In 2016, Judith Pollmann published an article in which she argued that historians of early modern Europe would do well to exploit more actively the potential of the thousands of local chronicles that Europeans wrote between 1500 and 1850. Local chronicles are chronologically organized accounts of events in the author’s community that usually cover a broad range of topics. Most of these texts were not written with a view to publication in print, but were manuscripts circulated among the literate middle and upper strata of early modern towns and villages. Few were published in the lifetime of their authors. Since the nineteenth century, some of them have been edited and published, but across Europe thousands of local chronicles remain in manuscript, scattered across local archives and libraries.Footnote 1

In her article, Pollmann proposed that rather than seeing local chronicles only as a form of historiography, as was customary among the medievalists who have been the most active students of this genre, they might also be approached as ‘archives’ in which early modern contemporaries collected information on a range of topics that they considered useful for future reference. Although the titles which they gave to such collections varied, and authors made their own selection of what knowledge they considered useful, chroniclers shared an interest in local politics and history, crime, prices, public space and natural or cultural events that they deemed remarkable.

Among early modernists, chronicles have long been understudied. After a surge of scholarly interest in the genre in the nineteenth century, and the publication of many editions, local chronicles were soon found to be too subjective for the taste of many modern scholars. For students of the self, the texts seemed unsatisfactory because they did not privilege the feelings of the authors. And while most urban historians have always continued to use them as a source of local colour, as well as to fill ‘gaps’ in the urban institutional archives, early modernists working on historiography considered them as a rather archaic genre that did not merit serious study. Scholars working on England, for instance, found evidence that by the late seventeenth century, serious intellectuals looked down upon the genre, and deduced that it had lost traction.Footnote 2 For this reason, it went long unnoticed that local chronicles continued to be written in large numbers well into the nineteenth century.

However, from the 1990s their very subjectivity began to attract the attention of scholars who are interested in the socio-cultural aspects of urban life.Footnote 3 In Germany, they began to be studied over the longer term. James Amelang was the first historian to study them in large numbers as a lens onto the world of artisans.Footnote 4 Others have been using them as a window on popular literacy, on religious change, or to consider experiences during the Age of Revolutions.Footnote 5 Yet the potential is greater. Chronicles are one of the few genres of narrative European text that remained both ubiquitous and stable throughout the early modern period. Most manuscript genres that have been used to study the individual engagement with change, such as diaries, letters, commonplace books, travel accounts and livres de raison, evolved so much under the influence of new literary conventions, developments in knowledge cultures and social changes that they are difficult to compare over time. Chronicles have changed far less. This may be because it was a literary practice that developed and survived informally, as a local cultural practice that was shared across Europe but for which no new published models were to hand. But however that may be, Pollmann hypothesized that this manuscript genre remained stable enough for it to be used as a baseline for comparisons over time and space, for instance for research into the reception of new media and new knowledge, or into changing political horizons. Erika Kuijpers, at VU University in Amsterdam, suggested that such an attempt should be made through the creation of a searchable digitized collection of texts. In 2017, Pollmann and Kuijpers were awarded an NWO (Dutch Research Council) grant to put that idea into practice in a pilot project about the early modern Low Countries that was conducted between 2018 and 2024 at Leiden University and VU Amsterdam. With a research team consisting of historian Carolina Lenarduzzi, computational linguist Roser Morante and Ph.D. candidates Theo Dekker and Alie Lassche, as well as many volunteers and student-assistants, we created a digitally searchable corpus of 204 texts in 308 volumes, 106 (177 volumes) of which had never been transcribed or published before.Footnote 6

The collection was used by the doctoral students in the project to research two topics that are especially relevant for the history of knowledge. Alie Lassche developed a computational method to research the evolving information landscape of the authors: what sources authors were using, and how new media affected the content of chronicles. She was, for instance, able to show that authors throughout the period relied heavily on oral sources, and that they cited publications by the authorities far more often than pamphlets (which were mentioned primarily as deplorable texts that other people believed in). Chroniclers in the Dutch Republic relied on newspapers significantly more than those in the Southern Netherlands. She also demonstrated that new categories of information appearing in the public media were adopted by chroniclers as new topics that were worth recording.

Theo Dekker successfully studied how chroniclers used their collections to reason about price developments, epidemics and meteorological phenomena, showing how they weighed the merits of arguments, and used both old and new explanations simultaneously. Together, Dekker and Lassche have proven that a collection of chronicles is indeed a viable tool to research the reception of cultural change, as well as the experience of political turmoil, war and religious change.Footnote 7

In the current article, and gratefully using the insights gained by Lassche and Dekker, we want to discuss what the project has taught us about the social, religious and public profile of chroniclers, and explore what this tells us about local chronicling as an activity. First, we will discuss the methodological choices we made when creating the collection. While ours is by no means the first major digitization or transcription project of early modern sources from the Low Countries, most such projects concern existing series of manuscripts that were created for institutional purposes. Our chronicles project was different, in that we had to create the collection as well as digitize it. Since it is also not straightforward to define what is, and what is not, a chronicle, we believe it is useful to share the insights we gained in the process. The second objective of this article is to discuss what we have learned about the social, religious and public profile of chroniclers and thus about chronicle-writing as a cultural and social practice.

Creating a corpus of local chronicles

Collecting a corpus of local chronicles began with the fundamental question of how we define chronicles. In the most basic sense, chronicles are chronologically structured records of events. The practice is referenced both in the Old Testament and in Ancient Rome, but exists all over the world. In medieval Europe, chronicling initially became one of the main genres in which dynastic and ecclesiastical history was written. Its practice in European towns is documented first of all in Italy, where cities commissioned chronicles to document their origin, legal foundation and political structure, as well as military feats. As the practice grew, members of ruling urban families began to commission manuscript copies that were customized to highlight their family’s contributions, and as early as the fifteenth century other city-dwellers too began to keep such records. By 1500, the practice had spread to towns in the Iberian Peninsula, the Holy Roman Empire, France, the Low Countries and England – and was eventually even adopted in villages, where both parish priests and other local literate people took up the practice. In German-speaking lands and the Low Countries as well as in southern Europe chronicling remained in vogue at least until the mid-nineteenth century. Thousands of local chronicles can still be found in archives and libraries across the European continent.Footnote 8

Although in all these areas, variants of the word ‘chronicle’ were used to describe local chronological records of this type, other descriptors were also frequently applied – there are chronological records of local events that authors themselves called ‘journals’, ‘annals’, ‘memoirs’, ‘commentaries’, ‘histories’ and ‘diaries’.Footnote 9 Many authors also used these terms interchangeably. Sometimes, archivists and librarians have assigned yet other descriptors to such texts. This meant that our collection was never going to include just texts that called themselves ‘chronicles’, but that the net had to be cast much more widely.

At the same time, not all chronicles were suitable for our purposes. First, we excluded family chronicles, texts that were primarily intended to record family events or the feats of family members and lack the focus on public affairs. That is not to say there was no personal information in local chronicles – authors did occasionally include personal details, and increasingly did so as time went on. Moreover, some authors used one and the same notebook in which they recorded both their chronicle and some personal or household information. But to qualify for inclusion in our corpus, the chronicle should focus on events in the community.

