Since his inauguration on 20 January 2025, United States president Donald Trump and his administration have been advancing an unprecedented attack on the power and political neutrality of the federal government’s career bureaucracy. This attack includes, among other actions, lambasting the bureaucracy, sacking civil servants and inducing them to resign, the closure of agencies and programs, and the sign-off of an executive order reclassifying tens of thousands of career civil service positions, enabling dismissal based on partisan orientation (The Economist 2025). Similar, albeit less overt, attempts by politicians to weaken and co-opt bureaucracies are common facets of the global phenomenon of “democratic backsliding” (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Peters, Pierre, Yesilkagit and Becker2021).

Democratic backsliding involves attacks by democratically elected political leaders and parties on citizens’ freedoms and civil rights, the subversion of the electoral process, and “executive aggrandizement” (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016)—that is, curtailing the decision-making or scrutiny powers of institutions such as legislatures, the judiciary, the press, academia, or civil society organizations (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019; Waldner and Lust Reference Waldner and Lust2018). Acknowledging that undermining bureaucratic power and legitimacy is integral to executive aggrandizement, recent public administration studies examine how bureaucrats respond to authoritarian populists’ strategies vis-à-vis the bureaucracy (Kucinskas and Zylan Reference Kucinskas and Zylan2023; Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024; Story, Lotta, and Tavares Reference Story, Lotta and Tavares2023), and to illiberal or harmful policies (Guedes-Neto and Peters Reference Guedes-Neto, Peters, Peters, Bauer, Pierre, Yesilkagit and Becker2021; Hollibaugh, Miles, and Newswander Reference Hollibaugh, Miles and Newswander2020; Schuster et al. Reference Schuster, Mikkelsen, Correa and Meyer-Sahling2022). Are they inclined to leave, exercise their voice, covertly resist, or succumb to power?

Extant research takes it for granted that bureaucrats identify violations of democracy as detrimental, illiberal, and undemocratic. We, however, suggest that bureaucrats’ responses are likely shaped by their divergent perceptions of democratic backsliding, which tends to co-occur with populism, and animosity between political camps (Orhan Reference Orhan2022). In such polarized political contexts, bureaucrats, as members of the polity, may stand on opposing sides of a partisan divide, leading them to diverge in their perceptions of the objective reality of democratic backsliding (hereafter “perceptions of democratic backsliding”). Furthermore, we anticipate that bureaucrats’ perceptions of democratic backsliding influence their projections about the likelihood of civil service politicization and changes to bureaucrats’ policy influence, shaping their inclination to exit the civil service, exercise their voice, and exert effort at work.

We examine these propositions in the context of Israel’s high political polarization and its extreme right-wing populist government’s advancement of what we call the “legal overhaul” in 2023. This agenda, which exemplifies the global phenomenon of democratic backsliding and which has fueled mass social protests, involved an attempt to curtail the powers and independence of Israel’s Supreme Court and replace career-based government legal advisers with political appointees. This makes Israel a pertinent case for examining civil servants’ responses to democratic backsliding within the politically polarized context in which they are embedded as citizens.

To investigate bureaucrats’ perceptions and responses, we employ a mixed-methods design, combining a survey—including closed questions and free comments—of midlevel and senior career civil servants in central government with interviews and a focus group. We find that bureaucrats, given their social embeddedness as citizens among opponents and supporters of the legal overhaul, differ in their inclination to perceive it as a threat to Israel’s democracy. Moreover, our quantitative statistical analyses suggest that the more bureaucrats perceive the legal overhaul to be a threat to democracy, the stronger their intention to exit government, and the weaker their intention to exercise their voice and exert effort at work. These associations are partly mediated by bureaucrats’ concerns about increased politicization and the curtailment of their policy influence. Elucidating these findings, qualitative data analysis suggests that bureaucrats who perceive the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy are contemplating leaving not only due to politicization and curtailed influence but more broadly because they experience a threat to their professional identity as civil servants. These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of bureaucrats’ responses to democratic backsliding.

Below we discuss extant research and its shortcomings, and lay out our analytical framework and hypotheses. We then map out the context and present our research methods and quantitative and qualitative findings. We conclude by summarizing the findings and discussing their implications for the debate about the potency of the bureaucracy as a guardian of liberal democracy (Ingber Reference Ingber2018; Yesilkagit et al. Reference Yesilkagit, Michael Bauer and Pierre2024).

Democratic Backsliding and the Bureaucracy

The novel research on populism, democratic backsliding, and bureaucracy examines politicians’ strategies and bureaucrats’ responses. Several studies analyze the strategies that authoritarian populists adopt, once in power, toward the civil service (Bauer and Becker Reference Bauer and Becker2020; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Peters, Pierre, Yesilkagit and Becker2021; Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019; Reference Peters and Pierre2022). Attempts at sidelining the bureaucracy are prevalent and achieved via multiple avenues. One involves politicization, including patronage appointments from outside the civil service (Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019), promotion of loyalists from within the bureaucracy, and either dismissing or pressuring “disloyal” civil servants to resign (Bellodi, Morelli, and Vannoni Reference Bellodi, Morelli and Vannoni2022; Story, Lotta, and Tavares Reference Story, Lotta and Tavares2023). More durable forms of politicization include revising legal protections to enable personnel purging and replacement (Moynihan Reference Moynihan2022a; Reference Moynihan2022b). A related strategy involves the circumvention of career bureaucrats by centralizing decision-making powers at the hands of political nominees (Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024; Moynihan Reference Moynihan2022a; Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019), excluding civil servants from decision-making and information circles. It further involves shifting budgets and resources to existing or newly created units populated with loyalists (Dussauge‑Laguna Reference Dussauge-Laguna2022; ‑González-Vázquez, Nieto‐Morales, and Peeters Reference González-Vázquez, Nieto‐Morales and Peeters2024 ; Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019), alongside cuts in bureaucratic units considered liberal (Drezner Reference Drezner2019; Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024; Moynihan Reference Moynihan2022a). The above strategies are typically coupled with verbal attacks on the bureaucracy (Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024; Moynihan Reference Moynihan2022a).

A second, more limited research strand, to which this article contributes, analyzes bureaucrats’ responses to democratic backsliding. Studies carried out in the US during the first Trump presidency (Hollibaugh, Miles, and Newswander Reference Hollibaugh, Miles and Newswander2020) and in Brazil during the presidencies of Jair Bolsonaro and Michel Temer (Guedes-Neto and Peters Reference Guedes-Neto, Peters, Peters, Bauer, Pierre, Yesilkagit and Becker2021; Schuster et al. Reference Schuster, Mikkelsen, Correa and Meyer-Sahling2022), examine bureaucrats’ responses to fictitious illiberal or detrimental policies. They find that the nature of policies, and bureaucrats’ “public service motivation” (Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990), shape the propensity of civil servants to engage in voice, exit, and sabotage. While important, these studies do not capture whether and how variation in bureaucrats’ perceptions of politicians’ attacks on democracy shape their responses. Instead, they measure respondents’ reactions to policies, which the researchers specify as detrimental to the public interest. Thus, they overlook the likely variation in bureaucrats’ judgments about real-world leaders and their agendas.

Transcending the focus on bureaucrats’ responses to fictitious policies, Story and colleagues’ (Reference Story, Lotta and Tavares2023) study in Brazil and Kucinskas and Zylan’s (Reference Kucinskas and Zylan2023) research in the US examine bureaucrats’ responses to the Bolsonaro and Trump administrations and their strategies vis-à-vis bureaucracy (e.g., its politicization). Both studies find bureaucratic withdrawal and limited active resistance. Story and colleagues (Reference Story, Lotta and Tavares2023) find that bureaucrats’ perceptions of Bolsonaro’s political appointees as “illegitimate outsiders” induced them to opt for silence due to self-defense, a sense of inefficacy, and estrangement. Kucinskas and Zylan (Reference Kucinskas and Zylan2023) show that bureaucrats’ commitment to political neutrality restricted their propensity to oppose the Trump administration. These studies lack explicit examination of whether and how civil servants’ diverse perceptions of the threat politicians’ actions pose to the democratic regime influence their responses.

Analytical Framework

This research examines to what extent and how variation in career civil servants’ perceptions of democratic backsliding affects their willingness to contribute to government work as reflected in their intentions to exit government (Hirschman Reference Hirschman1970), exercise their voice about work-related issues (Van Dyne and LePine Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998), and exert effort at work (Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997).

