Recent longitudinal studies highlight that adults increase body weight gradually through middle age, with an average annual weight gain of approximately 0·5 kg( Reference Mozaffarian, Hao and Rimm 1 , Reference Peeters, Magliano and Backholer 2 ). This accumulation of body weight has resulted in an increased prevalence of obesity and its associated co-morbidities, as obesity incidence rates are now above 20 % in most Western countries and represent a major public health burden( Reference Swinburn, Sacks and Hall 3 ). As a result, interventions that can be safely applied at the population level to prevent long-term weight gain would have major benefits to public health. It has been suggested that gradual adult weight gain can be the result of only a small habitual positive energy balance of 209·2–418·4 kJ/d (50–100 kcal/d)( Reference Zhai, Wang and Wang 4 ). Consequently, an improved understanding of the hormonal and neuronal signals that control appetite regulation may facilitate the development of novel dietary strategies that supress energy intake and oppose a positive energy balance and long-term weight gain.

Epidemiological and experimental studies have consistently highlighted an inverse association between dietary fibre intake and body weight gain( Reference Ludwig, Pereira and Kroenke 5 – Reference Du, van der and Boshuizen 7 ). Furthermore, an increased intake of dietary fibre has been associated with improved appetite regulation( Reference Liu, Willett and Manson 8 ), thus making high-fibre diets an attractive strategy to reduce obesity levels. The current definition of dietary fibre( Reference Cummings, Mann and Nishida 9 ) encompasses a diverse range of compounds with different chemical structures that influence their physiological effects. As a result, it has been proposed that dietary fibre can increase levels of satiation (the process that leads to the termination of eating) and satiety (the process that leads to inhibition of further eating after a meal has finished) by numerous mechanisms, depending on the natural properties of the ingested fibre( Reference Slavin 10 ). Evidence suggests that the fermentable component of some dietary fibres may be important in promoting appetite regulatory effects and improvements in weight management( Reference Wanders, van den Borne and de Graaf 11 ). Current Western diets contain energy-dense foods that are generally low in fibre (10–20 g/d) and high in sugars and fats( Reference Whitton, Nicholson and Roberts 12 ). This is in marked contrast to the Palaeolithic diet, which contained >100 g/d dietary fibre, to which the human gastrointestinal (GI) system has evolved over several millennia( Reference Eaton 13 ). This ancestral diet was rich in indigestible plant material, which would have contained a large fermentable fibre component, and it has been suggested that the modern low-fibre diet fails to stimulate many satiation and satiety signals originating from the GI tract( Reference Frost, Walton and Swann 14 ). Dietary fibre passes through the small intestine unaffected by digestive enzymes, and upon reaching the colon, anaerobic bacteria are able to degrade some of these dietary fibres via a fermentation process that yields energy for the resident micro-organisms. The fermentability of dietary fibre varies, with resistant starches, NSP and non-digestible oligosaccharides being principal fermented substrates( Reference Topping and Clifton 15 ). It has been estimated that the human gut microbiota consists of 1013–1014 micro-organisms and is composed of approximately 1000 different species of bacteria, which belong to three principal phyla: Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria ( Reference Gill, Pop and Deboy 16 , Reference Qin, Li and Raes 17 ). The main end-products of microbial fermentation are SCFA, heat and gases (CO2, H2 and CH4)( Reference Macfarlane and Macfarlane 18 ). SCFA are classified as carboxylic acids that contain less than six carbon atoms. The most abundant (about 95 %) SCFA present in the human colon lumen are acetate (C2), propionate (C3) and butyrate (C4), in the approximate molar ratio 60 : 20 : 20( Reference Cummings, Pomare and Branch 19 ). The precise production of SCFA is difficult to measure in human subjects due to the inaccessibility of the colonic lumen. Furthermore, the formation of different SCFA can vary considerably between individuals due to large differences in gut microbial composition and activity( Reference Cummings, Pomare and Branch 19 ). Bacterial species that belong to the Bacteroidetes phylum mainly produce acetate and propionate, whereas the Firmicutes phylum primarily produces butyrate( Reference Macfarlane and Macfarlane 18 ). An investigation that measured SCFA directly from the human gut lumen reports that the highest concentrations are present in the proximal colon (about 120 mm/kg luminal contents) and these levels decrease distally through the colon( Reference Cummings, Pomare and Branch 19 ), revealing that SCFA are rapidly absorbed across the apical and basolateral membranes of colonocytes. It is estimated that fermentation of dietary fibre can yield 400–600 mm SCFA/d, which is equivalent to about 5–10 % of human energy requirements( Reference Royall, Wolever and Jeejeebhoy 20 ) and, furthermore, it has been consistently demonstrated in animals( Reference Levrat, Remesy and Demigne 21 – Reference Arora, Loo and Anastasovska 24 ) and human subjects( Reference Cummings, Beatty and Kingman 25 , Reference Jenkins, Vuksan and Kendall 26 ) that the amount of dietary fibre consumed has a considerable effect on the concentration of SCFA produced in the large bowel. The aim of the present review is to evaluate the possible mechanisms that may explain how an elevated colonic production of SCFA could supress short-term appetite responses and energy intake.

