1. Croker’s demesne

At first glance, Glencairn Castle in Dublin County, Ireland might seem like an odd monument to nineteenth-century democracy in America. The “great house” had the look of a Gilded Age mansion oddly crowned with medieval flourishes (Figure 2). Centered by an Irish battlement tower, and surrounded by a fortified roofline, it was as if an up-jumped feudal lord had earned a fortune by speculating in Manhattan real estate. Inside were all the trappings of an aristocratic life: six family bedrooms, a grand hall, study, and library, a Japanese Room with tapestries, a billiard’s room, and a chapel with a vaulted ceiling. The 500-acre environs boasted picturesque rivulets and glens, a conservatory to raise orchids, a walled fruit garden, and a croquet yard for leisure. Its stud farm housed Orby, winner of the English Derby, along with a dozen other thoroughbreds.

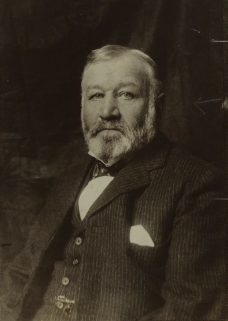

Richard Croker of Tammany Hall, New York City’s regular Democratic Party, retired to this sprawling Irish manor in 1905 (Figure 1).Footnote 1 There, he took on the duties of a country gentleman by employing a small army to serve the estate, by funding charities, and by resolving local disputes.Footnote 2 Tammany Hall’s electoral turf was truly worlds away from Croker’s demesne in the lush Irish countryside. His New York political organization represented the densest urban neighborhoods on the planet; lower Manhattan was overcrowded with immigrant proletarians working daily for industrial wages (Figure 3). From this Great Metropolis, Richard Croker extracted wealth with the calculated genius of a powerful baron harvesting the spoils of mass suffrage.Footnote 3

Unlike feudal barons from days of yore, however, Tammany Hall was an avowedly capitalist enterprise. In 1899, Richard Croker once stated flatly to investigators of the Mazet Committee that he was “[a]ll the time” working for his own pocket, “same as you.”Footnote 4 Tammany had already minted the personal fortunes of two generations of party leaders by the 1890s.Footnote 5 And yet, in the style of Glencarin’s odd crenelated roof, Croker’s businesslike approach to politics was also steeped in, and self-consciously referential to, an older tradition than the modern drive for profit.

When Boss Croker mounted a public defense of Tammany Hall, he did so on very different grounds than invocation of commercial self-interest. Writing in the North American Review, a fashionable literary magazine, Croker explained that his organization worked to preserve the values of hierarchy, order, and loyalty within a “system of deferential compromise.”Footnote 6 How could Tammany be so vilified in the court of respectable opinion, Croker supposed, when clientelism was a cherished tradition deeply embedded within the country’s own representative institutions? The magazine’ Gilded Age society audience might have hemmed and hawed, as Protestant U.S.-born middle-class readers wary of Tammany’s working-class, Catholic and immigrant electorate. But many contemporaries, beginning with elite reformers, conceded Croker’s basic point about historical legacy.

Figure 1. Richard Croker of Tammany Hall.

Figure 2. Glencairn Castle.

Figure 3. Packed Streets on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, 1910.

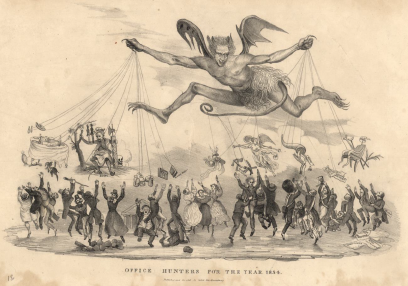

Figure 4. Office Hunters for the Year 1834.

To explain Croker’s demesne, we need a framework for thinking about how long-term inheritances of social inequality shaped American officeholding politics. I argue the old American state should be understood as a republic of patrons and clients during the Long Nineteenth Century. From the late colonial era to the New Deal, politics was never quite feudal, in the medieval sense, although arrangements relied upon a renovation of monarchical lineages of patrimonial dependency. Nor were the spoils of office fully capitalist, even if by mid-century patronage was highly commodified, and premised upon the asymmetric exchange of material benefits. Unlike aristocratic societies, clientelism was never by hereditary title, even when practitioners assumed that society was organic and that inequalities were natural. Leveraging public authority for personalistic and party gain was fundamental to governance. Yet, the advent of mass politics made goals of capital accumulation conditional upon electoral competition for control over the state’s bounty. The country was a “mixed” polity, in the parlance of the time, invoking a balance of different forms of authority.Footnote 7 “It is not Democracy—nor Aristocracy, nor monarchy,” explained John Quincy Adams, “but a compound of them all.”Footnote 8 The “compound” quality of the American state during its classical age deserves another look.

Reinterpreting clientelism in American political development helps to explain why the century’s democratizing currents were often tempered and redirected. To make this case, first, I situate patron–client relations within an Orrenian “belated feudalism” framework, arguing that patterns of officeholding patrimonialism embedded social inequality into republican institutions. Then, I outline the racialized and gendered penumbra of the old American state, and its relationship to formal political representation. Early moments in U.S. state formation presented not only rupture with monarchy but also adaptation of old modes of governance. For this reason, I detail the feudal lineages of the American “spoils system” going back to the late colonial period and the early republic. Officeholding political economy during the Long Nineteenth Century was central to party formation. Thus, in the following section, I explore the honors and emoluments associated with customary officeholding practices, which explains how many politicians became propertied as part of their structural position during the old republic. By mid-century, the intimate political household organized around ties of affective dependence had become bureaucratized by the rise of mass politics. Markets for patronage transformed from the personal discretion of gentlemen to the coalitional brokerage of party leaders. The essay concludes by assessing the legacy of clientelism in American political development. Scholars might consider whether core features of the old republic have simply disappeared over time or whether customary elements have persisted into the modern era, for instance, when it comes to officeholding emoluments.

