Introduction

This article analyses the use of adversarial questions in oral hearings conducted by the Parole Board for England and Wales (PB). The Board is responsible for making decisions about conditional release from prison for prisoners serving indeterminate and certain determinate sentences (such as terrorist or serious child sexual offences) and re-release of those who have been recalled to prison for breach of licence conditions. The Board makes release decisions by initially examining a dossier that is compiled by His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service to determine whether the test for release—as codified in the Victims and Prisoners Act 2024—is met, and whether fairness would require an oral hearing to be convened. The oral hearing represents an important opportunity for prisoners to give their side of the story and for PB panel members to take oral evidence and question both the witnesses and prisoner to inform their decision.

In deciding whether an oral hearing is required, the PB applies the principles from the Osborn judgment set out by the Supreme Court which emphasise fairness (Osborn vs. Parole Board (2013) UKSC 61). The PB also needs to decide which mode of hearing will be used: in-person, videocall, telephone call, or hybrid. The PB had been moving towards holding more hearings remotely prior to the Covid-19 pandemic which then initiated a swift move towards remote working, with all oral hearings running remotely. This helped avoid a significant backlog of outstanding cases developing—as well as providing increased capacity and flexibility—and the PB has since continued to hold hearings remotely by default, partly because remote hearings mean that further backlogs are less likely to occur. Despite these benefits there are reported problems with remote hearings: PB panel members have pointed to the potential for remote hearings to impede participation for prisoners, create a greater power imbalance between panel members and prisoners, limit prisoners’ access to legal representation, and potentially inhibit participation for prisoners with neurodiversity (Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow and Phillips2023). Prisoners do not typically have a choice over which mode is to be used for their oral hearing—although they can submit representations and explain why a remote hearing prevents a fair hearing—giving rise to potential problems around prisoners’ access to fair justice (Phillips, Peplow, Oliver, & Purnell Reference Phillips, Peplow, Oliver and Purnell2025). The Board has chosen to keep in-person hearings low in number because they deem virtual hearings to be ‘safe and effective’ (Parole Board Reference Parole Board2022:11). Currently, around 93% of hearings are carried out online and 7% are held wholly in-person. Nonetheless, communication differs across modalities, with remote communication posing more challenges than in-person communication because of a lack of physical cues, technological issues, and higher cognitive load (for an overview, see Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow and Phillips2024). In this article we consider the effect that modality has on panel member interactions with prisoners, and specifically whether the questioning of prisoners is more adversarial in remote or in-person hearings.

Through focusing attention on the prisoner’s offending history, their behaviour in custody, and their future risk to the public upon potential release, oral hearing discourse highlights the ‘spoiled identity’ of the prisoner (Lavin-Loucks & Levan 2018). Nonetheless, oral hearings should be inquisitorial and investigative rather than adversarial and oppositional:

Its purpose is elicitation, examination and probing of oral evidence. It should not be characterised by opposition, or the adversarial approach found in criminal courts. However, that does not mean a panel cannot take a more robust approach when applications requiring a decision are made and challenged. (Parole Board Reference Parole Board2023:6)

Our present focus is on occasions where the questioning of prisoners moves into the adversarial, and the distribution of these questions across remote and in-person hearings. To explore this, we focus attention on three distinct forms of question used by panel members:

• Negatively polarized questions (NPQs): e.g. didn’t you think that was a bad idea?

• Why + negative questions (WNQs): e.g. why weren’t you able to stop yourself?

• Statement questions (SQs), with and without tags: e.g. that was a good decision (wasn’t it)?

Specifically, we are interested in the ways in which panel members highlight prisoner accountability through these questions and in the effect, if any, that the mode of hearing has on the production of these challenging questions. Our research questions are therefore as follows:

• What is the relationship between mode of hearing (remote vs. in-person) and the production of adversarial questions?

• How do discourses of blame and responsibility operate in the production of adversarial question types?

Literature review

Video-mediated communication

Verbal, synchronous communication ‘at a distance’ has been possible since the invention of the telephone (Horton & Wohl 1956). The advent of the internet and, subsequently, broadband has allowed videocall communication to become a normal way for individuals to interact remotely. Video-mediated communication (VMC) comprises a ‘distinct and relatively recognizable domain of interaction’ that takes place between people ‘residing in at least two different sites’ (Licoppe Reference Licoppe2021:365). Early research on VMC often pointed to the ‘fragile’ nature of communication in this mode (de Fornel Reference de Fornel1996:53) and the ways in which communication by video created, or exaggerated, power imbalances between participants (Heath & Luff Reference Heath, Luff and Button1993). Technological improvements in the intervening years have reduced these problems to some extent, and VMC was an important way for people to keep some degree of ‘physical’ contact with others during the Covid-19 pandemic (Rouxel & Chandola Reference Rouxel and Chandola2024). Nonetheless, VMC and in-person communication modes have particular ecologies and thus remain distinct from one another. ‘Co-presence’, defined as being ‘close enough to be perceived’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1963:17), is key to in-person interaction, and such ‘mutual monitoring’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1964) is likely to be impeded in remote modes of communication, even those—like VMC—that do provide visual access to interlocutors. However, others have argued that physical co-location is not a prerequisite of ‘co-presence’, and therefore that attention must be paid to the ways that participants in technology-mediated communication perceive ‘entrainment’ with one another, where ‘entrainment’ refers to ‘the synchronization of mutual attention, emotion, and behaviour’ (Campos-Castillo & Hitlin 2013:171). Rossner (Reference Rossner2021), for example, has argued that entrainment is possible in virtual courts (i.e. law courts held over remote links) if participants make allowances for communicational differences between this mode and the in-person mode. Nonetheless, even with developments in technology and the possibility of entrainment between interlocutors, researchers argue that VMC provides a lower quality form of interaction when compared with in-person because participants do not share ‘the same physical space’ (Mlynář, González-Martínez, & Lalanne 2018:78). VMC ‘inherently suffers from some latency’ (Seuren, Wherton, Greenhalgh, & Shaw Reference Seuren, Wherton, Greenhalgh and Shaw2021:64) and remote, online, and digital modes of interaction do not compensate for in-person communication when this is taken away (Rouxel & Chandola Reference Rouxel and Chandola2024). Furthermore, it has been found that interlocutors often blame each other, rather than technology, for these problems in VMC (Schoenenberg, Raake, & Koeppe Reference Schoenenberg, Raake and Koeppe2014). Despite Rossner’s (Reference Rossner2021:361) positive attitude towards virtual courts in general, she argues that in-person hearings should be maintained for ‘complex criminal matters’.

Blame and responsibility in parole hearings

In the field of criminology, analysis has identified a ‘responsibilising’ turn in criminal justice policy and public discourse around crime and crime prevention. States have responded to the notion that crime has become a ‘normal social fact’ (Garland Reference Garland1996) by responsibilising citizens to protect themselves from crime through situational crime prevention measures (e.g. improved car and home security). Another element of this adaptation to high crime societies has been to responsibilise people convicted of an offence in and via the criminal justice system. Rational theories of crime (i.e. that people choose to offend) are emphasised in political rhetoric and policy. As such, systems of punishment which seek to deter offending, incapacitate perpetrators and retributively punish people for their actions have come to dominate purposes of sentencing. Indeed, even where rehabilitation remains an official aim of sentencing, it is increasingly risk-inscribed such that rehabilitative practices have become as much about managing risk as reintegration or building peoples’ strengths and capacities (G. Robinson Reference Robinson2008). Thus, people in prison are asked to take responsibility for their actions and reduce the risks associated with their offending.