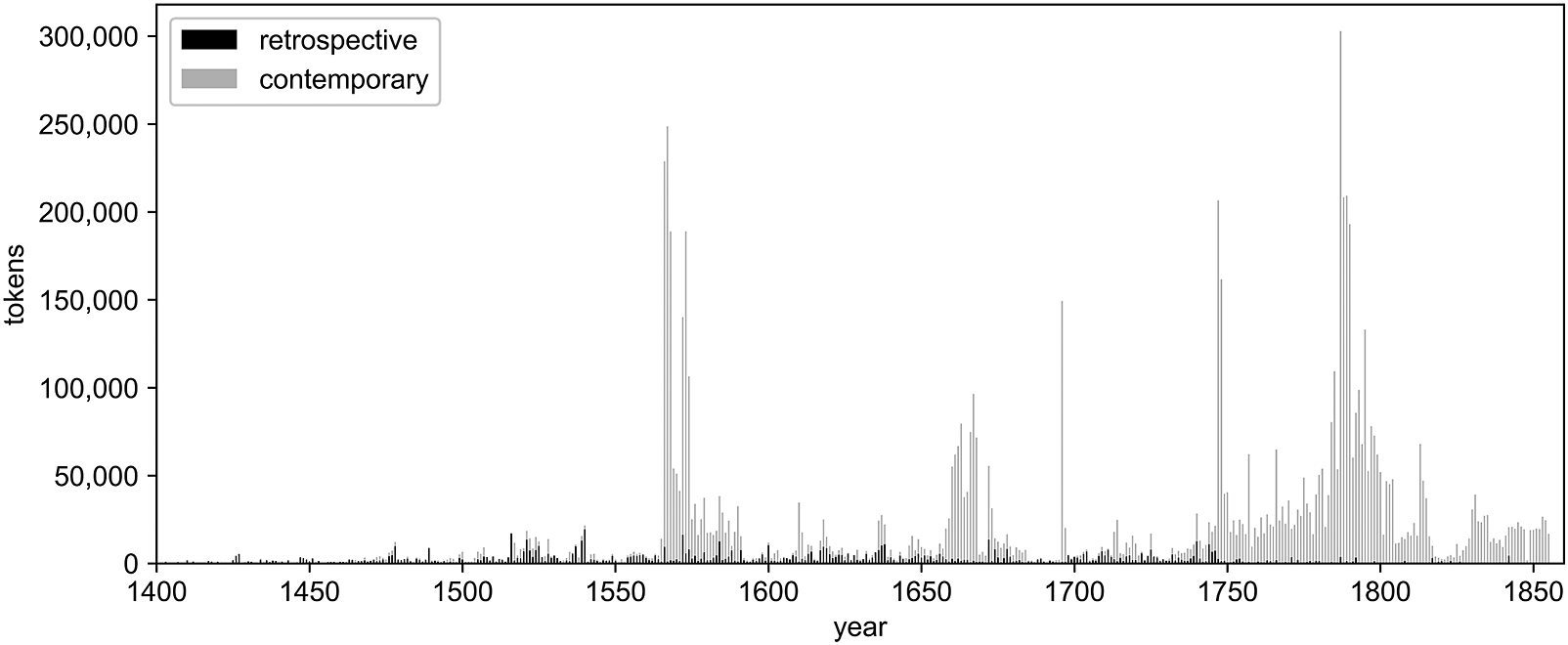

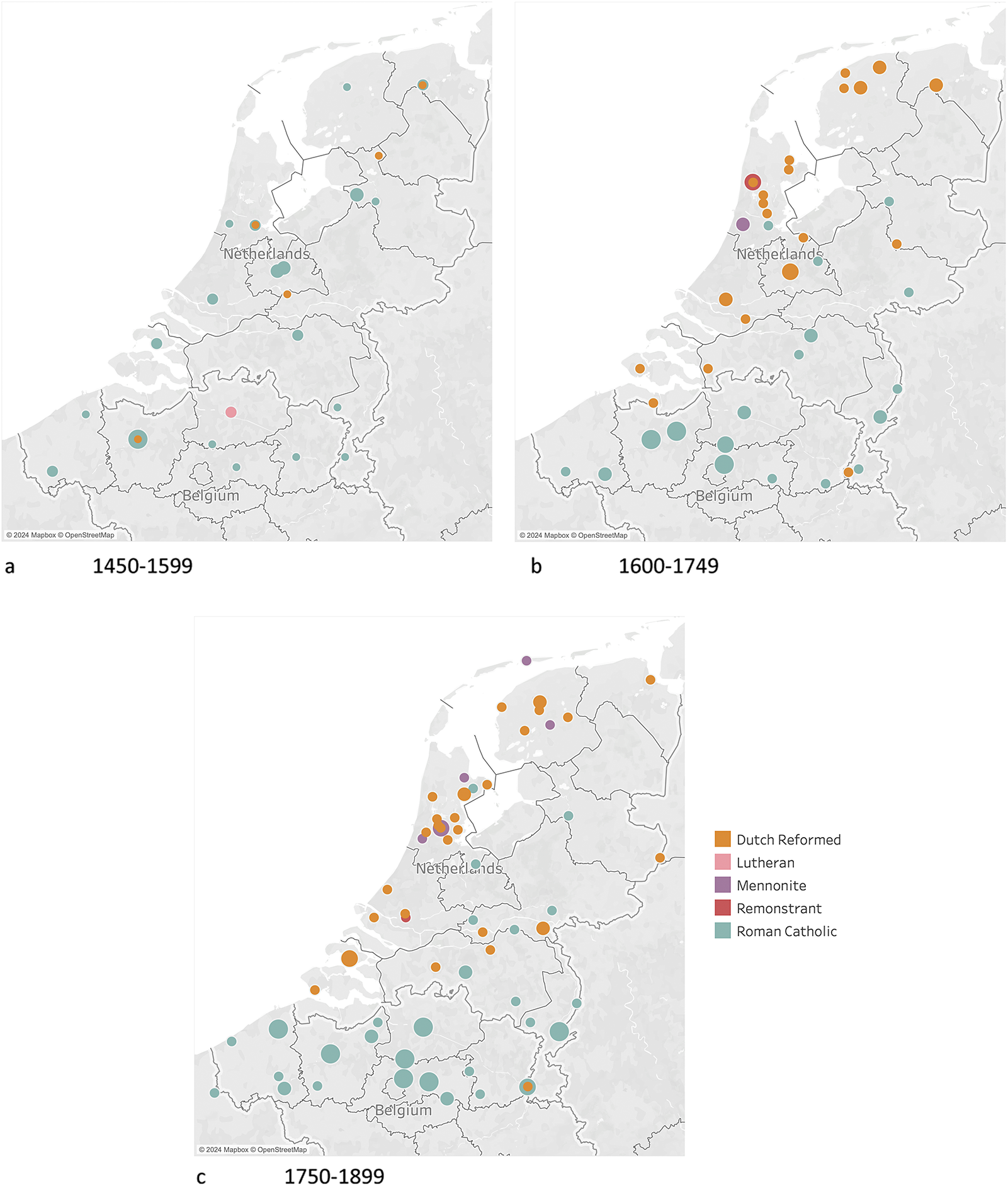

Secondly, we also deselected regional and national chronicles – texts which were more often written for publication in print, and by semi-professional historians, who were usually more interested in events in the past than in the present. Finally, we decided to focus on texts that not only covered local history, but that also discussed events in the (adult) lifetime of the authors, and were written contemporaneously to at least some of the episodes they described (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Word count per year based on a selection of 121 chronicles.

Light grey = text written about events that occurred during the lifetime of the chronicler.

Dark grey = written in retrospect.

Although the local texts we studied were very varied, the genre is quite distinctive – they often bear the name of the local community in the title or preface, might contain images and maps of the community, and speak about the community as ‘us’ or ‘we’. Insofar as they report on events beyond the community, they tend to do so because they had a local impact.

In the Low Countries, chronicles were written in Latin, French, Dutch and Yiddish. After the sixteenth century, when some authors still wrote in Latin, the vernacular was the language of choice. In order for our corpus to be machine searchable, we also decided we could only include texts that were (mainly) written in Dutch.Footnote 10 This meant that the French-speaking parts of current day Belgium are not represented in the collection.

When writing our grant application, we had made a basic inventory of available texts that we knew of from our own earlier research, and on the basis of earlier lists made by colleagues in Belgium and the Netherlands.Footnote 11 We estimated that around 100 local chronicles had at some point or other been edited and published or transcribed for local archives or historical associations. Some of these editions were already available on searchable digital platforms such as DBNL, the database for literary texts in Dutch, or on the websites of local archives. As a first building block for our corpus, we asked DBNL to digitize another 80 titles for us. This proved more complex than anticipated, mainly because of copyright issues. Although all living editors and their publishers proved willing to co-operate, it was difficult to trace some of the copyright holders, especially in Flanders. Some other texts proved unsuitable because the quality of the editions was poor, or because the editors had been too selective, or had rewritten rather than edited the texts. In all, this part of our corpus now includes 98 texts in existing editions – mostly, but not all, word-by-word transliterations of the original manuscripts. Many of the texts that had already been edited concerned events or periods seen as historically important, notably the Dutch Revolt and the Age of Revolutions. We hypothesized that among the unpublished manuscript chronicles, there might be more chronicles that were written in peacetime, by people of lesser social status or by those who were recording more everyday events. To capture these voices, we aimed to collect another 100 texts across the Low Countries that had not been transcribed or published before – we hoped for a good regional spread, as well as authors from different social strata – chronicles written by women or in the countryside were especially welcome.

We used a variety of strategies in our search. First, we searched the digital inventories of the provincial archives in the Netherlands and Belgium for (variants of) words such as chronicle, annals, journal, history and diary and we went through the inventories of manuscripts in library collections. We did the same for local archives where we knew or suspected that there might be a rich potential harvest. Mechelen and Rotterdam, for instance, were both known to have had a rich chronicling tradition, and the same was true for the Zaanstreek, the proto-industrial region north of Amsterdam. This yielded a list of potentially interesting texts, mostly kept in the libraries or ‘miscellanea’ collections of archives. Secondly, we targeted institutions that are known to keep large collections of chronicle-like texts. In Belgium, the Royal Library in Brussels, the University Library in Ghent and the collection Goethals-Vercruysse in the State Archive of Kortrijk proved especially rich. Because older published manuscript catalogues had listed historical texts and chronicles separately, they sometimes proved more informative and efficient to use than the digital catalogues. Finally, we also published a short article in the Archievenblad, the main professional medium for archivists in the Netherlands, in which we solicited suggestions.Footnote 12

