Introduction

Proposals to change the institutional features of national high courts have been on the agenda recently in the United States and Israel in ways citizens of neither democracy imagined at the start of the 21st century. The 2020 presidential election in the United States had former government officials and Democratic primary candidates calling for measures to add justices to the United States Supreme Court (USSC) and end the life terms of its politically appointed justices (Phillips Reference Phillips2020). Public opinion polls conducted at that time showed substantial support for such measures (Marquette Law School Poll 2020; Braman Reference Eileen2023a). Last year calls to change that institution were renewed amid charges of judicial ethics violations. On July 29, 2024, former President Joe Biden asked Congress to consider passing legislation that would effectively end life tenure on the USSC and impose an ethical code for its members (Howe Reference Howe2024). The recent election of President Trump and Republican majorities in both houses of Congress suggest officially sanctioned alterations to the USSC may be on the wane. Still, public sentiment about ethics violations and concerns that current Supreme Court justices are fundamentally “out of step” with society continue to fuel calls to change the institution.

In Israel, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s ruling coalition has proposed three measures that threaten the authority and independence of the Israeli Supreme Court (ISC) since taking power in January 2023. The first proposal involves allowing a majority in the Israeli legislature (the Knesset) to overrule high court decisions; the second would give the coalition government control over the judicial selection committee, essentially changing the court’s current method of merit selection to a more political process. In July of 2023, the governing coalition succeeded in passing its third proposal, limiting the ISC’s ability to strike down state action under the “reasonableness” standard that the high court employs to review the appropriateness of state action under the nation’s framework of Basic Laws. At the start of 2024, the ISC overruled this measure, setting the stage for an institutional showdown with the current coalition governmentFootnote 1 (see, Sommer and Braverman Reference Sommer and Braverman2024 for a comprehensive account of recent events in Israel surrounding changes to the ISC).

Although proposals to change the institutional features of the ISC and USSC arise within disparate political circumstances, in each nation such measures came to prominence and should be considered in the context of democratic governance. Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, made it clear in the November 2022 elections that he believed the rulings of the ISC were an obstacle to officials seeking to advance the interests of Israel’s citizenry. He made it clear that he would be seeking to restrain the power of the Court. Indeed, this was a major element in his campaign, which also facilitated the creation of his coalition government. In the United States, most recently it has been Democratic politicians arguing that the conservative leaning court is out of touch with society and that measures must be taken to curb the substantial imbalance in the Court’s membership caused by Republican presidents appointing a disproportionate number of life-term justices over the last half century. Although these latest proposals to change the USSC have come from the Democratic side of the aisle, Republicans have historically shown a good deal of concern about judicial activism (McMahon Reference McMahon2011), prompting their own calls to change institutional features of the USSC not so long ago (see for instance, Zezima Reference Zezima2015; Badas Reference Badas2019 discussing Republican proposals to change the Court in the early 2010s).

In both nations, political elites have sought to convince citizens that the proposed institutional changes to the high courts are in the public interest. Political scientists have long been interested in the concept of judicial legitimacy, or the extent to which citizens are willing to protect judicial institutions from threats from other branches of government. Starting thirty years ago, Caldeira and Gibson (Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992) developed the measure that has been widely utilized in capturing the concept. Both the measure and the concept have been refined by those authors and their colleagues over the years (e.g., Gibson Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2016). In Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009, Gibson and Caldeira introduced “positivity theory,” arguing that the source of citizens willingness to protect judicial institutions lies in the democratic functions they perform. They posit that strong socialization in the United States, accompanied by periodic symbolism reinforcing judicial norms (Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014), keep most citizens in the US resistant to the idea of altering courts in light of threats to their institutional integrity.

In the last several years, however, there has been substantial disagreement among scholars about the durability of such loyalty considering growing evidence that disagreement with the substantive policy outputs of the court can diminish citizens’ wiliness to protect the institution (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013, Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015). Most of this research relies on extant measures of the concept which was developed many years ago when concrete threats to national high courts were not on the agenda in the way they have been lately. Only recently has research on institutional change to the USSC involved concrete proposals to change the institution suggested by political elites (Badas Reference Badas2019; Braman Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b).

As part of this research, Braman (Reference Braman2023b) draws on insights from prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981, Reference Tversky, Kahneman, Hogarth and Reder1987) to think about how citizens respond to calls for change to democratic institutions. Prospect theory suggests that under conditions of uncertainty, people tend to be risk averse when they are thinking in terms of gains, and risk seeking when they are thinking in term of losses. Positing that change to governing institutions involves substantial risk compared to maintaining how those institutions currently operate, Braman predicts that individuals who are thinking about institutions in terms of the benefits they provide should be resistant to change, and those who are thinking in terms of losses will be more supportive of proposed changes to governing institutions.

This inquiry adds to such thinking by employing the concept of endowment effects, a corollary of prospect theory, to explore how people think about benefits from high courts. In doing so, we contribute to the literature in several respects. Specifically, (1) we explore how people think about the benefits from high courts in two national contexts, Israel and the United States. We also (2) test how feelings about benefits from those institutions shape support for concrete measures to change those bodies in each country. Moreover, in doing so, (3) we employ a unique comparative experimental design that allows us (4) to distinguish the relative importance of democratic functions high courts perform and substantive policy gains (or losses) citizens may perceive from individual case outcomes in a novel manner. In developing our theoretical expectations, we attempt to be mindful of important differences across each national context. Our goal is to improve our understanding how citizens think about important issues pertaining to national high courts in both nations.

Benefits from high courts, endowment effects, and thinking about institutional change

Endowment effects, widely influential in behavioral economics, involve the tendency of individuals to demonstrate a reluctance to part with something that they currently possess. Kahneman, Knetch, and Thaler (Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1990) showed the phenomenon with a clever experiment where they found students who were given university mugs and pens at the outset of their study required more to sell those objects than similar others were willing to pay to acquire them. The research illustrates there is value in possessing an object over and above the value of that thing itself.

Obviously, high courts are not objects, but complex institutions. Research in behavioral economics, however, demonstrates that thinking about endowment effects can apply to public goods as well as private possessions (Bischoff Reference Bischoff2008). Moreover, thinking about how endowment effects may shape thinking about governing institutions can provide interesting theoretical insights. Let us say, for instance, that there is a nascent institution that has the potential to provide benefits to citizens, but that the institution is vulnerable to threats by political actors unsure of how it could threaten their authority. Particularly, we propose thinking about the bourgeoning powers of the European Court (EC) in the 1990s as an example of how endowment effects might shape thinking about institutional change. At a time when the EC was announcing European rights that could be enforced against member governments, several sovereign states questioned whether it should have such powers. Some European citizens were likely more aware of the rights provided from the EC than others. Considering the situation in light of endowment effects suggests that informing European citizens about rights they possessed pursuant to pronouncements of that court would make them more resistant to attempts to change the institution than citizens who were not aware of those rights. Those pronouncements, in effect, might act as a type of endowment for citizens, causing them to value the institution more than they would otherwise.

Applying this logic to national high courts, we designed an experiment to test the idea that individuals value institutions more when they are told that those institutions provide them with specific benefits than when they are not told that the institution bestows benefits. Obviously, most citizens probably have some conception of the role of high courts play in their society; the question is whether hearing about case decisions will influence those views. Of course, there is already research demonstrating that hearing about individual decisions can prompt citizens to be more (or less protective) of the USSC (Bartels and Johnson Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Strother and Gadarian Reference Strother and Gadarian2022), but we highlight that there are scholars who question why this should occur – why a single case should influence general orientations citizens have about protecting judicial institutions (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2016). Endowment effects provide a theoretical explanation that is consistent with such findings; hearing about individual cases that bestow subjective benefits may cause people to place greater value on high courts such that they are more willing to protect those institutions from threats.

Another important issue that our design addresses is the relative importance of the different sorts of subjective benefits decisions of high courts provide in shaping citizens’ valuations. High court pronouncements can provide democratic benefits, as when the court protects the rights of citizens or ensures government officials act within the bounds of their authority. Decisions can also provide substantive policy benefits, as when the high court makes a decision in favor of a litigant that citizens particularly favor. Sometimes decisions create democratic and policy benefits that work consistently in the minds of citizens. Other times they can conflict; consider an instance when a court upholds free speech rights of pro-choice or Second Amendment advocacy groups, with which citizens can disagree. As set forth below, observing the difference between participants’ benefit assessments where they favor, and disfavor, particular policy outcomes can help us understand the relative importance of democratic versus policy benefits. We also thought it would be worthwhile to explore if citizens value some kinds of democratic benefits over others. Do individuals tend to value decisions that confer specific rights on citizens more than they value decisions that keep government officials in line, or do they value these different types of decisions equally?