As such, blame and responsibility are key concepts in the field of sentencing, and sentencing guidelines stipulate that the seriousness of an offence is linked to the extent to which the perpetrator can be deemed culpable. To some extent, then, a prisoner’s culpability has already been assessed long before they get to a parole hearing. However, the parole oral hearing represents another opportunity in which the responsibility of a prisoner is brought to the fore. This is complex for prisoners to navigate. On the one hand, they need to show they have taken responsibility for their actions whilst, at the same time, needing to show that they have worked to reduce their risk of offending through engagement with rehabilitative programmes and similar interventions. This process risks asking prisoners to be accountable and accept responsibility for past events, creating a ‘double-bind’ for people trying to get released:

maximize your responsibility and appear a dangerous and unscrupulous person, or minimize it and display lack of insight. (Aviram Reference Aviram2020:131)

Moreover, demonstrating one’s responsibility and willingness to be held to account is difficult for prisoners who tend to come from marginalised backgrounds and have low socioeconomic status:

Inmates must be able to talk about how they have been transformed by rehabilitative interventions… these expectations hinge on a personal capacity to (1) verbally express thoughts and feelings, (2) speak in a reflective manner, and (3) produce linguistic utterances in a socially legitimate form. All three capacities are nonuniversally allocated; they are unevenly distributed according to properties such as socioeconomic class, educational attainment, and mental and physical health. (Shammas Reference Shammas2019:151)

One way in which prisoners navigate this double-bind is through demonstrating an insight into their offending behaviour and behaviour in prison, and this feeds into assessments around how manageable a prisoner’s future risk is. We see here how responsibilisation acts as a governance strategy through asking prisoners to have insight:

Insight has a fundamentally individualizing thrust that allows parole power to focus the operations of multiple external agents and agencies … on a single individual while simultaneously construing the inmate’s performance as the work of an atomistic, isolated agent. (Shammas Reference Shammas2019:151)

The responsibilisation turn in criminal justice therefore has particular relevance for parole hearings, as this is a context in which prisoners are expected to demonstrate an understanding of their past responsibility so that future risk can be best managed. The prisoner as a responsible agent is woven into the interaction between panel members and prisoners, particularly through the questions that are asked of prisoners.

Questions and accountability

This study focuses on questioning practices of panel members in parole oral hearings. Tracy & Robles (2009:133) argue that ‘questions are a primary means by which institutions determine truths and amass facts’, and this is true of the oral hearing. Questions and answers dominate this setting, with panel members posing questions to professional witnesses and prisoners. At the most basic level, a question is an utterance that is ‘designed to seek information’ using ‘interrogative syntax’ (Heritage 2002:427). Questions are a ‘powerful tool to control interaction: they pressure recipients for response, impose presuppositions, agendas and preferences, and implement various initiating actions’ (Hayano Reference Hayano, Sidnell and Stivers2013:395–96).

According to Clayman & Heritage (2002:762), no questions are ‘neutral in an absolute sense’ and can vary by how strongly stance and knowledge is presented. Elsewhere, research has investigated the use of why-fronted questions in oral hearings, using a corpus of hearings involving prisoners serving a particular sentence type: Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP). A significant difference was found between remote and in-person hearings in the use of challenging questions, whereby remotely-held hearings contained more challenging why-questions than in-person hearings (Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow, Phillips, Ringrow and Piazza2025). In the current article, hearings involving prisoners serving a range of different sentences are considered, and the analytical focus is narrowed to particular question types: NPQs, WHQs and SQs, all of which foreground the questioner’s negative stance towards the behaviour and/or actions of the prisoner.

NPQs begin with a negated frame such as ‘Don’t you…’, ‘Wouldn’t you…’, ‘Isn’t it…’, and ‘Did you not…’. NPQs typically highlight some problematic behaviour or action of the recipient and seek to elicit agreement from the recipient that their conduct has been, at best, unconventional or, at worst, highly problematic. Studying courtroom interactions, Woodbury (Reference Woodbury1984) found that NPQs often are used to display surprise and scepticism. More generally, NPQs ‘embody the stance that the state of affairs nominated in the question’s proposition is not the case… and… are likewise designed under the aegis of the preference for agreement’ (Heritage & Raymond 2021:42). Such questions ostensibly take the form of a polar question, although ‘these utterances are not always understood as questions’ (Heritage & Clayman 2013:484), such is the degree to which these utterances encode the stance, or assumed stance, of the questioner (Clayman & Heritage 2023:64). NPQs have been described as a highly ‘assertive’ form of polar question (Clayman & Heritage 2002; Heritage 2002; Heritage & Clayman 2013). NPQs are seen to imply a why-question (Yadugiri Reference Yadugiri1986) but can be seen as more assertive as they are based on certain underlying presuppositions. The fact that recipients tend to respond to negative interrogatives with accounts, rather than merely affirming or denying the proposition, confirms this interpretation.

Heritage (2002:1439) argues that NPQs have one or more of the following characteristics:

• The object is a matter of common knowledge between the interviewer (IR) and the interviewee (IE), and most usually, has been the object of the preceding talk;

• NPQs involve propositions that evaluate and question the conduct of the IE and/or their associates in ‘critical, negative or problematic terms’;

• This critical position is embedded with a ‘polarity that invites the interviewee to assent to the criticism, or to endorse the criticism of the conduct of allies’;

• NPQs are ‘argumentative or challenging’, favouring a response that ‘contrasts with their earlier statements or actions, while not permitting them to do so without acknowledging inconsistency’.

As ‘leading’ questions, NPQs strongly prefer positive, affirmative responses from recipients (Heritage 2002:1430; Sidnell Reference Sidnell2004:749) and are a prime example of adversarial questioning. They ‘constrain the content of the response’ (Clayman & Heritage 2023:68, emphasis in original) and are included in Heinemann’s corpus of ‘unanswerable questions’ (2008), in which a confirming response is simultaneously made relevant and undesirable for the recipient.

Further evidence that NPQs are challenging and adversarial is found in their sequential placement. NPQs are often avoided by interviewers, through being abandoned and/or repaired to other forms (Heritage 2002:1432); NPQs are typically used as follow-up questions rather than as a first attempt at getting a response (Heritage & Clayman 2013:492; Raymond & Heritage Reference Raymond and Heritage2021:69); and NPQs often follow a preface that sets the recipient up to be viewed negatively (Piirainen-Marsh & Jauni Reference Piirainen-Marsh and Jauni2012:649; Clayman & Heritage 2023:72).

Interactional research on courtroom discourse has found that NPQs are reserved for highly adversarial sections of the talk. In Aronsson (Reference Aronsson2018), NPQs were mostly found during cross-examination, where an attorney was questioning a witness from the ‘other side’ (i.e. not their client)—a finding that corroborated Woodbury’s earlier work on negative interrogatives in courtroom questioning (1984) and Drew’s research on cross-examination questioning (1990:47). Aronsson also found that NPQs appeared ‘relatively late in the proceedings… where heat has already started to build up’ (2018:42), occurring alongside other devices that are associated with hostility, such as extreme case formulations, ironic rhetorical moves and metacommunication (2018:49).

Given the nature of the corpus we are working with, NPQs are ‘negatively valenced’ (Raymond & Heritage Reference Raymond and Heritage2021), in that these questions focus on prior, undesirable behaviour. In WNQs a canonical why-question is asked in a negative format: e.g. ‘why didn’t you…’, ‘why can’t you…’, and ‘why aren’t you…’. Attention is focused on something positive that did not occur and the recipient’s responsibility for this positive outcome or decision not being pursued. Although there exists a plethora of research on why-questions (e.g. Robinson & Bolden Reference Robinson and Bolden2010; Bolden & Robinson Reference Bolden and Robinson2011; Raymond & Stivers 2016), no studies that we are aware of focus on WNQs. Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen (Reference Thompson, Couper-Kuhlen, Laury and Ono2020) have looked at a similar format, why don’t you X, which they conclude operate to give advice rather than solicit information, proposing a ‘course of action implying an obligation for the recipient’ (Thompson & Couper-Kuhlen Reference Thompson, Couper-Kuhlen, Laury and Ono2020:125–26). Like more canonical forms of why-question, WNQs elicit accounts from recipients, bringing ‘to the surface a claim that the asker cannot make sense of his/her interlocutor’s behavior’ (Raymond & Stivers 2016:324–25). Why-interrogatives are usually disaffiliative and often ‘face-threatening’ (Raymond & Stivers 2016:348), especially in cases where the recipient is deemed responsible for an accountable action (Bolden & Robinson Reference Bolden and Robinson2011:116). Questions highlight the epistemic status of the producer and the recipient (Hayano Reference Hayano, Sidnell and Stivers2013:396), typically positioning the questioner as not knowledgeable and the recipient as knowledgeable. By contrast, why-questions have greater ‘capacity to claim some… rights over, the knowledge being inquired about’ (Bolden & Robinson Reference Bolden and Robinson2011:96). In part, the questioner’s position of knowledge is encoded in stance-taking, with the questioner communicating that the event being inquired into is ‘socially “problematic”’ (Bolden & Robinson Reference Bolden and Robinson2011:95) and something to be criticized or challenged (J. Robinson Reference Robinson and Jeffrey2016:32). Given that WNQs, when focused on the actions and/or behaviour of the recipient, inherently focus on some shortcoming and/or problem with the recipient’s past action or behaviour, it is reasonable to surmise that this format constitutes a more adversarial version of the canonical why-question format.

