Introduction

The last few decades have featured remarkable shifts in attitudes towards gender and sexuality, with increasing recognition and acceptance of people who identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer (LGBTQ+) (Perales and Campbell Reference Perales and Campbell2018; Roberts Reference Roberts2019). Despite these positive developments, LGBTQ+ people continue to face disadvantage in multiple facets of social life (Charlton et al Reference Charlton, Gordon, Reisner, Sarda, Samnaliev and Austin2018). Within the labour market, research has shown that LGBTQ+ people generally experience substantially poorer outcomes than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts. This situation applies both to objective outcomes – e.g., labour-force participation and unemployment (Laurent and Mihoubi Reference Laurent and Mihoubi2017; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk, Tatli, Broadbridge and Fielden2018), earnings (LaNauze Reference La Nauze2015; Waite and Denier Reference Waite and Denier2015), and career progression (Gedro Reference Gedro2010; Köllen Reference Köllen2018; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk, Tatli, Broadbridge and Fielden2018) – and subjective outcomes – e.g. job satisfaction (Leppel Reference Leppel2014) and workplace well-being (Donaghy and Perales Reference Donaghy and Perales2024). It also extends to multidimensional measures of job quality and precarious employment encompassing both subjective and objective components (see e.g., Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023). Notwithstanding this increasing understanding, the evidence base remains far from comprehensive. In particular, empirical studies have largely overlooked how employment arrangements vary by workers’ LGBTQ+ status (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024; Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023; Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi, Kia, MacKinnon, MacEachen, Gesink and Ross2024a). As a result, we know little about LGBTQ+ individuals’ relative propensity to be in temporary, irregular, or contingent forms of employment. This is an important omission, as the nature of the employment relationship is a central feature of work and can either enhance or diminish workers’ physical and mental well-being (Eurofound 2018; Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b; Robone et al Reference Robone, Jones and Rice2011).

To address this knowledge gap, the present study examines the comparative employment arrangements of LGBTQ+ people, with a particular focus on non-standard employment (NSE). We refer to NSE as an umbrella term encompassing employment forms that deviate from the ‘standard’ employment relationship between an employer and an employee which is characterised by permanent, full-time employment (ILO 2016). As such, NSE may include self-employment, part-time employment, fixed-term employment, and/or casual work (ILO 2016; Lass and Wooden Reference Lass and Wooden2020). In Australia – where the current study is based – NSE accounts for approximately half of total employment (Lass and Wooden Reference Lass and Wooden2020), further underscoring the importance of this line of inquiry. The growth of NSE both in Australia and internationally has sparked concerns arising from NSE’s broad relationships with precarity and poor job quality (Campbell and Price Reference Campbell and Price2016; Kalleberg et al Reference Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson2000; McGovern et al Reference McGovern, Smeaton and Hill2004). Existing studies have shown that NSE is generally associated with a host of negative objective and subjective labour-market outcomes, including a lack of job security and employment benefits (ILO 2016; Kalleberg et al Reference Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson2000; Quinlan Reference Quinlan2015), wage penalties (Lass and Wooden Reference Lass and Wooden2020; Quinlan Reference Quinlan2015), and lower job satisfaction and worker well-being (Buddelmeyer et al Reference Buddelmeyer, McVicar and Wooden2015; D’Addio et al Reference D’Addio, Eriksson and Frijters2007; Green and Heywood Reference Green and Heywood2011). While not all NSE is precarious and some NSE may offer certain perks (ILO 2016), as we later argue, the downsides of non-standard employment arrangements may be felt particularly strongly by some population groups – including LGBTQ+ workers.

Against this backdrop, the current study theorises and provides novel evidence on the relationships between LGBTQ+ status, NSE, and workplace well-being. First, it considers whether LGBTQ+ employees are more likely than their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts to be in different types of NSE. Second, it examines whether NSE is more detrimental to LGBTQ+ compared to non-LGBTQ+ employees. In doing so, we focus on employees’ workplace well-being: a multidimensional concept encapsulating constructs such as productivity, attachment, engagement, and psychological well-being (Lyubomirsky Reference Lyubomirsky2001; Page and Vella-Brodrick Reference Page and Vella-Brodrick2009; Wijngaards et al Reference Wijngaards, King, Burger and van Exel2022). To accomplish the study aims, our empirical analyses leverage data from a recent and unique employer-employee survey capturing the workplace experiences of LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ employees in Australia. Our results reveal the existence of a ‘double whammy’ for LGBTQ+ people in relation to NSE: LGBTQ+ employees are both comparatively more likely to be in problematic forms of NSE and also more negatively impacted by these employment arrangements.

Literature review

LGBTQ+ people and the labour market

While a workplace can serve as a place of community and support, they are also characterised by social and cultural norms regarding identity, relationships, and performance (Donaghy and Perales Reference Donaghy and Perales2024; Ozturk et al Reference Ozturk, Rumens and Tatli2024). Collectively, these norms give rise to different organisational climates or cultures (Owens et al Reference Owens, Mills, Lewis and Guta2022). In relation to sex and sexuality, research documents how heterosexism and cisnormativity remain pervasive features of modern organisations (Ozturk Reference Ozturk, Forson, Healy, Öztürk and Tatli2024; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk and Tatli2016; Rumens Reference Rumens, Broadbridge and Fielden2018). This set of norms privileges heterosexual different-gender relationships and enforces conformity to traditional gender identity binaries (Perales et al Reference Perales, Campbell and Elkin2024a). As Ozturk (Reference Ozturk, Forson, Healy, Öztürk and Tatli2024) explains, core workplace normativities include heteronormativity, homonormativity, cisnormativity, and transnormativity. These forces act in tandem to subject employees from sexual and gender minorities to normalising pressures, with any transgressions yielding significant penalties – including organisational marginalisation and exclusion (Ozturk Reference Ozturk, Forson, Healy, Öztürk and Tatli2024). Due to both being pressured to conform to these normative expectations and as a form of policing or punishment for any deviations, LGBTQ+ employees become exposed to a range of unique workplace stressors (Meyer Reference Meyer2003). While most organisational research in this space has focused on employees’ sexuality diversity, an analogous and rapidly emerging field has considered employees’ gender diversity – including research on the unique challenges faced by binary and non-binary trans employees (see e.g. Köllen Reference Köllen2018; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk and Tatli2016; Ozturk et al Reference Ozturk, Rumens and Tatli2024).