Central nervous system control of appetite and energy intake

The hypothalamus and the brainstem are the main central nervous system regions responsible for the regulation of appetite and energy intake. These brain areas integrate the complex peripheral hormonal and neuronal signals that represent the current physiological state of the body( Reference Murphy and Bloom 27 , Reference Hussain and Bloom 28 ). The arcuate nucleus (ARC) within the hypothalamus senses hormones secreted into the peripheral circulation through a semipermeable blood–brain barrier. This nucleus contains two populations of neurons: (1) the orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) neuropeptide Y and agouti-related peptide and (2) the anorexigenic (appetite-suppressing) pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) and cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript. Within the brainstem, the nucleus of the solitary tract integrates neural signals derived from stimulation of vagal afferents in the gut and other visceral tissues in response to chemical, mechanical and hormonal stimuli. There are extensive reciprocal connections between the hypothalamus and the brainstem and appetite responses and energy intake are coordinated on the basis of the hormonal and neural signals received by both brain regions( Reference Murphy and Bloom 27 , Reference Hussain and Bloom 28 ).

SCFA receptors and anorectic gut hormone release

In 2003, it was demonstrated that SCFA act as ligands for the previously orphaned G-protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43( Reference Brown, Goldsworthy and Barnes 29 – Reference Nilsson, Kotarsky and Owman 31 ). These receptors have since been renamed free fatty acid receptor (FFAR) 3 and FFAR2, respectively. As G-protein coupled receptors, FFAR2 and FFAR3 are linked to heterotrimeric G-proteins attached to the cytoplasmic side of the receptor and stimulation of individual G-proteins trigger different cellular responses through the activation of specific secondary messenger cascades. FFAR2 couples to both Gi/o- (pertussis toxin-sensitive) and Gq-proteins (pertussis toxin-insensitive), whereas FFAR3 couples only to Gi/o-proteins( Reference Brown, Goldsworthy and Barnes 29 , Reference Le Poul, Loison and Struyf 30 ). Both FFAR2 and FFAR3 are activated by physiological concentrations of SCFA, although a preference of FFAR2 for acetate and propionate and of FFAR3 for propionate and butyrate has been reported( Reference Brown, Goldsworthy and Barnes 29 – Reference Nilsson, Kotarsky and Owman 31 ). These receptors have been shown to be expressed not only in the gut epithelium( Reference Karaki, Tazoe and Hayashi 32 , Reference Tazoe, Otomo and Karaki 33 ) where SCFA are produced and are at their highest concentrations, but also at multiple tissue sites, including adipose tissue( Reference Hong, Nishimura and Hishikawa 34 – Reference Kimura, Ozawa and Inoue 36 ), immune cells( Reference Brown, Goldsworthy and Barnes 29 ), skeletal muscle( Reference Nilsson, Kotarsky and Owman 31 ) and within the peripheral nervous system( Reference Kimura, Inoue and Maeda 37 , Reference De Vadder, Kovatcheva-Datchary and Goncalves 38 ). A possible role for these receptors in energy intake regulation emerged with the identification that FFAR2 and FFAR3 are present on colonic endocrine L-cells( Reference Karaki, Tazoe and Hayashi 32 , Reference Tazoe, Otomo and Karaki 33 ). The L-cell is found at its highest density in the colonic epithelium( Reference Eissele, Goke and Willemer 39 ) and secretes the anorexigenic hormones peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1( Reference Murphy and Bloom 27 ).