2. Belated feudalism revisited

Essential features of the nineteenth-century state are no longer the enigma for scholars that they were just a few decades ago. Building a New American State, now a classic in the field of political development, emphasized the weak capacity of national government during this period’s decentralized patchwork of “courts and parties.”Footnote 9 William Novak’s “well-regulated society,” by contrast, countered that governance was robust but located primarily at the state and local level.Footnote 10 The “associational state” foregrounded the role of civic forces in mobilizing private networks for an expansive array of public purposes, although less has been noted about voluntarism’s patrimonial imprint.Footnote 11 Richard Bensel’s “Yankee Leviathan” concept advanced the Civil War as a critical juncture in the creation of an empowered fiscal-military state.Footnote 12 Each of these approaches capture key dynamics of the republic’s classical age before major restructuring during the twentieth century.Footnote 13

Questions linger, however. What accounts for the relative stability of the old American state across the Long Nineteenth Century, a period of momentous change? The United States experienced an epochal shift from an agrarian settler society with legible boundaries into an abstract national polity governed by impersonal economic and bureaucratic forces. Second, how can we make sense of democratization amidst the appearance of novel kinds of capitalist inequality? Democracy and capitalism are two highly combustible elements of political economy. In the former, “the people are turbulent and ever changing.” With the latter, “all that is solid melts into air.”Footnote 14 Mass suffrage and party competition, imperial aggrandizement, inter-continental migrations, and the construction of a slaveholders’ republic followed by uncompensated emancipation and Reconstruction—all left open the very real prospect that the United States might cleave into pieces or simply dissolve into incoherence. By the turn of the twentieth century, the United States had become an industrial behemoth; economic booms were bigger, but so were the busts. Whether a polity like this could govern peoples of varied origins and civic status across far-reaching terrain was a constant anxiety of political leaders.Footnote 15

The origins and development of clientelism are a good place to begin answering questions about the relationship between social instability and political economy. For this, we need renewed attention to how historical actors rejected, adapted, and remade longstanding monarchical inheritances. Many forms of social order derived from Europe—feudalism, for instance—did not simply disappear with colonial settlement in North America or the American Revolution. Historians typically consider feudalism to be an archaic form of vassalage specific to medieval Europe.Footnote 16 It can also be conceptualized, however, as a distinct form of governance. Feudal relations organize social institutions around presumptions of naturalized inequality where the right to rule is based on ascriptive characteristics. An essential component of every feudal regime is not self-ownership and individual autonomy, as in liberalism, but rather collective dependence in relation to a patriarch. Many of the qualities of American party politics and officeholding, including its patrimonial style and mercenary character, emerged out of a feudal shell.Footnote 17 In this study, the term feudal refers to a set of principles and political relations and not to their original historical setting.

From a theoretical approach, then, “belated feudalism” endured in pockets of American life at least well into the twentieth century. Karen Orren, for example, has written about the subsumption of manorial authority, guild rights, and medieval social rank into American common law.Footnote 18 Up until the New Deal, the medieval master’s authority over servants was lodged in the judiciary as the employer’s private dominion over workers. The judicial realm was hardly unique. Whether slavery should be considered an antique vestige of domination—an “imperfect” feudalismFootnote 19 and “premodern” social orderFootnote 20—or as the dynamic greenshoots of an emerging racialized capitalism, is an ongoing debate.Footnote 21 The question of whether plantation slavery was capitalist, however, is arguably distinct from how it achieved political legitimation. To southern ideologists, slavery was a “domestic” institution organized around the monarchical prerogatives of a White patriarch, an “office not sought” but inherently endowed by supposed racial superiority.Footnote 22

Beyond labor law and slavery, the family was also a pre-liberal realm. Eileen McDonagh has noted that family relations during the nineteenth century drew from direct parallels with monarchy and aristocracy; many post-colonial countries with European lineages have material and symbolic links between patriarchal household care and the historical development of state benevolence.Footnote 23 The family was not a unit of political rule based upon consent so much as from hierarchies acquired at birth that were perceived as a natural form of inequality.Footnote 24 In the oeconomical realm of “private relations,” masters, husbands, and parents were considered not only citizens but also private authorities who exercised governance.

Judges deferred to private hierarchies where figures with patriarchal positions held traditional rights to authority over dependent wives and children.Footnote 25 This was because, as Paula Baker explains, “distinctions between family and community were often vague; in many ways, the home and the community were one.”Footnote 26 Americans “looked to family relations as a political mode,” even as views about the proper roles for White men and White women were heavily contested by section and party with the rise of mass politics; Whig-Republicans advanced a moral role for woman in guiding “benevolent” government action, whereas Democrats tied marriage and slavery to “domestic” institutions in which the federal government had no right to interfere.Footnote 27 Familial inequality was one of the “ancient hedgerows,” as Karen Orren put it, around which the Constitution of 1789 and the antebellum state of “courts and parties” were constructed.Footnote 28

Clientelism was an expression of belated feudalism that grew out of the patrimonial household. Scholars typically think of clientelism as a particularistic distribution of material benefits in return for political support.Footnote 29 Indeed, the spoils system that took hold between the Jacksonian era and the Gilded Age exploited public administration for partisan electoral gain.Footnote 30 There is hardly a better example of instrumentalism in politics than the use of patronage to win elections. But that prevailing approach is also too narrow. Clientelism was never understood by historical actors as a mere appendage of partisanship. Nor were political ties so limited or superficial as mere transactions in an anarchic marketplace.

Rather, clientelism was an intimate economy that organized social power and political representation around perceived gradations of racial, gender, and class difference. A reciprocal hierarchy of social, economic, and political emoluments was shared unequally between a patron and clients, whether it be individuals, friends and family, or party organizations. What bound them all together—as sticky social units continuously made and unmade—were patrimonial expectations of loyalty, service, and deference in return for material rewards. Formal and informal social control was “coupled” through elite networks that pulled upon hierarchies to reproduce order through political institutions.Footnote 31 Many challenges from below during the nineteenth century became nested in reorganized hierarchies of dependence, for example, early trade unions, Black men after emancipation, and women officeholders before the Nineteenth Amendment. In this way, feudalism was renovated for a federal republic.

3. Republic of patrons and clients

Political rule in the old republic was obscured by a range of shadows cast over three distinct realms. There was an official zone expressly organized by written constitutional arrangements and congressional initiatives. This was the public record of statesmen as they interpreted, experimented with, and sometimes invented, legislative, executive, and judicial powers. In a formalized public sphere, leaders passed laws, created civic rituals, and invented national symbolism that was crucial to the post-colonial state-building project.

