IntroductionFootnote 1

New atheism was a sociocultural phenomenon that emerged during the first decade of the twenty-first century. Centred principally on the United States, it played a key role in the construction of a wider atheist movement and attracted high levels of media and academic interest with its no-holds-barred approach to religious affairs. Research into the new atheism has stemmed from a variety of disciplines, including sociology (e.g. Amarasingham, Reference Amarasingam2010; Cimino and Smith, Reference Cimino and Smith2014; LeDrew, Reference LeDrew2016; Cotter et al., Reference Cotter, Quadrio and Tuckett2017), philosophy (e.g. Caputo, Reference Caputo and Martin2007; Johnson, Reference Johnson2013; Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2019), theology (e.g. Beattie, Reference Beattie2008; Haught, Reference Haught2008; Lennox, Reference Lennox2011), and political science (e.g. Kettell, Reference Kettell2013; McAnulla Reference McAnulla2014; McAnulla et al., Reference McAnulla, Kettell and Schulzke2018), but shares a number of common themes. Most work on the subject has tended to be critical, presenting new atheism as philosophically shallow and supportive of reactionary politics, and many studies have focused on its internal dynamics, centring on its leaders (typically Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens—collectively known as the ‘Four Horsemen’), its strategic debates, issues of identity and conflicts over representation and diversity (e.g. Cimino and Smith, Reference Cimino and Smith2011; Kettell, Reference Kettell2013). Many studies have also focused on the development of new atheism. Work here has explored the causal factors behind its emergence, the long-term trends within the wider atheist and secularist movement (e.g. Cimino and Smith, Reference Cimino and Smith2014), and the key features of its intellectual history (e.g. LeDrew, Reference LeDrew2016; Oppy, Reference Oppy, Cotter, Quadrio and Tuckett2017).

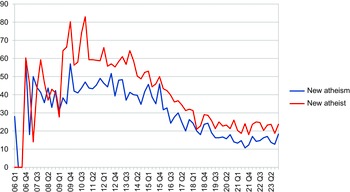

In recent years, however, the star of new atheism has waned. Public interest, as measured by data taken from Google trends, shows a marked decline from a high point between the end of 2009 and the start of 2014, with the number of internet searches on this topic falling thereafter. Search data from the U.S. and globally are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Google trends, quarterly averages (U.S.).

Figure 2. Google trends, quarterly averages (Global).

This downturn has led to claims that the new atheism has unravelled amidst a series of internal splits and divisions (e.g. Gilson, Reference Gilson2017; Torres, Reference Torres2017, Reference Torres2021; Milbank, Reference Milbank2022; Brierley, Reference Brierley2023). Much of the discussion around this decline, however, has taken place on blogs, social media and other online forums, and the topic has been largely neglected by the academic literature. This article aims to address this gap. In doing so it makes four key contributions. First, by focusing directly on the issue of decline, it addresses an aspect of new atheism that has thus far been overlooked in scholarly research, most of which has focused on longer-term patterns and trends (e.g. Cimino and Smith, Reference Cimino and Smith2014; LeDrew, Reference LeDrew2016; Cotter et al., Reference Cotter, Quadrio and Tuckett2017). Second, in accounting for this decline, the study makes a conceptual contribution by highlighting the role of ‘atheism’ as an empty signifier—a term or phrase that can be filled with varying meanings by different individuals or groups, but which ultimately lacks a fixed or stable signification. While this provided a unifying rallying point and facilitated political mobilisation during the formative years of the atheist movement, it also facilitated its fragmentation, proving unable to sustain disparate meanings once the movement began to grow in size. Thus, while existing research has highlighted internal conflicts within the atheist movement (e.g. Kettell, Reference Kettell2013; McAnulla et al., Reference McAnulla, Kettell and Schulzke2018), the case presented here offers an alternative theoretical explanation for why these tensions became so intractable. Thirdly, the paper adds to our conceptual understanding of new atheism by drawing on insights from social movement theory, focusing in particular on the idea of a social movement lifecycle. While a number of existing studies have also drawn on concepts from social movement theory, these are not typically used as the central organising framework (e.g. see LeDrew, Reference LeDrew2016), are often interwoven with other theoretical approaches (for instance, Cimino and Smith (Reference Cimino and Smith2014) combine aspects of social movement theory with theories of subcultures, media studies and sociological analysis), or focus on conceptual themes other than the movement lifecycle (e.g. Kettell, Reference Kettell2013). The fourth principal contribution of this study is that it seeks to link the internal dynamics of the atheist movement to the wider sociopolitical and cultural context, in particular to the rise of identity politics and an intensification of the culture wars in the United States. Within the existing literature, these factors have been relatively disconnected. For instance, LeDrew (Reference LeDrew2016) views new atheism as an ideological reaction to late modernity, but does not relate internal tensions within the atheist movement to the particular context of the United States. Similarly, Cimino and Smith (Reference Cimino and Smith2014) have argued that the culture wars were beneficial to the atheist movement, generating the sense of opposition needed for a viable secularist subculture to thrive (also see Taira, Reference Taira, Guest and Arweck2012).

The following sections chart the rise and fall of new atheism from within the context of the U.S. atheist movement, examining the phases of its development from formation to decline. They begin with an examination of the social movement lifecycle before considering the different phases of this cycle as they apply to the case of new atheism, showing how cultural and political dynamics intersected with, and exacerbated, a range of internal tensions around the meaning of an atheist identity. The article concludes by discussing the implications of these findings and points to some possible directions for future research.