PYY is released into the circulation after food intake, with levels rising to a plateau after 1–2 h and remaining elevated for up to 6 h( Reference Adrian, Ferri and Bacarese-Hamilton 40 ). Intravenous infusion of PYY to both lean and obese human subjects has been demonstrated to reduce energy intake( Reference Batterham, Cowley and Small 41 , Reference Batterham, Cohen and Ellis 42 ), and this anorexigenic effect is thought be exerted via neuropeptide Y inhibition and POMC activation in the hypothalamic ARC( Reference Batterham, Cowley and Small 41 , Reference Abbott, Small and Kennedy 43 ). Peripheral vagal afferents are also involved in the appetite-suppressive action of PYY, as the hormone has been shown to stimulate the activity of gastric vagal nerves and vagotomy was reported to abolish the effect of PYY on feeding responses( Reference Abbott, Monteiro and Small 44 , Reference Koda, Date and Murakami 45 ).

GLP-1 is primarily recognised as an incretin, but it also fulfils several criteria in order to be considered a satiety signal. Circulating levels of GLP-1 rise following a meal in proportion to energy intake and are low in the fasted state( Reference Herrmann, Goke and Richter 46 ). Furthermore, across a range of studies intravenous infusion of GLP-1 has been demonstrated to acutely reduce food intake in human subjects( Reference Verdich, Flint and Gutzwiller 47 ). GLP-1 receptors are expressed in many regions throughout the hypothalamus, with high levels in the ARC( Reference Goke, Larsen and Mikkelsen 48 ). Abolishing ARC neuronal signalling eliminates the inhibitory effect of GLP-1 on food intake and appetite( Reference Tang-Christensen, Vrang and Larsen 49 ). Similar to PYY, the action of circulating GLP-1 on appetite-regulatory circuits in the brain may in part be via the stimulation of peripheral vagal afferents( Reference Abbott, Monteiro and Small 44 ).