The second realm consisted of the hazy arena of political “management,” as it was often derisively called. Hidden proximately behind powerful leaders were lesser luminaries, party agents, and hangers-on, along with various civic and business figures who managed the backchannels of public affairs. Under this shadow, factions, juntos, and parties became arenas of deliberation and decision-making. As E.E. Schattschneider famously observed, informal mechanisms of coordination arose by necessity outside the confines of constitutional structures.Footnote 32 Presidents formed a “kitchen cabinet” of handpicked advisors. In Congress, the Speaker’s private discussions with allies or political caucus began to set a policy agenda.Footnote 33 Correspondence, local meetings, and conventions relied heavily on interpersonal relationships to nominate candidates and conduct party affairs.Footnote 34

It was not until gradual implementation of civil service reform, beginning with the Pendleton Act of 1883, that parties were prevented from exploiting public administration for private political uses.Footnote 35 The “lodge democracy” of fraternal political organizations during the mass party era reconciled elite-led mobilization with the energies of common White men. The inner sanctums of political committees, however, lay ambiguously between a closed social club—with all its ascriptive presumptions about race and gender—and a mass civic association.Footnote 36 During the Gilded Age, “rings” of officeholding entrepreneurs found ingenious ways to extract economic windfalls by using political institutions to speculate in business.Footnote 37 Public law only began to reform party activity by regulating nominations and ballot access in the Progressive Era.Footnote 38 Parties exercised all sorts of private discrimination until the Supreme Court ruled against explicit racial exclusion in Smith v. Allwright (1944). Before the twentieth century, internal party operations were conducted like extensions of a patrimonial household, the activities of which were often obscured from public view.

A great deal of the politics studied by historians and political scientists took place within these proximate shadows of political management. Margaret Bayard Smith, Dolley Madison, and other elite women working behind the scenes emerged as powerful brokers of federal patronage in the national capital during the Jeffersonian era.Footnote 39 Meeting officeseekers discretely in parlors under ostensibly social auspices helped to populate administrations with political supporters while guarding husbands and relatives against charges of favoritism, nepotism, and corruption.Footnote 40 Henry Clay’s entourage later in the 1830s and 1840s included acolytes from around the country, but none more loyal than his Kentucky protégé, John J. Crittenden. This “friend” was so dutiful that Crittenden once delivered up his own U.S. Senate seat to advance Clay’s presidential aspirations, a choice practically unthinkable from the standpoint of the radical individualism presumed by Ambition Theory in officeseeking.Footnote 41 When U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling expressly forbade Chester Arthur from accepting the 1880 Republican nomination for vice president, but Arthur did so anyway, it sparked a crisis that threw Republicans out of power in New York State and posed an existential threat to the Garfield Administration.Footnote 42

Many political ties were never considered equal during the nineteenth century among the councils of powerful White men, even as suffrage expanded after the 1820s. To assume that they were in practice would ahistorically flatten the complexity of clientelistic relations. Asymmetrical roles expressed through the language of familial affection were an ever-present but rarely publicized element of patrimonial officeholding.

A third, expansive domain of the old American state encompassed the penumbra of White male representation—those racialized and gendered social dependents who made up a majority of people living in the United States. These people were to be neither seen nor heard from the standpoint of republican institutions. To understand this penumbra, we must look to the remarkably rigid hierarchy of civic belonging during the Long Nineteenth Century. People experienced life through unequal social positions of ascribed difference in the family, community, and polity. Cold War-era scholars like Louis Hartz once argued that the absence of a landed aristocracy in the United States paved an early road to liberal hegemony.Footnote 43 But America was not a society of rights-bearing civic equality for women, children, servants, the enslaved, and the Indigenous—not in terms of norms, legal status, or representation.Footnote 44

The existence of those living in the Old Republic’s penumbra was expressed only indirectly through governing institutions as propertied relations of political and ideological “dependence” to a White male patriarch.Footnote 45 Gretchen Ritter explains, “when free white men entered the public realm, they met there as members of the social compact and as liberal individuals enjoying equal rights. But in their households, they were republican masters.”Footnote 46 Historical actors themselves understood politics as the struggle for a place in society beyond the domination or exploitation of others. For this reason, a major goal of Black abolitionists and women’s rights advocates was to emancipate themselves from the depths of this republican penumbra and to carry their own resolve into public affairs.

In the Jeffersonian tradition, the genius of republican government was secured by the civic independence granted by land ownership. To be acknowledged as a Lockean subject capable of self-government, by definition, presumed being a White property-bearing male head of household.Footnote 47 Expansionist federal policy was therefore principally about engineering majority White populations in Native territory through land transfers to male settlers.Footnote 48 The titular White male head of household could then expect to be served by an intimate court of “lesser” dependents at home, on the farm, in the workshop, or on the plantation.Footnote 49 Historical oeconomics are thus crucial to understanding the political development of clientelism.

The reason is because capitalism in America emerged out of the extended household and its unequal terms of status, obligation, and reward. The northern “free labor” farm, with its subsistence and composite agriculture, the mercantile house, which built international trade links, the banking house, and its ties to financial markets, the artisanal workshop, from which manufacturing emerged, and the plantation system of slavery—each of these pillars of the increasingly capitalist economy emerged from patrimonial enclaves. A household was not just the direct familial unit subject to patriarchal rule, but also those wage workers, domestic servants, and enslaved people who labored in the penumbra. Such domains were unevenly distributed, to be sure. Many White men remained propertyless or nearly so, especially after economic panics in 1837, 1857, 1873, and 1893. Mid-century capitalist trends like proletarianization and urbanization also generated a crisis of the Jeffersonian ideal. Waves of labor republicanism, first in the 1830s, and then the 1860s and 1880s, carved out spaces of non-domination by expanding suffrage rights, overturning slavery, and promoting collective advancement through associational politics, mass protest, and trade unions.Footnote 50 So did the demands of Black freedmen and freedwomen for land redistribution and equal rights during southern Reconstruction.Footnote 51 But the nineteenth-century social world remained primarily a struggle over autonomy understood as a spectrum from dependence to independence.

