13.1 Introduction

An environment of ‘geopolitical suspicion’ toward China aggravated by the pandemic of the new coronavirus (Covid-19) should affect the 5G supply chain, bringing impacts on the strategy and competition in Brazil. At a time when we need to make a quantitative and qualitative leap in technology, it would be interesting to let the competition work: Chinese fighting with Americans, with Nordics, to see who serves us better. [But] at this time when we should take this plunge, this ‘cloud of suspicion’ comes and creates a geopolitical problem in something that was strictly economic.

This diagnosis appeared in an interview by Mr. Paulo Guedes – Jair Bolsonaro’s Finance minister – granted to CNN Brazil, in July 2020. In the conversation, Mr. Guedes unabashedly suggested that, despite the advantages of competition, the suspicion that China was to blame for the pandemic of Covid-19 could create unexpected costs for countries adopting Chinese technology. The minister further claimed that, for geopolitical reasons, China could possibly decide to “turn off the buttons” and interrupt communication and security services and declared that “from a geopolitical perspective we are on Trump’s side.”

Brazil ended up never banning Huawei from selling to 5G suppliers, thanks to enormous pressure from local companies and from the Chinese government, but these declarations illustrate the animosity the Bolsonaro government maintained toward China throughout its four years in office. This confrontational, often aggressive tone included public declarations by government officials, as the one quoted above, tweets, and even jokes – like the one made by the then Minister of Education, and later Executive Director of Brazil at the World Bank Abraham Weintraub – about the Chinese accent speaking Portuguese.Footnote 1

The animosity described precedes the pandemic of Covid-19 but worsened after it. During the crisis, the president, his sons, and other government officials frequently associated the country with the virus and actively helped spread fake news suggesting the virus was created purposefully by China to increase its international standing.Footnote 2 These comments raised concerns among Chinese officials and ultimately led to an unusually harsh response from the Chinese Ambassador to Eduardo Bolsonaro, the president’s son and then president of the Foreign Relations Commission of Brazil’s Lower Chamber. There were also speculations that delays in the export of inputs for the production of vaccines were a quiet response to the attacks.

Irrespective of the president and his family’s personal views about China, from an international relations perspective the confrontational tone that permeated relations with the country during the Bolsonaro administration is intriguing, to say the least. Even considering the enormous effect Chinese growth had on world markets in the past two decades, the Brazilian case still stands out as a country transformed – not only economically but also politically – by the expansion of Chinese markets.

Still, it can always be argued that the president’s behavior toward trading partners is the result of multiple pressures, including those exerted by those harmed by Chinese competition.

The indifference of winners from trade with China to those attacks, however, poses a puzzle to international political economists. Why did groups that benefited so much from the expansion of Chinese markets not publicly stand up to defend the country from the government’s attacks? The indifference of winners from Chinese trade to the anti-China stance that characterized the Bolsonaro years is the object of this article. Before moving forward, however, it is important to identify winners and losers from the boom in Chinese-Brazilian trade observed since the early 2000s.

13.2 Establishing Winners and Losers in Brazil-China Trade

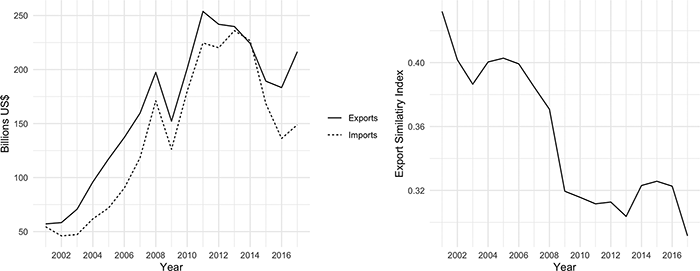

Since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), bilateral trade has grown exponentially between the two countries (Figure 13.1a). In less than ten years, China went from Brazil’s twelfth major export destination to becoming the country’s main trade partner. In 2000, Brazil received 2.3 percent of its imports and sent 2.0 percent of its exports to China (by value); in 2021, these numbers had risen to 21.7 percent and 31.3 percent, respectively. Thanks to a substantial expansion of Chinese trade (Figure 13.1a), Brazil experienced an unprecedented boom in trade and fiscal revenues and an acceleration of economic growth rates in the past decade (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2015).