A related issue is whether citizens’ thinking about benefits and/or harms bestowed by high courts influences their support for institutional change. Theorizing that changes to governing institutions involves a substantial degree of uncertainly in terms of (1) who will be in control of those institutions at any given time, and (2) how changes will operate to influence outcomes once they are implemented, we believe prospect theory can contribute to our thinking about how citizens think about change. Those who see high courts as providing substantial benefits should be thinking in the domain of gains with regard to the institution, and therefore resistant to change. On the other hand, those who see high courts as causing more harm to themselves and society should be thinking in the domain of losses with regard to the institution, and therefore more likely to support proposals for change.

Scholars in behavioral economics have offered competing explanations for why people tend to be risk seeking in the domain of gains, and risk averse in the domain of losses. Tversky and Kahneman (Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981, Reference Tversky, Kahneman, Hogarth and Reder1987) famously argued, “losses loom larger than gains,” suggesting that there is a basic asymmetry in the subjective experience of winning versus losing: it hurts more to part with something of value than it feels good to acquire that same object (see also, Plous Reference Plous1993). Other scholars, including Larrick (Reference Larrick1993) have suggested “regret theory” as the reason about 80% of the population falls victim to such biases; we avoid loss to prevent thinking of our “future selves” as less satisfied and/or secure than we are currently.

Critically for our purposes, prospect theory has not only been applied in political science to how political issues are framed (e.g., Quattrone and Traversky Reference Quattrone and Tversky1988; Druckman Reference Druckman2004), but also to explain politically relevant behavior of both citizens and elites, considering their evaluations of the current state of affairs compared to some hypothetical future state in light of uncertainty (see, Mercer Reference Mercer2005; Vis Reference Vis2011 for reviews). In her Reference McDermott2001 book, for instance, Rose McDermott theorized that the reason President Carter undertook the perilous military plan to save Iranian hostages in 1980 was because he was thinking in terms of losses: inflation and gas prices were high, there was a national energy crisis, and he was behind in the presidential election. The plan, as it turned out, was a failure, costing many American lives, putting Carter in a worse position than when he started. McDermott argues, that when he made that risky decision, however, he was trying to improve his losing position. Similarly, we posit here that people who believe high courts are causing harm to themselves and society will be more likely to support potentially risky change to those institutions to forestall perceived losses.

Indeed, Braman (Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b) provides evidence that citizens’ expectations about court outputs help to predict support for proposed changes to the USSC in line with predictions from prospect theory. The USSC, however, is distinct in several important respects. First, it is part of a longstanding constitutional democracy where the USSC has had the power of judicial review for over 200 years. Second, its justices are appointed for life by the president, who disproportionately favors jurists with ideologies that are congruent with their own. Citizens are generally aware of this bias and the power of the Court to make decisions that can influence their daily lives. The USSC has a long legacy of doing so; its potential to decide controversial matters is constantly a matter of discussion on the evening news. In such an environment it may not be surprising that citizens think about institutional change in terms of perceived benefits and harms the Court provides.

Recent events in Israel provide an opportunity to see whether and how prospect theory can help us understand how people think about high courts and potential institutional changes to those governing bodies in a very different political and societal context. Threats to change the ISC arose under extreme circumstances closely tied to Prime Minister Netanyahu. There has been a substantial public outcry among Israeli citizens where proposals to change the ISC have been more direct and imminent than recent suggestions for change to the USSC (Sommer and Braverman Reference Sommer and Braverman2024). While ISC justices are chosen by a Selection Committee via merit appointments, proposed changes threaten this particular institution. Perhaps most significantly, Israel does not have a constitution, and for less than half of Israel’s seventy-five-year history, the justices have only had a power akin to substantive judicial review stemming from the nation’s Basic Laws and articulated in judicial rulings in the 1990s.

We thought it would be useful to see how endowments and prospect theory influence thinking about high courts and institutional change in the United States and Israel, keeping in mind several important differences across the national contexts. For instance, due to merit selection, the ISC is less polarized in terms of its outputs over time. Leading up to proposed reforms, the ISC has been characterized as substantially left leaning and activist by elites, emphasizing decisions resulting in reversals of government action, although those have been few and far between. One of the things Israeli citizens are wary of is a system where outputs are increasingly politicized by granting the coalition control of judicial appointments. Alternatively, the United States already has a political system of appointment. Indeed, citizens are keenly aware of the role of politics in the justices’ decision-making. This could influence how individuals across national contexts view the benefits from high courts.

Moreover, Israel is a younger country with no constitution and a shorter legacy of judicial review. As such, citizens may be less likely to see the ISC as an institution that provides distinct personal and/or societal benefits. Alternatively, their sense of entitlement to such benefits might be less secure. Recent research on endowment effects tends to show that the duration of ownership (Strahilevitz and Lowenstein Reference Strahilevitz and Loewenstein1998; Colucci, Franco, and Valori Reference Colucci, Franco and Valori2024), and individuals’ “psychological sense of ownership” (Reb and Connolly Reference Reb and Connolly2007; Mustafa Reference Karataş2020) can influence people’s reluctance to part with items. Research shows that people who held possessions longer generally require higher selling prices to part with them. Such findings suggest perceived benefits may influence resistance to change more powerfully in the United States than Israel due to its longer history of judicial review. Finally, given the specific circumstances by which threats to the high court arose in Israel (detailed more fully in our Supplemental Materials), opposition to judicial change in Israel is closely linked to opposition against Netanyahu and the current governing coalition. As such, opposition to reform may boil down to this more basic political divide.

Comparative study design

To test these institutions, we conducted a comparative experimental design using a convenience sample of students in Israel, and a wider swath of citizen participants in the United States with an experiment performed on the 2023 Cooperative Elections Study (CES). The experiment involving Israeli students was administered to students at Tel Aviv University over two waves in June of 2023 and April of 2024 when the threat of institutional changes to the court was quite prominent. The terrorist attacks of October 7, 2023 and the onset of military action in Gaza occurred between these two administrations. As such, we control for which administration participants took part in as part our analyses of support for institutional change in Israel. A total of seventy-five students took part in the experiment. It was administered in English via an online instrument using the Otree platform.Footnote 2

We set forth the demographic characteristics of each sample in the Supplemental Appendix. We would like to make it clear here that we fully acknowledge that, due in part to the unique composition of students at Tel Aviv University, the experimental sample is not representative of larger Israeli society in terms of age, ideology, or ethnicity. Participants are disproportionately young, liberal, secular, and Jewish. This, however, does not deter from our argument that it is useful to understand the cognitive processes of individuals in the sample in terms of (1) how they think about benefits from decisions of the ISC and (2) the factors that underlie their support (and/or opposition) for proposals to change that institution at this critical juncture when its independence is under such imminent threat. Moreover, comparing those findings to what we know (and can observe about the views of US citizens via our experimental design) could be important in comparative aspects of citizens’ thinking about high courts and their outputs.

In the United States our 2023 Cooperative Elections Study module involves a larger national sample (n = 1,000). Thus, we have less concern about generalizing our findings to the population of US citizens. To be clear, however, generalization is not our primary goal in this study; we are primarily interested in understanding how the Israeli students and US citizens acting as participants in this research think about benefits from high courts and proposed change to those institutions. To accomplish that goal, various aspects of our experimental design and operationalizations are critically important. Thus, we discuss each study in some detail.

Israeli experimental design

We aim to test some of the intuitions derived from prospect theory. Our first hypothesis is that that telling people about decisions of high courts that either protect rights or constrain government actors from overstepping authority, will increase the personal and societal benefits individuals perceive as deriving from the Court compared to participants who are not told about such decisions. In testing this hypothesis in each experiment, we compare a control group that is not informed of any decision with several treatment groups that are.