Studies conducted outside the context of eroding democracies suggest that career civil servants seldom leave government when they are misaligned with their political executives’ ideology and policy (Spenkuch, Teso, and Xu Reference Spenkuch, Teso and Xu2023), though they may reduce their work efforts (Piotrowska Reference Piotrowska2024; Richardson Reference Richardson2019; Spenkuch, Teso, and Xu Reference Spenkuch, Teso and Xu2023). The vast majority are inclined to stay because they are socialized to serve any elected government impartially (Bischoff Reference Bischoff2023); are committed to their organizations, colleagues, and citizen-clients (Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997); and because their skills are often nontransferable to the private sector (Bertelli and Lewis Reference Bertelli and Lewis2012). Moreover, in closed bureaucratic systems (Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Reference Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell2012) like Israel, where recruitment for senior positions is mostly internal, civil servants’ exit is further deterred by institutional barriers to reentry. However, when confronted by contentious acts of democratic backsliding by populist politicians, civil servants’ identities as citizens who belong to different political camps likely exert a stronger effect on their willingness to contribute, including on their inclination to exit.

To theorize civil servants’ responses to democratic backsliding, we draw upon social identity theory (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1982), and, within that, on political psychology studies of citizens’ partisan identities (Huddy, Mason, and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015). Social identity involves individuals’ cognitive self-categorization as members of a group (e.g., a political party and its supporters), and their affective attachment to this group. This attachment is embedded in social interactions, reflecting and stemming from individuals’ cohesive networks of like-minded family and friends (Burt Reference Burt2004). Such attachment may induce “affective polarization,” involving positive affect toward one’s in-group and animosity toward counterpartisans (Bassan-Nygate and Weiss Reference Bassan-Nygate and Weiss2022; Gidron, Adams, and Horne Reference Gidron, Adams and Horne2020; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Individuals have multiple identities, and the relative salience of their different identities changes with context. Contentious political debates, as in the case of the Israeli legal overhaul, activate partisan identities (Sorace and Binzer-Hobolt Reference Sorace and Hobolt2021). When partisan identities are activated and affective polarization is high, individuals are inclined to engage in motivated reasoning (Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006). Namely, they are incentivized to seek out and easily accept information and argumentation that cohere with their party’s positions, and to doubt and exert effort in disputing counterevidence and arguments. Motivated reasoning is among the key explanations for the inclination of citizens to justify and rationalize executive aggrandizement when it is advanced by the leadership of their preferred party (Braley et al. Reference Braley, Lenz, Adjodah, Rahnama and Pentland2023; Bryan Reference Bryan2023; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2023; Simonovits et al. Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022; Singer Reference Singer2023). Similarly, Gidron and colleagues (Reference Gidron, Margalit, Sheffer and Yakirforthcoming) show that Israelis’ support for the legal overhaul diverged along party-bloc lines and was amplified among supporters of the governing coalition by affective polarization between them and opposition supporters.

Building on the above explanation for partisan citizen responses to democratic backsliding, we expect career civil servants’ responses to be shaped by their dual social identities as government professionals and citizens in polarized political contexts (cf. Gilad and Alon-Barkat Reference Gilad and Alon‐Barkat2018). Insofar as civil servants are socially embedded, as citizens, among both supporters and opponents of the governing coalition, they too are likely to hold disparate evaluations of executive aggrandizement. Civil servants who support the governing coalition are motivated, in line with their close social circle, to perceive the government’s executive aggrandizement as benign. They do not see it as a threat to the quality of democracy, nor to their capacity to serve the public as civil servants. Conversely, civil servants who support the opposition are likely to perceive executive aggrandizement as a menace to liberal democracy, in tandem with their social in-group. Consequently, as government employees, they may be concerned about being personally coerced to partake in, or collectively associated with, actions that conflict with their commitment to the rule of law (Christensen and Opstrup Reference Christensen and Opstrup2018), to expertise, and to their role as guardians of the public’s interests (De Graaf Reference De Graaf2011; Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990; Selden et al. Reference Selden, Brewer and Brudney1999). We therefore expect them to experience a threat to the positive meaning and self-esteem they attach to their role as government professionals, and to consider leaving the civil service to avoid this “identity threat” (Petriglieri Reference Petriglieri2011). If inclined to stay, such civil servants may disengage and forego exercising their voice and exerting effort at work (cf. Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024). This leads to our first hypothesis:

H1: Civil servants’ perception that democratic backsliding is occurring is associated with a stronger intention to exit the civil service, and a weaker intention to exercise their voice and exert effort at work.

Additionally, we expect civil servants’ divergent perceptions of democratic backsliding to further shape their inclination to exit, exercise their voice, and work hard by influencing their projections of how much political principals will politicize the bureaucracy, and how much policy influence bureaucrats will have in the future. In regard to politicization, we assume that civil servants are generally averse to unmeritocratic selection and promotion based on either partisanship (Kim, Jung, and Kim Reference Kim, Jung and Kim2022) or cronyism (Shaheen, Bashir, and Khan Reference Shaheen, Bashir and Khan2017). Still, we expect that bureaucrats’ polarized perceptions of democratic backsliding prompt them to hold divergent views and expectations about the degree of civil service politicization, and thereby to vary in their willingness to contribute.

Civil servants who support authoritarian populist leaders and their policies, and reject claims that they are a threat to democracy, are psychologically motivated to believe that the approach of these principals to bureaucratic appointments and promotions would be as meritocratic as, or more meritocratic than, that of their predecessors. Additionally, they may accept the claims of authoritarian populists that the existing civil service is biased against them, and that political intervention in the recruitment and promotion of worthy loyalists is needed. Furthermore, as loyalists, these civil servants have less to fear and lose from politicization. Rather, they may perceive this as an opportunity for advancement. Conversely, civil servants who perceive the policies and actions of political principals to be attacks on democracy likely expect these attacks to coincide with detrimental consequences for the bureaucracy, including its politicization. This in turn is likely to reduce their willingness to contribute due to their expectations of poor organizational performance (e.g., Gallo and Lewis Reference Gallo and Lewis2012), corruption (e.g., Charron et al. Reference Charron, Dahlström, Fazekas and Lapuente2017; Dahlström, Lapuente, and Teorell Reference Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell2012), and harm to their prospects for promotion.

We thus hypothesize that civil servants’ divergent expectations of future politicization mediate the relationship between their perceptions of democratic backsliding and their willingness to contribute:

H2: Civil servants’ expectation of an increase in politicization mediates the associations between perceived democratic backsliding, a stronger intention to exit the civil service, and a weaker intention to exercise their voice and exert effort at work.

Furthermore, analytical and empirical studies suggest civil servants’ willingness to contribute is shaped by the extent to which they enjoy discretion, autonomy, and influence over government policy (Bertelli and Lewis Reference Bertelli and Lewis2012; Gailmard and Patty Reference Gailmard and Patty2007; Richardson Reference Richardson2019). Underlying this relationship are the intrinsic rewards that public-spirited civil servants derive from advancing organizational missions and goals to which they are normatively committed (Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990), and the positive self-esteem that is associated with such influence (e.g., Bertelli Reference Bertelli2007; Brehm and Gates Reference Brehm and Gates1997; Cho and Lewis Reference Cho and Lewis2012; Kim, Jung, and Kim Reference Kim, Jung and Kim2022; Richardson Reference Richardson2019).

In countries undergoing democratic backsliding, civil servants likely hold divergent expectations regarding their future capacity to promote and protect their organizational and individual policy preferences. Those who perceive the actions of political principals to be a risk to democracy will anticipate a harmful loss of policy discretion, and will expect that they will be sidelined and relegated to noninfluential positions (e.g., Dussauge‑Laguna Reference Dussauge-Laguna2022; González-Vázquez, Nieto‐Morales, and Peeters Reference González-Vázquez, Nieto‐Morales and Peeters2024; Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024; Moynihan Reference Moynihan2022a; Peters and Pierre Reference Peters and Pierre2019). Such expectations may prompt civil servants to reduce their intended contributions, leading them to resign (cf., Bolton, Figueiredo, and Lewis Reference Bolton, de Figueiredo and Lewis2021; Dahlström and Holmgren Reference Dahlström and Holmgren2019; Doherty, Lewis, and Limbocker Reference Doherty, Lewis and Limbocker2019a; Reference Doherty, Lewis and Limbocker2019b) or reduce their engagement (Lotta, Tavares, and Story Reference Lotta, Tavares and Story2024). Conversely, loyalists are likely to expect their policy influence to not change or increase, and they may anticipate that future organizational policy will match their values.

Thus, we expect civil servants’ expectations regarding their influence over policy in the future to mediate the relationship between their perceptions of democratic backsliding and their willingness to contribute:

H3: Civil servants’ expectation of a decline in policy influence mediates the associations between perceived democratic backsliding, a stronger intention to exit the civil service, and a weaker intention to exercise their voice and exert effort at work.