Figure 13.1 Brazil-China trade indicators. (a) Brazilian exports to and imports from China. (b) Export similarity index.

Note: (a) Presents trends in Brazilian imports and exports to China, and (b) displays the export similarity index [source: UN Comtrade]. The export similarity index captures the competition between China and Brazil in the world market. It is calculated as ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the share of product

is the share of product ![]() in the exports of Brazil to the world, and

in the exports of Brazil to the world, and ![]() is the share of product

is the share of product ![]() in the exports of China to the world.

in the exports of China to the world.

As Figure 13.1b shows, Brazil and China developed a commodity-for-manufacture pattern of trade. Thanks to this pattern, Chinese trade produced a remarkably positive shock in Brazil’s agro-exporting areas, and hurt industrial sectors like textiles, electronics, and machinery (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2015; Paz Reference Paz2018).

Chinese demand for commodities has produced an unprecedented shock in agro-exporting areas (Costa et al. Reference Costa, Garred and Pessoa2016). To cope with the fast-growing soy market and its subproducts, the agricultural frontier has advanced toward the states of Mato Grosso, Goiás, and Mato Grosso do Sul, at the expense of South America’s largest savanna, the so-called Cerrado (Oliveira and Schneider Reference Oliveira and Schneider2016; Spring Reference Spring2018). Traditional agro-exporting states, such as Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná, also gradually replaced other crops (cotton, corn, rice, and tobacco) with soybeans.

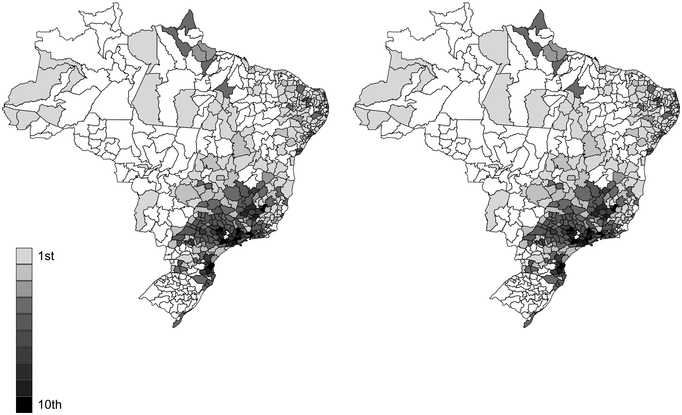

As both agribusiness and industry are clustered geographically in Brazil, the income shocks associated with Chinese trade were not limited to citizens working in the tradable sectors. As most affected municipalities become wealthier/poorer, residents working in services also experience the impact of these “localized” shocks (Figure 13.2).

Figure 13.2 Chinese import (left) and export (right) shocks per worker by Brazilian microregions.

Note: Variables are expressed in deciles (Costa et al. Reference Costa, Garred and Pessoa2016).

It would be natural to expect, thus, that as much as it makes sense for losers from Chinese trade to share and even exacerbate the government’s anti-China sentiment, those benefited by booming exports to China should actively oppose the confrontation of their main market.

Students of the politics of international trade have long investigated economic determinants of trade attitudes (Kaltenthaler et al. Reference Kaltenthaler, Gelleny and Ceccoli2004; Mansfield and Mutz Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009; Milner and Tingley Reference Milner and Tingley2011). Most of this work evolved within the Open Economy Politics (OEP) paradigm and assumes that these attitudes reflect individual self-interest derived from well-established economic models.

The Stolper-Samuelson – or factor-endowment – model assumes costless intersectoral mobility of factors of production and posits that trade benefits (harms) individuals who own relatively abundant (scarce) factors. The Ricardo-Viner – or specific-sectors – model relaxes the assumption of full-factor mobility and postulates that trade favors individuals who are employed in the export-oriented sectors (intensive in abundant resources) and hurts those who are employed in import-competing sectors (intensive in scarce resources). It follows that pro- and anti-trade preferences should form along factoral and sectoral lines, respectively, depending on the level of factor mobility observed in a given economy (Rogowski Reference Rogowski1989; Hiscox Reference Hiscox2002).

