Introduction

This article contributes to a central debate within feminist economics: how does paid and unpaid childcare shape gender relations and the social fabric of societies? Guided by a generous tradition of work in feminist economics that discusses the centrality of gender relations and inequalities via childcare, our research sought to understand what the gender consequences of childcare distribution are. Inspired by the work of Razavi (Reference Razavi2007), we conducted two years of research seeking to identify and understand the distribution of childcare in Mexico. We aimed to understand the intricacies of concealed forms of childcare, especially in the domestic realm, and their connection to public provision.

The need to address different sources of childcare, especially informal and opaque arrangements, became evident. Thus, we applied Razavi’s diamond model to identify the social dimensions in which childcare is performed, and the actors, institutions, and dynamics that shape this activity. The diamond model recognises four dimensions: family/household, the State, the Market, and not-for-profit (NFP).

Our study follows each dimension of the diamond, conducting a sectorial analysis examining institutions, individuals, and arrangements that provide paid and unpaid childcare work in Mexico. To do so, we explore national statistics, including representative surveys, from the Mexican National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), complemented by the examination of programmes and policies in published studies.

The article is structured as follows. First, we provide a literature review on the development of models to measure welfare distribution, focusing on care provision. Second, we summarise important aspects of the Mexican context to situate our analysis. This is structured according to each dimension of the diamond, delving into family/household, the State as public childcare provider, the market provision, and the NFP sector. We summarise our findings in a discussion, followed by final remarks highlighting the advantages and shortcomings of using the model.

We answered the question of what the gender consequences of care arrangements in Mexico are by showing how the distribution of childcare – paid and unpaid – contributes to (re)producing and strengthening traditional gender roles across a myriad of spaces, dynamics, and arrangements. By using the care diamond, we highlight the potential of certain spaces, such as the NFP sector, in approaching and thinking about childcare outside familial models that define it as a mother’s and women’s responsibility within the domestic sphere.

By implementing this model, we provide a concrete empirical case, offering a well-rounded depiction of childcare in Mexico. Thus, we contribute to current studies on gender inequalities connected to welfare policies – and the lack thereof. On a theoretical level, we advance the explanatory potential of the diamond conceptual framework for countries with a weakened or limited welfare system and a significant presence of informal arrangements. We highlight empirical and conceptual elements for Latin American development pathways sensitive to context-specificities, more closely aligned with countries and societies within the Global South.

The diamond model: a literature review

Gaining recognition of unpaid care as work, and women’s role in providing it, is a long-standing endeavour within feminist economics (England and Folbre Reference England and Folbre1999). The concealment of care in the domestic realm has contributed to the difficulty in assessing its enormous socio-economic contribution (Folbre Reference Folbre2006, 185; Araujo Guimarães Reference Araujo Guimarães, Araujo Guimarães and Hirata2021, 127). Care is a unique type of work, an activity that requires affectionate, relational, and emotional components with a centrality in the provider. Folbre and Weisskopf (Reference Folbre, Weisskopf, Ben-Ner and Putterman1998, 127) criticise a neoclassical perspective on care restricted to a provision of services, without considering motives, attitudes, and shared expectations involved in performing it. Folbre (Reference Folbre2006, 185) argues for the need to go beyond definitions of work based on the site of production (domestic vs market sphere), which result in conventional statistics hiding the costs of unpaid care work.

Models contribute with a comprehensive perspective on how paid and unpaid care happens and is distributed in a given society and time, conveying an architecture and connections between providers. Initial formulations considered three dimensions – State, family, and market – as welfare triangles. Empirical applications made evident the need to incorporate, define, and measure unpaid sources of care beyond the family (Jenson and Saint-Martin Reference Jenson and Saint-Martin2003). The transition from the welfare triangle to the diamond emerged in studies such as Payments for Care by Evers et al in 1994 (Wijkström Reference Wijkström1996), which described the diamond comprising State, market, voluntary sector, and family. This pioneering work examined several case studies, providing an analysis from a macro to a microlevel of individuals and across several cultural, political, and religious settings. It solidified the role, responsibilities, and extent of the ‘family’ and the ‘State’. Yet, it lacked conceptual and empirical characterisation of the market and, especially, unpaid collective forms of care; the latter was portrayed as uncommon, which demonstrates a lack of understanding of ‘basic structure(s) and modus vivendi of society at large’ (Wijkström Reference Wijkström1996, 87).

Folbre (Reference Folbre2006) calls for ‘reimagining care’ from a perspective that recognises other actors, institutions, dynamics, and arrangements involved in the provision of care. By understanding that care may happen in fragmented, simultaneous, and diverse ways, we open the door to consider the weight of an array of actors and institutions involved in care provision, including communities and collective actions (Glenn Reference Glenn, Araujo Guimarães and Hirata2021).

Altogether, voluntary and informal arrangements for care appear to fulfil significant social functions. These arrangements compensate for the decline of services previously offered by highly institutionalised public systems and act as an answer to ‘the crisis of the welfare state and the need of “a new social pact”’ (Wijkström Reference Wijkström1996, 90). However, institutional shortcomings resulting from the retrenchment of welfare regimes are not a new phenomenon if we shift the focus from the Global North to the Global South, and especially to Latin American and Caribbean countries. Among the latter, most never reached the level of institutionalisation of care that many authors refer to as the classical Welfare State.

Razavi’s model considers four main dimensions: State, market, family, and NFP. The author identifies specific forms of care in each dimension and, by doing so, signifies the distribution of welfare and care work as ways in which social fabric and gender inequalities are reproduced. Her argument is that identifying how care happens in each of these dimensions provides a solid understanding of how the social fabric and gender inequality are reproduced (Razavi Reference Razavi2007, 4). Salvador (Reference Salvador2007) uses Razavi’s conceptual framework in her comparative study of the care economy in various Latin American countries. In Figure 1, we bring together both formulations of the diamond and show how Salvador’s work provided details of social actors and institutions in the Latin American case.

Figure 1. Initial formulation of the care diamond by Razavi and advanced formulation by Salvador (Reference Salvador2007).

