Introduction

Globally, one in eight individuals lives with a mental disorder, with anxiety and depressive disorders being the most common(1). As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people who experience anxiety and depressive illnesses has significantly increased(1,2) . Appropriate treatments and interventions are difficult to access owing to high demand, highlighting the need for new, effective interventions to reduce the disease burden.

Psychotherapy, medications and lifestyle modifications are the primary treatments for mental disorders(Reference Hirschfeld3,Reference Velten, Bieda, Scholten, Wannemuller and Margraf4) . Mood disorders are chronic and often require lifelong treatment. Long-term antidepressant therapy is typically necessary for depression, however, up to 50% of individuals with depression may experience adverse effects or inadequate response to initial antidepressant treatments(Reference Hirschfeld3). As a result, there is a growing interest in safe, low-cost and non-pharmacological preventive and therapeutic options. Lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity and sleep have been linked to the onset and symptoms of various mental illnesses(Reference Xu, Anderson and Courtney5–Reference Mikkelsen, Stojanovska, Prakash and Apostolopoulos8). Specifically, the relationship between diet and mental illnesses, particularly in depressive disorders, has gained significant attention in recent years. However, many studies have focused on the consumption of individual nutrients or food groups rather than considering overall dietary patterns or styles(Reference Tolmunen, Hintikka, Ruusunen, Voutilainen, Tanskanen and Valkonen9,Reference Murakami, Mizoue, Sasaki, Ohta, Sato and Matsushita10) . Although scarce, there are previous studies that tried to assess the relationship between Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) patterns and mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety(Reference Jacka, O’Neil, Opie, Itsiopoulos, Cotton and Mohebbi11–Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Martinez-Gonzalez, Estruch, Salas-Salvado, Corella and Covas13). The term ‘depression’ refers to both depressive symptoms and clinical diagnosis in this review.

The MedDiet is a traditional diet characterised by high intake of plant foods (fruit, vegetables, cereals, nuts and legumes); fermented dairy foods (principally yoghurt and cheese); considerable use of extra virgin olive oil as the main source of fat; low-to-moderate consumption of fish, poultry and eggs; low intake of red meat; and moderate wine consumption(Reference Willett, Sacks, Trichopoulou, Drescher, Ferro-Luzzi and Helsing14). This largely plant-based dietary pattern encourages the intake of seasonal and local produce. In addition, the MedDiet is known for its high-quality fat content, mainly of plant origin (such as olive oil and nuts); healthy fats in the MedDiet make it more palatable and widely acceptable, as evidenced by many studies across various population groups(Reference Murphy and Parletta15–Reference Estrada Del Campo, Cubillos, Vu, Aguirre, Reuland and Keyserling17).

There are several methods to define a dietary pattern or style including general descriptions, dietary pyramids, a priori scoring systems, a posteriori dietary pattern formations or by food and nutrient content(Reference Willett, Sacks, Trichopoulou, Drescher, Ferro-Luzzi and Helsing14,Reference Bach-Faig, Berry, Lairon, Reguant, Trichopoulou and Dernini18–Reference Saura-Calixto and Goni20) . Of these, a priori scoring systems are the most popular as they simplify the analysis of adherence to a diet in relation to primary outcomes.(Reference Sofi, Macchi, Abbate, Gensini and Casini21) A commonly utilised score of the MedDiet is the MedDiet score (MDS)(Reference Hutchins-Wiese, Bales and Porter Starr22), which includes nine components. One point is assigned for intakes of each ‘healthy foods’ above the sex-specific median (vegetables, fruits/nuts, legumes, fish/seafood, cereals and the monounsaturated to saturated lipid ratio) and one point each is assigned for intakes below median for meat and dairy products; for alcoholic beverages, one point is assigned for moderate intake(Reference Trichopoulou, Kouris-Blazos, Wahlqvist, Gnardellis, Lagiou and Polychronopoulos19).

There have been consistent reports of the health benefits of the MedDiet for several diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity and certain types of cancers, as well as for mental health(Reference Dinu, Pagliai, Casini and Sofi23–Reference Ventriglio, Sancassiani, Contu, Latorre, Di Slavatore and Fornaro25). Moreover, individual foods and components of the MedDiet (e.g. extra-virgin olive oil and nuts) have well-documented health benefits, but in recent years special attention has been given to the overall combination of foods, expressed as a MedDiet dietary pattern, which is strongly related to health likely owing to the synergistic effects of different components(Reference Gaforio, Visioli, Alarcon-de-la-Lastra, Castaner, Delgado-Rodriguez and Fito26,Reference Ros27) .

Previous reviews assessing the link between MedDiet and mental health lack comprehensiveness, where the majority of studies primarily focus on depression rather than overall mental health(Reference Altuna, Brown, Szoekea and Goodwilla28,Reference Eliby, Simpson, Lawrence, Schwartz, Haslam and Simmons29) . In addition, studies fail to address the underlying mechanisms by which the MedDiet might impact mental health(Reference Ventriglio, Sancassiani, Contu, Latorre, Di Slavatore and Fornaro25). Therefore, we aimed to systematically review the evidence for an effect of MedDiet on mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, stress, mental wellbeing and quality of life, as well as summarise the possible underlying mechanisms of action to complement the systematic review findings.

Methods

Study protocol and registration

A protocol for this review was registered a priori on Open Science Framework (OSF) (registration: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/E5ZSB). The reporting of this review followed the PRISMA statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews(Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow30) (Supplementary File 2).

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, CINAHL and Embase up to July 2025. The following keywords were used in the primary searches: ‘Mediterranean diet’ OR ‘Mediterranean lifestyle’ OR ‘Mediterranean-lifestyle’ OR ‘Mediterranean life-style’ OR ‘Mediterranean eating’ OR ‘Mediterranean dish’ OR ‘Diet, Mediterranean’ AND ‘stress’ OR ‘anxiety’ OR ‘anxi*’ OR ‘depress*’ OR ‘distress*’ OR ‘happiness’ OR ‘mental health’ OR ‘mood’ OR ‘psychological disorder’ OR ‘psycholog*’ OR ‘wellbeing’ OR ‘well-being’ OR ‘wellness’ OR ‘health’ OR ‘quality of life’ OR ‘mental state’ OR ‘Psychological Well-Being’ OR ‘mood disorder’ OR ‘anxiety disorder’.

Broad search terms were used intentionally to capture the maximum number of relevant articles. There were no limits in terms of study settings and time frame. In addition, a manual search of reference lists of included studies was performed to identify additional studies which may have been missed. In this review we tried to capture all the MedDiet scores and MedDiet adherence measurement scales (Supplementary File 1).