Due to the potent effects of PYY and GLP-1 on feeding behaviour, interventions that increase the circulating levels of these gut hormones are the target of many anti-obesity strategies. The discovery that FFAR2 and FFAR3 are co-localised with L-cells in the colon has led to the suggestion that activation of these receptors by SCFA ligands would facilitate PYY and GLP-1 release. Investigations using rodent primary colonic cultures have consistently shown that SCFA stimulate the release of PYY and GLP-1 from colonic L-cells( Reference Longo, Ballantyne and Savoca 50 – Reference Tolhurst, Heffron and Lam 53 ). Tolhurst et al. ( Reference Tolhurst, Heffron and Lam 53 ) observed that SCFA activation stimulated GLP-1 secretion from wild-type murine L-cells and these effects were significantly attenuated in FFAR2 knock-out (−/−) and FFAR3−/− cells. However, in vivo, only FFAR2−/−, but not FFAR3−/− mice, had significantly reduced circulating levels of GLP-1. It was found that FFAR2 enhances GLP-1 secretion by triggering an intracellular calcium response in the L-cell via the specific coupling of FFAR2 to Gq-proteins. It was therefore suggested that the blunted response to SCFA observed in FFAR3−/− colonic cultures may be related to the reduced expression of FFAR2 observed in FFAR3−/− mice( Reference Zaibi, Stocker and O'Dowd 35 ). A recent investigation supports a primary role of FFAR2 in stimulating gut hormone release( Reference Psichas, Sleeth and Murphy 54 ). It was found that the SCFA propionate stimulates the secretion of both PYY and GLP-1 from wild-type primary murine colonic crypt cultures and this effect was significantly reduced in FFAR2−/− mice cultures. In addition, an in vivo model demonstrated that intra-colonic administration of propionate stimulates the simultaneous release of both GLP-1 and PYY in rodents and that this stimulatory effect was abolished in FFAR2−/− animals. These studies would therefore suggest that increasing the intake of fermentable dietary fibres and colonic production of SCFA would stimulate PYY and GLP-1 release. Indeed, a number of studies have reported that animals fed high doses of fermentable fibres have increased endogenous secretions of PYY and GLP-1( Reference Cani, Dewever and Delzenne 55 – Reference Zhou, Martin and Tulley 59 ), as well as an increased number of colonic L-cells( Reference Cani, Hoste and Guiot 60 ). In human subjects, it has been shown that adding 24 g of the fermentable fibre oligofructose to a test meal significantly increased GLP-1 levels in the postprandial period( Reference Tarini and Wolever 61 ). This finding is supported by an investigation that revealed that feeding 16 g oligofructose/d for 2 weeks significantly lowered subjective hunger ratings, which was associated with increased PYY and GLP-1 release during a test meal( Reference Cani, Lecourt and Dewulf 62 ). Furthermore, in a longer-term investigation, overweight volunteers were given 21 g oligofructose/d or a placebo for 12 weeks and the fermentable fibre intervention group experienced significant weight loss compared with the placebo group, which was associated with enhanced PYY release and reduced self-reported energy intake during the supplementation period( Reference Parnell and Reimer 63 ). Recent reports have suggested that the amount of fermentable fibre consumed in the diet is critical to observe an effect on gut hormone release, as it was found that the supplementation of 16 g oligofructose/d, but not 10 g/d, for 13 d stimulated postprandial PYY and GLP-1 release( Reference Verhoef, Meyer and Westerterp 64 ). This would suggest that high daily intakes of fermentable fibres may be needed to produce the colonic concentrations of SCFA required to modulate PYY and GLP-1 release. This is supported by a recent dose-escalation study in healthy human participants completing a 5-week supplementation period where the daily intake of oligofructose increased from 15, 25, 35, 45, 55 g/d each week and it was found that intake of fermentable fibre exceeding 35 g/d was needed to elevate post-prandial PYY release( Reference Pedersen, Lefevre and Peters 65 ). In summary, available evidence suggests that SCFA are capable of stimulating the anorectic gut hormones PYY and GLP-1 from colonic L-cells, primarily via the activation of FFAR2. Consequently, with a sufficiently high dietary intake, fermentable fibres can elevate anorectic gut hormone profiles, through an increased colonic production of SCFA.

SCFA and digestive tract motility

The GI tract contains mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors that relay information to the central nervous system via vagal afferents, which contribute to the regulation of satiation and satiety( Reference Hussain and Bloom 28 ). It has been proposed that slowing the rate at which ingested food passes through the GI tract prolongs stimulation of these chemo- and mechanoreceptors, which in turn extends satiety following food intake( Reference Hellstrom and Naslund 66 , Reference Janssen, Vanden Berghe and Verschueren 67 ). For example, numerous studies have reported that delaying the gastric emptying of ingested food is associated with short-term effects on appetite and satiety measures( Reference Di Lorenzo, Williams and Hajnal 68 , Reference Santangelo, Peracchi and Conte 69 ). The direct effect of luminal SCFA on colonic motility has been studied using in vitro and in vivo models. Squires et al. ( Reference Squires, Rumsey and Edwards 70 ) reported that large concentrations of SCFA decreased colonic contractile activity when infused in an isolated rat colon. However, in vivo studies performed in human subjects have failed to indicate that SCFA directly modulate colonic motility. Recently, it has been reported that in twenty healthy human volunteers intra-colonic infusion of a SCFA mixture had no direct effects on colonic motor activity, measured with perfused catheters and an electronic barostat( Reference Jouet, Moussata and Duboc 71 ), supporting a previous observation involving two human subjects( Reference Kamath, Phillips and O'Connor 72 ). Nevertheless, SCFA may modulate motility of the upper digestive tract through the release of PYY and GLP-1. Cherbut et al. ( Reference Cherbut, Ferrier and Roze 51 ) observed that intraluminal infusion of SCFA into the rat colon significantly slowed gut transit rate. It was reported that the colonic infusion of SCFA released PYY in the peripheral circulation, suggesting that PYY could mediate the inhibitory effect of SCFA on gut motility. This hypothesis was supported by the finding that when colonic SCFA were administered following the immunoneutralisation of circulating PYY the effect of SCFA on gut transit rates was abolished. PYY is one of the hormones considered to mediate the ‘ileal brake reflex’, and studies have shown PYY to inhibit gastric emptying( Reference Pappas, Debas and Chang 73 , Reference Lin, Zhao and Wang 74 ). In addition, it has been found that elevating circulating levels of GLP-1 can also slow rates of gastric emptying( Reference Naslund, Gutniak and Skogar 75 , Reference Edholm, Degerblad and Gryback 76 ). Consequently, SCFA-stimulated release of PYY and GLP-1 from colonic L-cells may be capable of modifying appetite responses by delaying the gastric emptying of ingested foods and prolonging the stimulation of mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors in the GI tract.