Ultimately, the greater host of clients were not found among elite parlor women or the Crittendens and Arthurs, the lieutenants of statesmen. Most clients were instead submerged several gradations deeper into the shadows beyond the res publica itself. Charles Dupuy, an enslaved man, followed Henry Clay to the capitol as a valet like his father, Aaron, before him. The Dupuys traveled across the country to serve the “Great Compromiser,” thereby making possible his storied political career. Dupuy the younger helped to manage the Ashland plantation back at home in Kentucky where, in Henry Clay’s lifetime, 120 Black men and women were enslaved as part of a diversified portfolio that included land speculation and investments in nascent manufacturing. The elder Dupuy and his wife, Charlotte, were sent with James Brown Clay to Portugal from 1849 to 1850, after James’ appointment as chargé d’affaires was secured by the influence of his famous father. Earlier in life, Charles’ mother, Charlotte, had petitioned the courts for her freedom without success.Footnote 52

People enslaved by Henry Clay stood not just off to the side of the public arena but beyond all civic recognition. Even in this realm, of course, the patrimonial household was contested. Ona Judge fled captivity from George Washington’s household during his presidency.Footnote 53 The women of Lowell, Massachusetts halted work at the looms to demand better treatment from the Whig patriciate in the early days of industrialization.Footnote 54 Still, the American polity collapsed into a personalized zone of governance wherever the family met the state through the extended household.

4. Lineages of the patrimonial state

Elite reformers during the Gilded Age understood clientelism as an inheritance from which they sought to make a clear rupture. In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes charged Dorman B. Eaton, chair of the American Civil Service Commission, to publish an official account of the spoils system and to investigate the potential for appointment by merit.Footnote 55 Political parties hungry for patronage had entrenched themselves in the nation’s custom houses, postal service, and other organs of federal administration. Locally, the dilemma was also acute. Party organizations had implanted within the governing structures of rapidly growing industrial towns and cities.Footnote 56 Hayes was the first president to risk any political capital by taking at least halting steps toward the reform of partisan national administration.Footnote 57

An obvious place for Dorman Eaton to begin with a history of the spoils system might have been Andrew Jackson’s announcement of “rotation in office” during his first State of the Union Address; or, perhaps, with William Marcy’s declaration before the U.S. Senate in 1832 that “to the victor belong the spoils.”Footnote 58 Instead, in his report to President Hayes, Eaton, a Harvard-educated railroad lawyer from a prominent New England family, drew upon English whig historiography. He traced the problem all the way back to the “feudal spoils system” of the medieval British Isles and the evils of centralized patronage under the early modern English crown. For Dorman Eaton, the origins of the American crisis in the 1870s and 1880s lay far earlier in British political development.Footnote 59 Colonialism had carried the practice of governing with royal patronage to the shores of North America, and with it, officeholders who hoped to turn a quick profit before returning to the metropole.Footnote 60

Picked up and reinvented by Eaton’s generation of reformers, this “whig science of politics” had permeated thinking about officeholding during the late colonial period and early republic.Footnote 61 Antifederalists like Cato warned ominously at Ratification that establishing a new chief executive with powers of appointment would approximate, and perhaps recreate, the follies of monarchy. The presidency would essentially constitutionalize the king’s “numerous train of dependents.”Footnote 62 Early modern states in Europe were built outwards through war and marriage and inwards by centralizing royal authority over feudal lands; English monarchs, for example, had aggrandized executive power by distributing lucrative offices to manage Parliament. Whig critics of royal authority argued that corruption arose from those “intimate obligations” associated with a private realm of generosity, the practice of which signified an honor; that is to say, a public fixture of social rank.Footnote 63 From this English whig interpretation, then, officeholding remained dangerous even in a republic where free-born citizens owed no allegiance to the crown.Footnote 64 There is perhaps no better depiction of this idea than the anti-Jackson cartoon “Office Hunters for the Year 1834” (Figure 4) which portrays the president as a manipulative devil pulling strings to make people across the society jump to his will.

The American president was no monarch draped in the divine legitimacy of hereditary rule. Nevertheless, the Constitution of 1789 placed monarchy’s implied powers of discretion into the hands of a single executive, along with a legislative veto and the sword. Crucially, new presidential powers also included the right to bestow lower administrative office. Executive patronage had been part of a royal tradition of protection and beneficence.Footnote 65 Anti-Federalists warned that under the command of a domineering president, subordinate officeholders might be tempted to trade liberty for political dependence. No matter how limited, the personal rule of executives fit awkwardly with republicanism as a government “of Laws and not Men.”Footnote 66 Classical whig theory placed subservience to the will of a single individual, a national patriarch, in sharp contrast to the rule of law negotiated in open debate by a legislature chosen by the people. Would grasping executives now use “monarchical” discretion to erect a tyranny? The more extensive the offices controlled by an executive, according to the whig critique, the greater the influence to bribe, intimidate, or degrade the entire community.Footnote 67 Such concerns were part of the Constitution’s logic in prohibiting aristocratic title and the acceptance of foreign gifts.Footnote 68 The afterlife of monarchy—executive discretion in public affairs and patronage—might live on as a potential source of corruption even in tamed republican form.

Cato was prophetic. Executive patronage was ever present in national politics. As early as 1796, Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison denouncing the establishment of a postal road from Maine to Georgia that would “be a source of boundless patronage to the executive, jobbing to Members of Congress & their friends.”Footnote 69 Andrew Jackson’s allies in 1828 stitched together a national party coalition through the active support of federal officeholders, especially in the post office, the republic’s largest and most geographically extensively federal presence.Footnote 70 Henry Clay made campaigns against “a principle which wears a monarchical aspect” the basis for a coherent opposition “whig” party; his first speech in the Senate criticizing President Jackson was a lengthy denunciation of the spoils system.Footnote 71 Wartime presidents like James Polk and Abraham Lincoln filled the army with politically reliable generals.Footnote 72 President James Garfield was assassinated by Charles Guiteau precisely because the Gilded Age party system depended upon the factional division of spoils. At the height of Jim Crow, the “rotten boroughs” of southern Republican state parties often supplied the decisive convention votes required to nominate presidential tickets.Footnote 73 The officeseeking host permanently trailing the presidency was “enough to sicken one of public life,” wrote one prominent Whig party leader in 1840. “How wretched he, who hangs on prince[’]s favors.”Footnote 74

And yet, executive patronage shorn of a broad political base proved to be incompetent. John Tyler in 1844 and Andrew Johnson in 1868, two partyless creatures, discovered that it was impossible to propel reelection ambitions with spoils alone. Even popular presidents in good party standing claimed nothing close to a monopoly on executive offices. The Constitution of 1789 bound nominees by legislative “advice and consent.” In good whig practice, appointed officials informally served congressional parties at least as much as presidents, if not more. During the Second Party System, the surest way to a federal appointment was through the recommendation of a member of Congress, or a cabinet official who had been a U.S. Senator. The Tenure of Office Act years between 1867 and 1887 were famously coercive of executive power on appointments, requiring a vote in the Senate for removal as well as confirmation. Hard limits to presidential authority suggest that royal prerogative in bestowing “honors” was successfully republicanized.