All of our questions and treatments are set forth in the Supplemental Appendix to this paper. The treatment groups in the Israeli student study are manipulated in two important respects, but it is important to note that all of the treatments (1) remind participants about a specific democratic benefit the ISC provides (in upholding citizen rights or constraining government officials), and also (2) informs participants of a decision that upholds rights (or constrains government actors) in a manner that will either be consistent or inconsistent with respondents’ policy preferences. We believe this is an important aspect of our study that can help us understand the relative importance of democratic and substantive policy benefits high courts provide in a novel manner.

Our treatments involve at 3x2 experimental design. First, we vary the subject matter of the decision given to participants in each treatment group. Four of the six groups are given cases that describe decisions that uphold rights (equal treatment or free speech rights) and the other treatment groups are given a decision that strikes down government action. We expect all participants who are given these cases that expand rights or constrain action will rate benefits from the court as higher than the control group who is not told about any decision. Moreover, this aspect of the design should allow us to see if different kinds of decisions are considered more beneficial than others.

The second variable we manipulate is the litigant who benefits from the court’s judgement. To do so, we attempt to leverage the ideological, ethnic, and secular/religious divides that exist in current Israeli society. Our thinking is that peoples’ estimation of how much a case serves personal or societal interests might depend on who is on the winning side. Thus, in the case where participants are told about a constraint on government power, half of the people in the treatment are told the court ruled against a recent action by the current Netanyahu government because it failed to meet the reasonableness standard, and half are told the ruling was against the prior centrist Lapid government for the same reason.

In the equal treatment scenario, either an Israeli Arab or a secular Jew is objecting to state enforcement of Kollel rules, which guarantee religious Jews a minimum standard of living as they devote their time to religious pursuits. The court rules that doing so, without providing similar protections for others, violates equal treatment of Israeli citizens. In the free speech scenario, either secular Jews (or religious Jews) have free speech rights to protest the enforcement (or lax enforsement) of religious dietary rules upheld in public hospitals during Passover). Versions of all experimental manipulations in both national contexts are set forth in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparative Experimental Design Treatments

After the participants in each treatment group are told about the decision, we specifically ask them what they think of the decision using a six-point scale (with answers anchored at strongly support and strongly oppose).Footnote 3 We then ask all participants, including those in the control group, about (1) how much society has been influenced and (2) “people like you” have been influenced by decisions of the Supreme Court (with answers ranging from 1 to 7, anchored at “benefitted a great deal” and “been hurt a great deal”).

Finally, because we are particularly interested in how the perceptions of societal and personal benefits from the Israeli High Court influences their level of support for measures to change the institution, we then ask participants about their opinions concerning proposals to change the court. Specifically, we ask them about their level of support for (1) generic “changes” to the Court, and three more specific measures involving (2) allowing the Knesset to overrule court decisions, (3) giving the ruling coalition control over the judicial selection committee, and (4) limiting the implementation of the reasonableness standard. In the Israeli student sample these questions are on a six-point scale. Anchors indicate respondents “strongly support” or “strongly oppose” change measures.

CES experimental design

Our experiment in the United States was administered as part of a CES university module in fall of 2023. It was purposely designed to be quite similar to the experiment in the Israeli student sample. In the CES sample, one-third of participants were in the control group. Those in the control group were not told about any case before we asked them about benefits that society and people like them derived from decisions of the USSC. Our experimental treatment had a 2x2 design. Once more for participants in our treatment goups, we utilized (1) a case constraining government actors and (2) a case that protected the rights of citizens. We also manipulated the litigants benefiting from those decisions to test the effect of substantive preferences on perception of benefits.

Participants in the United States in treatments involving government constraint received a case about executive overreach where they were told about a decision where the Supreme Court struck down immigration policy implemented by either President Trump or President Biden due to separation of power concerns. We use the CES measure of 2020 vote choice as our measure of preference regarding the decision in our analyses.Footnote 4 Our other treatment case involved free speech in the context of a protest about gun rights near private corporate property. We asked all participants on the module about their support for support for gun regulations before they received case treatments as our independent measure of preferences on the policy that is the subject of speech upheld across the different treatments.

After each treatment we also asked participants in the treatment group about their perceptions of societal and personal benefits from the Court using the same six-point measure we utilized in the Israeli student sample. Finally, because we are interested in how the perception of benefits influences opinions about change to the USSC, we asked participants about their support for (1) generic “change” to the institution, as well as measures that have been discussed in the US context, (2) adding justices to the court, (3) electing rather than appointing justices, and (4) doing away with lifetime term for justices of the USSC. In the CES sample, support is measured on a seven-point scale. Unlike the Israeli sample, there is a neutral option, although answers are similarly anchored at “strongly support” and “strongly oppose.”

It is important to acknowledge that although the scenarios we employ across national contexts are similar they are not identical. First, because we were interested in looking at different types of rights high courts might confer in a society marked by significant ethnic and religious differentiation, we employ both equal treatment and free speech scenarios in Israel; we only utilize free speech rights in our CES experiment. Second, even where we are looking at similar types of decisions involving government constraint, the scenarios are different due to distinct legal standards and institutional features across our national contexts. In the Israeli sample we say the ISC stuck down action of the government because it failed to meet the reasonableness standard, while in the United States we indicate that the USSC held the President overstepped the bounds of his authority by infringing on legislative prerogatives.

Most importantly, the smaller size and relative homogeneity in our Israeli student sample compared with its CES counterpart necessitates that our analyses of the data in each experiment is not strictly identical. That said, we do our best with what we have. For instance, in both experimental samples we ask participants who are not in the control group whether they agree with the high court’s decision to which they are assigned. As such, we are able to compare the means of those who express agreement and those who express disagreement across samples. In the CES sample, we also have sufficient variance on independent measures of support for judgments (i.e., whether participants voted for or against government officials, how they feel about gun control measures) that we are able to utilize in regression analyses about perceived benefits. As noted in footnoteFootnote 3, we do not have similar independent measures of preference in the Israeli sample because of the significant homogeneity students at Tel Aviv University expressed in supporting equal treatment for plaintiffs of distinct ethnic and religious backgrounds. In discussing results, we try to be as transparent as possible about where analyses differ and the confidence we have in findings given the issues in our respective samples.

Results

Comparing perceptions of courts and benefits in Israel and the United States

We asked both samples about their perceptions of decisions of their respective high courts. A majority of student participants in the Israeli sample (55%) said they thought the ISC made decisions on a “case by case basis;” Among Israeli students who expressed bias in perceptions of the court, 39% said they thought decisions were “generally left” and only 7% said the Court leaned to the right. In the United States, 40% of participants indicated they thought the USSC made decisions on a case by case basis. Almost half of participants in the US (49%) said they thought the Court was “generally conservative” and 12% said the Court leaned in a liberal direction. Thus, participants in the US tended to see the politically appointed court in line with its current 6:3 conservative membership. Most Israeli students saw its merit selected Court as neutral, but to the extent that participants strayed from this perception, views were consistent with portrayals of the Court as a liberal leaning institution.

Israeli students and US participants both rated societal and personal benefits on a seven-point scale coded so higher number represent more benefits. Participants were asked whether they thought society and people like themselves were either much better or worse off due to decisions of their respective high courts. In general, Israeli students rated benefits from Court decisions higher than US experimental participants. The overall mean for Israeli student participants (n = 75) was 5.59 for societal benefits (closest to “somewhat better off” on the response scale) and 4.88 for personal benefits (“slightly better off”). On average, US participants (n = 999) rated societal benefits 3.74 and personal benefits 3.82 (each closest to “neutral” on the response scale). The average of total benefits for each group (societal + personal benefits ratings) was 10.47 and 7.56, respectively Tables 2.