Study selection

Inclusion criteria: (1) all study designs, (2) articles written in the English language, (3) no limit on date of publication, (4) studies conducted on adults and (5) only studies that investigated the effect of the MedDiet on depression, anxiety, stress, mental wellbeing and quality of life were eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria: (1) incomplete reporting of the main results, including the study’s outcomes; (2) grey literature, non-peer-reviewed publications and conference abstracts; (3) inadequate or otherwise incomplete methods reporting (i.e. vague/incomplete/inadequate details of definitions, samples, materials and/or procedures.

Review management software (Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/), Veritas Health Innovation Ltd.) was used to manage searches and subsequent screening. Following the removal of duplicated papers, title and abstract screening was performed for all the identified studies by two independent reviewers (R.K. and J.F.), and a full-text review was then performed.

Descriptive information was extracted from all articles, including authors and year of publication, study design, study method, population and an intervention/exposure description, key findings and outcomes measured.

Quality assessment: the quality of all included studies in this review was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist(Reference Munn, Stone, Aromataris, Klugar, Sears and Leonardi-Bee31) for cross-sectional analyses, cohort studies, case–control and randomised controlled trials. The JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist was used because it offers tailored tools for various study designs essential in nutrition research (with its methodological diversity), while comprehensively assessing internal validity, risk of bias and the appropriateness of study conduct and reporting. The quality assessment was used to help evaluate the quality of evidence but not to exclude any studies. The primary researcher completed the assessment.

Findings

Study selection

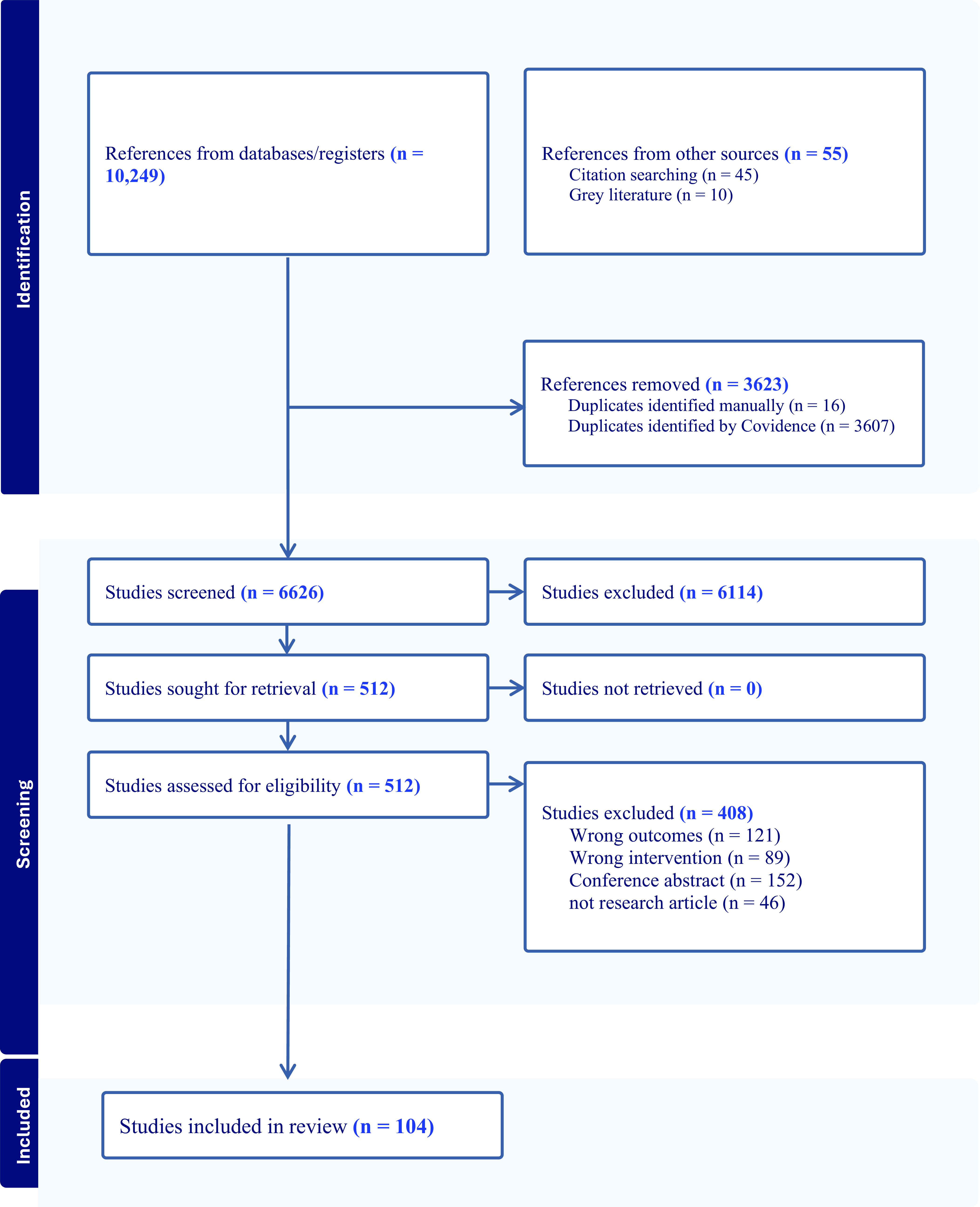

The process of study selection is shown in Fig. 1. The primary literature search yielded 10 249 studies, and an additional 55 were identified in the updated search. A total of 3623 duplicates were removed, and 6626 articles were assessed by title and abstract. Of these, 512 were eligible for full-text review, of which 408 records were excluded. Thus, a total of 104 studies were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram of the screening and selection process for this narrative review on the effect of the Mediterranean diet on mental health.

The majority of the studies included are cross sectional (n = 63), followed by cohort studies (n = 24), randomised controlled trials (n = 16) and case–control studies (n = 1).

