Introduction

In the photos of British fascist group Patriotic Alternative's first national conference, Laura Towler stands beaming in her vintage polka dot dress and red-lips, next to neo-Nazi Mark Collett, former member and youth leader of the British National Party.Footnote 1 In her speech, she dresses up his violent politics in the language of (white) endangerment (Duchêne & Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2007) and herself as restoring the Britain of her grandma. ‘We will not be replaced’, she declares, and ‘White Lives Matter’, positioning white British community as threatened by elites and racial minorities’ claims to justice. In Patriotic Alternative's digital livestreams, this discourse becomes a folk song. Jody Kay strums ‘Here's to England’ over aestheticized images of Englishness, castles, and country pubs, while her sweet voice strains ‘our heart and soul, our blood and soil’ which echoes German fascism.

Laura and Jody are the Yorkshire and Southwest regional leaders of UK based Patriotic Alternative, Ltd, (PA), a British fascist political organization and registered business. PA is home to many former members of proscribed violent UK neo-Nazi street gangs such as National Action (NA) and the British National Party (BNP). The organization is characterized by Hope Not Hate, a UK anti-hate charity, as ‘UK's most active fascist organization’. PA can be considered fascist due to their extreme nationalist messaging of white racial and national renewal through the removal of all Jews, immigrants, and people of color, its threat to democracy and personal freedom, its anti-marxism and celebration of economic protectionism, and its aspiration to be a mass movement—all characteristics that Richardson (Reference Richardson2017), drawing on Billig (Reference Billig1978), considers to be constitutive of fascism.

In her YouTube interviews and on the PA website, Towler describes the organization she leads as ‘defending the rights of our people’, ‘supporting our community’, and doing ‘grandma nationalism’. However, this defense also takes the form of organized attacks on asylum accommodations near Liverpool, Luton and in the Birmingham area as well as in Erskin in Scotland. While Laura's husband Sam is currently in prison for hate crimes, Kristofer Kearney, another leading member of PA, was also sentenced in 2023 to four years and eight months in prison for having encouraged violence in the battle against white genocide and disseminated dozens of documents encouraging extreme right-wing terror attacks. This included the manifestos associated with the Christchurch white supremacist attacks which spoke of the ‘great replacement’ theory. Differently from their male counterparts, Laura and Jody rebrand PA's violent fascist politics with a sweet voice in order to make them desirable, mundane, appealing not only to violent men, but to women, white families, and sections of British society for whom hyper aggressive fascist, street-gang violence may be alienating. Grandma nationalism is part of a long history of duplicity in British fascist discourse, using Britishness to distance itself from fascism while embracing the same values (Richardson Reference Richardson2017). This article analyzes PA's branding effort as fascist metapolitics, the cultural struggle for political power. Such efforts do not merely normalize fascist ideologies but also bring together warm affect and racist ideology to build a public desiring this message—recruiting mundane practices to do fascist metapolitics.

This article focuses on PA's branding, the circulation and regimentation of their messaging, and the desiring publics they build. PA's branding centers on the great replacement conspiracy theory. Linked to US neo-Nazi David Lane's conspiracy of white genocide (ISD 2023), the great replacement is a conspiracy theory developed by Austrian neo-Nazi Gerd Honsik in 2005 and far-right identitarian Renau Camus later in 2010. Co-opting discourses of endangerment (Duchêne & Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2007), the great replacement claims that elites, often imagined as Jewish,Footnote 2 aim to replace white indigenous Europeans with Black and Muslim immigrants. This is seen as destroying Europeans’ natural love for their identity and uprooting links between their land, race, and culture (their blood and soil), replacing strong Whites with deracinated, docile, feminized outsiders. Cultural critique and social change, such as celebrating ‘indigenous people's day’, is also reframed as white endangerment. Celebrating diversity becomes white deracination, an elite plot to reduce the love white people have for themselves, their traditions, and patriarchy. A loss of love of country also means a decline in white birthrates and the endangerment of the white race (Burnett & Richardson Reference Burnett and Richardson2021; Tebaldi Reference Tebaldi2021). This messaging, which is at the core of PA's political ideology, is also taken up by several far-right parties in Europe. Some of them hold government responsibility such as Meloni's Fratelli d'Italia, Orban's Fidesz, and Morawiecki's Law and Justice. Others aspire to do so, such as Le Pen's National Rally, Abascal's Vox or Chrupalla's and Weidel's Alternative for Germany. All use discourses of endangerment to couch fascism as a defense of indigenous white Europeans, often imagined as tribal communities. PA presents itself as aiming to build just such a community.

PA turns the great replacement into a brand, narrating threatened whiteness, selling this story, and using it to build white community. On their website, just below a sign reading ‘White Lives Matter’, a large clock counts down the years, days, even the seconds until white people are a minority in the UK much like the climate clockFootnote 3 counts down the years until the oceans boil. Twisting around discourses of diversity to preserve whiteness, identitarian politics become voices of endangerment (Milani Reference Milani2007) which use the language of linguistic, cultural, and biological diversity (Duchêne & Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2007) as they reframe white supremacy as a defense against this great replacement of white Britons by black and brown immigrants. As of this writing, there are 59 seconds, 50 minutes, 16 hours, 127 days, and 43 years until the UK is no longer majority white. PA's narrative of endangered whiteness creates an effective brand for the organization, which is translated into different economic activities including small white businesses selling products branded as ‘fighting the great replacement’ and ‘fighting woke capitalism’, digital content creation, and the creation of a digitally operating network with other entrepreneurs who are already branding their services and products as white. Finally, this brand of ‘fighting the great replacement’ builds community. It discursively reconstructs fascist politics, including the removal of all non-white people from Britain, as defense of white indigeneity. It can therefore become properly British, a stance and practice to be loved, desired, and further propagated. This offers a discursive space in which this love for the English country, for the white race, for the white family can be sometimes practiced and intensified, sometimes rediscovered and expanded to English, white publics who had been made blind, or simply resigned, to the replacement of the white race or had been alienated by the more violent, muscular forms taken by former attempts to reclaim white Britishness. Extending what Maly (Reference Maly2023) calls metapolitics 2.0, or the digitalization of the cultural battle for political power, to explore branding as a site for political activism, we see PA's branding activities then as metapolitics, a discursive, cultural, and economic project which fights for a white nation.

In this article, we explore Laura and Jody's circulation of a fascist narrative of racial replacement designed to build a white public in three steps: (i) branding as circulating ideologies as commodities by looking at their brands Grandma Towler's Tea and Clean and Pure Soap; (ii) branding as creating—and selling—community, looking at their livestream and Tea Time with Sam and Laura; and (iii) branding as regimenting meaning, looking at their Telegram channels. PA sells fascist branded products designed to produce a discursive space where fascist ideas can be shared and cultivated—from tea, imagined to be producing a space of white conviviality, to Tea Time with Sam and Laura, which reproduces this space online and circulates its fascist vision to a larger public, who are invited to participate in a community aligned with this ideology.

This analysis of the mundane semiotic practices used by fascists to win cultural hegemony and a desiring public extends existing work in critical discourse studies on the discursive normalization of the far-right. In particular, we build on work on the communicability of evil (Milani Reference Milani2020), that is, the semiotic processes by which fascist ideologies become mundane and spread across sites of everyday life. We bring this literature together with work in language, nationalism, and political economy (Duchêne & Heller Reference Duchêne and Heller2012), how the language of branding articulates economic logics with nationalist ideologies, and, in particular, work on branding (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2012) and nation branding (Del Percio Reference Del Percio2016) as sites for fascist metapolitics. This makes a contribution to research on the normalization of far-right discourse, going beyond distancing from terror (Urla Reference Urla2012) and mainstreaming in media or political discourse (Wodak Reference Wodak2020; Krzyzanowski & Krzyżanowska Reference Krzyzanowski and Krzyżanowska2022) to look at branding as sites for gaining cultural and political power. PA, we argue, uses the affordances of platform capitalism to build and monetize community, to make their ideology into a commercializable product and to build a public who desires it. PA's branding is an ideological project which is at once discursive—rebranding racism as threatened white indigeneity, commercial—its revenues funding PA's political activities and a white economy, and affective—building the desire for a white nation. It is branding as metapolitics.