The social movement lifecycle

Social movement theory brings together a range of conceptual tools for analysing the way in which social movements evolve, focusing on changes in their strategic and organisational behaviour over time (e.g. Christiansen, Reference Christiansen2011; Klandermans and van Stekelenberg, Reference Klandermans, van Stekelenburg, Huddy, Sears and Levy2013; Martin, Reference Martin2015; Almeida, Reference Almeida2019). While this embraces a variety of approaches, at its core social movement theory revolves around four intersecting themes. The first of these is the role of opportunity structures. These refers to the range of exogenous factors that impact the ability of a movement to mobilise and influence society. These factors can include political institutions, the nature of the party system, public policies and avenues for political and civic participation. Opportunity structures determine whether the political environment is favourable or hostile to achieving movement goals. The second core theme is resource mobilisation. This highlights the various resources that movements need to utilise in order to be effective, such as finance, personnel, media presence and moral authority. Resource mobilisation emphasises the importance of gathering and deploying these resources effectively if a movement is to sustain its activities, influence public discourse and bring about positive change. The third core theme is that of collective action frames. These are the narratives produced by movement participants in their attempt to define an identity, highlight grievances and articulate strategies for action. For a frame to be successful it must resonate with broader social values, enabling movements to recruit and mobilise supporters by constructing convincing narratives about injustice and the need for change.

The final core theme in social movement theory is the movement lifecycle. This concept has been devised by scholars as a way of outlining the key phases through which social movements tend to pass. While variations exist (e.g. Maher et al., Reference Maher2019) the typical cycle falls into four discrete stages: (1) Emergence—a preliminary phase where grievances are widespread, but where there exists little to no social organisation to address them, (2) Coalescence—where the rise of collective action to address these grievances leads to the construction of a social movement with clear leadership, goals and identity, (3) Bureaucratisation—a phase characterised by the growth of formalised organisational structures and strategies, and (4) Decline—where the movement either achieves its objectives, ceases to function or becomes absorbed into the institutional structures of the state (see Christiansen, Reference Christiansen2011).

In the past two decades, the dynamics of social movements have been significantly reshaped by the emergence of new digital technologies. As Bimber et al. (Reference Bimber, Flanagin and Stohl2005) highlight, the rise of the internet has dramatically reduced the costs of resource mobilisation, enabling decentralised forms of leadership and the rapid dissemination of information. This shift has allowed movements to bypass traditional gatekeeping institutions, spread their message and mobilise intellectual resources through a range of online spaces, such as blogs, social media and forums. This phenomena is described by Couldry (Reference Couldry2014) as the creation of a ‘myth of us’, where digital connections foster a sense of collective identity even in the absence of traditional organisational structures. By expanding social networks, online platforms can increase access to information, mobilise intellectual resources, and enhance both recruitment and engagement (also see Boulianne, Reference Boulianne2015). The effectiveness of these networks, however, is contested. Bennett and Segerberg (Reference Bennett and Segerberg2012), for example, argue that digital activism often relies on ‘weak-tie’ networks that are driven by individual expressions of identity rather than a genuine sense of collective belonging. As a result, ‘ideologically demanding’ collective action frames can exacerbate internal divisions, making movements more vulnerable to fragmentation. Digital technologies have also complicated the model of a movement lifecycle. The decentralised networks enabled by social media allow movements to sustain activity without developing formal bureaucratic structures, while the individualised and transient nature of online participation can lead to fragmentation and decline, bypassing traditional lifecycle stages.

This conceptual toolkit provides a useful way of understanding the rise and fall of new atheism. The study locates this within the wider context of the U.S. atheist movement, drawing on extensive materials produced by participants over the last two decades, including blog posts, talks, interviews, podcasts and videos. The analysis shows that opportunity structures, issues of resource mobilisation and struggles around collective identity were critical to the way in which the movement developed. It also shows that the trajectory of the atheist movement deviated from the conventional four-stage lifecycle. Rather than progressing linearly through phases of emergence, coalescence, bureaucratisation and decline, the path taken by the atheist movement was marked by periods of fragmentation and collapse following its initial coalescence. The following sections examine these stages—emergence, coalescence, fragmentation and collapse—in more detail.

Emergence and coalescence

The establishment of a U.S. atheist movement during the early years of the millennium was driven by a number of factors. The first was a cumulation of significant, long-running grievances. Many non-religious citizens (especially atheists) reported discrimination in areas such as housing, employment and health, alongside high levels of social stigma (Hammer et al., Reference Hammer2012). Polls repeatedly showed that a majority of Americans would not vote for an atheist president, and atheists featured consistently low on surveys of social trust, with one study famously ranking them less trustworthy than rapists (Gervais et al., Reference Gervais, Shariff and Norenzayan2011). Taken together, these factors created a sense amongst many non-religious citizens that they were facing what Mackey et al. (Reference Mackey2021, 861) describe as a ‘social identity threat’, ‘a feeling that one’s group is not valued or does not belong in a given context’.

These grievances were coupled with growing concerns about the negative impact of religion. The early years of the century saw ongoing attempts by religious groups to shape public policies in a range of areas, including restricting access to reproductive healthcare, imposing limits on sexual expression and pushing creationism (via notions of Intelligent Design) into the school curriculum. The dangers of religious violence featured strongly too, being vividly highlighted by the terrorist attacks of 9/11.