As posited by minority-stress theoretical perspectives (Cancela et al Reference Cancela, Stutterheim and Uitdewilligen2024; Meyer Reference Meyer2003; Velez et al Reference Velez, Moradi and Brewster2013), stressors can be categorised as distal or proximal. Distal minority stressors encompass external, interpersonal forms of discrimination, stigma, and harassment against LGBTQ+ employees (Cancela et al Reference Cancela, Stutterheim and Uitdewilligen2024; Meyer Reference Meyer2003; Velez et al Reference Velez, Moradi and Brewster2013). In contrast, proximal minority stressors involve intra-individual psychological processes occurring within LGBTQ+ employees as a result of distal stressors. Expectations of rejection, fear of harm, internalisation of stigma, and identity concealment are examples of proximal stressors affecting LGBTQ+ employees (Cancela et al Reference Cancela, Stutterheim and Uitdewilligen2024; Meyer Reference Meyer2003; Velez et al Reference Velez, Moradi and Brewster2013). Empirical research has found consistent evidence of LGBTQ+ employees being impacted by both types of stressors at work (Maji et al Reference Maji, Yadav and Gupta2024). In turn, these stressors have negative repercussions on LGBTQ+ people’s labour-market outcomes. As noted earlier, this situation contributes to disparities in wages, career progression, job satisfaction, job quality, and workplace well-being, amongst others (see e.g. Drydakis Reference Drydakis2022a; Gedro Reference Gedro2010; Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023; La Nauze Reference La Nauze2015; Lacatena et al Reference Lacatena, Ramaglia, Vallone, Zurlo and Sommantico2024; Leppel Reference Leppel2014; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk, Tatli, Broadbridge and Fielden2018; Waite and Denier Reference Waite and Denier2015).

Non-standard employment amongst LGBTQ+ employees: existing evidence

While a mature body of work demonstrates that LGBTQ+ populations have poorer work outcomes, existing scholarship has paid little attention to their employment arrangements (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024; Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi, Kia, MacKinnon, MacEachen, Gesink and Ross2024a), despite these constituting a core work feature with extensive links to well-being (Eurofound 2018; Robone et al Reference Robone, Jones and Rice2011). Indeed, to our knowledge, only one previous study has compared rates of NSE between LGBTQ+ and other workers. Using the 2016 Canadian General Social Survey and cross-sectional regression models, Kinitz et al (Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023) found that lesbian, gay, and bisexual workers were significantly more likely to be employed on precarious working arrangements, including part-time, temporary, and irregular employment. As explained below, the present study adds to these pioneer findings in several ways. Chiefly, it examines potential disparities by LGBTQ+ status in the impacts of NSE on workplace well-being and whether previous findings hold in a new country context (Australia).

Non-standard employment and workplace well-being

As we explained before, NSE has been linked to a range of undesirable outcomes, including employment insecurity, lack of employment protection and benefits, and lower wages (ILO 2016; Quinlan Reference Quinlan2015; Schmid and Wagner Reference Schmid and Wagner2017). These factors can in turn deplete workers’ workplace well-being by increasing feelings of uncertainty and powerlessness, as well as exposure to physically and psychosocially harmful working conditions or material deprivation (Julia et al Reference Julià, Vanroelen, Bosmans, Van Aerden and Benach2017). Precarious employment – including NSE – may also negatively affect workers’ mental health through the ascription of the marginalised identity/status of ‘precarious worker’ (Irvine and Rose Reference Irvine and Rose2024). It is nevertheless important to note that, as some scholars have argued, not all NSE is problematic (Vives et al Reference Vives, Gonzalez Lopez and Benach2020). Indeed, certain forms of NSE may offer benefits that could increase workers’ well-being, such as greater flexibility, task variety, and work-life balance (ILO 2016; Julia et al Reference Julià, Vanroelen, Bosmans, Van Aerden and Benach2017). These benefits may be valuable to particular subgroups, such as people who need to balance paid and unpaid care work (Booth and van Ours Reference Booth and van Ours2009).

Several empirical studies have examined associations between NSE and workplace well-being through proxy measures such as job satisfaction (see e.g., Bardasi and Francesconi Reference Bardasi and Francesconi2004; Buddelmeyer et al Reference Buddelmeyer, McVicar and Wooden2015; D’Addio et al Reference D’Addio, Eriksson and Frijters2007; Wilkin Reference Wilkin2013). Overall, these studies observe slightly lower levels of job satisfaction amongst non-standard workers relative to permanent full-time workers. These findings thus reinforce NSE’s theoretical status as a generally disadvantageous employment arrangement. Nonetheless, there is also substantial heterogeneity amongst NSE workers, with fixed-term workers reporting similar job satisfaction as full-time permanent workers, and casual, seasonal, and temporary workers reporting distinctly lower satisfaction (Bardasi and Francesconi Reference Bardasi and Francesconi2004; D’Addio et al Reference D’Addio, Eriksson and Frijters2007; Green and Heywood Reference Green and Heywood2011). Evidence of the association between part-time work and job satisfaction is less conclusive, with studies finding mixed effects often structured along gender lines (Booth and van Ours Reference Booth and van Ours2009; Montero and Rau Reference Montero and Rau2015). Previous research focusing exclusively on LGBTQ+ people has also documented lower well-being amongst those in NSE compared to those with standard employment arrangements (Owens et al Reference Owens, Mills, Lewis and Guta2022). Whether non-standard employment differentially affects the workplace well-being of LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ employees, however, remains an open question.