The third set of questions considered as challenging are statement questions (SQs) in which some negative assessment of the PR’s actions or behaviour is made. SQs involve the speaker issuing a declarative and the recipient hearing, and responding to this, as a question. Despite being non-canonical questions, SQs have been found to be the most prevalent question format in informal American English (Stivers Reference Stivers2010:2773). Questioners may append a tag question, either in positive or negative form, which will confirm the utterance as a question, but SQs also frequently take an unaltered form. As such, hearing an SQ as a question requires recipients to make sense of the utterance in context. In situations where question/answer sequences dominate, it can be inferred that an SQ found in the first position should be heard as a question, especially when issued by someone who occupies the role of questioner. Even though such SQs typically concern a matter that sits within the recipient’s ‘territory of knowledge’, to be heard as questions of confirmation and not statements (Heritage 2012:32) the design of an SQ can suggest that the questioner is also knowledgeable on the subject. Indeed, Sidnell (Reference Sidnell, Alice and Susan2010:26) argues that statement questions typically position the producer as more knowledgeable. SQs without tags are seen as indexing the strongest epistemic stance on the part of the issuer, while SQs with tags are regarded as indicating a relatively weaker position (Cerović Reference Cerović2022:5), albeit a position that is stronger than, say, polar questions (Heritage 2010:48–49). Raymond (Reference Raymond, Alice and Susan2010) found that declarative polar questions not only constrain recipients’ responses more than yes/no interrogatives but also show stronger epistemic commitment on the part of the questioner. Similarly, as SQs necessitate that the speaker adopts a stance on something, giving a viewpoint or presenting a particular situation, such questions can be heard as adversarial. As well as encoding the stance, or assumed stance, of the questioner, SQs also tend to favour an affirmative response (Heritage 2010:43). Cerović (Reference Cerović2022) considered the use of SQs in police interrogations of suspects, finding that the wider interactional context determines how epistemic access operates in these questions. In cooperative sequences, where the aim is to reconstruct events and/or the suspect has already confessed, the interviewing officer produces SQs to confirm information with their epistemic access ‘downgraded’ (2022:12); by contrast, in hostile sequences, where a confession is being sought, interviewing officers use SQs to produce accusations, ‘upgrading’ their epistemic access through a range of features (2022:15–16).

These three forms of question are associated with issuing challenges to and/or accusing the recipient, especially where the recipient’s conduct is the subject of the question. Tracy & Robles (2009:134) argue that questions ‘are account-seekers: they do the job of eliciting, as well as asserting, accounts of reality’. Due to their challenging nature, all three forms of question make relevant the issuing of an account from the recipient, and this is even more the case in oral hearings as the prisoner is expected to provide reasons for actions and predispositions, and the measures they have taken to mitigate the future risk to themselves and to the public. Accounts for behaviour are ‘omnirelevant’ and should be ‘transparently available to interlocutors’ (Raymond & Stivers 2016:348), and in the oral hearing this requirement for prisoners to produce accounts is intensified further, despite this action being generally dispreferred. Indeed, ‘off-record’ forms of account solicitation are preferred (Robinson & Bolden Reference Robinson and Bolden2010:508) and more direct forms of why-questions are ‘withheld until they need to be asked’ (Robinson & Bolden Reference Robinson and Bolden2010:504; see also Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow, Phillips, Ringrow and Piazza2025).

Data and methods

To understand how questions are asked in parole oral hearings, we analysed thirty oral hearings recordings which were obtained from the PB having received approval from our university’s Ethics Committee (ER29879416) and the PB’s Research Governance Group. This corpus comprised fifteen in-person hearings and fifteen hearings conducted by videolink.Footnote 1 Twenty-seven of the hearings were with male prisoners and three were with female prisoners.Footnote 2 The hearings involve prisoners serving a range of different sentences. The hearings analysed took place between February 2019 and May 2021, with seventeen occurring before the onset of Covid-19 lockdown restrictions in the UK (i.e. before mid-March 2020) and thirteen taking place once lockdown measures were in place (i.e. after mid-March 2020). This is relevant because prior to the imposition of lockdown measures most oral hearings were conducted in-person (Padfield 2017), whereas since mid-March 2020 approximately 93% of hearings are held remotely. In this article we do not comment on similarities and differences between hearings conducted pre- and post-pandemic. Beyond what was on the recordings, we were given no information about the panel members who sat on these hearings, and so it was impossible to gauge how experienced a particular panel was with the remote mode. Although remote hearings were relatively rare pre-pandemic, this mode had been used by the Parole Board since 2010 and so it could be reasonably expected that most panel members would have either sat on remote hearings themselves or would have accrued some knowledge of how remote hearings operated. All of the hearings analysed were comprised of three panel members rather than single-member hearings which are reserved for less complex cases and/or risky people. We could tell that two of the panel members sat across two hearings (one sat on a videolink hearing and an in-person hearing, while the other sat on two in-person hearings), but aside from that the panels were comprised of different members. In 2023–2024 the Parole Board had 364 panel members who sit on hearings (Parole Board Reference Parole Board2024:86), up from 269 in 2019–2020 (Parole Board Reference Parole Board2019:70).

The recordings were transcribed by two research assistants and the lead author using standard CA techniques of transcription (Jefferson Reference Jefferson and Gene2004; see the transcription conventions in the appendix). As part of this research project, we conducted interviews with fifteen PB panel members, in which we inquired about perceptions and experiences of different modes of oral hearing (Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow and Phillips2023). To interpret our findings, we draw on these interviews, as well as interviews collected as part of a follow-up study (Ethics Approval number ER56259913). In this second study we conducted interviews with other participants involved in oral hearings: prisoners (n = 21), former prisoners (n = 9), HMPPS staff in probation (n = 7), and legal representatives (n = 5).

The in-person oral hearings involved all members of the hearing co-located in the same room within the prison where the inmate was incarcerated. Hearings conducted by videolink involved the prisoner participating from a room in their prison with conference call facilities, usually with a member of prison staff co-located with them. Other participants in these hearings dialled in from different locations, either their workplace or their homes. We did not have access to video recordings of these hearings because the PB only records the audio from oral hearings. While this lack of visual data is an unfortunate, albeit unavoidable, limitation of the study, it has the benefit of sharpening our analytical focus onto the effect of mode (i.e. in-person vs. videolink) on what is available to us: the audio recording. Panel members, professionals who participate in oral hearings (e.g. legal representatives, probation staff) and prisoners all told us in interviews that the videolink mode introduces problems into oral hearings that are not present in in-person hearings. Thus, it seems reasonable to approach the below analysis in a way that foregrounds the modal difference as a highly relevant—but potentially not the only—factor in explaining differences that are found between hearings conducted by video and those conducted in-person. We reflect on this further in the Discussion section below.

The in-person dataset and the videocall dataset are similar in number of questions asked by panel members to prisoners, although the number of questions in the in-person dataset is slightly higher (see Table 1).

Table 1. The number of questions asked by panel members across the two modes of hearing.

The original aim of the research was to compare the development of rapport between panel members and prisoners across in-person and remote oral hearings. Following transcription, the initial focus was therefore on aspects of the interaction that seemed to promote or hinder the development of rapport between panel members and prisoners. Our work elsewhere has focused partly on practices that helped to promote rapport (Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow, Phillips, Ringrow and Piazza2025), while in the current article we focus on episodes of talk involving robust questioning of prisoners. The use of the three question forms (NPQs, WNQs, and SQs) was striking in this preliminary analysis, and further analysis was performed on these forms. Once these forms had been identified in the data, each occurrence was categorised according to the following inclusion criteria:

• Does the content of the question imply or explicitly state blame or responsibility for behaviour or actions on the part of the prisoner?

• Does the question encode the stance of the questioner and/or some third party (e.g. another professional witness involved in the hearing), where ‘stance’ is understood as displays of ‘feelings, attitudes, value judgements, or assessments’ (Biber, Leech, & Conrad Reference Biber, Leech and Conrad1999:966)?

We included all occurrences of questions that answered ‘yes’ to both criteria. That left a total of forty-three questions out of a total of 2,757 (see Table 2).

Table 2. Frequency of adversarial question types across both modes of hearing.

In the next section we present a more detailed quantitative breakdown of the use of these question types by mode of hearing, followed by analysis of a selection of occurrences found in the videocall dataset. The analytical approach adopted is conversation analysis in its ‘applied’ sense (Antaki Reference Antaki2011) and is therefore rooted in the following ideas: interaction is sequentially organised; turns-at-talk perform social actions such as accusing, blaming, and complaining; and an initiating turn constrains what it is possible to produce in a subsequent turn (Sacks Reference Sacks1995).