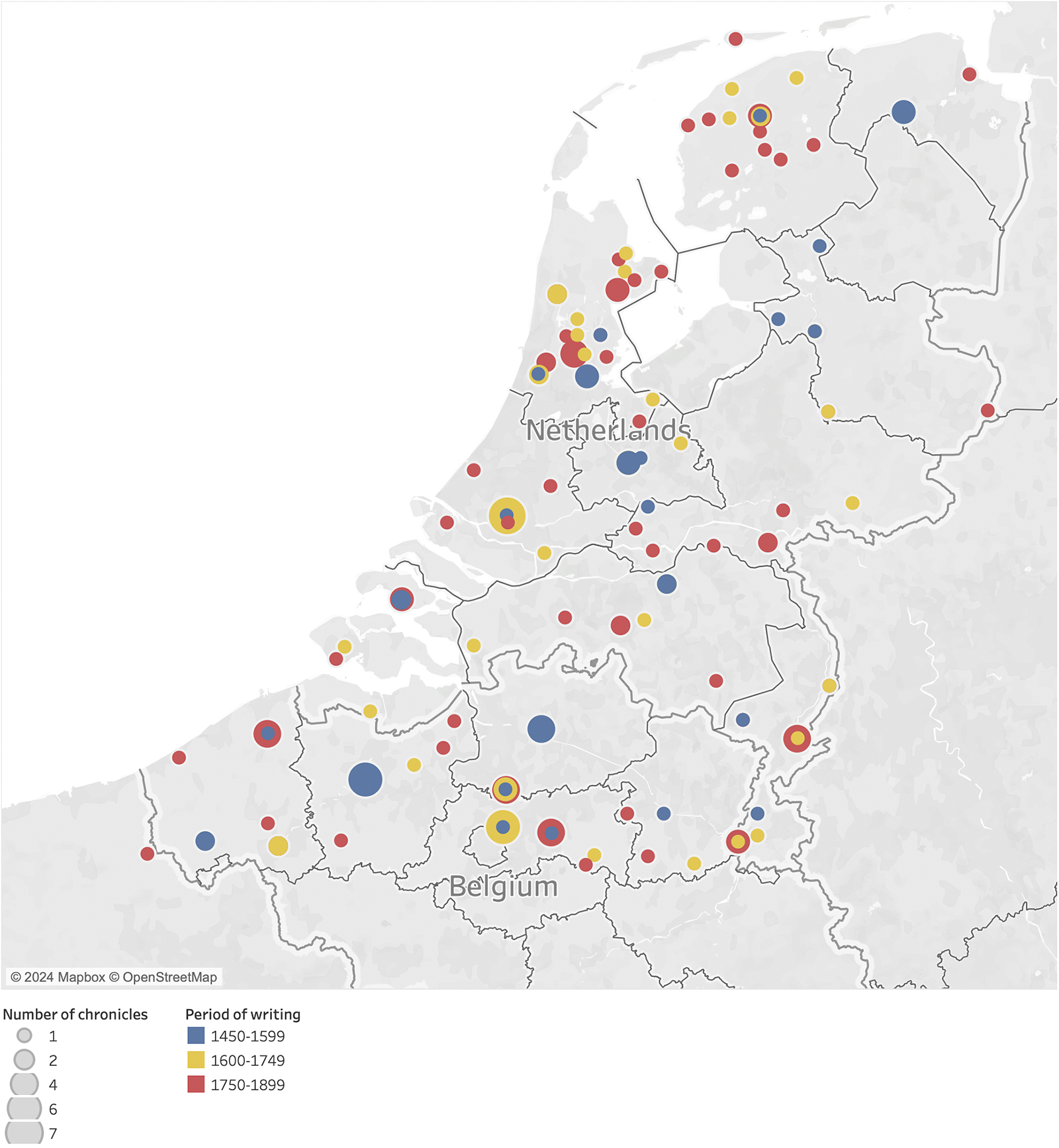

In this way, we were able to add 106 unpublished chronicles to our collection (a total of 177 manuscript volumes), that were sourced from 39 different archives and libraries, and 3 private collections. Although we created a larger corpus than we had anticipated, certain categories are under-represented. Thus, it is notable that, with a few sixteenth-century exceptions, we have no noble authors in our collections. One possible explanation is that nobles were more interested in chronicling family history. Yet it is also possible that if we had systematically searched private archives, more texts might have come to light. The same is true for chronicles by parish priests that may remain in parish archives. Geographically, too, there is some unbalance, in the sense that not all regions are equally covered, for example the north-eastern provinces of the Northern Netherlands are under-represented (see Figure 2). This may have to do with lower levels of urbanization and population density in this region. Finally, some texts also escaped our notice because they were written by authors who wrote in Dutch but who lived across the borders.Footnote 13

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of local chronicles in our text corpus.

Transcribing the corpus

When we first discussed our ideas for this project in 2016, the results of handwritten text recognition (HTR) programmes were still unsatisfactory. With character error rates of 10 per cent or more, most users would prefer to simply transcribe a text instead of correcting it. Yet, at the moment we submitted our final grant application in 2017, these error rates had dropped dramatically and we decided that we should make use of the Transkribus application that was being developed by the European funded READ project by a consortium of research groups from all over Europe, headed by the University of Innsbruck, and that has continued as the READ-COOP SCE, a co-operative company since July 2019.Footnote 14

To successfully use handwritten text recognition, we had to train an HTR model for each author, that is to say it was necessary to feed the computer around 15,000–30,000 words of manually transcribed text, as a basis on which the computer might teach itself to read the rest. To make the manual transcriptions, we relied on the help of volunteers, whom we attracted by creating a project on an existing crowd sourcing platform in the Netherlands, VeleHanden (Many Hands), that was developed by the Picturae company as an additional service to the archives who commissioned them to digitize their collections. In designing our VeleHanden project, we teamed up with the project Alle Amsterdamse Akten that was indexing the Amsterdam notarial deeds on VeleHanden but was considering using Transkribus to make the deeds full-text searchable. Both for them and for us, Picturae/VeleHanden integrated the Transkribus webtool in their user interface, allowing the volunteers to enter transcriptions that could be used for training HTR models.Footnote 15

As soon as volunteers had transcribed about 15,000–30,000 words of a hand manually, we started training a model for automatic recognition through the Transkribus system, by combining our own transcript with general models for early modern Dutch handwriting.Footnote 16 The results are good: usually we achieved character error rates of 3–6 per cent. Volunteers then corrected the automatically generated transcript. In a second crowd sourcing project on VeleHanden, volunteers annotated the texts by adding labels for the dates, named entities, page numbers, copied text, the inclusion of printed matter, images, tables and lists, and margin texts. A small group of selected volunteers subsequently also annotated the sources of information the chroniclers used.Footnote 17 Curation finally involved the creation of a database with all relevant metadata on the authors, the manuscripts and the content of the chronicle, allowing us to analyse the spatial and temporal coverage of our corpus as well as to chart a number of qualities related to the authors and texts. The analyses that we offer in the rest of the article are based on this collection.

As a small team, with only five years’ funding, we were unable to check the transcriptions of almost 34,000 scans including textual annotations by ourselves. Much of the correcting was done by volunteers whom we selected and invited for that task. Even so, the corpus is not consistent in the use of capitals and punctuation, and quite a few transcription mistakes remain. Nonetheless it has already become a valuable resource not only for our own research but also for others – we have given early access to the data to many of our students, a number of Ph.D.s and more senior colleagues. The transcripts are also a good starting point for future initiatives to publish more sophisticated editions of single chronicles that deserve a wider audience.

The survival of chronicles

Our aim in creating the collection was to get a good spread, across the period, across the Low Countries and across the social spectrum. Although we have succeeded reasonably well on all three counts, we do not want to argue that this collection is representative of the actual historical production of chronicles. This is for several reasons. First, we believe that some chronicles had a better survival rate than others because of their content. Chronicles written in periods that were deemed important by later generations, such as the Dutch Revolt or the Age of Revolutions, have stood the test of time better than others. At the same time, some people destroyed documents that they later found to be embarrassing, or that reminded them of positions they had once held but now abandoned.Footnote 18 We have found traces of this in our collection. One of our chroniclers, Jan Kluit from Brielle, burned his volume about the year 1786 because he feared it would incriminate him as a supporter of the defeated Patriot Movement. Later, when the coast was clear, he rewrote the records from memory.Footnote 19 Likewise, it is probably no accident that in the chronicle of Augustijn van Hernighem (c. 1540–1617) only the volume about the contentious end of the Calvinist Republic in Ypres is missing.Footnote 20 Moreover, the fate of chronicles was also determined by the setting in which they were written. Chronicles written by Catholic parish priests often remained in their parishes and chronicles written in convents also had a good chance of survival. Town secretaries often passed on manuscripts to their successors, and in the course of our period some cities began to collect chronicles themselves.Footnote 21 We only know of many texts because they were copied or continued by others. The notes that Nicolaes De Smet wrote on his ‘beloved Lokeren’ in the late sixteenth century were transmitted through the work of a local coppersmith and other successors in the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, as was the work of baker Jan Gerritsz. Waerschut from Rotterdam.Footnote 22 In this sense, many early modern chronicles continued in the medieval traditions that have been so well studied before.Footnote 23

Families also took care of manuscripts. Sons, brothers and wives sometimes continued the texts, or made sure they would pass into the right hands. Thus, in 1567, Philip van Campene continued the chronicle of his deceased brother Cornelis, and it was Ghent beguine Francisca van Quickenborne, who after 1808 passed the chronicle of her father, pickle-maker François, to Edouard Callion, who was to copy and continue the account to 1835.Footnote 24 By contrast, the two chronicles written by Zacheus de Beer (1739–1821), lock keeper in Spaarndam, have been preserved in the archive of the home for old men in Haarlem where he spent his last years, perhaps because he had no children to come and collect his belongings.Footnote 25 While most towns in the Low Countries had arrangements to keep civic records safe, manuscripts that were written in villages may have been more vulnerable. Certain areas of strategic importance, such as Flanders and the Meuse region, also suffered so much military depredation that many texts may have been lost.

