Conventional-politics approaches, emphasizing party ideology, electoral dynamics, committee membership, campaign donations, and industry clout, exercise a powerful hold over assessments of public policies and their distributional outcomes. Emerging from pluralist and business power perspectives, such accounts see “who gets what and why” as the result of how politics and power shape policies, their implementation, and distributional outcomes. Indeed, this politics → policy → outcome framework pervades our understanding of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), the United States government’s effort to avert mass unemployment during the COVID-19 pandemic by channeling $786 billion over three lending periods to small businesses to keep employees on the payroll. According to Forbes, 71 public corporations received $300 million in loans in the PPP’s first week (Vardi Reference Vardi2020). The New York Times reported that the PPP “allowed big chains like Shake Shack, Potbelly and Ruth’s Chris Steak House to get tens of millions of dollars while many smaller restaurants walked away with nothing” (Yaffe-Bellany Reference Yaffe-Bellany2020). Headlines like “Banks Gave Richest Clients ‘Concierge Treatment’ for Pandemic Aid” (Flitter and Cowley Reference Flitter and Cowley2020) amplified the point, as did scholarly analyses (Chernenko and Scharfstein Reference Chernenko and Scharfstein2022; Fairlie Reference Fairlie2020; Grotto, Mider, and Sam Reference Grotto, Mider and Sam2020; Howell et al. Reference Howell, Kuchler, Snitkof, Stroebel and Wong2021; Sanchez-Moyano Reference Sanchez-Moyano2021; Wong, Ong, and González Reference Wong, Ong and González2020). PPP loans flowed to those with influence and access—banks’ favored clients, large and often still profitable employers, affluent and white areas, districts with influential representatives—rather than small businesses in the hardest-hit Black and brown communities.

Yet contrary to prior studies of the PPP, we find that conventional-politics factors were strikingly uncorrelated with these outcomes, revealing limits to such approaches to this case. Instead, we find that an institutional politics or politics-in-time (IP-PIT) approach better explains the PPP and its trajectories. IP-PIT revises the causal sequence by emphasizing how institutions and policies generate politics, distributional outcomes, and feedback loops, suggesting a policies → politics/outcomes → policies sequence (Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Reference Pierson2004; Sorelle Reference Sorelle2023) with distinct periods. Crises, like a pandemic, spark critical junctures and suspend conventional politics, creating opportunities for policy innovations. Once in place, “policies create new politics” (Campbell Reference Campbell2012; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2019; Jacobs and Weaver Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1935). They endogenously produce processes that set systems on a path, whether by generating new political interests (Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1996), (de)mobilizing constituencies (Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Sorelle Reference Sorelle2023; Thurston Reference Thurston2015), inducing new organizations (North Reference North1990), or framing calculation and debate (Dobbin Reference Dobbin1994).

We engage these approaches via a mixed-methods analysis of the PPP and two new datasets. We anchor our study in a qualitative process-tracing analysis of temporal variation in policy architectures, politics, policy revisions, and shifting access to loans within and across the program’s three periods. This analysis reveals a suspension of business-as-usual political routines at the beginning of the program—a critical juncture that explains the PPP’s scale, quick passage, and initial core architectures. It reveals further that the PPP evolved dynamically over its three lending periods, as policy feedbacks altered policies and outcomes. Moreover, rather than trigger positive feedback in which programs foster their own supporting coalitions, the PPP sparked negative feedback, political backlash, and policy revisions that transformed the program from one that overwhelmingly favored large businesses, affluent areas, and white communities into one that delivered millions of loans to smaller businesses, especially in poorer and hard-hit Black and brown communities.

We then engage each approach further via quantitative analyses of program lending across congressional districts and periods using data on the entire corpus of PPP loans. We review and replicate prior quantitative analyses of PPP lending dominated by conventional-politics approaches and find that such models poorly explain loan distributions. Instead, we consider and confirm IP-PIT claims that what impacts outcomes depends on timing in a developmental sequence. The effects on loans of business size and socioeconomic factors change over the PPP’s three periods as its politics and policies evolve.

Through these analyses, we use one of the US government’s largest economic interventions since the New Deal as a deviant case (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) to advance research and debate over the dynamics and outcomes of US policy making during crises. This links to general debates about the American political economy, including the embeddedness of race and organized interests, spatial variation in distributional outcomes, and the time-dependent dynamics of coalition formation (Hacker et al. Reference Hacker, Hertel-Fernandez, Pierson and Thelen2022). Ours is the first study of the PPP to conduct a mixed-methods analysis of loans across congressional districts or to use conventional and institutional approaches to address its politics, policy, and outcomes. This highlights important and likely general limits on the capacities of conventional politics to explain policy making during crises. It also lets us show that IP-PIT arguments about critical junctures, punctuation, and pathways apply not just to epochal institutional change like the welfare state or private insurer-based healthcare, but also to temporary crisis management episodes, which may or may not reset the system beyond the duration of the intervention. Furthermore, our study advances specific arguments within IP-PIT approaches. We document varieties of critical junctures, contribute arguments about what might shape policy or institutional innovation in those moments, and use the PPP to identify conditions under which systems are “their own grave diggers,” fueling negative-transformative rather than positive-reproductive feedback.

The PPP and Loan Rates across Congressional Districts

The PPP was established through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act on March 27, 2020. It allocated $349 billion for guaranteed and ultimately forgivable loans to small businesses to keep their employees on the payroll. Lawmakers intended the PPP as a one-off effort to “flatten the curve.” Yet they refunded the program on April 24 via the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, allocating an additional $320 billion, and again on December 27, via the Consolidated Appropriations Act, adding another $284 billion.Footnote 1 These acts produced a program marked by three periods of lending from April 2020 through May 2021, during which over 11.3 million loans totaling $786 billion were issued.Footnote 2

As is relatively common in US public policy, the PPP was structured as a public–private collaboration (Bartik et al. Reference Bartik, Cullen, Glaeser, Luca, Stanton and Sunderam2020) that worked through private lenders to achieve policy goals (Prasad Reference Prasad2012; Quinn Reference Quinn2019). The CARES Act crafted the PPP around the 7(a) loan guarantee program offered by the Small Business Administration (SBA). It assigned oversight and rulemaking to the SBA, supported by the US Treasury, delegated the underwriting and delivering of funds to the SBA’s network of lenders, and relied on 7(a)’s bureaucratic machinery and electronic transaction (ETran) portal to authorize lenders and process loans. Businesses needing support had to find and work through an authorized lender to access funds.

The distribution of PPP loans varied substantially over time and across congressional districts. Lenders issued 1.61 million loans in period 1 (April 3–16, 2020); over double that in period 2 (April 27–August 8, 2020; 3.48 million); and nearly double that again in period 3 (January 11–May 31, 2021; 6.28 million). The pattern drove cumulative loan rates (the average number of loans divided by total establishments and self-employed) from 0.093 in period 1 to 0.283 and 0.611 in periods 2 and 3. By the end of the program, 45.4% of businesses had received a loan (see online appendix A).

Moreover, congressional districts shared unequally in this largesse. PPP loans first flowed to larger, often profitable recipients in more affluent and white areas less hit by the pandemic rather than small businesses in the hardest-hit and often poorer Black and brown communities (Birdthistle and Silver Reference Birdthistle and Silver2021; Borawski and Schweitzer Reference Borawski and Schweitzer2021; Chernenko and Scharfstein Reference Chernenko and Scharfstein2022; Granja et al. Reference Granja, Makridis, Yannelis and Zwick2021; Howell et al. Reference Howell, Kuchler, Snitkof, Stroebel and Wong2021; Liu and Parilla Reference Liu and Parilla2020; Sanchez-Moyano Reference Sanchez-Moyano2021). In period 1, districts in Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Nebraska, Vermont, and Wyoming topped the list with loan rates between 0.14 and 0.20, exceeding by five- to almost tenfold loan rates in the most devastated poorer and minority districts in Arizona, California, Florida, or New York. Distributions shifted in periods 2 and 3, with rates increasing dramatically in some of the hardest-hit districts previously left out. Cumulative rates rose to 0.30 or more in period 2 in Atlanta, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, New York City, and southern Florida. By the end of period 3 many of these places recorded loan rates up to 0.70 or more. However, striking differences remained, with rates in the most subscribed districts in Florida, Georgia, and Illinois up to three times higher than rates in some California, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Texas districts, which ranged from 0.32 to 0.42. Our analyses explain the processes driving the evolution of these loan allocations across time and place.

From Conventional to Institutional Politics and Politics-in-Time

Academic research on the PPP builds on strong empirical foundations when it takes understanding the program’s unequal and shifting distributions and failures to target the hardest-hit areas as its core analytical agenda. Moreover, in pursuing that agenda, researchers lean on conventional or business-as-usual politics arguments about party affiliations, electoral calculation, and the like to explain PPP distributions and departures from policy goals, drawing selectively on a larger and well-developed scholarly tradition in policy studies. We leave aside the wider literature on conventional politics as beyond our scope, and focus instead on scholarly work on the PPP, which nicely covers key conventional-politics dynamics.

Work on the PPP credits unequal loan allocations and program failures to three sets of factors: (1) electoral dynamics, including party politics, party ideology, and politicians directing funds to battleground areas or rewarding their base (Birdthistle and Silver Reference Birdthistle and Silver2021; Duchin and Hackney Reference Duchin and Hackney2021; Ha Reference Ha2023); (2) congressional committee membership or chairmanship and the influence and access it affords for selected constituents or districts (Berger, Karakaplan, and Roman Reference Berger, Karakaplan and Roman2023; Ha Reference Ha2023); and (3) the power and lobbying of wealthy constituents, affluent areas, or larger employers’ banks (Berger, Karakaplan, and Roman Reference Berger, Karakaplan and Roman2023; Duchin and Hackney Reference Duchin and Hackney2021; Igan et al. Reference Igan, Lambert and Mishra2021). Analyses in this body of work span geographies and generate sometimes divergent results. However, they share the view that these conventional politics drove the distribution of loans in the PPP.

Highlighting political ideology, Berger, Karakaplan, and Roman (Reference Berger, Karakaplan and Roman2023) find that greater proportions of businesses received loans in conservative and centrist counties with high concentrations of lenders and where greater percentages of businesses lobby the federal government. Other scholars directly target party and competitive dynamics, and link distributions in the first two periods to states that voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential election (Birdthistle and Silver Reference Birdthistle and Silver2021); to battleground states, or Republican-leaning states, districts, or sectors (Duchin and Hackney Reference Duchin and Hackney2021); and to efforts by members of Congress or the president to enhance their electoral position. Sabasteanski, Brooks, and Chandler’s (Reference Sabasteanski, Brooks and Chandler2021) analysis points in the opposite direction, finding that Republican districts, especially those with more African American constituents, received less funding than Democratic ones, which calls into question links between party and loans. Yet Ha’s (Reference Ha2023) analysis of the third period finds that Democratic districts and pro-Biden and Democratic counties, but not swing counties, received more PPP funding under the Biden presidency, confirming party effects rooted in presidential particularism and the party in power.

PPP research also emphasizes how membership of powerful congressional committees lets representatives direct benefits to their constituencies, although evidence here is mixed. Businesses in districts with members on the House Committee on Small Business received more loans than otherwise in one study (Berger, Karakaplan, and Roman Reference Berger, Karakaplan and Roman2023), but committee chairmanship had no statistically significant impact on allocations in another (Ha Reference Ha2023). In contrast, business-lobbying impacts on PPP loans seem clearer. Businesses (and banks) that lobbied received (or issued) more loans than those that did not, with greater effect in industries that accounted for greater shares of campaign dollars (Barrick, Olson, and Rajgopal Reference Barrick, Olson and Rajgopal2021; Berger, Karakaplan, and Roman Reference Berger, Karakaplan and Roman2023; Birdthistle and Silver Reference Birdthistle and Silver2021; Igan et. al Reference Igan, Lambert and Mishra2021; Sabasteanski, Brooks, and Chandler Reference Sabasteanski, Brooks and Chandler2021).