Empirical work on the determinants of trade preferences at the individual level has mostly focused on the developed world. These studies are hardly conclusive, but several of them found a consistent association between high skills (abundant factor) and support for free trade in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and interpreted this as evidence in support of the factor-endowment model (Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Kaltenthaler et al. Reference Kaltenthaler, Gelleny and Ceccoli2004; Mayda and Rodrik Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005).Footnote 3

Recent research has challenged this interpretation, though, questioning the centrality of material interests and moving toward examining the impact of ideas, values, and attitudes on the understanding of trade views (Hiscox Reference Hiscox2002; Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Mansfield and Mutz Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009; Lü et al. Reference Lü, Scheve and Slaughter2012; Ardanaz et al. Reference Ardanaz, Murillo and Pinto2013; Sabet Reference Sabet2016; Rho and Tomz Reference Rho and Tomz2017).Footnote 4

Another strand of this literature, however, argues that weak empirical evidence of the relevance of self-interest stems from its overly strict definition, derived directly from individual factor-ownership or employment in tradable sectors. Mansfield and Mutz (Reference Mansfield and Mutz2009), for example, argue that strictly defined self-interest rarely shapes policy preferences because people do not understand the connection between personal well-being and public policies. Rather, they maintain that trade preferences are sociotropic and are formed based on how people believe policies affect their community.

Survey experiments indicate that sociotropic preferences should not be seen as automatic replacements for individual-level information, as both seem to interact depending on the context. Yet, it emerges that individuals typically do not respond to positive country-level information by increasing their approval rates for trade; instead, they tend to react by lowering their approval rates when presented with negative information. For instance, when given negative information about their own sector, individuals may become concerned about the potential loss of their own jobs (Schaffer and Spilker Reference Schaffer and Spilker2019).

Other authors draw from the economic voting literature to advocate for more realistic meso-level theories of interest formation, rather than narrow self-interest (Fordham and Kleinberg Reference Fordham and Kleinberg2012; Ansolabehere et al. Reference Ansolabehere, Meredith and Snowberg2014). They assert that local economic conditions influence individuals’ perception of government’s management of the economy and that it is very difficult to separate individual from group interests. People may know little about trade, but they learn from family, friends, neighbors, coworkers, business leaders, and organized groups; individuals living near one another are likely to share interests and experience economic booms and crises. Negative characterizations of partner countries resonate with those that are harmed by trade, such as business leaders and their employees, but also with a whole network of secondary economic beneficiaries of activities in these sectors (Kleinberg and Fordham Reference Kleinberg and Fordham2010; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018a).

Along these lines, several studies have turned their focus to the political impact of localized shocks associated to trade (Margalit Reference Margalit2012; Ardanaz et al. Reference Ardanaz, Murillo and Pinto2013; Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Quinn and Weymouth2017). Those studies posit that, when trade shocks hit a specific region, income effects are not restricted to those working in affected sectors but are broadly felt by residents in that region.

More directly and related to this chapter, scholars have found that localized income shocks from trade with China cause a higher vote share for the Democrats (Che et al. Reference Che, Lu, Pierce, Schott and Tao2022) and push voters to political extremes (Autor et al. Reference Autor, Dorn and Hanson2016) in the United States. In Europe, import shocks from trade with China are associated with an increase in support for nationalist and isolationist parties Colantone and Stanig (Reference Colantone and Stanig2018b), and to a general shift to the right among the electorate (Broz et al. Reference Broz, Frieden and Weymouth2021).

Below, we report the results of a national survey conducted in Brazil, which investigates how localized income shocks related to trade with China affect individuals’ perception of integration with the country as posing an opportunity or a risk to Brazil.

13.2.1 The Survey: Trade and Brazilians’ Perceptions of China

Do trade shocks from China affect Brazilians’ perceptions of its main trade partner? To answer this question, we conducted a stratified survey in Brazilian municipalities that experienced strong income shocks associated with import and export from trade with China, as calculated by Costa et al. (Reference Costa, Garred and Pessoa2016), and also in a control group of residents in areas unaffected by Chinese trade.

Costa et al. retrieved data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics to determine changes in labor market outcomes of regions producing manufacturing goods affected by rising Chinese import supply and localities specializing in raw materials demanded by China, for four decades: 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. Our analysis uses the 2010 estimates, which are the closest to the survey. The calculation of export and import shocks is described in detail in the Appendix.