Finally, political change had an impact on collections. Around 1580, for instance, Calvinist regimes in Flanders sold off the possessions of local convents they had sequestered. When Ypres chronicler Thomas de Raeve discovered that in such a sale of convent goods, his compatriot Arnoldus Bosluijt had acquired ‘a large manuscript chronicle, which had been written over a hundred years ago and containing many particularities concerning the city of Ypres…my heart burned to buy it, because I had for a long time been planning to write a chronicle of the early foundations of the city’. Bosluijt refused to sell, but eventually proved prepared to swap the chronicle for a relic of Saint Godelieve ‘studded with silver’ that De Raeve had bought in the same sale.Footnote 26 Convent collections came up for sale again after 1773, when the Jesuit order was disbanded, and especially after the French conquered the Austrian Netherlands in 1794 when important manuscript collections were dispersed. During the French regime, local archives were often badly damaged and neglected. In the early nineteenth century, inspired by a revived interest in national history and a new generation of historian-archivists, the collection of local material became a matter for the authorities of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.Footnote 27 After independence, in 1830, the Belgian state continued this policy, and many manuscripts passed from the hands of private collectors into local libraries and archives, or into the institutional collections of the new state. The city archive of Ghent, for instance, bought dozens of chronicles, which were subsequently transferred to the city’s university library.Footnote 28 In the Netherlands, local archives and libraries had not been so badly affected by the French regime, and fewer chronicles made their way to the markets. Most of them remained with provincial and local collectors and institutions.Footnote 29 This probably explains, for instance, why the Royal Library in Brussels owns a much larger collection of local chronicles than the Royal Library in The Hague.

Profiling the chroniclers

The sample of authors in our collection can neither claim to be representative of all chroniclers, nor of all chronicles that have survived. Nevertheless, it is an exceptionally large, varied and thus useful sample, that can help refine our knowledge of the practice of early modern local chronicling. When we began our project, we hypothesized that chroniclers were mainly male city-dwellers from the middling and higher ranks of urban society. Yet we already knew of some women chroniclers and some rural authors, and considering that literacy levels in the early modern Low Countries were relatively high, it was to be expected that there were more to be found. We were keen to find out whether the social profile of the authors changed over time. Was chronicling as attractive to Catholics as to Protestants, and did this change? We also wanted to know what role the authors’ occupations and public profiles played in the decision to start chronicling, and their access to non-public information.Footnote 30 Was this a genre that ‘democratized’ and if so, did it lose its appeal to higher-class or intellectually motivated authors?

What can we say about these questions now? Around 20 per cent of our authors were anonymous, so all our knowledge about these chroniclers comes from their texts. Occasionally these are informative about the world of the authors. The corpus includes two texts from eighteenth-century Maastricht, for instance, that were clearly written by people who served in the local garrison.Footnote 31 Sometimes it was possible to deduce the identity of the author through a flyleaf (such as with Gilles Voocht in Ghent) or because the authors frequently referred to themselves or their family in the third person, as did Guillaume Baten in Antwerp.Footnote 32 Yet because chroniclers focused on local events, the authors usually offer only very limited information about their own life. They often avoided the words ‘I’ and ‘me’, except in reported speech. Instead, they usually opted for a rather terse prose style, with short entries, that were intended to create a factual, and thus also objective and authoritative, impression.Footnote 33 Although our information on some chroniclers is thus very limited, we have nevertheless gathered a great deal of information on many of our authors that allows us to make a more fine-grained analysis of their social and cultural profile.

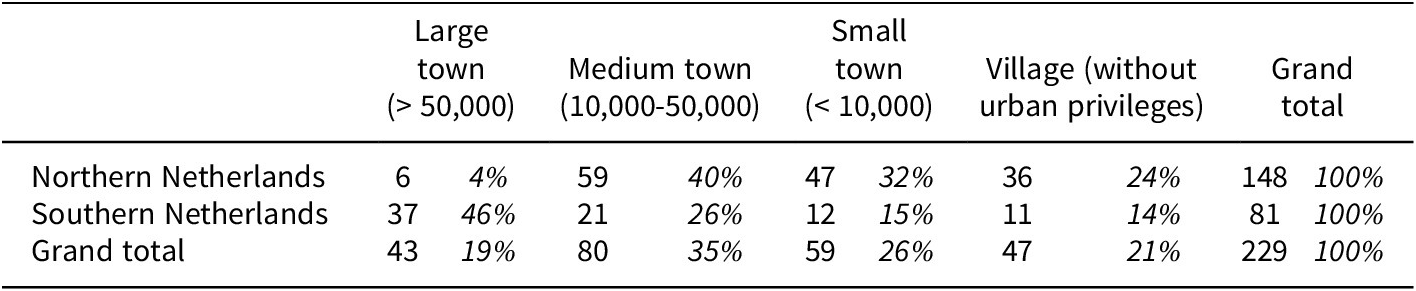

Place

Our assumption that chronicling was a typically urban activity seems to be largely correct. Of the chronicles in our corpus 79 per cent were written by townspeople. Almost half of the chronicles from the Southern Netherlands are from the three major cities Antwerp (11 authors), Brussels (11 authors) and Ghent (15 authors). The Northern Netherlands by contrast, especially the coastal provinces, are characterized by a large number of smaller towns which form a highly urbanized zone, interconnected by a dense network of water ways. Here, the majority of chroniclers lived in medium and smaller towns (see Table 1). Over a quarter (26 per cent) of all authors came from a smaller town of fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, of which most had fewer than 5,000 inhabitants. Still, a significant number of the chroniclers, 21 per cent, lived in a village, by which we mean places that had no urban privileges and therefore no walls, usually no jurisdiction of their own and no representation in provincial councils. Another definition of a village is that most of the inhabitants live from farming or fishing. The places we have counted as a village meet both these criteria. Chronologically, only eight of the rural chronicles date from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the majority stem from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is hard to tell what the cause of this modern bias is. Possible explanations are that in rural areas the survival rate of chronicles was lower, and/or that literacy levels were initially lower than in the cities.

Table 1. Location of chroniclers according to town size

Gender, age and marital status

While the majority of our authors were men, we also identified 14 chronicles written by 16 female authors, 11 of them nuns. In line with our aim not to include any institutional texts, the chronicles written by these nuns focused on local events rather than monastic history, and resembled other local chronicles in style and content. Of the non-religious female authors, only one was a practising Catholic, the otherwise unknown Maria Helena van Loosen from Roermond.Footnote 34 The other four authors were devout Protestants from the Northern provinces, and they were all writing in the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. This suggests that by that time chronicling had emerged as a practice that was considered appropriate for women in Protestant circles.Footnote 35

While we did not do genealogical research on all authors, it is clear that almost all authors about whom we have information were married – a sign that they had enough income to set up households of their own. It also implied they were not very young; men in the Low Countries tended to get married in their late twenties. It is difficult to be precise about the age at which our authors began their chronicles, but we know when 119 authors finished writing, on average they did so at age 58, with the youngest finishing at age 22 and the oldest at 98.