These studies develop our conceptual repertoire for understanding PPP allocations, yet assume that business-as-usual politics carried over to a policy that emerged in a crisis that profoundly disrupted normal political routines and calculations. They also pay little attention to how policy architectures generate their own trajectories and politics, shifting political calculations, distributional outcomes, and even what shapes those outcomes over time as contexts evolve. This would require in-depth qualitative analyses of the PPP’s policy making and implementation, and additional theoretical guidance, for which we turn to an alternative IP-PIT approach.

Emerging from historical institutionalism in comparative and American politics (Brady Reference Brady1991; Orren and Skowronek Reference Orren, Skowronek, Shapiro and Hardin1996; Thelen and Steinmo Reference Thelen, Steinmo, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992), IP-PIT revises conventional analyses of politics → policy → outcome by theorizing policies and outcomes as developmental sequences marked by distinct periods and combinations of exogenous and endogenous forces. Sequences typically begin with a critical juncture in which an external shock or crisis “punctuates” institutional equilibria. This sparks conflict and innovations that point the system in new directions, followed by a reset in which new policies or institutions induce new politics and other feedback processes that set the system on a new trajectory (Campbell Reference Campbell2012; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2019; Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Pierson Reference Pierson1993; Reference Pierson2004; Sorensen Reference Sorensen2023). Punctuations, junctures, and innovations can flow from technological change (Tushman and Anderson Reference Tushman and Anderson1986), wars (Ikenberry Reference Ikenberry2019), depressions (Campbell and Lindberg Reference Campbell and Lindberg1990; Fligstein Reference Fligstein1990; Skowronek Reference Skowronek1982), environmental disasters (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1999), or pandemics (Rao and Greve Reference Rao and Greve2018). Once in place, new institutions become causal forces in their own right. They induce feedback—politics, investments, and adaptations—that fixes the system and its participants on a new trajectory leading to entrenchment and persistence (Arthur Reference Arthur1989; Sorensen Reference Sorensen2023; Thurston Reference Thurston2015). Indeed, feedback and increasing returns can shift what factors shape outcomes over time by rendering them increasingly dependent on the structure of the evolving path and increasingly impervious to functional economic requirements, conventional political influence, or interest-group demands (Pierson Reference Pierson2000).

While crafted to explain epochal and long-term transformations in institutions or enduring shifts in macropolicy regimes like the welfare state or private insurance-based healthcare systems, IP-PIT and its core elements can also apply more specifically to policy making in crises, like the PPP. These cases involve immediate and temporary solutions that often do not yield long-term resets of economic, political, or policy systems.

Consider first critical junctures: IP-PIT accounts view these as moments of profound disruption. They upend established political and economic processes and settlements, call into question the legitimacy of existing arrangements, provide leverage for challengers to advance alternative schemes, and induce systemic struggles over the basic rules of the game (Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Mahoney and Thelen2015; Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007, 343; Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012; Schneiberg Reference Schneiberg2005; Sine and David Reference Sine and David2003; Sorensen Reference Sorensen2023; Thurston Reference Thurston2015). However, crises and wholesale disruptions, like the COVID-19 pandemic or the 2008 financial crisis, can suspend conventional political dynamics and create windows for policy innovation without wholesale struggles over the system. As Capoccia and Kelemen (Reference Capoccia and Kelemen2007) point out, short time spans in critical junctures come with loosened structural constraints, which may be the case for two reasons. First, crises may involve “Lehman moments,” like the 2008 collapse of the investment-banking giant Lehman Brothers that triggered the global financial crisis. Such moments pose systemic threats. Under profound uncertainties, they require immediate interventions to prevent large-scale, cascading losses, and compel policy makers to suspend or bypass standard routines for emergency processes. In addition, crises might also be limited in duration, or framed as such by policy makers, supporting policies advanced as short-term and temporary measures to be abandoned or revisited. In these scenarios, uncertainties and the costs of insufficient action are understood to be so high that they trump all other political preferences, reducing policy makers’ incentives and safeguards to resist emergency policy making. Moreover, with an understanding that policy architectures are temporary solutions, policy makers may accept measures, including even quite substantial interventions, that they would not agree to under normal circumstances, and they may have little incentive to pursue broader, more systematic change. To the contrary, as behavioral scholars suggest, decision makers, facing high-stakes conditions under great uncertainty, are far more likely to focus first on what is already “at hand,” gravitating toward “off-the-shelf” solutions with at least partly known contours and potentially predictable impacts (Cohen, March, and Olsen Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972; Kingdon Reference Kingdon2011; Stinchcombe Reference Stinchcombe1990).

Second, IP-PIT feedback mechanisms also apply to policy making during crises. Once in place, new policies or institutions like the PPP, even when crafted as temporary, carry independent causal weight. Their design imposes constraints and incentives for action, activating political responses and other processes that fix the system on a path or trajectory (Arthur Reference Arthur1989; Edelman, Uggen, and Erlanger Reference Edelman, Uggen and Erlanger1999; Pierson Reference Pierson2004). Path-dependence scholars initially focused on endogenous positive feedback processes in which policies or institutions bias subsequent development in reproductive directions. New arrangements entail setup costs, investments, and adaptation that make switching paths increasingly costly, especially once actors have learned to navigate the new institutional landscape (Campbell Reference Campbell2012; North Reference North1990; Pierson Reference Pierson2004). Institutions can also induce their own politico-cultural dynamics and support, whether by (de)mobilizing constituencies (Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Sorelle Reference Sorelle2023; Thurston Reference Thurston2015), creating new vested interests (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2019; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1996), or prompting investments in new mental maps or conceptions of governance that frame problem solving and debate (Dobbin Reference Dobbin1994; Edelman, Uggen, and Erlanger Reference Edelman, Uggen and Erlanger1999; Fligstein Reference Fligstein1990; Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012). These adaptive dynamics can lock-in new policies or institutions, rendering them and their distributional outcomes less dependent on starting conditions and progressively more dependent on policy architectures and the calculations, politics, and organizations they induce.

Yet they can also activate negative feedback processes that undermine their basic operation and foster trajectories of reform and change (Daugbjerg and Kay Reference Daugbjerg and Kay2020; Jacobs and Weaver Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Patashnik and Zelizer Reference Patashnik and Zelizer2013; Schneiberg Reference Schneiberg2005; Thurston Reference Thurston2015; Weaver Reference Weaver2010). Institutional resets produce winners and losers, including new actors with new logics and ideas and an interest in challenging the status quo (Clemens Reference Clemens1997; Leblebici et al. Reference Leblebici, Salancik, Copay and King1991; Stryker Reference Stryker, Stryker, Owens and White2000; Weaver Reference Weaver2010). Resets to address one set of problems can create new ones (Hollingsworth and Streeck Reference Hollingsworth, Streeck, Hollingsworth, Schmitter and Streeck1994). They induce patterns of competition and strategic behavior that disconnect policies and stated outcomes, generate accumulating costs, and alter the payoffs of existing policies relative to alternatives. This, in turn, may induce defections from existing coalitions and create opportunities for challengers to advance new solutions (Leblebici et al. Reference Leblebici, Salancik, Copay and King1991; Schneiberg Reference Schneiberg2005). Dysfunctionalities can trigger public outcry, allowing defectors to leverage saliency. Ultimately, this might lead to legitimacy crises. Such potent solvents for “iron triangles” and entrenched interests (Bovens and Hart Reference Bovens and T Hart1996; Wallner Reference Wallner2008) let excluded actors and entrepreneurs build public support for reform. In short, resets can trigger political backlash and coalitions sufficiently powerful to block a policy’s operations, roll back implementation, and push for change (Patashnik and Zelizer Reference Patashnik and Zelizer2013; Weaver Reference Weaver2010). Additionally, preexisting heterogeneity in “what’s on the path” in terms of institutional logics, alternative ideas, or organizational systems can amplify possibilities for negative feedback by providing actors with broader perspectives on possibilities and organizational vehicles to redirect resources (Daugbjerg and Kay Reference Daugbjerg and Kay2020; Schneiberg Reference Schneiberg2007; Weaver Reference Weaver2010; see also Stryker Reference Stryker, Stryker, Owens and White2000; Thornton, Occasio, and Lounsbury Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012).

In sum, the preceding suggests several expectations for the PPP. First, its lending across congressional districts will have been less a product of conventional politics than outcomes of a critical juncture and responses by policy makers to the uncertainties and pressing demands associated with a combined economic and public health crisis. Second, the program’s distributional outcomes and evolution will have emanated from its architectures—from the feedback processes that locked-in a trajectory of policies and reforms that sustained and induced new organizational compositions and resource flows. And finally, the effects of politics and other characteristics on loan flows will have depended on timing in the PPP’s developmental sequence. They will have shifted as the program evolved away from its starting point, became a causal factor in its own right, and fueled its own politics and path dependencies.

Methods and Data

We engage these approaches via a mixed-methods design, combining process tracing with statistical modeling. At root, our study analyzes temporal variations and linkages between politics and outcomes within and across the PPP’s three periods. We also supplement this with analyses of PPP loan flows across congressional districts. We mirror our process-analytic approach of tracking politics, policy revisions, and shifts in loan flows across periods as much as possible by modeling time-varying effects of key factors on loan distributions across program periods. In both strategies, we aim not to assess conventional-politics or IP-PIT approaches generally, but rather to use the PPP as a deviant case (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) to consider their relevance to policy making during crises and suggest avenues for future research.

Our qualitative analysis focuses on the causal mechanism (Glennan Reference Glennan1996) linking the PPP’s policy, politics, and distributional outcomes. Following “theory-building process tracing” (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2013), we do not seek to test a given boilerplate mechanism but instead strive to mobilize IP-PIT arguments for opening the PPP’s black box of policy revisions and shifting loan flows. We engage counterarguments, including those grounded in conventional politics, natural progression, or protest dynamics, to probe the validity of our mechanism and its theoretical and empirical “uniqueness” (Beach Reference Beach2016). Finally, we reach beyond the confines of within-case inference in the PPP and reflect on limitations and generalizability of IP-PIT-inspired applications to policy making during crises as components of theory building. We begin with the program’s initial design and distribution, and then follow program changes and their impacts over the three program periods. At each step, we work from policy design to politics and outcomes and back, carefully reconstructing the timeline that links salience, mobilization, revisions, and new loan flows. This work detects causal process observations as elements or building blocks of mechanisms and context (Collier, Brady, and Seawright Reference Collier, Brady, Seawright, Brady and Collier2010), letting us assess both conventional political processes and IP-PIT arguments about path dependence, endogenous dynamics, and feedback.

Qualitative data come from 82 semistructured interviews conducted from September 2022 through December 2023. Respondents include borrowers and lenders (41); national and local advocacy groups (18); lender associations (eight); congressional staff (seven); and local political leaders, PPP experts, and SBA officials (eight).Footnote 3 We also analyze the entire body of 224 congressional hearings on the PPP between April 23, 2020, and June 30, 2021. We searched the universe of news publications in Factiva’s database of 91 top news and business sources in the US and coded and counted articles, using “paycheck protection” and a range of search terms for inclusivity and bias to measure the media’s evolving attention. Finally, we closely read key documents, including (1) reports by the Government Accountability Office, Congressional Research Service, and the Office of Inspector General; (2) survey reports of lender organizations; (3) advocacy briefings and letters; (4) academic scholarship; and (5) periodical accounts, particularly from the New York Times and Washington Post.