Source: elaborated by authors based on Razavi Reference Razavi2007, fig 1 and Salvador Reference Salvador2007, 9.

Salvador (Reference Salvador2007) applies Razavi’s model in her comparative study of the care economy in various Latin American countries. In doing so, she enriches the model with detailed actors involved in each dimension. The author identifies the State as a care provider in the centre, seeing how other dimensions articulate around it. How the State performs welfare outlines a regime in each society and defines the weight of care work in the other three dimensions. Salvador organises care work into familistic and non-familistic models. In Latin America, the former model is dominant, involving care work performed predominantly by women in the family/kin, making it a feminised, unpaid responsibility. Non-familistic regimes, less present, transfer care to public institutions and/or the market, complemented by families and informal networks.

The empirical application of the model: challenges and advancements

Accounting for NFP care provision is necessary due to its presence and importance in the Latin American context. However, it presents several challenges, including data, how care is provided, its structure, dynamics, and actors. From a global perspective, Razavi (Reference Razavi2007, 21) defines the NFP as a ‘heterogeneous cluster of care providers that is variously referred to as the “community”, “voluntary”’. In the Latin American context, Glenn (Reference Glenn, Araujo Guimarães and Hirata2021) understands it as constituted by community, religious and charitable organisations, networks of parents, and neighbourhood-level-based arrangements.

Fraga (Reference Fraga2022) offers a deeper examination of the region. She posits territory – as material and symbolic space – as a key driver of community care. She argues it is the common experience of unmet basic needs by women and families in a shared space that leads to collective action. Fournier’s study in Argentina (Reference Fraga2022) shows that low-income women are the main agents involved in creating and sustaining NFP care initiatives. Collective and community actions are strongly framed by gender norms, with a predominance of women’s agency. These initiatives can assuage the volunteers’ own care work, as their children are included in these spaces, receiving food, attention, and some monetary compensation for their collaboration (Fraga Reference Fraga2022).

These most recent studies show that, altogether, experiences of NFP childcare in Latin America and the Caribbean are ‘initiatives led and sustained by women that allow for a certain decentralisation of households’ (Fraga Reference Fraga2022, 14). Through exchange and non-monetary support, communities living in poverty, exclusion, and vulnerability deploy a plethora of actions, strategies, and practices to address unmet basic needs. In doing so, they contribute to the defamilisation of care as it is performed by groups and organised by commitment, solidarity, and shared responsibility.

We contribute to the current research and literature by applying the diamond model in Mexico, expanding and deepening the context-specificities of the dimensions. Following Salvador, we provide the concrete articulation of the actors involved in care provision in each dimension of the diamond, granting bases for future comparative studies within the region and other countries. We identify the actors and forms of care which constitute each dimension, as well as their interactions. Specifically, we show that the family/household sphere is being permeated and shaped by market relations. This is occurring through the increase of private care arrangements within the house, many of which are informal, amid a context of reduced public childcare provision. We also challenge the institutional definition of the NFP sector by i) recognising informal aspects of it and ii) stressing the protagonism of vulnerable women in making them come to reality, in contrast to perspectives that see charity, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), or international help as the main vector of organisation. Thus, we bring forward the importance of gender in informal community, kinship, and neighbourhood networks working outside institutionalised venues.

The Mexican context

Before delving into the analysis, it is important to offer a succinct depiction of inequalities derived from gender disparities and policies/institutionalised dimensions. In Mexico, women experience the burden of domestic and care work in the private realm (Valenzuela et al 2022; ECLAC 2022). This hinders their economic inclusion and financial autonomy, maintains gender gaps and power disparities (ECLAC 2022; Garnica-Monroy and Hernández-Reyes Reference Garnica-Monroy and Hernández-Reyes2022, 558). As of 2022, the difference between the labour force participation of men and women in Mexico stands at 32.9 p.p. in detriment of the latter.

It is not uncommon that women’s paid occupation acts as a ‘buffer zone’ for the economy, being ‘activated’ and ‘de-activated’ due to changes in the economic scenario (Duque-Garcia Reference Duque-Garcia2021, 21). Women’s consistently higher informality rate – a strong indicator of accommodating double burden – makes them particularly vulnerable. Wages and the coverage of social security are lower in the informal sector, and informal workers are more exposed to income losses. Precariousness and exposure have a significant impact on families and children’s well-being, especially when not counterbalanced by institutions and policies.

In the 1980s, Mexico experienced an unexpected demand for public childcare due to an increase in women’s participation in the labour market (Juárez Hernandez Reference Juárez Hernández2010). The Secretary for Public Education had difficulties coping with the expenses of expanding childcare. Alternative strategies were adopted – training young educators with community leaders and seeking modernisation of basic education and preschools. Since the late 1980s, Centres for Child Assistance (CAIs) have been created to provide care for children of working mothers from 45 days old up to 6 years old. CAIs are regulated by a federal law, regardless of whether they are public, private, or with mixed funding and may offer full-day care, support for education, and diverse activities.

While the State’s responsibility in providing childcare is defined by legislation, some authors characterise it as highly unstructured, with limited institutional design and articulation, unable to attend to low-income families and women, and hampered by regional inequalities (Juárez Hernandez Reference Juárez Hernández2010; Estrada Reference López Estrada2020). Geographical distances are key to analyse the availability and use of CAIs. In low-income, rural, and indigenous areas, the scarcity of public CAIs means no childcare is available as families lack resources to commute. In 2022, more than 90% of parents and legal guardians from indigenous, low-income, and rural areas who take their children to public CAIs do so on foot (CONEVAL and UNICEF 2022).

Limited public support for childcare is part of a wider reduction of resource allocation in Mexico. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) México (2023), public investment in childhood and adolescence in the last ten years has corresponded to 3% of the GDP, below the regional average of 5%. While public spending in the country has increased in the last decade, social protection targeting childhood and adolescence has lost fiscal space from 2.6% of the budget in 2012 to 0.7% in 2023 (UNICEF México 2023). The retrenchment of the Welfare State is to take the current struggle of many families in receiving and providing care into a crisis (Matos de Oliveira and Alloatti Reference Oliveira and Alloatti2022; Orozco Reference Orozco2006).