Hepatic metabolism of propionate

As previously mentioned, the largest concentrations of SCFA are found in the proximal colon, where SCFA are rapidly absorbed by colonocytes. Measurements in isolated colonocytes have shown that the majority of the energy demands of colonocytes (about 70 %) are derived from oxidation of SCFA( Reference Clausen and Mortensen 77 ). SCFA that are not metabolised by colonocytes are released from the gut via the hepatic and portal vein system and measurements in human subjects have found that the molar fractions of acetate, propionate and butyrate change from approximately 60 : 20 : 20 in the colonic lumen to 70 : 20 : 10 in the portal vein( Reference Cummings, Pomare and Branch 19 ), indicative of the preferential use of butyrate by mammalian colonocytes as an energy source( Reference Clausen and Mortensen 77 , Reference Ardawi and Newsholme 78 ). SCFA that are not metabolised by the liver then enter the peripheral circulation, where the approximate molar fraction is changed to 90 : 5 : 5 for acetate, propionate and butyrate, respectively( Reference Cummings, Pomare and Branch 19 ). This demonstrates that the liver takes up a considerable amount of propionate from the circulation. Indeed, it has been estimated that about 90 % of propionate in the portal vein is extracted by the liver( Reference Peters, Pomare and Fisher 79 ). Propionate is a known precursor for hepatic gluconeogenesis( Reference Al-Lahham, Peppelenbosch and Roelofsen 80 ), where propionate is rapidly converted to propionyl-CoA and enters the TCA-cycle at the level of succinyl-CoA. This leads to an elevation in the levels of oxaloacetate, which is converted to glucose. Data obtained from animal models suggest that elevating hepatic energy status can modulate appetite and feeding behaviour through the stimulation of hepatic vagal afferents that signal to the nucleus of the solitary tract within the brainstem( Reference Allen, Bradford and Oba 81 ). Evidence for a role of hepatic propionate metabolism as a satiety signal comes primarily from ruminant studies, as it has been extensively reported that portal infusions of propionate depress energy intake in sheep and cows( Reference Elliot, Symonds and Pike 82 – Reference Leuvenink, Bleumer and Bongers 84 ). Furthermore, these hypophagic effects of elevating exogenous propionate in the portal vein are abolished with hepatic vagotomy or total liver denervation( Reference Anil and Forbes 85 , Reference Anil and Forbes 86 ). However, caution must be taken when considering ruminants as models to study appetite regulation in human subjects, as marked differences in energy utilisation exist between species. Ruminants must synthesise their entire glucose requirements via hepatic gluconeogenesis and exogenous propionate accounts for approximately 80 % of endogenous glucose production( Reference Allen, Bradford and Harvatine 87 ). It is therefore unsurprising that, as a major energy substrate, propionate availability provides such a potent satiety signal in ruminant species. While much less is known about the effect of propionate on glucose production in man, the vast majority of exogenous propionate is metabolised by the liver and a recent investigation using an innovative labelling strategy, in combination with localised in vivo 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy, reported that elevating exogenous propionate supply to the human liver increased hepatic glucose production by 30 %( Reference Befroy, Perry and Jain 88 ). As a key anabolic organ, which is estimated to contribute 20 % of resting energy expenditure in human subjects( Reference Blundell, Caudwell and Gibbons 89 ), it is plausible that substantial changes in hepatic glucose production and storage could be sensed centrally to regulate feeding behaviour. An interesting area of future research would determine how increasing the concentrations of propionate produced in the human colon would alter hepatic intracellular signalling pathways related to energy status, and whether these changes to hepatic metabolic processes provide an anorectic neural signal to appetite-regulatory regions of the brain.