We supplement our qualitative analysis of within-unit variation over time (Gerring Reference Gerring2004) with quantitative analyses of causal effects on the distribution of PPP loans. We fit cluster-robust random-effects models on the impact of standard political factors on PPP loans, incorporating the corpus of prior quantitative work on the PPP. We extend this strategy to address our IP-PIT-based qualitative findings via models that let key effects on loan flows vary across periods as the program’s politics and policy architectures evolve.

For these analyses, we built a dataset of PPP loans using SBA loan-level data for the nearly 11.4 million PPP loans made from April 3, 2020, to May 31, 2021. We exclude loans flagged as likely fraudulent by Griffin, Kruger, and Mahajan (Reference Griffin, Kruger and Mahajan2023), leaving 10.4 million. We aggregate loan numbers and value to congressional districts for each lending period, creating a panel dataset and our main dependent variable: district loan counts in each period normalized by the sum of establishments and unincorporated, full-time self-employed individuals. We supplement this with (1) descriptive analyses using daily counts of loans to match policy reform clusters to loan flows, and (2) models that use weekly district loan counts and reparameterize time by compartmentalizing by clusters of reforms rather than lending rounds.

We model conventional politics mainly using the party affiliation of representatives in the 116th and 117th Congresses; electoral competitiveness of House races using the absolute value of the Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voting Index (Cook Political Report n.d.); and membership on committees involved in PPP legislation (House Appropriations, House Small Business, House Ways and Means, and Senate Small Business). For business power, we include total inside-the-district campaign donations to winning House candidates in the two election cycles spanning the PPP’s arc using data from OpenSecrets.org (Center for Responsive Politics n.d.) and the share of large businesses with more than five hundred employees calculated from County Business Patterns data (US Census Bureau 2024). For IP-PIT arguments, we include variables for poverty rates, ethnoracial compositions, and period interaction terms to capture time-varying effects of these key covariates suggested by our qualitative findings.

In all models we control for district population, for COVID-19 severity using Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies data on the number of positive cases per thousand residents as of July 13, 2020 (Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies 2021), and for economic vulnerability to the pandemic using the share of “hardest-hit businesses” from “high contact” industries (accommodation and food, arts and entertainment, wholesale and retail) calculated from County Business Patterns data (US Census Bureau 2024). We include state fixed effects, density fixed effects from CityLab’s District Density Index (Montgomery Reference Montgomery2018), a six-step scale from “purely rural” to “purely urban,” and conduct extensive robustness checks (online appendices B and E–F). Quantitative data used in the analysis is available through Harvard’s Dataverse (Schwan, Schneiberg, and Cassell Reference Schwan, Schneiberg and Cassell2025).

Qualitative Results

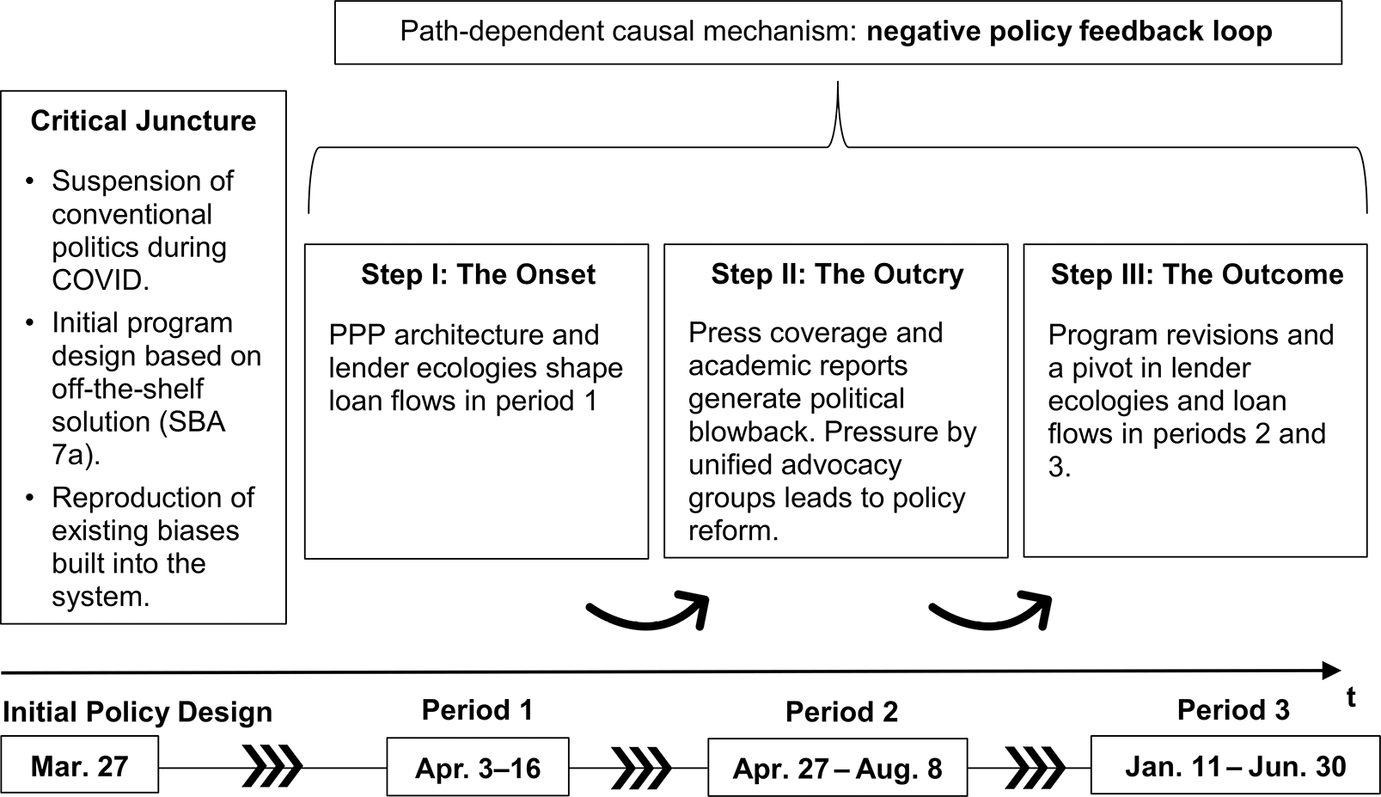

Process tracing identified a three-step causal mechanism linked to a critical juncture. We traced the PPP’s initial design backward—to a critical juncture at which policy makers crafted an “off-the-shelf” solution using the banking system—and forward—to how that policy architecture produced period 1’s lopsided loan flows. Working forward over periods 2 and 3, we traced a sequence of events from the PPP’s initial architecture to its evolution and shifting distributions, as unequal loan flows generated negative feedback loops and a stream of policy revisions reconfiguring the lender system and loan flows. We find endogenous yet transformative dynamics in which policy generated politics and reform. Figure 1 summarizes our findings. The process began with the pandemic and PPP rollout and design (critical juncture). That design induced unequal loan distributions (onset), resulting in criticism by media outlets and advocacy groups (outcry) and policy revisions that induced more inclusive lending in periods 2 and 3 (outcome).

Figure 1 The PPP’s Origin and Its Mechanism-Based Evolution

Critical Juncture and Genesis

Interviewees highlight the unusual circumstances leading to the PPP and the central role played by the Senate at the outset, in particular by Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL), Susan Collins (R-ME), and Ben Cardin (D-MD). First, policy makers in March 2020 faced unprecedented uncertainty about COVID-19 and its course, profound anxiety about the economic impacts of the pandemic and closures, and an urgent need to act immediately. As a Democratic staffer explained, Congress was “trying to legislate in one of the most uncertain environments we’ve experienced as a country, at least in a generation.”Footnote 4 Fears of massive unemployment and upheaval were at the top of policy makers’ minds, as an SBA official related:

Data in early March came out. We went from 4.1 or 3.9% unemployment to 14% by the end of March, with credible projections of going up to 32%. Really smart people were super concerned about a Great Depression. If we didn’t do something, the global economy would fall off the cliff.Footnote 5

Officials understood they had arrived at a critical juncture. The “cash flow and business reality for small businesses, which comprise two-thirds of the private sector employment in the US, was really scary. We knew at the time that mass layoffs would be detrimental to our society,” one explained, risking “a total breakdown of society when people are not connected to employment.”Footnote 6 From this emerged a frame in which officials cast the problem as needing to act fast to “flatten the curve” of new infections. They conceived the PPP as a one-shot intervention until businesses reopened and people returned to work.Footnote 7

Second, the pandemic and lockdowns profoundly disrupted the policy-making process. Officials crafted policy while socially and politically isolated, and sometimes fell ill. No hearings, public forums, or press conferences were held at this juncture. “It was chaotic,” a Republican staffer noted.Footnote 8 With the Capitol on lockdown, virtually no one was there except for legislators and their staff, huddled together in rooms, another staffer elaborated. This was “not a normal legislative process where you have a committee hearing, and people speak, and you see who is opposed to it and who’s for it, and then it goes through.”Footnote 9 “We were trying to social distance doing this,” explained an SBA official. “[I]t was like trying to run a war room, and you’re in separate rooms.”Footnote 10

Under intense time pressure, officials reorganized for a speedy result. Meetings for the PPP were confined to a select group of mostly Republican lawmakers; members and staffers worked virtually or in small groups; committee chairs met weekly with then Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) to coordinate; roles were blurred. As a staffer put it, “[y]ou had senators playing what in ordinary times would be staff function … because we didn’t have the time.”Footnote 11 Further, policy making in isolation upended lobbying:

With schools closing, people shutting down … I was getting more texts from people with questions than an organized effort from a trade association or an industry group or lobbyists or whatever. They just didn’t move that quickly.Footnote 12

“We talked with the lenders after we came up with the idea,” another staffer related. “We knew what we wanted to do, and the question [to banks] was, Can you handle it?”Footnote 13 Bankers experienced “a chaotic process,”Footnote 14 but understood, as another staffer explained, that

[i]f you’re going to design something quick, quick, quick, you’re going to keep the room pretty small. I get that speed. … [T]he administration worked quickly and quietly, but the stakeholders were not involved.Footnote 15

Through this process, the Senate assembled a program that went from idea to signed legislation in under a month, an extraordinary achievement impossible via conventional political processes. It was “fast and furious,” a small-business association representative quipped.Footnote 16 “[I]n late February,” a policy advocate related in reflecting on the entire CARES package,

we were … talking about … hundreds of millions of dollars in relief, hundreds of millions. Then a week later, it was half a trillion. And that was considered insane. … Could we even fathom this? And then two weeks later, we were not blinking an eye and suggesting three trillion dollars go out the door. It was very fast, very, very fast.Footnote 17

Third, these policy-making conditions led neither to prolonged horse trading nor partisan stalemate or struggles over the rules of the game, but rather to selecting a scalable, short-term, off-the-shelf, and ready-to-go solution based on existing policies and institutions. Senator Marco Rubio, the SBA and Entrepreneurship Committee chair, took the lead. Rubio proposed an expanded SBA 7(a) program in group and leadership meetings. He had previously crafted an industrial policy plan to scale up SBA loan programs to bolster US innovation capacity to compete with China. He used that plan to enroll Senators Susan Collins and Ben Cardin and House Small Business Chair Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) into the push for a 7(a) option. A Rubio committee staffer explained,

[W]e were just using the levers available to us. … [W]e were building PPP off of the existing 7(a) program … making direct amendments … because our goal was both as a matter of politics for getting the thing done and as a matter of policy for having something that could go to work quickly. Our goal was to reformat the existing program by essentially changing the numbers in the existing 7(a) program, changing the guarantee … changing uses. … You had this existing base of about eight hundred SBA lenders who, on day one, the thought was you could just change via keystrokes … what they were doing with their existing client bases.Footnote 18

Senator Rubio and others recognized that retrofitting a long-standing program addressed pressing concerns of urgency and scale. SBA and 7(a) were known and trusted, mitigating uncertainty. The program also came with a network of existing, vetted, and connected lenders through which funds could be immediately disbursed, “a coast-to-coast delivery system.”Footnote 19 A key insider said this was a decisive advantage for senators and the administration:

There are banks in every city in America, just about every small town in America. It was the best delivery mechanism that we had at the time to get money into the hands of businesses quickly so that they would hold on to their employees so that the government could pay these employees during this period of closure.Footnote 20

Using banks with their established assessment and distribution network, this public–private collaboration bypassed practical concerns about limited administrative capacities to vet millions of transactions, while assuaging Republican opposition to “free money” and expanding federal powers. “Treasury trusts banks,” the head of a lender association noted, “not this boogeyman that is the IRS.”Footnote 21 Rubio’s proposal thus triumphed quickly over proposals to provide grants to small businesses through the IRS or expand the SBA’s Economic Injury Disaster Loan relief program of direct lending and grants.