Branding as metapolitics

Branding (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2012) and nation branding (Del Percio Reference Del Percio2016) have characterized a large literature on the ongoing reconstitution of the nation and nationalism on the terrain of marketing and the economy (Aronczyk Reference Aronczyk2013). Here we build on contemporary branding scholarship in linguistic anthropology (Manning Reference Manning2010), specifically work exploring the semiotic processes by which associative links are produced between a given product, a name/logo, and specific, often morally valued meanings. Del Percio (Reference Del Percio2016), for example, argues that as a powerful semiotic technique, branding allows marketers to create desire and distinction by imbuing a thing—be it a product, a service, or a person, a people, a nation—with specific meanings and qualities, which, as Gal (Reference Gal2013) notes, are often moral, sensuous, but also affective, and to turn these things into tokens or icons of these meanings and qualities. In this article, we show that branding, however, does not only act upon the branded thing, saturating it with meaning and value, but also on its publics, that is, its consumers who are asked to desire it, buy and possess it, and adjust their behavior and moral values around the meanings, qualities, and values that the thing they buy and consume is made to stand for. So, branding adds and circulates meaning, constructs desiring publics, as well as shapes and frames engagement and practices of consumption (Graan Reference Graan2022).

We extend this literature by theorizing the branding of PA as metapolitics 2.0 (Maly Reference Maly2023), that is, the extension of the Nouvelle Droite's push for cultural hegemony beyond intellectual culture to numerous aspects of daily life as facilitated by the digital sphere—here branding techniques and platform capitalism. Metapolitics 2.0 shows that contemporary far-right politics complements political violence offline with forms of digital innovation allowing the widening of targeted publics and the shaping of new forms of political organizing imagined to be softer, but potentially more effective. The affordances of platform capitalism allow fascist branding to recruit people's everyday lives, their desires, subjectivity, behavior, and social relations to create the cultural change needed for fascist political power.

We direct our focus to those branders and content creators who, like Laura and Jody, use branding to do metapolitics, and who we understand as both metapolitical influencers (Maly Reference Maly2020) and ideological entrepreneurs. The term ideological entrepreneurs originates in economics (North Reference North1981; Storr Reference Storr and Chamlee-Wright2011) where it referred metaphorically to a thinker who ‘captured the ideological marketplace’ (Storr Reference Storr and Chamlee-Wright2011 cited in Van den Bulck & Hyzen Reference Van den Bulck and Hyzen2019:48), that is, someone who ‘innovated’ new models of thinking about the world and competed against other models, entrepreneurs, or common sense. The term was adapted by Hyzen & Van den Bulck to characterize those influencers such as Alex Jones who use affordances of social media and platform capitalism, such as idealized self-presentation (Devos, Eggermont, & Vandenbosch Reference Devos, Eggermont and Vandenbosch2022), beauty, and branding (Gnegy Reference Gnegy2017) to spread an ideology, much as influencers might do it to gain fame, followers, or money, and then further developed by political theorist Alan Finlayson (Reference Finlayson2021) to explain how and why populist politics is more successful in platform capitalism.

In this article, we use ideological entrepreneurs not as a metaphor for the intellectual marketplace, but quite literally as people selling and monetizing ideology to create political engagement and what PA calls community. Taking ideological entrepreneurs literally means, for us, exploring how economic infrastructures keep serving the shaping of nationalist formations and the perpetuation of national communities. Like print capitalism, which created the condition for modern nationalism (Anderson Reference Anderson1983) and helped restructure imperial political formations into national ones (Heller & McElhinny Reference Heller and McElhinny2017), platform capitalism is strategically mobilized by far-right organizations such as PA to interconnect current and future members of its community, forming a public which participates in—and monetizes—its fascist ideology. It is not simple to assess with precision how much revenue PA generates on these digital platforms. Many of their accounts remain hidden in a way that prevents us from getting a detailed understanding of how much money PA generates on them. We know, however, from Squire & Wilson's (Reference Squire and Wilson2022) analysis of revenues generated on Subscribe Star—an online subscription platform used by far-right propagandists, conspiracy theorists, and purveyors of medical misinformation—that in 2022 PA's leader Laura Towler made $1,452 per month on this platform. Subscribe Star is however only one of the several digital platforms that Laura and other PA members use to generate funds (and not the most commonly used by PA). Others are Odysee, Entropy, and Youtube.

Multisite digital platforms, we argue, interconnect people, organizations, and resources in an interactive ecosystem contributing, like print, to a fantasy of immediacy, intimacy, collectivity, and co-participation (Anderson Reference Anderson1983). They create a discursive space for a shared, racist register, one, which like national languages, does not only help to spread national, or, better here, fascist ideologies, but are world making, that is, shape subjectivities, social relations, and an entire moral order constituting this reborn white world (Tebaldi Reference Tebaldi2023). Differently however from consumption of print, digital platforms enable a mass ceremony, in which publics are not simply silent consumers of a national narrative spread by novels and newspapers. Being simultaneously products, producers, and consumers, digital platforms allow the collectivity to interact, cocreate, produce, and consume white racism, and at the same time practice white pride—an overlap between the intimate, affective, and political that Maly (Reference Maly2020) calls metapolitical intimacy. Intimacy here is not just produced metaphorically. Through the inclusion of people in an imagined collective readership, it is practiced through co-presence and co-creation as well as through a rearticulation of the public and private distinction which centers the mundane, the authentic, and the affective as central political aspects around which the rebirth of the white nation needs to be organized.

We explore Laura and Jody's branding activities to understand how platform capitalism is put at the service of PA's metapolitical project, that is, how it helps normalize fascism as an object of daily consumption and practice. PA's practices of interconnection, circulation, and value generation are mediated by a digital infrastructure, which adds value, engages audiences, and guides people's attention towards several types of marketable and ideologically laden content, as well as towards specific forms of participation in, and practicing of, a political project aiming at insuring the reproduction of racial hierarchies and the preservation of the white race.

Data and methodology

We focus on three data points: white nationalist branded products, livestreams, and Telegram messages produced by Laura and Jody. Laura runs a tea company called Grandma Towler's, as well as a weekly livestream called Tea Time with Sam and Laura. Jody is responsible for Clean and Pure soap and a weekly musical livestream, using the handle The White Butterfly. While the funding records for livestreams are private, Laura openly admits Grandma Towler's profits fund PA. Their ‘about’ web page clarifies this is a commercial and an ideological project, whose profits go to ‘projects that help our people and communities’.Footnote 4 These entrepreneurial practices build an online and offline community of white pride, while also creating value and earning profit, which supports the organization and its political activities.