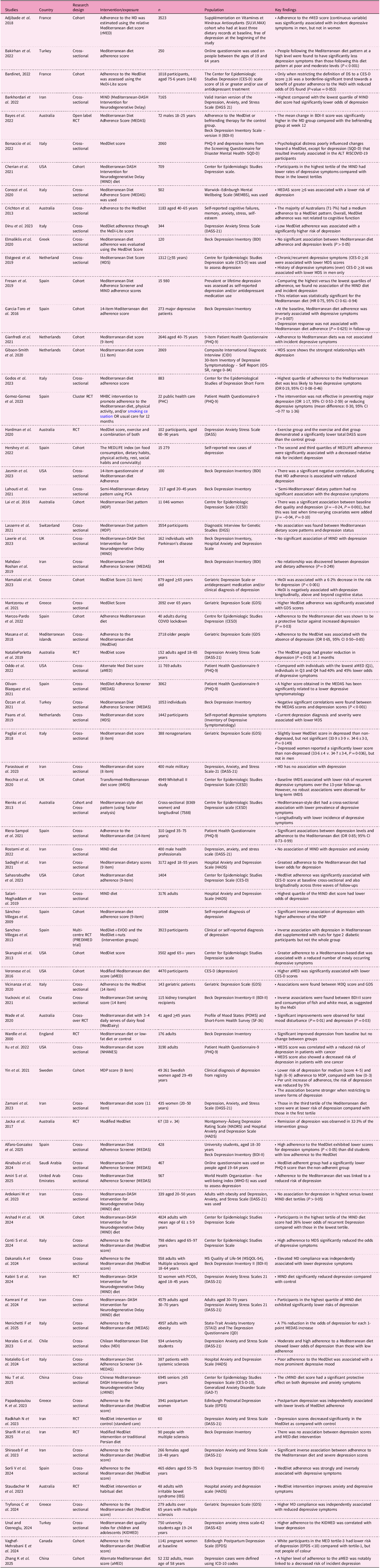

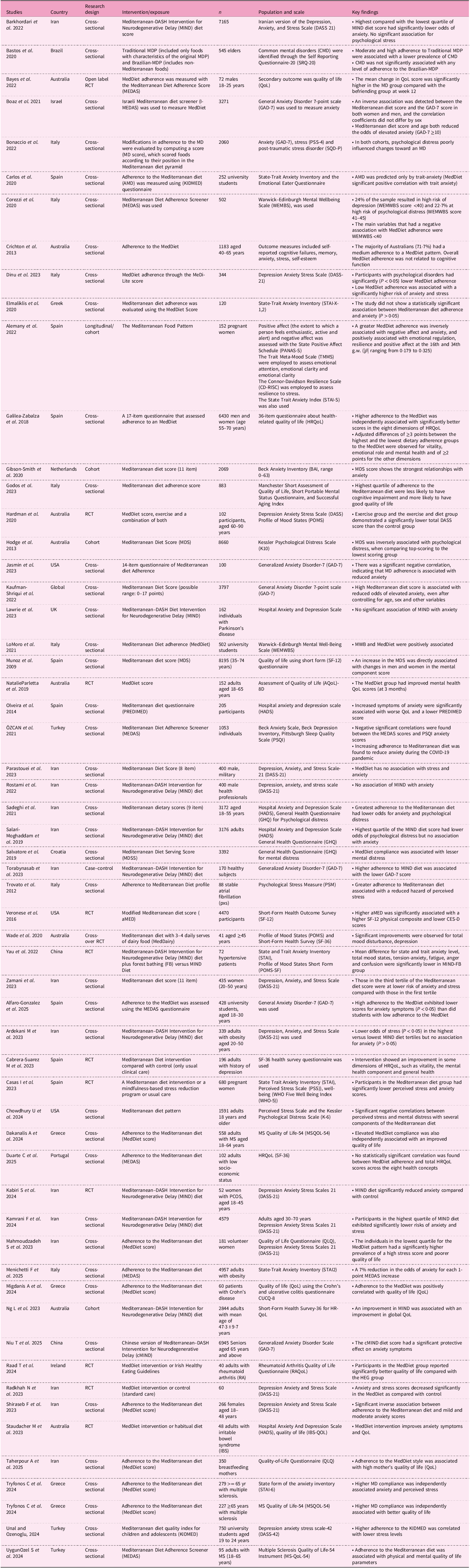

The included studies were conducted across twenty-two different countries, with two additional studies involving participants from multiple countries. Iran and Spain contributed the highest number of studies (n = 16 each), followed by Australia (n = 12), Italy (n = 11), Greece (n = 9), USA (n = 8), Turkey (n = 5), the UK (n = 4), China (n = 3), the Netherlands (n = 3), Croatia (n = 2), France (n = 2), Ireland (n = 2) and one study each from Chile, Brazil, Israel, Canada, Switzerland, Sweden, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Portugal. The ages of the participants varied widely, ranging from 18 to 97 years, reflecting a broad representation across the adult lifespan(Reference Alfaro-Gonzalez, Garrido-Miguel, Pascual-Morena, Pozuelo-Carrascosa, Fernandez-Rodriguez and Martinez-Hortelano32,Reference Conti, Perdixi, Bernini, Jesuthasan, Severgnini and Prinelli33) . The majority of studies included participants from the general population who exhibited depressive symptoms but did not necessarily have a formal clinical diagnosis. Only a limited number of studies used clinical diagnosis as the primary outcome measure(Reference Jacka, O’Neil, Opie, Itsiopoulos, Cotton and Mohebbi11–Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Martinez-Gonzalez, Estruch, Salas-Salvado, Corella and Covas13,Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt34–Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Delgado-Rodriguez, Alonso, Schlatter, Lahortiga and Serra Majem38) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Summary of findings on the role of MedDiet on depression

Table 2 Anxiety, stress, psychological wellbeing and quality of life

Quality of studies

Generally, the quality of cross-sectional studies met ≥75% of the criteria for almost all of the included studies. However, failure to use appropriate statistical analyses was noted(Reference Jasmin, Fusco and Petrosky39–Reference Migdanis, Migdanis, Gkogkou, Papadopoulou, Giaginis and Manouras41). All cohort, case–control and randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies showed good overall quality, meeting ≥75% of the criteria. In the RCT studies, masking of the dietary intervention was not possible owing to the nature of the intervention, hence, all of the studies were open label RCTs (Supplementary File 3).