The Israeli Case

We examine the above hypotheses in the context of the 37th Israeli government’s advancement of the legal overhaul. This government coalition, sworn in on December 29, 2022, included the Likud, by then a right-wing populist party (Gidron Reference Gidron2023), the ultra-Orthodox parties Shas and Yahadut Hatora, the radical-right Religious Zionist party, and the populist radical-right Otzma Yehudit party.

Five days after the government’s inauguration, Minister of Justice Yariv Levin (Likud) presented the legal overhaul (officially termed “the legal reform”). In a similar vein to other global instances of executive aggrandizement, the legal overhaul involved dismantling checks and balances on the political power of the executive. Its aims included limiting the power of the Supreme Court by altering the power balance within the Judicial Selection Committee, allowing the Knesset to reenact legislation ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and diminishing the Court’s capacity to strike down executive decisions. It further included a proposal to replace career civil servants in legal positions across government with political appointees.

The announcement of the legal overhaul, which took Israelis by surprise, sparked mass antigovernment demonstrations, along with counterdemonstrations supporting the government’s reform (Berman and Staff Reference Berman and Staff2023; Ynet News 2023). Among Israeli Jews, judgments of the legal overhaul strongly correlated with support for the two political blocs (Gidron et al., Reference Gidron, Margalit, Sheffer and Yakirforthcoming) and with levels of religiosity, which are strongly intercorrelated (Arian and Shamir Reference Arian and Shamir2008). Supporters of the opposition, mostly secular Jews, tended to oppose the legal overhaul. Coalition supporters who endorsed the legal overhaul were mainly religious and ultra-Orthodox Jews voting for the ultra-Orthodox parties (Shas and Yahadut Hatora) and for the Religious Zionist party or Otzma Yehudit, and Likud voters who are mostly “traditional-nonreligious” and “traditional-religious.” Women were also inclined to oppose the legal overhaul. Subsection A1.1 of the online appendix provides evidence for the associations between Israeli citizens’ religiosity, gender, and partisan identity, and their support for the legal overhaul.

The 37th government’s advancement of the legal overhaul continued a long-term populist shift in Israeli politics (Levi and Agmon Reference Levi and Agmon2021). This shift coincided with the dominance of Benjamin Netanyahu as prime minister in 12 out of the 13 and a half years preceding the formation of the 37th government. During this period, levels of affective polarization among Israelis increased by 180% (Amitai, Gidron, and Yair Reference Amitai, Gidron, Yair, Rahat, Gidron and Shamir2025; Gidron, Sheffer, and Mor Reference Gidron, Sheffer and Mor2022). Soaring polarization was partly associated with Netanyahu’s 2019 bribery indictment and his refusal to step down, instigating political instability and five successive elections between 2019 and 2022. In response, the electorate’s identification congealed into two distinct party blocs consisting of Netanyahu’s supporters and his opponents (Gidron and Sheffer Reference Gidron and Sheffer2024).

The political turmoil that preceded the formation of the 37th government adversely affected the Israeli civil service. Bureaucratic performance, reputation, and quality were undermined by a two-year budget freeze (2019–20), intensified conflicts between political elites and civil servants, and heightened politicization (Cohen, Duhl, and Abutbul Reference Cohen, Duhl and Abutbul2024). These processes exacerbated the Israeli bureaucracy’s mediocre meritocratic quality (ranked 25th out of 33 OECD countries in the 2015 Gothenburg Quality of Government expert survey). This meant that the Israeli bureaucracy encountered the attack of the 37th government in a weakened position, potentially rendering civil servants more amenable to normalizing the risks of democratic backsliding.

Methods

To examine Israeli civil servants’ perceptions of the legal overhaul and their willingness to contribute, we employ a mixed-methods design. We preregistered our hypotheses and empirical design.Footnote 1 The study received ethical approval from the Social Science Ethics Committee of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

In February and March 2023, we conducted an anonymized online survey among Israeli civil servants. The survey’s early timing, about a month and a half after the government’s inauguration and its unexpected announcement of the legal overhaul, meant that it gauged civil servants’ perceptions and planned intentions before the latter could realistically materialize. Additionally, at this stage, the coalition prioritized the legal overhaul as its key, if not sole, agenda. Therefore, respondents’ planned intentions were plausibly unaffected by other policy initiatives. Furthermore, our respondents, as career civil servants, had served under previous coalitions headed by Netanyahu, many of which included right-wing conservative and populist ministers. Consequently, if our hypotheses are confirmed, it is likely attributable to civil servants’ responses to the government’s advancement of the legal overhaul, over and above the coalition’s composition or ideology.

Still, the survey’s observational and cross-sectional nature limits our ability to make causal claims. To unpack the causal mechanisms underlying respondents’ answers, we invited them to add open-ended comments eight times during the survey. Additionally, we carried out semistructured interviews (March–April 2023) with survey participants who left us their emails for further research, as well as a focus group (May 2023). Finally, in May 2024, we approached the participants who left us their emails with a short follow-up survey to gauge the association between their planned intentions and subsequent actions.

Lastly, we note that we intentionally refrained from asking our respondents, who are all government employees, which party they voted for. We expected Israeli civil servants to consider such a question inappropriate and sensitive even when promised anonymity. Instead, we asked survey respondents about their level of religiosity, which, as explained above, is a close proxy for Jewish Israelis’ support for the coalition and opposition blocs.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Survey Sample and Procedure

Given the politically sensitive nature of the study, we could not distribute the survey via official government channels. To maximize the sample’s size and diversity, we distributed the survey through multiple channels—including the public policy schools of three universities, which sent it to their current and former students; civil servants’ networks; personal connections; and social media channels—and by asking participants to distribute the survey link to their colleagues. To mitigate selection bias due to partisan identity or the contentious nature of the legal overhaul, we emphasized the survey’s anonymity and phrased the invitation, instructions, and items in a normatively neutral manner (e.g., using phrases such as “the changes that are being advanced these days concerning the legal system and the civil service”). See section A2 of the online appendix for an elaboration of the survey’s distribution and its structure.

The survey was conducted between February 16 and March 7, 2023, alongside the parliamentary discussions of the legal overhaul bills and the mass protests. Overall, 954 potential respondents opened the survey link, of whom 684 indicated that they currently worked in central government, and 465 respondents answered at least one of our three outcome variable questions. Since graduates of public policy MA programs were among our main targets, the study was bound to better represent mid- and senior-level employees in policy-related positions over junior and frontline bureaucrats. Moreover, junior civil servants, who have limited interactions with politicians, are plausibly less affected by the early stages of democratic backsliding. We therefore excluded 71 participants who categorized themselves as juniors (although including these participants does not alter our findings). Thus, our sample consists of 394 respondents from 27 ministries who self-categorized their ranking as middle (n = 213), senior (n = 127), or very senior (n = 22), and additional participants (n = 32) who did not answer the subjective ranking question.

Table 1 compares the demographics of our sample to the population of middle and senior civil servants based on data we obtained from the Civil Service Commission. The comparison suggests our sample overrepresents younger employees, those with a tenure of up to 10 years, the highly educated, and the more senior, and underrepresents those with a legal background. Also, only four Israeli-Palestinians responded, causing our sample to underrepresent a group that is already poorly represented in the civil service. These imbalances imperil the generalizability of our findings to the civil service population. Specifically, extrapolating from citizen surveys (table A1.1 in the online appendix), the overrepresentation of highly educated civil servants likely entails that our sample overrepresents supporters of the opposition parties, who disapprove of the legal overhaul.Footnote 2 Moreover, the overrepresentation of senior civil servants may make our respondents more likely to leave if they expect their policy influence to be curbed (cf. Bolton, Figueiredo, and Lewis Reference Bolton, de Figueiredo and Lewis2021). As detailed below, we mitigate these concerns by testing the robustness of our findings to survey weights and relevant covariates, with no meaningful changes to the main results.

Table 1 Characteristics of the Survey Sample and Research Population

Notes: Valid percentages are reported (excluding missing values). The research population data, obtained from the Civil Service Commission, pertain to civil servants across central government ministries and their subunits who are officially categorized as “social scientists” or “legal professionals.”