Theorising the relationships between LGBTQ+ status, non-standard employment, and workplace well-being

In this section, we elaborate on different ways in which NSE, workplace well-being and LGBTQ+ status may be theoretically connected. Following Staub (Reference Staub2014, 371), the relationship between NSE and workplace well-being can be decomposed into an extensive margin, or the ‘part attributable to individuals starting to participate’ and an intensive margin, or the ‘part attributable to already participating individuals’. Here, the extensive margin pertains to LGBTQ+ employees’ likelihood of being in NSE relative to non-LGBTQ+ employees, while the intensive margin refers to the potential differential effect of NSE on the workplace well-being of LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ employees.

The extensive margin: LGBTQ+ employees’ overrepresentation in NSE

As some scholars have noted, NSE is more common amongst comparatively disadvantaged population groups – such as women, ethnic minorities, and younger or older individuals (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024; Kalleberg and Vallas Reference Kalleberg and Vallas2017). While evidence pertaining to LGBTQ+ status is incipient, the literature offers multiple theoretical reasons why LGBTQ+ employees may also be overrepresented in NSE. Taste-based theories of discrimination (Becker Reference Becker1957; Drydakis Reference Drydakis2022b) can be combined with the notion of distal minority stressors (Meyer Reference Meyer2003) to offer one prediction. Within this framework, employers may actively discriminate against LGBTQ+ individuals because of their stigmatised social status. Through management or HR practices, employers can enact their discriminatory preferences by denying new LGBTQ+ hires more desirable permanent full-time employment positions, or by tracking their existing LGBTQ+ employees into NSE arrangements or career pathways. Consistent with this proposition, audit studies have found that individuals identifying as LGBTQ+ are less likely to receive callbacks from potential employers (Mishel Reference Mishel2016; Tilcsik Reference Tilcsik2011). We argue that this sort of discrimination can also extend to other work domains, including the employment relationship.

In addition, proximal minority stressors may also influence LGBTQ+ people’s job-seeking practices. For instance, if LGBTQ+ individuals are more likely to feel worthless or valueless (proximal stressors) due to their exposure to stigma and discrimination, they may also be less likely to aspire to, seek, and apply for more highly esteemed permanent full-time positions. Likewise, LGBTQ+ employees may sort themselves or self-select into NSE as an identity-management strategy (Ragins Reference Ragins2008). Concealment of LGBTQ+ status may be easier when the work is temporary or contingent – as in the case for NSE – as it may allow LGBTQ+ employees to maintain social distance and avoid discussions about their personal life, including their sexual and/or gender identities (Ragins Reference Ragins2008). This is consistent with Holmes et al’s (Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024) observation that LGBTQ+ workers may forgo opportunities for career progression if the new role requires one’s partner to become more visible.

Additionally, evidence suggests that LGBTQ+ employees may self-select into certain industries or occupations where NSE is more prevalent. For example, LGBTQ+ workers are overrepresented in the arts and creative industries, as these may provide ‘safe havens’ for minority groups (Tilcsik et al Reference Tilcsik, Anteby and Knight2015; Zindel and de Vries Reference Zindel and de Vries2024). However, jobs in these sectors are also more precarious in nature, due to their reliance on project-specific arrangements (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024). The occupational segregation of LGBTQ+ workers may also stem from other factors. For instance, Tilcsik et al (Reference Tilcsik, Anteby and Knight2015) found that LGBTQ+ workers choose occupations that require greater task independence and/or social perceptiveness. Some of these occupations may also be characterised by a preponderance of NSE arrangements. Altogether, these factors align with the concept of a ‘lavender ceiling’ for LGBTQ+ workers (Gedro Reference Gedro2010; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk, Tatli, Broadbridge and Fielden2018). While the concept has usually been applied in the context of career progression, here we argue that it also extends to LGBTQ+ workers’ employment arrangements.

These diverse mechanisms were elegantly tied together in a recent study using in-depth qualitative interviews by Kinitz et al (Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b). Their findings unveiled an overarching narrative characterising LGBTQ+ people’s pathways to NSE, one that extends from their early life experiences to their labour-market entry and workplace experiences. Key factors pushing LGBTQ+ individuals into NSE and other forms of precarious employment included stigma and discrimination limiting their ability to complete their education and plan their careers, limited opportunities to fulfil cis and heteronormative labour-market ideals, and a lack of employer protections against workplace stressors and victimisation (Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b).

Based on the theoretical propositions discussed within this section, and the initial findings for Canada reported by Kinitz et al (Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023, Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b), we expect that in our Australian sample LGBTQ+ employees will be more likely than non-LGBTQ+ employees to be in NSE (Hypothesis 1).

The intensive margin: Excess negative effects of NSE on LGBTQ+ employees’ well-being

In addition to being overrepresented in NSE, LGBTQ+ workers may also be differentially impacted by these employment arrangements. A recent study from Canada showed that the inverse relationship between NSE and well-being reported in the broader literature was also apparent within a sample of LGBTQ+ respondents (Owens et al Reference Owens, Mills, Lewis and Guta2022). However, to our knowledge, no previous research has examined whether NSE exerts a differential effect on the well-being of LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ employees. Despite this, different theoretical perspectives lend support to the expectation that NSE may exert more detrimental effects on the well-being of LGBTQ+ workers compared to non-LGBTQ+ workers.

As previously argued, for most individuals, NSE represents a riskier and less desirable outcome than permanent full-time employment. This is because NSE is often – though not always – characterised by disadvantageous features, including precariousness, insecurity, underinsurance, or limited employer benefits (ILO 2016; Kalleberg et al Reference Kalleberg, Reskin and Hudson2000; Quinlan Reference Quinlan2015). These features can in turn result in negative feelings (e.g., uncertainty, powerlessness and dissatisfaction) and poorer financial and career outcomes amongst NSE workers and thus represent general stressors that apply to both LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ employees. However, as explained before, LGBTQ+ individuals are also exposed to additional unique minority stressors due to their stigmatised identities (Meyer Reference Meyer2003). Based on the stress process model, the degree to which stressors negatively impact individuals’ well-being depends on the amount of stress already accumulated by the individual (Pearlin et al Reference Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman and Mullan1981). This perspective further posits that additional stressors compound to multiplicatively (rather than additively) deplete well-being (Pearlin et al Reference Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman and Mullan1981). Therefore, for LGBTQ+ individuals, the stressors stemming from NSE will compound with those stemming from holding a stigmatised identity – exerting a multiplicative negative effect on their workplace well-being. Of note, this idea is similar to those underpinning cumulative-disadvantage perspectives, which posit that multiple disadvantages can compound and exacerbate each other’s negative effects on life outcomes (DiPrete and Eirich Reference DiPrete and Eirich2006; Merton Reference Merton1988).