Democrats worried that retrofitting SBA 7(a) and building banks into the PPP’s core would reproduce preexisting biases and discriminatory practices. Led by Senator Ben Cardin, Democrats pushed to include a “sense of the Senate” resolution on page 30 of the CARES Act calling for the administrator to issue guidance to lenders to prioritize underserved markets and businesses owned by women and “socially and economically disadvantaged individuals.” Yet even among community development financial institutions (CDFIs) committed to those aims, advocates appreciated the pressures to rely on 7(a) banks. As an advocacy representative noted,

if you’re trying to move a lot of money quickly … an organization that has scale is going to be able to do that. … Bank of America is going to be able to move faster than a community-based lender.”Footnote 22

Lawmakers walked a tightrope, forging a program of unprecedented scale built on existing institutions and networks at a critical juncture and under extraordinary time constraints.

Launched on April 3, 2020, this architecture set into motion a sequence, documented in figure 1, that shaped and reshaped loan flows over time. In this sequence, policy architectures and outcomes induced, rather than merely reflected, organization and politics. In period 1, the PPP’s basic design prioritized subsets of lenders and borrowers, yielding a one-sided distribution. This in turn activated negative feedback dynamics, fueling a media storm, political backlash led by newly formed group the Page 30 Coalition, and through these, policy revisions that reconfigured the lender ecologies and loan flows.

The Onset

Respondents emphasized how the PPP’s design ensured loan flows in period 1 went mainly to larger, more profitable employers operating in less hard-hit, more affluent, and predominantly white communities. First, using SBA 7(a) placed the least inclusive but already approved mainstream banks first in the queue (large bank holding corporations, larger commercial banks, community banks) while closing out lenders with track records for reaching borrowers in poor and minority communities (CDFIs and financial technology services [fintechs]).Footnote 23 The SBA wrote rules to allow CDFIs and other nondepository lenders to participate. However, it did so only after period 1 was underway and required at least $50 million in prior-year small-business loans, which “pushed out a lot of smaller, but high-performing CDFIs that could have made a real contribution in their communities,” according to two CDFI observers.Footnote 24 Even eligible newcomers struggled to negotiate the SBA approval process, protocols, and portals, delaying entry. Noninclusive lenders issued 93% of period 1 loans.

Second, the program granted lenders discretion to prioritize applicants, leaving in place mainstream banks’ preexisting relationships with clients and their long history of disconnect, discrimination, and mistrust with poor and minority communities. This yielded “predictable results.” “Many banks decided to handle only existing clients,” one bank’s chief loan officer reported. “Wealthy existing clients,” its CEO added. “And they did not open those to noncustomers.”Footnote 25 Banks had an interest in keeping existing clients solvent and used their ties to reach out to them to share information and access the PPP. Borrowers with prior relationships caught banks’ attention. Additionally, “know your customer” rules, 7(a) contingent guarantees, and the PPP’s borrower self-certification made banks anxious and unwilling to lend to unknown clients. As an SBA lender explained, banks eventually knew that PPP loans were

100% forgivable and 100% protected. But that was not everyone’s first blush of how this thing was going to roll out. The first loans … were by lenders to folks that they thought they could count on no matter how this ended up unraveling.Footnote 26

Furthermore, the program design reinforced the deeply ingrained economic calculus that small loans are too costly to write. According to one observer,

banks said, “You know what, your loan is too small for us. We can’t justify spending time, just go to the credit union next door, they will take care of you.” … Because look, for banks even with the fee structure, it didn’t make sense.Footnote 27

This militated against small, often informal or cash-based operations in minority or poor areas that needed small loans and “a lot of hand holding and explaining [and] trust building”Footnote 28 to connect and become eligible. “[T]he business model … is very expensive,” a CDFI officer explained, “because this is a very high-touch model [and] sometimes you have to actually go back to basics of bookkeeping [and] tax returns.”Footnote 29

Third, lawmakers, at the urging of Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin, launched the PPP as a program for employer organizations without rules or forms for solo operators or Schedule C filers. When the SBA issued rules for such filers, it required using “net profits” for loan eligibility and amounts, disqualifying businesses with depreciation and a loss for the prior year. This excluded single-person operations that predominated in distressed and minority communities. One city’s Black Chamber of Commerce president summarized these effects:

The first wave certainly was pretty much inaccessible to most of our Black-owned businesses. … One, they did not have established banking relationships where their bankers could call and say, “You need to apply for this.” Two, they did not have the financials in place that qualified them for such. Third, most Black-owned or small businesses are solo entrepreneurs. So, they did not have the employees that would allow them to take advantage of the PPP.Footnote 30

Finally, respondents highlighted how quickly the program exhausted its first allocation and how the first-come, first-served design sparked a competitive run on funds that exacerbated inequalities. When “they opened up PPP, it was a stampede.”Footnote 31 “[W]e were just rushing, rushing, rushing, rushing in 2020, right?” a loan officer recalled, “’[c]ause everybody was just lending from the same or borrowing from the same pool.”Footnote 32 Lenders serving underresourced areas could not get into the queue as large banks deluged the portal with their automated systems. In “period 1, we got locked out … the money was used up in eight days, and we only managed to get nine applications in,” a CDFI loan officer explained.Footnote 33

In short, PPP’s initial design induced a deeply skewed distribution of lenders and loan flows, independently of conventional political dynamics rooted in party affiliations, electoral competition, or lobbying.

The Outcry

The initial allocation of funds sparked a surge of media exposés and political blowback. It also facilitated the formation of the Page 30 Coalition in April 2020, a broad reform group named after the CARES Act page containing the “sense of the Senate” resolution, which comprised at its peak nearly a hundred associations, advocacy organizations, and lenders (see online appendix C). At the forefront of PPP criticism, the Page 30 Coalition sought to raise the salience of the program, direct attention to its failures, and exploit the potential for reform. “Black firms are being shut down,” said one respondent,Footnote 34 echoing observations from multiple quarters (e.g., Flitter and Cowley Reference Flitter and Cowley2020; Mills and Battisto Reference Mills and Battisto2020) that were presented in a much-cited report that found four of 10 Black businesses had gone under due to COVID-19 (Fairlie Reference Fairlie2020). The SBA “knew what had to be done,” the CEO of a large CDFI expressed, “but CDFIs were not lending at that time. … We could have, but there were no regulations even there.”Footnote 35 An association officer noted that this fueled “blowback to the mainstream banks.”Footnote 36

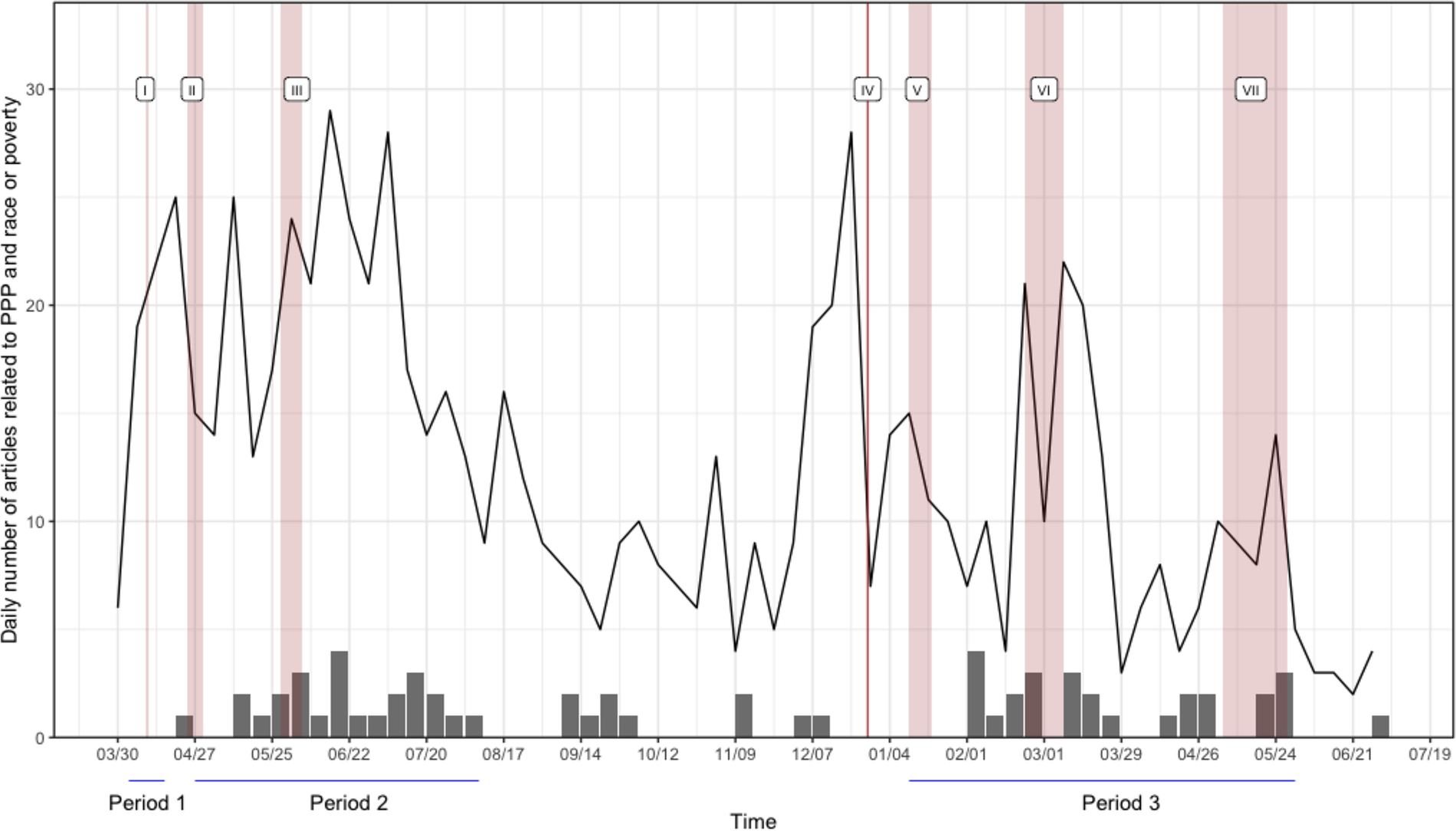

News accounts underwrote outrage and mobilization. Studies and government reports filled empirical gaps (Chetty et al. Reference Chetty, Friedman and Stepner2020; Fairlie Reference Fairlie2020; Government Accountability Office 2021; Office of Inspector General 2020). Figure 2 plots weekly counts of articles linking the PPP to minority businesses and racial disparity (line chart) along with weekly counts of congressional hearings (bar chart) and bands of policy reforms (shaded areas, detailed in table 1 below).