Operationalization of Variables

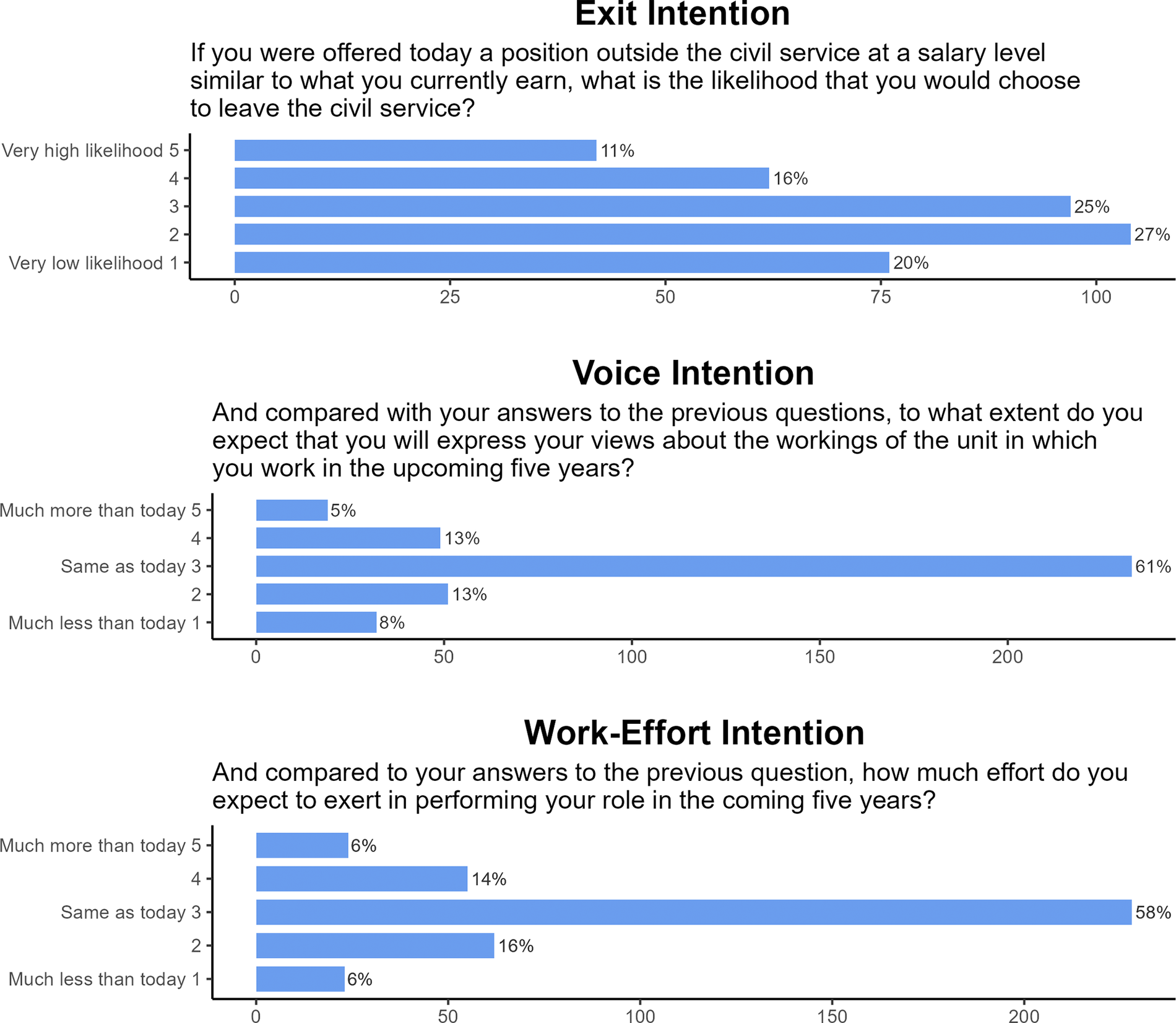

To capture civil servants’ willingness to contribute, we estimate three outcome variables. First, to measure exit intention, we asked respondents, “If you were offered today a position outside the civil service at a salary level similar to what you currently earn, what is the likelihood that you would choose to leave the civil service?” (a five-point scale, from “very low” to “very high”).Footnote 3 Second, to measure respondents’ voice intention, we first asked them about their voice behavior in the past five years (past voice), a control variable consisting of three Likert-scale items borrowed from Van Dyne and LePine (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.975). Then, gauging respondents’ projections, we asked, “And compared to your answers to the previous question, to what extent do you expect that you will express your views about the workings of the unit in which you work in the upcoming five years?” (a five-point scale, ranging from “much less” to “much more”). Third, to gauge respondents’ work-effort intention, we first asked, using one item, about their past exertion of effort at work (past efforts), which we employ as a control variable, and then about their projected effort using the following question: “Compared to your answer to the previous question, how much effort do you expect to exert in performing your role in the coming five years?” (a five-point scale, ranging from “much less than today” to “much more than today”).

To estimate the main explanatory variable, civil servants’ perceptions of democratic backsliding (perceived democratic backsliding), we use six items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.968) couched “against the background of the advanced changes in the legal system and the civil service.” Participants first answered a general sentiment question: “How do you feel about the state of Israel’s democracy in the foreseeable future?” Responses ranged from “very pessimistic” (= 1) to “very optimistic” (= 4), and were reverse coded so that higher values signify greater pessimism.Footnote 4 Then, to avoid directly asking civil servants for their views on the politically contentious legal overhaul, and consistent with our theorization that positions on salient political debates are shaped by individuals’ social embeddedness in rival political camps, we asked them whether their family members and close friends perceived “the changes that are being advanced” as malign or benign to Israel’s democracy. We designed the content of the items to reflect the polarized discourse surrounding the legal overhaul, with five seven-point Likert-scale items ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Two representative items are “My family and close friends believe that Israel’s democracy is in real danger,” and “My family and close friends believe that the Legal Reform will strengthen democracy” (reversed). Confirmatory factor analysis confirms that all six items load on one latent variable (factor loading ranging from 0.83 to 0.97).

To measure the mediating variables—expected changes to policy influence (expected influence) and politicization (expected politicization)—we first asked respondents about their perceptions regarding the past five years using three items for each variable (past influence and past politicization, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.844 and 0.938, respectively). We then asked about their future projections. Regarding expected influence, we asked, “Looking ahead to the next five years, to what extent do you anticipate that there will be an increase or waning in the degree of influence that the professional ranks in your unit exert over the ministry’s policies within the unit’s remit?” (ranging from “substantial waning” [= 1] to “substantial increase” [= 5]). As for expected politicization, we asked, “And looking ahead to the next five years, to what extent do you anticipate that there will be a change for the better or for worse in the extent to which promotions in the department will de facto be made based on relevant experience, competence, and hard work?” (ranging from “substantial change for the worse” [= 1] to “substantial change for the better” [= 5]). In the analysis, we reverse coded the latter item so that higher values represent greater concerns of unmeritocratic (i.e., politicized) promotions.

Lastly, as control variables, we collected information on respondents’ demographics (gender, age, nationality, education, and religiosity), and professional characteristics (tenure, type of appointment, subjective seniority, and departmental affiliation). We also coded the political party of the minister responsible for their ministry.

Section A3 of the online appendix presents the full list of variables and their wording. To facilitate the interpretation of our findings, we transformed all variables to vary from zero to one.

Measurement Bias and Validity

Two concerns merit discussion before proceeding to the results. First, we sought to mitigate “partisan cheerleading” (Bullock and Lenz Reference Bullock and Lenz2019)—that is, insincere responses due to partisan loyalty—contaminating the validity of our measurement. To do so, we offered respondents the opportunity to add open-ended comments before and after each set of items, including the outcome variables, allowing them to express their detailed opinions and to “blow off steam” (Yair and Huber Reference Yair and Huber2020). A total of 183 of 394 respondents added open-ended comments.Footnote 5 The number and content of these comments also alleviate concerns about “cheap talk,” since respondents’ answers reflected high engagement and genuine concerns. Moreover, 15 months after the distribution of the original survey, in May 2024, we contacted the 50 mid- and senior-level respondents who originally provided us with their emails. In this follow-up survey, we asked respondents whether they still worked in the central government, had left, or had actively sought work outside government in the past year (reported exit behavior). We also asked them to explain, using free-text comments, their reasons for staying or leaving. A total of 43 respondents completed the follow-up survey. We found no statistically significant differences between these respondents and our original sample. Although based on a small and limited subsample, the correlation between respondents’ reporting of exit intent in February–March 2023 and their actual exit in May 2024 (Spearman’s rho = 0.449, p < 0.01) tentatively validates the authenticity of respondents’ original answers. To illustrate this correlation, seven of 10 respondents who originally expressed a high or very high intent to leave the civil service reported exit behavior in the follow-up survey. In contrast, only five of the 21 respondents who expressed a low or very low exit intent reported exit behavior in the follow-up survey. The results are elaborated in section A14 of the online appendix.

Second, since our explanatory and outcome variables are self-reported and measured in the same survey, we risk spurious correlations due to common method variance (CMV). To mitigate CMV we deliberately used different scales and labels for our explanatory and outcome variables, and we also included a designated marker variable (Simmering et al. Reference Simmering, Fuller, Richardson, Ocal and Atinc2015; Williams, Hartman, and Cavazotte Reference Williams, Hartman and Cavazotte2010). For further discussion of how we address CMV, see section A9 of the online appendix.