In addition, other reasons lead us to expect the features of NSE to pose greater challenges for LGBTQ+ than non-LGBTQ+ employees. For example, the temporary and/or contingent nature of NSEs may limit LGBTQ+ employees’ voices at work, making them feel less empowered to speak up about negative incidents for fear of losing their job (Owens et al Reference Owens, Mills, Lewis and Guta2022). Additionally, the lack of employment benefits associated with NSE – such as health insurance and paid leave – may be particularly detrimental to the well-being of LGBTQ+ employees. As Owens et al (Reference Owens, Mills, Lewis and Guta2022) argue, the ability to access mental-health supports or take special leave can mitigate the unique stressors experienced by some LGBTQ+ employees (e.g., transgender employees). Finally, the lower levels of social support experienced by LGBTQ+ people mean that these individuals have fewer buffers to cushion against employment-related risks and challenges. For instance, many LGBTQ+ people are estranged from their families of origin (Reczek and Bosley Smith Reference Reczek and Bosley-Smith2021), who often serve as a safety net in the event of personal stress, job loss or financial difficulties (Swartz et al Reference Swartz, Kim, Uno, Mortimer and O’Brien2011).

In a recent study based on biographical interviews, Kinitz et al (Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen and Gesink2024c) provide further in-depth insights into how LGBTQ+ status becomes progressively intertwined with NSE and mental-health outcomes. The authors document a cyclical pattern that unfolds over time, whereby LGBTQ+ individuals’ mental health initially depletes following from – often involuntary or pressured – labour-market exits. From then on, precarity (including periods of NSE) characterised participants’ attempts to regain paid employment, with these suboptimal working arrangements yielding further negative impacts on their mental well-being (Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen and Gesink2024c).

Altogether, based on the theoretical tenets discussed within this section, we expect that NSE will exert a more deleterious effect on the workplace wellbeing of LGBTQ+ compared to non-LGBTQ+ employees (Hypothesis 2).

Data and methods

The 2024 Australian Workplace Equality Index Employee Survey

To test the hypotheses outlined in the previous section, we leverage data from the 2024 Australian Workplace Equality Index (AWEI) Employee Survey, an annual employer-employee dataset collecting information on the workplace experiences of LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ employees. Participating organisations are either members of ACON Health’s Pride Inclusions Programs, or organisations that choose to participate, with all employees within these organisations being encouraged to complete an online survey instrument. The 2024 AWEI Survey encompasses responses from 42,219 individuals working for 174 employers across Australia. This includes detailed information on core aspects for this study, namely LGBTQ+ status, workplace well-being, and non-standard employment. Critically, and given its focus on diversity and inclusion, the survey features a large number of LGBTQ+ respondents (n = 10,396), which enables us to bypass small-sample issues faced by earlier studies.

Key analytic variables

Non-standard employment

Using the information available in the 2024 AWEI Employee Survey, we derive a measure of NSE using responses to the following question: ‘What is your employment type?’. Respondents who were in permanent full-time employment were identified through the response option ‘Full-time (paid staff)’ and represent 84.6% of the sample (see Appendix Table A1). Respondents in different forms of NSE were identified through the response options ‘Part-time (paid staff)’ (9.2% of the sample), ‘Contract (fixed-term paid staff)’ (3.9%), ‘Temporary/Casual (paid staff)’ (1.9%), ‘Volunteer/Non-paid staff member (inc. student placement)’ (<1%), and ‘Another employment type’ (<1%).Footnote 1 Due to small numbers, some of these categories are combined in subsequent analyses. In addition, we also explore a dichotomous measure of NSE, where permanent full-time employment takes the value zero and all forms of NSE take the value one.

Respondents’ LGBTQ+ status is derived by combining information on respondents’ self-reported sex assigned at birth, gender identity and sexual orientation. Respondents are considered to belong to the LGBTQ+ group if their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth and/or their sexual identity deviates from heterosexuality. This includes respondents who reported: (a) any sexual orientation other than ‘heterosexual’ (i.e., ‘Gay, Lesbian (Homosexual)’, ‘Bisexual’, ‘Queer’, ‘Pansexual’, ‘Asexual’ and ‘A different term’); (b) a non-binary or ‘other’ gender identity; and/or (c) having a sex assigned at birth of male (female) and a gender of female (male) (i.e., binary trans participants). Approximately 26.2% of the sample fell into the LGBTQ+ group using this operationalisation (Table A1). Of the remaining respondents, 72.9% were non-LGBTQ+ and 2.5% did not provide sufficient information to be allocated to the LGBTQ+ or non-LGBTQ+ category.

Workplace well-being

Following earlier studies (Donaghy and Perales Reference Donaghy and Perales2024; Perales Reference Perales2022; Perales et al Reference Perales, Campbell and Elkin2024b), we derive a composite index of workplace well-being by combining information on different dimensions of this concept recognised in the literature (see e.g., Lyubomirsky Reference Lyubomirsky2001; Page and Vella-Brodrick Reference Page and Vella-Brodrick2009; Wijngaards et al Reference Wijngaards, King, Burger and van Exel2022). Specifically, we leverage information from a dedicated six-item question battery included within the 2024 AWEI Employee Survey, where respondents rated their agreement on a Likert scale (1 = ‘Strongly disagree’; 5 = Strongly agree’). The statements are as follows: (i) ‘I feel safe and included within my immediate team’, (ii) ‘I feel mentally well at work’, (iii) ‘I feel I can be myself at work’, (iv) ‘I feel productive at work’, (v) ‘I feel engaged with the organisation and my work’, and (vi) ‘I feel a sense of belonging here’.