Findings

Our focus in this article is on the use of adversarial questioning across remote and in-person oral hearings. Table 3 shows the distribution of the identified three question forms across these two modes.

Table 3. Frequency of adversarial questions in videolink and in-person hearings.

Adversarial questioning was quite rare in oral hearings, accounting for just 1.56% (n = 43) of the total number of questions. This demonstrates that the PB’s aim of avoiding confrontation in the hearings is working effectively overall. As a percentage, the videolink hearings in our dataset contained over twice as many total examples of the adversarial question forms where blame was encoded and the stance of the questioner/third party was present. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between mode of hearing and the use of adversarial questions. The relation between these variables was found to be significant (χ2 (1, N = 43) = 6.2, p = .012) meaning that panel members were more likely to use adversarial questions in remote hearings than in in-person hearings.

Negatively polarized questions (NPQs)

There were four instances of NPQs in the videocall dataset and a solitary example in the in-person dataset.

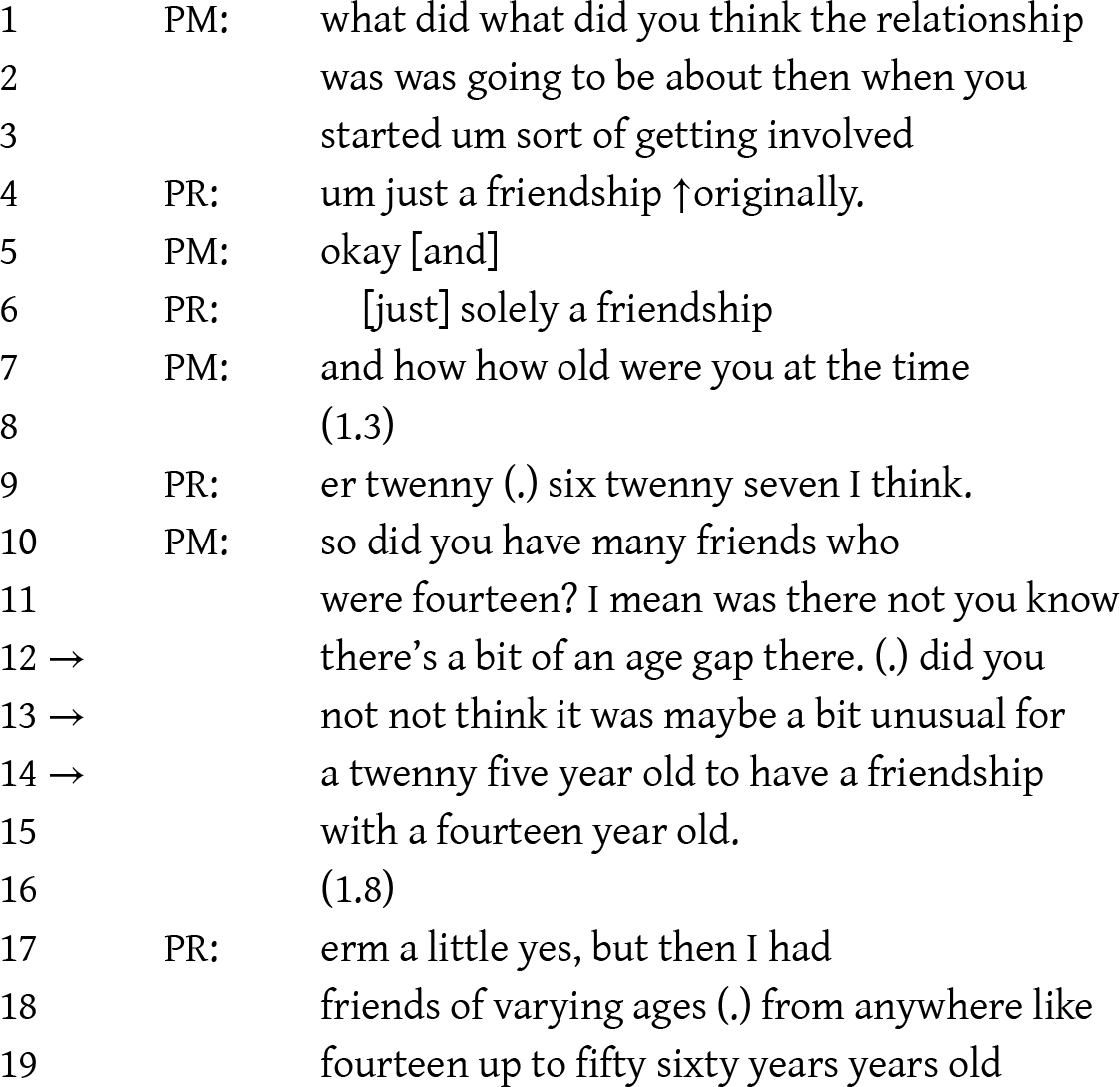

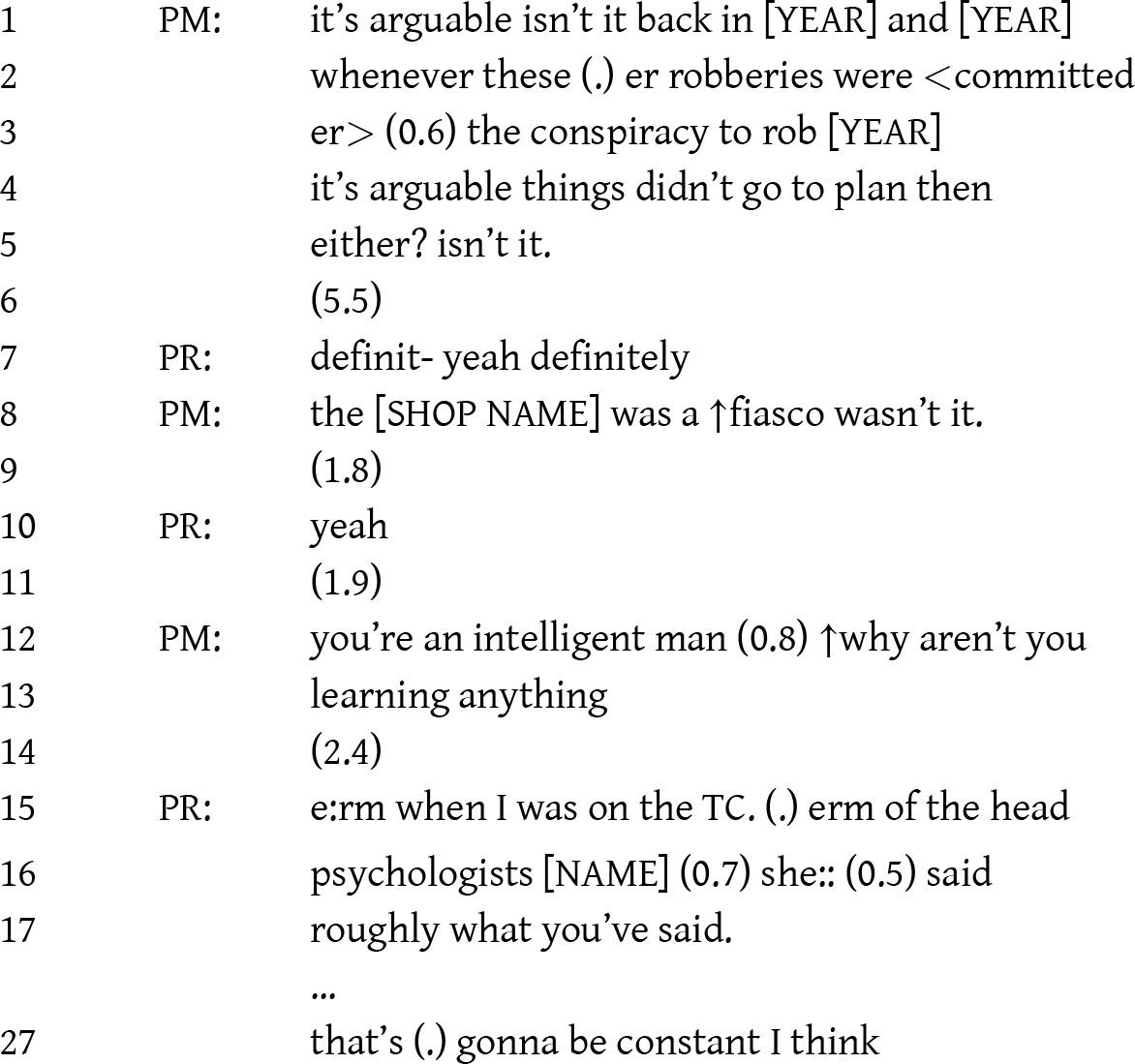

In the first example a prisoner is being questioned in a videolink hearing about his ‘index’ offence, the offence that brought him to prison in the first place.