With these data in hands, an online survey companyFootnote 5 conducted a survey of perceptions of economic integration with China, fielded in September 2018. To capture variation in trade shocks, localities were classified into three strata, according to whether they experienced large import shocks, large export shocks, or neither.

Overall, 15 percent of the national population lives in municipalities that suffered export shocks larger than US$1,190 per worker, and 23 percent of the national population lives in municipalities that suffered import shocks larger than US$880 per worker. The resulting stratified national sample of 1,352 cases was selected to be representative of these proportions at a subnational scale, and it is described in Table 13.A.1 in the Appendix.

Each respondent was asked the question “How much do you agree with the sentence: stronger ties with China will bring more risk than opportunities to Brazil,” with answers varying along an ordinal scale ranging from “strongly disagree,” to “strongly agree,” our main dependent variable [RiskOpportunity].Footnote 6

The survey gathered additional relevant information on individuals’ educational level [Education] and income [income], which according to the factor-endowment model, should have a negative impact on views about trade in developing nations.Footnote 7 Information was also gathered concerning self-reported ideology [ideology], a self-reported scale ranging from 1 to 10, where 1 represents extreme left-wing beliefs and 10 indicates extreme right-wing beliefs, age of the respondent [Age], and sector of employment (agriculture/extractivism, manufacturing, and services) [employment].

The main model of interest can be defined as follows:

where individual denotes individual characteristics, ![]() represents locality and

represents locality and ![]() represents one individual.

represents one individual.

13.2.2 Results

The models presented below test the hypotheses that individuals’ perception of China as predominantly a risk (rather than opportunity) should increase/decrease with the magnitude of the import/export shock suffered by her locality. We used ordered logit models as they preserve the maximum amount of the information in the dependent variable without imposing linearity on the underlying relationship between the explanatory variables and the five-point scale on which individual responses are calibrated (Mayda and Rodrik Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005).

Model 1 includes only individual characteristics as explanatory variables (See Table 13.1). Model 2 adds the main variables of interest, that is, import and export shocks to the respondent’s locality. Model 3 adds sector of employment together with trade shocks, and model 4 contemplates an interaction of sector of employment and trade shocks. The rationale is that those employed in the manufacturing industry should be more sensitive to import shocks, while those employed in agriculture should be more responsive to export shocks.

Table 13.1 Respondents’ assessments of ties with China

| Model 1 RiskOpportunity | Model 2 RiskOpportunity | Model 3 RiskOpportunity | Model 4 RiskOpportunity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.255 | 0.252 | 0.261 | 0.263 |