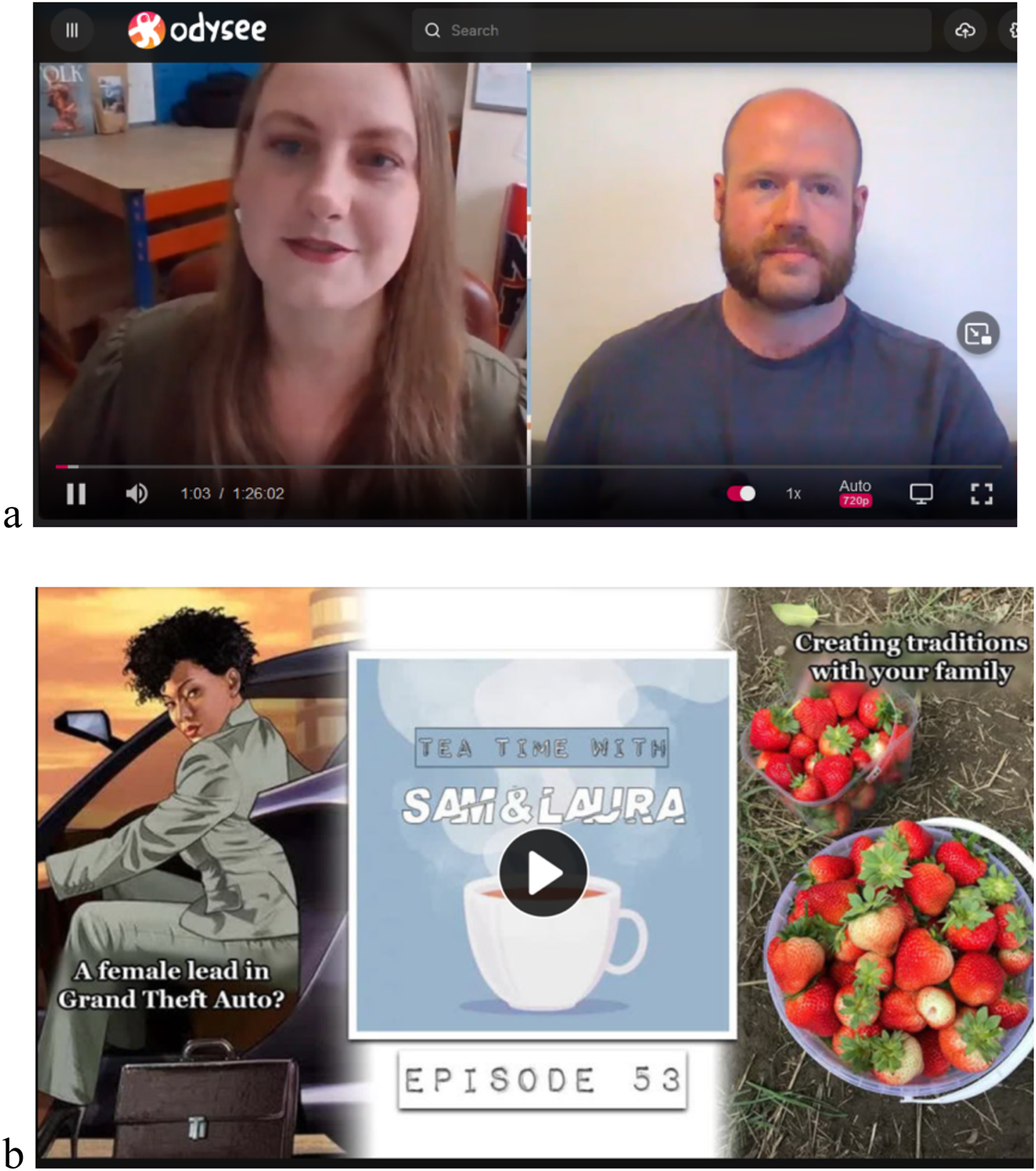

Our digital data set centered on the PA website, their racist activist website We Were Never Asked, and the business websites of Grandma Towler's and Clean and Pure, as well as other linked sites for racist brands or organizations (e.g. Mighty White Soap, White Art Collective). As authors, we viewed together and discussed selected video streams uploaded by PA, Jody Kay, Laura Towler, Sam Melia, and Mark Collett on YouTube and Odysee in 2022–2023, and six months of posts gathered during January to June 2022 from the Telegram channels of Laura, PA, and Grandma Towler's, with follow up in April–June 2023. This resulted in a corpus of 300 Telegram messages, 200 hours of video streams and comments, and forty web pages (see the appendix). While all data is publicly available, authors were careful to never like, subscribe, or promote any content as to do so would be to participate in the monetization of this ideology. This also included not watching a full video in Odysee to avoid monetization.

Like other work in digital linguistic anthropology (Delfino Reference Delfino2021; Divita Reference Divita2022; Tebaldi Reference Tebaldi2020, Reference Tebaldi2024), here we bring together Peircean semiotics with work in language and political economy (Duchêne & Heller, Reference Duchêne and Heller2012; Del Percio, Flubacher, & Duchêne Reference Del Percio, Flubacher;, Duchêne, Garcia, Flores and Spotti2016) to explore digital discourse and platform capitalism (Papadimitropoulos Reference Papadimitropoulos2021). Particularly, Nakassis’ semiotic analysis of intertextuality in branding (Reference Nakassis2012) is extended to Gal's (Reference Gal2013, Reference Gal2018, Reference Gal2019) analytical framework on the moral saturation, circulation, uptake, and transformation of meanings and Tebaldi's (Reference Tebaldi2023) semiotics of naturalization, the semiotic processes through which fascism is made to seem meaningful, natural, desirable, or true. Foregrounding platform capitalism in political organizing and fascist meaning making (Tebaldi & Gaddini Reference Tebaldi and Gaddini2024; Tebaldi & Del Percio Reference Tebaldi and Del Percio2024), the analysis offered here examines how digital platforms shape practices of production and consumption of fascist ideologies, frame participation and interpretation, and enable monetization.

Specifically, in three intersecting analytical steps, we explore how PA mobilizes digital branding techniques to (i) build affective investment in whiteness by making tea or soap a defense of a white British community; (ii) build community and spread their ideology to a broader audience; and (iii) interconnect their political, personal, and brand media in order to regiment the public's interpretation of this community as leading the battle against the great replacement.

Branding conspiracies and communities

We first discovered Laura Towler in an interview on Girl Talk, a YouTube channel interviewing figures associated with the US far-right ‘tradwife’ movement.Footnote 5 Here she echoes their familiar stories of a sexually threatened woman as symbolic of whiteness under threat (Tebaldi Reference Tebaldi2023), but with a British accent. A shy redhead, ignored by ‘woke’ classmates, harangued by the changing faces of a northern UK city, its diversity, its loneliness, she longs for the Yorkshire of her grandma, with its community, its warmth, and its whiteness. She calls for the violent return to the gender roles and racial makeup of 1940s UK, the forcible removal of immigrants and Jews, in language that indexes harmlessness, love, family, a return home. This figurative rebranding of fascism as community self-defense is also accomplished by Laura's literal brand—Grandma Towler's Tea.

Laura's company, Grandma Towler's Tea, funds unspecified ‘projects for our community’. Named for an imaginary grandmother, the company's branding translates the nostalgic euphemism of grandma nationalism into warm brand images: Grandma Towler's rocking chair, fuzzy woodland creatures, a cottage garden, happy families, and a warm cup of English Breakfast. And for your American guests, a cup of the Great Awakening coffee (a reference to Trumpian conspiracy). Branding both tea and fascism as grandma, it links ideology, sensory qualities, and affect in a potent example of what Gal terms ‘moral flavor’ (Reference Gal2013). Tea is already imagined as having moral or ideological qualities of being essentially English, comfort and sociability also linked to its sensory qualities of warmth or sweetness. This moral flavor of warm Englishness, here, becomes linked to fascism, part of a series of practices through which it is rebranded as a warm, sociable, white community. This branding produces both affective investment and actual profits, which go into PA's projects of building a white racial community. That is, they make it so fascism is as warm and as English as a cup of tea, and then they invite you in for a cup.

A semiotic analysis of the stories used by PA to brand and build community extends Nakassis’ work on branding as citationality and performativity (Reference Nakassis2012) drawing on as well, we argue, Gal's work on moral flavor (Reference Gal2013). Nakassis’ analysis of branding shows how the brand builds meaning, tells a story, and is performative, refracting an original, cited core narrative as a brand story. According to Nakassis, the performative, the brands’ ability to imbue an object with a specific meaning, or a story, a set of structured meanings, is always only the leading event in a larger chain of signification: any performative, any narration of a brand story cites a previous instantiation of the story it brings into being, harkening back to some presumed original moment. Moral flavor links the sensory qualities of these objects to the ideology of the great replacement. These links operate as adhesives which make the interconnection between story and object seem natural, or even necessary.

