The ‘Global Syndemic’, described as the triumvirate pandemics of undernutrition, obesity and climate change, represents the world’s greatest threat to human health(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender1). Multi-lens policies and programmes to synchronously tackle these major human issues are necessary(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender1–Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4). Addressing the relationships between planetary and human health, the EAT-Lancet Commission Report(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4) urges states to adopt a ‘Great Food Transformation’ programme. This transformation can only come about when all actors in the food system collaborate towards the shared goal of healthy and sustainable food systems(Reference Newell, Twena and Daley5). Changing consumers’ food-related behaviours to mitigate the rate of the planet’s environmental degradation has gained increasing support(Reference Newell, Twena and Daley5,6) . It has been suggested that the greatest impact will come from a shift towards a higher share of plant-based foods, particularly in those regions with high consumption of animal-based foods(6,Reference Fanzo, Bellows and Spiker7) . Within consumer behaviour, a ‘practice’ is defined as interconnected elements that represent ways of saying and doing(Reference Warde8). Practices include routines and rituals, the former including automatised behaviour whereas the latter are personally and culturally prescribed thoughtful behaviours elevated by profound meaning. However, changing current food lifestyles is problematic and while many health and sustainability problems originate from a complex food system(Reference Lang and Heasman9) understanding how consumers’ practice food and respond to changing narratives is key to developing appropriate policies and interventions(Reference O’Neill, Clear and Friday10).

Accelerating the shift towards the new hybrid of SuHe diets represents a significant challenge as deeply embedded beliefs, tied to emotions and practices, linked to factors such as tradition, knowledge and skills, tastes and preferences and personal and social value, represent change barriers(Reference Chan and Zlatevska11–Reference Steptoe, Pollard and Wardle17). In the acquisition, storage, preparation and consumption of food, consumers engage in a set of interwoven activities, representative of an integral part of one’s lifestyle, self and social identity, and household composition. Skilled navigation of this complex landscape is essential when promoting food choice change as such change demands adaptations to what is known, what is said and what is done about food(Reference Shove and Walker18), for instance, barriers such as tradition, time and habits have been shown to prevent widespread uptake of the Nordic diet(Reference Micheelsen, Holm and O’Doherty19). Transitioning to a sustainable diet requires systemic shifts in the way society functions(Reference Shove and Walker18) and the role of consumers as actors with agency within such a change process may have been underestimated(Reference Grin, Grin and Spaargaren20).

This review addresses the critical role of nutrition science in shaping dietary behaviour, and the challenges faced in changing a nutrition narrative to address sustainability, in addition to health. The associated implications for existing food practices are discussed. Furthermore, drawing on a broad social-psychological theoretical base, consideration is given to the role of strongly held traditional food beliefs in responses to communications/policy changes. Existing beliefs can impede the emergence of new food behaviour patterns and practices and can be expressed as resistance to new information. It is proposed that information that jars with existing belief systems creates dilemmas in the mind of the consumer that may create barriers to the transformation of dietary behaviour. Through this type of enquiry, sources of individual resistance or adoption can be understood to better inform public health policy and communication. Promising approaches and routes to integration of new beliefs into sustainable healthy dietary choices are also reflected on.

Food-based dietary guidelines and sustainable healthy dietary guidelines – a potential source of contention and confusion

Nutrition Science has historical precedence as a key discipline in the shaping of public understanding of the dynamic relationship between food and health. Over a century ago, nutritionists communicated links between diet and muscle performance(Reference Nungesser and Winter14) and diet and disease(Reference Fardet and Rock21). Dietary guidelines have been revised over the decades to reflect new scientific information and changing contexts(Reference Fardet and Rock21). Today, they represent recommendations formulated from scientific evidence, aimed at delivering optimal nutrition to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases, and translated for everyday use by the population. These guidelines also provide a framework for food policies and programmes(Reference Fernandez, Bertolo and Duncan22–Reference Herforth, Arimond and Álvarez-Sánchez24). However, consumer recognition and awareness of these guidelines are mixed(Reference Herforth, Arimond and Álvarez-Sánchez24–Reference Kebbe, Gao and Perez-Cornago26). This is compounded by poor understanding of and adherence to the guidelines in daily food decision-making(Reference Fernandez, Bertolo and Duncan22,Reference Brown, Timotijevic and Barnett27,Reference Vanderlee, McCrory and Hammond28) . A review(Reference Leme, Hou and Fisberg29) on adherence to such guidelines concludes that a large proportion of individuals were not meeting daily recommended intakes with overconsumption of meat and of discretionary food and underconsumption of vegetables common across most countries. While consumers are generally aware of guidelines for fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Scalvedi, Gennaro and Saba30), adherence continues to be low in the EU (EC, Eurostat 2019). All this suggests that basic education measures (in the form of guidelines) have limited impact on food purchases(Reference de Abreu, Guessous and Vaucher31) with reasons for poor compliance being many and varied. Consumers make up to 200 food decisions daily, both conscious and unconscious(Reference Wansink and Sobal32). Their choices are underpinned by their food-related capability, opportunity and motivation(Reference Michie, van Stralen and West33), are shaped by social and cultural norms and are influenced by the acquisition environment. Consequently, nutrition-related decisions are set within several competing forces and are frequently foregone in favour of other demands, such as cost, time or pleasure. It is within this challenged and overcrowded context that the additional consideration of including sustainability in national food dietary guidelines must be undertaken. Importantly, as these guidelines emerge, account needs to be taken of consumer responses and unintended consequences.

Nutrition scientists have yet to reach a consensus on what a SuHe diet means in practice, although discussion around sustainable dietary advice from nutritionists is not a recent phenomenon(Reference Garnett34,Reference Gussow and Clancy35) . In initiating discussion on SuHe dietary guidelines, Gussow and Clancy(Reference Gussow and Clancy35) proposed a focus on local and seasonal produce, fresh or minimally processed foods and reduced meat intake, behaviours which also supported both social and environmental sustainability. However, these ‘ideals’ attracted detractors who denounced the pursuit of a ‘social cause’(Reference Gussow36). The emerging guidance around sustainable diets suggests the need to reduce animal products with a general turn to a more plant-based diet(Reference Lonnie and Johnstone37). Nevertheless, it is not yet clear how much animal protein is both healthy and sustainable, and what would adequately replace animal protein in the diet(Reference Davies, Gibney and O’Sullivan38) if it were to be reduced beyond the current recommendation. The lack of specific guidance and practical advice on how to incorporate such recommendations into daily life has also been raised(Reference James-Martin, Baird and Hendrie39). A further issue is that recently revised dietary guidelines towards sustainability in Canada have been shown to be nutritionally inadequate for certain consumer groups(Reference Barr40). Ensuring that SuHe diets are both nutritionally adequate and environmentally friendly is a considerable ask and this is within the context of a continually evolving field of food sustainability science, with 18 separate indicators currently identified to adequately assess a diet’s environmental impact(Reference Aldaya, Ibañez and Domínguez-Lacueva41). Once defined, effective communication of SuHe diet recommendations to consumers must follow.