But that monarchical inheritance also endured through officeholding’s link to clientelism. Instead of one Caesar, America’s decentralized fragmentation produced a dispersed, loosely connected set of lesser patrons like Richard Croker of Tammany Hall. “The superstition of divine right has passed from a king to a party,” George W. Curtis lectured the National Civil-Service Reform League in 1892. “[T]he old fiction of the law in monarchy that the king can do no wrong has become the practical faith of great multitudes in this republic in regard to party.”Footnote 75 Indeed, victorious parties presumed something akin to a party “right to office” under the spoils system. City and state bosses of the party period aspired to lord over parochial enclaves by grasping at whatever power they could amass through appointments, contracts, franchises, charters, and other uses of public authority. The old radical whig fear of that “baneful poison” of patronage was just as likely to explode over appointments to a local public works department or state canal commission as over federal “plums” like the custom house.Footnote 76 Fiscal and administrative capacity in the nineteenth century developed the fastest among state and local authorities. Subnational officials experimented with a host of quasi-public tools, from the chartering of banks and corporations to the building of vital infrastructure and adventures in public debt-financing.Footnote 77 Amidst a polity expanding by leaps and bounds, the stakes multiplied exponentially in state and local politics over who would control, distribute, and benefit from the proliferation of public offices.

For these reasons, Richard Croker’s defense of clientelism in the pages of North American Review rings true. If any political force in the United States at the dawn of the twentieth century could legitimately stake claim to represent the dynastic legacy of an ancient house of the American republic, it was Tammany Hall. What made Tammany unique was not its status as a so-called fountainhead of corruption, as many critics charged, or even its alien social base, which enraged anti-Catholic opinion. Clientelism was the dominant political relation in American political institutions throughout the Long Nineteenth Century. And yet, only Tammany Hall could boast to a continuous organizational existence.Footnote 78 That was the Tammany difference.Footnote 79 Others came and went. Only Tammany endured—a common refrain of drunken toasts at social gatherings. The Hall celebrated its centennial during Croker’s reign.

5. Officeholding political economy

Officeholding was a reliable means of embourgeoisement during the Long Nineteenth Century. Officeholding political economy ran on a mix of honors and emoluments that arose from customary practices and traditional usages inherited from monarchy. Political appointments were “not patronage,” lectured the Gilded Age political boss U.S. Senator Roscoe Conkling to Edwards Pierrepont, an ambitious corporate lawyer and future attorney general. Rather, in Conkling’s view, they were “exaltation.”Footnote 80 Official position conferred favored status during an era when individual “reputation” was how communities interpreted the fluidity of social rank.Footnote 81 Orlando Bloom, a Kentucky officeseeker in the 1840s, explained: “The strong nature with me is a desire to leave my children a name, at least, of some little honor.” A position like Governor of Iowa Territory, Bloom wrote to his patron, would “add the letter of Government…to distinguish us from the millions who hear our name.”Footnote 82

The meaning of officeholding, of course, was historically specific and sometimes contested. Wealthy gentlemen complained bitterly about the “vulgar” culture of “blatant officeseeking” that emerged in the wake of suffrage expansion during the Second Party System.Footnote 83 A similar protest arose in the south during the Civil War and Reconstruction. The prospect of Black men holding office for the first time became a major propaganda tool when the Union’s political legitimacy itself was disputed by the southern White population. Read against the grain, however, strenuous objections like these highlighted real stakes as people understood them at the time. The allure of public distinction remained a powerful draw throughout the Long Nineteenth Century, despite loud protests to the contrary.

There were very practical reasons why. Even minor officeholding elevated the status of a newspaper editor, merchant, or lawyer above competitors. Until the era of commercial advertising, an editor’s cultivation of political patronage was the most common way for newspapers to establish stable readership and subscriptions.Footnote 84 In the 1790s, the post office became a haven of Federalist party-aligned printers, merchants, and innkeepers. Entrepreneurs who operated at key nodes in the circulation of information, goods, and travelers welcomed the steady income and a way to boost provincial family business with an official status.Footnote 85 Amos Kendall, who later became Jackson’s Postmaster General in 1835, purchased his first job as town postmaster after the War of 1812 to financially support a share of the Minerva, the newspaper of Richard M. Johnson, a congressman from Kentucky who became his local patron.Footnote 86 Remarkably, arrangements based on officeholding property and even kinship were still in place in some locales as late as the Great Depression.Footnote 87 In 1939, one party broker requested a postal appointment in Albuquerque, New Mexico be transferred from father to son like an inheritance. The postmastership had been controlled by the same Putney family for 35 years. The position brought “considerable business” to their dry goods store, and allowed them to serve “acting practically as bankers…there for everybody in the little community.”Footnote 88

Dynamics were similar in the legal profession. Timothy Pickering’s rise to prominence as a member of the Massachusetts Bar was “affirmed” by Salem town election as selectman in 1772; Pickering later went on to serve in the Washington and Adams Administrations, and to build the Federalist Party.Footnote 89 At mid-nineteenth century, before running the Central Pacific Railroad or serving in the U.S. Senate, Leland Stanford operated a frontier courthouse out of his saloon in Cold Spring, California. There, he adjudicated petty mining claims and property disputes. But he only established himself there after failing to do so in a small Wisconsin town where his political career hit a dead end.Footnote 90 Being one of the rare Black lawyers in the South during the 1870s and 1880s meant something far more significant that just occupation alone. Joseph E. Lee was a general broker, community leader, and conduit for business in Florida between 1887 and 1913, holding numerous offices from municipal judge to state senator to port collector.Footnote 91 One of the first Black lawyers admitted to the Florida bar, Lee handled legal cases like administrative issues, divorces, land sales, and disputes involving “over 100 pounds of moose.” At the same time, he was also active in acquiring religious books, establishing fraternal organizations, settling teacher pay, and engaging in personal business.Footnote 92 Public officeholding was a common path to stature for lawyers in nineteenth-century communities.

