrine L-cells which may reduce the need for GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment in high milk protein consumers. Finally, the beneficial effect of milk bioactive components in the elderly examined the ability of milk proteins, especially whey protein, to stimulate skeletal muscle protein synthesis which provides bone protection and glycaemic control and the role of milk Ca for reducing the risk of CRC. In many ways the potential for the polar phospholipids in the MFGM for improving cognition and potentially reducing the risk of dementia is extremely exciting although it is early days and many more human studies are needed.

Whilst it is true that that some of the activities examined in this review were dependent on nutrients (e.g. Ca in CRC reduction, proteins for GLP-1 stimulation and the provision of MFGM by milk fat), the functionalities they perform would not be recognised simply by the nutrients they provide.

Acknowledgments

This review is based primarily on an invited presentation at the UK and Ireland Nutrition Society annual conference at the University of Loughborough on 1–2 July 2025. I am grateful to the Nutrition Society and members for the invitation and their support for this paper. I am also grateful to Dr Oonagh Markey for proposing this topic for my presentation and this paper.

Author contributions

The author had sole responsibility for preparation of this paper. No aspect of artificial intelligence was used.

Financial support

Whilst there was no specific funding for the writing of this review, but the author’s travel and accommodation costs for conference attendance were paid by the Nutrition Society.

Competing interests

The author has received travel expenses and honoraria in connection with lectures and meetings from the UK Dairy Council (now Dairy UK), the Dutch Dairy Association, the European Dairy Association, the International Dairy Federation, Centre National Interprofessionnel de l’Industrie Laitière and the US Dairy Research Institute.