These issues were compounded by the significant social and political power of religious organisations. While the atheist movement emerged in a landscape marked by a plethora of non-religious cause groups, some of which (such as American Atheists and the Freedom from Religion Foundation) had been active for many years, the resources available to these groups, whether in terms of finance, personnel or media reach, were dwarfed by those possessed by religious organisations (Kettell, Reference Kettell2014). This reflected the broader religious landscape of the United States, where, in 2007, 78% of adults identified as Christian (although the percentage of adults formally affiliated with a Christian denomination was likely to be lower) (Pew Research Center, 2008). Meanwhile, just 16% of adults identified as religiously unaffiliated (ibid., 2024).

This landscape also reflected the recomposition of American society following the rise of the ‘culture wars’ from the 1950s. This refers to increasing levels of polarisation and conflict over social and cultural issues, particularly those relating to identity (such as race, gender and sexuality), often characterised by a tendency to frame disagreements in moral terms. Described by Hartman (Reference Hartman2015) as ‘a war for the soul of America’, these cultural conflicts had fuelled an increasingly bipartisan divide marked by falling levels of trust and increasing social atomisation, cleaving political allegiances along religious and secular lines and driving religious organisations to become more politically mobilised. Since the 1970s right-wing Christian groups had forged close links to the Republican Party, increasing their political influence (see Gorski, Reference Gorski2017; Mason, Reference Mason2018). Taken together, these developments had helped to create an opportunity structure that was highly disadvantageous for atheists to the extent that the first two decades of the millennium saw just one openly atheist member of congress (Wing, Reference Wing2019).

The rise of new atheism was in many respects a reaction to this situation. Initially finding life as a publishing and media phenomenon, with best selling books by Harris (Reference Harris2004), Dawkins (Reference Dawkins2006), Dennett (Reference Dennett2006) and Hitchens (Reference Hitchens2007), the new atheism attracted high levels of media attention, throwing a spotlight on atheist views and helping to mobilise non-religious citizens. While the category of ‘non-religion’ includes a variety of identity labels, and while the proportion who identify as atheists is comparatively small, the new atheism’s emphasis on atheism as a distinct identity helped to create a sense of community and shared purpose among many of those who rejected religious belief. At the same time, the opportunity structure was starting to shift with the growth of the internet. This impact of this new communications technology was dramatic, enabling non-religious groups and individuals to disseminate their ideas, form online networks and organise collectively in virtual spaces free from geographical constraints (Smith and Cimino, Reference Smith and Cimino2012). These included forums, such as the Infidel Forum (founded in 2004) and Atheist Nexus (2008), as well as a proliferation of blogs and social media platforms (the most notable of which were Reddit and YouTube) which provided a free resource for atheist content such as talks, debates and commentary. This brought together a multiplicity of loosely connected groups and actors without the need for an overarching organisational structure or formalised leadership (Kettell, Reference Kettell2013).

These developments were the foundational steps in the construction of a wider atheist movement. The process of turning grievances into an effective and coherent mobilisation effort requires a sense of group belonging and collective identity, with members who are committed to shared norms and values (Carvacho et al., Reference Carvacho2023). As Vestergren et al. (Reference Vestergren, Drury and Chiriac2018, 856) observe, ‘to create sustained commitment to collective action a social identity needs to be created with identity relevant norms for emotion, efficacy, and action, through within-group interaction’. This is described by Sani (Reference Sani2005, 1076–77) as a sense of ‘group entatitivity’, or ‘the degree to which a group is subjectively perceived as a singularity, as constituting a unified whole’. From the middle of the decade, this sense of common belonging was on the rise, producing a collective action frame based on the need to normalise atheism and secure equal rights and treatment for non-religious individuals. As Tom Flynn, Executive Director of the Council for Secular Humanism, wrote: ‘A movement was aborning, or at least being written about with feverish energy’ (Flynn, Reference Flynn2010). While this was not uncontroversial (Grothe and Dacey (Reference Grothe and Dacey2004, 50) argued that atheists needed ‘a public awareness campaign, not a liberation movement’) many saw the vehicle of a social movement as essential for achieving these objectives. As Jack Vance, writer of the blog ‘Atheist Revolution’, explained: ‘The reason an atheist movement is relevant or necessary has nothing to do with the definition of atheism; it has to do with the socially constructed meaning of atheism. Specifically, it has to do with how people are treated because they are atheists’ (Vance, Reference Vance2009).

To achieve these ends, atheists highlighted the need for promotional work and community engagement efforts to gather more supporters. Daniel Dennett, for example, called for ‘well-organized and well-publicized campaigns for health, justice, safety, environmental protection, etc. to rival the good works of the churches’ in order to ‘swell our ranks’ (Mehta, Reference Mehta2007). Hemant Mehta, writer of the blog, ‘The Friendly Atheist’ contended that ‘unless we can offer certain benefits that religions provide, minus the supernatural aspects, atheism is going to remain a hard sell for many people’ (Mehta, Reference Mehta2009). Here, atheists used a variety of methods, including talks and debates (many of which were broadcast online), advertisements on billboards and public transport, outreach efforts such as Atheists Helping the Homeless (founded in 2009) and a range of community building projects such as Camp Quest (founded in 1996 but embarking on an expansion programme from 2007) and the Atheist Film Festival (which ran from 2009 to 2014) (Kettell, Reference Kettell2014).