Officeholding’s greatest allure, of course, were the emoluments. Public office was treated as a fungible form of property at a time when the line between public property and the private household domain was thin, if any line existed at all. Early congressional debates over presidential removals left the issue of officeholding property unresolved.Footnote 93 Interpretations about decorum were ultimately left to those elite gentlemen considered “fit” for office during the First Party System. Practices defaulted to customary usages and local traditions like nepotism, patronizing allies with hiring and contracts, clandestinely subcontracting out undesirable tasks, and doing favors on government time.Footnote 94 Later party leaders and local committees of the Second- and Third-Party Systems were far less ambiguous than statesmen who rhetorically denounced favoritism while faithfully serving allies in private.Footnote 95

Grassroots partisans spoke freely and with urgency about what they believed was their fair “share” of spoils—a materially divisible slice of the American state that was due in proportion to political influence.Footnote 96 William Seward invoked this popular mercenary spirit as a fresh-faced Senator arriving in the capitol at the dawn of the Zachary Taylor Administration in 1849. “The world seems almost divided into two classes, both which are moving in the same direction,” Seward noted wryly: “those who are going to California in search of gold, and those going to Washington in quest of office.”Footnote 97 Dividing spoils at national conventions and through cabinet deliberations became a focal point of factional conflict during the Gilded Age, for example, between Republican Stalwarts and Half-Breeds in the 1880s.Footnote 98

Competition was fierce because some offices were highly valuable beyond modest fixed salaries. Dating from the colonial period, elected and appointed officials were often empowered to collect a variety of specialized fees, bounties, moieties, and gifts from the communities they governed as compensation for leadership.Footnote 99 Under these conditions, the “perquisites” of office, as they were called, became an acknowledged way to build a personal fortune. Positions like judicial, militia, and territorial offices on the frontier were part of the allure for White men to migrate westward, conquer Native territory, and profit by selling land title to other settlers.Footnote 100 Law enforcement, a quintessentially local function, was especially profitable. The Sheriff of San Francisco County in the 1850s was among the highest paid officers in the country, collecting in fees four times the president’s salary.Footnote 101 Beyond legal rates, policemen, jailers, and most officers tasked with implementation of health, building, lottery, or liquor codes, were known to accept monetary indulgences from criminal suspects, inmates, and businessmen.Footnote 102 The urban revolution that swelled populations between 1870 and 1920 created regional anchors of economic activity and powerful voting blocs who pressed for local control.Footnote 103 This “municipal pot of gold,” as Steve Erie called it, generated ample sources of partisan financing from a range of local emoluments.Footnote 104

Another allure was that personal finances were intimately mixed with public monies. It was common practice for state and county treasurers to accumulate private interest on taxpayer deposits. Elected officials, including treasurers and comptrollers, were often presidents, directors, or investors in banks that safeguarded public funds. Government revenues of all kinds were frequently embezzled as fonts of capital with which to speculate or pay personal debts.Footnote 105 Infamously, Andrew Jackson’s Collector of the Port of New York, Samuel Swartwout, diverted tariff revenues to purchase tens of thousands of acres of land in Mexican Texas in the 1830s. Swartwout then supported independence with financing and political support to make the investment pay. During 9 years in office, he embezzled a fortune—somewhere between $1 and $2 million.Footnote 106 Scandal only erupted if the prospects of a speculative venture collapsed, as they did with Swartwout, and the embarrassed officer’s personal finances were too shattered to return equivalent funds, thereby exposing a conspicuous deficit.

Even more lucrative than fees or bounties were indirect officeholding emoluments tied to developmentalist economic agendas. “Spatial emoluments” were a major benefit tied to the associational state’s flexible capacity. Voluntarism was leveraged to achieve important public goals, as scholars from Theda Skocpol to Brian Balogh to Elisabeth Clemens have noted.Footnote 107 Somehow, far less has been said about the flip side of private benevolence. The political generation of local real estate markets through place-making public works became a common way to achieve public ends. It was also a reliable conduit for state and local patrons to enrich themselves, going all the way back to George Washington’s private land speculations around the nation’s capital and public land sales in the old northwest territories.Footnote 108

Civic boosters such as Jesup Scott of Toledo, Ohio, or Le Baron Bradford Prince of Santa Fe, New Mexico, would enhance the value of private land investments by building governing institutions, donating land, chartering schools, and establishing churches.Footnote 109 Internal improvements like canals, harbors, turnpikes, and later, railroads, helped to build regional and then national markets in land, natural resources, and agricultural commodities.Footnote 110 Tammany Hall employed precisely the same strategies as Scott and Prince—leveraging public works to boost private land values and, thus, to monetize associational networks. But Tammany did so in Manhattan, the most expensive real estate market in the country after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825.Footnote 111 At the height of influence during the Gilded Age, when Tammany patronized a wide range of religious and benevolent groups, it was just as much a real estate brokerage firm as a political organization.Footnote 112

6. Party oeconomics

The institutional setting from which party organization emerged helps to explain patrimonial features of the old American state. We know that mass politics drove party bureaucratization. Under competitive pressures of electoral mobilization, party bosses and committees superseded local notables and elite reputational networks, culminating, by 1896, in national structures that were increasingly centralized.Footnote 113 But, more specifically, democratization emerged out of a patrimonial enclave in household politics that continued to shape party development. From George Washington to Frederick Douglass, nearly every public figure of consequence practiced politics as an extension of the household favoring kin and close friends.Footnote 114

It was not quite that politics was suffused with nepotism, but, rather, by ties of affective dependence. Before Amos Kendall could officially join the Jacksonian camp, for instance, he had to sever business with Henry Clay by settling his personal debts.Footnote 115 Personalism was an expression of household politics that never disappeared so much as it was transformed and absorbed by party institutions.Footnote 116 As the century progressed, household social ties became more abstract, bureaucratic, and, especially when it came to party politics, reliant on symbolic rituals of collective adherence.