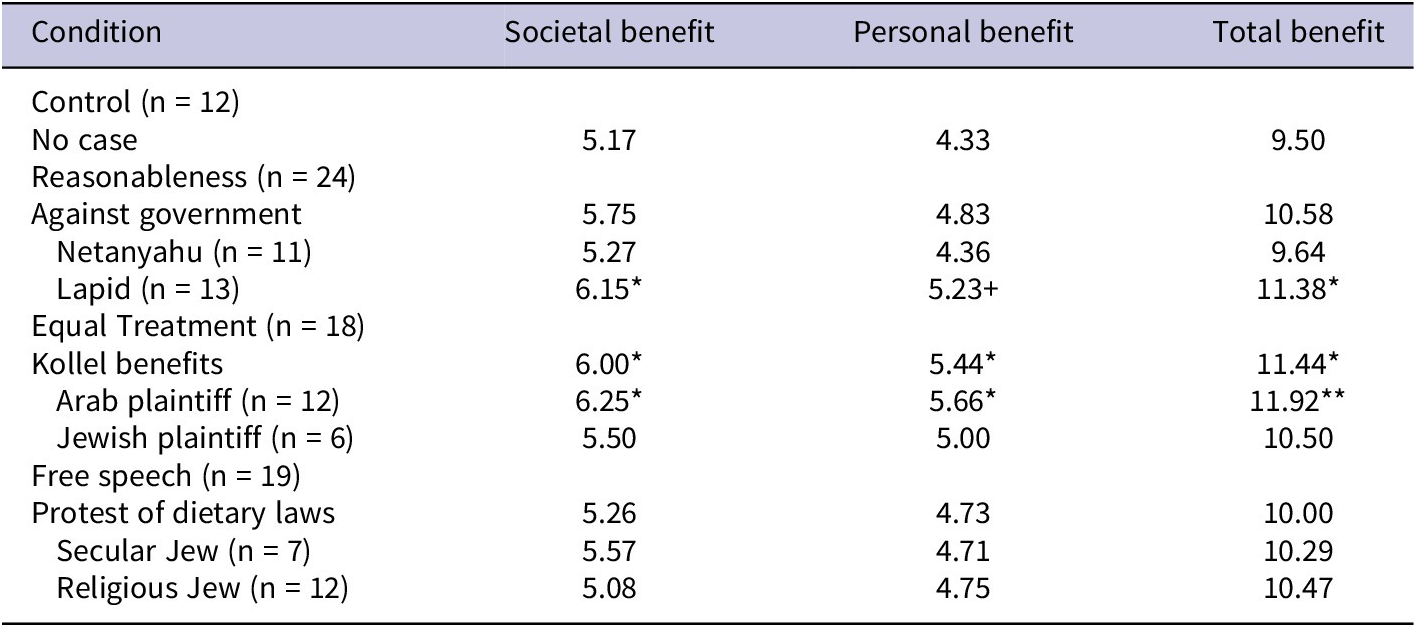

Table 2. Mean differences Across Treatments: Israeli Student Sample

Note: Indicates mean is significantly different from control at +.10, * p < .05, ** p < .01

Although Israeli students rated both types of benefits higher than US participants in our study, the correlation between the two types of benefits was lower (r = .60**) than for citizen participants in the United States (r = .73**). Interestingly, Israeli students were more likely to attribute societal benefits to decisions of the ISC than personal benefits, while participants in the United States tended to rate personal benefits slightly higher than societal benefits. As indicated in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 this same relative pattern emerged for control groups in each sample. One reason for this difference could be that Israeli society is generally more communal and less individualistic than American society given its religious tradition and history of kibbutzim.

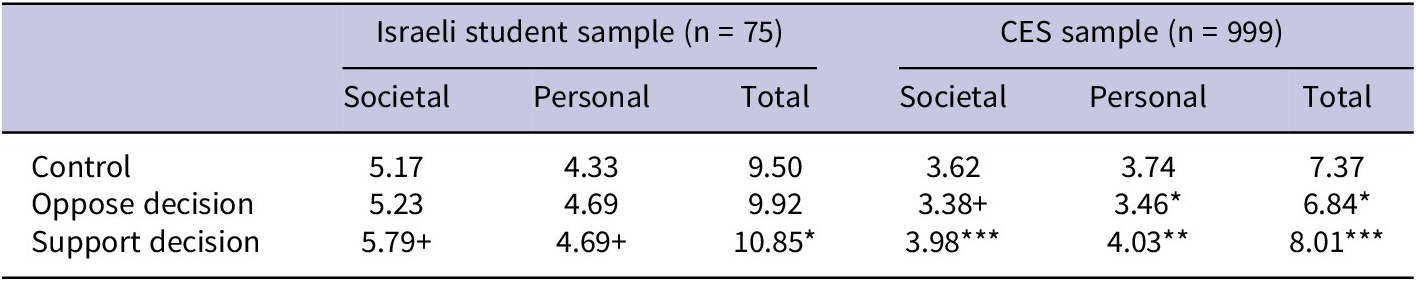

Table 3. Benefit Means Across Samples by Support for Decision

Note: Indicates mean is significantly different from control at +.10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

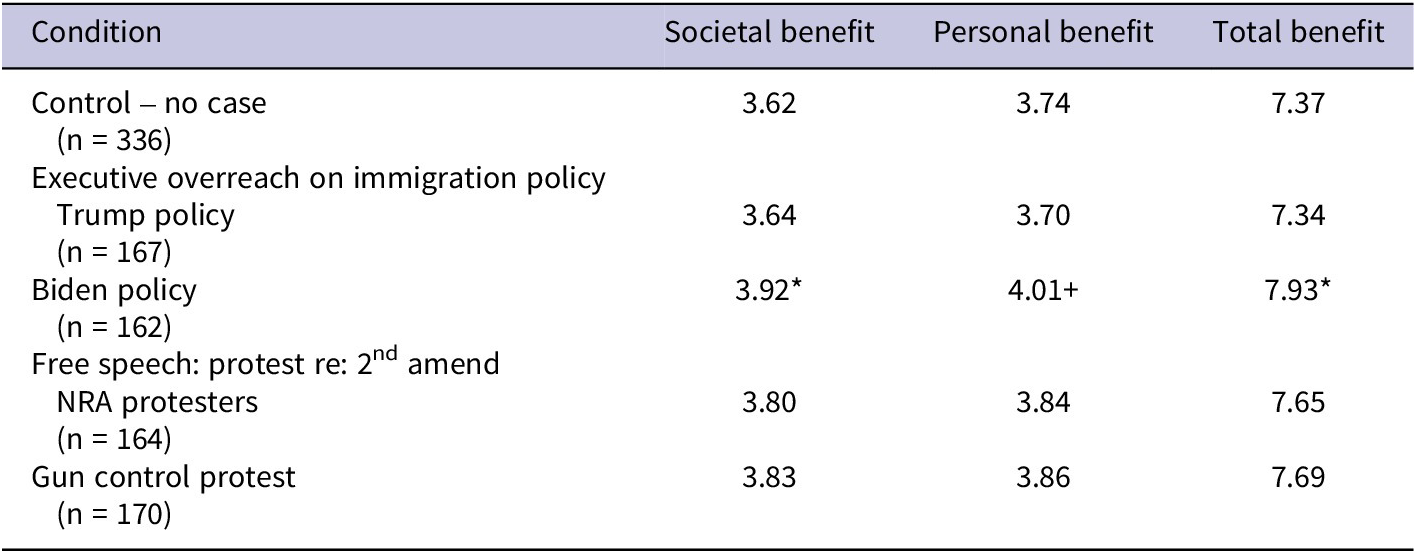

Table 4. Mean Differences Across Treatments: 2023 CES Sample

Note: Indicates mean is significantly different from control at +.10 and * p <. 05

Finally, although benefit ratings were correlated with more liberal ideology (and Democratic partisanship in the US), these correlations were quite moderate (r = .43** correlation between total benefits and ideology for Israeli student sample; r = .36**idol, .31**pid for US participants). Consistent with Braman’s (Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b) evidence, this suggests that participants’ benefit assessments are distinct from more general political orientations in both national contexts.

Considering endowment effects in Israel

Mean differences across treatment groups in the Israeli student sample appear in Table 2. It is worth noting that every group that got a treatment where they were told about a case where the High Court either constrained the government or upheld citizen rights, the mean for societal and personal benefits is higher than that of the control group. As our overall sample is 75, some of the treatment groups (particularly for equal treatment cases involving a Jewish plaintiff and free speech cases involving secular protesters) were quite small. Thus, we also aggregate cases by subject for participants who got the (1) reasonableness treatment, (2) Kollel benefits treatment, and (3) free speech treatment involving a protest about the enforcement of Passover dietary laws in public hospitals.Footnote 5

Our analysis indicates that participants who got the equal treatment cases involving Kollel benefits rated both societal and personal benefits from the Court significantly higher than those in the control group (two-tailed t-tests = 2.10 societal benefits; 2.30 personal benefits; t = 2.54 total benefits). Thus, it appears that telling students about cases that constrain government actors or protect citizen rights can increase the benefits they perceive as emanating from the Israeli High Court. These differences were significant where students were told about cases involving the protection of equal treatment for Israeli citizens involving Kollel laws, but not when they were told about cases involving free speech in the context of protests about religious dietary restrictions, or cases that made reasonableness findings against the government.