Atheists also drew on the lessons of earlier social movements to highlight the need for a show of numbers, arguing that this was necessary to normalise atheism and demonstrate that it was not the handmaiden of immorality it was often considered to be. The centrepiece of this approach was an ‘out’ campaign, created in 2007 by Elisabeth Cornwell, then Executive Director of the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science, which encouraged atheists to out themselves as a way of achieving greater visibility in U.S. society.Footnote 2 As Herb Silverman, President of the Secular Coalition for America, put it: ‘the most important thing an atheist activist can do is to come out of the closet. It worked for the LGBT movement, and it can work for us’ (Dietle, Reference Dietle2012). This approach reached its apogee in 2012 when tens of thousands of people attended a high-profile Reason Rally in Washington. The Rally was described by the organisers as ‘the largest secular event in world history’ and had the stated aim of unifying and emboldening secular supporters ‘while dispelling the negative opinions held by so much of American society’.Footnote 3

While these methods had broad support throughout the nascent movement, a number of strategic differences were also evident. Many of those identifying as new atheists argued that a confrontational approach, based on criticising and ridiculing religious beliefs, was also needed to promote social change. As PZ Myers, writer of the blog, ‘Phyrangula’, wrote: ‘The path we’ve taken in the past, the cautious avoidance of the scarlet letter of atheism, has not worked’ (Myers, Reference Myers2007). Or as Adam Lee, author of the blog, ‘Daylight Atheism’, claimed: ‘No broad social movement has ever achieved its objectives by sitting back and waiting for everyone else to come around’ (Lee, Reference Lee2012). Others, however, argued for a more consensual approach based on establishing common ground with religious groups and individuals, claiming that attacking religion would alienate potential supporters. Paul Kurtz, founder of the Center for Inquiry, described confrontational tactics as ‘a strategic blunder’ given the need to establish ‘a wider base of support’ (Nisbet, Reference Nisbet2010). Chris Stedman (Reference Stedman2012, 9) claimed that new atheists were ‘engaging in monologue instead of dialogue’ and described interfaith engagement as ‘the key to resolving the world’s great religious problems’. Others called for a mixture of approaches. Arguing that strategic diversity was a strength, David Silverman, then-President of American Atheists, maintained that ‘the movement will fail if we try to restrict it to a “one size fits all” approach’ (Dietle, Reference Dietle2012). Greta Christina (Reference Christina2007) argued that ‘different methods of activism speak to different people’, and called for a ‘multi-pronged approach to activism’ utilising a mix of confrontational and consensual strategies.

In many ways these developments were part of the normal course of the social movement lifecycle. Amenta et al. (Reference Amenta2010) note that a mobilisation of grievances is necessary for a movement to gain traction, but once a movement becomes established new challenges arise, prompting internal debates over which strategies should be pursued. As these debates intensify, movement participants tend to divide between those who prefer more dramatic actions and those favouring consensual methods. As Jung (Reference Jung2010, 41) writes, ‘it appears to be a common pattern across various social movements that radical factions put more emphasis on the importance of confrontational actions when moderate factions turn their core strategies to more active engagement in institutional politics’.

A more serious fault line emerged around the meaning of an ‘atheist’ identity. Supporters of an atheist movement argued that having a sense of shared identity was necessary for establishing group coherence and promoting common goals. As PZ Myers (Reference Myers2008) wrote: ‘If this New Atheist movement … is to increase its ability to influence the culture, being able to recognize our essential unity as a community is essential … A fractured group of hermits and misfits cannot change the world’. The process of constructing an ‘atheist’ identity involved debates around the values, practices and symbols that the movement ought to adopt. Yet it remained far from clear what a specifically ‘atheist’ identity might consist of. Some doubted whether the label ‘atheism’ should even be used at all given the negative connotations associated with the term. Daniel Dennett (Reference Dennett2003) argued for the alternative term ‘Brights’, while Sam Harris (Reference Harris2007) called for the atheist label to be abandoned altogether on the grounds that continuing to use it would condemn the movement to the status of ‘a cranky sub-culture’. Others, such as Richard Dawkins, had called on people ‘to grasp the nettle of the word “atheism” itself, precisely because it is a taboo word, carrying frissons of hysterical phobia’ (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2002).

The attempt to create an atheist identity encountered deeper challenges related to the term ‘atheism’. This label is open to a wide array of interpretations and has historically been defined in ways that cover a spectrum of views. These definitions range from viewing theism as a mere questioning of the existence of god(s), to a more assertive stance based on an overt denial of the existence of god(s) and a specific negation of theistic assertions (e.g. see Quillen, Reference Quillen2015). The political fluidity of the term complicated matters further, since atheism is compatible with diverse viewpoints and dispositions across the political spectrum, from progressive to conservative ideologies (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey2021).

During the emergence phase of the atheist movement this malleability proved to be a significant asset, allowing ‘atheism’ to function as an empty signifier—a term with vague and ambiguous content whose meaning can be supplied by individual participants (Quillen, Reference Quillen2015). In this context, the term ‘atheism’ served as a flexible container that accommodated diverse interpretations, beliefs and values. This inclusivity facilitated group mobilisation without compromising the overall sense of collective identity. As the movement matured and entered its second phase, however, the dynamics around an ‘atheist’ collective identity would become a source of deepening divisions.

Fragmentation and crisis

In the typical lifecycle of a social movement the phases of emergence and coalescence turn into a phase of bureaucratisation where formalised strategies and institutional structures come to the fore. The development of the atheist movement took a somewhat different trajectory, partly because it arose in a landscape filled with many long-standing grievances and non-religious cause groups, and partly because its online mode of organisation precluded the emergence of a formal organisational structure. Instead, the phases of emergence and coalescence turned swiftly into a phase of fragmentation and crisis, as debates about mobilisation became conflicts around the values, purpose and identity of the movement.