(1) VideolinkPre5; PM: Panel member, PR: Prisoner

Before the NPQ (“did you not think it was maybe a bit unusual…”), the panel member asks a ‘what’ question to elicit a view from the prisoner on the nature of the relationship with the victim: “what did you think…”. The prisoner responds by emphasising the normality of the relationship: it was “just a friendship”. Once the age of the prisoner at the time of the offence is confirmed, the panel member moves on to issue questions in a more robust fashion, asking multiple questions in one turn (lines 10–15):

• “did you have many friends who were fourteen?”

• “was there not you know there’s a bit of an age gap there?”

• “did you not think it was maybe a bit unusual…?”

The latter two take NPQ form,Footnote 3 suggesting that NPQs are used as a subsequent strategy once another form has been attempted. Through the prisoner’s response we can tell that they hear the question as a challenge: he provides qualified agreement with the position taken by the panel member (“erm a little yes”, line 17), before moving on to offer an account that normalises the relationship: “I had friends of varying ages” (lines 17–18).

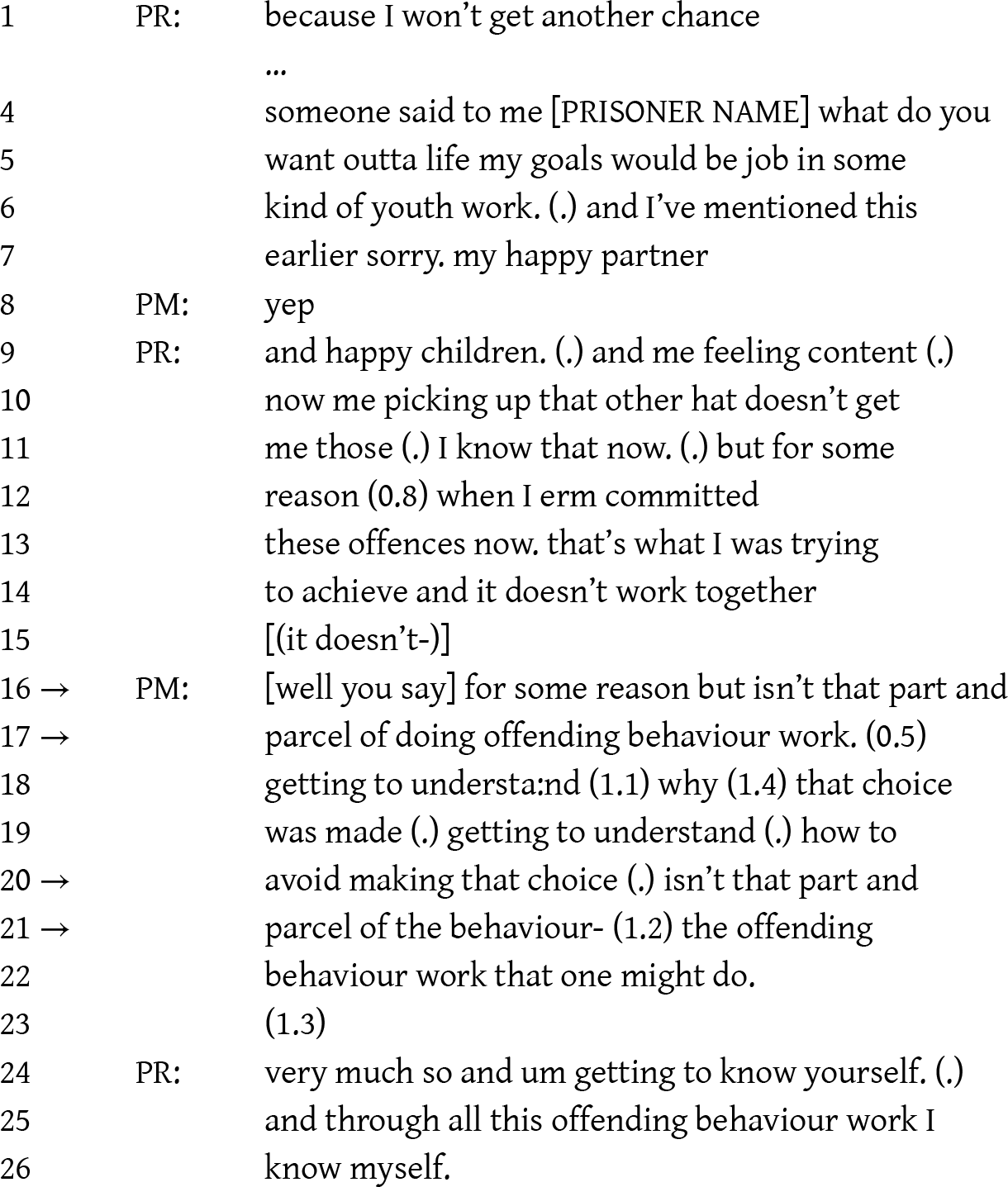

The second example of NPQ use is taken from a different videocall hearing. It appears in a section of talk focused on a prisoner’s understanding of why he has persistently committed offences.

(2) VideolinkPre4

The prisoner compares his previous offending behaviour with his current outlook. He claims to recognise now that his previous offending behaviour was not commensurate with his desire to fulfil his “goals” in life (line 5). The panel member takes issue with the prisoner’s claim, picking up on the vague wording in the prisoner’s turn (“for some reason”, line 16) and challenging the quality of the learning and insights that the prisoner has developed. This challenge takes the form of an NPQ: “isn’t that part and parcel of the… offender behaviour work that one might do?” (lines 20–22). As in extract (1), more than one question is asked in the panel members’ turn, although on this occasion the NPQ form is repeated rather than different question forms being asked. The overall effect, however, is a similarly robust and adversarial questioning. The prisoner’s response confirms that the panel member’s question is heard as a challenge: he responds with agreement (“very much so”, line 24) and with additional information that upgrades the assessment (Pomerantz Reference Pomerantz, Atkinson and Heritage1984) to show his independent perspective (“and um getting to know yourself”, line 24).

In both cases presented, NPQs are used by panel members as a way of issuing a challenge to some facet of the prisoners’ behaviour or disposition, and to challenge something that the prisoner has said (extract (2)) or something not said (extract (1)). These NPQs are heard as challenges that the prisoners agree/disagree with (both prisoners here agree to some extent with the challenge) and make relevant the production of accounts. In both cases, the NPQs strongly prefer an agreeing response that is based on commonsense assumptions about appropriate behaviour: that an adult engaging in friendships with children is problematic (extract (1)), and that committing further offences demonstrates that offending behaviour has not been properly addressed (extract (2)).

Why + negative questions (WNQs)

Like NPQs, WNQs in the hearings function to highlight some prisoner behaviour, disposition, or action that is problematic. WNQs achieve this by explicitly pointing to some preferred, alternative behaviour that was not undertaken. As with NPQs, these questions are heard as challenges by the recipients, prompting either acceptance or denial, along with an account. In the videocall dataset we identified ten examples of WNQs (0.8% of the total questions), compared with seven examples in the in-person dataset (0.5% of the total questions). Below we present three examples of this question in operation in the videocall dataset.