Interestingly, benefits were higher where the case was brought by an Arab Israeli plaintiff than when a nonreligious Jew was objecting to the laws. Of course, the sample size in for the treatment with the Jewish plaintiff is quite small. Moreover, this finding is likely a reflection of the significantly liberal nature of the student sample at Tel Aviv University detailed in the Supplemental Appendix. This same trait, however, makes it puzzling that hearing of a decision against the centrist Lapid government resulted in higher benefits ratings than for those who were told of a decision against the right-wing Netanyahu administration. It could be that the short-lived interim Lapid administration (July 2022–November 2022) was particularly unpopular, or that to the extent people view the court as left leaning – it is taken for granted that they will strike down actions of a right leaning administration; when they strike down an action from a centrist administration, however, it may be seen is a clear indication of wrongdoing on behalf of governmental actors, and thus more beneficial to Israeli society and its citizens.Footnote 6

Given the substantial homogeneity of views in our student sample, it is somewhat difficult to probe the role of those preferences in ratings of benefits across treatments (this is particularly true for rights-oriented decisions because of the substantial support for equal treatment among ethnic and religious groups). Recall, however, that our treatments specifically told all participants about a democratic benefit that the high court provided, and then presented them with a case that may or may not be consistent with their preferences. One thing we do observe is that participants in the in our student sample were generally less likely to say they opposed the decision of the high court. Only thirteen (or 21%) of sixty-one participants in the treatment groups expressed opposition to the decision compared to about 30% of participants the CES sample.

As set forth in Table 3, the average benefit ratings of participants who expressed opposition to the court’s rulings were higher than that of the control group, although differences were not significant. Similarly, the forty-eight (79%) students in the treatment groups who expressed support for the Court’s decision had higher ratings than the control group; differences are marginally significant for societal and personal benefits and statistically significant for total benefits. Thus, in our Israeli student sample it appears that reminding participants about a democratic benefit the High Court provides tended to boost benefits ratings, even if they disagreed with the substance of the decision that they were presented with in the treatment. Where participants agreed with the decision, the cumulative effect of the reminder about the Court’s democratic role and substantive benefit was more pronounced.

Compare this to patterns in the CES sample in the United States where the average benefits ratings for those who opposed the High Court’s decision was consistently lower than the control group’s ratings. Where participants agreed with the Courts’ decisions, benefits ratings were significantly higher than the control group’s across the board. This pattern suggests that substantive disagreement with the Court’s decision can dominate over potential benefits participants attribute to the institution from being reminded about the Court’s democratic role in society. Where participants agree with the Court’s judgment, as we observe in the Israeli student sample, the cumulative effect of the reminder about democratic goods the Court provides and the substantive benefit of the decision is substantial.

Endowment effects in the United States

The pattern above suggests we need to consider participant’s preferences seriously in probing the potential role of endowment effects in the United States. Luckily, we have a larger sample size and more variation in participants’ preferences concerning our treatment cases, allowing us to do so. Table 4 sets forth the mean differences of benefit ratings across the various treatment groups in our CES sample. Again, we observe that in three out of four instances, societal and personal interests are rated higher among participants who were told about cases than in the control group (the exception is when Trump’s immigration policy is overruled). Participants who heard about a case where the Court overturned an immigration policy put forth by President Biden, rated societal benefits significantly higher and personal benefits marginally higher than in the control group (t-test scores are 2.08 and 1.95 respectively, and 2.18 for total benefits). These group means however do not account for participants’ political preferences, and so likely mask important variation among those who agree and disagree with the cases we employed in our treatments.

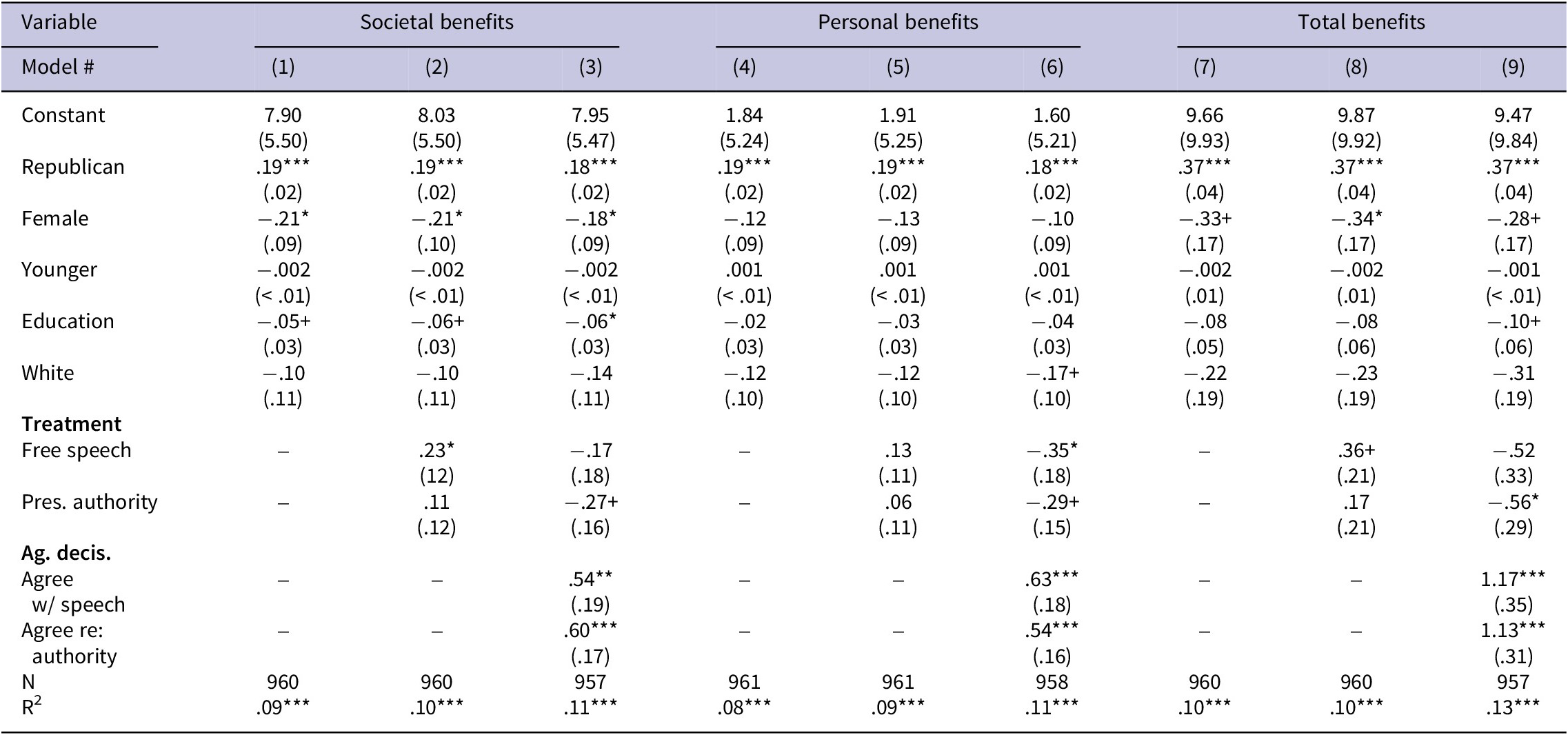

To account for such differences and observe the influence of political and demographic variables that may influence benefit assessments, we set forth a series of Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regressions in Table 5 employing our three types of benefit ratings as dependent variables. In the first set of regressions for each benefit type (models 1, 4, and 7) we control for demographic factors including partisanship (with higher numbers representing strong Republican identification), gender (coded dichotomously, 1 female/0 other), age (operationalized by birth year), education (with higher numbers representing more formal education), and race (1 white/0 nonwhite). In the second set of regressions (2, 5, and 8), for each benefit type we include dichotomous variables representing whether participants were given the Free Speech Protest or Executive Overreach case; the control group is our excluded reference category.