All item scores were first averaged and then added up into a composite index. To ease interpretability, index scores were subsequently transformed to range from 0 (lowest well-being) to 100 (highest well-being) using the following linear transformation: index score = (average item score – 1) × 20. The resulting index exhibited optimal statistical properties, with Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.94 and optimal item-rest correlations ranging from 0.75 to 0.87. Additionally, principal component analyses provided strong evidence of unidimensionality, with just one factor with an Eigenvalue over one (Eigenvalue = 4.28) explaining 76% of the variance. The average level of workplace well-being in the sample was 78.3 (out of 100) and the standard deviation was 20.6.Footnote 2

Estimation

In the first set of analyses, we fit a multinomial logistic regression model to examine the association between LGBTQ+ status (explanatory variable) and type of NSE (outcome variable). This model aims at establishing whether or not LGBTQ+ workers are overrepresented in different forms of NSE, relative to non-LGBTQ+ workers (Hypothesis 1). We present results of both an unadjusted model and a model adjusted for a set of individual-level factors that may otherwise act as confounders. The latter includes respondents’ sex, residence in a rural area, age group, Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) status, Indigenous status, disability status, and religious identification. Descriptive statistics on these control variables are presented in Table A1. To account for the repeated observations from individuals working in the same employer, the model’s standard errors are clustered across organisations. The reference category for the multinomial outcome variable in these models is ‘permanent full-time employment’.

In a second set of analyses, we fit a series of linear random-effect regression models examining the associations between LGBTQ+ status, NSE, and their interaction (explanatory variables) on workplace well-being (outcome variable).Footnote 3 These models aim to test our second hypothesis by establishing whether any negative impact of NSE on workplace well-being is larger amongst LGBTQ+ workers. In these models, the nesting of workers within organisations is accounted for through an organisation-level random intercept (or random effect).Footnote 4 To account for possible confounding, the models are adjusted for relevant individual- and organisational-level factors including respondents’ sex, age group, CALD, Indigenous and disability statuses, religious identification, rural area residence, and job tenure and level, as well as employers’ sector and industry (see Table A1 for descriptive statistics). For explanatory purposes, we fit these models with and without controls and with and without a LGBTQ+ × NSE interaction term (the latter representing the key parameter to test Hypothesis 2).

Results

Bivariate associations

Table A1 shows sample descriptive statistics, overall and stratified by LGBTQ+ status. The figures indicate that LGBTQ+ respondents are more likely than non-LGBTQ+ respondents to be in certain types of NSE, including contract/fixed-term work (4.7% compared to 3.6%) and temporary/casual work (2.9% compared to 1.6%), but less likely to be in part-time employment (7.3% compared to 9.8%). Results from a Chi2 test reveal that this bivariate association is statistically significant (Chi2 = 154.3; p < 0.01). The raw data also show that workplace well-being is lower amongst LGBTQ+ workers (mean = 76.2) than non-LGBTQ+ workers (mean = 79.4). Results from an ANOVA test comparing all three categories of the LGBTQ+ variable (F = 154.3; p < 0.01) and a t-test comparing the LGBTQ+ and non-LGBTQ+ groups (t = 13.2; p < 0.01) reveal that these bivariate associations are statistically significant. Altogether, these descriptive statistics suggest systematic differences in employment type and workplace well-being by LGBTQ+ status. Confirming the robustness of these relationships and establishing more nuanced patterns of association requires multivariable modelling, to which we turn in the next section.

Models of non-standard employment

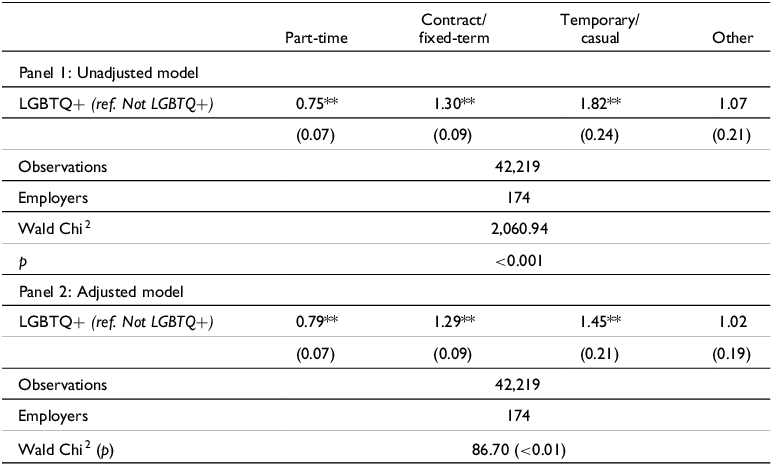

To test Hypothesis 1, we fit multinomial logistic regression models of NSE. Abridged results are presented in Table 1 (see Appendix Table A2 for full sets of model parameters). The results are expressed as relative risk ratios (RRRs), which give the odds of respondents being in a given category of the outcome variable (relative to the reference category of full-time employment) associated with a one-unit increase in the explanatory variables. The RRRs in both the adjusted and unadjusted models indicate that LGBTQ+ individuals are overrepresented in some forms of NSE, including contract/fixed-term work (RRRadjusted = 1.30; p < 0.01 & RRRunadjusted = 1.29; p < 0.01) and temporary-casual work (RRRadjusted = 1.82; p < 0.01 & RRRunadjusted = 1.45; p < 0.01). However, LGBTQ+ individuals are comparatively less likely to be in permanent part-time employment than non-LGBTQ+ individuals (RRRadjusted = 0.75; p < 0.01 & RRRunadjusted = 0.79; p < 0.01).Footnote 5

Table 1. Relative risk ratios and standard errors from multinomial logistic regression models of non-standard employment (reference: full-time employment)

Notes. 2024 AWEI Employee Survey. Standard errors in parentheses. LGBTQ+: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer. Controls include respondents’ sex recorded at birth, residence in a rural area, age group, culturally and linguistically diverse status, Indigenous status, disability status, and religious identification. Standard errors clustered on organisations. Statistical significance: # p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, our results thus indicate that LGBTQ+ status is associated with overrepresentation in some forms of NSE (contract/fixed-term and temporary/casual work) – although they also point to an underrepresentation of LGBTQ+ workers in part-time employment. The additional random-effect logistic regression models in Appendix Table A4 explore whether LGBTQ+ individuals are underrepresented in NSE overall (i.e., using a binary measure of ‘any NSE’ as the outcome). The associated odds ratios (ORs) indicate that this is the case for the unadjusted model (OR = 0.93; p < 0.05), but not for the adjusted model (OR = 0.96; p > 0.1).