| (0.143) | (0.143) | (0.144) | (0.143) | |

| Age | −0.0151* | −0.0151* | −0.0147* | −0.0147* |

| (0.00700) | (0.00704) | (0.00712) | (0.00713) | |

| Income | 0.00311* | 0.00318* | 0.00330* | 0.00331* |

| (0.00153) | (0.00155) | (0.00159) | (0.00159) | |

| Education | −0.0933** | −0.0936** | −0.0905** | −0.0919** |

| (0.0313) | (0.0313) | (0.0315) | (0.0317) | |

| Ideology | 0.0239 | 0.0220 | 0.0232 | 0.0233 |

| (0.0191) | (0.0194) | (0.0198) | (0.0196) | |

| Import shock per capita | 0.456*** | 0.450*** | 0.416** | |

| (0.126) | (0.130) | (0.141) | ||

| Export shock per capita | 0.0810 | 0.0957 | 0.0932 | |

| (0.0677) | (0.0764) | (0.0756) | ||

| Works in manufacturing | 0.234 | −0.00938 | ||

| (0.172) | (0.272) | |||

| Works in agro-extractive activities | −0.744 | −0.866 | ||

| (0.928) | (1.361) | |||

| Works in manufacturing × Import shock | 0.308 | |||

| (0.206) | ||||

| Works in agro-extractive × Export shock | 0.0825 | |||

| (0.477) | ||||

| Cut 1 | −2.992*** | −.917*** | −.873*** | −2.882*** |

| (0.310) | (0.317) | (0.329) | (0.325) | |

| Cut 2 | −1.278*** | −1.200*** | −1.153*** | −1.161*** |

| (0.313) | (0.321) | (0.333) | (0.330) | |

| Cut 3 | 0.716* | 0.799* | 0.848* | 0.842* |

| (0.311) | (0.319) | (0.333) | (0.330) | |

| Cut 4 | 2.743*** | 2.828*** | 2.878*** | 2.872*** |

| (0.348) | (0.357) | (0.371) | (0.368) | |

| Observations | 1,352 | 1,352 | 1,352 | 1,352 |

| AIC | 3,630.1 | 3,629.2 | 3,630.1 | 3,633.1 |

Note: The dependent variable RiskOpportunity is “Stronger ties with China will bring more risk than opportunities to Brazil.” All models are estimated through ordered logit. In parentheses, standard errors clustered at a microregional level. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The interactive effects of Model 4 are not significant, meaning that at an individual level, there are no differences in the import shock for those working in manufacturing and in export shocks for those working in agro-extractive sectors. This implies that within a specific area, being employed in a sector that experiences losses or gains does not significantly impact views of China compared to other residents. These findings strengthen the argument that when trade shocks are localized, their income effects extend beyond employees in the directly affected industry, encompassing those working in non-tradable sectors within the same locality. In other words, the impact of trade shocks on attitudes toward China is not limited to those directly employed in the affected sector but also affects individuals working in other industries in the same geographical area.

Among various individual attributes, education emerges as the most crucial factor. Brazilians with higher levels of education are less inclined to perceive relations with China as risky. This observation is particularly noteworthy, given the scarcity of high-skill labor in the country. It suggests that education likely influences attitudes such as cosmopolitanism or exposure to free-trade ideas, rather than being solely determined by economic factors (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Ardanaz et al. Reference Ardanaz, Murillo and Pinto2013). Furthermore, the research findings align with existing literature, indicating that men and older citizens tend to view integration with China more favorably. On the other hand, although income shows statistical significance, its practical relevance in shaping attitudes appears to be minimal.

Most importantly, results reveal that the residents of municipalities hit by import shocks are more likely to perceive integration with China as a risk to Brazil. This finding is robust across model specifications. Export shocks produce no equivalent effect, though; residents in areas that benefited from export shocks do not find ties with China any more as an opportunity than those living in unaffected localities.

When expressed as average marginal effects, we observe that a unit increase in import shocks per worker increases the chances that an individual views China more as a risk than as an opportunity. The probability of strongly agreeing or agreeing that China is a risk rather than an opportunity is 18 percent when the shock per worker is US$ 266, the national average, and grows to 25 percent when the impact is US$ 1,220, the top decile, and 33 percent when the impact is US$ 2,140, the maximum observed in the sample. Equivalent average marginal effects for export shocks do not present statistically significant effects (Figure 13.3). Figure 13.A.2 in the Appendix expresses findings as predicted probabilities from the logistic models.

These results highlight an asymmetry in the responses to China among residents in regions that have either benefited or been adversely affected by Chinese trade. We posit that these divergent reactions are likely influenced by the information disseminated by individuals working directly in sectors exposed to Chinese markets and competition. Our hypothesis is that individuals employed in companies directly impacted by Chinese competition are cognizant of China’s role in their losses, whereas those working in businesses benefiting from Chinese imports may not readily associate those benefits with China.

One way to test this hypothesis is by examining how business associations that represent companies that are winners and losers from Chinese trade refer to China. The National Industry Confederation (CNI) and the National Confederation of Agriculture offer an interesting illustration of the same asymmetries observed among residents of localities benefited and harmed by Chinese trade.

Articles posted on the CNI website, in reference to China, frequently mention Chinese protectionism, complain about the low value added of Brazilian exports to China, defend subsidies for Chinese products, and point to Chinese unfair competition in Latin America, among other negative topics. Many suggest that Brazil should not recognize China as a market economy (Urdinez and Masiero Reference Urdinez and Masiero2015). The website of the National Confederation of Agriculture (CNA), conversely, often refers to China altogether along with other Asian markets, and rarely credits the boom experienced by Brazilian agribusiness to the country, but to the “competitiveness of Brazilian producers.”