Past communications inform belief systems by framing the public’s understanding of healthy eating, with implications for the interpretation of any future communications(Reference Vainio, Irz and Hartikainen42). Across many countries, reframing a greater than 30-year ‘food health’ narrative towards a higher consumption of plant-based foods and a reduction in animal protein will likely be met with resistance(Reference Yule and Cummings43). This resistance, which stems from existing beliefs and practices, is further compounded by the lack of consistency in public messaging due to both a delay in the implementation of new nutritional knowledge and the multiplicity of dietary information sources available to consumers(Reference Mozaffarian and Forouhi44) including the messages framed by the food industry. Dietary guidelines are often accompanied by graphical visual formats to facilitate dissemination, including plates and pyramids to communicate proportionality of recommended food intake. Consumers do not always integrate these formats as expected, for instance, Goodman(Reference Goodman, Armendariz and Corkum45) found that in five countries the food pyramid was one of the most recalled mass media communications, even though all five use the plate model, however, three countries had previously used the food pyramid. This possibly demonstrates the effects of prior beliefs and strength of earlier associations. Account also needs to be taken of the influence of online and social media sources(Reference Shearer and Gottfried46) where nutritional information is increasingly accessed(Reference Goodman, Hammond and Pillo-Blocka47,Reference Pollard, Pulker and Meng48) . Here, consumers find an abundance of not-always accurate advice(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici25,Reference Mozaffarian and Forouhi44,Reference Denniss, Lindberg and Marchese49) , which further contributes to confusion about what to believe and who to believe, evoking frustration(Reference Brehm50), which in turn can trigger a backlash(Reference Ngo, Lee and Rutherford51,Reference Vijaykumar, McNeill and Simpson52) in the form of non-compliance. This again draws attention to the individual and their everyday practices and a need to understand the cognitive, emotional and behavioural responses to evolving dietary communications.

Dietary guidelines are intended to help consumers make healthier choices and, to ensure effective dissemination, consideration needs to be given not only to gaining consumers’ awareness but also to the related but separate processes of understanding, acceptance and adherence(Reference Brown, Timotijevic and Barnett27,Reference Khandpur, Quinta and Jaime53) . Such communications also sit within the broader environment (including sociocultural) and are delivered to a diverse population. This context influences responses (cognitive, emotional and behavioural) to such communications and is further complicated due to the range of individual characteristics that shape everyday lives. Despite over a century of good work undertaken in this domain, significant challenges in adherence to dietary guidelines exist(Reference Fernandez, Bertolo and Duncan22,Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici25,Reference Leme, Hou and Fisberg29,Reference De Ridder, Evers and Adriaanse54–Reference Scheelbeek, Green and Papier56) and as the SuHe dietary narrative continues to evolve, it has the potential to further compound existing perceived confusion and contradiction around nutritional advice(Reference Mozaffarian, Rosenberg and Uauy57).

Confusion and nutrition narratives

Nutrition narratives are contextually relevant, multi-component, rationales(Reference Morley58),which can serve to simplify and justify common beliefs that are intended to shape and reinforce dietary behaviour, for instance, ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away’ connects fruit consumption with good health(Reference Davis, Bynum and Sirovich59). New nutrition narratives, however, will need to be constructed if consumers are to adopt all dietary changes proposed by authors of sustainable reference diets, which generally advocate for minimal amounts of animal protein and daily consumption of plant protein(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4,Reference Springmann, Spajic and Clark60) amongst others. In addition to health professionals, many disciplines will need to engage with translating nutrition knowledge into actionable insights(Reference Neale and Tapsell61), ranging from policymakers to the food industry. SuHe dietary guidelines, entering a crowded information landscape, could suffer from a lack of narrative scaffolding in the mind of the consumer(Reference Hazley, Stack and Kearney62). Nonetheless, existing narratives have endured, for instance, the well-established advice to eat more fruit and vegetables is both a health, and, more recently, an acknowledged sustainable recommendation.

New narratives will challenge what is commonly accepted as normal, and prevailing certainties about normality can present a considerable barrier to the uptake of expert knowledge towards a healthful lifestyle. Nevertheless, food-related attitudes and behaviours evolve over time in line with micro and macro-environmental changes. In recent years social narratives have raised awareness of animal rights, the impact of food production and consumption on the environment and the broader health consequences of consuming processed foods and meats, among other things, resulting in consumer consideration and questioning of deeply held beliefs around what is believed to be normal from a nutritional perspective(Reference Loughnan, Bastian and Haslam63,Reference van der Weele and Driessen64) . Such consideration is precipitated through acquisition of new information. Processing nutrition information into knowledge is an important capability in enabling food choice change and precedes the expression of that knowledge through behaviour(Reference Grunert12,Reference Schruff-Lim, Van Loo and van Kleef65,Reference Thøgersen66) . Since the exercise of this capability requires attention and effort, consumers need to be motivated to invest energy and time, resources that are in short supply, in making sense of and integrating such information into existing knowledge structures(Reference Schulte-Mecklenbeck, Sohn and de Bellis67). These existing belief and knowledge structures may present challenges in any transition to a more SuHe diet, and in the development of new narratives, resulting in a potential for confusion.

Consumers have defined a SuHe diet in several ways(Reference Kenny, Woodside and Perry68), including eating a varied and balanced diet, eating fresh, seasonal, local and organic produce(Reference Kenny, Woodside and Perry68–Reference García-González, Achón and Krug70), and eating more fruit and vegetables. Less evident in these definitions are direct associations with environmental impacts of food choices, particularly the climatic impact of animal meat production and consumption(Reference García-González, Achón and Krug70–Reference Szczebyło, Rejman and Halicka72); relatedly, consumers have shown disinterest in the environmental impact of food(Reference Halicka, Kaczorowska and Rejman73,Reference Tepper, Geva and Shahar74) and distrust information sources about such matters(Reference Halicka, Kaczorowska and Rejman73).