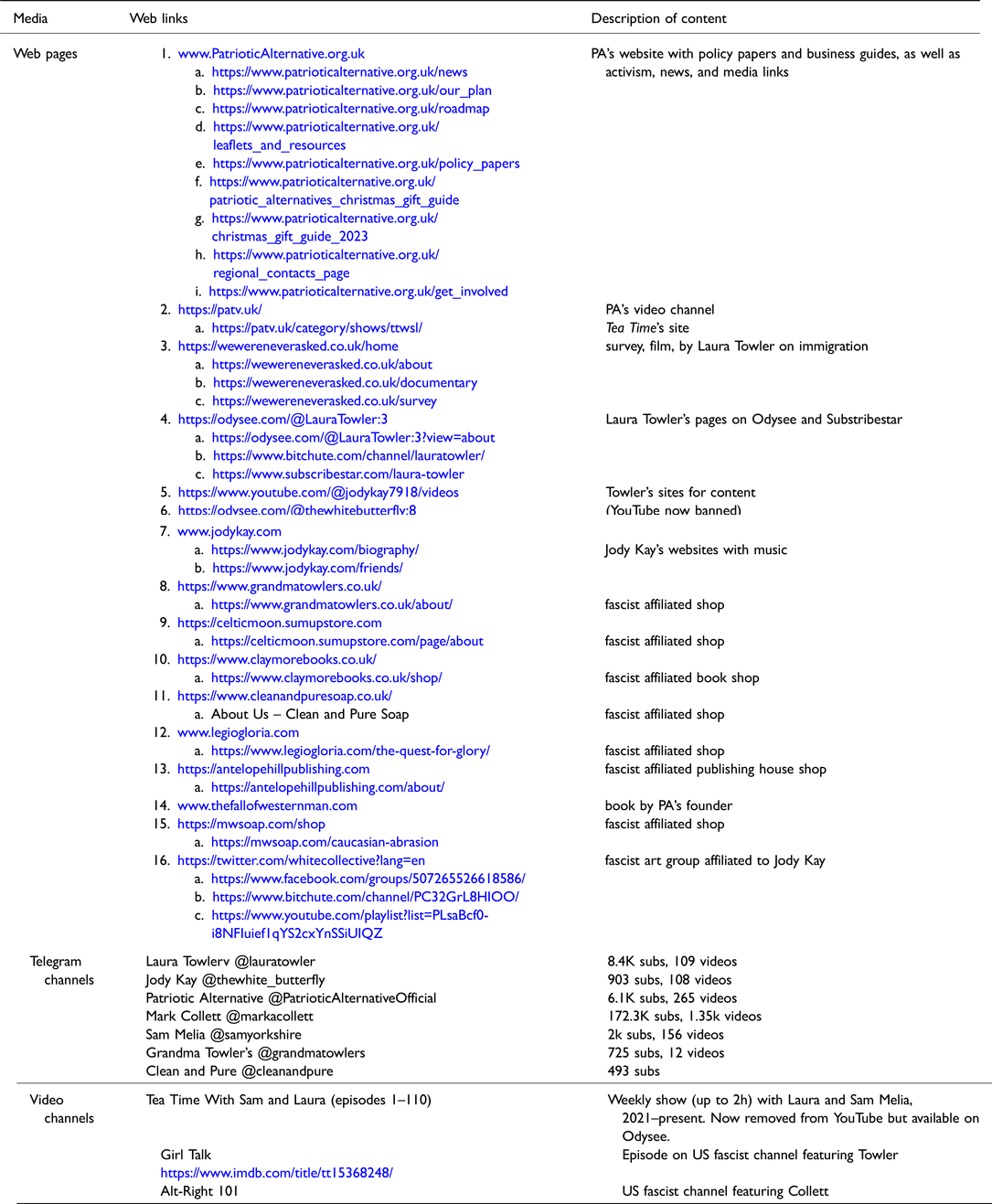

Grandma Towler's moral flavor becomes a brand story through the conspiracy of the great replacement, which represents its warmth and Englishness as under threat by immigrants and outsiders; this racist conspiracy refracted in the figure of the English Red Squirrel. This squirrel is cited (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2012), made to visually reappear, in each variant of the packaging of the Grandma Towler's tea and in all other products commercialized by the online shop, where the packaging of each object can be given more attention, as it is presented in close up, made the background, and reiterated. There, the visual becomes the main materiality to vehiculate the sensual, that is, affective quality, and ideological content that is attached to a commercialized product. The red squirrel is cute, a fuzzy little woodland creature who, on the tea, is drawn like an illustration in a classic children's story. Yet it is cited and reanimated to refer to the ideology of replacement, as it is characterized as a species native to England in danger of being replaced by the grey squirrel imported from outside England. This endangered squirrel features prominently in the branding of the tea, as seen in the bag in Figure 1a below, but is cited from their political pamphlets as shown in the leaflet in Figure 1b, drawing an explicit connection between the brand and the politics.

Figure 1. Two pictures featuring the red squirrel from PA's brand and political media.

The squirrel as symbol of this brand story frames the great replacement in natural terms. The squirrel is cited in political flyers for the group's far-right ecological activism (Figure 1b). Towler's branding across the website refers to white people as the proper custodians of the land, ‘love your country, love your countryside’ characterizing them as having the appropriate natural connection. This discourse of racialized connection to the land is eco-fascism, showing at least two of Forchner's (Reference Forchner2020) key characteristics of far-right ecological discourse: first, the animal as symbolic of conflicts between races in human society, and, second, aestheticization of nature as a symbol of nation. This suggests that the immigrant is, like a grey squirrel, inherently a dangerous outsider, threatening the red squirrel/redheaded girl with extinction. Secondly, rural areas are the true nation, associated with whiteness, similarly imagined as threatened by urbanness linked to blackness.

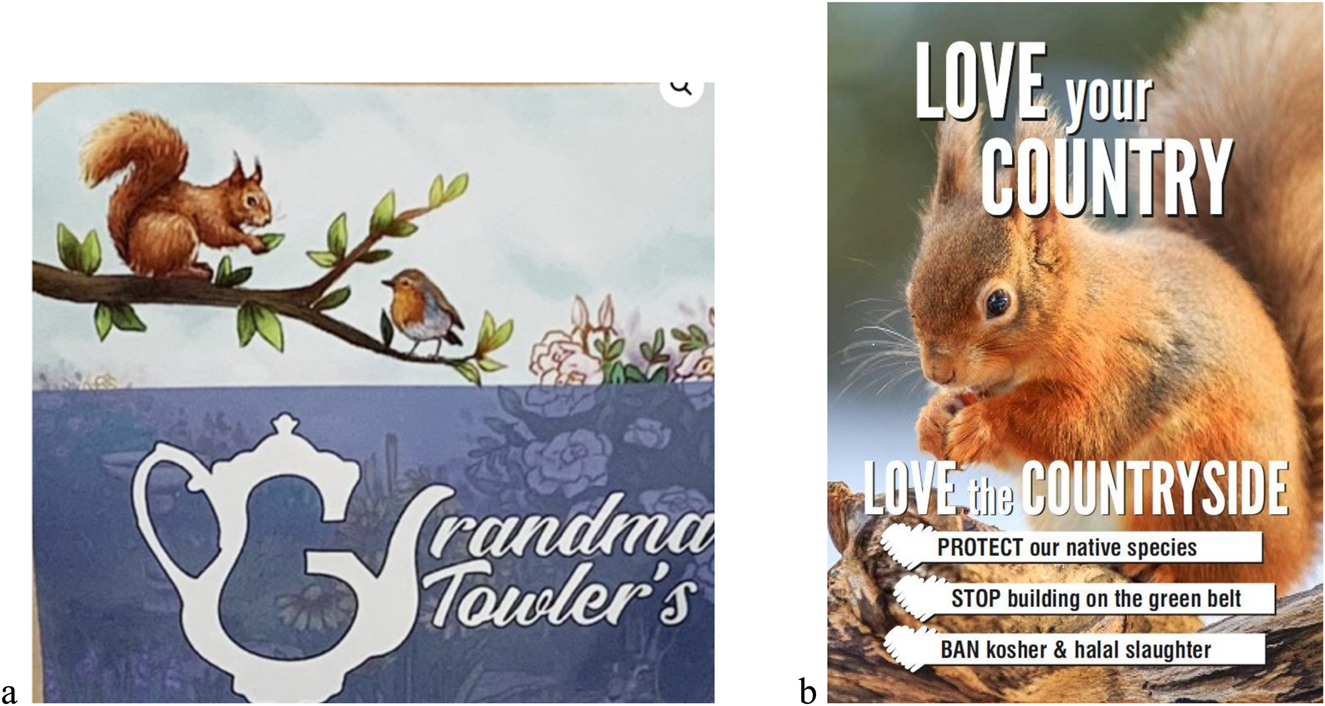

With this constant repetition, the red squirrel becomes an indexical emblem of the story of the great replacement of white Britons by racial others. This uptake is shown in a review of Grandma Towler's red squirrel enamel pin (Figure 2), left by customer RichHomeCounty (a pseudonym), and strategically displayed as testimonial to ‘show your support for all British species that are in danger of being replaced’. RichHomeCounty clearly refers to himself as a ‘British species’ in the reflexive reanimation of the great replacement conspiracy. As such, RichHomeCounty's role shifts from consumer to producer, contributing to the reinstantiation of this ideology, to its circulation and circular reattachment to the object commercialized by Grandma Towler.

Figure 2. A customer image of PA's red squirrel pin.

Circulation also happens across the products commercialized by the online shop, often through community building activities linked to the tea's branding such as cookie baking or reading. Normalizing the markedly racist reanimation of this squirrel, it is cited and taken up widely in areas not typically considered areas of fascist struggle—showing the relevance of this brand in the spread and normalization of the story of replacement. In Figure 3 below, on the left is an image from the Towler's website which shows gingerbread cookies in the shape of a squirrel, and, on the right, a children's book which asks you to count ten red squirrels. The cuteness of the squirrel and its lack of apparent fascist association (unlike a swastika or a Sonnenrad, for example) allow it to move in new spaces while also deepening its fascist meanings, linking PA's ideology to family, nature, and children.

Figure 3. Image from PA's website also featuring the red squirrel.

In both the gingerbread and the book, the red squirrel is the main character in a fun activity to do with your family or for your community, translating the story from an abstract ideological model into daily practice that one can do with ones’ children. But these are not only for children, but for the salvation of the ‘white race’ as a whole. In placing the symbol of the great replacement in a cookie or a children's book, the brand story reaches its happy end—the future white children who stop the great replacement.