Since LGBTQ+ status is further ‘upstream’ in the causal pathway to NSE than employer characteristics, the control variables in the models discussed so far exclude organisation-level controls. Adding a selection of employer characteristics to this model, however, can help elucidate the reasons why LGBTQ+ individuals may be overrepresented in certain types of NSE. In this vein, the multinomial logit model shown in Appendix Table A5 presents results further adjusted by employer sector and industry. With the addition of these controls, the RRRs on LGBTQ+ status for contract/fixed-term and temporary/casual work fall closer to the neutral point of one. This pattern of results suggests that sector and industry sorting is only responsible for a modest amount of the overrepresentation of LGBTQ+ individuals in those types of NSE.

Models of workplace well-being

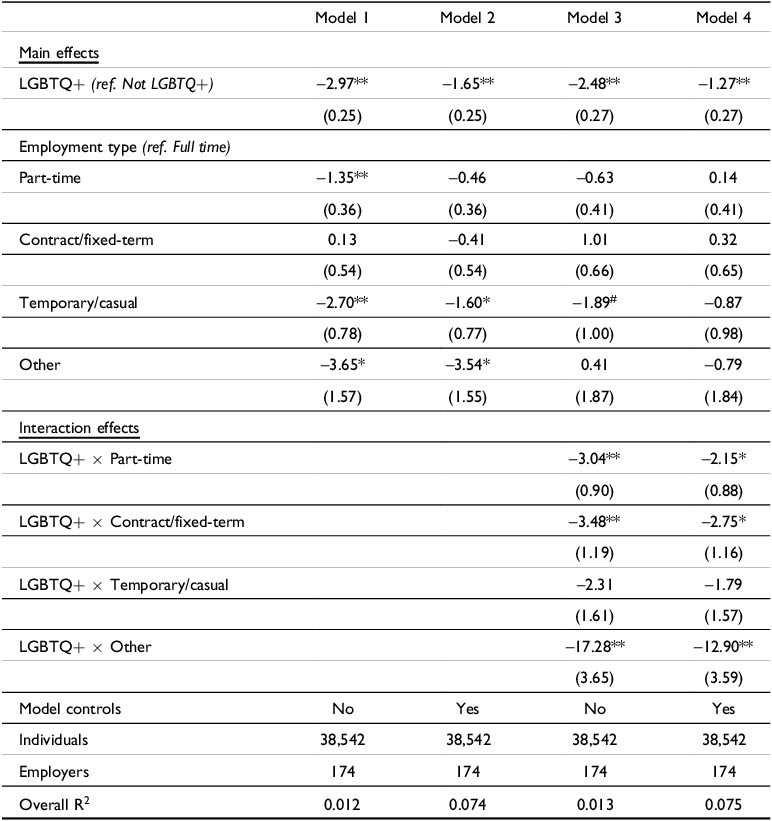

To test Hypothesis 2, we fit a series of linear random-effect regression models of workplace well-being, with and without model controls and with and without ‘LGBTQ+ × NSE’ interactions. The model coefficients presented in Table 2 give the change in workplace well-being associated with a one-unit increase in the focal explanatory variables (a full set of model estimates is available in Appendix Table A3). Aligning with the extant literature, the results of Models 1 and 2 confirm that LGBTQ+ status is associated with lower workplace well-being (βadjusted = –2.97; p < 0.01 & βunadjusted = –1.65; p < 0.01). The same applies to certain types of NSE. Relative to individuals in permanent full-time employment, workplace well-being is lower for those in permanent part-time work (βunadjusted = –1.35; p < 0.01), temporary/casual work (βadjusted = –2.70; p < 0.01 & βunadjusted = –1.60; p < 0.05), and other NSE work (βadjusted = –3.65; p < 0.05 & βunadjusted = –3.54; p < 0.05).

Table 2. Coefficients and standard errors from linear random-effect regression models of workplace well-being

Notes. 2024 AWEI Employee Survey. Standard errors in parentheses. LGBTQ+: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer. Controls include respondents’ sex recorded at birth, residence in a rural area, age group, culturally and linguistically diverse status, Indigenous status, disability status, religious identification, job tenure, and job level, and employers’ sector and industry. Statistical significance: # p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Models 3 and 4 add the interaction terms of key interest, allowing the estimated effects of different forms of NSE on workplace well-being to vary by LGBTQ+ status. The interaction coefficients reveal that, consistent with Hypothesis 2, certain forms of NSE have a more detrimental effect on well-being amongst LGBTQ+ than non-LGBTQ+ workers. This can be inferred from negative and statistically significant coefficients on the interaction terms between LGBTQ+ status and part-time work (βadjusted = –3.04; p < 0.01 & βunadjusted = –2.15; p < 0.05), LGBTQ+ status and contract/fixed-term work (βadjusted = –3.48; p < 0.01 & βunadjusted = –2.75; p < 0.05), and LGBTQ+ status and other NSE (βadjusted =–17.28; p < 0.05 & βunadjusted = –12.90; p < 0.05). The interaction term between LGBTQ+ status and casual work is, however, not statistically significant. A similar pattern of results is observed in analogous models combining all forms of NSE into a single category (see Appendix Table A6).