By mid-century, kinship was no longer mere biological family or intimate friendship but also devotion to the “shrine of party”—the greater partisan imagined community.Footnote 117 Office hunters came to rely for the promotion of their claims upon party endorsements from local public meetings, county and state party committees, and, above all, the support of powerful political bosses. Claims of personal intimacy were still an important measure of political influence as late as the Gilded Age. In practice, however, the impersonal bureaucratization of party often strained those claims to friendship beyond credulity.Footnote 118

The gradual and uneven emergence of internal party markets for public office are a concrete example of how patrimonial discretion was stretched in new ways across the century. Mass mobilization required geographically and demographically expansive coalitions; yet there were simply too many patronage claims to adjudicate. And, because there was no single route to any appointment, officeseekers did whatever they could to first secure and then retain a position. To avoid removal from a long-held postmastership in Albany, New York, Solomon Van Rensselaer secured a private audience with President Andrew Jackson through the patrician Edward Livingston. At this meeting, Van Rensselaer bared his chest to reveal old wounds from the War of 1812, a tactic dramatic enough to win support from the former general at a moment when gentry incumbents were in peril.Footnote 119 Advantages of petitioning in person for a lucrative “situation” were simply too important to pass up, which remained an axiom of officeseekers throughout the century.Footnote 120 Yet, few people enjoyed the benefits of Van Rensselaer’s kind of personal access. Many of those trampling the White House lawn for a spot at the punchbowls celebrating Jackson’s first inauguration were office hunters little different than Van Rensselaer; the main difference was they failed to penetrate Jackson’s inner court.

The officeseeking crowd could manifest as unruly mobs, especially at moments of party alternation. When the Whigs finally came to power in 1841, William Henry Harrison arrived to find his first cabinet meeting jam packed with applicants descended from around the country. Harrison himself had also been a career beggar for offices.Footnote 121 A decade earlier, General Harrison had come to Washington because he felt “entitled to reward” at a time when “[m]y coat was scarcely decent and my finances so low that I was not able to make carriage in the worst weather.”Footnote 122 Now that he was in position as the republic’s grand patriarch, President Harrison appealed in earnest for all officeseekers obstructing his cabinet meeting to vacate in the name of public business. The crowd refused, much to his dismay, “unless he would receive their papers and pledge himself to attend to them.” The president’s pockets, hat, and arms, and those of his attending marshal, were then loaded up with claims and testimonials, after which the two men “marched up stairs with as much as they could carry.”Footnote 123 Many of these valiant efforts by office hunters ended in vain. Shortly thereafter, Harrison died unexpectedly, leaving patronage matters to John Tyler. With only the most tenuous connections to party regularity, Tyler moved decisions over patronage from Whigs to Representative Henry Wise of Virginia and his circle of proslavery friends.Footnote 124 Patrimonial job markets were vulnerable to even the most subtle partisan shifts.

Crowds with similar hopes stalked the doors of governors, mayors, port collectors, and other executives around the country with the power of appointment. Where competition was fierce for the most lucrative posts, bidding wars opened up party markets for venal office, yet another lineage of the medieval European state.Footnote 125 Distinctive approaches cemented a divide between competition for office by merit of party service, for Democrats, or by moral and social desert, for Whig-Republicans.

The Democratic Party’s approach was anathema to Whigs because “it holds out the idea that all men are qualified for all offices, and decries the value of experience, faithfulness and skill.”Footnote 126 Whigs, Republicans, and later elite Progressive Era reformers thus favored the refining of officeholders through appointments to boards, commissions, and public corporations that were based upon social credentials, technical expertise, and propertyholding. By contrast, to Democrats the spoils of office were viewed as a just reward for competition between Jeffersonian equals (meaning, White men) that was inherent to party regularity.Footnote 127 They tended to be wary of publicly chartered corporations, the Second National Bank of the United States, most famously, but also state-chartered canal companies and railroads that placed a mix of public and private capital into the hands of political appointees. Democrats preferred elected offices, for example, in clashes over urban governance with state legislatures about home rule that increasingly arose after the 1870s.

The extent to which internal party markets were stable and coherent, however, depended upon the ability of a local leader who could accept clients’ money and credibly guarantee what was promised—no easy feat. Because of men’s ambitions and the fragility of coalition politics, party markets were often made and unmade, with a good deal of uncertainty baked into the process. Here is at least one measure: the burden of political assessments (party taxes) and the speculative cost of nominations grew so onerous that, by the Gilded Age, one strategy of civil service reformers was to air the complaints of officeholders’ wives and children about the household burdens of paying for office.Footnote 128

The officeholding career of Kate Brown offers a vantage to understand how the extended party household was adapted to periodic advances in democratization. During the heyday of Reconstruction, Brown was a Black appointee to the U.S. Senate who worked as an attendant in the “ladies’ retiring room.” Thousands of women entered the federal workforce during the Civil War for the first time in American history.Footnote 129 The Union’s crisis suddenly opened the prospect of property-bearing citizenship for freedmen and freedwomen that republican officeholding had always implied for White men. As the historian Kate Masur has shown, Kate Brown held her Senate post for 20 years, accumulating a modest amount of property by carefully saving and investing her salary.Footnote 130 Those resources enabled her to become a benefactor of two churches and a host of civic associations in the local Black community. When she was physically assaulted and thrown off a train in 1868 for riding in the ladies’ car, at a critical juncture in congressional debates over racial discrimination, Brown rallied support from Republican Senators like Charles Sumner of Massachusetts. She pressed her civil right to public transportation in the courts and won a landmark case, including $1,500 in damages.Footnote 131

Kate Brown offers an illuminating example of both continuity and innovation in clientelism. By nineteenth-century standards, her actions were part of a tradition in which civic stature and moral leadership was directly linked to officeholding political economy. To be sure, Kate Brown led an uncommon life.Footnote 132 Formerly enslaved, she divorced an abusive husband in the 1860s at a time when that was rare. She successfully sued a railroad company over a violation of her civil rights. And she became a crucial ally for Black officeseekers during Reconstruction, often forwarding their applications to U.S. Senators that she knew for consideration.Footnote 133 In this way, Brown’s case also shows the impact of political change. Extending the responsibilities and benefits of officeholding to previously dependent groups, even minor offices, signaled the potential to reorder socially inherited inequality. During the Civil War and Reconstruction, Democrats argued forcefully that the Republican Party’s program would unravel social order itself.Footnote 134 Kate Brown represented not only the abolition of slavery and the prospect of equal rights, but also a challenge, more fundamentally, when racialized and gendered “dependents” stepped out of the republican penumbra to stand as political actors in their own right.