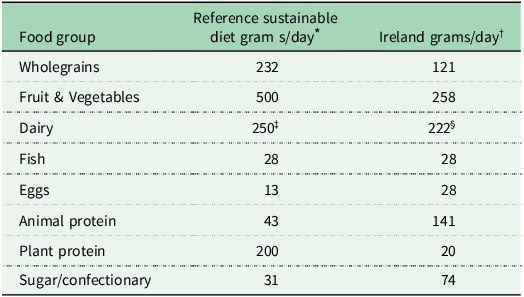

Adopting a SuHe diet will require consumers to modify existing consumption levels, as illustrated in Table 1 where such recommendations are compared to the case of the Irish population’s consumption data (NANS II, 2024). Noteworthy are the differences between animal- and plant-source protein consumption. Within this review the focus is on the protein recommendations and such food choice modifications will challenge beliefs relating to protein portion size, sources of protein and the role of processed foods. These three warrant particular attention due to the pivotal position they hold in a rapid transition towards SuHe diets. Indeed, if populations were to follow existing healthy guidelines, a positive impact on sustainability outcomes would be realised(Reference Culliford, Bradbury and Medici25).

Table 1. Recommendations from a sustainable reference diet grams/day compared to NANS II grams/day consumption in the case of Ireland’s population

* Willett et al., 2019.

† NANS II Summary Report May 2024.

‡ Whole milk or derivative equivalents.

§ Milk and dairy products i.e. cheese, yogurt, ice-cream, butter.

Portion size distortion

Sustainable reference diets variously advocate for portion sizes that are significantly less in the case of animal protein and more in the case of plant protein than developed nations’ typical consumption levels(Reference Davies, Gibney and O’Sullivan38). Linear associations have been identified since the 1960s between the increasing prevalence of overweight/obesity and increasing portion size(Reference Young and Nestle75). Consumers’ ability to accurately assess portion size has been hampered by variability in, and ambiguous definitions of, recommended servings(Reference Faulkner, Pourshahidi and Wallace76–Reference Spence, Livingstone and Hollywood78). Additionally, external cues(Reference Faulkner, Pourshahidi and Wallace76), food environment, food characteristics, individual characteristics(Reference English, Lasschuijt and Keller79,Reference Robinson and Kersbergen80) and social norms(Reference Spence, Livingstone and Hollywood78,Reference Stok, De Ridder and De Vet81,Reference Raghoebar, Haynes and Robinson82) influence consumers’ perceptions of acceptable serving sizes. Varying results have been reported on the relationships amongst portion size, energy intake and container size(Reference Papagiannaki and Kerr77,Reference Libotte, Siegrist and Bucher83) . However, as the average dinner plate size has been increasing over several decades(Reference Van Ittersum and Wansink84), and portion size has been found to effect energy intake(Reference Zuraikat, Roe and Privitera85,Reference Rolls, Morris and Roe86) , these factors may have contributed to overconsumption. Researchers have proposed that this effect of bigger plate size on portion size(Reference Faulkner, Pourshahidi and Wallace76,Reference English, Lasschuijt and Keller79,Reference Fuchs, Pearce and Rolls87,Reference Gough, Haynes and Clarke88) could provide opportunities to increase intake of fruit and vegetables(Reference Libotte, Siegrist and Bucher83,Reference Zuraikat, Roe and Privitera85) .

Heuristics, mental shortcuts to reduce cognitive load, are involved in judgements about portion sizes. Inherent beliefs that ‘if it’s larger, then it will be more satisfying’(Reference Brunstrom, Collingwood and Rogers89), ‘if it’s healthy I can eat more’(Reference Spence, Livingstone and Hollywood78) and ‘if it’s healthy it’s less filling’(Reference Suher, Raghunathan and Hoyer90) are such heuristics that are the result of observational learning and post-ingestive experiences(Reference Brunstrom, Collingwood and Rogers89). However, such beliefs appear to be inconsistently acted upon given low levels of consumption of healthy fruit and vegetables, and high levels of consumption of unhealthy discretionary foods, suggesting different rules for different foods. Consumer perception of a food’s likely hunger-reducing effect is an important consideration(Reference Brunstrom, Collingwood and Rogers89,Reference Brunstrom, Flynn and Rogers91) and may act as a barrier to making substitutions or replacements in the case of animal protein. Additionally, novel protein consumption, for instance of cultured meat products or plant-based meat alternatives, requires alterations to existing meal planning routines which are informed by a collective sociocultural intuition of the constituents and sizes of meals within a shared cuisine(Reference Brunstrom, Flynn and Rogers91).

Facilitating consumers to modify protein portion sizes, as SuHe dietary guidelines would recommend, warrants a deeper exploration of the mechanisms of modification to inform a re-orientation of portion size beliefs. Attempts to encourage consumers to curtail animal-source protein and increase plant-source protein consumption could be hampered by concerns about satiety and social acceptability of such portion size modifications.

Animal-source protein reduction and transition to plant-source protein

Reducing meat consumption is established as an impactful sustainable food choice(Reference Willett, Rockström and Loken4,Reference Chevance, Fresán and Hekler92–Reference Romanello, Di Napoli and Drummond95) . Notwithstanding this, the positive health outcomes relating to animal protein in the diet are well documented while adverse outcomes are contested(Reference Stanton, Leroy and Elliott96). The complexity of the issue of animal protein reduction is set within the context of competing concerns from alternative-protein, plant-based, agri-techno and agri-ecological perspectives(Reference Duluins and Baret97,Reference Maye, Fellenor and Potter98) . Such perspectives challenge established nutrition narratives in the consumer’s mind, for instance, are processed, unfamiliar and imported plant-based meat alternatives healthier and more environmentally and economically sustainable than locally produced beef and dairy. A further consideration is that SuHe dietary messaging could force consumers to confront and rationalise competing concerns that cause a psychological discomfort known as cognitive dissonance(Reference Dowsett, Semmler and Bray99–Reference Wehbe, Banas and Papies101). Consumers have been shown to employ dissonance reduction strategies to facilitate self-serving behaviours and maintain deeply rooted beliefs and traditions while preserving moral principles(Reference Dowsett, Semmler and Bray99). Indeed, rationalisations that carnism is normal and necessary enable a reconciliation of the cognitive dissonance triggered by feeling both concern for animals and pleasure when eating meat(Reference Piazza, Ruby and Loughnan102).

