1. Introduction

Democracy has long been regarded as the most preferred system of government; however, recent research suggests a global decline in support and commitment to it (Carlson and Turner, Reference Carlson and Turner2009; Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2016, Reference Foa and Mounk2017; Shin and Wells, Reference Shin and Wells2005; Chu et al., Reference Chu, Huang, Lagos and Mattes2020; Simonovits, McCoy, and Littvay, Reference Simonovits, McCoy and Littvay2022). Scholars have attributed this decline to various factors, including economic concerns, disconnected elites (Wike, Silver, and Castillo, Reference Wike, Silver and Castillo2019), rising populism (Sinkkonen, Reference Sinkkonen2021), foreign pressure (Hellmeier, Reference Hellmeier2021), state dependency (Rosenfeld, Reference Rosenfeld2020), and individual sentiments, such as self-uncertainty (Hogg, Reference Hogg2021). These factors have contributed to a ‘renewed pessimism’ regarding democracy, leading to a ‘deepening global [democratic] recession’ (Croissant and Haynes, Reference Croissant and Haynes2021; Lewsey, Reference Lewsey2020). This declining support is particularly concerning since sustained and widespread public support is crucial for democracy’s survival and effectiveness (Easton, Reference Easton1968, Reference Easton1975; Lipset, Reference Lipset1959; Dalton, Reference Dalton2013; Claassen, Reference Claassen2020; Shin, Reference Shin2011).

Surprisingly, this democratic withdrawal is increasingly evident among the youth (Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2017, Reference Foa and Mounk2019). Historically, the young demographic has been at the forefront of democratic movements and has played a critical role in the evolution of democratic politics, as their support enhances regime legitimacy over time (Norris, Reference Norris1999; Dalton and Welzel, Reference Dalton and Welzel2014). However, they are now growing disillusioned with liberal democratic institutions and are ‘deeply disappointed with existing democratic institutions’ (Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2019, 1014), ultimately leading to a ‘democratic disconnect’ (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Wenger, Rand and Slade2020).

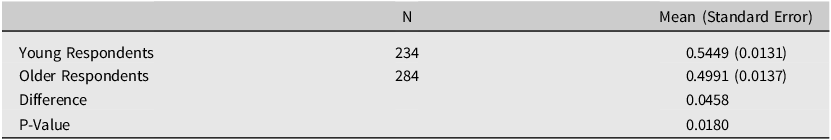

Similarly, data from the World Values Survey, which has been conducted over five waves from 1995 to 2022, reveal a decline in support for democracy in South Korea. Table 1 shows that, while support has steadily declined across all age cohorts, with an average decrease of 13.6 per cent from 1995 to 2022, the decline is particularly pronounced among young individuals. The youngest cohort experienced a 12 per cent decrease, while the second youngest cohort saw a 13.2 per cent decrease in support from 1996 to 2022.

Table 1. Attitudinal change in democratic system preferences by age, cohort, and time

This indicates that young individuals are becoming more apathetic towards democracy and also more receptive to other regime alternatives (Berthin, Reference Berthin2023; Mauk, Reference Mauk2020). In particular, there is a rapidly growing trend of support for strongman, authoritarian leadership due to their seemingly assertive and charismatic leadership, appeal to identity politics, excessive nationalism (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022), and ‘hypermasculine and hubristic performance’ (Higgott and Reid, Reference Higgott and Reid2023). These strongman leaders may be particularly appealing due to their alleged reliability and their promises to address challenging situations. Additionally, they give off the impression that they will handle issues quickly and swiftly. As a result, this appeal may be particularly strong among young citizens grappling with growing fear and vulnerabilities by offering a sense of security and stability, even within democracies (Foa, Reference Foa2021).

In this way, the emergence of support for strongman politics seems to coincide with the global trend of democratic backsliding, where strongman leaders have gained power and momentum in new ways and in very different environments (Ruud, Reference Ruud2023). While strongman leadership and democracy have historically represented two distinct paradigms of governance that stand in stark contrast to one another, now the former is no longer confined just to authoritarian systems. Strongman leaders have made it increasingly difficult to differentiate between authoritarian and democratic forms of leadership, as they ‘maintain a veneer of democracy while stealthily furthering their own agendas’ (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022). The changing and adaptable nature of these leaders, along with increasing discontent with democratic institutions among young individuals, is now putting consolidated democracies like South Korea under immense strain, essentially posing as one of the greatest risks to liberal democracy worldwide (Kim, Reference Kim2023).

In many ways, support for democracy does not seem to differ significantly across age groups in South Korea (hereafter Korea), which indicates that democracy overall continues to be favoured as a form of government across all cohorts. This may especially be the case since the concept of ‘democracy’ has a positive connotation and often carries a brand name (Linz and Stepan, Reference Linz and Stepan1996), particularly in the case of Korea due to a long history of democratic movements among ordinary citizens (Koo, Reference Koo2002). However, when unpacking different democratic traits, there may be some variation in terms of support (Shin and Kim, Reference Shin and Kim2017, Reference Shin and Kim2018). In particular, there seem to be significant age differences in support for the non-democratic trait of strongman leadership in the Korean context. This contrasts significantly with other countries, where both declining support for democracy and increasing support for strongman leadership coincide by age group.