Circulation also occurs across other fascist brands, through ‘Christmas gift guides’ or other PA affiliated companies such as Jody Kay's Clean and Pure soap company. Soap marketing has a long history of white supremacy from Ivory SoapFootnote 6 to the Mighty White Soap Company. Extending Eberhardt's (Reference Eberhardt2022) link of natural food and threat of disease in digital influencers’ discourses, Clean and Pure soap's healthfulness is also branded as fighting social decadence and decay. And like the tea, this soap builds a brand story of endangered whiteness using animals—here it is about the loss of bees—which also frames the English as the true stewards of the land. Each Clean and Pure soap comes wrapped in wildflower paper which can be planted to bring bees back to the countryside. This indexically links the naturalness, purity, and cleanliness of soap to the fascist ideology of cultural purity, the white body an extension of the countryside itself. These indexical links also deepen previous ways of building community around the brand, involving its users not only in the tradition of tea but in actively and practically caring for their countryside by planting wildflowers and saving endangered species and spaces. Rebranding fascism makes it as English as a cup of tea, as friendly as a fuzzy woodland creature, as natural as clean white skin, and as beautiful as a field of wildflowers. In these brands—from the name of clean and pure to the soap itself—the ideology takes on the characters of the products it sells, linking sensory and ideological qualities in a moral flavor that deeply naturalizes far-right beliefs.

Branding the right is not just about making meanings; circulation also creates a public imagined to desire these meanings. Turning the conspiracy into a narrative that is cited and made relevant in the everyday of publics willing to buy these objects also builds a public at the intersection of marketization and racism. Purchasing these products inserts one in this brand story, a hero saving the white race. White nationalists use this branding to sell, to spread, and to shape their ideology and invite others into the project of restoring the white community. In its brand story, there are threatened victims—cute woodland squirrels or towheaded babies in rain boots. This means there are also heroes who save them, beautiful women who love England and teach others to do the same, strong men who (literally) fight the great replacement. Daily practices, such as drinking tea, reading to kids, or having a cookie become tiny battles for whiteness, even fascism. These small moments of metapolitical intimacy forge links between mundane practice and the fascist project, with repetition naturalizing the connection between cups of tea and reversing racial replacement through the violent elimination of all minorities from the UK.

These meanings and practices also build a community, not just through buying these ideologically saturated products, but through the discursive space of the digital sales platform. From the citation of photographs of purchases of the tea on the website, to RichHomeCounty's testimonial about his own uptake of the squirrel pin, the website functions as a space to invite users into PA's community building project, their political vision. It is then not only the racist branding of the tea, but the website as a virtual tearoom, enabling a public's shared citational experience, the collective remembering or referencing which underpins the practice of buying and consuming, but also sharing and gifting of these objects, the building of relations, intimacy, and status. The shift from print to platform capitalism enables this multiplication of citational acts, the ability to shift consumer-producer relations from a one-to-many towards a many-to-many logic, that both allows the circulation of PA's fascism and the building of a community of hate. We explore the roles of platform capitalism in the creation of this racist public more fully in the next section on Laura's livestream, Tea Time.

Paying to play

PA builds a racist public through the production of different livestreams in which those perceived as high status in PA directly interact with its members or targeted audiences. These livestreams are audience engagement techniques very popular with video gamers and are used to build and monetize community. PA's videos are monetized on Odysee, Entropy, and Subscribe Star. On Odysee, a streaming platform, videos earn in three ways: earnings per view, tips or direct donation, and site or app promotions (Leidig Reference Leidig2021). Odysee's anonymous, decentralized bitcoin-based funding structure and lack of content moderation (and demonetization), rewards extremist groups. Streamers use Entropy to create paid live chats; for a nominal fee, viewers of a video on YouTube or Odysee can appear on the stream, ask a question, comment, and interact, paying to be part of an exclusive community. Finally, PA also uses Subscribe Star, where for a monthly fee viewers subscribe to all of PA's media, and for an additional donation (higher tier) can gain access to special content.

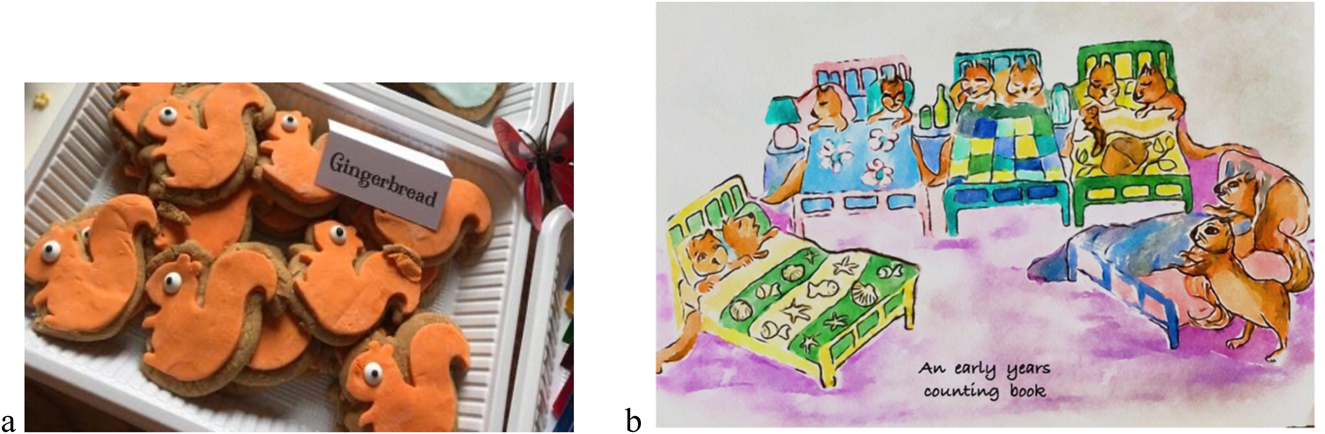

PA's most popular livestream is called Tea Time with Sam and Laura. ‘Our lifestyle show from a nationalist perspective’ is produced in Yorkshire by Laura and (prior to his incarceration) her husband Sam Melia. Tea Time reflects the culturally scripted event of tea associated with Englishness, tradition, community, and family time. The nationalist lifestyle covers topics such as family and local tradition, or playing video games or football, and makes PA's great replacement into banal nationalism (Billig Reference Billig1995), part of mundane activities which further the spread of, but also active engagement with, this very same ideology. Analysis of this stream allows us to make two points about how online streaming is invested in by this far-right organization for community building: first, it makes everyday talk part of fascist ideology, and second, it makes fascist ideology payable content.

Chosen because of its inclusion of Yorkshire Day, Episode 53 of Tea Time with Sam and Laura (streamed on August 1, 2022 on Odysee) starts with Laura introducing the structure and the ways the audience can participate in this exclusive conversation through paid and unpaid questions. Laura clarifies that the money generated through this stream goes towards ‘the cause’. Money and ideology, pride and profit are constitutive aspects of the political project that PA carries forward, building a community of white supremacists.

Tea Time usually follows the same communicative pattern. First, Laura and Sam comment on mainstream woke media and share small stories to help their audience make intertextual links between mundane events and PA's ideology and the several tropes on which this ideology relies. The stream is launched with three small stories (Bamberg & Georgakopoulou Reference Bamberg and Georgakopoulou2008) which capture a gamut of interactively constructed narrative activities. Laura, who acts as hostess, solicits Sam to add his perspective on politics: consistently linking her reports on the minutia of everyday life back to his ideology of the great replacement.

Figure 4. Screenshots from Episode 53 of Tea Time.

‘Happy Yorkshire Day!!!’ Laura introduces her first topic with a big smile adding that ‘obviously Yorkshire is the best county in the country’ and reminds the audience that both Sam and Laura are from Yorkshire, as is Grandma Towler's tea. ‘It's the best tea in Yorkshire’. In a chiron at the bottom of a screen, a discount code AYUP, and an informal greeting in the northern UK, indexes Yorkshireness and cements this association between connection to place and to purchasing tea or participating in the community. ‘What's your favorite thing about Yorkshire?’, Laura asks Sam. ‘You will laugh now’, Sam responds. ‘Probably the diversity, of the environment’. Sam here appears in our view to be, first, ironically using discourses of diversity to celebrate whiteness, but then further indexically linking a Yorkshire accent (and therefore a presumed local identity) to nature as he goes on to clarify: ‘We have got coasts, we have got some mountains, or hills…We have got such a wide range of places to be where you can be still in Yorkshire what I really enjoy, also the range of accents in Yorkshire as well, there is quite a lot of diversity in those regards as well’. Sam's discussion of the diversity of Yorkshire mobilizes again a discourse of endangerment which, like the branding of the red squirrel or bees, uses aestheticized nature to mobilize the language of diversity for those who are against it.