Figure 2 Media Attention and Congressional Hearings, April 2020–July 2021

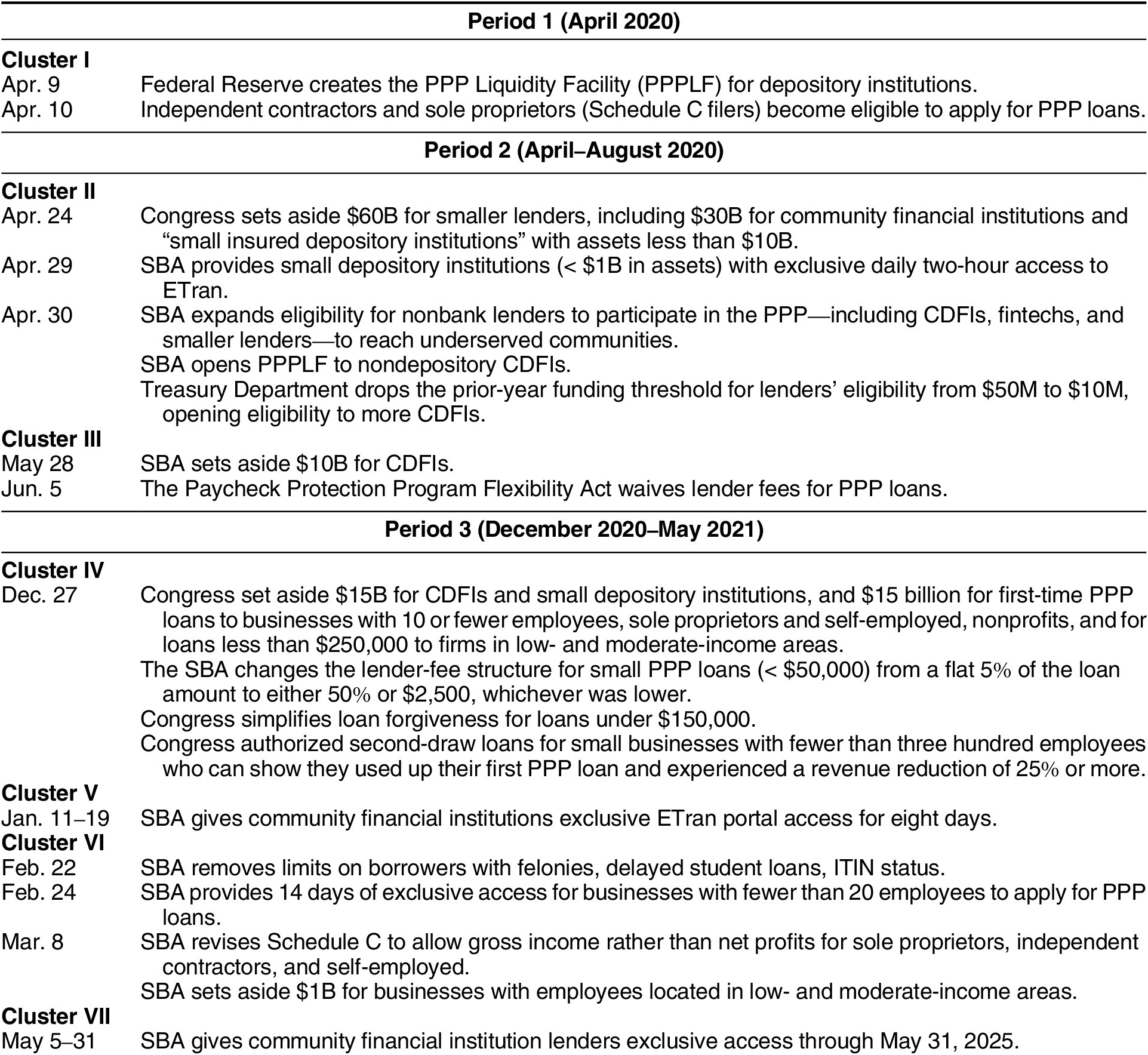

Table 1 Reform Clusters by Period in the Paycheck Protection Program

As the article counts show, media coverage spiked dramatically as the first period closed. This media “tsunami” was important, a coalition leader explained, as focusing attention on the PPP’s lopsided distribution enabled advocates to “get all the key groups, including some conservative-leaning groups, to say this isn’t working.”Footnote 37 Building on this, the Page 30 Coalition worked closely with others to pressure Congress and the SBA to redirect loan flows to neglected businesses and communities. And it came forward with a stream of concrete, expert-based proposals to (1) expand the number and types of PPP lenders, (2) bolster lender capacities to deploy more resources, and (3) reduce barriers to participation among businesses excluded in the first period. Marking a clear case of policy → politics, media outcry and broad mobilization generated immense political pressure on the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress to revise the program. As a Senate Republican staffer mentioned,

when we wrote the original PPP, we were working at a breakneck pace. … By the time you got to subsequent tranches, people were a lot more aware and had an interest in really advocating strongly to get their piece of the pie. The challenge that continued to be debated was the penetration into underserved areas.Footnote 38

Media coverage further amplified the situation, as a trade association representative related:

There was a ton of media attention on the program. … [G]oing in and trying to make the case was easier than it might be if it’s an issue that isn’t topical or isn’t part of the day-to-day conversation.”Footnote 39

This, in turn, provided leverage to organize and lobby. “You cannot discount the importance of the advocates at that point in time,” emphasized a congressional staffer.Footnote 40 When administrative rulemaking was in play, advocates approached the SBA and Treasury. When legislation was on the table, advocates singled out individual lawmakers and their districts:

[We] would send the letter to all the relevant Senate offices, usually just those on the committees. And then you would follow up by asking for a meeting to discuss it. … And then during that, it’s uplifting stories. So, storytelling is, I think, also a piece of it, the person who had a Wells Fargo account but wasn’t able to access the program because their loan was too small to make it worth Wells Fargo’s while, pointing to the deficiencies with the current system.Footnote 41

Heightened pressure led Congress to convene hearings. They addressed the PPP’s racial biases and lack of inclusivity, creating opportunities for the Page 30 Coalition and others to testify, to provide information and stories that defined the problem for legislators, and to propose concrete, informed solutions. Critically, Congress actively reached out to these groups. As a CDFI manager related, “[t]hey were contacting us because they wanted to understand issues that our communities were facing and that banks, CDFI, minority-owned banks were facing.”Footnote 42 A trade association staffer added, “Suddenly they were like, oh, we have these CDFIs, yeah, let’s focus on them, because otherwise, who else were they going to point to do it?”Footnote 43 And backing these concrete suggestions was a remarkable unity of focus within a coalition of diverse groups:

[T]hese groups don’t really play in this sandbox together often, right? … In any other circumstance, it would have been incredibly hard to get all of these groups signed on that swiftly. [But] we knew that we all needed to come together and lock arms. We had one enemy, and the enemy at the time we thought was COVID, but the enemy was structural bias, racism, and the ineptitude of the federal government.Footnote 44

The Outcome

Media coverage, mobilization, and targeted advocacy yielded a stream of policy revisions that reconfigured the PPP and altered the distribution of loans. Table 1 lists key reforms by the three program periods—seven clusters overall—which sought to redirect loan flows in different ways.

First, policy makers revised rules to include and elevate lenders that traditionally served smaller businesses and borrowers in poor and minority communities. On April 30, the SBA expanded eligibility for CDFI and fintech nonbank lenders, and the Department of the Treasury dropped the previous lending threshold from $50 million to $10 million. Both measures increased the number of approvals for these providers to become SBA/PPP lenders, to lend in more places, and to issue larger amounts. In addition, Congress and the SBA dedicated funds and granted privileged access to the portal for CDFIs and depository institutions serving low-income communities or making small loans. The goal was to protect these lenders from competitive free-for-alls and channel funds to communities excluded in period 1. Dedicated funds (set-asides) included $30 billion for these lenders in the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act on April 24, 2020; another $10 billion for CDFIs on May 28; and $75 billion in the December 27 Consolidated Appropriations Act 2021 for CDFIs, small depositories, first-time borrowers, and microbusinesses. The SBA granted exclusive portal access to the smallest depositories in late April 2020, to community financial institutions for the first eight days of third-period applications, and CDFIs for most of May 2021.

Second, the Federal Reserve and the SBA adopted measures to boost the lending capacities of inclusive institutions and newcomers. SBA calls, webinars, and changes to the portal that included automated referral helped them to connect with borrowers and better navigate the system. Yet the “game changer,” as participants term it, was the Fed opening its PPP Liquidity Facility (PPPLF) to them after 21 days on April 30, 2020, which allowed them to move loans off their balance sheets. “[U]ntil the Federal Reserve window opened for us, there was no way we were going to operate at scale,” explained a CDFI loan officer. “What’s 20 million in the line of credit? Literally nothing. We did 200 million in PPP loans. There was no way, with only our normal course of business liquidity instruments, we will get there, guaranteed or not.”Footnote 45

Third and finally, revised eligibility requirements for small businesses and nonpayroll firms closed out in periods 1 and 2 were a second “game changer.” The SBA had authorized lending to Schedule C sole proprietors and independent contractors in the first reform cluster. However, most of those borrowers were not eligible for funds until after March 8, 2021, when the SBA modified Schedule C calculations to allow gross income rather than net profits. “Schedule C for us was a particularly big push,” related a CDFI loan officer and Page 30 Coalition member. “[I]t was a clear way to help those smaller businesses, and 95 or higher percent of Black-owned businesses [that] are one-person businesses.”Footnote 46 This, along with period 3 reforms raising the minimum bank fees for loans to $2,500 and removing limits on borrowers with nonfraud felony convictions, delinquent student loans, or Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) immigrant status, dramatically expanded borrower eligibility and shifted the cost calculation for lenders.