Aligned with the temporal scope of our study on childcare provision, we highlight the case of the dissolution of the Programme Childcare Centres (PEI) in 2018. The programme was created in 2007, under the Secretary for Social Development, to care for children up to 4 years of age whose mothers were working, studying, or looking for a job or who were the children of single fathers who were working and studying. The PEI covered 10 states and had a mixed care approach, transferring money to families and providing financial support to public and private CAIs.

The programme faced difficulties in resource allocation in vulnerable and rural areas, reproducing geographical inequalities and exclusion. It also had a gender bias due to the key concept of ‘working mothers’. Single fathers needed to effectively prove they did not have a female member in the household to become beneficiaries, reproducing the existing sexual division of childcare (López Estrada Reference López Estrada2020, 4–8; Mateo-Berganza Diaz and Rodríguez-Chamussy Reference Mateo-Berganza Diaz and Rodríguez-Chamussy2017)).

Nevertheless, the PEI showed several positive aspects. In 2007, 5,504 CAIs existed, and 125,359 children were enrolled. By 2016, the programme had 9,195 CAIs and 315,000 children enrolled. Evaluations underlined a positive perception of mothers, strong indicators of children’s well-being, qualified personnel, improved coverage in rural and vulnerable areas and, most notably, promoting low-income mothers returning to the labour market (López Estrada Reference López Estrada2020, 13).

In 2018, the PEI was replaced by the Programme for Wellbeing of Children and Working Mothers. This programme puts the well-being of children at the centre, leaving the support for working mothers in a second stage. A key change was the reduction of the budget to private CAIs that had vacancies for children, and funds were shifted to direct cash transfers to legal guardians (Garcia 2023). This change in resource allocation compelled families to seek other sources of childcare, such as private CAIs or informal arrangements with nannies. The dissolution of the PEI had several consequences, many of which could only be fully comprehended in the long run. Some authors understand it has led to a process of re-privatisation of care, as a movement that brings childcare from institutionalised spaces back to the private sphere (López Estrada Reference López Estrada2020; Carrión et al. Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022). It is with this background our analysis investigates the current distribution of childcare in Mexico.

Methods

Our study uses two main sources of data. Primarily, we conduct a descriptive analysis of secondary statistics, produced by the INEGI, including national and satellite accounts. We also used a series of national surveys based on representative samples. We extracted the survey data and controlled it with the quarterly and annual publication of key findings of each survey. We analysed the following surveys conducted by the INEGI: Survey for Care Services (INEGI ENASIC 2023a); Survey for Occupation and Employment (INEGI ENOE 2023b); Satellite Account for Non-for-Profit institutions (INEGI CSISFLM 2023c); Survey for Access to and Retention in Education (INEGI ENAPE 2022); Survey for Time-use in Domestic and Care Work (INEGI ENUT 2019).

We sought to maintain a scope of time from 2018 to 2022, but we extended it when data series were available, and we considered it advantageous to see changes throughout time. Two important caveats apply. In some cases, data from 2020 is not accurate or was not gathered due to social distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, while we tried to distinguish the multiplicity of actors, institutions, resources, and spaces involved in childcare provision, this was not possible in all four dimensions. In some surveys, available data uses different units of analysis (i.e., children, households) and do not possess information on income or social class background. When possible, we explicitly considered these limitations.

Secondly, we examine published studies based on empirical research and in-depth policy analysis of the Latin American region and Mexico, with special focus on care, gender inequalities, vulnerability, and policies. We primarily used peer-reviewed scientific publications, independent programme implementation and evaluations, and policy advising notes by United Nations (UN) agencies.

To apply the diamond model in Mexico, we operationalised its dimensions as follows:

-

The family/household dimension includes unpaid work and indicators of women’s labour market participation. We consider childcare performed within the boundaries of the household, but do not include privately engaged care services, which are examined in the market dimension.

-

The public sector dimension examines data on public spending, considering funding, infrastructure, and characteristics of State-owned CAIs. We examine the public dimension of childcare provision, primarily focusing on the effective supply of CAIs and their characteristics. However, this is not the full scope of the State as an actor, which requires us to consider its role in regulating and supervising the private sector, as well as possible support to the NFP sector. We refer to these aspects within the respective sections.

-

The market dimension considers private services (in and outside households), establishments, costs, characteristics of the services provided and the relationship between public funding and private services through social security. Nowadays, two types of public childcare exist in Mexico:

-

i) the nation-wide public system with CAIs attending families without social security, seeking to support especially those in rural and/or vulnerable areas;

-

ii) public and private CAIs under social security, which cover only those with formal working arrangements. The latter are under the Institute of Security and Social Services of State Workers (ISSTE) and the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), which we detail in the subsection ‘Market’.

-

The NFP dimension focuses on the distribution of paid and volunteer workers, characteristics of social services, and includes some case studies that allow us to examine the complexity of this type of provision.

Analysis of childcare distribution in Mexico

The family/household dimension: the impacts of the domestic provision of care

In Mexico, although women have a lower participation rate in the labour market, on average, they work more hours than men if paid and unpaid time are added together, as women spend a higher weekly average of hours in unpaid domestic and care work than in paid work. Among men, the opposite happens. Altogether, this conveys strong limitations to women’s economic autonomy, although the idea of women as ‘inactive’ does not hold. Disaggregating by types of work - in 2019, women spent 39.7 hours per week in unpaid domestic work and almost the same amount (37.9 hours) in unpaid care work (INEGI ENUT 2019). Additionally, they spent around 10 hours in unpaid work supporting other households or doing voluntary work.

The presence of small children in the household impacts women’s availability and insertion in the labour market. Between 2000 and 2022, women with small children consistently spent less time in paid work (around 54 minutes less) than those without, again impacting their economic autonomy. Between 2016 and 2020, the difference of 1.3 hours of paid work for women without minors at home was stable, reaching the highest point of the series (since 2000) of 1.5 hours of paid working hours in favour of those without minors (ECLAC CEPALSTAT 2024). Caring for children includes a plethora of practices, beyond feeding, bathing, and washing. The National Survey for Education (INEGI ENAPE 2022) shows that mothers are the main adults supporting school work. Mothers supported 91% of preschoolers, 82.4% of those in primary school, and 51.5% of those in secondary school.