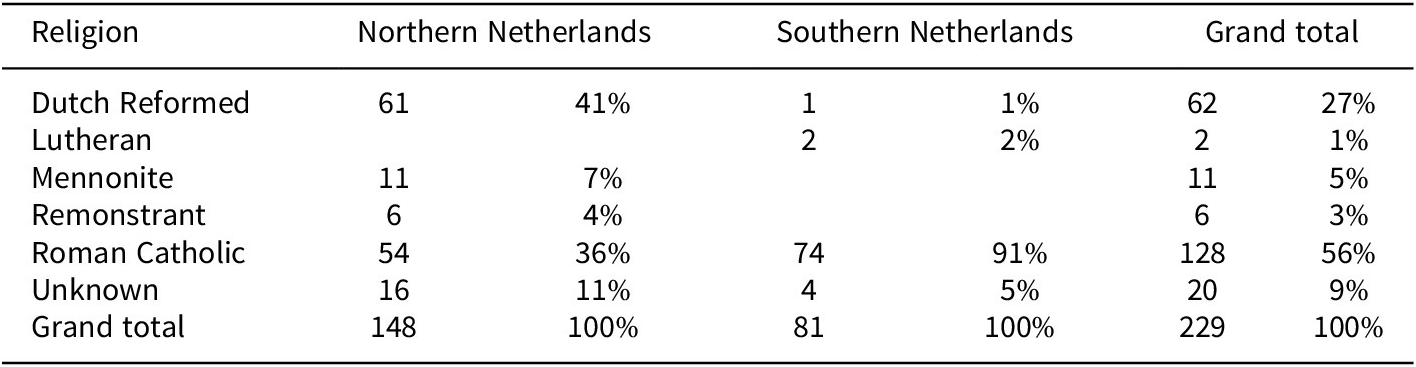

Religion

A second issue to consider is that of religion, and its relation to chronicling practices. Our collection enabled us to challenge an old assumption about the cultural differences between the various confessions, i.e. that early modern Protestants were more prolific vernacular writers than Catholics. This assumption is based on the widespread but mistaken idea that Catholic culture did not encourage reading and writing among the laity.Footnote 36 In a Low Countries context it also reflects the idea that in the Habsburg Low Countries, censorship had a stifling impact on vernacular writing.Footnote 37 However, if we look at the relation between religion and chronicling, we can conclude that, clearly, a vernacular Catholic writing culture existed in both the Southern and the Northern Netherlands and among both clergy and laity.Footnote 38 As to the clergy, we already pointed out above that lay and regular clergy wrote in a medieval tradition of institutional record-keeping. This probably explains why our collection includes twenty-four chronicles written by (lower) clergy and monks and nuns, compared to only four by Protestant ministers. Another explanation is that local Catholic priests tended to stay in place, and both male and female religious usually spent their entire lives in one particular village or city. By contrast, Reformed ministers usually began their career in village churches, and worked their way up to the much better-paid urban posts. Hence, they were less tied to one locality, and perhaps less likely to produce texts about local history and local affairs.Footnote 39

The religious background of most of the chroniclers was either known or could be established with an acceptable degree of probability (see Table 2). We have no inkling of the religious background of only 9 per cent of the authors. As may be expected, there is a striking difference between chroniclers in different regions. Of the chroniclers from the Southern Netherlands, modern Belgium, the vast majority, 91 per cent, adhered to the Catholic religion, a percentage that remained stable over time (see Figure 3 a–c). Apparently their religious convictions were serious since most chroniclers used a recognizably ‘Catholic’ vocabulary far more often than strictly necessary – such as the frequent use of the abbreviated adjective ‘H.’ (for ‘holy’) – and almost always spoke of the clergy and the church with reverence. Moreover, supernatural events or extraordinary phenomena were generally interpreted through a Catholic lens.

Table 2. Confessional background of chroniclers

Figure 3. Religious denominations of chroniclers divided in the long sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The high percentage of Catholics in the Southern Netherlands is unsurprising since from around 1585, when the Habsburgs reconquered and ‘reconciled’ with their rebellious Netherlandish subjects, most Protestants were faced with the choice of leaving the area or converting. Many decided to leave. The Southern Netherlands were quickly recatholicized and became a bulwark of Counter-Reformation Catholicism.Footnote 40 Before the Dutch Revolt, support for Protestantism in Flanders and Brabant had been notable, especially in the larger cities, and our corpus reflects this. It is no accident that the only Flemish Reformed author in our collection, Gillis Coppens, wrote in Ghent and that the only two Flemish Lutherans wrote chronicles in Antwerp: Godevaert van Haecht and Jan van Wesenbeke. Gillis Coppens, writing during the years when Ghent was a so-called ‘Calvinist Republic’, was a moderate supporter of Calvinism.Footnote 41 Local, political and religious ‘troubles’ prompted Van Haecht in 1565 to take up his pen.Footnote 42 Chronicler and civil law notary Jan van Wesenbeke recorded the (news of the) rapidly succeeding events between 1567 and 1580 in and around his hometown.Footnote 43 The 1560s to 1580s were a time when many Catholic authors, too, decided to keep a record of public affairs.Footnote 44 In (religiously) turbulent times, people are more likely to write down their experiences and their interpretation of events around them, in order to give meaning to the times in which they live, or to process traumas they have suffered.Footnote 45

Until 1600, the vast majority of the authors in the Northern provinces of the Low Countries also remained adherents of the old church, albeit in the second half of the sixteenth century the number of Protestant authors began to rise quickly (see Figure 3 a–c). The Catholic predominance in this period is not surprising, since the Reformed church that became the ‘public church’ gained ground only very slowly between 1573 and 1580,Footnote 46 with few people becoming full-fledged members.Footnote 47 Moreover, in the Dutch Republic, from the late sixteenth century onwards, a substantial group of believers emerged who were not communicant members of any particular church, even if they might have attended services and mostly had their children baptized.Footnote 48 These so-called liefhebbers (or amateurs) could be found among both Reformed and Catholic churchgoers. Until at least the second half of the seventeenth century, the Republic had a relatively large number of people who ‘shopped’ between the various denominations, sometimes attending one church, sometimes another. These people apparently did not feel strongly about a specific church, which might explain why some chroniclers do not reveal any clues about their religious beliefs.Footnote 49 This may also explain why we do not know the religious backgrounds of 11 per cent of the North Netherlandish chroniclers. This percentage is considerably higher than in the Southern Netherlands, where Catholicism was the state religion until 1794.

As of 1600, the religious background of the Northern authors in the corpus reflects the informal religious pluralism of the newly proclaimed Dutch Republic. While the Reformed church was the privileged church, dissenters were tolerated, although they were not allowed to openly profess their religion. With the caveat that within the Dutch Republic the percentages of the various denominations differed considerably per region and per period, our corpus roughly reflects the actual religious map.Footnote 50 Reformed chroniclers accounted for 41 per cent of the total number of authors, but we do not know how many of them were actual members of the Reformed church, or mere sympathizers. The numerically largest group of dissenters, the Catholics, comes a close second with 36 per cent. Many of these lived in the ‘Generality lands’, Catholic areas in current-day Limburg and North Brabant that the Republic conquered in the 1620s and 1630s. Authors from these provinces account for almost 45 per cent of the total number of Catholic authors in the Republic (see Figure 3 a–c). But even taking this into account, it is clear that the Catholics were as prolific in the production of chronicles as were the Protestants.Footnote 51

At some distance from the Reformed and Catholic authors come the chroniclers with a Mennonite (7 per cent) and Remonstrant (4 per cent) signature. Since the Mennonites were geographically concentrated in the north-west of the Dutch Republic and our corpus includes a relatively substantial number of chroniclers from these areas, Mennonite authors are somewhat over-represented, especially as of the 1650s.Footnote 52 Still, Mennonites appear to have been active chroniclers.

While most authors were clearly devout Christians, religious themes predominated in the chronicles only at times of great politico-religious upheaval. We have already noted how the religious and political changes of the Dutch Revolt prompted many authors to start writing. We find the same mechanism at work at the end of the eighteenth century, when first the political and religious reforms of Joseph II, and secondly the French takeover triggered Catholics in the Habsburg Netherlands to chronicle their concerns. Our corpus reflects this surge in chronicle-writing, which found a counterpart in the Dutch Republic, which in the 1780s was beset by a violent political contest between ‘patriots’ and ‘Orangists’, adherents of the stadholderly family. In 1795, former ‘patriot’ opposition politicians joined forces with the French Revolutionary armies and proclaimed a Batavian Revolution, that instituted the separation of church and state, and so put an end to Protestant domination. There, too, religious changes made by the French were a source of anger, and sometimes also a motive for writing.Footnote 53