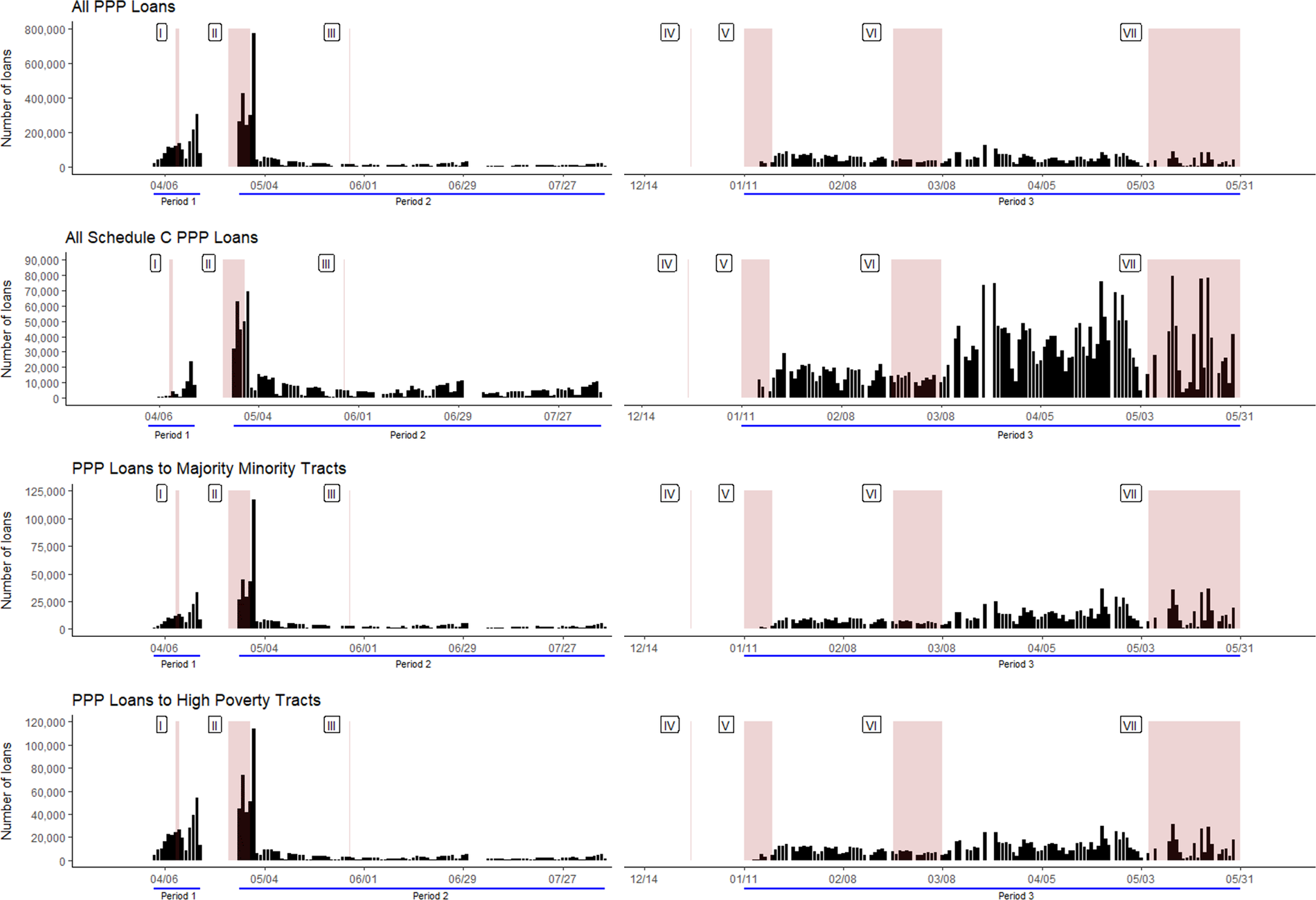

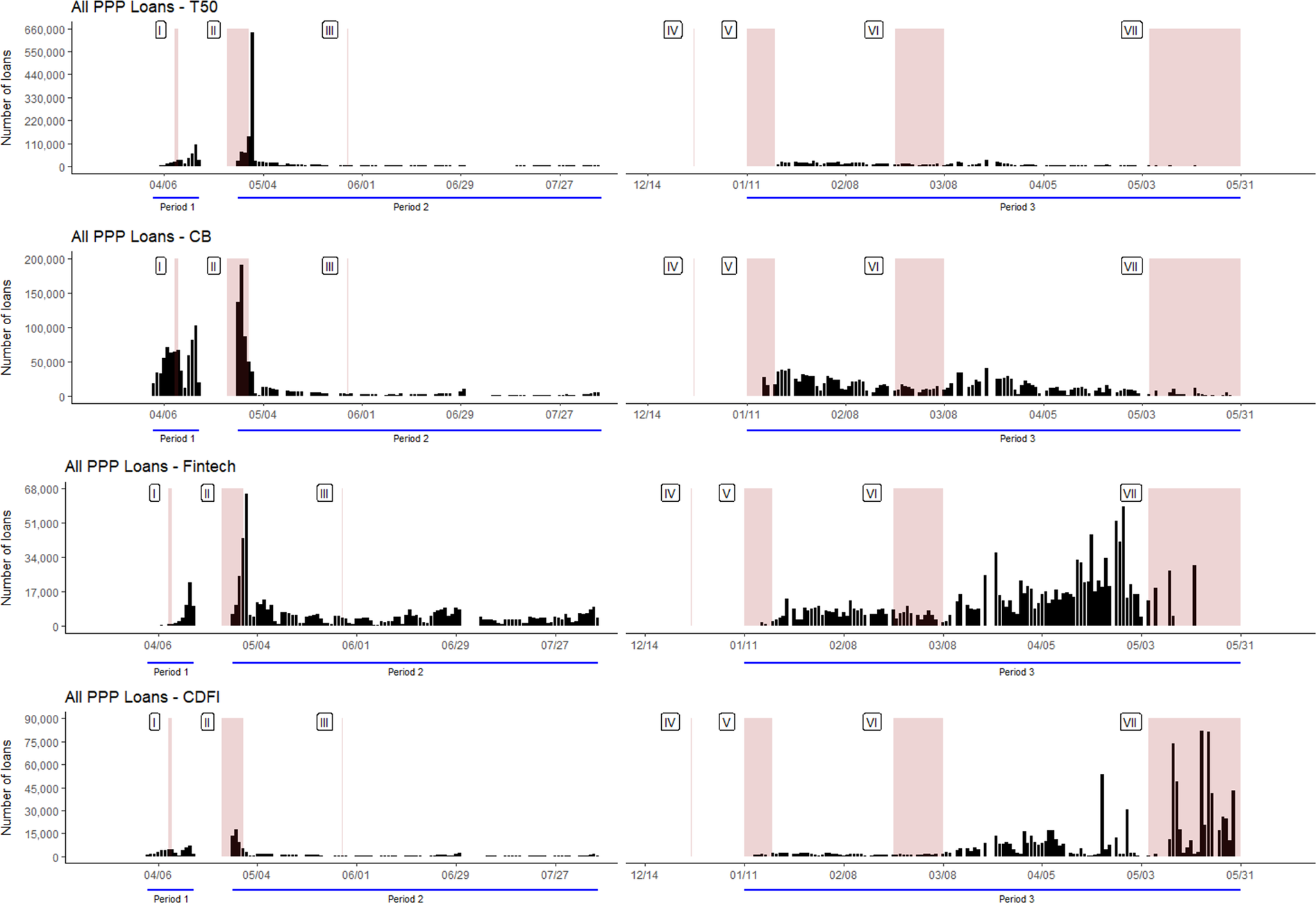

As respondents repeatedly stressed, program revisions changed the PPP for borrowers and lenders, supporting striking shifts in lender ecologies and loan distributions. Figures 3 and 4 overlay reform clusters with charts of daily loans made in each period broken down, respectively, by all loans and borrower subcategories and by lender types, and confirm these observations. There are clear policy-response shifts in flows following five or six of the seven reform clusters. Loan volumes increased in period 1 after cluster I (creating the PPPLF, first eligibility for Schedule C filers) overall, for minority and high-poverty communities, and especially for Schedule C borrowers and fintech lenders that concentrate on the smallest loans. Loan flows also shifted in response to four policy revisions in period 3. Starting loan volumes after reform clusters IV and V (revised fee structures, set-asides and exclusive access for small depositories, small employer organizations, and CDFIs) exceeded most levels from period 2. Lending accelerated and shifted again more dramatically following reform cluster VI (exclusive portal access, lifting restrictions for felons, immigrants, and student loan payment delays, and allowing gross income for Schedule C applicants), and yet again following cluster VII (exclusive CDFI access). Notably, increases after clusters IV and V, but especially clusters VI and VII, were concentrated heavily in loans to Schedule C borrowers and businesses in minority and high-poverty communities on the borrower side, and in fintechs and CDFIs that specialize in serving those communities and borrowers on the lender side. And the dramatic upticks after cluster VII appeared exclusively from CDFIs. The shifts in loan flows that dominated period 3 reflect the impact of policy reforms.

Figure 3 Loans and Reform Clusters by Program Rounds, Overall and by Select Borrower Categories

Figure 4 Loans and Reform Clusters by Program Rounds and Select Lender Types

Loan flow overlays with period 2’s targeted reforms reveal a more complex policy-response picture. Early reforms targeting (nonbank) CDFIs and fintechs on their own had little direct impact. Loans increased after cluster II, but for all lender types. Increases in loans after cluster III were small, delayed, and not confined to CDFIs. Respondents emphasized how exploiting eligibility, getting authorized, making sense of SBA systems, and finding bank partners to access the PPPLF took time for newcomers to SBA 7(a), suggesting delayed policy effects for clusters II and III. Moreover, reforms targeting CDFIs and fintechs like authorization, exclusive access, liquidity support, or even revised fee structures can have little impact on loan flows if there is no payoff for the low-margin, often solo-operator clients that these lenders serve in poor or minority areas. That is, they would have no impact unless and until they were combined with other policy reforms, especially the game-changing Schedule C reforms, which is precisely what we observe. Key reforms in cluster VI (March 8) dramatically increased loan flows through CDFIs and fintechs and unleashed a flood of Schedule C loans and loans to poor and minority communities.

Individually, but especially in combination, endogenously produced policy revisions radically recomposed the PPP and its loan flows across lenders, borrowers, and communities. First, they pivoted the program from mainstream banks to inclusive CDFI and fintech lenders. Loans through all lender types doubled from period 1 to 2, and nearly doubled again from period 2 to 3. Yet lending increased nearly thirtyfold among CDFIs (from 45,300 loans in period 1 to almost 1.27 million in period 3) and fintechs (from 59,000 to nearly 1.74 million). Growth outpaced other lenders by an order of magnitude, driving CDFI and fintech shares from 6% in period 1 to 42% in period 3, displacing mainstream banks from their overwhelming dominance and 90% share in period 1.

At the same time, program revisions opened the gates for PPP loans to the kinds of traditionally excluded businesses that predominate in underresourced and Black and brown communities. From period 2 to 3, PPP loans to Schedule C borrowers skyrocketed from about 128,500 to almost 3.2 million, or almost 51% of all period 3 loans, with CDFIs and fintechs leading the way by issuing over two million (or over 64%) of Schedule C loans. And with these dynamics came shifts in the socioeconomic composition of places receiving loans. Five- to sixfold increases in loan numbers for high-poverty and majority nonwhite districts boosted loans to high-poverty and majority nonwhite districts to over 532,000 and 1.9 million, respectively, in period 3. Program revisions raised high-poverty-district shares of PPP loans to 10% and minority-district shares from 19% to 36%. Finally, they also raised loan-to-business ratios in high-poverty and minority districts from 0.07 to 0.49 and from 0.06 to 0.39, respectively, closing the gap with more affluent and majority-white ones.Footnote 47

In sum, process tracing reveals that the PPP’s initial architectures induced a macrodevelopmental trajectory of politics and policy change that shaped and shifted loan distributions across places. A new policy to support small businesses replicated racial and class biases in banking, triggering media attention and congressional hearings that provided windows and leverage for group mobilization and targeted advocacy. Policy fueled politics, resulting in administrative and legislative changes reconfiguring the PPP’s lending ecologies and flows.

Alternative Explanations

The strength of our inference also depends on the viability of alternative explanations for shifting distributions. One alternative emphasizes a natural progression by firm size in which large firms precede or crowd out small firms in accessing program benefits. Like our account, this one rests on observations of the PPP and other programs that larger firms are more informed about opportunities and protocols than smaller firms, possessed greater resources, organizational capacities, and connections for leveraging public benefits, and were more attractive to banks or other program providers. Unlike our account, the alternative suggests progression dynamics that operate independently of the PPP’s design, subsequent revisions, and one or two expected loan flow patterns. We might expect succession, with better-informed large firms storming out of the gates and getting loans first, followed by medium-sized small businesses, then microemploying organizations, and lastly solo operators as they gather information about the program. Or we might expect exhaustion or crowding-out processes, with better-resourced large firms muscling their way into the program and tapping all the funds they need before progressively smaller businesses can gain access.