Tools used for assessment of the Mediterranean diet

Although diverse definitions and scoring tools were used to assess adherence to the MedDiet across studies, a relatively consistent inverse association with depression was observed(Reference Adjibade, Assmann, Andreeva, Lemogne, Hercberg and Galan42–Reference Bakırhan, Pehlivan, Özyürek, Özkaya and Yousefirad44), suggesting that core dietary components characteristic of the MedDiet may drive these beneficial effects. Some of the scoring and definitions used include MedDiet score(Reference Adjibade, Assmann, Andreeva, Lemogne, Hercberg and Galan42,Reference Bardinet, Chuy, Carriere, Galera, Pouchieu and Samieri43,Reference Elmaliklis, Miserli, Filipatou, Tsikouras, Dimou and Koutelidakis45,Reference Elstgeest, Winkens, Penninx, Brouwer and Visser46) , alternative MedDiet (aMed)(Reference Veronese, Stubbs, Noale, Solmi, Luchini and Maggi47), MedDiet pattern(Reference Bakırhan, Pehlivan, Özyürek, Özkaya and Yousefirad44), Medi Lite(Reference Dinu, Lotti, Napoletano, Corrao, Pagliai and Tristan Asensi48), Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND),(Reference Barkhordari, Namayandeh, Mirzaei, Sohouli and Hosseinzadeh49–Reference Fresan, Bes-Rastrollo, Segovia-Siapco, Sanchez-Villegas, Lahortiga and de la Rosa51) MedDiet adherence score (MEDAS)(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt34) and MedDiet supplemented with various food items (Modified Med diet)(Reference Jacka, O’Neil, Opie, Itsiopoulos, Cotton and Mohebbi11,Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Martinez-Gonzalez, Estruch, Salas-Salvado, Corella and Covas13) . Modified versions of the MedDiet, such as the MIND diet and locally adapted scoring systems such as the Brazilian MedDiet pattern(Reference Bastos, Nogueira, Neto, Fisberg, Yannakoulia and Ribeiro52) and the Israeli MedDiet screener (I-MEDAS)(Reference Boaz, Navarro, Raz and Kaufman-Shriqui53) have also been employed in several studies investigating the association between the MedDiet and mental health outcomes.

Depression

The link between depression and the MedDiet has been reported by various authors in diverse study settings and geographical locations (Table 1).

Observational studies

Cross-sectional and cohort studies have predominantly been used to assess the relationship between MedDiet and depression. There are mixed results from cross-sectional studies, with a majority highlighting that a high MedDiet score is associated with a reduction of depressive symptoms in a range of populations.

Several studies assessing cross-sectional associations between adherence to a MedDiet and depressive symptoms found that higher adherence was associated with fewer depressive symptoms(Reference Alfaro-Gonzalez, Garrido-Miguel, Pascual-Morena, Pozuelo-Carrascosa, Fernandez-Rodriguez and Martinez-Hortelano32,Reference Conti, Perdixi, Bernini, Jesuthasan, Severgnini and Prinelli33,Reference Jasmin, Fusco and Petrosky39,Reference Bakırhan, Pehlivan, Özyürek, Özkaya and Yousefirad44,Reference Dinu, Lotti, Napoletano, Corrao, Pagliai and Tristan Asensi48,Reference Sahasrabudhe, Soo Lee, Zhang, Scott, Punnett and Tucker54–Reference Sadeghi, Keshteli, Afshar, Esmaillzadeh and Adibi73) . Similarly, some studies reported that poor adherence to the MedDiet was linked with more pronounced depressive symptoms(Reference Natalello, Bosello, Campochiaro, Abignano, De Santis and Ferlito74,Reference Papadopoulou, Pavlidou, Dakanalis, Antasouras, Vorvolakos and Mentzelou75) . In contrast, other studies found no significant association between MedDiet adherence and depressive symptom(Reference Elmaliklis, Liveri, Ntelis, Paraskeva, Goulis and Koutelidakis40,Reference Elmaliklis, Miserli, Filipatou, Tsikouras, Dimou and Koutelidakis45,Reference Ardekani, Vahdat, Hojati, Moradi, Tousi and Ebrahimzadeh76,Reference Mahdavi-Roshan, Salari, Ashouri and Alizadeh77) . Twenty-seven out of thirty-one studies reported statistically significant associations, while four studies found no association between the MedDiet and depressive symptoms.

Studies reported strong longitudinal associations between higher MedDiet scores and a reduced risk of both depression and recurrent depressive episodes despite the use of diverse tools to assess diet adherence and depressive symptoms(Reference Gibson-Smith, Bot, Brouwer, Visser, Giltay and Penninx36,Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Delgado-Rodriguez, Alonso, Schlatter, Lahortiga and Serra Majem38,Reference Adjibade, Assmann, Andreeva, Lemogne, Hercberg and Galan42,Reference Cherian, Wang, Holland, Agarwal, Aggarwal and Morris50,Reference Sahasrabudhe, Soo Lee, Zhang, Scott, Punnett and Tucker54,Reference Hershey, Sanchez-Villegas, Sotos-Prieto, Fernandez-Montero, Pano and Lahortiga-Ramos78–Reference Lugon, Hernaez, Jacka, Marrugat, Ramos and Garre-Olmo86) . In addition, individual food components characteristic of the MedDiet have been independently associated with lower levels of depression. Specifically, higher daily consumption of vegetables, fruits, olive oil and traditional sauces containing olive oil, tomato and garlic was linked to reduced depressive symptoms(Reference Bakırhan, Pehlivan, Özyürek, Özkaya and Yousefirad44). All fifteen cohort studies reported a significant association of MedDiet with reduced depressive symptoms.

Interventional studies

Nine out of eleven interventional studies reported a significant reduction in depressive symptoms, while two studies reported no significant changes in depressive symptoms. Compared with alternative or usual dietary patterns, MedDiet interventions were associated with reductions in depressive symptoms(Reference Parletta, Zarnowiecki, Cho, Wilson, Bogomolova and Villani12,Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt34,Reference Veronese, Stubbs, Noale, Solmi, Luchini and Maggi47) . While significant within-group improvements were observed from baseline in some MedDiet intervention groups, these changes were not always statistically significant when compared with control groups(Reference Wardle, Rogers, Judd, Taylor, Rapoport and Green87). In addition, an intervention combining the MedDiet with exercise demonstrated greater reductions in depressive symptoms in the intervention group relative to the control group(Reference Hardman, Meyer, Kennedy, Macpherson, Scholey and Pipingas88).

The multi-centre PREDIMED trial compared a low-fat diet with two enhanced MedDiets (MedDiet plus extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) and MedDiet plus nuts). No significant reduction in depressive symptoms was observed in both groups. However, when the samples were restricted to those with type 2 diabetes, a significant reduction in the incidence of depression, diagnosed by physicians, was noted in the MedDiet supplemented with nuts group(Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Martinez-Gonzalez, Estruch, Salas-Salvado, Corella and Covas13).

Beyond depression prevention, the SMILES trial demonstrated remission of depression through a MedDiet intervention. This trial compared a modified MedDiet based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines and the Dietary Guidelines for Adults in Greece with a befriending social support control, where trained personnel engaged participants with neutral topics such as sports, news or music. Among individuals with clinical depression, the intervention group experienced a significant reduction in depressive symptoms compared with controls, with approximately one-third achieving remission(Reference Jacka, O’Neil, Opie, Itsiopoulos, Cotton and Mohebbi11).