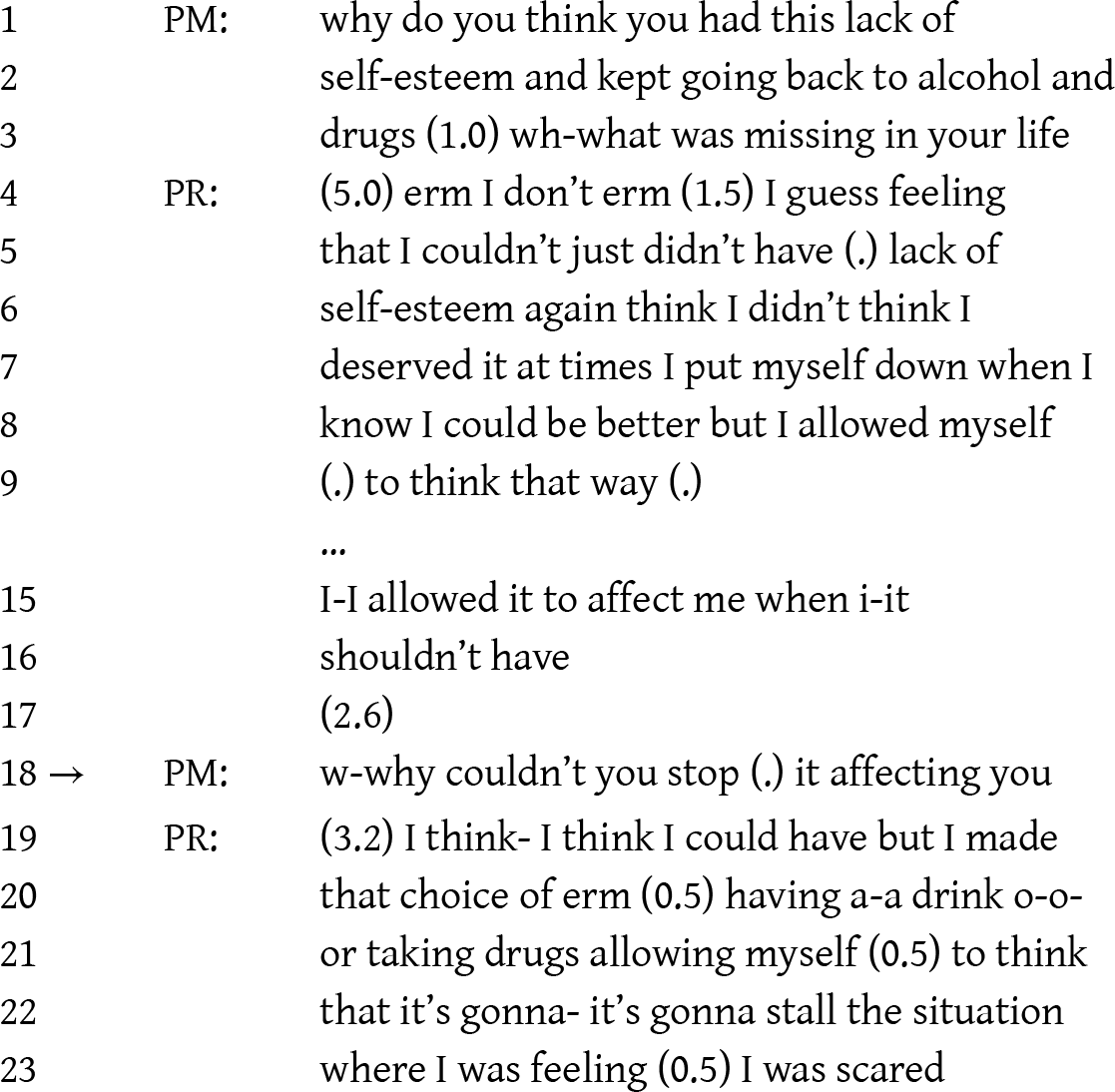

In the following extract the panel member is questioning the prisoner about their past dependency on drugs and alcohol. At the arrowed turn, the panel member uses a WNQ to interrogate why the prisoner was unable to “stop” their life situation “affecting” them negatively.

(3) VideolinkPost1

While the arrowed turn at line 18 is prompted by the prisoner’s previous account and explanation that they “shouldn’t have” allowed situational factors to affect them (lines 15–16), the WNQ goes further, taking the position that the prisoner “could” have taken the alternative, preferred option (i.e. to not let the situation affect them). In response the prisoner, following a lengthy pause, begins by orienting to what they “could have” done, and then takes responsibility for not managing this preferred course of action (lines 19–20). The answer provided therefore picks up on, and confirms, the embedded stance and blame conveyed in the question.

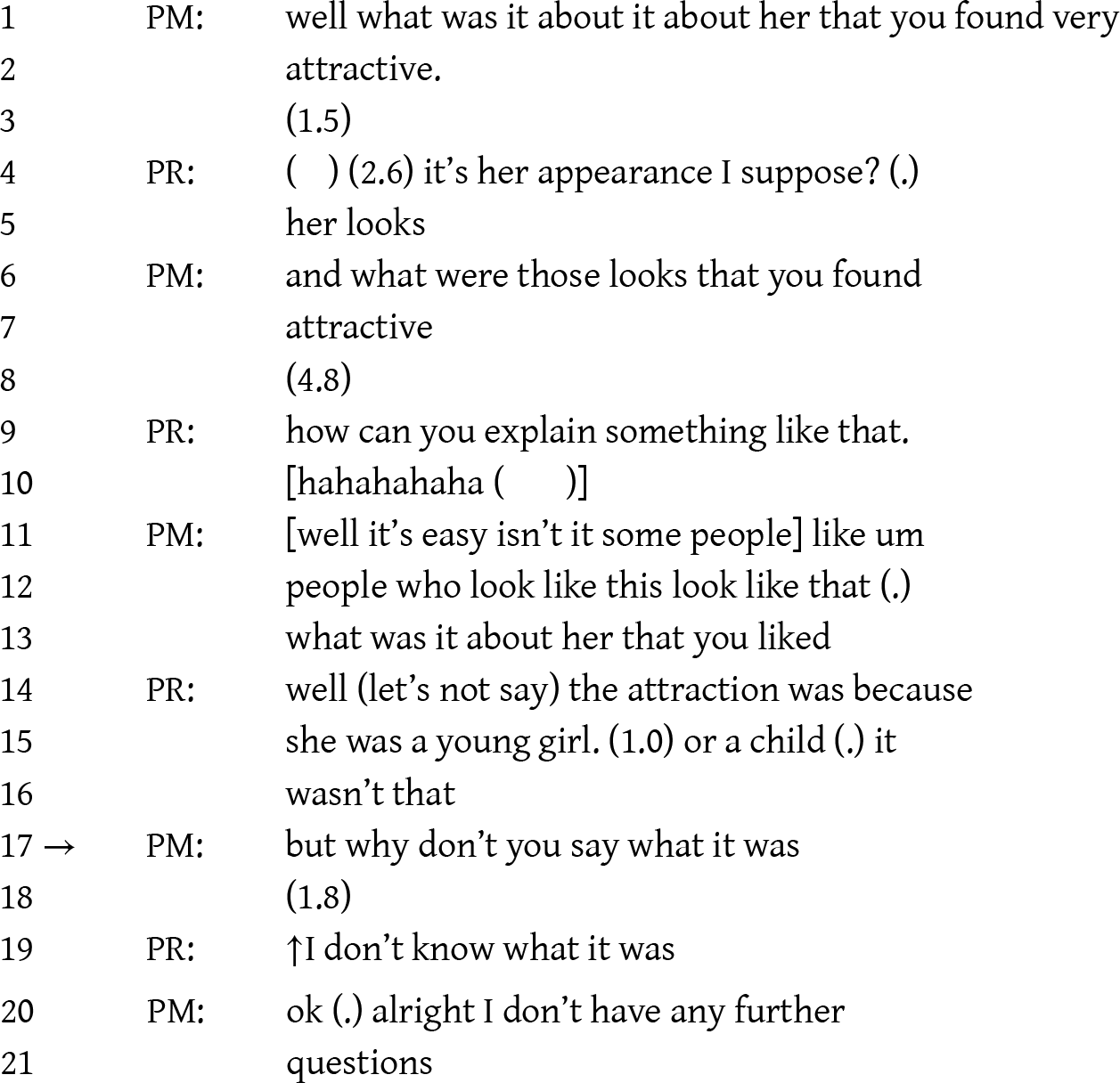

In the next example, a prisoner is questioned about their attitude towards a sexual offence that brought them to prison. Prior to the extract, the panel member had been attempting to ascertain the prisoner’s feelings, at the time of the offence, towards the victim.

(4) VideolinkPre6

In this extract, the panel member tries repeatedly to get the prisoner to divulge the ways in which he found the victim “attractive” (lines 1–2). The prisoner resists providing a definitive answer to this, although the cause of this resistance is unclear: the prisoner’s view is that such things are unexplainable (line 9), while the panel members’ view (as inferred by the prisoner) is that the prisoner is concealing information and, by implication, not recognising the severity of the offence (lines 14–16). The WNQ is used by the panel member after different versions of ‘what’ questions have failed to elicit a satisfactory response. The repeated use of the ‘what’ question, and the prisoner’s view that they have answered the question as well as they are able, leads the prisoner to infer that the question is trying to elicit an answer that would confirm that the prisoner had an abnormal and predatory sexual inclination towards young girls or children. In response to the prisoner’s emphatic denial, the panel member counters with a WNQ: “why don’t you say what it was?” (line 17). This produces an injunction for the prisoner to either say in what ways they are attracted to children or to provide some reason as to why they are unable to shed light on their sexual inclination. The prisoner responds with neither of these, instead re-emphasising his lack of insight on the matter: “I don’t know what it was” (line 19).