Meat attachment, characterised by positive and intense affective connections to meat, is associated with masculinity(Reference Graça, Calheiros and Oliveira103,Reference Love and Sulikowski104) and low willingness to change habits(Reference Graça, Truninger and Junqueira105). The meat and masculinity narrative has endured as a social norm and cultural paradigm since its origins in the late 1800s, shaping gendered food practices(Reference Nungesser and Winter14). With industrialisation, meat became commoditized and differentiated based on quality, with higher-status individuals preferring leaner, more easily digestible, better cuts of meat and hence meat came to represent status, a social norm which prevails(Reference Chan and Zlatevska11).

Options to reduce animal-source protein consumption through plant-protein replacement include whole food (lentils, beans, peas) and processed alternatives. Processed replacement product solutions have developed along two lines: plant-based meat alternatives, which historically were developed for vegetarians and vegans; and the cultured meat alternative, a recent innovation targeted at omnivores, which involves taking cells from animals and growing meat in a laboratory. The likelihood of consumer acceptance and adoption of the latter is not straightforward(Reference Malek and Umberger106–Reference Pakseresht, Kaliji and Canavari108). In one alternative-protein study, ambivalence, ambiguity and uncertainty were evoked about both current and future protein choices when consumers were presented with cultured meat products(Reference van der Weele and Driessen64), provoking dilemmas about what is natural and normal. Plant-based meat alternatives and lab-cultured meat products involve a degree of processing, using methods and ingredients consumers will not recognise nor have access to in their household, thus raising concerns about the artificial nature of such food, which may in turn act as barriers to consumption. As these food innovations emerge, many will fall into the ultra-processed food (UPF) category.

The rise and role of ultra-processed food (UPF)

UPF provides both affordable and fortified food to address micronutrient deficiencies in addition to facilitating food waste reduction(Reference Forde109,Reference Hess, Comeau and Fossum110) ; however, the contested issues of classification, adverse health outcomes and environmental impacts, which are not fully understood, remain unresolved(Reference Gibney, Forde and Mullally111–Reference van Hensbergen113). Furthermore, the established links between certain UPF consumption and worsening public health are cause for concern(Reference Levy, Barata and Leite114,Reference Martines, Machado and Neri115) . UPF are classified under the NOVA system as ‘not modified foods but formulations made mostly or entirely from substances derived from foods and additives with little if any intact food’. The usefulness of the NOVA system has been contested, nevertheless, UPF have become increasingly common in the diets of developed countries, due to the appealing presentation and palatability of such products(Reference Hall, Ayuketah and Brychta116,Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac117) . Increasing palatability of UPF generally involves the addition of sodium, salt and/or sugar and consumption of a UPF diet has been shown to increase both energy intake and weight gain compared with a minimally processed diet(Reference Hall, Ayuketah and Brychta116). In Europe, several countries have the highest sales globally of UPF, averaging 140 kg/capita, of which the largest category is baked goods(Reference Vandevijvere, Jaacks and Monteiro118). However, as UPF is ubiquitous(Reference Chazelas, Druesne-Pecollo and Esseddik119) it may be neither practical nor, some authors argue, ethical to recommend their elimination, offering as they do familiar and affordable sources of nutrients to consumers(Reference Forde109,Reference Hoek, Pearson and James120) . The concern in devising low-carbon diets, however, is that certain UPF, for instance, sugary snacks, have been found to be amongst the lowest greenhouse gas emitting foods(Reference Hyland, Henchion and McCarthy121) and these UPF tend to be energy-dense and nutritionally poor. Indeed, there is evidence of recent food policy efforts to improve the nutrient profiles of UPF through reformulation to reduce problematic levels of sodium, sugar and saturated fats(Reference Forde109,Reference Hyland, Henchion and McCarthy121) .

Overcoming the perceived unnaturalness of UPF has been a focus for the food industry. Consumers exhibit a naturalness bias with strong positive associations towards food they believe to be ‘natural’(Reference Román, Sánchez-Siles and Siegrist122,Reference Schirmacher, Elshiewy and Boztug123) to such a degree that ‘natural’ is a highly attractive food attribute, and in consumers’ minds additives are perceived to be a contamination of natural food(Reference Rozin124). Unsurprisingly food product marketing campaigns are cognisant of this and employ related words on labels as an effective heuristic in a manoeuvre that strengthens purchase intentions(Reference Schirmacher, Elshiewy and Boztug123) and enables consumers to ignore the processed nature of the products they purchase. Psychological strategies that enable consumers to purchase processed snacks include ‘permissible indulgence’(125) and the employment of ‘natural’ and ‘nutritious’ heuristics as assurances that they are treating themselves, but with a healthy product. Snacks can offer a convenient solution to improving micro- and macronutrient consumption, for instance, amino acids, protein and fibre(Reference On-Nom, Promdang and Inthachat126), using plant-based sources, however dietary guidelines generally recommend limiting snacking(Reference Hess, Jonnalagadda and Slavin127) as the activity is associated with consumption of energy dense foods. As consumers are confronted with food product innovations that offer plant-based and lab-cultured meat alternatives(Reference Hocquette, Chriki and Fournier128), traditional belief systems based on ‘natural, normal, necessary and nice’ will be challenged.

There are signs though that consumers are altering food preferences(129,Reference Pellinen, Jallinoja and Erkkola130) where association with the flexitarian food-based lifestyle is on an upward trajectory, even as recent market reports(Reference Battle, Pierce and Carter131) suggest that interest in vegan food is waning. These trends in lifestyle associations(Reference Aiking and de Boer132), involving curtailment of animal-source protein, suggest consumers’ food-related ideologies are changing. Understanding why and how such a re-examination of food beliefs and subsequent behaviours is triggered could shed light on promising prompts for those who have not yet engaged in similar SuHe dietary modifications.