Table 5. OLS Regression of Benefit Ratings: CES Sample

Note: Indicates significance at + p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 (two-tailed)

The third set of regressions for each benefit category (models 3, 6, and 9) include a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not the participant expressed agreement with the type of plaintiff whose rights were upheld for those who were given the Free Speech treatment (1 agree/0 otherwise). For participants in the Presidential Overreach treatment, we coded agreement as 1 if they did not vote in the 2020 election for the relevant president (Trump or Biden) who had their immigration policy overturned in the treatment to which they were assigned.

Results demonstrate that Republicans tend to perceive more societal and personal benefits from decisions of the Court. This is likely a result of the Court’s current conservative makeup. On average females tend to perceive significantly fewer societal and total benefits from Court decisions. Given the Court’s 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization overturning the federal right to abortion announced in Roe v. Wade (1973), it is not too surprising females see fewer benefits emanating from the Court in the current political climate. Other coefficients indicate that, on average, non-Whites perceive more benefits than those who identify as White, and younger individuals tend to attribute more personal benefits but fewer societal benefits than older individuals from decisions of the Court, but these differences are not significant. Somewhat surprisingly, the regression reveals those who are less educated attribute more societal benefits to the Court’s judgments than more educated citizens in our sample.

The models that include the treatment dummies (2, 5, and 8) indicate that participants who were informed of case decisions protecting rights or constraining executive authority tended to rate benefits higher than those in the excluded control group. This difference was only significant, however, for societal benefits ratings of participants in the Free Speech treatment groups.

Taking policy agreement into account (in models 3, 6, and 9) shows that those who agreed with the decision to which they were assigned were significantly more likely to rate benefits higher. Those who did not agree with those decisions had significantly lower personal benefits ratings where they were given the Free Speech treatment, and marginally lower societal and personal benefits ratings in the Presidential Overreach conditions, as reflected by the coefficients for those variables. Moreover, the size of the coefficients for participants who agree with the decision is substantially larger than for participants who disagree. This may be due to the effect of our compound treatment where participants are reminded about the Court’s democratic role, accompanied by a decision with which they agree. The lower values for those who disagree may reflect the fact that the information about the Court’s democratic role is at odds with participants’ substantive policy views in those instances.

At any rate, it seems clear that informing citizen participants of Supreme Court decisions that protect free speech rights or constrain government actors was not sufficient to increase perceived benefits from that institution without considering whether those decisions were consistent with their political preferences. Where such decisions were consistent with participants’ views, it significantly added to their assessments of benefits from the institution, but where decisions were inconsistent with their priors, hearing about Supreme Court cases tended to detract from benefits judgments. Overall, this evidence suggests that substantive policy considerations are more important than the democratic role the Court plays in our system of government in participants’ assessment of benefits from the institution.

Do perceived benefits influence support for institutional change to high courts?

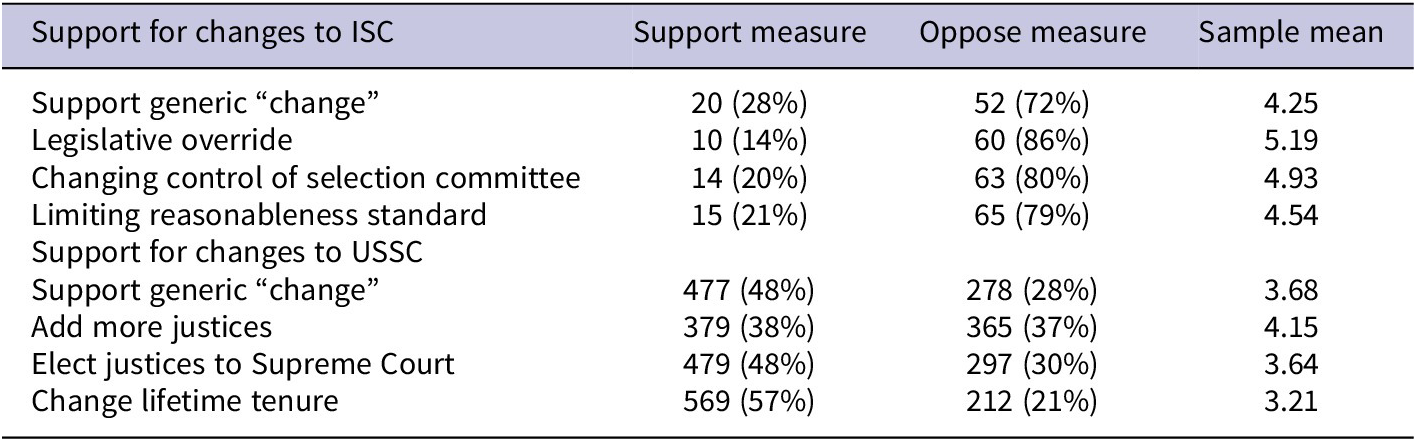

We now turn to the question of whether perceived benefits influence support for change to high courts across our samples. Table 6 sets forth support for changes that we asked about after prompting participants to think about benefits from their respective high courts. Israeli students were asked about their opposition to measures on a six-point scale. The CES module employed a seven-point scale with a neutral option. Higher scores on the scales represent more opposition to each proposed measure. Obviously, these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt because we cannot know if they would have been different absent our experimental treatments, but generally they demonstrate a good deal of opposition to changes to the ISC among participants in our student sample, and more support for change to the USSC in the CES sample.

Table 6. Support for High Court Reform in Israeli Student and CES Samples

Given the high levels of opposition to change among our Israeli student sample, it is important to reiterate that we are not arguing here that this is a representative sample of the Israeli population. Student participants are disproportionately young, liberal, Jewish, and secular. Moreover, they live in a region of the country where protests against the proposed reforms have been quite prominent over the last two years. Opponents of such measures have consistently portrayed the proposed changes to the Court as an attempt by political leaders to consolidate their authority at the expense of judicial independence. Indeed, one respect in which our sample mirrors the larger population is that they seem most troubled by what is arguably the biggest threat to that independence, allowing a majority of the Knesset to override decisions of the ISC.

The question we are concerned with is: what underlies this opposition? Is it politically determined in this polarized environment or do the benefits individuals perceive as emanating from the institution play a role in citizens’ thinking? Braman (Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b) showed that perceptions of past benefits and future expectations about Court decisions influenced citizens’ support for proposals to change the USSC at the height of the 2020 presidential primary season. Controlling for general political orientations, those who expected future benefits from decisions of the Court were particularly likely to oppose changes that could put those benefits at risk. But threats to the Court in the United States were never as imminent as they have been in Israel. Moreover, proposals to change the USSC have come from both sides of the political aisle over last twenty years (Zezima Reference Zezima2015; Phillips Reference Phillips2020). Perhaps most critically, the United States has a much longer history of judicial review; this suggests citizens in the United States might have a stronger “sense of psychological ownership” in benefits from judicial review. Indeed, evidence above tends to demonstrate US citizens and Israelis think about benefits from high courts quite differently, with Americans more likely to perceive more personal than societal benefits emanating from their outputs.

All this is to say, it is not obvious that the same factors that have been demonstrated to influence Americans’ thinking about changes to its Supreme Court will necessarily operate in the same way in the minds of Israelis due to distinctive aspects of the national and political context. Given that our study was designed to get at this very question, it is to this matter that we turn now.