Social status

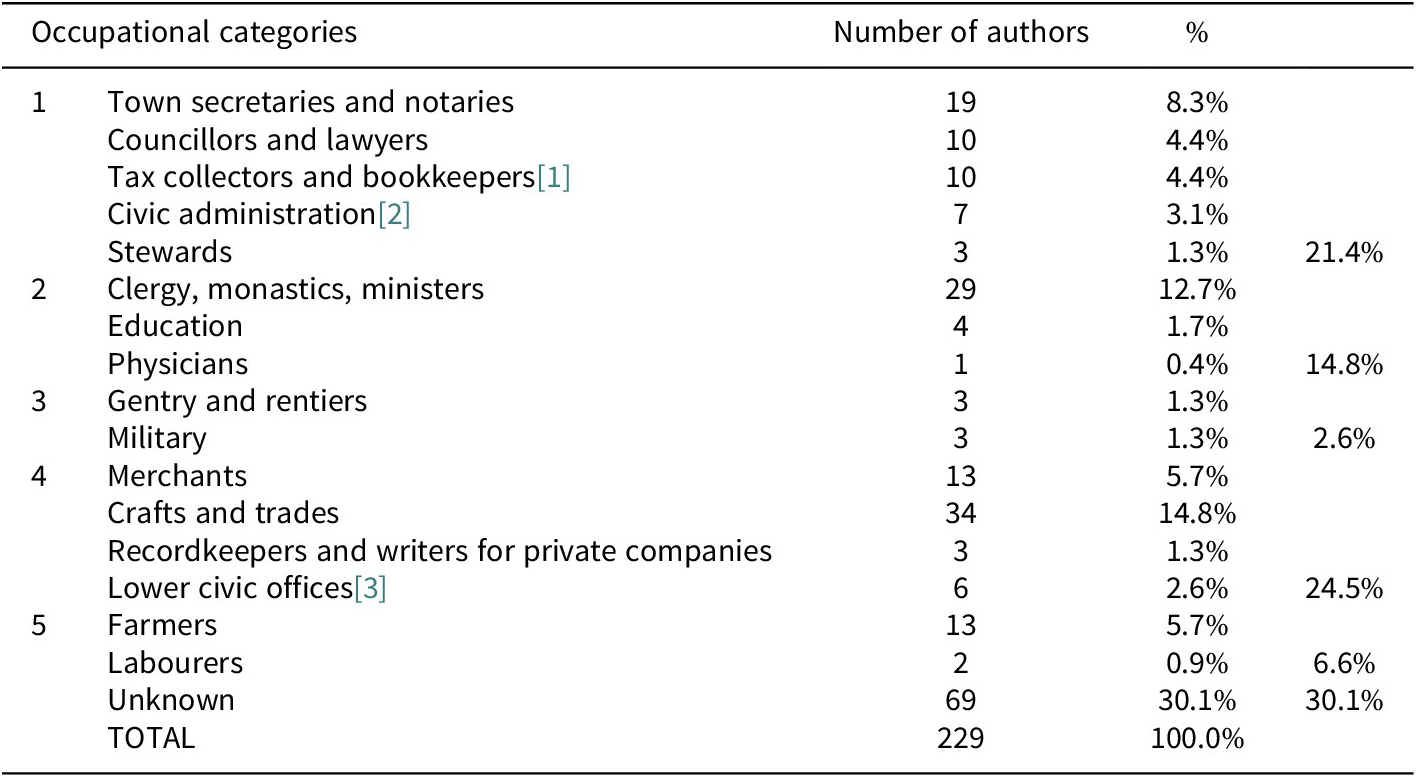

We managed to ascertain the occupational background of 70 per cent of the chroniclers but were unable to trace the line of work for sixty-nine authors. In Table 3, we have divided the chroniclers’ occupations into five categories, enabling us to draw some broad conclusions about the social profile of our authors (see Table 3).

Table 3. The occupations of chroniclers

Notes:

[1] The Tax collectors and bookkeepers category included people who collected specific excises, supervised markets, mills and the dues paid there, and acted as bookkeepers of public or ecclesiastical bodies. Titles included: Collecteur van het recht en hessenhuis Antwerpen; Gaarder; econoom van het Bogaardenklooster; Collecteur van de accijns op turf en kolen, boekhouder van het korenboek en vendumeester van de vis op de Grote Zeevismarkt; kassier van de ontvanger van het Brugse Vrije; hoofdgaarder van de gemenelandsmiddelen in Brielle; zoldermeester; Hoofd fabrieken en molens aan de Roer.

[2] In this category we find clerks, assistant-secretaries, surveyors and bailiffs, as well as ‘wijkmeesters’, who supervised quarters within towns: klerk/assistent stadssecretaris; landmeter; klerk van het register; ambtenaar bij het Hof van Friesland, eerste deurwaarder van de Kamer in den Rade van Friesland.

[3] The remunerated civic offices in this category include roles such as city drummer, ‘father’ of the house for the insane and victims of pestilence, carillonneur and organist, and corn-inspector (korenmeter; binnenvader van het pest- en dolhuis; stadsbeiaardier; organist; koster; trommelslager, executeur, stadsmajoor).

What stands out is that employees of local or regional governments, civil servants, were particularly motivated to start chronicling. They are (mostly) represented in the first category. As Table 3 shows, it was particularly town secretaries who in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries often combined the role of secretary with that of a notary, who wrote chronicles. These town secretaries were generally well educated, and sometimes even attended university, as was the case in an important Hanseatic city such as sixteenth-century Kampen. By contrast, Rotterdam, at that time still a small port town, did not require its secretaries to be university trained. Yet, in both cities, the secretaries kept chronicles.Footnote 54

Whereas we come across several chronicling town secretaries in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, we rarely meet these civil servants in later centuries. Although some chroniclers recorded information that included professional information that might be of use to their successors, there is no evidence that their texts were commissioned or that they were paid for their efforts. From the mid-sixteenth century, we have found only one case of a lay chronicler who was writing at the behest of the institution he was serving. This is Ghent police master Justus Billet (1592–1682) – but, as we will see, he developed the records he was paid to keep in ways that no one had asked him for. That chroniclers were writing at their own initiative is also evident from the fact alone that they often felt free to air a great deal of criticism of local or supralocal authorities. When authors mentioned an intended audience, they often said they were writing for their children or lovers of antiquities, or from other motives such as pleasure or gratitude to God.

Yet even if they were not commissioned to do so, there were many public servants who considered chronicling as an important activity. In our corpus, we came across tax collectors, bookkeepers and clerks, people who were not necessarily highly educated, but who needed to have good writing and arithmetical skills. All these officials had access to professional information that was not always available to the wider public, and often incorporated their knowledge in their chronicles. Some had only a minimal level of schooling. Chronicler Pieter van der Pols from Katendrecht, near Rotterdam, reported that he had become provincial collector of excises in 1750 at the request of the local authorities:

I accepted it; I did not want to decline out of respect. But it’s difficult for someone who is just getting into it, and it’s difficult for me because I am not good at writing and arithmetic. I have only written for 3 to 4 weeks in school, but I enjoyed it, so I practised well in my youth. But I had not thought it would come to a point that I would earn money with it.Footnote 55

Yet there were also chroniclers in this category such as Horatius Vitringa (1631–99) from Leeuwarden, who served as bailiff and as substitute clerk at the Court of Frisia. He had no university training but was nevertheless much more highly educated than someone like Van der Pols: he self-taught his sons, who later attended university.Footnote 56

A second important category of chroniclers were priests, monks, nuns and ministers, 29 in total (together with schoolteachers and professors in category 2 in Table 3). While this group was in general highly literate (female religious were usually less educated), they did not have the same access to local information as those who held public office. The nuns among our authors mostly wrote in the late sixteenth century. After the end of the sixteenth century, most female religious were no longer supposed to leave their convents, and may have depended for information on outsiders. Parish priests and ministers, on the other hand, met people of all ranks, and through their local status, were also trusted with more information.

The third group that stands out are the urban trades and crafts, and to a lesser extent, merchants (category 4 in Table 3). Among the craftsmen in our collection there were many representatives of the more specialized trades, including nine painters, but also a coppersmith, a mirror-maker, a wig-maker and a clock-maker. Nonetheless, this category also includes the more general crafts like a shoe-maker, a tailor and a baker. Some of these authors included a great deal of information about their trade in their texts. Thus, an anonymous chronicle from Antwerp is so full of details about beer and brewers that the author must have been active in the brewing industry.Footnote 57 Joachim Bontius de Waal in Alkmaar wrote in such length and detail about building works in Alkmaar that one suspects he had professional connections with the building trade before he became a ‘rentier’, as the records call him.Footnote 58