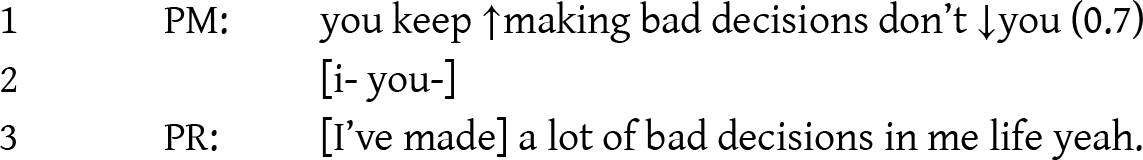

In the next example of a WNQ from the remote hearing dataset the panel member is questioning the prisoner’s extensive offending history.

(5) VideolinkPre4

The panel member is questioning the prisoner about his history of committing robberies, with the view of ascertaining why these offences were committed. Before issuing the WNQ the panel member asks two questions in declarative form with negative tag: “it’s arguable that things didn’t go according to plan then either isn’t it?” (lines 1–4) and “the [SHOP NAME] was a fiasco wasn’t it?” (line 8). Both questions are replied to with minimal affirmatives (lines 7 and 10). To garner a more substantive reply, the panel member then intensifies the questioning, issuing a WNQ: “you’re an intelligent man, why aren’t you learning anything?” (lines 12–13). The question presents the responsibility as resting with the prisoner: he should be learning from previous errors (the preferred outcome for offenders), and this learning should be easier because of some personal quality about the prisoner: he is “intelligent”. The stance of the panel member is encoded in the question, namely that this prisoner’s ‘intelligence’ places him in a privileged position to rehabilitate, yet he is wilfully choosing not to learn from previous offending mistakes. In reply, the prisoner offers an account that provides corroboration of this description of him, before conceding that this disposition towards offending behaviour may be a “constant” problem (line 27).

As with the NPQs, the panel members’ use of WNQs serve as a way of making relevant accounts from prisoners, and specifically accounts that involve the prisoner admitting blame or responsibility for actions, behaviour, and/or dispositions. The WNQs present the prisoners as choosing some damaging course of action in favour of another, socially preferred course of action: in extract (3) the prisoner could have chosen not to let their life situation affect their drink and drugs problem, in extract (4) the prisoner should be able to show greater insight into their offending behaviour, and in extract (5) the prisoner ought (especially by virtue of being “intelligent”) to be able to desist from committing repeat offences. In as much as these WNQs are built up to by the panel members (i.e. panel members do not start by asking about the topic using this question type), WNQs serve as a final strategy for eliciting accounts from the prisoners that accept blame or responsibility when other questioning strategies have been exhausted. In extracts (3) and (5) the prisoners respond in this preferred way, while in extract (4) the prisoner falls back on a claim that they cannot answer the question.

Statement questions (SQs)

The final question type considered are SQs. As discussed above, this design of question has the potential to be adversarial and, as with the NPQs and WNQs, the examples of SQs analysed from the dataset were those that involved the questioning panel member presenting a negative stance towards the prisoner and implying (or making explicit) blame or responsibility on the part of the prisoner. Although there were only a relatively small number of SQs that encoded stance and blame in the dataset, there were over twice as many of these found in the videolink hearings as a percentage of the total questions (see Table 3). Below we present three examples from the videolink hearings.

In the following extract the panel member and prisoner are discussing the prisoner’s past decision-making. The panel member issues a statement question with negative tag.

(6) VideolinkPre3

The question overtly highlights the panel member’s stance on the prisoner’s prior decisions: these “bad decisions” are presented as habitual for the prisoner (“keep making”). The question also presents the responsibility for the bad decisions as laying with the prisoner. The prisoner acquiesces, upgrading the bad decisions to “a lot of bad decisions”, and appearing to agree that the responsibility for these belongs to them.

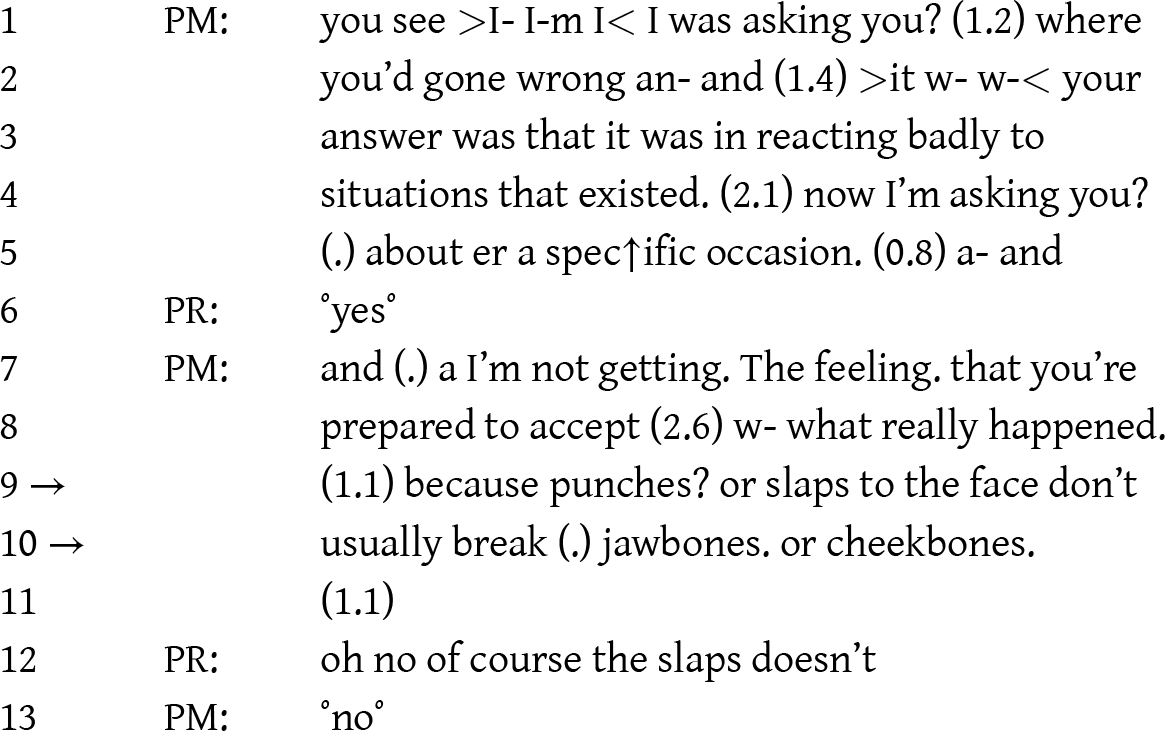

The next extract is more complex in the build-up but, as with the previous example, a statement question is asked—this time without a tag question.

(7) VideolinkPre1

The questions here focus on an offence in which the prisoner attacked their partner. As with extract (6), the panel member makes it clear that the prisoner is blameworthy for this event. The difference between the extracts is that, for the panel member in extract (7), the prisoner is seeking to diminish their responsibility for the attack. Having summarised the prisoner’s previous answers, the panel member moves onto make explicit their reasons for continuing with the line of questioning: “I’m not getting the feeling that you’re prepared to accept, what really happened” (lines 7–8). The panel member’s stance on the prisoner’s previous answers is therefore made clear, as is their stance on the veracity of the information on file about the offence: the prisoner’s answers are presented as overly diminishing of their responsibility and do not match up with the evidence on file. The question in this extract that receives a more significant reply takes a statement form: “punches or slaps to the face don’t usually break jawbones or cheekbones” (lines 9–10). The prisoner agrees with an upgrade—this time in the form of an ‘oh’-prefaced answer (Heritage 1998): “oh no of course the slaps doesn’t” (line 12). The prisoner does not attend to the “punches” element of the question as it is their contention that they did not punch (only slapped) their partner in this altercation.