SCFA and leptin secretion

SCFA that do not undergo hepatic metabolism enter the peripheral circulation, and concentrations in human peripheral blood of 170, 4 and 8 μmol/l have been reported for acetate, propionate and butyrate, respectively( Reference Bloemen, Venema and van de Poll 90 ). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated in human studies that elevating the fermentable fibre component of the diet raises SCFA levels in the peripheral blood( Reference Tarini and Wolever 61 , Reference Ferchaud-Roucher, Pouteau and Piloquet 91 – Reference Nilsson, Ostman and Knudsen 93 ), particularly concentrations of acetate. Circulating SCFA have been shown to interact with different peripheral organ and tissue sites. In particular, it has been demonstrated that SCFA have a major regulatory role in adipocyte function and metabolism( Reference Hong, Nishimura and Hishikawa 34 , Reference Kimura, Ozawa and Inoue 36 , Reference Ge, Li and Weiszmann 94 ) and are reported to stimulate leptin secretion( Reference Zaibi, Stocker and O'Dowd 35 , Reference Xiong, Miyamoto and Shibata 95 ). Circulating levels of leptin are proportional to fat mass and can cross the blood–brain barrier to induce an anorectic effect via the ARC, where both neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide and POMC/cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript neurons express leptin receptors( Reference Baskin, Breininger and Schwartz 96 ). Leptin inhibits neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide neurons and activates POMC/cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript neurons( Reference Sahu 97 ), resulting in reduced energy intake. Leptin-deficient mice have been shown to exhibit hyperphagia and obesity, which can be reversed by leptin administration( Reference Halaas, Gajiwala and Maffei 98 ). In 2004, Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Miyamoto and Shibata 95 reported that FFAR3 was expressed in adipocytes and that SCFA could stimulate leptin expression in both a mouse adipocyte cell line and mouse adipose tissue in primary culture. Furthermore, it was found in vivo that elevating circulating levels of propionate increased leptin levels in mice. Nevertheless, not all researchers have been able to detect FFAR3 in different adipose tissue sites( Reference Hong, Nishimura and Hishikawa 34 , Reference Kimura, Ozawa and Inoue 36 , Reference Kimura, Inoue and Maeda 37 ), thus the role of FFAR3 in adipose tissue function is currently a contentious topic. It has been consistently reported that FFAR2 is abundantly expressed in white adipose tissue( Reference Hong, Nishimura and Hishikawa 34 – Reference Kimura, Ozawa and Inoue 36 ) and suggested that FFAR2 may be responsible for stimulating leptin release from adipocytes. It was found that leptin secretion from wild-type adipocytes was increased by acetate, yet butyrate had no significant effect( Reference Zaibi, Stocker and O'Dowd 35 ). Owing to the different activation potencies of FFAR2 and FFAR3 to acetate( Reference Brown, Goldsworthy and Barnes 29 , Reference Le Poul, Loison and Struyf 30 ), this would imply that FFAR2 is responsible for triggering leptin secretion. Furthermore, leptin secretion from FFAR2−/− mice adipocytes was lower compared with wild-types. While acetate was also found not to secrete leptin from FFAR3−/− mice adipocytes, this was suggested to be due to a reduced expression of FFAR2 in these cells rather than the abolishment of FFAR3 signalling. Finally, it has been demonstrated that the effects of FFAR2 on leptin release are due to Gi/o-protein signalling, rather than a Gq-protein-mediated mechanism, as leptin secretion by SCFA is prevented in the presence of pertussis-toxin, which inactivates Gi/o signal transduction( Reference Zaibi, Stocker and O'Dowd 35 , Reference Al-Lahham, Roelofsen and Priebe 99 ). In summary, studies indicate that circulating SCFA, particularly acetate and propionate, can promote leptin secretion from adipocytes via activation of FFAR2, thus providing an anorectic signal to appetite-regulatory neurons in the hypothalamic ARC.