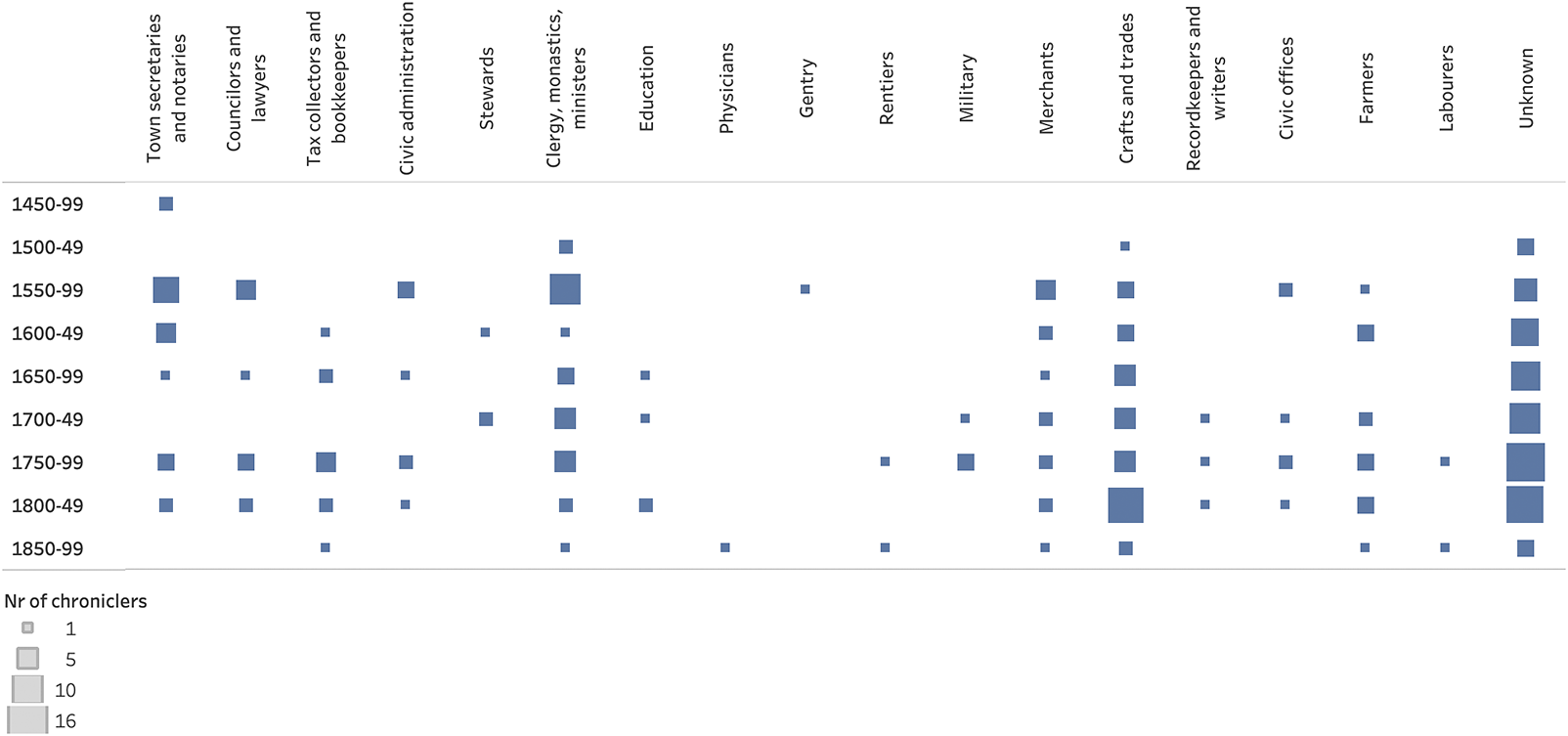

Farmers were also engaged in chronicling, as category 5 of Table 3 shows. Unfortunately, we know little of their social position. We have several authors who were clearly involved in dairy farming, but it is often hard to say anything about the size of their farms, their wealth or their education. Others were farming alongside other activities. This was true for the minister’s wife Aleida Leurink (1682–1755) from the Overijssel village of Losser, and for the Frisian Doeke Hellema (1766–1856), who also worked as a village schoolteacher and as a tax collector. Most of the farmers in our collection were from the North and were Protestants of some persuasion. The number of farmers among our chroniclers increases in the eighteenth and especially the nineteenth centuries. This may indicate that over time chronicling was evolving into a genre for a wider public. As Figure 4 illustrates, such a ‘democratizing’ trend is even more visible in the case of traders and craftsmen, and to a lesser extent, lower government employees (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Occupational categories over time.

All in all, it seems fair to say that from around 1550 chronicling was typically a pastime for public servants, professional people and the upper strata of the self-employed middle classes, people with their own household and their own business.

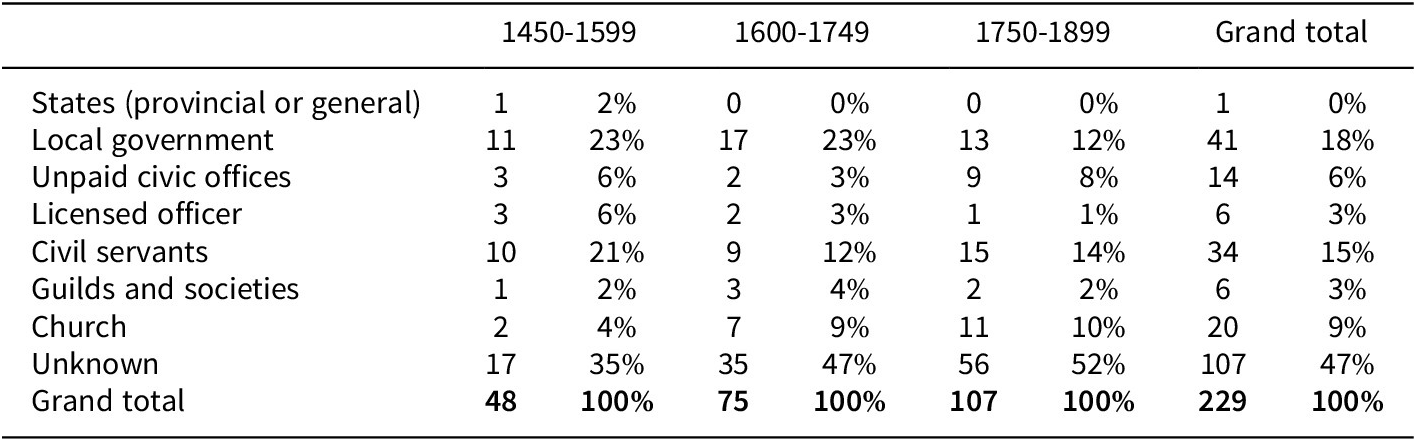

Public roles and authority

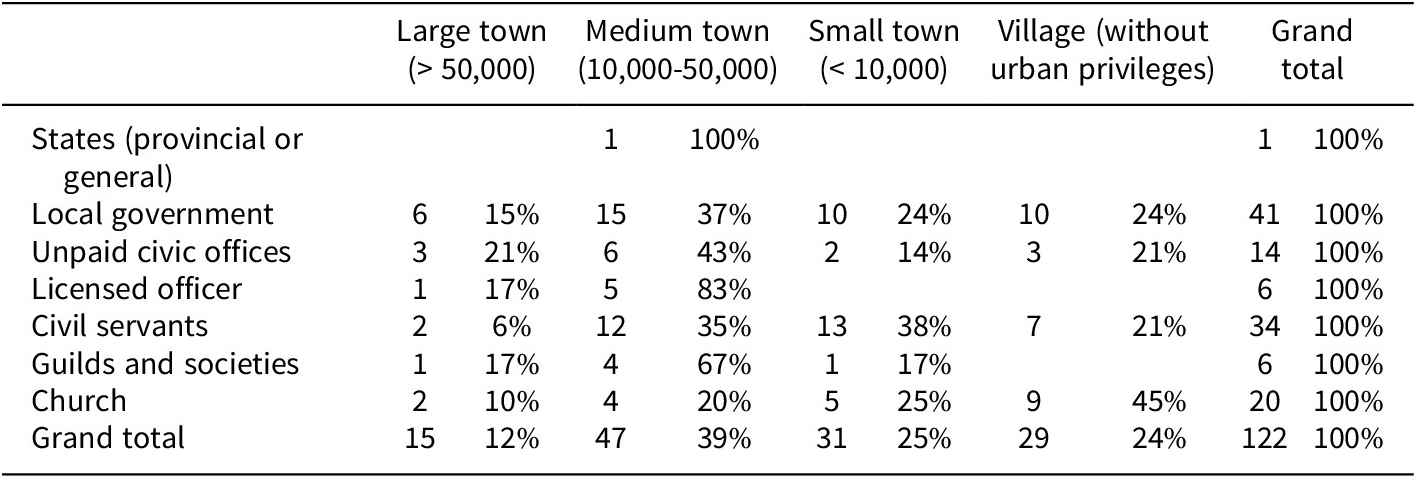

A remarkably high percentage of our chroniclers, whether they were government-employed or not, played some public role in their community, either paid or unpaid.Footnote 59 These roles varied enormously. Some authors held political office, were active in urban corporations or in the church. Others were civil servants or acted in some unpaid civic role. At least 53 per cent of our chroniclers (122 of 229) had such a public role at some point in their life (in Table 4 we counted the highest offices they filled).Footnote 60 It is notable that in large towns relatively few of our authors held high political office, such as burgomaster or schepen (alderman). It is mainly among chroniclers in villages and small towns that we find authors who served as councillor (vroedschap, meente) or schepen, and were thus responsible for governance, justice and a range of other tasks in their communities. Even fewer of these people acquired a political office on a supralocal level such as a provincial or national representative body (see Table 5).

Table 4. Public roles of chroniclers – here the highest office held by each author is counted

Table 5. Public offices held by chroniclers according to town size

Many more either served local government directly, holding one of the many civic offices or having an occupation that was licensed by the local authorities. Besides such civic offices, there were also many other public roles: positions in the urban militia, the governance of charities, leadership roles in guilds and other corporations and associations, as well as work for the church, such as the role of churchwarden, as elder or deacon in the Reformed churches, or as member of a Catholic confraternity. Like political office-holding, these were roles that one owed to one’s honour and standing in the community. While expenses would be covered, and the position might give one access to a profitable social network, there was often no or only a small remuneration for these roles. In towns, they depended in principle on local citizenship, a status that was acquired through birth, marriage or purchase.