Laura introduces the second story, with the ordinariness of a woman speaking to her husband about that most masculine of pursuits: ‘We won the football, I wanna say we, I mean, English people won the football’. Laura then explains that she doesn't like football, however explains: ‘The two arguments for diversity, the diverse English football team lost and the homogeneous English football team won’. Here she opposes England's racially diverse national male team, which had recently lost, and the majority white English female team, which won the European championship. Facetiously, she asks if there will be any articles saying ‘homogeneity is our strength but I did not see any, what's going on Sam?’. Laura points to the celebration of diversity in football, and the invisibilization of homogeneity, linking even the most mundane to anti-white bias. ‘Surely the media are impartial’, she adds with a laugh. Laura manages to bring the smallest daily event back to the story of white endangerment by media elites pushing racial replacement. The discourse of white endangerment passes quickly to a call to racist activism: ‘Next week on Tuesday it is indigenous people day, so we have eight days left…’. She then displays an email address featuring ‘White Lives Matter’ to which participants and the wider PA community are invited to send their pictures of their indigenous day banners. ‘Please do something we are looking for quantity’, she insists. Laura then makes suggestions which again connect fascism to everyday life:

Last year, we got people who were out on hikes and just took a piece of paper and held it up above their face when they went out on a hike.…There are lots of people who are already involved, lots of people are going to get involved in their regions, but please do something, everyone listening can contribute, because you can do it completely anonymously, you can do something in the garden, you can bake something at home.

Laura closes this part of the stream by reminding the audience to send in their pictures to be shared on PA's several social media platforms.

In this stream, PA's public is instructed to link Yorkshire Day and the celebration and care of the nation and oppose it to public failure to celebrate whiteness in the case of the football team. In these small stories, PA becomes a metonym for the ‘true British public’ while the stream links the ideological content it propagates with everyday life, shaping not just the way members are invited to understand and conceptualize the worlds surrounding them, but also in the way they experience and practice them on a daily basis, with their families and friends.

PA makes racist ideology everyday practice, and it makes this ideology payable content. The stream monetized PA's ideology through paid views, direct donations, product advertising, and the participation that Sam and Laura solicited. Participating in the livestream, liking the video, and rewatching it on the social media platforms generates money for Laura and Sam through an algorithmic system which links clicks to watched ads to a revenue system. Members pay to share their content, or to ask a question on the livestream with Entropy, the link to which is prominently displayed. While questions with no donation do appear in the chat, those without money are seldom commented on or picked up by Sam and Laura during their streams, while those who donated are explicitly picked up by Laura and complimented. If participation in this community comes with a price, monetization is not the ultimate or only goal. Paying for participation means becoming visible in the community, displaying commitment and getting recognition from the community. Monetization means creating active participation, and status in the community. Profit creates white pride.

Allowing audiences to directly engage with Sam and Laura builds relationships and intimacy, but also status and recognition. The interactive portion always follows the same script, as in these examples from Episode 53 where Laura rewards payers by making their questions visible.

58.40 Laura: Pie donated three pounds and said heyo here is the Yorkshire god's own country - Thank you very much, Pie happy Yorkshire day to you as well!

01:00:16 Laura: Ullrich donated 20 pounds and said considering the articles I read about the changing workplace culture at rock star I think GTA6 is really likely to be liberal progressive they don't want to punch down anymore much like the original CD project left where the original staff has left.

Following this larger donation and more extensive comment, not only does Laura thank them, but Sam reacts as well and engages with the punching down aspect of Ullrich's comment. Participation in PA's struggle is not exclusive to people living in the UK; funders come from transnational white nationalist networks interested in PA's mobilizing strategies. This includes US anti-gender mobilizing groups interested in PA's anti-drag queen protests, the White Arts Collective, and US Americans with English roots. This shows how, for PA, racial identity is local, but racial replacement needs to be fought on a larger scale.

56.32 Laura: We have a question from XXL Johnson for 5 dollars who says: this is 5 dollars just for the new placard my favorites are the parents shielding their children against the LGBT rainbow and learned ABCD not LGBT excellent work Laura - Thank you for that.

Sam contextualizes and elaborates.

58.48 Laura: Carlotta donated 10 euros and said would you consider playing the song of Livia Kee in the intro of the next Tea Time her music is on YouTube

Sam: oh yes definitely this song is really good

Laura: yes we want to play nationalist musicians.

01:01:37 Laura: Robby Herbet donated 5 US dollars and said dear Laura I just checked at the Yorkshires and my grandfather's shield … has two petals and one leaf on the top so your flag may be upside down … Thank you for that donation.

Laura's Tea Time enables audiences to become visible, show alignment with PA's values, share their own experiences and get recognition, generating future content. Viewers are sometimes invited as guests to actively contribute with Laura and Sam to Tea Time and present their ideas and projects. Streaming platforms are ideal to shape this sort of participation and value creation. They enable affective attachment through their interactional nature, the illusion of immediacy and intimacy, and the direct accessibility that they create. They allow a direct engagement with audiences: not mere ‘prosumers’, consumers which are also producers, but rather a collapsing of these opposites into a sense of togetherness and joint commitment towards a shared cause, or common affective commitment—a community whose comments and participation become part of the product. The participatory element of these streams deepens affective engagement; metapolitical intimacy (Maly Reference Maly2020) is also monetized. They build a transnational network of white supremacist activists, what PA calls a white digital ‘tribe’, which also gives them status. In the following section, we explore further how this tribal network is linked and interlinked to build community and regiment the message.

Regimenting the message, extending the community

PA's digital marketing emphasizes the interlinking of brands, websites, and social media; Gal (Reference Gal2018) calls this management of links between people, things, and discourses the social organization of interdiscursivity. It links and organizes not only discourses and registers but also the societal arrangements that are constituted around registers, people, objects, events, practices, and through which registers have their powerful effects of connection (and separation) in specific historical moments. We add that linking, as a practice of interdiscursivity, is a process of directing and guiding audiences through interconnected contents. Linking is facilitated by the nature of the digital platforms which can be made to interconnect through the embedding of links, pictures, and references that link the user from one platform to another, for example, from Twitter to YouTube, but also help the user link pieces and bits of disconnected practices of signification (disconnected posts, pictures, and videos) to form a cluster of interconnected and seemingly coherent meaning (e.g. a brand image).

Along these lines, PA uses linking for two important and interlocking functions: directing audience attention back to their products and events and the community they create, and regimenting audience uptake or interpretation back to their core message of the great replacement. That is, they link the viewer to the branded products and the channel, the channels to each other, and everything back to the pro-white ideology and the larger chain of signification that this ideology stands for. Everything must come back to the story of the threatened white Britishness with its desirable moral flavor. It must invite the user to join in an actual cup of tea and assure that the meaning of tea is steeped in racial hatred and white nostalgia.

PA uses Telegram, an alternative messaging platform. Telegram users can have channels to broadcast messages to subscribers. PA's 5,456 subscribers can also interact and communicate, gaining status if they are reposted by PA leaders such as Laura, who has her own 8,101 subscribers. Brands also have their own channels: Grandma Towler's has 824 subscribers, while Clean and Pure soap has 481. Inter-channel links can extend the audience beyond these subscribers and a popular post will have several thousand views, always directing all these users back to PA's core message with different intertextual links: Telegram messages channel audience attention to videos produced by Laura, Sam, Jody, or other members of PA or fascist networks, from the PA brand to other brands promoted by white nationalist actors, from the PA brand to PA's community building activities.