We can also observe those different responses to China in local news. It is easy to find newspaper articles citing industries hurt by what is often depicted as Chinese “unfair competition.” “Ball made in China thrashes in price and knocks down competition in Brazil,”Footnote 8 “Chinese competition swallows markets for Brazilian products,”Footnote 9 “Fashion pole, Prado neighborhood, suffers from Chinese competition,”Footnote 10 “Competition with garlic from China affects income of 12,000 producer families,”Footnote 11 “Invasion of Chinese products closes industries in Brazil,”Footnote 12 “Chinese competition worries the Capixaban printing industry.”Footnote 13

These examples suggest that residents of localities heavily affected by Chinese competition have elements to blame the country for their economic decay. We found no equivalent of such news associating the success of commodity producers to China.

13.3 Why Are Winners Apparently Indifferent to China?

The asymmetry of responses between winners and losers from trade is not new to the literature. Studies on lobbying traditionally assume that special interest groups (SIGs) who spend the most effort on lobbying and other political activities should be the ones to get the most government support. This contrasts, however, with the so-called losers’ paradox – the disproportionate support losing industries receive relative to winning ones (Hufbauer and Rosen Reference Hufbauer and Rosen1986; Hufbauer et al. Reference Hufbauer and Rosen1986; Ray Reference Ray and Greenaway1991). After all, lobbying to reverse losses and lobbying to secure new gains should be equally attractive to interest groups.

Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud (Reference Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud2007, 1064) suggest that the explanation for this puzzle relies on the so-called NIMBY (not in my backyard) syndrome. Consistent with prospect theory’s claim that losses loom larger than equivalent gains (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Jervis Reference Jervis1992), special interest groups seem to fight harder to avoid losses than they do to achieve benefits from government in trade-related activities.

Mayda and Rodrik (Reference Mayda and Rodrik2005) note this same asymmetry in individual support for protectionism. Based on large-N survey data from several developed and developing countries, they conclude that individuals employed in import-competing industries are more likely to favor trade restrictions, compared to those that work in non-trade sectors. Individuals employed in export-oriented sectors, however, are not significantly less predisposed to trade restrictions.

The tendency to blame competitors for negative import shocks while ignoring the role of trade partners in fostering favorable export shocks is also in line with what psychologists label the “self-serving bias” – the human tendency to blame others for losses, while taking credit for gains (Shepperd et al. Reference Shepperd, Malone and Sweeny2008; Larsen Reference Larsen2021).

It should not be surprising, thus, that individuals are more sensitive to the losses caused by Chinese competition – business closures, neighbors, and family job losses – than to the benefits brought by the expansion of the Chinese market. We should not be surprised, either, that losers blame China for their losses, whereas winners fail to recognize the relevance of the expansion of Chinese markets to the prosperity they have enjoyed since the early 2000s.

In addition to self-serving bias and the asymmetric effects of losses relative to gains, some characteristics of the Brazilian commodity market help explain players’ indifference toward China. Brazilian exports of agribusiness goods amount to US$84.9 billion, with the Chinese market representing 34 percent. This share reaches 79 percent in the case of soybeans, almost twice the share of chemical wood pulp (39 percent) and meat of bovine animals (47 percent) (Li et al. Reference Li, Zhou, Kou C, Nonnemberg, Lima, Bispo, Araújo and Pedrosa2022). Specialists estimate there are 243,000 soy producers in Brazil, and that the soy supply chain generated around 1.4 million jobs.

Given the significant dependence of soy exports on the Chinese market, one might reasonably anticipate that soy producers would be among China’s most fervent advocates in Brazil. Interestingly, we find no evidence in support of that. There are hardly any references to China on the websites of any of the APROSOJAs (the Brazilian state and national associations of soy producers), and none of these associations publicly repudiated anti-China declarations from the Bolsonaro administration.

On the contrary, the APROSOJAs frequently aligned with producers of other grains, predominantly corn, and beef, in support of Bolsonaro, seemingly unconcerned about his adversarial stance toward China. During the presidential campaign of 2022, the state of Minas Gerais branch of APROSOJA (APROSOJA-MG) released an open letter in support of the re-election of President Bolsonaro. The letter invited farmers, ranchers, and rural workers, that is, the entire productive sector, to work together “day and night” to support the re-election of President Bolsonaro, in their words a president “aligned with the wishes of the productive sector.”