Compared with standard care, MedDiet interventions have been shown to significantly reduce depression scores(Reference Radkhah, Rasouli, Majnouni, Eskandari and Parastouei89). Specifically, individuals with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) experienced reduced depressive symptoms when following a MedDiet compared with a control diet(Reference Kabiri, Javanbakht, Zangeneh, Moludi, Saber and Salimi90). However, in participants with multiple sclerosis, the MedDiet did not lead to a significant reduction in depression scores when compared with a traditional Persian diet, suggesting possible condition-specific differences in responses(Reference Sharifi, Poursadeghfard, Afshari, Alizadeh, Vatanpour and Soltani91). In addition, among individuals with irritable bowel syndrome, adherence to a MedDiet resulted in a notable decrease in depressive symptoms compared with their habitual dietary patterns(Reference Staudacher, Mahoney, Canale, Opie, Loughman and So92). These findings highlight the potential mental health benefits of the MedDiet across various clinical populations, while also indicating the need for further research on its efficacy in different health conditions.

Anxiety

Observational findings

Strong inverse cross-sectional associations between MedDiet scores and anxiety were observed in a significant number of studies(Reference Alfaro-Gonzalez, Garrido-Miguel, Pascual-Morena, Pozuelo-Carrascosa, Fernandez-Rodriguez and Martinez-Hortelano32,Reference Jasmin, Fusco and Petrosky39,Reference Dinu, Lotti, Napoletano, Corrao, Pagliai and Tristan Asensi48,Reference Barkhordari, Namayandeh, Mirzaei, Sohouli and Hosseinzadeh49,Reference Boaz, Navarro, Raz and Kaufman-Shriqui53,Reference Özcan, Yeşilkaya, Yilmaz, Günal and Özdemir60,Reference Kamrani, Kachouei, Sobhani and Khosravi64,Reference Menichetti, Battezzati, Bertoli, De Amicis, Foppiani and Sileo65,Reference Niu, Zhang, Zhou, Shen, Ji and Zhu67,Reference Shiraseb, Mirzababaei, Daneshzad, Khosravinia, Clark and Mirzaei68,Reference Tryfonos, Pavlidou, Vorvolakos, Alexatou, Vadikolias and Mentzelou70,Reference Sadeghi, Keshteli, Afshar, Esmaillzadeh and Adibi73,Reference Carlos, Elena and Teresa93–Reference Zamani, Zeinalabedini, Nasli Esfahani and Azadbakht96) , whilst others reported no association(Reference Elmaliklis, Miserli, Filipatou, Tsikouras, Dimou and Koutelidakis45,Reference Ardekani, Vahdat, Hojati, Moradi, Tousi and Ebrahimzadeh76,Reference Lawrie, Coe, Mansoubi, Welch, Razzaque and Hu97–Reference Salari-Moghaddam, Keshteli, Mousavi, Afshar, Esmaillzadeh and Adibi100) (Table 2). Sixteen out of twenty-two cross-sectional studies show association of a MedDiet with reduced anxiety symptoms, while six studies reported no association.

A case–control study by Torabynasab et al. reported that a higher adherence to the Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet was associated with lower generalised anxiety disorder (GAD-7) scores(Reference Torabynasab, Shahinfar, Jazayeri, Effatpanah, Azadbakht and Abolghasemi101). In addition, data from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) demonstrated a strong association between higher MedDiet scores and reduced anxiety symptoms, as measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)(Reference Gibson-Smith, Bot, Brouwer, Visser, Giltay and Penninx36).

Interventional studies

Four of the five interventional studies reported a reduction in anxiety symptoms following a MedDiet intervention(Reference Radkhah, Rasouli, Majnouni, Eskandari and Parastouei89,Reference Kabiri, Javanbakht, Zangeneh, Moludi, Saber and Salimi90,Reference Staudacher, Mahoney, Canale, Opie, Loughman and So92,Reference Casas, Nakaki, Pascal, Castro-Barquero, Youssef and Genero102) , whereas one study found no significant change(Reference Yau, Law and Wong103). A three-arm randomised controlled trial comparing MedDiet plus forest bathing, MedDiet alone and a control group found a significant reduction in anxiety scores, as measured by the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), in the MedDiet plus forest bathing group compared with the control group. However, no significant difference in anxiety scores was observed between the MedDiet alone group and the control group(Reference Yau, Law and Wong103). A MedDiet intervention significantly reduced anxiety levels among pregnant women compared with usual care(Reference Casas, Nakaki, Pascal, Castro-Barquero, Youssef and Genero102). Similarly, a MedDiet led to lower anxiety scores when compared with standard care(Reference Radkhah, Rasouli, Majnouni, Eskandari and Parastouei89). In addition, a MedDiet intervention, relative to a control diet, resulted in reduced anxiety symptoms in individuals with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)(Reference Kabiri, Javanbakht, Zangeneh, Moludi, Saber and Salimi90). Furthermore, among individuals with irritable bowel syndrome, adherence to a MedDiet was associated with a greater reduction in anxiety symptoms compared with those following their habitual diet(Reference Staudacher, Mahoney, Canale, Opie, Loughman and So92). These findings collectively suggest that the MedDiet may offer meaningful benefits in reducing anxiety across diverse populations, supporting its potential role as a complementary strategy in managing anxiety-related symptoms (Table 2).

Quality of life (QoL)

Eight out of nine cross-sectional studies reported a significant association of MedDiet with improved quality of life (QoL), while one study reported no association. In studies examining cross-sectional associations, higher adherence to the MedDiet was independently associated with significantly improved quality of life scores compared with low-adherence groups(Reference Migdanis, Migdanis, Gkogkou, Papadopoulou, Giaginis and Manouras41,Reference Godos, Grosso, Ferri, Caraci, Lanza and Al-Qahtani55,Reference Dakanalis, Tryfonos, Pavlidou, Vadikolias, Papadopoulou and Alexatou63,Reference Galilea-Zabalza, Buil-Cosiales, Salas-Salvado, Toledo, Ortega-Azorin and Diez-Espino104–Reference Uygun Ozel, Bayram and Kilinc107) . Similarly, another study found that individuals in the lowest quartile of adherence to the MedDiet diet pattern were significantly more likely to experience poorer quality of life(Reference Sara Mahmoudzadeh, Khorasanchi, Karbasi, Ferns and Bahrami108), highlighting the potential impact of dietary habits on overall wellbeing. However, another cross-sectional study reported no significant association between MedDiet adherence and health related QoL(Reference Duarte, Campos, Pereira and Lima109).