Statistical Results

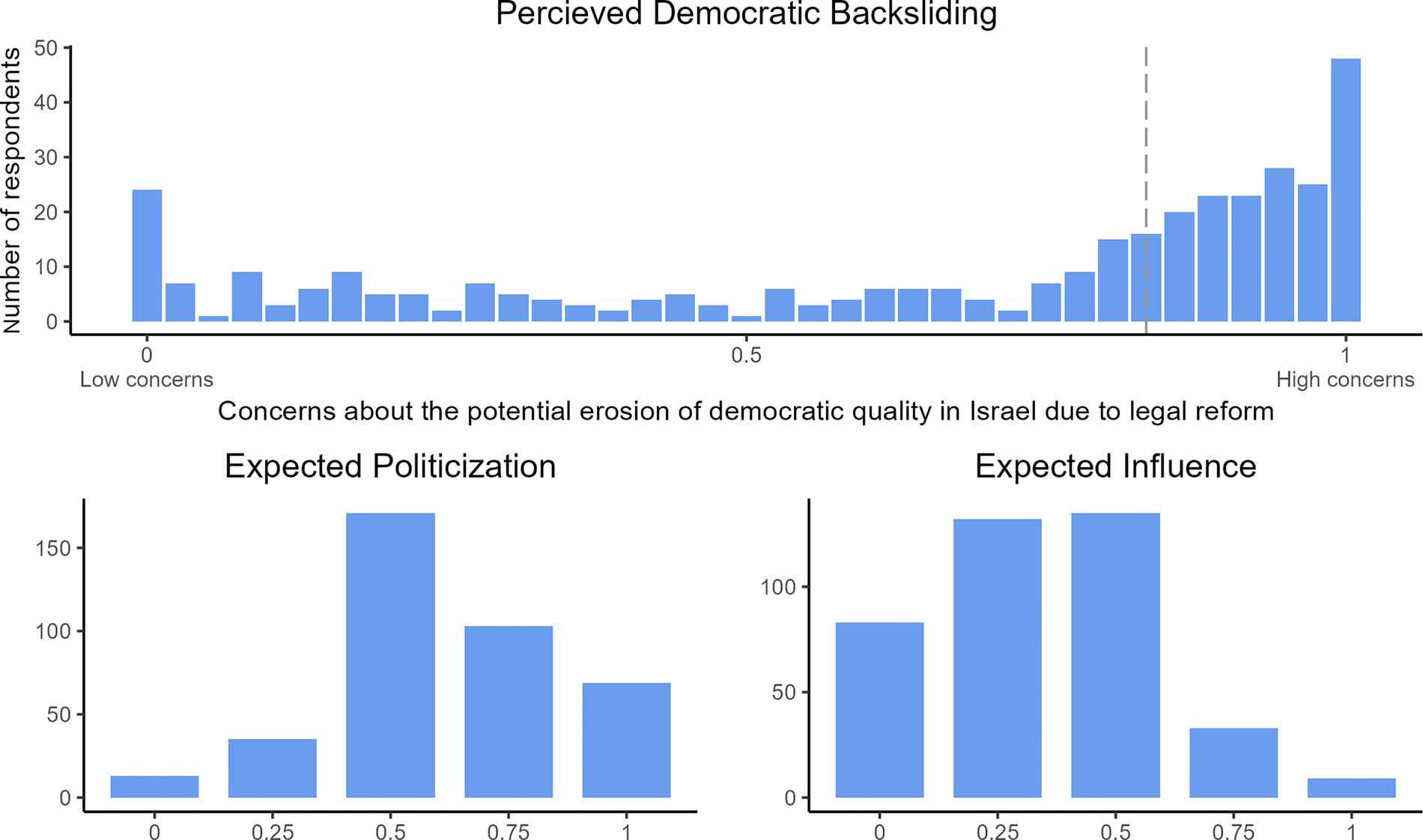

The upper panel of figure 1 presents respondents’ perceptions of democratic backsliding, which are distributed across the variable’s continuum—although most view the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy. We theorized that variation in civil servants’ perceptions of democratic backsliding likely reflects their social embeddedness among rival political camps. Section A5 of the online appendix confirms this assumption, showing that civil servants’ perceptions of democratic backsliding decrease with religiosity levels and are higher among women. Religiosity levels and gender account for 46.5% of the variance in perceived democratic backsliding. These findings replicate the patterns among Israeli citizens (see the Israeli Case section above, and subsection A1.1 of the online appendix).

Figure 1 Distribution of Independent Variables

The distributions of the two mediators (expected politicization and expected influence), in the lower two panels of figure 1, indicate that participants were most concerned about a future decline in their professional influence, although many participants were also worried about increased politicization. The bivariate correlations in table 2 show that perceived democratic backsliding correlates with the two mediating variables and the mediators are intercorrelated.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Notes: Listwise-deletion Pearson correlation coefficients are presented. Correlation coefficients greater than 0.12 are statistically significant.

The distributions of the outcome variables are presented in figure 2. We observe considerable variation in respondents’ intentions to exit. Regarding projected voice and work-effort intention, around 60% of respondents selected the midpoint, meaning they mostly expected no change compared to previous years.

Figure 2 Distribution of Three Outcome Variables

In line with H1, we expect respondents’ perceptions that democratic backsliding is occurring to engender enhanced exit intentions, and reduce voice and work-effort intentions. Additionally, we hypothesize that these links are mediated by respondents’ expectations regarding politicization (H2) and influence (H3).