Discussion and conclusion

Despite recent shifts in societal attitudes towards gender and sexuality, workplaces remain recognised sites for heteronormative and cisnormative pressures (see Ozturk Reference Ozturk, Forson, Healy, Öztürk and Tatli2024). As a result, people identifying as LGBTQ+ continue to experience multiple forms of labour-market disadvantage, including greater unemployment rates, lower wages and job satisfaction, and slower career progression (Drydakis Reference Drydakis2022a; Gedro Reference Gedro2010; Lacatena et al Reference Lacatena, Ramaglia, Vallone, Zurlo and Sommantico2024; Laurent and Mihoubi Reference Laurent and Mihoubi2017; Leppel Reference Leppel2014; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk, Tatli, Broadbridge and Fielden2018). Nevertheless, existing scholarship has paid little attention to the comparative employment conditions of LGBTQ+ employees (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024; Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023). This study contributed to filling this gap by examining the relationships between LGBTQ+ status, NSE, and workplace well-being. Drawing on a range of theoretical perspectives, we hypothesised two ways whereby NSE can interact with LGBTQ+ status and workplace well-being: (i) an extensive margin, with LGBTQ+ employees being comparatively more likely to work in NSE, and (ii) an intensive margin, with NSE exerting a more detrimental impact on the well-being of LGBTQ+ employees. To test these novel hypotheses, we leveraged unique Australian data from the 2024 AWEI Employee Survey.

Our initial results provide new empirical evidence in support of our first hypothesis. Using multinomial logistic regressions, we showed that LGBTQ+ workers are overrepresented in certain types of NSE – namely, fixed-term contract work and temporary/casual work. At the same time, LGBTQ+ individuals are less likely than non-LGBTQ+ individuals to engage in permanent part-time work – a form of NSE that could perhaps be argued to be less detrimental to employees given its non-contingent or permanent nature. With the exception of part-time work, our findings for Australia corroborate and extend those of Kinitz et al (Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023), who observed higher rates of temporary and irregular employment amongst LGBTQ+ people in Canada. While evidence on part-time employment amongst LGBTQ+ workers is less clear-cut, our results align with those of studies reporting a higher likelihood of full-time than part-time employment amongst lesbian women – a finding that has been attributed to lower rates of parenthood and more equal household divisions (Tebaldi and Elmslie Reference Tebaldi and Elmslie2006; Ueno et al Reference Ueno, Grace and Šaras2019).

The observed preponderance of NSE amongst LGBTQ+ employees is consistent with the predictions of minority-stress theory (Cancela et al Reference Cancela, Stutterheim and Uitdewilligen2024; Meyer Reference Meyer2003; Velez et al Reference Velez, Moradi and Brewster2013): the distal and proximal stressors experienced by LGBTQ+ workers may impair their ability to attain and retain sought-after employment forms – such as permanent full-time employment. It is also consistent with recent qualitative insights pointing to complex forces ‘pushing’ LGBTQ+ employees into NSE and other forms of low-quality and precarious employment (Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b). While our data do not allow us to identify specific stressors that contribute to the overrepresentation of LGBTQ+ employees in NSE, additional analyses suggested that industry and sector sorting can only marginally explain this. Therefore, putative mechanisms are likely to include discriminatory employer practices (Drydakis Reference Drydakis2022b) or LGBTQ+ workers’ self-selection to conceal their identities or limit the need for disclosure (Holmes et al Reference Holmes, Aydin, Johnson, Ozeren, Meliou, Vassilopoulou and Ozbilgin2024; Ragins Reference Ragins2008; Tilcsik et al Reference Tilcsik, Anteby and Knight2015), or a combination of both. Regardless of the underlying reasons, this overrepresentation of LGBTQ+ workers in NSE may help explain this group’s comparatively poorer career outcomes.

In the second part of the paper, we provided first-ever analyses of whether NSE differentially affects the workplace well-being of LGBTQ+ individuals, which we accomplished through a series of linear random-effect regression models. In doing so, we moved beyond existing research examining the prevalence of precarious employment amongst LGBTQ+ workers (i.e., Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Shahidi and Ross2023), proving also into its intra-worker well-being consequences. Consistent with Owens et al (Reference Owens, Mills, Lewis and Guta2022) findings for Canada, our results indicate that LGBTQ+ employees who work in NSE exhibit lower levels of well-being than LGBTQ+ employees in standard employment. In alignment with our second hypothesis, they also offer novel evidence of an excess negative effect of some types of NSE on the workplace well-being of LGBTQ+ employees. Of particular relevance was the finding that fixed-term employment and permanent part-time work bear a larger negative effect on the well-being of LGBTQ+ compared to non-LGBTQ+ employees. This pattern of results aligns squarely with invoked theoretical principles from cumulative-disadvantage perspectives (DiPrete and Eirich Reference DiPrete and Eirich2006; Merton Reference Merton1988) and the stress process model (Pearlin et al Reference Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman and Mullan1981), suggesting that the labour-market-related disadvantages stemming from the stigmatised LGBTQ+ status interact with those stemming from working in generally-less-desirable NSE, yielding multiplicative negative impacts. The results also echo recent qualitative scholarship identifying cyclical processes involving involuntary labour-market exits and precarious employment amongst LGBTQ+ employees, which iteratively deplete their mental health (Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen and Gesink2024c).