The demand for care in the household shows that, according to the 2022 National Survey for Care System, 31.7 million people of 15 years or older provided care for someone, and 28.3 million provided care for a member of their own household (INEGI ENASIC 2023a). Within this group, 75.1 % are women and 24.9 % men. Women were also overrepresented among the main caregivers (86.9% of the total), meaning they are the main source of care even when other people or institutions provide it, compared to men (13.1 %). Women providing care reported this activity made them ‘feel tired’ (39.1%), had ‘diminished their sleep time’ (31.7%), made them ‘feel irritability’ (22.7%), ‘feel depressed’ (16.3%), and ‘saw their physical health affected’ (12.7%) (INEGI ENASIC 2023a).

In 2022, 91.5% of children between 0 and 2 years old did not attend early education. The choice about sending or not sending children to be cared for outside the household is influenced by different factors. The main reason, reported by 85.5% of families, is that children are ‘too young’ or ‘it is not necessary’ for them to attend CAIs. Yet, a small group, 9.1%, reported that CAIs were not available or too far away or distant (INEGI ENASIC 2023a). In 2022, 57.3 % (46 million) of the adult population (15 to 60 years old) considered it positive that children spent time at childcare centres, including public CAIs. Valued characteristics of public establishments were qualified personnel (77.3 %) and safe and adequate conditions and infrastructure (52%). Yet, a significant portion of the sample, 42.7%, rejected the idea of young children spending time in CAIs. 53.2% mentioned that childcare is the responsibility of the mother, father or the family, and 21.4 % reported that children were mistreated in CAIs (INEGI ENASIC 2023a).

Estrada (Reference López Estrada2020, 11) argues that in Mexico, mothers have a strong preference for carrying out childcare personally, or opting for a family member to do it, even when payment is involved. We echo the author in stressing the paucity of information regarding how this choice is made, including the impact on income, time-use, rural/urban areas, and the diversity of women and families in the country. In a qualitative study conducted in Mexico City, Muller and Jaen (Reference Muller and Jaen2020) identify two main aspects that inform decisions around outsourcing childcare. Two main factors are: i) women’s aspirations, the role of work in their lives, and support received and ii) the availability of care, convenience, quality, children’s wellbeing, risks and safety.

Muller and Jaen underline that those in vulnerable situations and with low educational attainment do not perceive many options, including public childcare. These women reported support from other women within the family and networks. Equally important for this demographic is that not directly caring for their children questions their identity as mothers and women (Muller and Jaen Reference Muller and Jaen2020, 19). Among middle-class women with a higher educational attainment, motherhood involves working inside and outside the house and discrimination in the workplace. However, unlike women from lower-income groups, they count on sources of childcare such as their partner and/or a paid caregiver.

The public dimension: characteristics and uses of childcare supply

The National System for Integral Family Development (DIF) supervises CAIs in the country. For those without social security, the DIF provides vacancies in public CAIs to care for children between 45 days and 6 years of age. For the years 2019–2020, the DIF reported that 25.8% of formally registered CAIs in the country were public (2,549), 45.0% (6,301) were private, and 7.5% (1,048) were mixed-funded. The study also showed a predominance of private CAI in richer states.

An expansion in social security law (in article 201) that ensures childcare for mothers and (recently included) fathers produced an expansion of 14.19% of the target population of the IMSS between 2015 and 2022, according to the yearly evaluation by the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) (2023a). It is key to understand how this increased demand was addressed. Firstly, according to the CONEVAL, enrolment is not prioritised based on parents’ gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic condition. As a result, historically disadvantaged groups have not been considered. Moreover, in 2022, we can see that more men have benefited from the program (91,025) compared to women (83,495), possibly due to gender disparities in accessing formal employment.

We delve into the IMSS specificities in the following section due to its intertwining with the market sector; still, we clarify here the kind of provision available. The IMSS’s provision may be ‘direct’ (vacancies in CAIs that belong to the IMSS) and ‘indirect’ (which refers to private CAIs with a contract with the IMSS to provide vacancies for children or a payback arrangement for childcare fees). For 2024, the indirect provision of childcare represents almost ten times the direct provision. This means that resource allocation happens mostly through arrangements with third parties, and there is no data disaggregating the type of provision under the indirect classification. Moreover, it increases the vulnerability of the public provision as it can be reduced due to the suspension or non-renewal of contracts by the private party. That is, a CAI meeting a strategic geographical demand may close its door unexpectedly.

While options and choices are significantly different for women in low-income and middle-class positions, distrust in the public childcare system is broad. López Estrada (Reference López Estrada2020) and Salvador (Reference Salvador2007) argue that women report insecurity and even fear of services in public centres. Lack of information seems to be crucial. The main channel of information between the centres and parents is personal contacts, which individualises the experiences and creates feelings of unequal treatment. Distrust increases in the cases of children with disabilities involving fears of mistreatment. (Carrión et al. Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022, 22). Among low-income households, lack of trust in public CAIs and resistance to leaving children with ‘other people’ are salient, with this seen as an uncommon behaviour (CONEVAL 2023a, 99).

Yet, it is noteworthy that those who reported being willing to send their children to the public childcare centres were mothers who wanted to work, residing in urban areas, and lacked support networks (CONEVAL 2023a, 96). Carrión et al. (Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022) mention several operational issues in accessing public childcare that impact those in vulnerable contexts – scarce vacancies, eligibility, and limited time schedules. Family members (grandmothers, older siblings) cannot enrol children in CAIs, a significant impediment for women who work outside or are relatively distant from the household. Thus, mothers express that the system creates more issues than solutions. Women who experience the heavier double burden are the least frequent profile among users of the public system, when they seek out the system, they convey accumulated exhaustion due to double burden (Carrión et al. Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022, 22, 34–35).