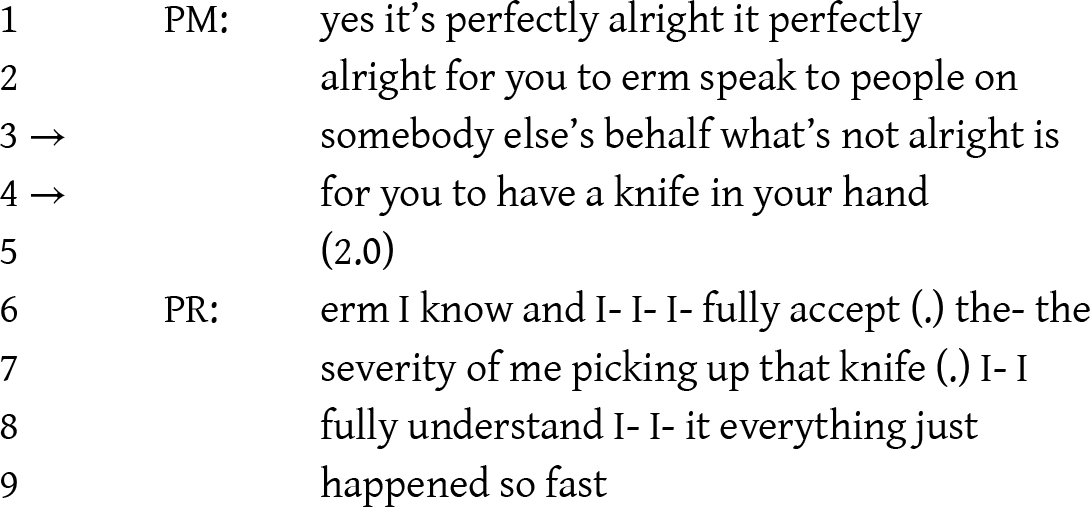

Extract (8) comes from a longer discussion about an offence that led to a prisoner being recalled to prison. Again, the stance of the panel member is evident in their turn at talk, and this stance involves a negative judgement of the prisoner’s behaviour leading to their recall.

(8) VideolinkPre9

The panel member describes a course of action that would have been acceptable (the prisoner speaking “to people”, lines 1–2) as compared with the unacceptable action that the prisoner did engage in (having “a knife” in their hand, lines 3–4). This is delivered as a statement observation. Whereas in the previous two examples the panel member’s statement seems to be heard straightforwardly as a question to answer, in extract (6) the negative tag ensures that it is heard as a question, and in extract (7) the panel member explicitly describes what they are doing as “asking”; in extract (8) the panel member’s statement is responded to as an account solicitation, such as is the expectation in this interactional context that utterances made by panel members to the prisoner should invite some answering response.

Discussion

As far as the Parole Board is concerned, remote hearings are ‘safe and effective’ (Parole Board Reference Parole Board2022:11). This assumption underlies the decision to persist with remote hearings as default since the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions. Hearings conducted by videolink and those conducted in-person are generally organised in the same way, with evidence taken in turn from witnesses and prisoners. However, we have found that, within our sample, the interactional exchanges in oral hearings conducted by videolink do differ from those conducted in-person (see also Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow and Phillips2024). Here, we have analysed three question types used in oral parole hearings that are on the adversarial end of the scale of questioning: NPQs, WNQs, and SQs. These question types can be highly challenging, and to further prove that these are adversarial we have focused on collected examples in which the panel member includes a stance and implicitly or explicitly holds the prisoner as responsible for the negatively assessed behaviour, disposition, or action. We have concentrated on the use of these question types in oral hearings that are held remotely by videolink. In-person hearings also contain such questions, and thus sequences of talk that seem to be adversarial. However, in remote hearings these question types are used to a greater, statistically significant, degree.

In our interviews with PB panel members, professionals who give evidence in oral hearings, and prisoners, participants from all groups agree that remote hearings are more likely to feel ‘impersonal’ and ‘informal’ (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Peplow, Oliver and Purnell2025). For some, this is liberating, making them feel less anxious about participating, while for others the ‘barrier’ of the screen feels both distancing and gives off the sense that the seriousness of the context is not being respected. This potential for remote hearings to feel more informal and impersonal underpins our below interpretations for why adversarial questioning might be more prevalent in remote hearings.

The impersonal nature of remote hearings is associated with the material conditions of that mode. Various interviewees were concerned about the effects of the prisoner being physically isolated during remote hearings, especially in cases where their solicitor was not co-located with them. Some of the prisonersFootnote 4 we spoke to told us that they felt detached in remote hearings, like they were participating via a television (William, Prisoner; Robert, Prisoner; Jenny, Prisoner) and that the whole experience was not “real” (Richard, Prisoner). The motif of the screen as a ‘barrier’ in remote hearings, and the technological problems associated with these hearings, and VMC more generally (see Literature review above; Peplow & Phillips Reference Peplow and Phillips2024), may result in panel members (consciously or unconsciously) over-compensating and adopting a questioning style that is more challenging and direct. Indeed, some of the prisoners we interviewed reported the remote hearings can feel more procedural than in-person hearings, with panel members “chucking questions” at prisoners (Jonny) and “not really listening” to the answers (William, Prisoner). Some panel members reported feeling more empowered to be direct with the removal of physical co-presence in the remote mode. One reflected on whether panel members are “less inhibited and a bit harsher in our questions” in remote hearings (PB3Footnote 5), while another panel member reported a general feeling amongst panel members that they felt “more confident in asking much harder” questions because of the lack of physical co-presence with the prisoner (PB4).

If the above perspectives endorse an interpretation that the remote mode is experienced as more impersonal, then also at play are feelings that these hearings feel less formal. Professional witnesses and panel members told us that it is harder to be focused during a remote hearing because of the possibility of technological breakdown and “distractions”, such as mobile phones—the temptation to check your phone and other peoples’ phones going off (Lucy, Legal Representative; PB7)—and checking emails (Fred, Probation Officer). One panel member told us that as the remote mode feels more “casual”, and the “screen takes that reality” away, this can detract from the “gravitas of the situation”, creating a different relationship between panel members and prisoners (PB8). Several panel members reported feeling compelled to modify their behaviour to counteract the informality of remote hearings: which can “undermine the confidence in the process” (PB10).

It seems plausible that one way of ensuring heightened formality in the remote mode would be to engage in more direct and adversarial questioning. Indeed, several panel members stated that exercising “control” over a remote hearing is more difficult than in in-person hearings. This relative lack of control in remote hearings meant it was more difficult to ensure that the hearing was “investigative rather than… adversarial”:

you also need that control, the ability to exercise control within the interview and establish the right kind of relationship with the interviewee but we tend to be more… investigative… so, again, you need to make sure that setting is set up—that is easier to do face-to-face because you can give that reassurance to the prisoner. (PB14)

Conclusion

This research has contributed significantly to our understanding of how oral parole hearings work, and specifically how the mode of the hearing affects the way that questions are put to prisoners. The oral hearing provides panel members with the opportunity to assess the risk posed by prisoners. By contrast, for the prisoner, the oral hearing is a relatively unique opportunity to present themselves as someone who has learnt from previous experience and undergone the necessary rehabilitation to be released. The oral hearing therefore is a high-stakes interactional event, with panel members making judgements over the release of people, and prisoners trying to ensure that they present themselves as authentically reformed individuals.

The way that oral hearings are conducted has changed significantly in the last few years, and particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic. Remotely-held oral hearings, once used in a minority of cases, are now the default mode. That said, it is important to acknowledge that things may have changed from the time of data collection. It is likely that hearing participants will now be more accustomed to working remotely than when the hearings under analysis in this article were conducted. On the face of it, remote hearings are conducted in a similar way to in-person hearings, and there seems to be an assumption that the remote mode can replicate in-person hearings, with the same format straightforwardly transferring from one mode to the other. While this assumption is borne out in the main, we have identified in this article some differences in the questioning undertaken by panel members across the modes. Panel members are more inclined in remote hearings to ask questions of prisoners that are adversarial, although the number of adversarial questions were low. We assessed this by focusing in on questions that fall into one of three types—NPQs, WNQs, and SQs—and where panel members present their own viewpoint (or, occasionally, someone else’s viewpoint) on the prisoner’s conduct and highlight the prisoner’s responsibility for engagement in this conduct. Previous research had established that two of these question types are often adversarial (NPQs and SQs), but this is the first study, of which we are aware, that has focused on WNQs.

In the most extreme cases, these behaviours result in the prisoner being presented, through the questioning, in a highly negative light and chastised for previous conduct. This can be understood as a manifestation of the responsibilisation agenda seen across criminal justice policy over recent years whereby prisoners are frequently asked to take responsibility for both their actions and their rehabilitative efforts.

We are not arguing that prisoners should not be asked challenging questions in oral hearings. Indeed, such challenging questions may be necessary where prisoners seem evasive in their answers and/or engaging in verbal behaviour that seems to tactically diminish their responsibility. However, that such questioning appears more frequently in remote hearings is important. If the Parole Board for England and Wales is to deliver on its aim that oral hearings are inquisitive and not ‘adversarial’ (Parole Board Reference Parole Board2023:6) then further training work needs to be delivered to guard against remote hearings developing into an unnecessarily more challenging and adversarial context.

Appendix: Transcription Conventions