Changing consumers’ beliefs

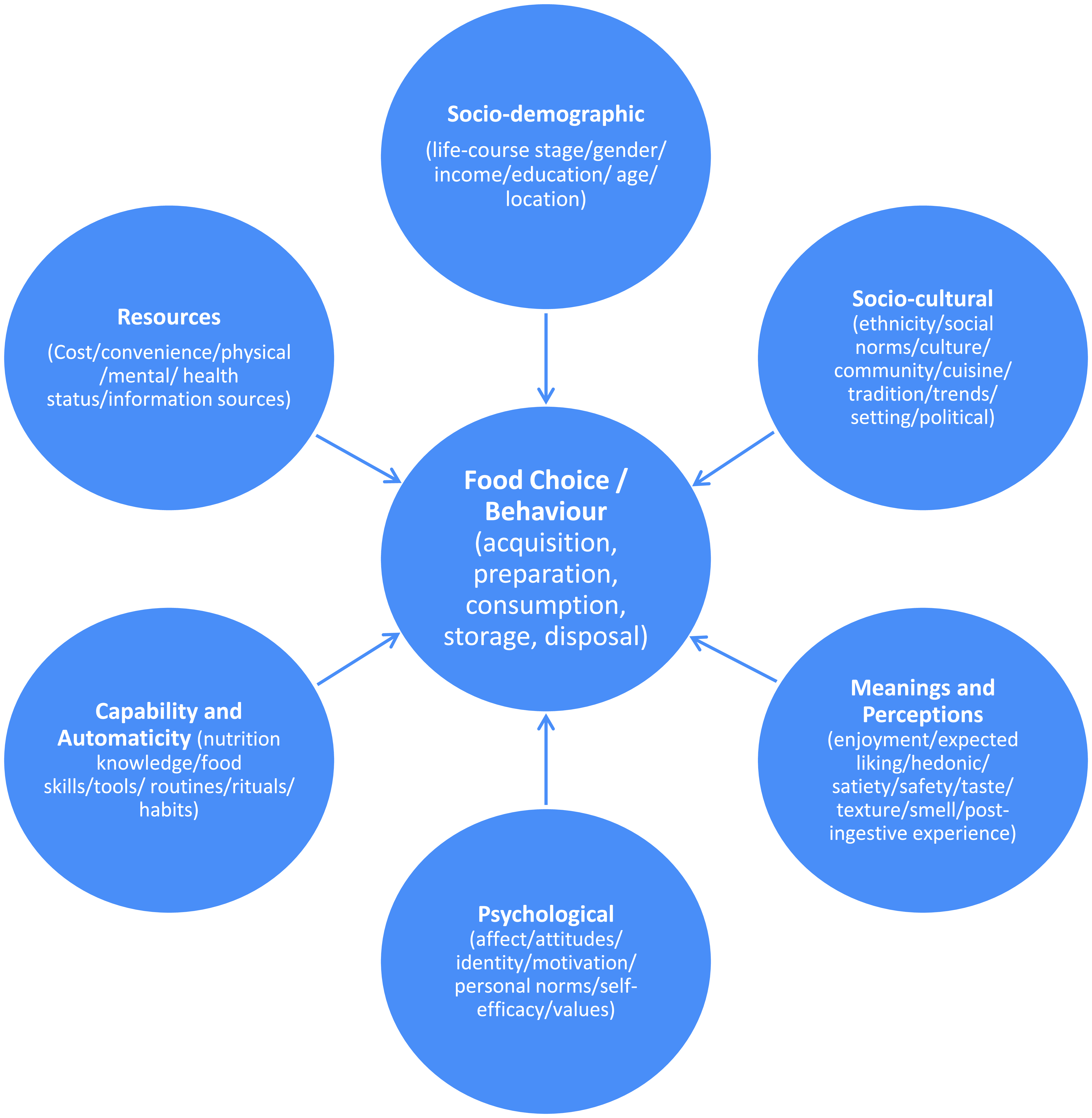

Food choices change and evolve over time(Reference Jabs and Devine133), involving a ‘negotiation of contested meanings’(Reference Mezirow134,Reference Kerton and Sinclair135) . Evolutions can be tied to so called ‘fractures’ in a person’s food choice trajectory, which can either reinforce or alter food practices(Reference O’Neill, Clear and Friday10), for instance, health and climate change concerns have the potential to cause consumers to confront previously accepted thoughts, feelings and actions about their food system. This critical reflection and examination, with the resulting decision to act and change food choice behaviour, is arguably ‘one of the more dramatic actions that an individual can take’(Reference McDonald, Cervero and Courtenay136). The idea that a life’s sustenance and a body’s fuel will not sustain humans, nor the planet, in the future, could conceivably have a disorienting impact(Reference Kerton and Sinclair135). Such disorientation could lead to transformative change whereby a multitude of factors influencing food behaviour at the individual level(Reference Sobal and Bisogni16,Reference Afshin, Micha, Khatibzadeh, Brown, Yamey and Wamala137–Reference Eertmans, Victoir and Vansant139) are affected. These factors are summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Micro-level factors influencing consumer food behaviour.

Consumers’ dietary-related attitudes, beliefs, emotions, identity and values would need to modify in a way that facilitates acquisition of new beliefs about ‘good food’ and the constituents of a meal, new food preparation, knowledge and skills, and daily enactment of modified food acquisition, preparation and consumption rituals and routines. Understanding how consumers make such transitions warrants consideration of the literature on belief typology, formation and transformation.

Considering the dynamics of attitudes, beliefs, emotions and knowledge – a route to better engagement with nutritional information

Changing consumer behaviour towards the new hybrid construct of a SuHe diet requires contributions from both health and environmental psychology to effectively frame a unique behaviour change process. Such a process potentially will be fuelled by diverse beliefs, propelled by multiple and non-traditional health motives(Reference Verain, Raaijmakers and Meijboom140) and involving resolutions of conflicts and tensions. In particular, barriers to new belief formation, including unresolved dilemmas relating to the environmental and health impacts of food choices, and the evoked emotions when confronted with unfamiliar dietary recommendations require further investigation.

Broadly, a belief can be defined as ‘the mental acceptance or conviction in the truth or actuality of some idea’(Reference Schwitzgebel141), and critical to the enablement of consumers in making sense of their social world(Reference Connors and Halligan142). Many beliefs are likely to operate at an unconscious level, are not directly observable and can only be inferred from behaviour(Reference Zwickle, Jones, Leal Filho, Marans and Callewaert143). Our food-related belief systems are complex to untangle given that they facilitate the holding of conflicting views within the same subject, and do not always relate to objective reality, as evidenced by the low associations consumers continue to make between food choices and their environmental impacts(Reference Connors and Halligan142,Reference Hartmann, Furtwaengler and Siegrist144,Reference Dowsett, Semmler and Bray99,Reference Bendaña, Mandelbaum, Borgoni, Kindermann and Onofri145) .