Consequently, the lack of consistency and availability of public childcare expands gaps between low- and high-income families through a disparity in personal and family resources (Muller and Jean Reference Muller and Jaen2020). Women and families with possibilities to access private care can solve and manage the situation, while those lacking resources face strong constraints and need new family arrangements to avoid the public system. The public childcare system seems considerably limited in addressing the needs of women providing care and its recipients in their diversity, such as ethnicity, social class, disability status, gender, and family background.

The market dimension: who provides care and who can afford it?

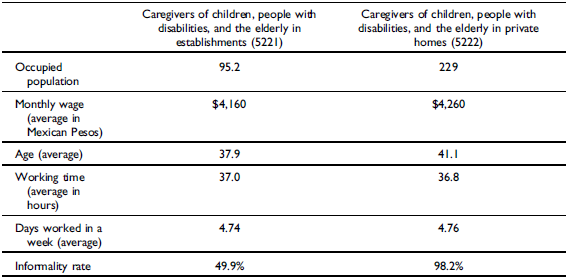

For the market dimension, we detail characteristics of private childcare provision, including costs, services, and workers. We then summarise recent data regarding private services intertwined with the provision under social security (IMSS) for formal workers. As a general depiction, we refer to the National Survey for Occupation and Employment as it offers detailed information on caregivers of children, people with disabilities, and the elderly in establishmentsFootnote 1 and in private homesFootnote 2 (INEGI ENOE 2023b). In Table 1, we show characteristics of paid private childcare in both spaces. We underline a considerable difference in numbers in favour of caregivers working at households, almost twice those in establishments and, equally important, a significantly higher informality rate.

Table 1. Caregivers of children, people with disabilities, and the elderly in establishments and private homes (Mexico, fourth trimester, 2022)

Source: INEGI. Based on National Occupation and Employment Survey – ENOE.

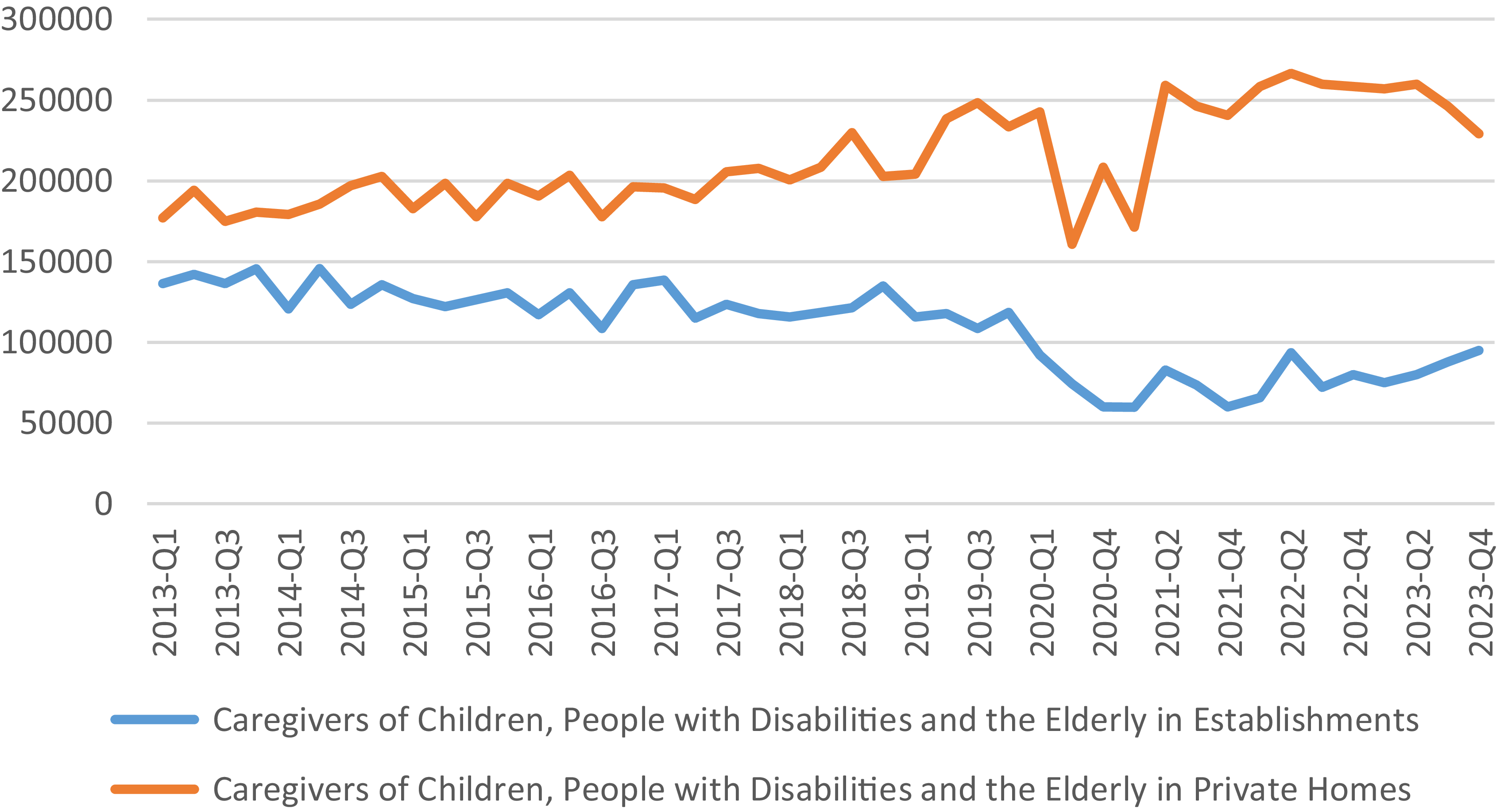

A comparison of trends between the number of workers in these two groups is shown in Graph 2. There is a visible decrease in the workforce in establishments, simultaneous to an increase of those working in private homes, with the exception of the peak of the pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of caregivers of Children, People with Disabilities and the Elderly in establishments and private homes (Mexico, 2013–2023, trimesters).