These findings suggest that for LGBTQ+ workers, the disadvantages associated with part-time and fixed-term work far outweigh their potential benefits, resulting in a net negative effect on their workplace well-being. Future research could aim to identify the specific features of these forms of employment that contribute to the observed well-being deficits. Based on the literature, it is plausible that fixed-term and part-time employment expose LGBTQ+ employees to a greater risk of economic insecurity, either because of their short-term nature or because of insufficient work hours (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2015). Economic insecurity can interact with, and further compound, other stressors experienced by LGBTQ+ employees within and outside the workplace (Meyer Reference Meyer2003). While temporary/casual employment should also heighten the risk of economic insecurity, some have documented that casual workers in Australia often engage in so-called ‘permanent casual work’ arrangements that offer them some level of continuity and certainty (McCrystal 2020; Peetz and May Reference Peetz and May2022). Further, some studies have highlighted the potential benefits of casual employment – such as fewer employer demands (Hahn et al Reference Hahn, McVicar and Wooden2021), which could offset the negative impacts of this type of employment arrangement on LGBTQ+ workers’ well-being. More broadly, our findings suggest that the effects of NSE on workers’ well-being depend not only on the nature of the employment arrangement but also on the characteristics and circumstances of the workers subjected to these arrangements. Although previous studies have highlighted the benefits of fixed-term and part-time work for some subgroups – such as employees with caring responsibilities (Booth and van Ours Reference Booth and van Ours2009), our study shows that, on average, these arrangements are more detrimental to the well-being of LGBTQ+ employees.

While this study has generated new and important insights into the employment conditions of LGBTQ+ employees, it is not without limitations to be addressed in future research. Given the voluntary and non-probabilistic nature of the 2024 AWEI Employee Survey, participating employers and employees are likely to be positively selected and not nationally representative (Perales Reference Perales2022). Thus, our results likely provide ‘best case scenario’ estimates regarding the workplace experiences of LGBTQ+ workers. Future research could aim to replicate our findings using probabilistic samples to ascertain their broader generalisability. Relatedly, the 2024 AWEI Employee Survey does not collect data on respondents’ occupation, educational attainment, and other work and employment characteristics beyond those utilised in our models. The absence of this and similar information might potentially lead to instances of omitted-variable bias and also preclude us from digging deeper into the specific mechanisms underpinning the reported relationships. Future studies may thus wish to explore how these and other factors contribute to both the overrepresentation of LGBTQ+ people within certain types of NSE, as well as their vulnerability to its deleterious consequences. This may include analyses of fit-for-purpose surveys or qualitative data focusing on, amongst others, employees’ social support, job autonomy, workplace culture, organisational inclusivity – including hiring and retention policies and practices (Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b; Ozturk and Tatli Reference Ozturk, Tatli, Broadbridge and Fielden2018). Finally, the present study’s focus on employees – who account for 85% of workers in Australia (ABS 2024) – creates a need for additional research examining alternative forms of NSE, such as self-employment and ‘gig work’.

Despite the potential for expansion and refinement, our study contributes new and important insights into timely debates on labour-market inclusion and the features and consequences of NSE. Critically, our findings demonstrate that LGBTQ+ workers face a ‘double whammy’ in relation to NSE: they are not only overrepresented in problematic types of NSE but also more negatively impacted by NSE arrangements. More research into potential solutions for this situation is warranted. In the meantime, existing knowledge suggests potential levers (for a recent systematic review, see Gould et al Reference Gould, Kinitz, Shahidi, MacEachen, Mitchell, Venturi and Ross2024). In addition to strengthening legislation aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of NSE on all workers (see ILO 2016), policies that ensure that LGBTQ+ individuals are not disproportionately disadvantaged by NSE are urgently required. Such policies could address the pathways through which LGBTQ+ people find themselves less able to secure permanent full-time employment. For example, employers can enact stricter controls on the suitability of their HR practices for diversity and equity in hiring and promotion (Day and Greene Reference Day and Greene2008). This may involve employers applying gender-equity targets (including ‘40:40:20’ models, Risse (Reference Risse2024)) not only to their overall workforce but also to jobs with the most desirable employment conditions (particularly, permanent full-time employment). In addition, policies that mitigate the excess negative effect of NSE amongst workers identifying as LGBTQ+ are required. For instance, onboarding processes for new staff should be standardised across employment types. This would ensure that all workers are informed about the organisation’s employee/ally networks and equity-and-diversity initiatives. Facilitating access amongst LGBTQ+ workers in NSE to health-related employer provisions (such as gender-affirming surgery/therapies and/or mental-health leave) may also be important (Webster et al Reference Webster, Adams, Maranto, Sawyer and Thoroughgood2018). Targeted qualitative studies on the experiences of LGBTQ+ workers in NSE (see e.g., Kinitz et al Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen, Fehr and Gesink2024b, Reference Kinitz, Ross, MacEachen and Gesink2024c) are required to better elucidate the mechanisms generating these associations and, in turn, the appropriate remedial actions required from employers. Importantly though, our findings make it clear that, in the absence of decisive action, LGBTQ+ workers will remain at the receiving end of NSE’s ‘double whammy’.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1035304625000080.

Funding statement

This research was supported by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (Project ID CE200100025).

Competing interests

Francisco Perales and Christine Ablaza report no conflicts of interest. Nicki Elkin would like to disclose working at ACON Health (a not-for-profit organisation committed to diversity and inclusion in the workplace), which collected the Australian Workplace Equality Index Survey data used in this study. This role, however, has no bearing on the objectiveness of their contributions towards the present study.

Christine (Tin) Ablaza is a Lecturer in Social Economics at Flinders University and an Honorary Research Fellow at The University of Queensland’s Centre for Policy Futures. Tin uses advanced quantitative methods to explore various forms of socioeconomic disadvantage, with a particular focus on contemporary forms of labour market disadvantage in Australia and internationally.

Francisco (Paco) Perales is Adjunct Professor of Social Policy at Griffith University. He is also The Australian Research Awards 2023 ‘Best in the Field’ for the discipline of Sociology, and one of the top 2% most-cited researchers worldwide. Paco has a long track record of academic work in the space of gender and sexuality, including multiple research studies conducted in partnership with Pride in Diversity and using the AWEI Employee Survey.

Nicki Elkin is Associate Director of Quality Training and Research at ACON Health’s Pride Inclusion Programs. Nicki works with a wide variety of organisations to help them develop and deliver LGBTQ+ inclusions strategies to support LGBTQ+ people in the places that they work, and leads the research activities across the division, including the development of the Equality Indices used to drive organisational inclusion initiatives and measure their impact.