Direct central effects of acetate on hypothalamic control of appetite

As previously stated, acetate is the most abundant end product of colonic fermentation of dietary fibre and circulates at considerably greater concentration compared with propionate and butyrate. There is evidence to suggest that acetate can travel across the blood–brain barrier into the central nervous system( Reference Song, Nielson and Banks 100 ), raising the possibility that SCFA may have a direct effect on central appetite regulation. Using an intravenous and colonic infusion of 11C-acetate in mice and in vivo positron emission tomography-computed tomography scanning it was recently shown that up to 3 % of exogenous acetate was taken up by the brain in both the fed and fasted states( Reference Frost, Sleeth and Sahuri-Arisoylu 101 ). In particular, peripheral acetate was taken up by the hypothalamus in greater amounts than other brain tissues and it was found that within the hypothalamus acetate promotes an anorectic signal in the ARC, leading to increased POMC and reduced agouti-related peptide neuron expression. This investigation therefore provides a novel insight into the mechanism through which elevations in acetate production in the colon may mediate appetite suppression.

Conclusions

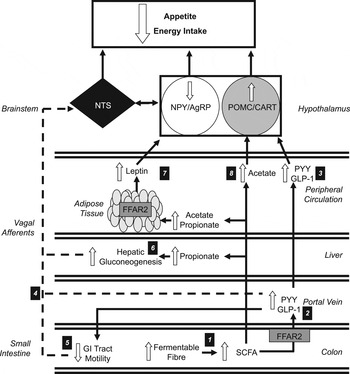

SCFA produced through the fermentation of dietary fibre in the colon have been shown to exert multiple effects on various organ and tissue sites. The present review has proposed that SCFA could stimulate numerous hormonal and neural signals that would cumulatively exert a potent anorectic effect. Many of these possible mechanisms (summarised in Fig. 1) would be strengthened with additional data from human studies, as the majority of the current available evidence to support a role of SCFA in appetite-regulation has been obtained from animal models, where direct translation into human subjects may be limited. Nevertheless, targeting the mechanisms through which SCFA suppress appetite through the development of novel dietary interventions that augment colonic SCFA production may be an effective strategy to improve appetite regulation and long-term weight management.

Fig. 1. Increasing the colonic production of SCFA stimulates multiple hormonal and neural mechanisms that suppress appetite and energy intake. (1) Increasing the intake of dietary fibre increases the amount of fermentable substrate reaching the colon, which is fermented by resident microbiota elevating the production of SCFA. (2) SCFA stimulate the release of peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY) and glucagon-like-peptide-1 (GLP-1) via the activation of free fatty acid receptor 2 (FFAR2) on colonic L-cells. (3) Within the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, peripheral PYY and GLP-1 increases the activity of the appetite-suppressing pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC)/ cocaine and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) neurons and inhibits appetite-stimulating neuropeptide Y (NPY)/agouti-related peoptide (AgRP) neurons. (4) Increased circulatory PYY and GLP-1 would modulate central appetite regulation via the stimulation of peripheral vagal afferents that are integrated in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) of the brainstem. (5) PYY and GLP-1 have also been shown to inhibit the motility of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This slows the gastric emptying of ingested foods and prolongs the stimulation of mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors in the GI tract that signal centrally via vagal afferents. (6) Increased concentrations of propionate in the portal vein would be taken up by the liver and stimulate hepatic gluconeogenesis. An increased hepatic energy status can modulate feeding behaviour via the stimulation of hepatic vagal nerve afferents. (7) Increasing acetate and propionate in the peripheral circulation stimulates leptin release from adipocytes via activation of FFAR2. Leptin inhibits NPY/AgRP neurons and activates POMC/CART neurons. (8) Acetate can cross the blood–brain barrier and increase POMC and reduce AgRP expression.

Financial Support

The Section of Investigative Medicine, Imperial College is funded by grants from the MRC, BBSRC, NIHR, an Integrative Mammalian Biology Capacity Building Award, an FP7-HEALTH- 2009- 241592 EuroCHIP grant and is supported by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre Funding Scheme. G. F. is supported by an NIHR senior investigator award. The work in SUERC is funded by the BBSRC and by a Scottish Government Strategic Partnership award in Food and Drink Science.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Authorship

E. S. C. wrote the paper and had primary responsibility for final content. D. J. M. and G. F. were involved in refining the paper.