Source: INEGI.

Data on private CAIs, prices and fees for childcare services in Mexico are considerably outdated. The CONEVAL (2022) works with information from 2017, which we use to contextualise the private sector. In that year, the minimum wage was around 2,500 to 2,640 Mexican pesos per month. For the same year, 44% of families with children in private CAIs paid up to the equivalent of 1 minimum wage for this service. When the monthly fee moves up to between 1 and 2 minimum wages, there is a significant decrease in the number of children attending CAIs. It drops to 3.95% of the families for this value range, and 0.6% for CAIs charging an equivalent of 2 minimum wages or more.

The IMSS provides childcare as ‘direct provision’ (vacancies in CAIs that belong to the IMSS) and as ‘indirect provision’ (which refers to private CAIs with a contract with the IMSS to provide vacancies for children or a payback arrangement for childcare fees). The IMSS relies heavily on the indirect provision, which has reduced since 2009, from 1,568 CAIs to 1,143 in 2024. The direct provision by the State for 2024 is 126 CAIs, 15,142 beneficiaries, 16,130 enrolled children compared to the indirect provision of 1,143 CAIs, 16,577 beneficiaries and 175,417 enrolled children (IMSS 2018). The decrease in the number of CAIs, vacancies, and beneficiaries and the increase in unmet demand convey a clear reduction of the public provision of childcare. However, we stress an extra layer of complexity due to a previously utilised strategy to increase the number of vacancies among the existing CAIs.Footnote 3 This can lead to overcrowding and does not by itself address regional absences and disparities – regional differences, socioeconomic vulnerable areas of the country, vacancies for babies and children of certain age – a key vector of inequality in Mexico.

Considering the above-mentioned increase in the IMSS target population of around 14% between 2015 and 2022 (CONEVAL 2023b), we stress three main points around the State regulation of private services. First, the heavy reliance on ‘indirect provision’ without conditions for geographical location and enrolment prioritising ethnicity or socioeconomic condition. Second, the vulnerability of this provision is that private parties can suspend contracts unexpectedly. Third, the expansion of vacancies in already existing CAIs leads to overcrowding. Altogether, the reduced State regulation indicates the possible reproduction of inequalities and vulnerabilities.

NFP initiatives: gender, community, and provision of childcare

As discussed in the literature review, data on NFP initiatives in Mexico, as in many countries, is hard to gather as many community-based and collective actions are temporary, non-institutionalised and informal. Also, they frequently occur among hard-to-reach populations and involve an array of actors, communities, networks, and neighbours’ associations. To provide a proper depiction of this dimension, we examine national statistics and delve into some experiences to deepen our understanding.

The NFP sector in Mexico

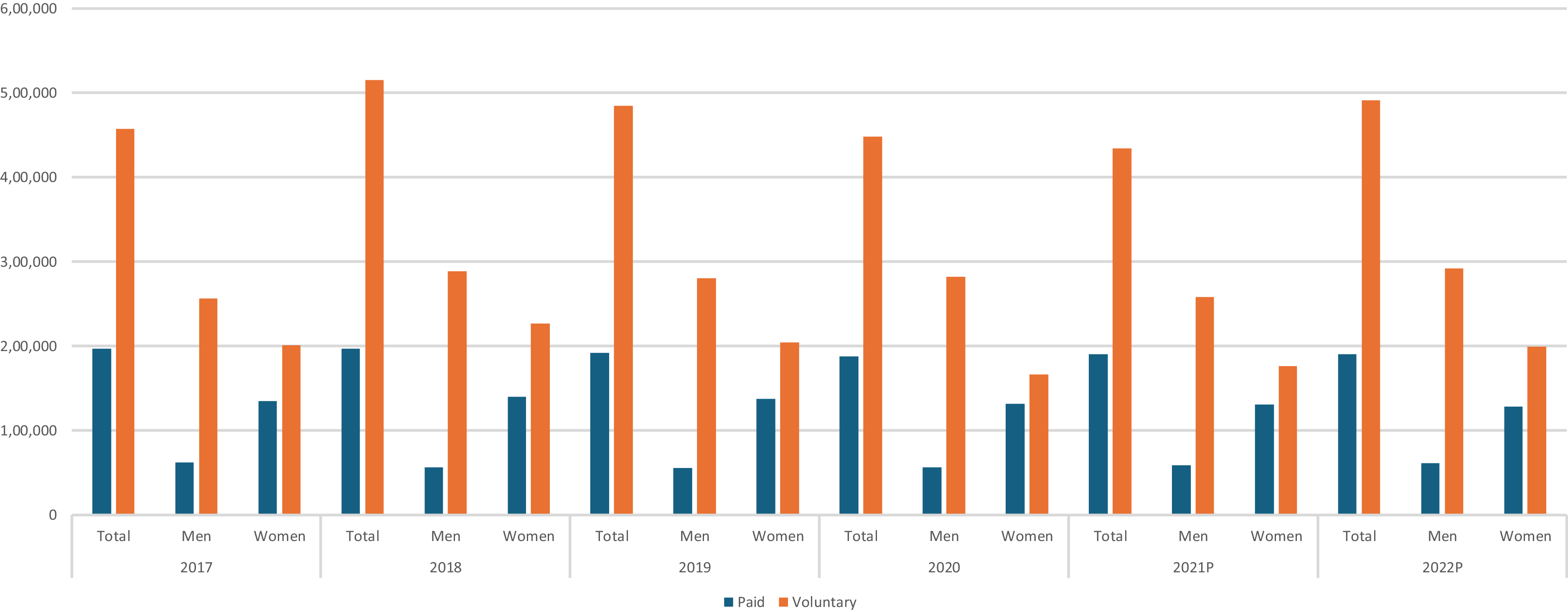

According to the satellite account for NFP institutions in México (CSISFLMFootnote 4 ) for 2022, the GDP of the sector represented 2.9% of national GDP (INEGI 2023c). We focus on associations classified by criteria that consider the service and its social objective as social services. This includes centres and actions providing daycare, supporting child development, and orphanages for babies. As a caveat, we state that in the INEGI data we analyse, NFP social assistance services may include some form of basic healthcare attention. In Graph 3, we analyse the distribution of paid and unpaid positions in NFP social assistance and health services by sex between 2019 and 2022 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Number of workers in health and social assistance at the NFP sector according to sex, paid, and voluntary work – Mexico (2017–2022).