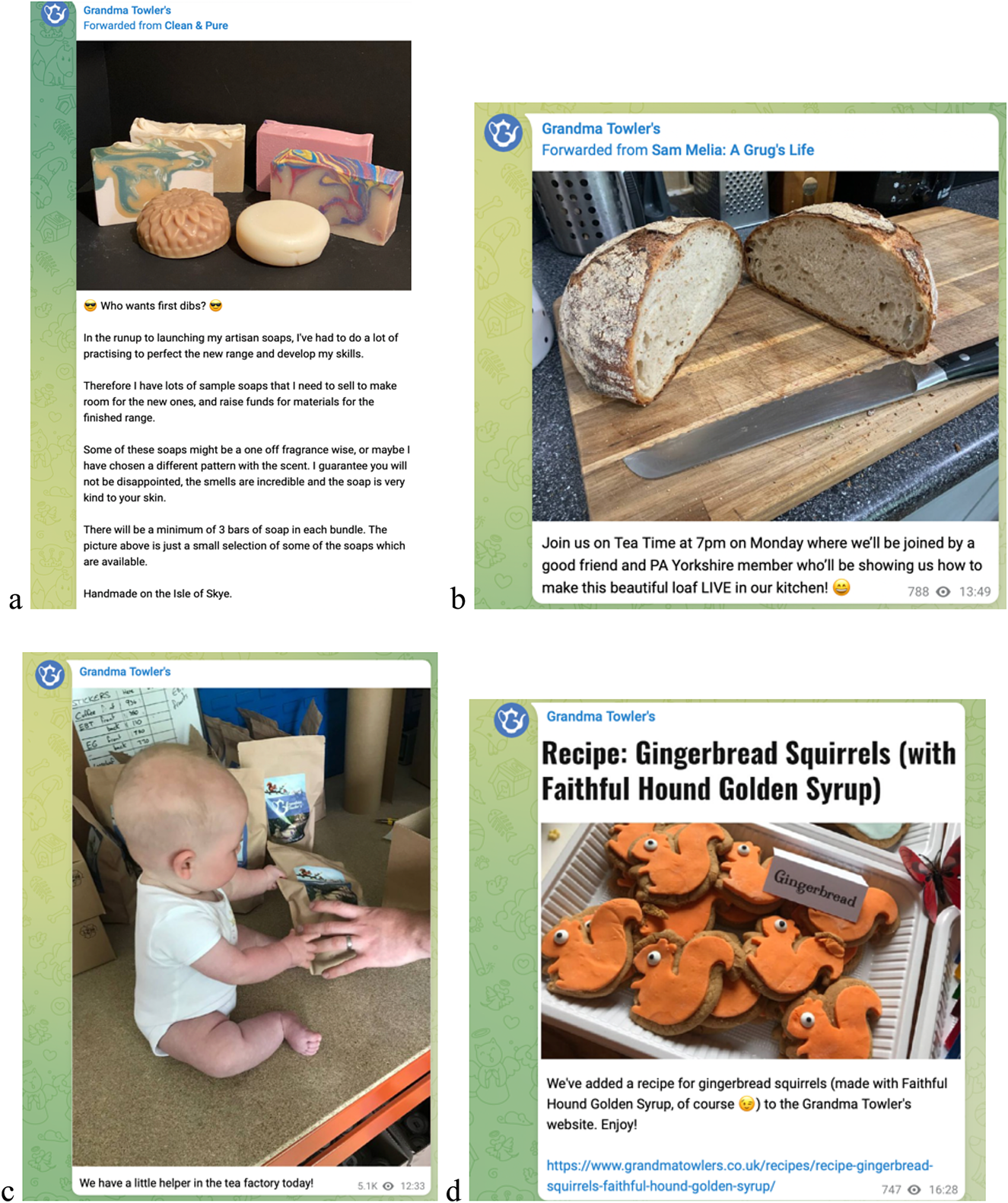

This type of interdiscursivity is also used within the Grandma Towler brand channel. Through forwarded messages, mentions, or linked images, intertextual links with other nationalist brands, the political activism of PA, and the personal life of Laura Towler are created.

Grandma Towler frequently reposts images from other brands, in particular Clean and Pure as shown in the top left in Figure 5a above. Towler reposts this, linking these two with others such as the ‘Faithful hound honey’ mentioned in the middle post above. White business community is strengthened by posts like the ‘keep it folkish’ list or the Patriotic Alternative Christmas shopping list, which list several small businesses aligned with what PA describes as indigenous British values. These contribute to the building of an imagined true British public, but they also sell participation in it and provide users the possibility to buy from a chain of businesses which is aligned with their ideological positioning and therefore integrates political participation and activism with practices of consumption.

Figure 5. Images from Towler's telegram showing the reposting of both personal and brand accounts.

Telegram reposts show an intentional integration of political action and economic activities, done to shape users’ affective investment in whiteness as much as economic investment. Telegram reposts create intertextual links not only to PA videos or to brands, but to the person of Laura and to the white community they want to build. For example, the Telegram chat recycles the images of the cookies, citing the threatened red squirrel (in Figures 1 and 3) linked to the Towler's brand but also shares a cookie recipe with indexical links to family, sweetness, as well as her brand story. This is even clearer in the most popular of Grandma Towler's posts, when Sam and Laura show their baby with the tea emphasizing the family and the brand story of the white community. Food, community, video, and the Towler brand come together in the final post (see Figure 5d). Forwarded from Sam, the owner's husband, this indexes family and shapes the way the teatime video is taken up—again, as part of the community. This is further shown by the loaf of (white) bread and the message showing that a friend and PA member will share recipes, both reflecting the show's nationalist lifestyle and building friendship around membership in PA. These intertextual links create a regenerated white community online.

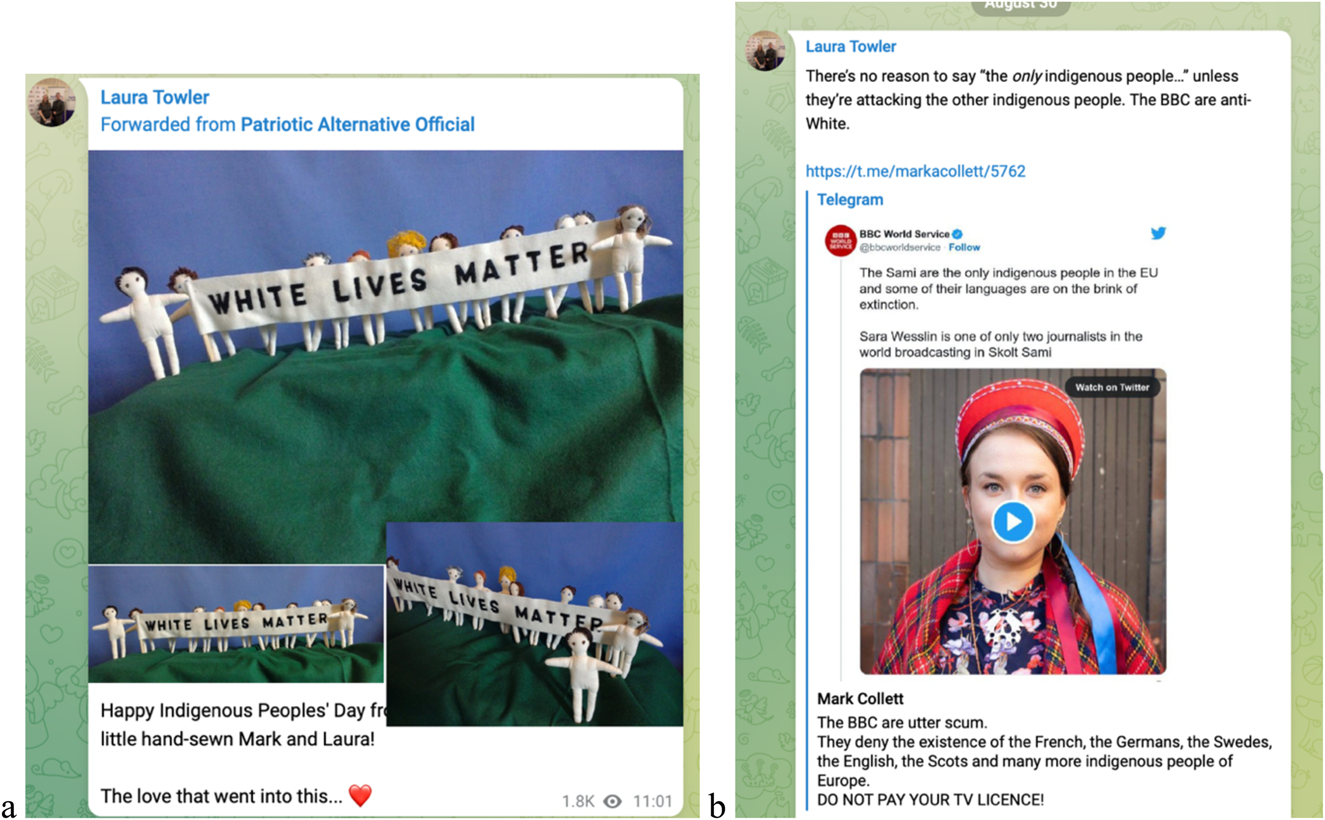

Towler's nationalist lifestyle show and her Telegram regiment the meaning of everyday actions back to the core message of whiteness under threat. This is a key function of these intertextual links, both building an online community and bringing this community back to the core message of the great replacement. In Figure 6 below, two Telegram messages from Towler's personal account link the Telegram of PA and the Telegram of its leader Mark Collett. These clearly show the ideological effects of the interdiscursive links Towler is trying to manage, the first one linking to their very frequently cited slogan ‘white lives matter’ which again links the idea of white community and takes up and twists the discourses of diversity to fight for white pride. These discourses of endangerment are reiterated in the caption ‘happy indigenous people's day’ clearly signaling here white people are indigenous and deserve to be celebrated, but are also endangered, threatened with racial replacement. Yet this narrative of threat also invests this whiteness with affect, from the heart emoji to the ‘love’ that went into a ‘hand sewn’ doll indexing traditional craft.