The turning of the decade saw new atheism reaching something of an apogee. The political opportunity structure, though still predominantly hostile, was now starting to look more favourable. The proportion of adults describing themselves as religiously unaffiliated had grown from 16% in 2007 to just under 20% by 2012 (Pew Research Center, 2024), and social attitudes towards atheists were showing signs of improvement. A Gallup poll in 2012, for instance, found that 54% of Americans were willing to vote for an atheist president, the highest level since the question was first asked in 1958 (Gallup, 2012). Other indicators of success, such as the increasing presence of atheist and secularist voices in public discourse, the significant growth of organisations like the Secular Student Alliance (which expanded its network from 129 campus groups in August 2009 to 328 by May 2012),Footnote 4 and legal victories against religious practices in public schools (such as Doe v. Indian River School District, 2011) also suggested that the movement’s goals were at least partly being achieved. Although new atheism in particular, and the atheist movement generally, had suffered a blow with the death of Christopher Hitchens in 2011, the idea of atheism as a social movement had firmly taken hold. The available resources were being effectively utilised, a variety of networks and online spaces were continuing to blossom, and a collective action frame around a discourse of civil rights had clearly taken root.

From this point, however, the problems began to intensify. Some (for example, Coyne, Reference Coyne2016) have argued that the subsequent decline of new atheism was due to its success in having made atheism more respectable. This view is consistent with the claims of classical social movement theory, but overlooks the internal divisions that were now growing within the movement. The greater social acceptance of atheism did not automatically translate into a decline in movement activism. Indeed, fragmentation and internal conflict, rather than a sense of accomplished goals, appear to have been the primary drivers of decline. Much of this stemmed from the breakdown of ‘atheism’ as an empty signifier. Partly this was due to issues of resource mobilisation, as strategic differences around the best way of expanding the movement and defining the direction that it needed to take started to sharpen.

These differences were exacerbated by an intensification of the culture wars following the 2008 financial crisis. The economic strains of the crisis produced an anti-establishment reaction across the country, creating an environment where identity politics and ideological purity became highly salient. Data from the Pew Research Center (2014), for instance, showed that the partisan gap on 10 key social and political values had almost doubled in the last ten years, rising from an average of 17.1 to 31.4 points, having barely changed in the previous decade (rising from 15.1 points in 1994). On the right, this shift was manifest as a reinforcement of conservative values and a backlash against liberal elites, running from the Tea Party to the nationalist populism of the presidential candidate, Donald Trump. On the left, the crisis led to increased activism around issues of social and economic justice as marginalised groups sought to address systemic inequalities around issues such as race, gender and sexual orientation (Gorski, Reference Gorski2017). These shifts were themselves part of a global surge in populist politics described by Fukuyama (Reference Fukuyama2018) as a ‘new tribalism’ in international affairs. Political struggles in democracies around the world were becoming decoupled from economic issues, focusing instead on themes of social and cultural identity. As Charnock (Reference Charnock2018, 6) put it, people’s personal identities were now becoming ‘increasingly bound up in their partisan affiliation’.

This heightened salience of political identities significantly hampered the attempt to construct a collective ‘atheist’ identity. Instead, by the middle of the decade two rival and increasingly polarised camps had emerged, each offering radically different assessments of the problems facing the atheist movement and prescriptions for how to address them. On one side were those, typically located on the left of the political spectrum, who wanted the movement to be more politically progressive, inclusive and diverse, and who pushed for an expanded form of atheist identity connected to social justice issues. The other side, typically consisting of conservative and libertarian atheists, subscribed to a far narrower (and in their view, politically neutral) definition of atheism and saw calls for a broader interpretation as an attempt to claim ownership of the movement for the purposes of promoting a subversive political agenda.

This fracturing gained pace as those on the progressive side of the movement began to draw attention to shortcomings in its racial and gender composition. Highlighting issues of resource mobilisation, progressives pointed to the fact that most leaders in the movement (even if such roles were largely informal) were white, male, heterosexual members of the intelligentsia, and claimed that atheist spaces such as conferences and online groups were not welcoming to minorities, especially women. These concerns were exacerbated by a growing number of allegations pertaining to misogynistic abuse and sexual harassment, some of which came to involve prominent figures within the movement (Winston, Reference Winston2014). Against this backdrop, progressives began calling for active measures to ensure that atheist environments were safe and to encourage greater diversity. This was seen as a necessary step in the development of the movement, simultaneously offering a route to attract more members and providing a means of tackling the problems posed by religion, many of which were said to be intersectional in nature.

Two high-profile flashpoints, in particular, brought these tensions to a head. The first, an event that came to be known as ‘Elevatorgate’, occurred in 2011 when a blogger called Rebecca Watson posted a video expressing her unease about having been propositioned in a lift at 4:00 am during an atheist conference in Ireland. The video provoked a misogynistic backlash, with many accusing Watson of exaggerating this situation for effect and of trying to promote a radical feminist agenda (Schnabel et al., Reference Schnabel, Pace, Berzano and Giordan2016). Amongst the more notable critics was Richard Dawkins, who remarked that Watson ought to ‘grow up, or at least grow a thicker skin’ (Myers, Reference Myers2018). Others were more prosaic. Railing against the movement ‘getting bogged down in this nonsense’, the YouTuber ‘Amazing Atheist’ (2011) attacked Watson, saying: ‘who fucking cares if you are uncomfortable in a fucking elevator for twelve seconds?’