Source: INEGI. National Account system. Satellite account Not-for-profit institutions.

We underline two points aligned with existing literature. First, voluntary work surpasses paid work by almost twice the number of total positions. This could produce a vulnerability in the provision of services, as volunteers may have a less stable participation and/or fluctuation in the hours dedicated to them. Second, there is an overrepresentation of women in paid positions. This aligns with studies that show it is frequent for women to have a higher participation in paid positions in NFP childcare arrangements in México (Fraga 2022).

While women may have work in paid positions may be positive, it does not exclude inequalities and precariousness. Available data does not indicate formal employment, remuneration, or social security benefits. Moreover, the extreme need to access these services via collaboration in these spaces or associations may hamper women’s autonomy in pursuing more beneficial jobs and financial independence. Additionally, participating in NFP associations or actions, even when paid, can be seen as an extension of domestic and care work, underestimating women’s workload.

We stress that it is difficult to single out childcare for analysis within NFP spaces. Studies in the region indicate that NFP initiatives address several needs simultaneously, such as care for children and the elderly, meals in communal kitchens, protection for women from gender-based violence, access to hygiene products, and health services (Fraga Reference Fraga2022; Fournier Reference Fournier2022; Carrión et al. Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022). Women participating in collective kitchens may benefit by feeding their own children, which alleviates the pressure on budgets, cooking time, and decision-making.

Experiences on geographical and social context as a vector for NFP actions

In Latin America, according to Fraga (Reference Fraga2022) and Fournier (Reference Fournier2022), women and families experiencing poverty, exclusion, and unmet basic needs in a shared space are the main actors in developing and sustaining NFP actions. The latter must be understood as anchored on a territorial scale: neighbourhoods, communities, rural areas, indigenous communities, and areas of extreme poverty. Low-income families and working mothers experience spatial segregation in a plethora of ways, including long commutes to their jobs, limited mobility, and restricted or absent public services (Garnica-Monroy and Hernández-Reyes Reference Garnica-Monroy and Hernández-Reyes2022).

A geographical analysis connecting vulnerability, poverty, and NFP initiatives is outside the scope of this study. Nevertheless, we examine selected noteworthy experiences in México. Juárez Hernández considers the efforts to address a higher demand for childcare in the 1980s (Reference Juárez Hernández2010, 1–2) by training community leaders among indigenous groups and vulnerable communities. According to the author, this qualification – which provided guidelines for child development in and outside the household – contributed to and strengthened social movements and actions since 1990, supporting the creation of NGOs that offer childcare in community centres employing mothers.

Fraga (Reference Fraga2022) explores community care amid increased gender violence in México in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. She examines the Sorority Network (Redes de sororidad), an indigenous community in the state of Chiapas, which created safe spaces for women escaping gender violence. Simultaneously, the community shared knowledge on growing poultry and crops using natural pesticides. This endeavour provided support for urgent needs, such as food for families, and knowledge to sustain these practices over time (Fraga Reference Fraga2022, 22–23).

NGOs have supported migrant children and families at several points in México, providing shelter, meals, and school support to children of migrant families (Estrada Reference López Estrada2020, 16). Montes and Paris Pombo (Reference Montes and Paris Pombo2019) and Valenzuela et al. (Reference Valenzuela, Scuro and Vaca Trigo2020, 55) examine care chains and care networks. The latter emerges as a horizontal and distributed involvement of individuals in caring for children, aligning with studies that highlight the importance of networks involving friends and non-family individuals in socioeconomically vulnerable families and communities (Carrión et al Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022, 34; Orozco Reference Orozco2006).

Findings and discussion

Applying the diamond model allowed us to capture the provision and distribution of childcare happening in Mexico along each dimension (family/household, market, public provision, NFP). In Figure 4, we offer a synthesis of our findings using as a base Razavi’s (Reference Razavi2007) original formulation and Salvador’s (Reference Salvador2007) detail of actors and institutions to depict the Mexican case.Footnote 5 With the original proportional diamond as a template, we fit a non-proportional diamond shaped by our assessment of childcare provision in Mexico. The disproportionality of our – inside – diamond expresses the reduction of some dimensions, as well as the interactions among dimensions. To better express these interactions, we use two types of arrows indicating if childcare is being transferred from one dimension to another due to restriction or articulation/collaboration between dimensions.

Figure 4. The diamond care model applied to Mexico.

Source: Own elaboration.

We stress three main findings to discuss. First, the State is the most significantly reduced, both as a dimension in childcare provision and as an actor considering its effective regulation of other dimensions. It presents diminished funding in public CAIs, policy changes involving cash transfer to families, and high reliance on third parties for childcare provision (indirect provision). This results in the transfer of childcare from the State to other dimensions – to the family/household as re-privatisation of care, to the market, widening the demand for private caregivers and CAIs, and to the NFP sector as unfulfilled needs driving community actions. As an actor, the State’s interaction with the market dimension, mostly through its reduced regulation, is linked to reproducing inequalities by not guaranteeing the service to those who are more vulnerable.

Second, the interactions between the market, family/household, and NFP indicate degrees of blurring between private and public domains regarding childcare. Following the changes in public support of childcare, mainly through cash transfer to families, we identified an increase in caregivers working in private homes. We frame this phenomenon within a long-term debate by feminist economics that care in the private realm conceals informality and exploitation due to barriers to regulate working relations within the domestic sphere.