Figure 6. Photos from Laura Towler celebrating indigenous people's day and showing the regimentation of all their media to this message.

Figure 6b illustrates one of a quite common post genre, showing what PA characterize as anti-white bias in media (indeed there was a whole video contest called ‘what is anti-white’), which directs the audience to interpret any event in terms of indigenous whiteness threatened by racial replacement. Here the uptake of a BBC article about the Sami on the brink of extinction is directed, first by Collett and then by Towler, as she forwards the message, to show that the article is trying to erase the fact that other white Europeans are indigenous. The other side of the white community is always the idea of white indigeneity, the co-option of discourses of endangerment in order to serve fascist politics. The linking then directs the viewers to go between the brands, videos, and personal media, but also between affective investment in white community and the racist, antisemitic conspiracy ideology underneath it.

Branding the white nation

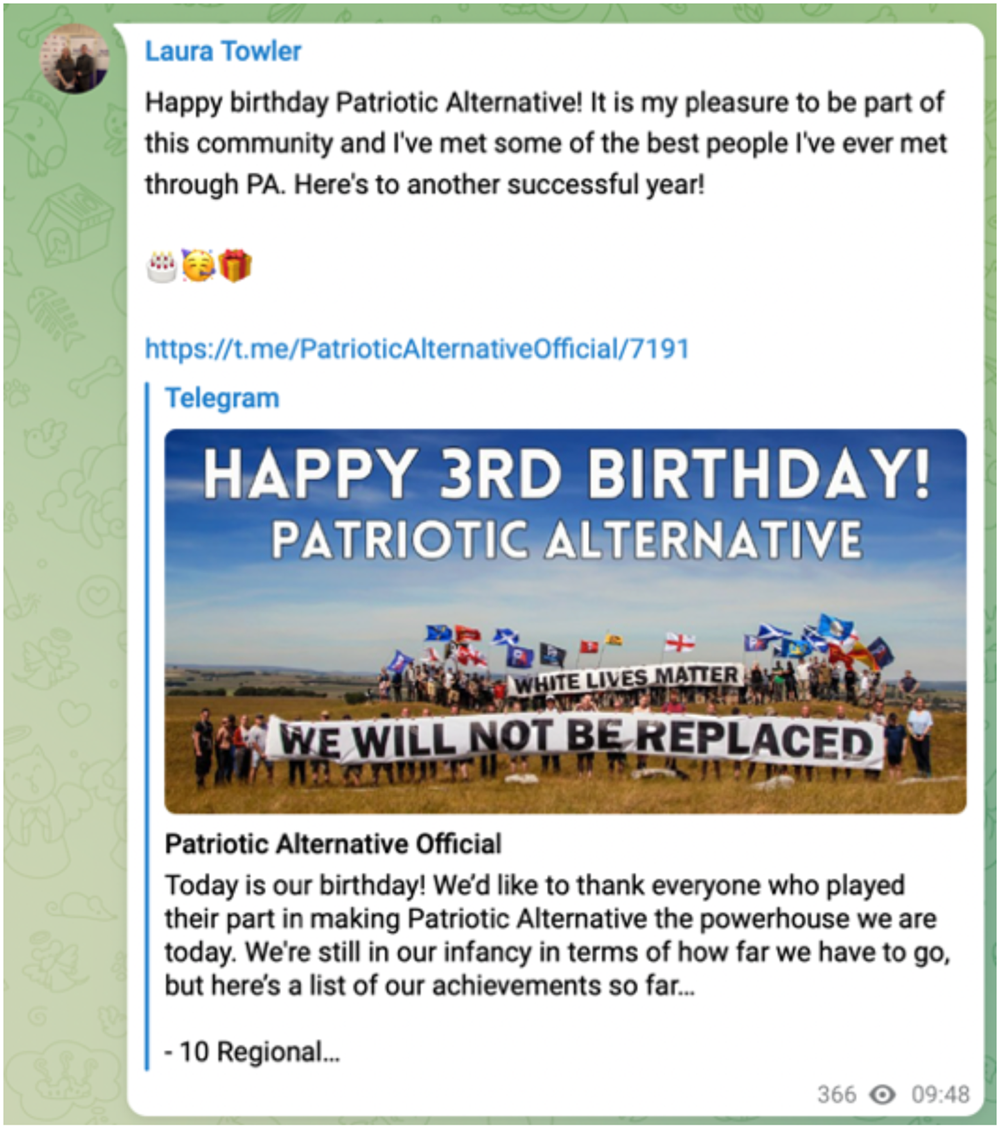

In this article we have shown that PA uses digital branding techniques to do three intersecting things: (i) branding racist meanings to daily practices, building affective investment in whiteness by making tea or soap a defense of a white British community; (ii) according status and building community to spread their ideology to a broader audience and strengthen these affective ties to white Britishness; and (iii) channeling traffic to interconnect their political, personal, and brand media, regimenting the interpretation of this community as part of the great replacement. These processes all come together in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7. Happy Birthday to PA.

The image shows one of PA's nature walks, which ends by protesting the great replacement. Here the ‘HAPPY 3RD BIRTHDAY’ in the image, as well as the bottom text voicing the organization in the first-person plural, ‘our birthday’, displays community and invites the audience in. Engagement is reinforced by Laura's friendly response, ‘happy birthday’ and emojis, while the use of ‘pleasure’ and ‘best people’ accords status and affective attachment to members. Finally, everything regiments uptake back to the core message—fighting the great replacement, for a white nation.

As we demonstrated, this story of replacement is branded and circulated through three central processes: (i) the branding of fascist metapolitics with enregistered emblems of the grandma and the endangered squirrel, (ii) the invitation to participate in this brand's white tribe through digital platforms, and (iii) the management of interlinking platforms and accounts which build community, support the economy, and regiment the message. Every message, every like, every click, every purchase comes back to fighting for whiteness.

Beyond the normalization of far-right discourse, the spread of a racist message into mainstream channels (Wodak Reference Wodak2020), PA's branding is a metapolitics aimed at cultural and political power for white Britons. Their metapolitical use of mundane semiotic elements and practices is a metapolitics with three core elements: a discursive co-opting of discourses of diversity which rebrand fascism as white community, economic support for this community and organizing, and promotion of affective investment in far-right narratives and forms of personhood (Tebaldi Reference Tebaldi2023) which invites further participation in these communities. Fascism branded as community is not just normalized, but made more powerful, more profitable, and more totalizing.

Digital platforms allow for the building of this total fascist brand (borrowing from Urla Reference Urla2012) and a public imagined to desire it. PA's use of platform capitalism, as an intensification of Anderson's (Reference Anderson1983) imagined community, offers an alternative—that is, white—platform for both economic and intellectual entrepreneurship: the branding, circulation, and uptake of fascist ideologies to build intensified interconnection and shape a fascist community. In a fascist version of Duchêne & Heller's (Reference Duchêne and Heller2012) pride and profit, the propagation of fascist ideologies and their marketization do not constitute two opposites but two intersecting parts of the same process of community-making, a community of hate which battles for the reproduction of the white race and the perpetuation of white superiority. They brand a white nation.

Fascist ideology remains at the center of their marketing and their community itself. Behind the marketing, the soothing sounds of pouring tea, a cup sipped by a well-dressed actress, or the beaming smile of Jody Kay is the ideology of hate spread into increased circulation, into all the most minute elements of everyday life, into the most affective moments, into the economic activities which sustain it, into all the domains of action around which a community is built. At no point is this clearer than in Jody Kay's stream ‘The White Pill – this is why we do what we do’. As she chats, she glowingly reports that she met a man in PA. A first audience member pays to respond ‘14’ and every audience member responds in kind. A glowing Jody reads out a paying chorus of 14's in a refrain. Not congratulations, just the neo-Nazi shibboleth 14 standing for: ‘We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children’. Every moment from teatime to weddings is regimented by this fascist message. She must circulate these discourses, these products, to build the strength of the white nations brand. But this is ultimately so that she will fall in love and have children, to ensure the strength of the white nation.

Appendix: Table of sites