The second flashpoint emerged the following year and centred on a schismatic attempt at fusing atheism with progressive politics, known as ‘Atheism Plus’. Responding to the ‘surge of hate’ that followed Elevatorgate, the progenitor, Jen McCreight, called for a ‘new wave’ of atheism’ that was more than ‘just a bunch of “middle-class, white, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied men” patting themselves on the back for debunking homeopathy for the 983258th time’ (Reference McCreight2012a). Instead, Atheism Plus focused on the intersections between atheism and social issues such as racism, sexism and homophobia. As McCreight put it (Reference McCreight2012b), ‘we’re more than just “dictionary” atheists who happen to not believe in gods … we want to be a positive force in the world’.

The creation of this new identity marker was welcomed by many (including those identifying as new atheists) who saw links between progressive causes and their opposition to religion, and who wanted to broaden the appeal of the atheism movement. As PZ Myers wrote (Reference Myers2012): ‘if we want to expand the movement … we need to recognize that social justice, equality, and fighting economic disparities must also be a significant part of our purpose’. In this context, Atheism Plus posed a challenge to established figures in the atheist movement who were said to have little interest in, or grasp of these wider issues. As Greta Christina (Reference Christina2013) put it: ‘Why should the people who are already in the skeptical and atheist movements … be the ones to decide which internal policies are core issues … and which ones are on the fringe?’ ‘Why’, she asked, ‘should the agenda get to be set by the old guard?’ Others took a harder line and called for those not espousing progressive values to be purged from the movement altogether. For Richard Carrier (Reference Carrier2012) Atheism Plus would enable atheists to build ‘a system of shared values that separates the light side of the force from the dark side’. Thus: ‘Everyone who attacks feminism, or promotes or defends racism or sexism, or denigrates or maliciously undermines any effort to look after the rights and welfare and happiness of others … should be marginalized and disowned, as not part of our movement’.

Conversely, many conservative and libertarian atheists saw Atheism Plus as a deviation from the core focus of the movement and considered it to be a hostile takeover attempt by left-wing activists—particularly those promoting a radical feminist agenda. The popular atheist YouTuber, ThunderF00t (2013), claimed that Atheism Plus was being driven by ‘professional victims’, a ‘harem of elite feminist whiners’ who were said to be ‘poisoning the movement’. In response, critics of Atheism Plus reasserted a narrow, ostensibly non-political view of atheism as a mere lack of belief in deities. The blog ‘Amplified Atheist’ (2012) described Atheism Plus as a ‘shockingly incompetent’ attempt to rebrand atheism that ‘only serves to twist and misuse the word away from what it really means’. The philosopher Massimo Pigliucci (Reference Pigliucci2012) attacked the new project, arguing that ‘atheism is not a social or political philosophy in its own right, it is a simple metaphysical or epistemic statement about the non existence of a particular type of postulated entity’.

These events highlighted the diverging priorities within the atheist movement, exemplifying the way in which its internal tensions mirrored the intensifying culture wars in American society. The backlash from right-wing atheists also prefigured a narrative shift towards a new collective action frame based on the idea that politically correct, left-wing activists were trying to capture the movement and shut down anyone who disagreed with them. Richard Dawkins, for example, decried what he saw as ‘a climate of bullying, a climate of intransigent thought police’ coming from certain sections of the movement (Winston, Reference Winston2014). Similarly, Jerry Coyne, author of the blog ‘Why Evolution is True’, rejected claims that the movement had a misogyny problem and accused progressives of being ‘ideologues … a pack of baying hounds’ (Reference Coyne2014). Alongside this, many were now asserting a form of atheist identity aligned to the ideals of conservative politics. In 2015, following a snub the previous year, American Atheists began trying to forge links with right-wing political groups by attending the Conservative Political Action Conference. The journalist and radio host, Jamila Bey, became the first atheist activist to address the conference, calling on Republicans to engage with the growing numbers of the religiously unaffiliated, describing them as ‘millions of voters that we cannot afford to ignore’ (Mehta, Reference Mehta2015). In 2017 the Republican Atheist movement was launched with the aim of showing that ‘atheists can have conservative views’ (Atheist Conservative, 2017).

Collapse

The latter half of the decade proved to be a period of mixed fortunes for atheists in the United States. On a variety of metrics, atheism was better positioned than ever before. A raft of networks and communities had been established and new groups (such as Women of Colour Beyond Belief, set up in 2019) were being created. Atheist prejudice, though still high, was slowly declining—the proportion of Americans willing to vote for an atheist president reached its highest ever level by the end of the decade, at 60% (Saad, Reference Saad2020)—and the number of adults identifying as religiously unaffiliated was continuing to rise, hitting a record 32% in 2022 (Pew Research Center, 2024). At the same time, however, the hope of building an atheist social movement with a sense of common values, identity and purpose was disintegrating.

The principal reason for this lay in the psycho-emotional dynamics of collective identity formation. While a sense of common identity is required for a group to effectively function, the norms and beliefs that bind a movement together are not static but require ongoing efforts to reaffirm and reproduce (Della Porta and Diani, Reference Della Porta and Diani2006). This process creates the potential for division. If the core identity or values of a group come to diverge from what many believe to be its central mission then this can generate a loss of collective identity, a decline in commitment and increased schismatic intentions (Bennett and Segerberg, Reference Bennett and Segerberg2012). As Catellani et al. (Reference Catellani, Milesi, Crescentini, Klandermans and Mayer2006, 207) write, a schism can occur ‘when one faction within the group sees the position of another as not only different from its own but also as subverting the very nature of the group’. At this point compromise becomes impossible since ‘the disagreement is over the essence of identity, and when people disagree over what their group is about, they are likely to split’. Or as Sani (Reference Sani2008, 718) explains: ‘A schism is normally triggered by the perception that a change (i.e., either the adoption of a new norm or the revision of an old norm) endorsed by the group majority denies the group identity and constitutes a rupture with its historically sedimented essence’.