Determinants of support for changes to the USSC

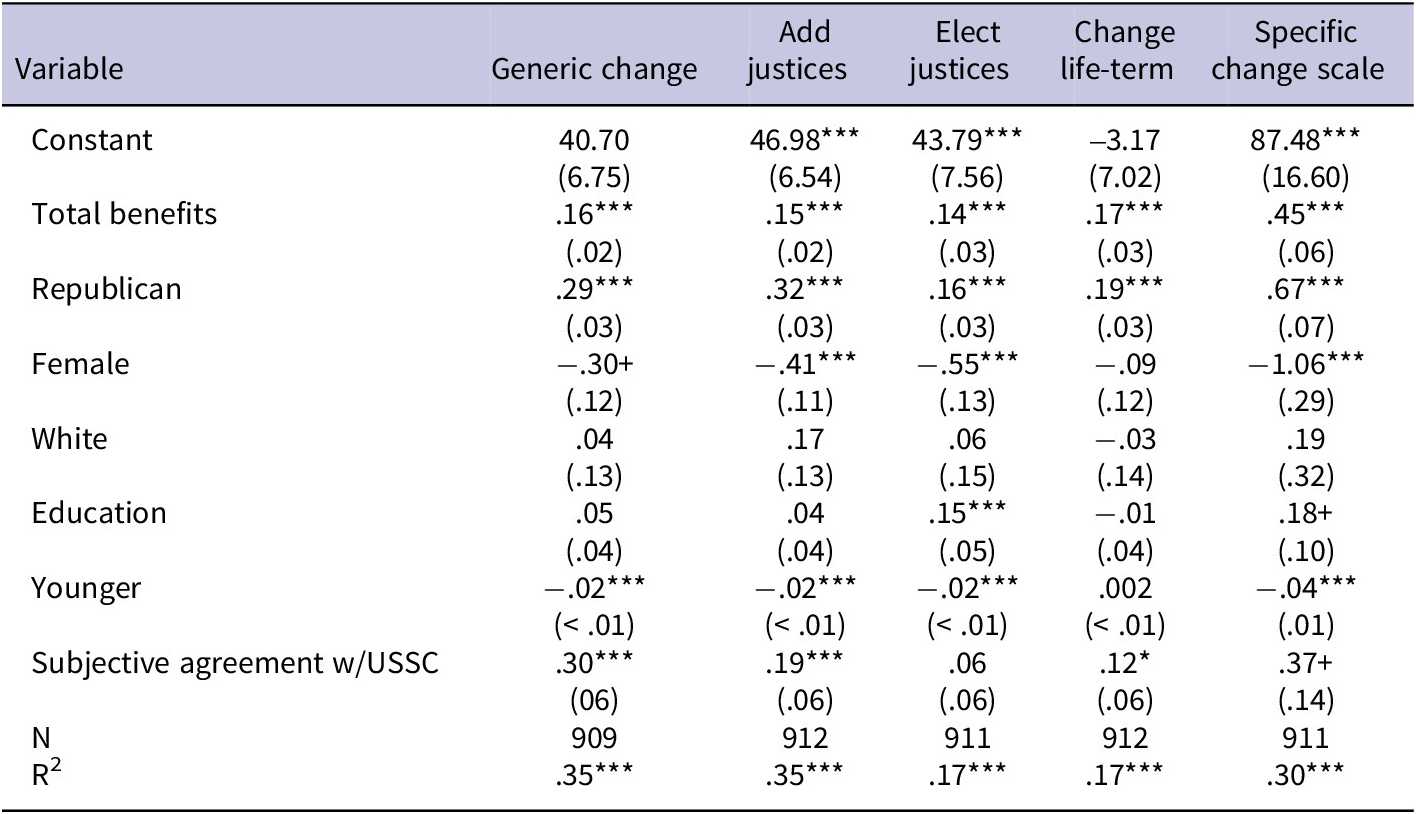

We start by exploring variables underlying support for change in the United States by employing an OLS regression on our various measures of the concept. We then explore determinants of support for change to the Israeli High Court in the Israeli student sample. Specifically, we conduct five separate OLS regressions on (1) our generic question about support for “change” to the Court, (2) each of the three specific institutional changes we asked about ((a) adding justices to the court, (b) electing Supreme Court justices, and (c) changing life terms for justices), and (3) finally, an additive scale of the three specific change measures. Higher values for each measure indicate more opposition.

Our primary independent variable of interest is participants’ assessment of total benefits from decisions of the Supreme Court (societal benefits + personal benefits). Note that here we employ current benefit assessments rather than employing past or future benefit assessments confined by a specific time frame as has been the case in prior studies (Braman Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b). Recall our hypothesis is that consistent with intuitions from prospect theory, those who perceive greater benefits should be in the domain of gains and thus more likely to oppose changes to the institution.

We control for political and demographic factors using the same variables described above. We also control for subjective agreement with the Court’s decision-making, employing Bartels and Johnston’s (Reference Bartels and Johnston2013) four point measure. Our expectation is that Republicans should be more opposed to changes because Democratic candidates and politicians have been the ones championing proposals to change the Court since the 2020 primary season. Consistent with Braman (Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b), we expect females and younger individuals to be more supportive of institutional changes; more educated individuals should be more opposed to changes (presumably because they have proprietary knowledge about how the current system operates, and thus some advantage in maintaining the status quo). Those who agree with the Court should be more opposed to implementing proposed changes.

Table 7 sets forth results of our analyses. Consistent with Braman (Reference Eileen2023a, Reference Braman2023b) and intuitions from prospect theory, those who perceive more current benefits from decisions of the court are significantly more likely to oppose changes to that institution, controlling for relevant political and democratic factors. This is true for the generic change scale, each of the individual measures we asked about, and the scale of specific proposed changes to the Court. We also see that Republicans are more likely to significantly oppose all change measures. Subjective agreement with the Court tends to increase opposition to change, but its significance varies across different kinds of proposed changes. Younger individuals and females tend to be more supportive of changes than older individuals and those who do not identify as female, though these differences are not significant for changing term limits, the specific measure that garnered the most support in our sample. Those who are more educated tend to oppose electing rather than appointing Supreme Court justices significantly more than those who have less formal education.

Table 7. OLS Regressions CES 2023: Opposition to Changes to the USSC

Note: Indicates significance at + p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 (two-tailed)

In terms of substantive significance, the effect of perceived benefits is powerful. For instance, the coefficient for partisanship and total benefits are .19 and .17 in the model of opposition to changing term limits for Supreme Court justices, respectively. As we go from 1 (strong Democrat) to 7 (strong Republican), opposition increases by 1.14 points on the seven-point scale, or by 17%. As we go from the minimum of 2 to the maximum of 14 on the fourteen-point total benefit measure, opposition increases by 2.21 points, or 16%. Thus, the desire to maintain the status quo where one believes the Court is providing personal and societal benefits can be important in shaping opposition to proposed changes to that institution.