Many chroniclers combined public offices or held a number of them in the course of their lifetime. Of known office-holders, 122 held a minimum of 224 offices. The highest number we found was seven in a lifetime. This should not surprise us, because early modern towns depended for their day-to-day running, security and many administrative tasks on the work of their residents. Even in villages, there were dozens of such roles to be filled, so that men of any standing could expect to be called upon to inspect dykes, collect certain moneys or maintain wells.Footnote 61

People who held political office almost invariably began their local careers with other tasks in the community. A typical example is the public career of Marcus van Vaernewyck (1518–69) from Ghent.Footnote 62 In his lifetime, he served as administrator of the poor fund (beheerder van de armenkamer), alderman (schepen van de keure), head of the ‘seven guilds’ (hoofdman van de zeven neringen), churchwarden (kerkmeester) of the St Jacob Church and as factor, or principal poet, of a literary society or rederijkerskamer. Footnote 63 Albert Pieterszoon Louwen (1722–98) from the small town of Purmerend is another case in point.Footnote 64 He was born as the eldest son of a wine merchant. In 1749, aged 37, he became a corporal in the militia, later a sergeant, and thus, as a non-commissioned officer, a member of the military council of Purmerend. He became a churchwarden in 1768, and in 1778 he served as a commissioner for marriage affairs. When his uncle Claes Louwen, council member (vroedschap), passed away in 1779, Albert immediately took his place in the council of the town. In 1788, during the Orange Restoration, the entire council of Purmerend was replaced. The moderately patriotic Louwen claimed he was honourably discharged. During the Batavian Republic in 1795, at the age of 73, he was elected to the new city government and represented Purmerend in the Assembly of Provisional Representatives of the People of Holland, which convened in The Hague from February 1795. As far as we know, this was the highest office he held: whether he was politically or administratively active in the last years of his life is unknown.Footnote 65

Occasionally, public roles overlapped with professional activities. This was particularly true of lower-level public offices, such as town hall clerks, receivers of official dues and excises, city organists and the couples who took care of the day-to-day running of an orphanage, the binnenvader and binnenmoeder. Certain non-administrative offices like postmasterships, peat carrying and operating a ferry service were licensed by the authorities. What distinguished all these positions from a ‘mere’ regular job, is that they not only depended on education and professional expertise, but also had to do with status and standing in the urban community – much like the political officers. The government did not grant these positions to just any resident and required these urban officers to take an oath before the city magistrate and to carry out their services according to various city regulations. It may well be that chroniclers, with their special interest in and knowledge of local history and events, were deemed (at least by themselves) to be particularly well suited for public roles. Yet, conversely, these public roles and the information that came with these positions may also have given these individuals the sense that they were especially well suited to take on a role as chronicler. It is in any case clear that many of them included information that related directly to their public role, and also used the records to which their public position gave them access.

Such access was not self-evident. One reason why some town secretaries wrote chronicles even when they were not commissioned to do so is that they had direct access to the civic records which in early modern societies were not public but part of the arcana imperii. That many chroniclers began their texts by chronicling the histories of their communities – usually by copying information or entire texts from predecessors – and included copies of privileges, charters and so on can thus partly be explained by the fact that access to such information was privileged. To write it down was thus also a way of strengthening the authority of the author.

When it came to their own time many authors also included information that related directly to their public roles. Some chronicles even emerged from such records. The ‘Notebook’ of Pieter Gertses in the Holland village of Jisp began with details about his landownership and the sale of cattle; he only started recording public events when he became schepen and overseer of the orphans.Footnote 66 In nearby Oostzaan, Jan Sijmons Daalder’s chronicle began as a record of marriages, burials and baptisms in the parish church, where he may have served as a sexton, only gradually developing into a record of other events in his community.Footnote 67 Justus Billet’s role as politiemeester in Ghent required him to keep a record of events and changes in the city’s public space, but this developed into a chronicle that covered an enormous range of topics, and also much information about himself.Footnote 68

Yet it could also work the other way round. Authors’ public roles often also explain the inclusion of information that other chroniclers did not consider important enough to record. Leuven chronicler Jan Baptist Hous (1756–1830) had worked as a wig-maker until the French Revolution led to a change in hairstyles – he became a postman and recorded in extraordinary detail what he observed in public space while criss-crossing the city.Footnote 69 Grain inspector Augustijn van Hernighem (c. 1540–1617) recorded an unusual amount of information about events in the countryside around Ypres, which he owed to the farmers whom he met on Saturdays, when they came to town to sell their produce.Footnote 70 Sebastiaan Beringen, keeper of the mills in Roermond, recorded the water levels in the river Roer that affected the running of the mills, while Zacheus de Beer, son of the lock keeper in Spaarndam, also displayed a great deal of interest in water levels.Footnote 71 Luijt Hoogland’s role as foot-bellows operator of the organ in the local church resulted in a great level of detail on events in and around the building, while Doeke Hellema’s role as a founding member of a fire insurance association is evident in a lively interest in fires, as well as extensive reflections on the merits of lightning conductors.Footnote 72

From the surviving introductions, it is also clear that authors aimed to write ‘true’ accounts of what was ‘most memorable’ and ‘most important’, because these would be ‘useful’, not least to themselves. Many chroniclers wrote in times of crisis, with a clear purpose of creating a record of events as they had witnessed them, so that future generations would know the truth, or know of God’s judgments. For many other chroniclers, the aim was simply to collect ‘useful’ information. This information could be historical, because early modern people believed that history was magistra vitae. But Pollmann suggested in 2016 that early modern authors also used their texts to collect useful data that would help establish patterns and correlations. Indeed, quite a few authors used their own records to make comparisons between past and present, or to reflect on changes that they had witnessed. In his dissertation, Dekker shows that they used the information from their chronicles to compare prices, or the severity of cold winters. Baker Jan Gerritsz. Waerschut in Rotterdam used his chronicles to reflect on changes in the built environment of Rotterdam,Footnote 73 while Ypres chronicler Augustijn van Hernighem referred to his own chronicle to look back on the vast political and religious transformations of his time.

As stores of information, chronicles could also help authors to strengthen their authority. In the 1830s, Roermond Sebastiaan Beringen had heard that some people believed that rising population levels would result in food shortages. Yet he dismissed that idea with reference to both Christ’s miraculous multiplication of bread and fish at the Sea of Galilee, and his own records of local grain prices, which had not risen.Footnote 74 They were not always successful in persuading others. Lambert Lustigh (1656–1727) from the village of Huizen tried to use his records of sickness and deaths among local cows to persuade his neighbours of his theory on how the rinderpest epidemic should be tackled.Footnote 75 That he did not succeed may have had something to do with his membership of a conventicle which was not approved of by the local Reformed church. Yet what any chronicler hoped for, and which was an important reason to write in times of crisis, was to keep memories alive for future generations. In Leuven, Jan-Baptiste Hous used his chronicle to carefully document the lack of support for the new regime, while Van der Straelen in Antwerp used it to record French depredations.Footnote 76

Conclusion

What can we deduce from these data? First, it is interesting to note that while an ever-widening group of people took it upon themselves to start a chronicle, we do not see a loss of interest in chronicling among the highly educated people in the bigger cities, or people in the upper middle classes, in either the Northern or Southern Netherlands. That women and more villagers became active as chroniclers as our period progressed was probably due to a variety of factors – paper became much cheaper, the number and circulation of printed texts increased and writing skills may have improved.Footnote 77 We do not believe it points to a change in the cultural status or prestige of chronicling as an activity per se. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, ‘enlightened’ people of considerable intellectual ambition remained keen to collect, cite and continue the texts of their predecessors, and chroniclers clearly did keep abreast of intellectual changes. If anything, we see a rise in the intellectual ambitions and scope of chroniclers – the studies of Lassche and Dekker show that there was more explicit engagement with a range of printed historical texts, for instance, and a greater use of numerical data derived from newspapers, as well as information gained from conversations, letters and public proclamations.Footnote 78

Secondly, while the occupational profile of our chroniclers was not so different from what we expected, we were intrigued by their intensive involvement in paid or unpaid public roles of one sort or another. While it is well known that a large percentage of male burghers did at some point or another undertake such roles in Low Countries’ communities, it is nevertheless significant to find that chronicling was for a large part the activity of people who had a public role. In some cases, this affected their access to non-public information – as chroniclers obtained new offices, they also recorded new types of data. Thus, Rotterdam chronicler Jacob Lois only began to record supralocal news when he became schepen in his hometown.Footnote 79 The sense of responsibility for the recording of local affairs and the associated authority of their claims, which Pollmann earlier hypothesized derived from the authors’ ability to write longer texts, may thus be better explained with reference to the sense of civic responsibility and authority that derived from involvement in public affairs – even at the level of working as a sexton or an organist.

Implicitly or explicitly, chroniclers claimed authority by the act of chronicling. They took charge of selecting what they deemed to be important, memorable, useful and true knowledge. Their public roles offered them some civic standing, and often gave them access to information that was not so easily obtained by others. Yet this also worked the other way round. By keeping a chronicle, authors put together a store of knowledge that enhanced their status and could be used to strengthen their claims to a public role. It is notable that in that process they rarely sought to foreground themselves as individuals. This is not because they did not have a ‘sense of self’, as has sometimes been suggested. Rather, this is a function of the genre.Footnote 80 It was to enhance the authority of their texts that chroniclers chose to present themselves as neutral and impartial observers, and often also as part of a chain of predecessors on whose knowledge and reputation they built, and with whom they shaped the history and reputation of their ‘beloved’ town or village.

For that reason, we also believe that chronicles help us better establish how local identities were experienced. It is well known how much energy the governing authorities of early modern European towns expended on fostering their own reputation, memorializing their past, and branding their cities. It has been harder to assess how seriously local people took such efforts and in what ways they shared in local pride. Here, chronicles can help – they show us clearly in what way authors were the stakeholders in their local community.Footnote 81

Funding statement

The research for this article was funded by a grant from the Dutch Research Council NWO; the publication of the data collection was also supported by grants from the Leiden University Fund LUF, the Gratama Foundation and CLUE+ at VU University.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.