By the middle of the decade the atheism movement was reaching such a point. The blogger Adam Lee (Reference Lee2014) remarked that atheists were currently ‘wracked by infighting’, and as Jack Vance (Reference Vance2017) observed, the lack of a shared identity meant that the idea of an atheist social movement could no longer be said to exist ‘in any meaningful sense’. Richard Carrier (Reference Carrier2018), noting the growing sense of ‘tribalism and division’, declared that atheism was ‘collapsing as a movement’. These splits also exacerbated the resource mobilisation issues facing the movement, undermining its coherence and weakening its effectiveness, producing a vicious downward spiral. Infighting and ideological clashes absorbed a huge amount of time, energy and attention, making it more difficult to maintain a unified public presence and diverted resources away from the core goals of opposing religious influence and fighting for atheist civil rights. These divisions also made it harder for the movement to attract new recruits and to mobilise existing members. A highly visible manifestation of these troubles had been seen in 2016 when a poorly attended follow-up to the Reason Rally was widely considered to have been a failure (e.g. Moore and Kramnick, Reference Moore and Kramnick2018).

As these internal conflicts within the atheist movement grew ever-more fractious, the dynamics of the culture wars intensified further under the Presidency of Donald Trump. The increasingly polarised political climate, where social and cultural issues took centre stage, now made it virtually impossible for atheism to remain a unifying identity. Trump’s pursuit of a populist-nationalist agenda sharpened social divisions and created a greater widening in the ideological gulf between left and right. Conservative and libertarian atheists, many of whom shared Trump’s nationalist sentiments, clashed with progressives calling for social justice, inclusivity and intersectional feminism (Egan, Reference Egan2020). Mirroring this broader cultural realignment, issues of identity now took precedence over traditional ideological divides. As Croft (Reference Croft2021) observed, by the latter part of the decade ‘the lines between religion and nonreligion, and even conservatism and liberalism, [were] becoming less important compared with the line between the “woke” and the “anti-woke”’.

At this point the original collective action frame of the movement, which had focused on normalising atheism and securing civil rights for non-religious citizens, was superseded by a pair of irreconcilable and mutually antagonistic narratives. For those on the progressive wing of the movement, the fault was said to lay with atheists on the right who were unrepentantly propagating a culture of racism and misogyny. From this perspective, the atheist movement had been degraded by bad actors whose sole interest was in advancing their own careers by stirring up hate and promulgating bigotry. Much of this was also said to have stemmed from the leading figureheads of the movement. Richard Dawkins was accused of making misogynistic, Islamophobic and anti-transgender remarks on social media (for which the American Humanist Association later withdrew his 1996 Humanist of the Year award) (Greenesmith, Reference Greenesmith2021). Sam Harris was accused of indulging racist and misogynist tropes, including calls for the racial profiling of Muslims at airports, promoting racial theories of intelligence on his podcast and claiming that atheism was more attractive to men because it lacked a ‘nurturing, coherence-building extra estrogen vibe’ (Boorstein, Reference Boorstein2014).

Against this backdrop the view of the progressives was that the atheist movement had degenerated into splits and divisions at the very moment when it should have been adopting a strategy of engaging with minority groups to draw in members and create a network of more diverse and welcoming social alliances. As Greta Christina (Reference Christina2015) observed: ‘It seems that increasingly, we have two atheist movements … There are the ones who care about social justice; the ones who want to make organized atheism more welcoming to a wider variety of people … And there are the ones who don’t care’. Or as PZ Myers put it, new atheism had turned into ‘a shambles of alt-right memes and dishonest hucksters mangling science to promote racism, sexism, and bloody regressive politics’ (Reference Myers2019a). The most influential voices within the movement, he said, had ‘aimed the ship of atheism straight into the Trumpkin swamp’ (Myers, Reference Myers2019b). Striking a similar tone, the blogger Marcus Ranum (Reference Ranum2019) declared that the atheist movement had ‘turned into a shit-show of cheesy grifters and attention-whores’.

In contrast, the narrative constructed by the conservative and libertarian strand was that the atheist movement had been taken over by left-wing activists who had abandoned all pretence to rational thinking and had instead become obsessed with promoting doctrines of political correctness. Worse still, the significance of this transition extended beyond the confines of the atheist movement and was now thought to pose an existential threat to the very fabric of the nation. According to those on the right, progressives were no longer able to defend the core values of Western civilisation, which were said to be under threat from enemies around the world, ranging from authoritarian regimes in China and Russia to a resurgent Islamist threat in Europe, amply demonstrated by terrorist attacks in France, Belgium and the UK (Hamburger, Reference Hamburger2019). Issues widely supported by progressives, such as calls for greater gender and racial equality, were roundly denounced for being ‘woke’—a term that, for many, had come to replace ‘atheism’ as an effective empty signifier and provided a new rallying point for political mobilisation.