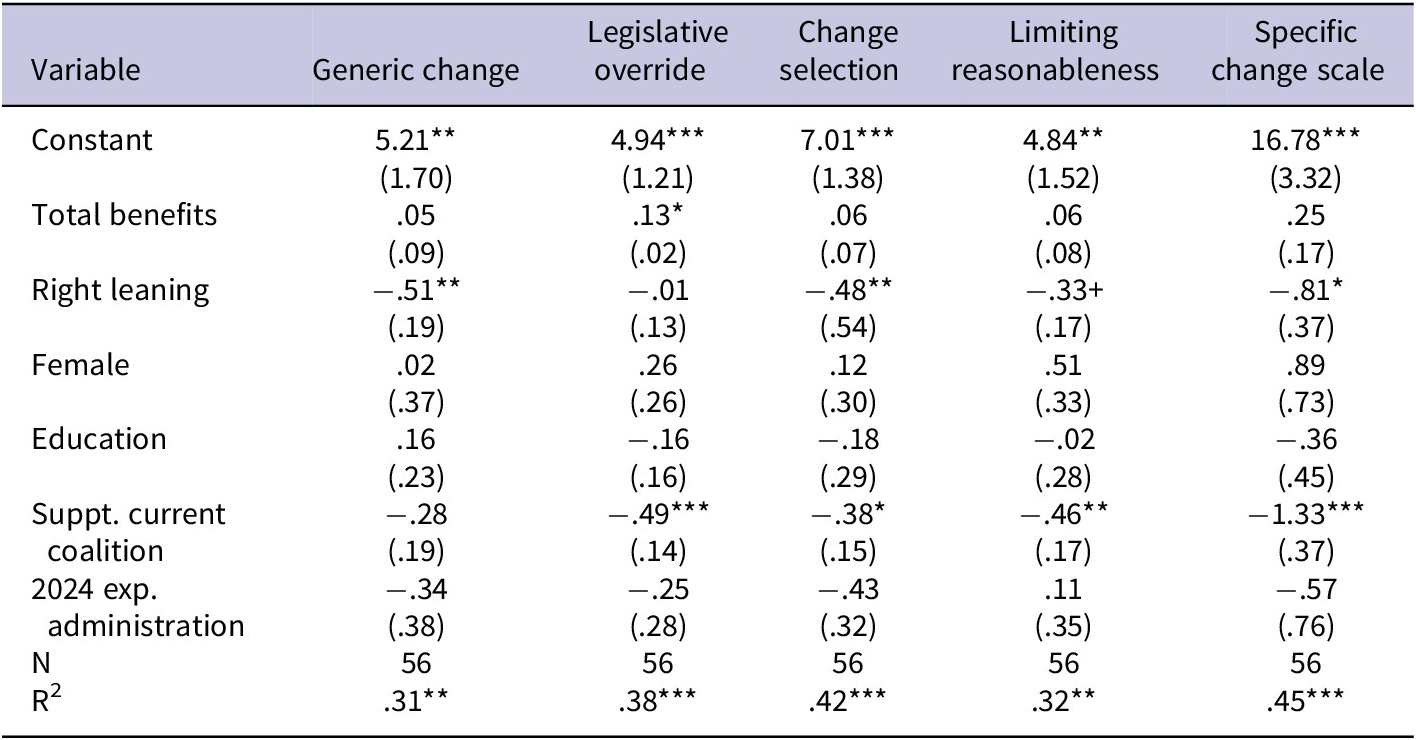

Determinants of support for changes to the ISC

Before discussing our OLS analyses of support for change in the student sample in Israel, a couple of important caveats are in place. First, as acknowledged previously, the sample is pretty homogenous – this means we do not have a lot of variation on some of the variables (like age, education) that may be important in the general population in determining support for fundamental institutional change. As such, we would like to emphasize that our findings only apply to the students in our analyses. Second, (as referenced in the Supplemental Appendix) there was a good deal of attrition in answering questions in the survey among our student participants. A total of nineteen students failed to answer any of the demographic questions we asked of them (including gender); that number increases for more sensitive questions like age. As such, our total N for the multivariate analyses is, admittedly, quite low (fifty-six students across all measures).

Still, we undertake the task because discovering what is relevant in the opinions of students at Tel Aviv University during this era of substantial threat to the independence of the ISC is not nothing. Contrary to popular opinion, university students are, in fact, people. Knowing how they think about this important issue may give us insights into the views of other Israeli citizens as long as we are careful to acknowledge how they are different and, most critically, how those differences may cause them to think about changes to the ISC in a manner that is distinct from others in society.

In conducting our analyses, we use the same total benefits measure detailed above. Our dependent variables are the (1) the six-point generic change question, (2) each of the specific measures we asked about ((a) providing for a legislative override of Court decisions, (b) changing control over the selection committee, and (c) doing away with the reasonableness standard that the Court uses to strike down government action), and (3) the additive scale of opposition to specific change measures. Questions about specific measures were all asked on a six-point scale, with higher numbers representing more opposition.

We control for (1) ideology (five-point scale with higher numbers representing more right leaning orientation), (2) gender (1 female/0 other), (3) education (with higher numbers indicating participants with more formal education), (4) participants level of support for the current government (coded 1 to 5 with higher numbers indicating more support), and (5) whether they took part in the study in the Summer 2023 or the Spring 2024 experimental administration (1 for 2024/0 otherwise).

Results of the OLS analyses appear in Table 8. We see in the Israeli student sample political considerations tend to predominate in thinking about institutional change.The total benefits variable is consistently in the expected direction, indicating that those who perceive more benefits from the ISC tend to be more opposed to proposed measures changing that institution, but the variable is only significant in the analysis of opposition to the legislative override. Students who expressed right of center ideology and those who support the current coalition government are both more likely to support changes to the Israeli High Court.Footnote 7 Rightwing ideology is significant in three of the five analyses and marginally significant for limiting the reasonableness standard. Support for the coalition government is significant in four of the five regressions, only failing to achieve significance on the generic change measure.

Table 8. OLS Regressions: Opposition to Changes to ISC

Note: Indicates significance at + p < .10, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001 (two-tailed)

Thus, although the Israeli students in our study rated benefits from their high court higher, on average, than citizens in our United States sample, those benefits were less impactful than political factors in their opinions about change to that institution. We turn to why this might be, along with a general discussion of the rest of our results in the concluding section.

Discussion and conclusions

The inquiry yielded interesting findings about how participants viewed benefits from high courts in both Israel and the United States. First, we observed that consistent with intuitions about endowment effects from behavioral economics, informing participants about decisions from high courts had an observable influence on participants’ perception of benefits from those institutions. This could have implications for how individuals in both nations process, store, and recall information about courts. Of course, we cannot say from this study how long such effects last. We also cannot say whether, as some scholars have theorized (Gibson Reference Gibson2024), they leave an impression in some online evaluation in people’s minds, or whether feelings about particular cases come to mind in a more random manner when individuals are asked about their opinions of courts in line with memory-based models of evaluation (Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). Still, this seems like a solid a step forward in in understanding the relationship between citizens’ evaluation of high courts and their outputs.

Second, of the cases we explored, the equal protection case had the strongest influence on benefits perceptions in Israel. Admittedly, this particular finding might reflect the strength of our manipulations, or it may be an artifact of this particular sample where participants seemed quite supportive of equal protection, in general. In the United States, telling participants about a case that conferred free speech rights and one that constrained the government worked similarly in shaping participants’ perceptions of benefits from the USSC.

It is worth noting that Israeli participants tended to report more societal than personal benefits emanating from the outputs of the ISC. The opposite result obtained among individuals in the United States who took part in our study, and the relationship between the two types of benefits, was tighter, as reflected by the higher correlation between the two. This particular pattern could indicate that, even though participants in the Israeli student sample rated both type of benefits higher on average, Americans have internalized those benefits to a deeper extent; benefits from the Court are more likely to be acknowledged as influencing the fortunes of people like respondents themselves than society at large. This could be the case due to America’s constitutional tradition or its longer history of judicial review.

It appears, however, that there may also be a downside to longer experience. Americans rated benefits lower on average than Israeli participants in this study. Moreover, participants in Israel who heard of cases that constrained government or protected rights were more likely to perceive the Court as providing benefits than those who did not get our treatment, even when they disagreed with the substantive outcome of the decision itself. In the United States, participants’ policy views about cases were clearly more important in the perception of democratic benefits from the USSC. This could suggest United States citizens are so used to the Supreme Court as a partisan player in their democracy, that they tend to see the court like other political institutions. One cold argue this finding demonstrates that US citizens now take the special role the Court plays -- protecting rights and keeping government officials in line -- for granted. Alternatively, it could reflect just how politicized the institution has become. At any rate, findings here tend to add to the growing body of research suggesting substantive policy views can override citizens’ feelings about democratic functions that the Court performs in the United States. The contrasting findings in Israel reminds us, however, this is not inevitably the case.

Finally, American’s feelings about benefits from the decisions of the Supreme Court were important in shaping support for and opposition to change to that institution controlling for other relevant factors. Consistent with intuitions from prospect theory, those who saw more personal and societal benefits emanating from the Court were more resistant to proposals to change it. Although coefficients in our Israeli student sample trended in the right direction, for the most part they were not significant.

Of course, it is possible that if we had a larger sample with more variation on relevant variables, we would have seen a stronger effect. But it is also possible feelings about benefits from judicial institutions do not play the role in Israel that we observe in the United States for other reasons. The extreme context in which proposals to change the ISC arose might cause political attitudes to predominate in determining support for those measures. Alternatively, consistent with recent findings in behavioral economics, there could be substantial differences in Israeli citizens’ “psychological sense of ownership” concerning high court outputs, where they have a relatively shorter history of judicial review. To be clear, we cannot tell if one or some combination of these factors drives this observed difference in our findings. We leave it as a potential avenue for future research, hoping that this inquiry demonstrates the usefulness of exploring how citizens think about high courts in different national contexts.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2024.32.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ted Carmines, Chris Krewson, Rich Pacelle, The Center for the Study of American Politics at Indiana University, participants at the 2024 Annual Conference of the American Political Science Association, 2024 Political Science Colloquium series at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the Editor and anonymous reviewers at the journal of Law and Courts for their extremely helpful comments on this research.

Data availability statement

Replication Materials are available on the Journal of Law and Court’s Dataverse Achieve.