Cohort studies examining the longitudinal association between MedDiet adherence and quality of life reported significant improvements in overall QoL(Reference Ng, Hart, Dingle, Milte, Livingstone and Shaw110), as well as in specific subdomains such as the physical composite score of QoL(Reference Veronese, Stubbs, Noale, Solmi, Luchini and Maggi47).

All five interventional studies assessing the effect of a MedDiet reported a significantly improved quality of life. A randomised controlled trial evaluating the impact of a MedDiet intervention, comprising food hampers and cooking workshops, reported a significant improvement in mental-health-related quality of life among participants in the MedDiet group compared with those in the control group, who attended social gatherings(Reference Parletta, Zarnowiecki, Cho, Wilson, Bogomolova and Villani12). In addition, MedDiet interventions led to improvements in health-related quality of life compared with usual care(Reference Cabrera-Suarez, Lahortiga-Ramos, Sayon-Orea, Hernandez-Fleta, Gonzalez-Pinto and Molero35). Another randomised trial found that a MedDiet intervention produced greater improvements in quality of life than the Irish healthy eating guidelines among participants with rheumatoid arthritis(Reference Raad, George, Griffin, Larkin, Fraser and Kennedy111). Similarly, in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome, adherence to a MedDiet was associated with improved quality of life compared with those following their habitual diet(Reference Staudacher, Mahoney, Canale, Opie, Loughman and So92). Furthermore, a 12-week randomised controlled trial in young males demonstrated that adherence to a MedDiet significantly improved overall quality of life compared with the control group(Reference Bayes, Schloss and Sibbritt34).

Taken together, these findings consistently support the beneficial impact of the MedDiet on health-related quality of life across a range of populations and health conditions, further highlighting its potential as a complementary approach in health promotion and disease management (Table 2).

Stress and mental wellbeing

All eight cross-sectional studies reported a significant association of MedDiet with reduced stress levels. Higher adherence to the MedDiet, when compared with low adherence, was strongly and inversely associated with psychological distress in cross-sectional analyses(Reference Dinu, Lotti, Napoletano, Corrao, Pagliai and Tristan Asensi48,Reference Kamrani, Kachouei, Sobhani and Khosravi64,Reference Tryfonos, Pavlidou, Vorvolakos, Alexatou, Vadikolias and Mentzelou70,Reference Unal and Ozenoglu71,Reference Sadeghi, Keshteli, Afshar, Esmaillzadeh and Adibi73,Reference Zamani, Zeinalabedini, Nasli Esfahani and Azadbakht96,Reference Salari-Moghaddam, Keshteli, Mousavi, Afshar, Esmaillzadeh and Adibi100) . The individuals in the lowest quartile for the MedDiet pattern had a significantly higher prevalence of a high stress scores(Reference Sara Mahmoudzadeh, Khorasanchi, Karbasi, Ferns and Bahrami108). Similarly, a case–control study by Trovato et al. also reported that a greater adherence to a MedDiet profile is associated with reduced perceived stress, as measured by a psychological stress measure (PSM) test(Reference Trovato, Pace, Cangemi, Martines, Trovato and Catalano112).

All three cohort studies report a significant association of the MedDiet with reduced stress levels. A strong inverse association of the MedDiet with stress was reported in a large longitudinal study(Reference Hodge, Almeida, English, Giles and Flicker113). A MedDiet intervention significantly reduced perceived stress levels among pregnant women when compared with usual care(Reference Casas, Nakaki, Pascal, Castro-Barquero, Youssef and Genero102). Another study also reported a significant inverse association of perceived stress and mental distress with components of the MedDiet(Reference Chowdhury, Bubis, Nagorny, Welch, Rosenberg and Begdache114).

The MedDiet has also been associated with improved mental wellbeing. In a cross-sectional study, a strong positive association was observed between adherence to the MedDiet and mental wellbeing scores, as measured by the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS)(Reference Lo Moro, Corezzi, Bert, Buda, Gualano and Siliquini115). Conversely, two studies reported no significant association between MedDiet adherence and mental wellbeing(Reference Barkhordari, Namayandeh, Mirzaei, Sohouli and Hosseinzadeh49,Reference Parastouei, Rostami and Chambari98) . These mixed findings suggest that, while a MedDiet may support mental wellbeing, further research is needed to clarify the strength and consistency of this relationship (Table 2).

Potential mechanisms

Herein, we provide a narrative overview of the potential mechanisms underlying the relationship between the MedDiet and mental health outcomes to complement and contextualise the findings of this review. The MedDiet has been widely shown to improve mental health outcomes in both apparently healthy individuals and those with diagnosed mental illness. Its beneficial effects are suggested to be mediated through several key mechanisms, including enhanced antioxidant capacity, reduced systemic inflammation and improved gut health(Reference Billingsley and Carbone116–Reference De Filippis, Pellegrini, Vannini, Jeffery, La Storia and Laghi118).

Antioxidant potential of a MedDiet

The health benefits of a MedDiet have often been linked to nutrients with antioxidant potential, which are mostly found in foods such as vegetables, fruits and the characteristic extra virgin olive oil(Reference Trichopoulou, Bamia and Trichopoulos119). Evidence suggests that reactive oxygen species may be a root cause of most chronic diseases, including cardiometabolic and mental diseases(Reference Ames, Shigenaga and Hagen120). Plant-based diets rich in antioxidants have been shown to mitigate some of the negative impacts of reactive oxygen species(Reference Pandey and Rizvi121).

Although the MedDiet is not strictly vegetarian, it is predominantly plant-based and naturally rich in antioxidants(Reference Willett, Sacks, Trichopoulou, Drescher, Ferro-Luzzi and Helsing14). It provides a high intake of micronutrients and bioactive compounds, particularly antioxidant vitamins and polyphenols, largely derived from fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) (Reference Ortega122). Among the key antioxidant vitamins associated with the MedDiet are beta-carotene (a precursor to vitamin A), vitamin C and vitamin E(Reference Castro-Quezada, Roman-Vinas and Serra-Majem123). Dietary antioxidants and polyphenols function as exogenous defenses against oxidative stress and systemic inflammation, two key biological processes implicated in the onset and progression of numerous non-communicable diseases, including mental health disorders such as depression(Reference Pham-Huy, He and Pham-Huy124).