Interviews and examination of PPP loans and coverage by firm size do not support this account. Interviewees stressed that banks turned away small firms that were informed and actively seeking loans, indicating that information differences alone were not driving outcomes; banks had to reach out to educate larger firms. Respondents also stressed how net profit rules kept Schedule C solo operators out and that those businesses typically could not obtain funding until those rules changed. Moreover, loan counts and cumulative coverage rates in figures D1 and D2 in online appendix D show similar loan flow patterns for large, medium, and small employers, with simultaneous surges and plateaus rather than staggered sequences. They also provide no evidence that small employers had to wait until larger ones had their fill. All three smaller firm classes could access funds fully despite barely a quarter of the largest firms being covered. Moreover, while surges for Schedule C operators lagged those for larger firms, they did not occur either right before or soon after other groups flattened, but nearly a year later, following revision of net profit rules, indicating policy rather than natural progression effects. Size matters, but its distributional impacts depend heavily on policy architectures.

A second argument for shifts in loans focuses on the “exogenous shock” of George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, and the subsequent Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Protests and pressures on lenders rather than policy shifts might have produced loan flows to minority communities. Interviewees confirm how BLM dynamics generated such pressures in the PPP: “After George Floyd, it was hard for Republicans to be like … ‘The Blacks don’t need any money,’” a staffer related.Footnote 48 In that context, a CDFI officer explained, the PPP “was one more well-documented way that Black and brown borrowers were being left out … something that we could work together on.”Footnote 49 However, loan flow patterns in figure 3 indicate little if any direct impact of BLM dynamics on loans to minority communities. Only very modest and delayed increases to those communities occurred during the summer of 2020, which were dwarfed by upticks after cluster VI reforms almost a year later. This is not to dismiss BLM effects. To the contrary, they powerfully impacted loan flows, but indirectly, via policy revisions, by amplifying media attention and public criticism already underway, keeping issues of racial inequities in the PPP highly salient (figure 2) and providing advocates with ammunition to push for reforms.

Quantitative Findings

We further engage these and conventional-politics accounts via quantitative analyses and panel models of the distribution of PPP loans (loan ratios) across congressional districts. We begin with models based on conventional-politics approaches and then quantitatively model some IP-PIT-inspired implications derived from qualitative findings.

Conventional Politics

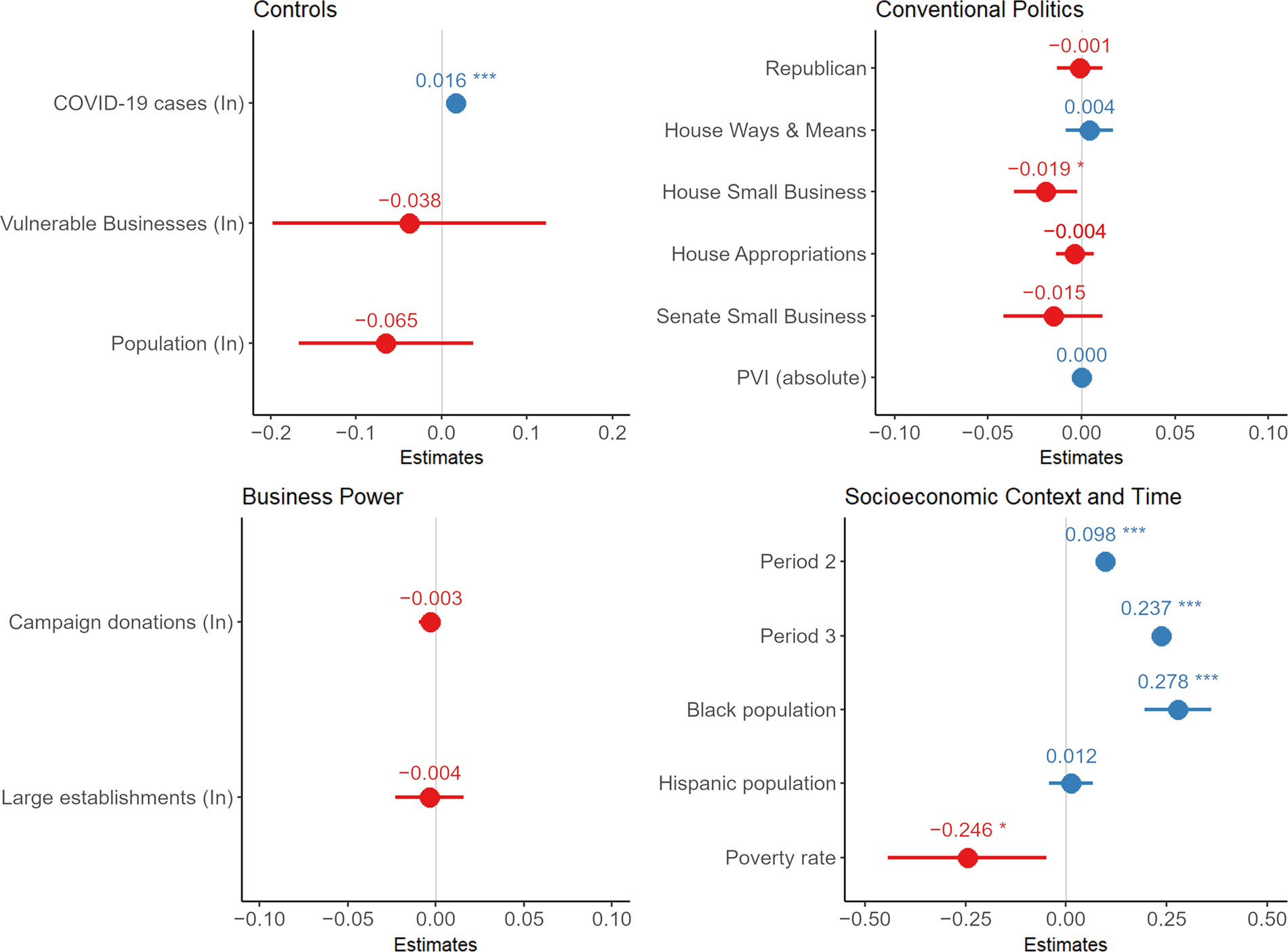

Figure 5 reports findings from conventional-politics models by plotting coefficients from the full model we developed via the model-building process tabled in E1 in online appendix E. We start with a baseline (M1) that controls for population, urbanization, COVID-19 cases, vulnerable sectors, state fixed effects, and program periods. To that baseline, we add variables for conventional politics and business power, separately (M2 and M3) and together (M5), and after including socioeconomic characteristics in a new baseline (M4), repeat the processes of adding politics and business variables (M6, M7) to arrive at the full model (M8).

Figure 5 Coefficient Plots of Full Random-Effects Model (Model 8)

Coefficients for control factors (figure 5, top left panel), socioeconomic conditions, and time (bottom right panel) return significant results. Loans to districts increase with COVID-19 cases and the Black population, increase dramatically in periods 2 and 3, and decrease with poverty rates. In contrast, only one of the coefficients for the eight conventional-politics and business power variables (top right and bottom left panel) reaches statistical significance—whether the member served on the House Committee on Small Business that crafted the PPP’s core architecture. Contrary to conventional-politics expectations, that coefficient is negative, not positive. Moreover, the array of models in table E1 in online appendix E confirms these results. Four politics variables reach significance in reduced models. Yet donations, like committee membership, return negative effects; the Partisan Voting Index shows a positive rather than the expected negative effect; and the party, donations, and Partisan Voting Index variables lose significance when controlling for socioeconomic conditions and time, leaving only one negative committee-membership effect.

We conducted extensive robustness checks to assess whether this strikingly poor performance of conventional-politics models was an artifact of our modeling or data choices (online appendix F). We refit models using all loans and just first loans, with and without flagged loans. We use different dependent variables (log loan numbers, log loan values, loan and value ratios) and measures of politics to capture battleground places, core Republican districts, presidential affiliation, and campaign donations from financial versus nonfinancial industries. We even fit models separately for each loan period with each dependent variable (table E4 in online appendix E). Yet these models consistently return null or negative results, generating only occasional supportive results in a particular specification or period and providing little explanation of the distribution of PPP loans across districts.

IP-PIT-Based Arguments and Findings

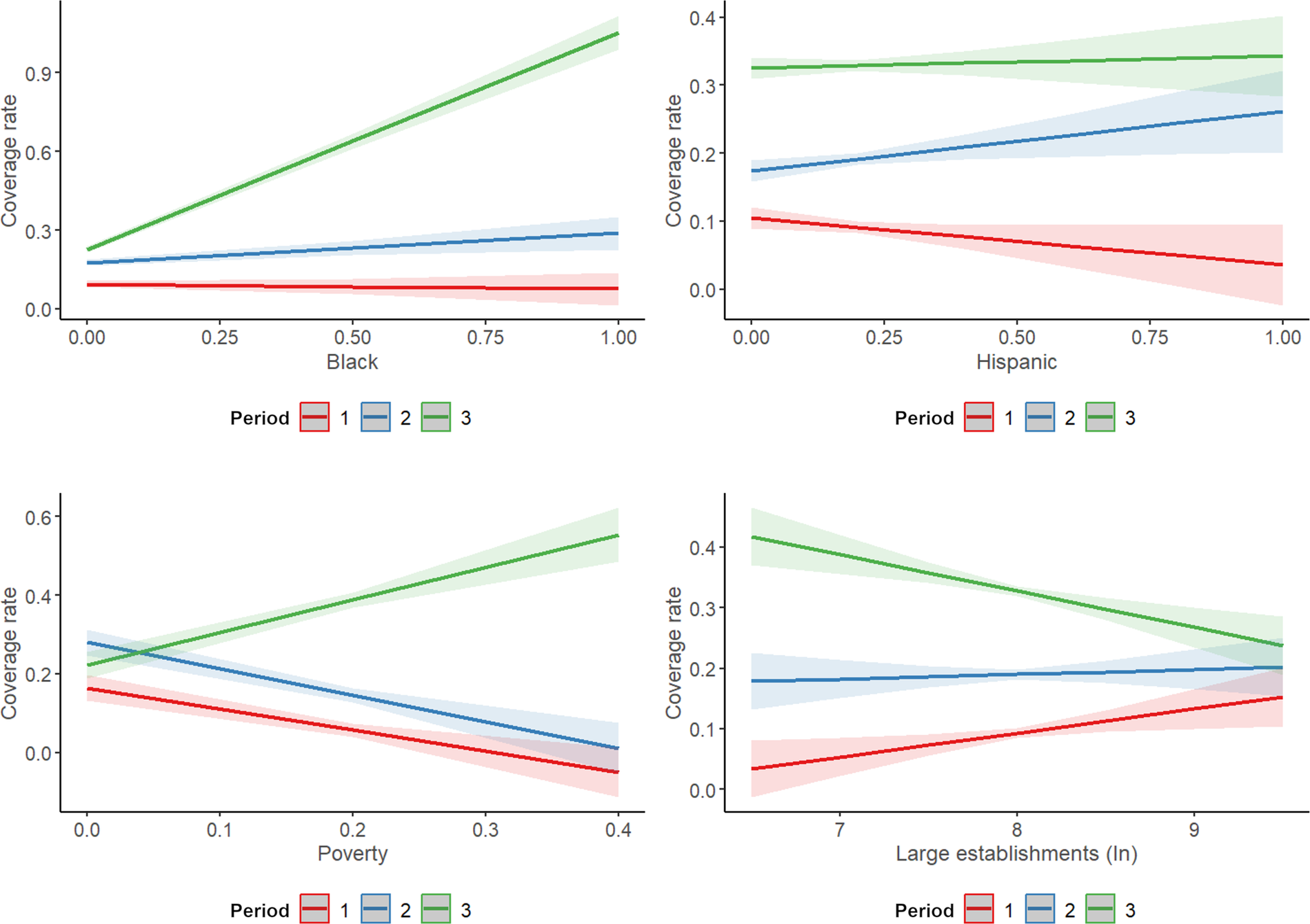

In contrast, the limited explanatory power of conventional-politics approaches jives well with IP-PIT ideas about critical junctures and path dependence. Moreover, our qualitative findings about how policy generated politics and program trajectories imply testable expectations about how socioeconomic factors shaped PPP distributions over time. As negative feedback induced by the PPP’s initial architecture and distributional biases fuels policy changes recalibrating lenders and loan flows, we expect the impacts on flows of ethnoracial composition, poverty, and large establishments to shift. We expect negative effects of minority composition and poverty on loans in period 1 and a positive impact of larger establishments. Those effects will diminish and even reverse in periods 2 and 3 as policy reforms reconfigure the terrain for borrowers and lenders.