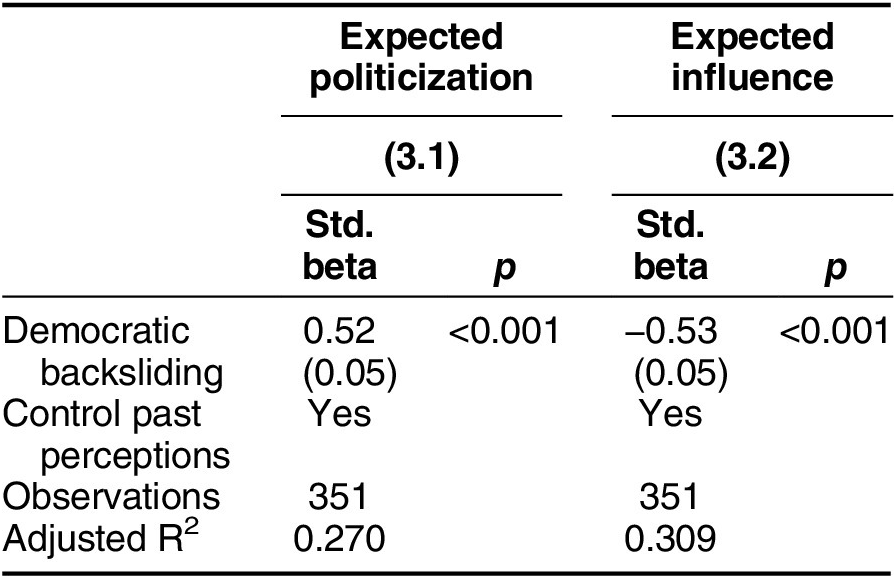

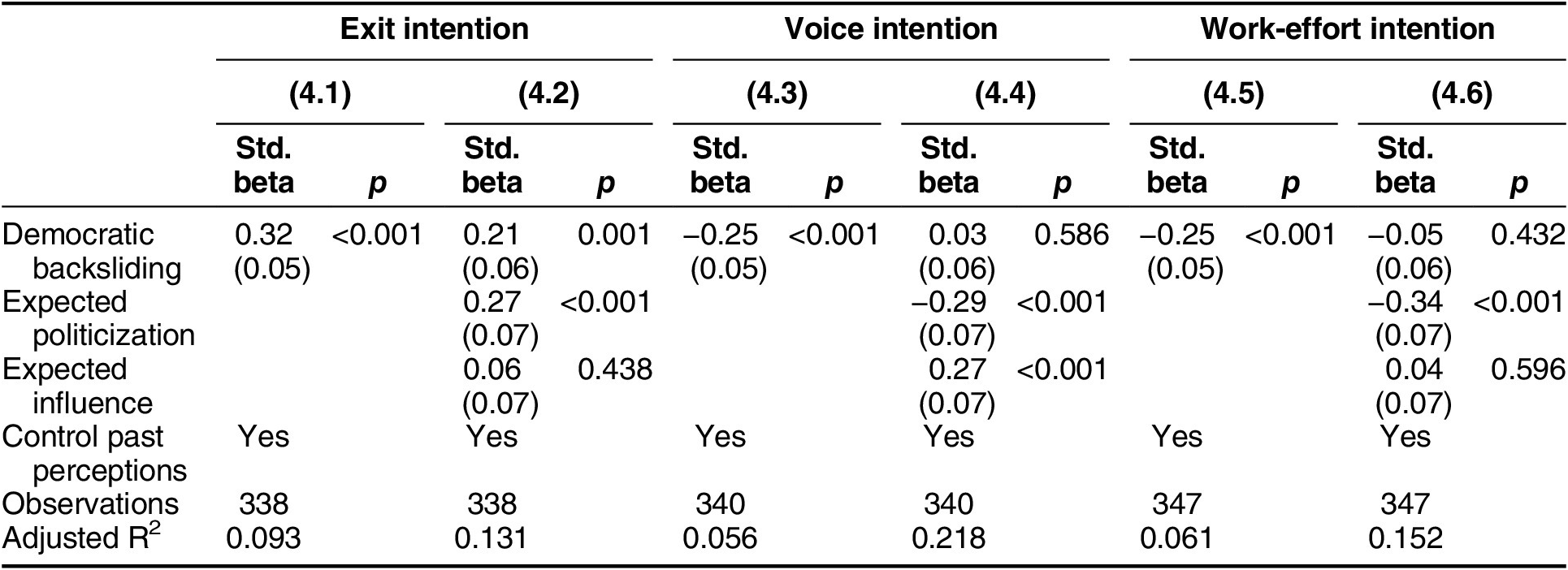

To test these hypotheses, we estimate linear ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models.Footnote 6 Table 3 presents the results of models regressing the two mediators on the main predictor, perceived democratic backsliding. Table 4 examines respondents’ exit, voice, and work intentions, estimating two models for each outcome variable. To assess H1, we regress the three outcome variables on perceived democratic backsliding (models 4.1, 4.3, 4.5). Then, to examine H2 and H3, we fit models that add the two mediators, expected politicization and expected influence (models 4.2, 4.4, 4.6). We control for respondents’ past perceptions of politicization and policy influence in all statistical models. We do so assuming these past perceptions shape respondents’ expectations of future politicization and policy influence (the mediators), and their perceptions of democratic backsliding (the independent variable), rendering them potential confounders in models estimating the mediating variables and the outcome variables (Pearl and Mackenzie Reference Pearl and Mackenzie2018).

Table 3 Regression Models for the Link Between Perceived Democratic Backsliding, Concerns of Increased Politicization, and Reduced Professional Influence

Table 4 Regression Models for the Link Between Perceived Democratic Backsliding, Stronger Exit Intention, and Weaker Voice and Work-Effort Intention

To assess the statistical significance of the mediation of democratic backsliding through each path, we employ bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals and p-values, estimated via structural equation modeling (SEM) using the R lavaan package (Rosseel Reference Rosseel2012). SEM estimates the relationships between observed indicators and latent variables, and the direct and indirect effects between independent and outcome variables within a single model (Kline Reference Kline2016). It allows simultaneous estimation of multiple mediation paths, and accounts for correlations between the mediators (Preacher and Hayes Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). In our case, with two correlated mediators (expected politicization and expected influence), this approach allows simultaneous estimation of the two mediated effects and their significance. Table 5 summarizes the magnitude and significance of the indirect correlation through each mediator. We report standardized beta coefficients and two-tailed p-values.

Table 5 Mediation Estimates

Note: Mediation estimates and bootstrapped 95% confidence interval and p-values estimated via structural equation modeling using the R lavaan package.

For simplicity and due to missing values across the controls, our main models, as presented here, control only for respondents’ perceptions about the past (not reported). Complete versions of tables 3, 4, and 5 (including the SEM results and fit statistics) are presented in section A7 of the online appendix. The measurement-model component of the SEM results is reported in online appendix section A6. Robust analyses and supplementary models are discussed further below.

Squarely confirming H1, perceived democratic backsliding is significantly associated with an enhanced intention to exit (beta = 0.32 [0.21, 0.42], model 4.1), and a reduced intention to exercise voice (beta = −0.25 [−0.08, −0.33], model 4.3) and exert effort at work (beta = −0.25 [−0.14, −0.35], model 4.5). To descriptively illustrate these associations, participants with perceived democratic backsliding scores above the median (0.833) were 80% more likely to express a high intent to leave the civil service (36% versus 20%). They were also 60% less likely to believe they would exercise their voice and exert effort working (17% versus 28% for both variables).

Turning to the mediation hypotheses (H2 and H3), table 3 shows that perceived democratic backsliding is positively correlated with expected politicization (beta = 0.52 [0.43, 0.61], model 3.1) and negatively correlated with expected influence (beta = −0.53 [−0.44, −0.61], model 3.2). In models 4.2, 4.4, and 4.6 in table 4, we examine the associations of the mediators and the outcome variables and assess changes in the estimates of perceived democratic backsliding when adding the mediators to the regression models. Regarding exit intention, model 4.2 shows that when the two mediating variables are included in the regression model, the standardized beta coefficient of perceived democratic backsliding is 0.21 (0.08, 0.33) (p < 0.001) compared with 0.32 (0.21, 0.42) in model 4.1. The coefficient of expected politicization is positive and significant (p < 0.001), while the coefficient of expected influence is insignificant. Compatibly, the mediation estimates (table 5) are statistically significant for expected politicization, and insignificant for expected influence. These findings suggest that civil servants’ concerns about exacerbated politicization (H2), but not those regarding curbed policy influence (H3), partially underlie the positive association between their perceptions of democratic backsliding and the desire to exit.

As to voice intention, model 4.4 shows that when expected politicization and expected influence are included in the regression, both coefficients are statistically significant, and the coefficient for perceived democratic backsliding becomes insignificant. The estimated mediation links (table 5) are both statistically significant at the 95% level. This indicates that the two mediation pathways via expected politicization (H2) and expected influence (H3) underlie the negative association between perceived democratic backsliding and voice intention.

Regarding work-effort intention, model 4.6 shows that when expected politicization and expected influence are included in the regression, the estimate for perceived democratic backsliding becomes statistically insignificant. The findings from the SEM model, as summarized in table 5, suggest that mediation through expected politicization is statistically significant, while mediation through expected influence is statistically insignificant. This indicates that perceived democratic backsliding negatively affects work-effort intention through expected politicization (H2), but not through expected influence (H3).

In section A8 of the online appendix, we confirm the robustness of the findings in tables 3 and 4 through the addition of individual-level controls (appendix subsection A8.1), the inclusion of junior bureaucrats (appendix subsection A8.2), the deployment of regressions with survey weights (appendix subsection A8.3), and exclusion of the controls of respondents’ perceptions about the past (appendix subsection A8.4). Additionally, we explore possible heterogeneous effects of perceived democratic backsliding across respondents’ individual-level traits (appendix subsections A10.1–A10.6) with null findings. We also examine heterogeneity in civil servants’ planned responses given the party affiliations of their ministers (appendix subsection A10.7), and find minor indicative confirmation, with no change to our main results. Lastly, our findings hold with an alternative operationalization of exit intention (appendix section A13). The data and codes for all statistical analyses presented in this section and the online appendix are available for replication (Alon-Barkat et al. Reference Alon-Barkat, Gilad, Kosti and Shpaizman2025).

In summary, within the acknowledged constraints of any observational data and of our sample, we can reject the null hypothesis regarding H1 (perceived democratic backsliding) and H2 (expected politicization as a mediator). As for H3 (expected influence as a mediator), we find mixed findings across the outcome variables.

Qualitative Analysis

To complement the quantitative findings and to partially unpack the causal mechanisms underlying the above statistical results, we draw on three qualitative data sources: free-text comments in the first survey (n = 183) and the follow-up survey (n = 9), in-depth semistructured interviews (n = 20; March–April 2023), and a focus group with five participants (May 2023).

Employing these multiple sources allows us to maximize the breadth of succinct perceptions in survey comments, alongside the depth of interviews and focus groups (Seawright Reference Seawright2016). Those who added comments to the survey were not required to relinquish their anonymity. They represent an array of legal overhaul supporters, opponents, and those who were ambivalent. Comparing the demographics of survey participants who added comments and those who did not, we find no statistically significant differences (see section A11 of the online appendix). Conversely, interviewees and focus group participants cannot represent the full survey sample. They are a small, self-selected group of civil servants who were motivated to discuss their perceptions and concerns regarding a politically contentious event as it was still unfolding. Most opposed the legal overhaul, and some were ambivalent. Interviewees left us their emails and responded to our follow-up invitation. Focus group participants are graduates of a prestigious civil service program who responded to an invitation we sent to all members of this group (and all alluded to having participated in our anonymous survey). We sought participants from this group since membership in the same graduate program allows them to feel comfortable expressing and exchanging views on a highly sensitive issue.