Between the family/household and NFP, the blurring of domestic and public domains happens as women take their own children to be part of community-based on collective spaces and non-market logics, such as solidarity and reciprocity, organising work and collaboration. While community-based childcare provision may be seen as transferring responsibilities from the family to NFP spaces, the latter emerge predominantly due to unfulfilled basic needs that fall under the State’s responsibility. The predominance of women in structuring, functioning, and sustaining NFP initiatives conveys the weight of childcare on them, enhanced by precarious labour market participation and public support. While extreme needs are felt by families and communities, their weight is highly feminised as they are seen as women’s and mothers’ responsibilities (Carrion et al Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022, 22). Favourable collaborations happen between the family/household and NFP dimensions, mostly due to direct and indirect benefits for women participating in these collective spaces, such as meals, safety from gender violence, and empowerment. Even when women receive monetary compensation, they face constraints in getting another job as they depend on community-based and collective sources of childcare.

Third, and relatedly, we underline the importance of qualifying the interactions between family/household and State through choices around public childcare. Low-income women and families may face many challenges, yet they also exercise their decision of not utilising the public service. Reliance on family members, networks, and NFP spaces for childcare is connected to perceptions and assessment of (i) who should be responsible for raising children (mostly mothers), but also, (ii) the lack of trust in public services and the overall absence of services to address the needs of low-income women.

Limitations in public childcare provision impact families differently. For those with resources, this has increased the demand for private care in establishments and at home. The latter are difficult to regulate, allowing for exploitation and abuse. For rural, indigenous, and low-income communities, unpaid care work at home is bound to increase. While it is not possible to affirm there is a re-privatisation of childcare (Estrada Reference López Estrada2020; Carrión et al Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022), our analysis conveys an increased in-household burden for those with less resources. This movement may also be channelled via NPF initiatives.

As we sought to understand childcare through the four dimensions, looking at actors, institutions, and transferring of responsibilities, we circle back to our question: what are the gender consequences of childcare distribution in Mexico? Unpaid care work is a permanent and considerable phenomenon with significant negative impacts, especially among women with limited resources. As it exists in the family/household and NFP dimensions, it is particularly opaque, with restricted support and regulation from the State. We highlight three summarising points: i) gender norms and roles seem ubiquitous to all four dimensions conveying that women are seen as responsible for childcare; ii) even in countries without a strong welfare system, the State still occupies a central position, as ‘That which the state does not take on is left to markets, families or communities’ (Jenson and Saint-Martin Reference Jenson and Saint-Martin2003, 81); (iii) the current organisation of life has generated a crisis of care that cannot be satisfied by a sole actor (Orozco Reference Orozco2006; Carrión et al Reference Carrión, Reséndiz and Tejada2022; Fournier Reference Fournier2022).

Final remarks

We have synthesised childcare provision, distribution, and arrangement in Mexico based on Razavi’s diamond model. Our version of the model organises findings into (i) actors and institutions in each dimension and (ii) interaction between dimensions. Therefore, the disproportionality of our version of the diamond expresses the reduction of some dimensions, identified at each vertex, as well as their interaction with other dimensions. Conveying the existence of diverse and simultaneous forms of childcare in different dimensions directly challenges the traditional idea that care is women’s responsibility and that it should be carried out in the private sphere.

We have shown the consequences of a compromised public supply of childcare, which produces the transfer of childcare from the State to other dimensions – to the family/household, overburdening women, to the market, widening inequalities between families/women of different social classes, and to a limited NFP sector. Moreover, we make the case that simply increasing the existing public childcare would not – automatically and/or necessarily – satisfy the existing demand or alleviate pressure on women. Alternatively, community-based actions and NFP initiatives providing care have the potential to provide best practices for the State in effectively boosting vulnerable communities.

Three points are important. First, the reduction in public childcare services impacts heavily on women and families without resources. Second, the overburdening and transferring of obligations is linked to (and may reinforce) social perceptions that mothers should care for young children. Third, in both the family/household and the NFP dimensions, absorbing the demand of childcare is particularly opaque, with limited support and regulation from the State. These points support a clear need for policies, measures, and strategies tailored to the interdimensional character of unpaid childcare.

At a conceptual level, our study contributes to the development of models to analyse welfare and childcare distribution in the Global South, especially among societies that historically lacked the strong welfare regimes of some of their counterparts in the North. A key advantage resides in granting analytical space for the household and NFP sector – as well as their interactions – as constitutive dimensions and fundamental sources of childcare, as it has been in many countries in the region. We echo Razavi in avoiding a linear path of analysis in ‘which all countries move with an inevitable shift from “private” (family and voluntary) provision of care to “public” provision (by the State and market)’ (Reference Razavi2007, iv). Consequently, it is key to explore ways in which a society can better appreciate and leverage different sources of childcare provision and their articulation, and avoid reproducing or strengthening the idea of care as women’s responsibility.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ana Güezmes, Carmen Alvarez, Ramón Padilla, Sandra Huenchuan, and Miguel Castillo for comments to preliminary versions of this work.

Competing interests

No conflicts of interest. The authors take full responsibility for ideas and opinion in this manuscript. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations.

Magali N. Alloatti (she/her/hers). She holds a PhD in Sociology from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Brazil) in cooperation with UCLA (U.S.); a MSc in political sociology (UFSC) and a BA in sociology (UNL, Argentina). She specialises in migration studies, gender inequalities, and intersectionality. She was a consultant for the IOM/Brazil, and collaborated with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and United Nations Development Programme. She has studied and conducted research in the U.S., Brazil, and Argentina. In the last years, she has worked and lectured in Hamburg University, Bielefeld University, and Karlstad University. Her published work focuses on gender inequalities, austerity policies, COVID-19, and paid and unpaid work in Brazil, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Email: magalialloatti@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6747-4794.

Ana Luíza Matos de Oliveira (she/her/hers). Associate Economic Affairs Officer and gender focal point at ECLAC’s subregional office in Mexico City. Has a PhD in Economic Development from Unicamp, with a research internship at the Zakir Husain Center for Educational Studies (Jawaharlal Nehru University) and at the Lateinamerika-Institut (LAI – Freie Universität Berlin). Has a Master in Economic Development from Unicamp, with a research fellowship at the Université de Genève. Holds a Higher Diploma in Latin American and Caribbean Social Thought from CLACSO. Has a BA in Economics from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and was an exchange student at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Email: ana.matosdeoliveira@un.org. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9623-3305.