Within SuHe food behaviour research, support has been found for a particular set of relationships between belief types and behaviour(Reference Bourke, McCarthy and McCarthy146). Ajzen(Reference Ajzen147,Reference Ajzen148) , for instance, has posited that intention is a predictor of behaviour enactment, while attitudes (determined by weighted evaluations of perceived consequences of behavioural enactment based on readily accessible behavioural beliefs), social norms (normative beliefs based on perceived expectations and behaviours of others) and perceived behavioural control (PBC: determined by control beliefs based within perceived presence of obstacles and facilitators to behavioural enactment) predict intention. However, unexplained variance and inconsistencies across both health and particularly sustainable food-related behavioural studies persist(Reference Grandin, Boon-Falleur, Chevallier, Musolino, Sommer and Hemmer149,Reference Johnstone and Tan150) . This behavioural phenomenon is well established and has been varyingly termed the ‘intention-behaviour’ gap(Reference Onwezen, Verain and Dagevos151–Reference Stubbs, Scott and Duarte153), the ‘value-action’ gap(Reference Babutsidze and Chai154), the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’(Reference Meyer and Simons155) and the ‘belief-behaviour’ gap(Reference Grandin, Boon-Falleur, Chevallier, Musolino, Sommer and Hemmer149), as in the case of reduced meat consumption intentions(Reference Dagevos and Verbeke156). Accessible beliefs sit within motivational processes including goal-directed behaviour and conscious self-regulatory processes(Reference Ajzen157), thereby rendering them less effective in explaining amotivation and belief formation mechanisms. These latter elements are likely to characterise change towards SuHe food choices given consumer inertia(Reference Grin, Grin and Spaargaren20,Reference Webb and Byrd-Bredbenner158) , cognitive dissonance(Reference Dowsett, Semmler and Bray99) and deliberate ignorance(Reference Kadel, Herwig and Mata159), which are less well understood in terms of their impact on attitudes, beliefs and values. If new nutrition information is to successfully enter consumer consciousness, attention to the process of belief formation is required.

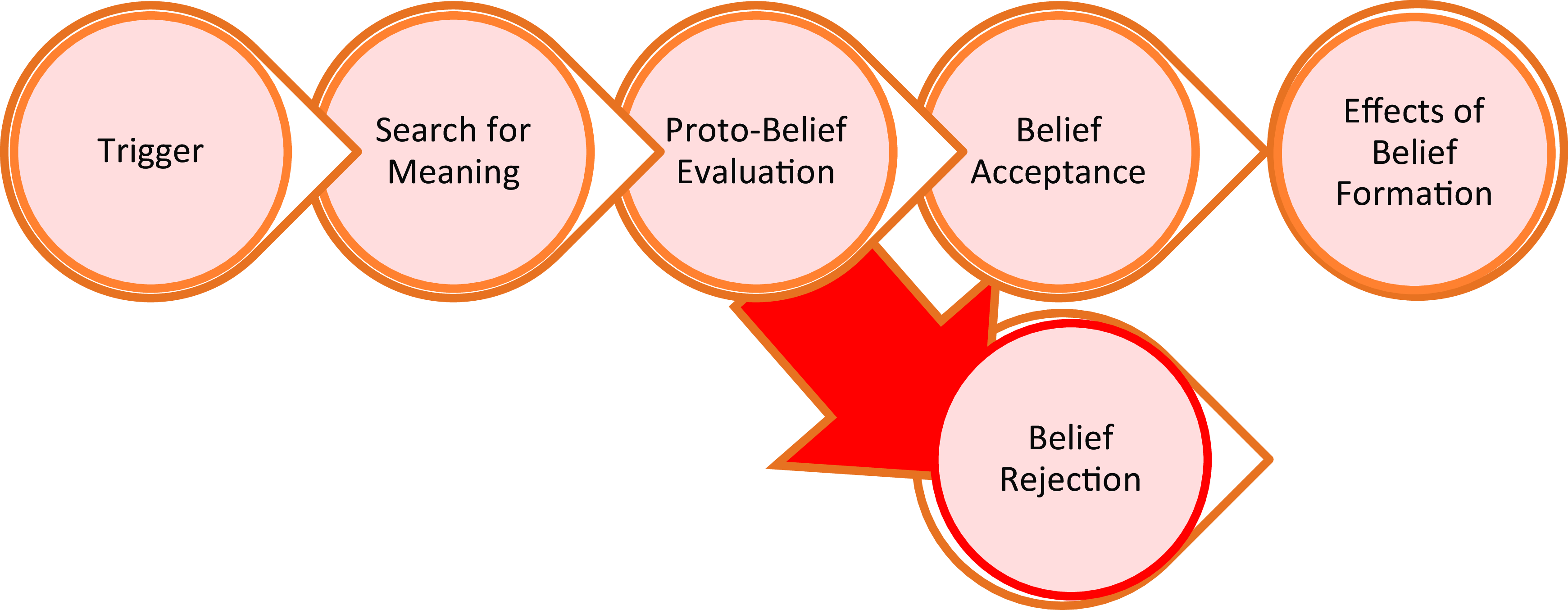

Belief formation is precipitated by a precursor or triggering event that catalyses a series of evaluatory(Reference Connors and Halligan142) or transformation stages(Reference Mezirow134) as depicted in Fig. 2. The trigger, or disorienting dilemma, is characterised by an unexpected or unusual input occurring, entering awareness through a variety of channels, for instance, a General Practitioner visit, newspaper article or a self-reflection. For belief acceptance to occur, the evaluation of the ‘proto-belief’ depends on adequate explanation of the trigger, which is consistent with existing beliefs. A belief acquisition or rejection process is activated(Reference Gilbert160,Reference Mezirow134) . Belief formation accounts have tended to ignore the emotional and social factors that complicate such processes(Reference Mälkki, Fleming, Kokkos and Finnegan161) however, evidence for the affective nature of disorienting dilemmas in the production of cognitive dissonance(Reference Spannring and Grušovnik162,Reference Stuckey, Peyrot and Conway163) and in the maintenance of our emotional comfort zones(Reference Mälkki, Fleming, Kokkos and Finnegan161), has relevance here. Emotion-based triggers may present critical thresholds to belief modification as they play a role in protecting established and traditional food-related beliefs.