To assess these ideas, we add interaction terms between program periods and four measures of socioeconomic conditions in districts to our entire model. Based on models tabled in E2 in online appendix E with estimated effects plotted in figure 6, the results in the top panel reveal time-varying effects. Slopes in period 1 for percent Black, Hispanic, and poor indicate negative effects on loans, while large firms have a positive relationship. Over time, these effects reverse. Lending in periods 2 and 3 is more inclusive, with loans flowing to poorer, more diverse districts with fewer large establishments. These trends reflect policy reforms favoring the smallest, solo-operator businesses in some of the poorest and minority districts.

Figure 6 Time-Dependent Context Effects on PPP Loan Ratios by Period

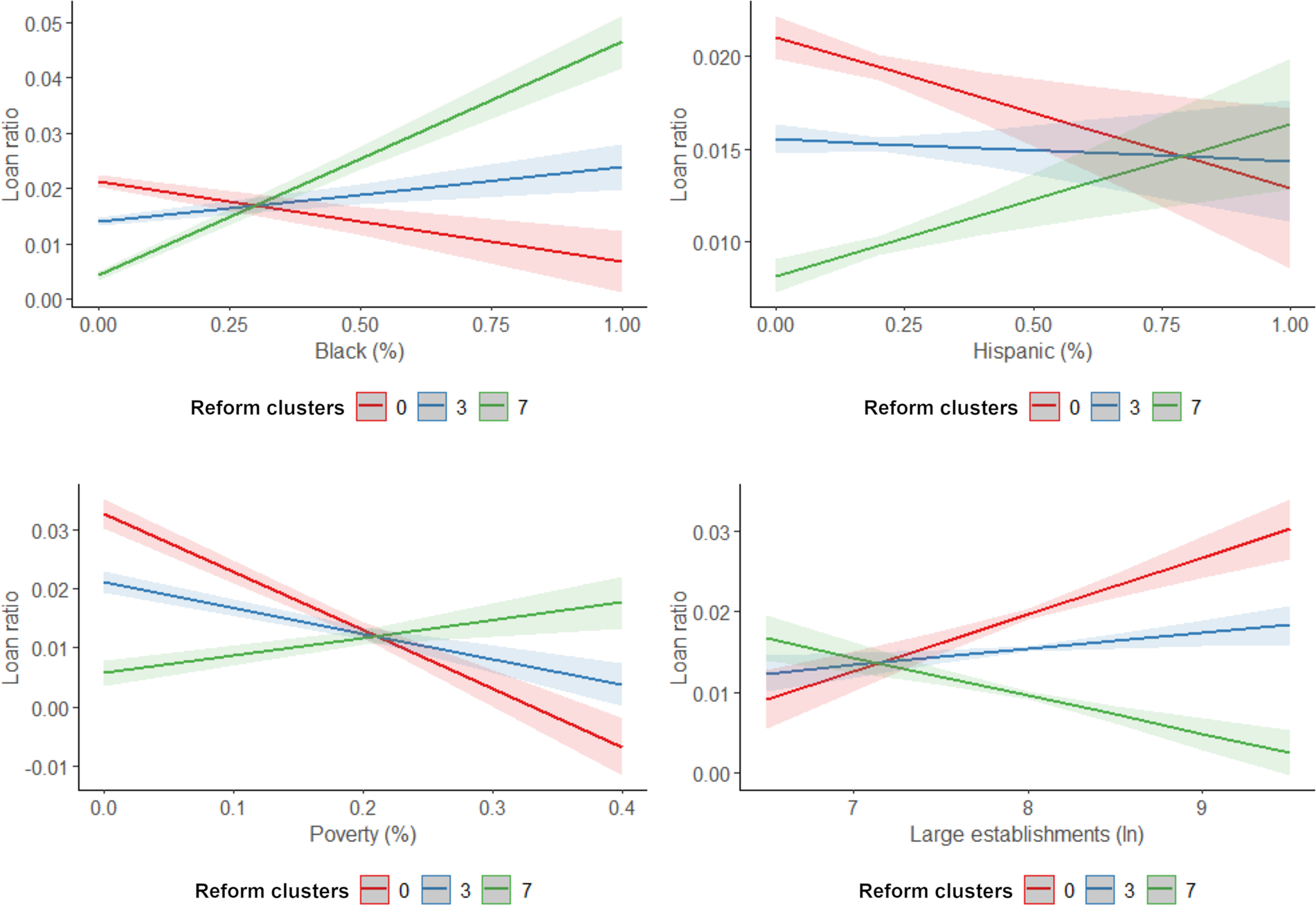

In a final step, we reanalyzed these relationships and time-varying effects using a more fine-grained approach based on our qualitative findings. We fit models that use weekly loan counts as outcomes and reparametrize time using cumulative counts of critical media articles, congressional hearings, and reform clusters. Instead of breaking down PPP lending into three program periods, these models estimate separate interaction effects for saliency, hearings, and clusters as they evolve to more directly tap backlash politics and policy impacts highlighted in our IP-PIT account. Tabled in E3 in online appendix E, these models return significant interaction coefficients for all three moderator variables, providing clear evidence of how negative feedback, public criticism, and policy revisions reshaped loan flows. Figure 7 charts the interaction effects for policy revisions. Before any reform, higher poverty and Black or Hispanic population shares decreased, and large-business prominence increased loan flows. Yet as policy reforms accumulate, these effects change, switch, and result—in reform cluster VII—in positive associations of loan flows with Black, Hispanic, and poverty covariates, and negative ones for large businesses. These results parallel those for saliency and hearings and those shown above for the three-period analysis, and confirm our key finding: policy revisions reconfigured how the program allocated funds, radically shifting the sensitivities of loan flows to district socioeconomic conditions.

Figure 7 Time-Dependent Context Effects on PPP Loan Ratios by Reform

Conclusion

What explains the distribution of PPP funds across congressional districts? While prior scholarship advances conventional-politics ideas, analyzing the full corpus of loans raises questions for such politics → policy → outcome accounts. Electoral dynamics, committee membership, campaign donations, or industry clout are largely uncorrelated with distributional outcomes, and respondents repeatedly emphasized how the pandemic thoroughly undermined conventional political processes. This underscores the need for an alternative account. Based on interviews, process tracing, and additional quantitative modeling, we turned to institutional politics (IP-PIT) to better explain the PPP and its trajectories.

IP-PIT emphasizes how policies generate politics, distributional outcomes, and feedback loops, suggesting a policies → politics/outcomes → policies sequence (Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Reference Pierson2004; Sorelle Reference Sorelle2023). This led us to anchor our study in a qualitative analysis of temporal variation in policy architectures, politics, and loan access across the program’s three periods. However, we also engaged conventional and IP-PIT approaches via quantitative analyses of PPP loan flows. While blending different approaches and methodologies is unusual and ambitious, it lets us address and contribute to debates over the linkages between politics and policy in ways that otherwise might not be possible.

Contributions

The first of its kind, our study contributes empirical and theoretical insights into not just one of the most significant public interventions in the US economy since the Great Depression, but also policy making during crises. Our findings highlight likely general limits on the ability of conventional-politics approaches to explain such issues. Instead, core IP-PIT concepts of critical junctures, policy feedback, and path-dependent trajectories apply beyond epochal institutional changes, including policies temporarily implemented as emergency measures that may or may not yield enduring resets. As shown above, the COVID-19 pandemic sparked a critical “crisis” juncture that suspended normal politics, creating the opportunity for a program that astonished participants for its scale, speed, and scope. Once in place, PPP “policies created new politics” (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2019; Jacobs and Weaver Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015) that set the program on a two-year path. Its initial architectures and distributions generated new interests and organizations like the Page 30 Coalition (North Reference North1990; Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1996). They mobilized a range of constituencies from CDFIs to Black and Hispanic chambers of commerce (Moynihan and Soss Reference Moynihan and Soss2014; Sorelle Reference Sorelle2023; Thurston Reference Thurston2015). They reframed public discourse, calculations, and debate as media reports, academic studies, and hearings piled up (Dobbin Reference Dobbin1994). They also induced backlash politics (Jacobs and Weaver Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Patashnik and Zelizer Reference Patashnik and Zelizer2013; Schneiberg Reference Schneiberg2005) and policy revisions that reconfigured loan flows and their sensitivities to socioeconomic conditions.

In short, the PPP’s evolution and distributional outcomes were rooted in a critical crisis juncture, followed by policy choices that generated feedback effects and endogenously produced developmental trajectories. Moreover, consistent with IP-PIT claims, the impact of socioeconomics and politics on loan flows depended on timing, shifted across rounds, and became a causal factor in its own right.

Our work also advances theoretical understandings of key IP-PIT concepts. First, it indicates varieties in critical junctures and their dynamics. Specifically, it highlights junctures in crisis moments that upend business-as-usual politics but without systemic struggles over the rules of the game or fundamental challenges to their legitimacy. The COVID-19 pandemic took decision makers by surprise. It confronted them with impending existential losses and profound uncertainty that trumped other preferences and forced them to react immediately through emergency instead of conventional policy making. This opened a window for innovation. Yet policy makers’ beliefs were also decisive: beliefs that COVID-19 was a short-term crisis to be managed in the here and now, and that policy solutions, however out of line with broader preferences, were temporary measures to be set aside or revisited in the near future. In these crisis junctures, decision makers are far more likely to select short-term “off-the-shelf” solutions rapidly rather than pursue systemic change (Cohen, March, and Olsen Reference Cohen, March and Olsen1972; Kingdon Reference Kingdon2011).

Second, our study also contributes to IP-PIT analyses of path dependence by shedding new light on dynamics and conditions for negative policy feedback. As with positive feedback effects, negative feedback involves political processes endogenously generated by a new institution, but which erode support and create pressures for change (Clemens Reference Clemens1997; Daugbjerg and Kay Reference Daugbjerg and Kay2020; Jacobs and Weaver Reference Jacobs and Weaver2015; Patashnik and Zelizer Reference Patashnik and Zelizer2013; Schneiberg Reference Schneiberg2005; Thurston Reference Thurston2015; Weaver Reference Weaver2010). New institutions or policies can foster backlash politics by creating losers and opponents with new grievances who form new coalitions to unsettle settled policy and advance reform.