We conjecture that the low levels of vertical integration in the soybean market help explain this paradox. Brazilian producers sell their grains to storage units, which can be cooperatives and state and public companies. They also sell to industrial companies, which will produce soybean meal, crude, and refined oil, or directly to big trading companies such as the American multinationals ADM, Bunge and Cargill, the Chinese Cofco, or the Brazilian Amaggi, among others. As in any commodities market, prices are set internationally.

This structure implies that producers are distant from their end markets, having poor information about the impact of Chinese markets on prices and, therefore, their performance. Many producers do not even know that China is their main consumer market or has an office in the country. It was only in 2020 that the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture opened a Chinese division. It is not surprising, thus, that soy-producing associations ignored when the Foreign Relations Minister Ernesto Araujo attributed the responsibility for the coronavirus pandemic to China and compared Chinese lockdowns to Nazi camps.

In fact, the only public defense of Brazil-China relations came from Mr. Blairo Maggi – dubbed “the soy king” – a former Minister of Agriculture, senator, and governor of the State of Mato Grosso, whose family owns Amaggi. Different from other soy producers, Amaggi operates in all stages of the agribusiness supply chain, including logistics and exports of agricultural commodities like soy and corn. The company owns soybean crushing and fertilizer blending factories, manages small hydropower plants (SHPs), and invests in photovoltaic power plants to harness solar energy in its main farms and warehouses. As such, unlike other companies that distribute their soy through intermediaries, Amaggi directly engages with importing markets. Consequently, its management, and most probably its employees, possesses a deep understanding of the pivotal role that the Chinese market plays within the Brazilian commodity sector.

We devise a few strategies to test the hypothesis that lack of vertical integration is what prevents employees in soy-producing firms – and, ultimately, residents of soy-producing municipalities – from realizing the benefits they accrue from Chinese markets. The first strategy is by comparing differences in approaches to China among associations that represent soy producers, such as the APROSOJAs, vis-à-vis associations that represent the soy industry, more exposed to end markets. An example would be the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries (ABIOVE).

An alternative test of this hypothesis could be to compare the APROSOJAs with associations that represent more vertically integrated sectors like meat, such as the Brazilian Association of the Brazilian Association of Animal Protein (ABPA). We plan to explore this hypothesis in future research.

13.4 Conclusion

This chapter examined whether localized import and export shocks associated with growing trade with China affect Brazilians’ views about economic integration with the country. The analyses presented leveraged a recently published dataset that calculates import and export shocks from China, per worker, at the municipal level in Brazil (Costa et al. Reference Costa, Garred and Pessoa2016). Thanks to a commodity-for-manufacture pattern of trade between the two countries, along with the fact that both industry and agribusiness activities are geographically concentrated in Brazil, the distribution of trade shocks is highly skewed in the country. This implies that few localities experience strong shocks, whereas the majority are unaffected.

The main argument advanced in the study was that when trade shocks are localized, attitudes about trade and trade partners should respond to income shocks that occur at the local level. As such, responses to these shocks should not be restricted to those employed in losing industries but rather spread to other residents working in the service sector in the same locality.

The chapter presented the results of a national survey aimed to test whether income shocks related to international trade influenced residents’ views of Brazilian ties with China. It tested the hypothesis that those who live in localities hit by import (export) shocks should see ties with China as posing predominantly a risk (opportunity) to Brazil.

Results offered support for these hypotheses but only among losers from Chinese trade; import shocks affected residents’ assessments of China, while export shocks did not. Sectors of employment did not affect responses under any specification, either independently or as a moderator of the impact of shocks.

We discussed how the results align with prospect theory’s idea that losses have a stronger impact than equivalent gains (Kahneman and Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979; Jervis Reference Jervis1992). Additionally, we highlighted previous research indicating that special interest groups are more motivated to avoid losses rather than pursue benefits in government-related trade activities.

We also suggested that the structure of the Brazilian commodity sector can help explain why winners of Chinese trade seemed indifferent to their main market. Taking soy as an example, we argued that limited vertical integration separates producers from their end markets, leaving them unaware of the influence of the Chinese markets on prices and their own performance.

Ultimately, these findings extend the research on losers of globalization beyond the developed world, which so far received most of the attention in the literature. They suggest that, in countries where mechanisms of compensation are known to be scarce, asymmetric responses to losses from trade may be a potential driver of the backlash against globalization.