Dietary patterns rich in antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, have been inversely associated with adverse mental health outcomes, including stress(Reference Farhadnejad, Neshatbini Tehrani, Salehpour and Hekmatdoost125). Furthermore, a clinical trial evaluating the effects of antioxidant vitamin supplementation over 6 weeks reported significant reductions in depression and anxiety scores among participants(Reference Gautam, Agrawal, Gautam, Sharma, Gautam and Gautam126). Notably, baseline levels of vitamins A, C and E are significantly lower in individuals with generalised anxiety disorder and depression compared with healthy controls.

Neuron cells in the brain have low levels of endogenous antioxidants to match their high metabolic demand, making it more susceptible to redox imbalance(Reference Cobley, Fiorello and Bailey127). Inflammation and issues in neuronal plasticity, which are associated with depression and anxiety, are common during redox imbalance(Reference Ng, Peters, Ho, Lim and Yeo128,Reference Pereira, da Silva, Hermsdorff, Moreira and de Aguiar129) , making the exogenous dietary antioxidant intake important for mental health. Hence, diets rich in antioxidant nutrients, such as the MedDiet, are critical in enhancing the antioxidant potential of the brain.

Anti-inflammatory potential of the MedDiet

Existing evidence from both observational studies and clinical trials reported the anti-inflammatory effect of the MedDiet(Reference Sood, Feehan, Itsiopoulos, Wilson, Plebanski and Scott130). A meta-analysis of five cross-sectional studies showed significant reductions in C-reactive protein levels(Reference Wu, Chen and Tsai117). Similarly, another meta-analysis of randomised trials found that the MedDiet significantly reduced systemic inflammation markers, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β and C-reactive protein(Reference Koelman, Egea Rodrigues and Aleksandrova131).

Evidence on the components of the MedDiet supports its anti-inflammatory effects, with olive oil identified as a key element shown to reduce inflammatory markers. A meta-analysis reported that olive oil significantly lowered C-reactive protein and IL-6 levels, particularly in interventions lasting longer than 3 months(Reference Aparicio-Soto, Sanchez-Hidalgo, Rosillo, Castejon and Alarcon-de-la-Lastra132–Reference Fernandes, Fialho, Santos, Peixoto-Placido, Madeira and Sousa-Santos134). Specifically, the phenolic compounds found in olive oil are reported to play a significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role(Reference Cicerale, Lucas and Keast133,Reference Covas, Nyyssonen, Poulsen, Kaikkonen, Zunft and Kiesewetter135) . Apart from an increased intake of health-promoting food items, the MedDiet is low in red meat, processed/ultra-processed food, refined sugar and alcohol, which are all pro-inflammatory(Reference Hosseini, Berthon, Saedisomeolia, Starkey, Collison and Wark136–Reference Wang, Uffelman, Hill, Anderson, Reed and Olson138).

A strong association of inflammatory markers and cytokines with mental illnesses, specifically depression, has been well documented. Results from two meta-analyses showed a positive association between circulating inflammatory biomarkers and depression(Reference Dowlati, Herrmann, Swardfager, Liu, Sham and Reim139,Reference Howren, Lamkin and Suls140) . Pro-inflammatory cytokine production interferes with neurotransmitter metabolism and decreases the availability of some precursors, including tryptophan(Reference Miura, Ozaki, Sawada, Isobe, Ohta and Nagatsu141). Although cortisol reactivity to acute stress is key for survival, repeated activation increases pro-inflammatory cytokines and may trigger the onset of depression and anxiety(Reference Dickerson and Kemeny142,Reference Segerstrom and Miller143) . In addition, tryptophan also modulates other neurotransmitter synthesis such as dopamine and norepinephrine(Reference Sanger144). Lastly, tryptophan and its metabolites (such as melatonin) can result in reduction of the inflammation state by promoting an optimal mood state(Reference Achtyes, Keaton, Smart, Burmeister, Heilman and Krzyzanowski145,Reference Garcez, Jacobs and Guillemin146) .

Low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction can suppress brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression, thereby diminishing its neuroprotective effects and potentially contributing to neuronal dysfunction(Reference Guo, Kim, Lok, Lee, Besancon and Luo147). Meta-analyses have demonstrated lower BDNF levels in individuals with depression, which tend to increase with antidepressant treatment, underscoring the potential anti-inflammatory role of the MedDiet in supporting mental health(Reference Bocchio-Chiavetto, Bagnardi, Zanardini, Molteni, Nielsen and Placentino148,Reference Sen, Duman and Sanacora149) .

Gut microbiota

Recently, attention has been given to the effect of the MedDiet on the gut microbiota. Specific nutrients, particularly insoluble fibre and protein, have significant effects on gut microbiota structure, function and secretion(Reference Clemente, Ursell, Parfrey and Knight150). Metabolites secreted from the gut have a key role in modulating immune function and several metabolic and inflammatory pathways(Reference Clemente, Ursell, Parfrey and Knight150,Reference Richards, Yap, McLeod, Mackay and Marino151) .

Previous studies noted that diets rich in insoluble fibre promote gut health(Reference Holscher152). The MedDiet is rich in insoluble fibre, making it particularly beneficial for gut health(Reference Richards, Yap, McLeod, Mackay and Marino151,Reference Haro, Garcia-Carpintero, Rangel-Zuniga, Alcala-Diaz, Landa and Clemente153) . High adherence to the MedDiet has been associated with favourable changes in gut microbiota, specifically, increased levels of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes and elevated faecal short-chain fatty acid concentrations(Reference De Filippis, Pellegrini, Vannini, Jeffery, La Storia and Laghi118).

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), produced by gut microbes from undigested fibre, help regulate inflammation(Reference Hu, Lin, Zheng and Cheung154,Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou, Bamia and Trichopoulos155) . Among them, butyrate is particularly noted for its anti-inflammatory effects(Reference Hartstra, Bouter, Backhed and Nieuwdorp156–Reference Asarat, Vasiljevic, Apostolopoulos and Donkor160). Similarly, beneficial gut bacteria such as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bifidobacterium are associated with reduced systemic inflammation(Reference Cani, Neyrinck, Fava, Knauf, Burcelin and Tuohy161,Reference Ferreira-Halder, Faria and Andrade162) .

Probiotics and living microorganisms, typically yeasts and bacteria, are known to promote a healthy gut microbiome(Reference Alkalbani, Osaili, Al-Nabulsi, Olaimat, Liu and Shah163). In this regard, probiotic supplementation was reported to change gut microbial structure, and these changes in microbial structure have been found to be associated with reduced anxiety and depression-like symptoms(Reference Liu, Cao and Zhang164), further showing the central role of gut microbiome in mental health. However, most of these reports are based on animal studies.