For some, the dangers of social justice activism were deemed to be so severe that it was now thought necessary for right-wing atheists to form an alliance with their erstwhile religious opponents in order to confront the evils of woke ideology. The philosopher, Peter Boghossian (Reference Boghossian2019) claimed that the atheist movement had been ‘ripped apart’ by proponents of a ‘woke memeplex’, later adding (Reference Boghossian2021) that wokeism was: ‘A religion [that] has metastasized within and consumed the atheist movement’. In the same vein, Michael Shermer claimed that Atheism Plus had led to a systematic ‘purging’ of the atheism movement by the far left, and denounced ‘wokeism’ as a neo-Marxist form of religion (Atheists for Liberty, 2021). David Silverman (shortly after being fired as President of American Atheists amidst allegations of sexual harassment) claimed that the ‘religion of wokeism … had infected the atheist movement—shutting down all forms of dissent’ (Minds Podcast, 2019) and later (Silverman, Reference Silverman2023) called for the promotion of a ‘Secular Christianity’ that would bring like-minded atheists and religious citizens together as ‘stalwarts against wokeism’. Thomas Sheedy, the President and founder of Atheists for Liberty, described proponents of Atheism Plus as ‘infiltrators’ and called on atheists from the right to fight ‘[t]his mind virus called social justice’ (Atheists for Liberty, 2021). Similar views were expressed by Ayaan Hirsi Ali, once considered to be the ‘fifth horsewoman’ of new atheism. Announcing her unexpected conversion to Christianity, Hirsi Ali declared that Western civilisation was facing an existential threat from ‘the viral spread of woke ideology’, and warned that attempts to counter this with the force of secular reasoning and rational argument had failed. As such, the only credible answer was ‘to uphold the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition’, which provides the human freedom needed for secularism and market-based institutions to thrive. ‘[A]theism’, she claimed, was ‘too weak and divisive a doctrine to fortify us against our menacing foes’ (Hirsi Ali, Reference Hirsi Ali2023).

Conclusion

The emergence of new atheism in the early 2000s attracted considerable media and academic interest. While existing research has explored its history, internal dynamics, conflicts and leadership, the reasons behind its decline remain largely unexamined. The purpose of this study has been to address this gap. In doing so, it makes four key contributions. First, by focusing on decline it explores an overlooked aspect of the new atheist phenomenon, drawing attention to the role of internal and external pressures in shaping its trajectory. Second, it highlights the crucial role of ‘atheism’ as an empty signifier, showing how this initially unifying concept ultimately proved unable to accommodate divergent political viewpoints and ultimately contributed to the fragmentation of the U.S. atheist movement as a whole. Third, it uses the conceptual framework of the social movement lifecycle to chart the mechanics of its decline. In contrast to the traditional four phase model, the U.S. movement moved rapidly from coalescence to fragmentation and decline. Fourth, the study links the internal dynamics of the U.S. atheist movement to broader social trends, particularly the rise of identity politics and an intensification of the culture wars.

In its emergence and coalescence phases, the U.S. atheist movement effectively deployed its available resources to combat the challenge of a hostile political environment, capitalising on the attention given to new atheism and levering internet technology to develop a collective identity centred on securing civil rights for atheists and reducing the influence of religion in American politics and society. In this, the movement benefited from the flexibility of the label ‘atheism’, which allowed atheists with divergent political views to unite under a common banner. However, as the movement matured and as the need for a more clearly defined identity came to the fore, this unity became increasingly difficult to sustain. Divergent views on how best to grow the movement exposed clear differences in the core values and strategic orientation of its members, leading to a growing split between progressive atheists advocating for social justice causes and right-wing atheists who argued for a narrower view of atheism. These tensions were exacerbated by an intensification of the wider culture wars in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, which further heightened the salience of partisan identities. The rhetoric employed by both sides of the atheist schism, particularly the use of terms like ‘woke’ and ‘social justice warriors’, closely mirrored the language and framing of the broader cultural conflict, sharpening ideological divisions within the movement and undermining any remaining attempts to forge an atheist collective identity. This rupture ultimately led to the movement’s decline. As these divisions widened, the two opposing sides of the movement became increasingly hostile, fracturing it beyond repair.

The rise and fall of new atheism has important implications for scholars conducting research into non-religious groups and social movements. As this study shows, social movements can follow alternative developmental paths and deviate from the typical phases of a movement lifecycle. In this case, the progression of the atheist movement from emergence and coalescence to fragmentation and decline illustrates an alternative trajectory, adding to our understanding of the different ways in which movements can evolve. The study has also shown that the success of social movements is contingent on a variety of factors, including the ability to forge a coherent collective identity, navigate the complexities of identity politics and adapt to shifting sociopolitical contexts. The deviation of the U.S. atheist movement from the typical social movement lifecycle, its reliance on an unstable empty signifier and the adverse effects of the culture wars, highlight the challenges faced by movements based on non-belief and point to a number of avenues that scholars might fruitfully explore. Research into the strategies employed by atheist and secular organisations in the wake of this decline could usefully examine the ways in which groups have sought to maintain relevance, rebuild alliances and adapt to changing social and political landscapes. In a similar vein, comparative analyses of the trajectories taken by atheist and secular movements in other parts of the world could seek to identify patterns in their development, challenges and outcomes, providing valuable insights into the influence of cultural and political forces. Examining the way in which non-religious groups navigate these challenges would deepen our understanding of their dynamics and contribute to the broader field of social movement studies.

Steven Kettell is a Reader in Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick. His research interests are centred on British politics, the politics of secularism, non-religion and the role of religion in the public sphere. He is the co-founder and executive editor of the journal British Politics.