Battles over the meaning and substance of citizenship before the modern era were often contested upon a ‘familiar’ terrain of who ought to rightfully take their place at the forefront of political representation. Importantly, the history of women’s officeholding long predates the Nineteenth Amendment and, in notable cases, even state-level suffrage rights.Footnote 135 White women appointees to the Indian Bureau during the Gilded Age like Florence Etheridge and Flora Warren leveraged maternalistic guardianship over Native peoples into potent examples of civic authority for the women’s suffrage movement. By contrast, some Native employees like Gertrude Bonnin, a Sioux woman, became staunch defenders of tribal sovereignty and cultural autonomy.Footnote 136

The same link between officeholding and rights was dramatically illustrated by strident opposition from White southern Democrats to Black postmasters, port collectors, and other federal employees who survived in the early Jim Crow South by navigating Republican Party convention politics.Footnote 137 The 1903 nomination of William D. Crum, a Black medical doctor, to lead the Charleston custom house was filibustered for years by “Pitchfork” Ben Tillman, an avowed White supremacist. Crum framed his Senate confirmation struggle as a larger question of where the penumbra of representation fell nearly a half-century after emancipation: “[I]t is up to the people of this country to say once and for all, whether we are citizens or not.”Footnote 138

7. The Republic’s classical age

America erected a mixed state during the Long Nineteenth Century that was at once both patrimonial and capitalist. Between the late colonial period and the New Deal, governance under the old republic grew out of the confluence of customary officeholding practices and changing social property relations. By the mid-nineteenth century, feudal lineages of dependence had fused with the kind of profit-seeking political exchanges typical of a more freewheeling capitalist economy. This historical co-development embedded layers of hierarchy and inequality within the American polity, largely by drawing boundaries of social difference around the extended party household. The lengthy penumbra cast by the American state over racial and gendered dependents throughout this long period was constitutive of political clientelism, including its party oeconomics. Political developments like the rise of mass patronage markets were linked not only to electoral competition and officeholding political economy but also to claims by excluded groups that sought to occupy legitimate space within the public sphere.

The social embeddedness of the patrimonial state offers perspective on why political incorporation proved so frustrated when it came to expanding civic rights to groups like Black Americans, women, and Native peoples. It also explains why so many efforts to depoliticize the civil service were frustrated, even after the passage of landmark merit-based laws like the Pendleton Act of 1883 and the election of successive waves of Progressive Era reformers to municipal government. Officeholding was not simply about winning elections or securing control over policy. It was a far more expansive struggle for social power within the household state.

Under the Old Republic, representation was based upon an intimate political economy that related to both civic status and access to economic capital. A White male head of household was empowered to broker an official, public relationship with a host of dependents even as those dynamics were bureaucratized by the mass party. People stuck on the outer reaches of the republican penumbra during the nineteenth century did not typically experience civic equality but rather patrimonial rule. When democratizing currents lifted excluded groups out of this penumbra, the result was often the creation of yet another layer of patron and client relationships.Footnote 139 In this way, the old American state was something to be negotiated on personal terms.

A “new” democratic state that prioritized a capacious demos over private inequalities was born in fits and starts between the Civil War and the Great Depression.Footnote 140 From an officeholding standpoint, however, only the New Deal signified a break with this longstanding clientelistic mode of governing. The political resolution to the Great Depression of the 1930s reorganized political economy to match interest group liberalism with the twentieth century’s bureaucratization of corporate capital. The New Deal Order established new institutional venues, mechanisms of administrative rule, and legal innovations that recognized abstractions in group interest and the separation of public from private property, even as it carved out exceptions for racial authoritarianism in the Jim Crow south.Footnote 141 Hatch Act (1939) prohibitions on electioneering, and the management of public property by professionally trained technocrats, ensured the trend in modern statecraft was to strip away traditional forms of personal and party discretion in favor of impersonal, programmatic goals. Most significant in curtailing an intimate patrimonial household economy was labors’ right to collective bargaining in the 1930s, which brought rule of law to the workplace, and the erection of a Civil Rights State after the 1960s, which challenged private forms of discrimination. The party’s old sources of patrimony shrank considerably but unevenly as the sphere of public regulation grew and “dislodged governance previously in place.”Footnote 142

Let us not forget, however, that clientelism proved resilient and adaptable to varied historical conditions over a remarkably long era. Explaining the persistence of the ancien régime in Europe up to World War I, Arno Mayer wrote of “a marked tendency to neglect or underplay, and to disvalue, the endurance of old forces and ideas and their cunning genius for assimilating, delaying, neutralizing, and subduing capitalism modernization.”Footnote 143 Patron–client relationships supplied the old American state with a deep reservoir of flexible resources, popular legitimacy, and powers over particularistic beneficence. But this system also created the kind of polity where a Federalist postmaster, on a whim, could unilaterally censor or even block the mail of Jeffersonian rivals. Defying a party leader even just once during the age of mass politics could end a promising public career or temporarily strip a community of influence. Government was for-profit, if not by express design, then at least by established tradition. Political behavior had every incentive to take on a mercenary character because officeholding emoluments were subject to party competition for nominations and appointments. Plainly, the extended household state harbored all the vices of patrimonial administration.

Rethinking the classical age of republicanism raises a number of questions for the study of American political development. Did patrimonial enclaves simply disappear with the rise of the modern administrative state and the gradual expansion of rights to formerly excluded groups? Or did the older representational inequalities of “belated feudalism” become smuggled under the patina of shiny modernist edifices, passing hidden into the twentieth century state and even today? We know that the presidency generates a kind of “political time” that structures political institutions and historical behavior.Footnote 144 To what extent do the honors and emoluments of republican officeholding, and its reciprocal social hierarchies, foster recurring patterns of clientelism? Will patrimonial governance revive if access to citizenship is again circumscribed by race and gender, if the Roberts Court strikes down modern agency rulemaking, if future presidents lift civil service protections, and if the Administrative Procedure Act and the Hatch Act are ignored?Footnote 145 Richard Croker’s Irish castle may cast a lengthier shadow than many scholars have been willing to acknowledge.