Discussion

The MedDiet was shown to be associated with improved mental health outcomes, including depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, stress, mental wellbeing and quality of life, in adult populations. Possible mechanisms involved include the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of the MedDiet and its effect on gut microbiota.

The association between a MedDiet and depressive symptoms is stronger and more consistent in cohort studies, while cross-sectional studies show mixed results. This difference may be because of the inherent limitations of cross-sectional designs in capturing the temporal relationship between exposure (MedDiet) and outcome (depressive symptoms)(Reference Wang and Cheng165). Similarly, interventional studies comparing the MedDiet with usual care or other diets have shown improvements in depressive symptoms. Notably, the SMILES trial also reported the remission of symptoms among individuals with major depression(Reference Jacka, O’Neil, Opie, Itsiopoulos, Cotton and Mohebbi11).

The findings of this study align with a meta-analysis reporting that MedDiet interventions significantly reduce depressive symptoms in relatively young populations (aged 22–53 years) diagnosed with depression(Reference Bizzozero-Peroni, Martinez-Vizcaino, Fernandez-Rodriguez, Jimenez-Lopez, Nunez de Arenas-Arroyo and Saz-Lara166). Similarly, another systematic review and meta-analysis study reported that the MedDiet presents the most compelling evidence in reducing the risk of depression than other healthy dietary indices such as the healthy eating index (HEI), the alternative HEI (AHEI) and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(Reference Lassale, Batty, Baghdadli, Jacka, Sanchez-Villegas and Kivimaki167–Reference Sanchez-Villegas, Henriquez, Bes-Rastrollo and Doreste171). However, the above-mentioned studies lack comprehensiveness, primarily focusing on the role of the MedDiet in depressive symptoms.

The association between the MedDiet and depression across diverse settings and populations is generally consistent, though some studies report no association. Variability in measuring both the MedDiet and depression likely contributes to these inconsistencies, possibly owing to some of the existing MedDiet scores not fully meeting applicability criteria(Reference Zaragoza-Marti, Cabanero-Martinez, Hurtado-Sanchez, Laguna-Perez and Ferrer-Cascales172). The term ‘applicability’ usually refers to concepts regarding the demands of the administrator and respondent, alternative forms and interpretability(Reference Aaronson, Alonso, Burnam, Lohr, Patrick and Perrin173). On the basis of a recent systematic review on the evaluation of MedDiet adherence scores, very few scoring measures obtained the best evaluations in terms of applicability(Reference Zaragoza-Marti, Cabanero-Martinez, Hurtado-Sanchez, Laguna-Perez and Ferrer-Cascales172), whereas the score created by Sotos-Prieto et al. (Reference Sotos-Prieto, Moreno-Franco, Ordovas, Leon, Casasnovas and Penalvo174) has recent evidence supporting its reliability.

In addition, a difference in the measurement of depression partly plays a role, which may be attributable to the effects of comorbid health conditions that might reflect distinct phenomenological features of depression(Reference Yang and Jones175).

A relatively consistent association of MedDiet score with reduced anxiety is reported. The majority of studies are cross-sectional, whereas very few clinical trials and longitudinal follow-up studies are available. The MedDiet is also associated with improvements in quality of life, stress and wellbeing. While the findings suggest a positive role of the MedDiet, the limited number of studies underscores the need for more high-quality research in this area.

Implications

The MedDiet has been widely studied across diverse regions, suggesting its potential adaptability to various populations. However, successful adoption may be challenged by factors such as limited access to fresh, high-quality ingredients(Reference Yassibas and Bolukbasi176) and the difficulty of maintaining long-term adherence to specific dietary recommendations(Reference Leme, Hou, Fisberg, Fisberg and Haines177). Furthermore, the feasibility of adopting the MedDiet across diverse populations warrants further exploration, particularly in light of cultural, socio-economic and geographical factors. These findings also highlight the need to investigate how the MedDiet can be effectively integrated into comprehensive treatment and prevention strategies for mental health outcomes. The findings also underscore the growing significance of nutritional psychiatry, an emerging field that emphasises the role of diet in the prevention and management of mental disorders.

Another implication of the findings is the need for future research to more frequently utilise clinical diagnoses of mental health outcomes. The majority of existing studies mainly utilised screening tools to assess mental health outcomes. Although widely used screening tools for mood disorders (such as the Beck Depression Inventory Scale version II (BDI-II) and BAI) are well-validated, their self-reported nature may affect the reliability of the data(Reference Hobbs, Lewis, Dowrick, Kounali, Peters and Lewis178,Reference Cuijpers, Li, Hofmann and Andersson179) . Thus, more studies with clinical diagnosis of mental health outcomes as a primary outcome might provide stronger evidence(Reference Hobbs, Lewis, Dowrick, Kounali, Peters and Lewis178). In addition, high-quality clinical trials with longer follow-ups are needed across diverse populations to clearly understand the long-term benefits and to robustly establish causal inferences to facilitate evidence-based policies and strategies.

Conclusions

The MedDiet has shown promising results in improving mental health by reducing depressive symptoms and enhancing psychological wellbeing in adult populations. Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms and optimal integration of the MedDiet into comprehensive treatment plans. It is important to note that the efficacy of a MedDiet in combatting mental health issues may be subject to integration into wider mental health treatment strategies.

This review highlights a growing body of evidence suggesting that adherence to the MedDiet is associated with favourable mental health outcomes, including reductions in depressive and anxiety symptoms and perceived stress, as well as improvements in quality of life and overall mental wellbeing. Notably, while the majority of studies, particularly longitudinal and interventional designs, support the protective role of the MedDiet, inconsistencies, particularly among cross-sectional studies, point out the influence of context, population characteristics and methodological heterogeneity, such as varied dietary and psychological assessment tools. In addition, the emerging understanding of potential pathways includes antioxidant potential, anti-inflammatory effects and improved gut health. However, the existing evidence still lack robust causal inference, and many studies remain observational or with short-term interventions, with limited exploration of dose–response relationships, differential effects by subgroups (e.g. sex, age and comorbidity status) or long-term sustainability of diet-related changes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422425100243

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

R.H.K. is supported by graduate scholarships provided by Monash University.

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interest.

Authorship

The authors’ contributions were as follows: R.K.: designed research, screened studies, undertook study, extracted and summarised the data and wrote the paper. J.F.: screened data and contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. L.K., K.L., M.L., R.M., S.M., S.B., C.N.O., M.F.C., H.S., R.C., M.T., S.M., L.S., A.T. and C.I: contributed to editing and revising the manuscript. B.d.C.: final editing and revision of the manuscript. All authors: provided intellectual input in line with ICMJE criteria for authorship and read and approved the final manuscript.