The data from the above three sources were analyzed by employing a flexible coding method (Deterding and Waters Reference Deterding and Waters2021) using MAXQDA software. The initial set of codes was drawn from the theoretical model, including categories regarding perceptions of the legal overhaul, expected politicization, expected influence, and planned responses. Additional codes were added inductively.

For a detailed discussion of the qualitative data collection, coding, and analysis, see section A11 of the online appendix.

Diversity in Perceptions of the Legal Overhaul

In line with the quantitative findings, respondents’ free-text comments reveal their diverse perceptions of the legal overhaul as endangering or boosting democracy. Fierce proponents of the legal overhaul reasoned that it would enhance the quality of democracy by diversifying the judiciary and the bureaucracy and enabling majoritarian political control over a hostile bureaucracy.

As civil servants, we experience the rule of the legal advisers [in our ministries] on all policy processes … it is a significant roadblock … there is a need for reform.Footnote 7

I saw with my own eyes how the civil servants hamper the minister’s plans in every possible way—starting from legitimate persuasion through … tricks, misleads and leaks [to the press] … the minister has little power when facing the civil servants, which requires a change.Footnote 8

Others, representing ambivalence, suggested that the danger of the legal overhaul, insofar as the bureaucracy is concerned, is exaggerated, because the civil service has experienced politicization for several years, and ministers trying to promote unprincipled policy is nothing new. Therefore, these respondents were either more concerned with the present situation than with the future perils of the legal overhaul or believed that they would overcome the current danger in a similar vein to prior challenges. Others stated that although they object to the legal overhaul, they do not think it would affect their work, because their autonomous units are exposed to limited, if any, politicization—a view that with hindsight turned out to be wrong.

The rest of the analysis focuses on those respondents who perceived the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy, who are the majority of our sample. Whether referring to themselves or to colleagues in their department or in other ministries, the theme of leaving the civil service is prominent among these respondents. Below we analyze their concerns and explanations for why they or others might leave.

Expected Politicization

Mirroring the quantitative analysis, respondents perceived politicization as an ongoing problem, which they expected to exacerbate in the aftermath of the legal overhaul. They conceived of politicization as a personal threat to their career prospects and to those of other civil servants, and as a systemic threat to the civil service.

Respondents expressed their concerns that the selection and promotion of managers and employees would increasingly be based on their political affinity and personal loyalty to the minister over competence and expertise. They believed that, as a result, competent job seekers would not apply for civil service jobs. Likewise, they, and others, would leave because they would not want to work with unqualified colleagues, or because they would be unfairly passed over for promotion. Female respondents were particularly concerned about their own and other women’s prospects under the new regime.

As the culture of power and [political] bias … will increase, those promoted to the highest ranks will be the less fit—people who cannot withstand political pressure and those with low self-esteem. Clearly, good people, professionals, and there are many such people in the ministry, are not interested in being promoted [since this would expose them to direct political pressure]. … [F]ewer women will present their candidacy for these positions.Footnote 9

Moreover, respondents were concerned that widespread politicization would change the essence of government work from a public service into a political machine. They reasoned that with increasing politicization, career civil servants would be suspected by politicians, who would mark everyone based on their partisan loyalty, and superiors would not back them up since they would be loyal to the minister. Eventually, the loyalty of civil servants would be to politicians’ personal and electoral interests rather than to the interests of the public. This would further increase the exit of dedicated public servants. The following interviewee summarizes these concerns:

Once all the senior positions are patronage-based, there will be no professionalism. This, in turn, means that you have no promotion prospects as an employee, and … that you cannot trust that the deputy director general [who is supposed to be politically neutral] is guided by professional considerations because he is committed to a political camp, and this makes all the senior managers in the office into a branch of the coalition. This is not a good, trustworthy, and pleasant environment where you can come home at the end of the day and say I did something good. People want to … feel that they serve the public, not Bibi [the prime minister] or Lapid [the opposition leader]. Today, politicization is trickling down and affecting this feeling.Footnote 10

Expectation of Decreased Policy Influence

The quantitative data analysis suggests that civil servants who perceived the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy expected a future decrease in their policy influence; yet, once accounting for expected politicization, expected influence does not predict their exit intentions. The qualitative analysis, conversely, indicates that concerns about losing influence were not only salient but loomed large in respondents’ thoughts about leaving.

When asked what value they see in working in the civil service, interviewees almost unanimously mentioned their ability to influence policy and participate in important decisions that advance the public interest. A recurrent concern of the participants was that the legal overhaul would undermine their ability to influence policy and make a difference. This issue received the highest number of free-text survey comments (n = 65). Respondents’ concerns that politicians would discard their advice and expertise were not mere projections. They reflected ministers’ and coalition backbenchers’ pejorative reference to them as “bureaucrats” as opposed to “experts.” Moreover, respondents felt that more than ever before, politicians distrusted them and did not see them as “playing on the same team.” This further contributed to respondents’ fear that politicians are likely to constrain their autonomy:

There is this vibe with the [legal overhaul] reform that says we do not believe anybody unless he is with us.Footnote 11

Ultimately, signals of politicians’ disrespect for expertise and distrust in career civil servants incited respondents’ fears that they would be prevented from using their knowledge and expertise to influence policy, relegating them to mere technicians:

If these laws [of the legal overhaul] pass, people would not stay and work. … They will feel their opinion is undervalued and meaningless, and then you become a technician. We [in the legal department] … will become just drafters [of legislation]. They [the politicians] tell us to draft legislation, and then [currently] we say that we have some comments, but if we believe that they will not accept our comments, then our job is only technical.Footnote 12

Threat to Civil Servants’ Identity as Guardians of the Public Interest

Transcending the focus of the quantitative data analysis on politicization and curbed policy influence, our qualitative data sources and analysis uncovered respondents’ experience of the legal overhaul as an overarching threat to the fundamental meaning they attached to their role as civil servants. As elsewhere (cf. De Graaf Reference De Graaf2011; Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990; Selden et al. Reference Selden, Brewer and Brudney1999), Israeli civil servants tend to perceive themselves as guardians of the public’s interest (Gilad and Alon-Barkat Reference Gilad and Alon‐Barkat2018). Consequently, those who perceived the legal overhaul as a threat to Israel’s democracy were anxious of being personally or collectively associated with the execution of acts by a nondemocratic regime that would harm its citizens. Given their self-concept as guardians of the public and its interests, respondents were concerned that if politicians dismantled democracy and pursued policies incompatible with the public’s interest, they would be accomplices against their volition.

I do not want to be part of a government that hurts the citizens.Footnote 13

For me … the Zionist vision is a democratic country. … If this … collapses, and somebody wants this country to be just Jewish, then it would no longer be a democracy … so one of the issues … is that the civil service [in such a context] … will partake in the exploitation of public resources to the benefit of one segment of the public over others … and then, I don’t want to be part of this … and maybe not an Israeli citizen either.Footnote 14

Consequently, they felt a loss of pride in working for the government and were reluctant to recommend others to join the civil service.

People might say they do not want to be civil servants anymore … to work for the government or represent the government. If this is where the government is going, I do not want to represent it.Footnote 15

Many respondents specifically raised concerns about politicians’ future pursuit of illegal or immoral policies, exclusively serving their electoral base to the detriment of the general public or minorities. Thus, among respondents’ main concerns was that the legal overhaul would decrease their ability to guard against unprincipled policies, corruption, and the undermining of the public interest. For example:

The thing concerning me the most is that there will be much more corruption. … The [legal overhaul] reform enables political decisions in places where the decisions should be made based on professional considerations or by professionals. For instance, in housing and [land-use] planning. … This will be a disaster.Footnote 16

Our theoretical framework suggests that civil servants’ identity as citizens, who are embedded among rival social camps, shapes their perceptions of democratic backsliding, and, consequently, the extent to which they experience a threat to their professional identity. Confirming this expectation, respondents often referred to the legal overhaul as an intertwined threat to their future as Israeli citizens and to their role as civil servants. Some linked plans to exit the civil service with thoughts about leaving the country. Many expressed anxieties about their children’s future along with worries about the civil service.