Fig. 2. Stages of Belief Formation (adapted from Connors & Halligan, 2015).

Thinking about SuHe dietary change evokes affective responses in consumers. Emotions differ based on existing beliefs/lifestyles, the food product under consideration and the social setting/context. For instance, those who favoured reduction or elimination of animal protein or followed a vegan/vegetarian diet expressed indignation, disgust and anger about meat consumption, and pride and joy about their lifestyle and about ‘being trendy’(Reference Hoek, Pearson and James164,Reference Sahakian, Godin and Courtin165) . Omnivores, on the other hand, expressed feelings of being threatened, of fear, and irritation, and were disapproving in response to the idea of meat curtailment, expressing contempt towards those who curtailed or avoided meat, and powerlessness about reducing environmental impact through personal food choices(Reference Sahakian, Godin and Courtin165,Reference Macdiarmid, Douglas and Campbell166) . Feelings of ambivalence, curiosity, disgust, worry and lack of safety were associated with consumption of UPF(Reference Hoek, Pearson and James120,Reference Sahakian, Godin and Courtin165,Reference Michel, Hartmann and Siegrist167) . Social settings can affect willingness to consume alternative-to-meat proteins with evidence for anticipated fun/excitement on one hand(Reference Motoki, Park and Spence168) however, Michel et al. (Reference Michel, Hartmann and Siegrist167) found contrary evidence, where consumers associated such consumption willingness with eating alone or in small familiar groupings, suggesting a fear of judgement. This highlights the interplay amongst attitudes, normative beliefs and affect in shaping certain SuHe food choice behaviour(Reference Constantino, Sparkman and Kraft-Todd169).

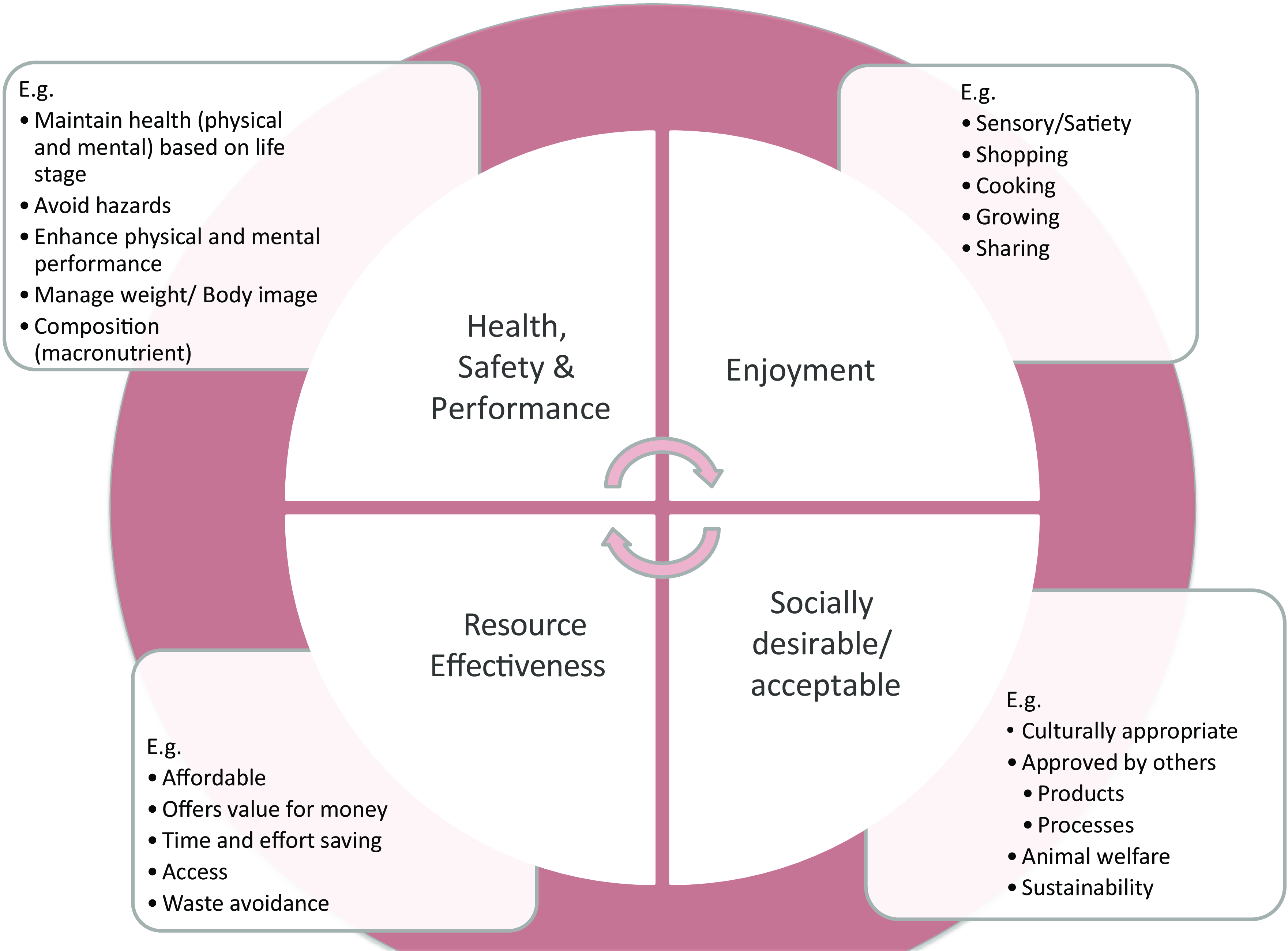

The transition to SuHe dietary choices will involve engaging with recommendations that challenge consumers’ ways of thinking about food choices, as depicted in Fig. 3, resulting in disorientations possibly to do with replacement and curtailment of much-loved and familiar foods. For instance, many consumers believe meat consumption contributes to their health, eating enjoyment, and is accessible and socially acceptable. Asking those consumers to curtail animal-source protein therefore can trigger perplexity. In other words, any suggested changes to diet for sustainability reasons would involve a reconsideration of many of the factors highlighted in Fig. 3. Such disorientation may evoke dissonance, ambivalence or other emotions, and such evocation may increase or diminish acceptance and a willingness to explore alternatives and acquire new knowledge. The settings within which sustainability-related disorienting dilemmas have been found to manifest are non-structured and unintended (moral dilemmas or existential crisis or past socio-ecological problems), structured and unintended (new learning environment or new social interactions) and structured and intended (educational programme)(Reference Rodríguez Aboytes and Barth170). This suggests that the most promising routes to SuHe food transformation are therefore most likely through channels including a personal health crisis, an awareness of the environmental impact of food choices, an expansion of social networks and information campaigns, prompting critical self-reflection. There are indications in the sustainable literature that the accumulation of knowledge could act as a trigger to provoke such critical examination of habitual ways of thinking and feeling(Reference Carmi, Arnon and Orion171) and a re-evaluation of values and attitudes(Reference Scalvedi, Gennaro and Saba30,Reference AlBlooshi, Khalid and Hijazi172–Reference Verain, Sijtsema and Antonides174) .

Fig. 3. Consumers’ food choice concerns.

Within consumer behaviour, there are two clearly differentiated knowledge components: objective or accurate stored information(Reference Carlson, Vincent and Hardesty175) and subjective or perceived knowledge(Reference Carmi, Arnon and Orion171,Reference Pieniak, Aertsens and Verbeke176,Reference Radecki and Jaccard177) . Subjective knowledge has been found to be the stronger predictor of behaviour(Reference Pieniak, Aertsens and Verbeke176) and associated with higher levels of self-confidence in decision-making(Reference Brucks178). This suggests that, as consumers are likely more motivated to behave in ways congruent with what they believe they know than what is factually accurate, new nutrition information may not be taken at face value and must fit into an established belief system. The effect of this reliance on subjective knowledge is to lower the inclination to search for information to enhance knowledge(Reference Radecki and Jaccard177). Subjective knowledge is related to ‘understanding’, which demonstrates personal ownership for and care about the subject matter over ‘knowing’ factual objective information(Reference Carmi, Arnon and Orion171). This affective element, ‘care for’, has received particular attention in environmental behavioural research where relationships amongst emotional engagement and values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviour towards the environment has been demonstrated(Reference Carmi, Arnon and Orion171,Reference Kollmuss and Agyeman179) . The notion of ‘head, heart, and hands’ in the transformation of knowledge to action(Reference Carmi, Arnon and Orion171,Reference Kollmuss and Agyeman179) reflects the relationships amongst belief (cognitive), emotion (affective) and action (behaviour). In considering consumers’ SuHe dietary behaviour inertia, it is likely that inaccurate subjective knowledge relating to the topics discussed earlier, portion size, animal-sourced protein and UPF, is preventing action planning at some level(Reference Mercier, Altay, Musolino, Sommer and Hemmer180).

The connections between knowledge, attitudes, affect, understanding and beliefs, as summarised above, explain, in part, why provision of information does not necessarily impact behaviour. This demands that policymakers put less focus on presenting facts and more focus on the routes to motivating a behavioural response from consumers, with the support of insights from the social sciences and consideration of the environments within which information is received(Reference Mercier, Altay, Musolino, Sommer and Hemmer180). Indeed, Mozaffarian et al. (Reference Mozaffarian, Rosenberg and Uauy57) highlighted the importance of the setting in nutrition promotion effectiveness, noting reach in the health care system as limited. Such settings would acknowledge the importance of facilitating consumers, for instance with the provision of personalised nutrition, to resolve confusions in ways that facilitate planning and action(Reference Davies, Gibney and O’Sullivan38).

At another level, the lack of a collective approach amongst health nutritional professionals (HNP) hampers communication of aligned SuHe priorities(Reference Kenny, Woodside and Perry68,Reference Carlsson and Callaghan181,Reference Pettinger, Tripathi and Shoker182) , amongst other factors. Positively, both nutritionists and nutrition students have expressed interest in acquiring more knowledge about sustainable diets and practices to enable client education(Reference Baungaard, Lane and Richardson183,Reference Heidelberger, Smith and Robinson-O’Brien184) . However, there are many questions to answer, and a minority are concerned with the appropriateness of such development for the profession before there is greater clarity(Reference Carlsson and Callaghan181). Nonetheless, HNP possess the skills and expertise to be the translators of scientific information into public knowledge and hence common practice. Efforts to ensure nutrition research translates into trusted, usable knowledge through social learning, knowledge governance, nutrition leaders’ consensus and collaboration amongst multi-disciplinary stakeholders is warranted(Reference Fernandez, Bertolo and Duncan22,Reference Mozaffarian, Rosenberg and Uauy57,Reference Clark, Van Kerkhoff and Lebel185) .

Conclusion

In the next evolution of dietary guidelines, respect for the role of the individual in the transformation of food behaviour is at the core of the behaviour change ecosystem(Reference Afshin, Micha, Khatibzadeh, Brown, Yamey and Wamala137). Beliefs around food are embedded within experience and evolve over time. Revising food-based dietary guidelines towards sustainability presents an opportunity to change food choices, however the ‘asks’ within that opportunity may represent a disorientation for individuals as existing food beliefs are deep-seated and slow to change. An immediate challenge is identifying mechanisms to engage individuals in a process of reimagining the meaning of food within society. It is proposed here that such a process will involve triggering a scrutiny of traditional, and previously unexamined, food-related beliefs. Some consumers have begun the transition towards a SuHe diet, however, it appears from current consumption levels and health data that most consumers have not engaged in transforming food behaviour. While consumers may not be actively resistant, the risk is that such asks that provoke confusion could induce cognitive conflict, deepening inertia and inaction. The SuHe dietary transformation must occur within a food system where dietary communications, retail environments, food production systems and policy measures support society. Those stakeholders involved in the production of scientific information must quickly convert it into usable knowledge and investigate further the mechanisms through which SuHe dietary knowledge transforms behaviour. This requires a multi-disciplinary effort if the greatest health challenge of our time, the ‘Global Syndemic’, is to be effectively addressed.

Acknowledgements

DAFM and DAERA had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. This review paper is part of a body of papers from the SuHeGuide research project, acknowledging insights from the SuHe research team.

Author contributions

MBM, BCB and SNM conceptualised the article. BCB produced a first draft, with significant additions and revisions from MBM and SNM. All authors approved the final version of the article for submission.

Financial support

The SuHe Guide project is funded through the Department of Agriculture, Food, the Marine (DAFM)/ Food Institutional Research Measure (grant number: 2019R546), and Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) (grant number 19/R/546).

Competing interests

We have no conflict of interest to report.

Data sharing statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.