I dread this country’s future and the ability of my children to live here in a world that reflects my values. I do not see how we can continue working in the civil service. It feels like I am taking part in something immoral that history will remember for many years.Footnote 17

I am very concerned about the situation in the country. I am planning to leave the civil service in the next year. I wish to give my children a future outside of Israel.Footnote 18

Still, despite these concerns and identity threats, many respondents expressed their intention to stay so long as they believe they are still serving the public interest, and leave if they conclude that their efforts are not enough to overcome the wrongdoing around them. The following quotation summarizes these concerns:

Like many people in this country [I worry about what will happen]. … But … for me and for other people [at the ministry] there is [an additional] question of how it [the legal overhaul] will affect our work. … [T]here are several dimensions here; first, my position, my status: how they [the politicians] are going to see us, and to what extent are they going to listen to us. … If we give our [legal] advice and [it] … will not be binding, what are we there for? What is our role? I also feel that the entire system will be … more politicized and less professional. All this will make many people say, “I do not want to stay in such a situation.” This increases the feeling of depression we feel now and the anxiety that people will leave.Footnote 19

Lastly, the analysis of respondents’ answers to the open-ended questions in the follow-up survey conducted in May 2024 reveals that the threats to their role as civil servants, which respondents alluded to in 2023 as reasons why they might leave, have led some of them to leave or actively seek work outside the civil service. These respondents conveyed that they could no longer serve the public’s interest and felt coerced to serve ministers’ narrow partisan interests. They also alluded to increasing politicization, and to politicians’ disrespect for them as professionals and disregard for professionalism. Consequently, they felt they could no longer influence policy making. The following quotations illustrate these views, echoing respondents’ fears in 2023:

It seems that there is … populism in every corner. The attitude of the politicians is dismissive. Many good civil servants have left, and those who stayed are the minister’s yes-men. The general atmosphere is one of suspicion between employees and distrust between the administrative and the political ranks.Footnote 20

I left the ministry when the policy decisions of the minister radicalized, and I felt that I could no longer back them up. In addition, the radical objection of the minister to any professional stance that does not benefit the preferred faction he wishes to advantage became unbearable. The relations with the political ranks became one of belittling and humiliation.Footnote 21

Summary of Findings

Opening the black box of state bureaucracy, this article demonstrates the divergence in Israeli career civil servants’ perceptions of the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy, and the ramifications for their planned intentions. We show that Israeli civil servants’ perceptions of the legal overhaul reflected their partisan identities as citizens. Furthermore, confirming our hypotheses, respondents who perceived the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy expressed a stronger intention to exit government and weaker commitment to exercise their professional voice and exert effort at work. We also find correlative support for the hypotheses that these patterns are driven by bureaucrats’ projections of increased politicization and curtailment of their policy influence (although the latter mediation effect is inconsistent).

Unpacking the causal mechanisms underlying the above associations, qualitative analysis reveals that civil servants who perceived the legal overhaul as a threat to democracy contemplated leaving due to the overarching threat posed to their professional identity. That is, they experienced a threat to the positive meaning and self-esteem (or pride) they associated with their role as civil servants. Specifically, it was not only exacerbated politicization and curtailed policy influence that concerned them but also the possibility that they would be coerced to partake in, or were already involved in, harming rather than serving the public. This threatened their professional identity and conception of their role as guardians of the public and its interests.

Conclusion

The implications of our findings need to be gauged against recent scholarship suggesting bureaucracy can and should be equipped to buffer authoritarian populists’ attempts to dismantle democracy (e.g., Bauer Reference Bauer2024; Yesilkagit et al. Reference Yesilkagit, Michael Bauer and Pierre2024). Scholars propose that civil servants’ socialization and training, in universities and on the job, should inculcate them with an ethos that they are guardians of liberal democratic institutions and values. This ethos, they argue, should be supported by enhancing the structural independence of bureaucracies and limiting external appointments to senior positions. Confirming the plausibility of this aspiration, our qualitative data, along with prior research, show that civil servants often self-identify as guardians of the public and not as ministers’ obedient servants (De Graaf Reference De Graaf2011; Gilad and Alon-Barkat Reference Gilad and Alon‐Barkat2018; Perry and Wise Reference Perry and Wise1990; Selden et al. Reference Selden, Brewer and Brudney1999), which logically extends to protecting the liberal democratic system. Still, our findings imply that bureaucrats’ likelihood and ability to espouse a role as guardians of liberal democracy is constrained not only by the power of governing politicians but also by the political polarization that often coincides with the decline of democracy (Orhan Reference Orhan2022). As elaborated below, this conclusion carries important implications for scholarly discussions about career civil servants’ role vis-à-vis populism and democratic backsliding.

First, our findings imply that civil servants do not homogeneously seek to protect liberal democracy. Rather, some endorse executive aggrandizement when undertaken by their political camp. We hope this divergence can be attenuated by explicitly socializing and training civil servants to act as guardians of liberal democratic institutions and values. Still, we suspect that once political polarization is underway, and political rivals adhere to competing conceptions of democracy (Grossman et al. Reference Grossman, Kronick, Levendusky and Meredith2022), civil servants will differ in their willingness to accept such a guardianship role, in their interpretation of its meaning, and in their behavior in practice.

Second, our findings imply that civil servants’ social embeddedness in polarized political camps leads them to respond in ways that paradoxically enable the decay of the civil service and the erosion of democracy. Liberal bureaucrats feel most threatened by the potential adversities of democratic backsliding for politicization, professional influence, and their capacity to serve the public. They are thereby more likely to leave at an early stage, before the full realization of these risks. Meanwhile, those who interpret politicians’ actions as legitimate attempts to seize democratic control are inclined to stay because they are optimistic about the future of bureaucracy and democracy. Over time, if authoritarian populists remain in power, this selective exit can result in partisan homogenization of the civil service. This, in turn, may further weaken bureaucratic resistance, and facilitate authoritarian populists’ reliance on a politicized bureaucratic machine to favor their supporters, attack the opposition, and undermine democratic institutions. Political homogenization could also undermine bureaucrats’ inclination and capacity to safeguard civil and human rights and protect vulnerable groups, and specifically immigrants and minorities.

Third, we expect that active guardianship by civil servants who choose to stay in their positions is also hindered by political polarization. Effective bureaucratic gatekeeping requires collegial deliberation and collective action, which get compromised when polarization penetrates the bureaucracy, fostering distrust among civil servants from rival political camps. Moreover, civil servants’ inclination to “speak truth to power,” and the effectiveness of their voice, rests on their public legitimacy as impartial professionals and their reputation for expertise (e.g., Carpenter and Krause Reference Carpenter and Krause2015). In hyperpolarized political contexts, civil servants who voice dissent risk losing professional credibility, as they are distrusted and discredited by politicians, and thus perceived by citizens as politically biased (Alon-Barkat and Busuioc Reference Alon-Barkat and Busuioc2024; Yair Reference Yair2021).

The above findings, implications, and limitations point to several avenues for further research. First, the Israeli civil service ranks relatively highly among OECD countries (although not among non-OECD countries) in terms of politicization, and it has experienced increased politicization in recent years, which may explain respondents’ inclination to reduce their engagement as opposed to fighting back. Future research may examine whether and how prior levels of meritocracy affect civil servants’ responses to democratic backsliding. Second, although our statistical analysis reveals little systematic variation across government departments, we appreciate the need to investigate organization-level factors that boost bureaucratic guardianship. Third, our findings that civil servants’ intentions to leave stem from the threat posed to their professional identity tentatively indicate that liberals may be more likely to stay and fight back if offered validation of the importance of their role and emotional support to neutralize this threat. Such support can emanate from social networks within and outside the public sector. Relatedly, we assume that civil servants who perceive a risk to democracy and, as a result, to their role as civil servants differ in their willingness to stay before these risks materialize into a fully fledged reality of regime change. Thus, an important research avenue would be to understand under what conditions civil servants who perceive a threat to democracy and bureaucracy are inclined to remain in the civil service, and how they cope with the threats to their professional identity. Fourth, extant research on the interface of bureaucracy, populism, and democratic backsliding has mostly limited its gaze to those who already work in government (but see Gilad, Sulitzeanu‐Kenan, and Levi‐Faur Reference Gilad, Sulitzeanu‐Kenan and Levi‐Faur2024). Yet it is no less important to examine how populism and democratic backsliding affect job seekers’ career choices between government, business, and the nonprofit sectors.

In conclusion, this article suggests we cannot make sense of bureaucrats’ responses to democratic backsliding without appreciating their dual identities as government professionals and citizens in polarized political contexts. This entails a better understanding of bureaucrats’ political identities and greater cross-fertilization between studies of bureaucrats’ and citizens’ reactions to the dismantling of democracy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272500074X.

Data replication

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/N7WGRO.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors and four anonymous reviewers for their instructive comments. This article was presented at the 2023 European Group of Public Administration Conference in Zagreb, and at the faculty seminars of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Tel Aviv University political science departments. We thank the participants for their helpful comments. We thank the Hebrew University’s Faculty of Social Science for funding, and the Israeli Civil Service Commission for background data on civil servants’ demographics. We are thankful to Ayala Davidzon, Naama Koreh, and Orpaz Confino for superb research assistance. Above all, we thank the participating public policy schools for their assistance, and numerous civil servants for granting us their invaluable time and insights.