As such, this study examines whether Koreans, specifically young Koreans, are more likely to support democratic government forms than autocratic ones. It poses the following questions: Are Korean citizens more likely to support democratic political leadership compared to strongman, autocratic political leadership? Additionally, to what extent, if at all, do young Koreans support strongman political leadership compared to older generations, and why?

This study argues that while overall support for democracy may be high among the general Korean public, generational differences exist. Specifically, this study contends that young Korean individuals, historically central to democratisation movements, are increasingly expressing support for strongman, authoritarian leaders, partly due to declining faith in democracy. Additionally, strongman leaders exploit public anxieties and discontent with democracy and democratic procedures by addressing the economic insecurities and grievances of young individuals who now feel marginalised. Consequently, young Koreans find strongman leaders and their charismatic image more appealing than older Koreans, even those who may harbour autocratic sentiments due to authoritarian nostalgia. This increasing support for illiberal strongman leadership among young Koreans seriously threatens the country’s democratic future and may reflect similar challenges faced by other liberal democracies worldwide.

Based on an original survey conducted in May 2022, the descriptive statistics and results of an embedded experiment indicate that, in general, Korean citizens express greater support for democratic leadership over strongman leadership. However, young Koreans demonstrate a higher inclination towards authoritarian strongman leaders and reduced support for democratic leaders compared to older individuals. These findings empirically challenge the long-held view about young Koreans’ supposed preference for democracy, suggesting that changing values play a central role in eroding their faith in democratic leadership and institutions. Thus, this study contributes to the existing literature by prompting a reconsideration of how the changing values of the young generation may influence Korea’s democratic landscape in the future.

There has been limited empirical research on generational attitudes towards strongman leadership in South Korea. This study seeks to fill this research gap and contribute to the existing scholarship in several ways. First, while declining public support for democracy has been extensively studied, there has been limited focus on how young individuals view specific aspects of democracy, such as democratic political leadership. Second, this study examines the attitudes of youth in South Korea, a country where young individuals have historically and prominently been at the forefront of the democratisation process. Third, it incorporates an original survey and embedded experiment to examine differences in support for democratic and strongman leadership as well as generational variations in this support.

The study is structured as follows. The following section examines increasing support for strongman leadership in the 21st century, the appeal of strongman leaders across different age groups, and why young Koreans may be more likely to support strongman leaders over democratic leaders compared to older individuals. The third section describes the data and methods, while the fourth section presents the descriptive and regression results. The final section discusses the results and concludes with the study’s implications.

2. Support for strongman leadership

2.1. Defining strongman leadership

The definition of a strongman leader is subject to multiple interpretations. In general, the term ‘strongman leader’ has been loosely used to refer to those with populist authoritarian tendencies, though it can also connote dictators and those who serve unlimited terms (Ruud, Reference Ruud2023;). They readily flout rules, disregard checks and balances, and show little to no hesitation in resorting to violence (Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2024). Strongman leadership is thus a type of authoritarian political leadership, characterised by authoritarian rule (Lai and Slater, Reference Lai and Slater2006) that seeks to exert complete control over a country’s political system.

Despite its broad definition, strongman leadership has become a global trend in the 21st century, fundamentally altering global politics (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022). Many government leaders exemplify this type of leadership, contributing to its growing prevalence. Indeed, while this type of leadership used to be seen solely in non-democratic countries, now strongman leaders are appearing rapidly in democracies as well. While Putin has been described as ‘the archetype and the model for the current generation of strongman leaders’ (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022), there are other prominent ones as well. This includes Viktor Orbán in Hungary, who rose to prominent in 2010 as a strongman with charismatic authority and an icon of ‘Hungarian-ness’ (Sonnevend and Kövesdi, Reference Sonnevend and Kövesdi2024); Xi Jinping’s strongman rule in China, particularly in his early years in office from 2012 (Baranovitch, Reference Baranovitch2021); Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey in 2014, where he consolidated support in his non-traditional ways during a time of economic crisis (Schafer, Reference Schafer2021); Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines in 2016, where he maintained a tough-guy image and promised an anti-drug campaign (Teehankee and Thompson, Reference Teehankee and Thompson2016); Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil in 2018, when he appealed to voters who were frustrated with traditional government policies and diplomatic order (Trinkunas, Reference Trinkunas2018); and Donald Trump in the United States in 2016, and also in 2025, through unorthodox rule and desire for revenge (Feldstein, Reference Feldstein2024; Rachman, Reference Rachman2024).

The increasing number of strongman leaders worldwide indicates that not only are they becoming legitimised, but they are also changing the way in which they appeal to the public to maintain their legitimacy. Indeed, this trend throughout the past decade indicates the rise of a new generation of strongman leaders in both non-democratic and democratic countries, consisting of a group that is poised to significantly influence the international landscape by participating in major global decisions. This becomes especially problematic since strongman leaders can operate within democratic means by following term limits and adhering to democratic norms while simultaneously projecting decisive and assertive leadership; but at the same time, they can also choose to disregard democratic procedures and consolidate power indefinitely. In this way, strongman leaders can now choose between acting both democratically and undemocratically, and as a result, what constitutes a strongman leader can no longer be limited to certain regime types.

2.1.1. Strongman leadership characteristics and appeals

This type of strongman leadership often displays narcissistic traits, hypermasculinity, and hubris (Higgott and Reid, Reference Higgott and Reid2023). These leaders often combine authoritarianism with a personality cult, building their following among those who feel disenfranchised, marginalised, and left behind in various forms of development, including cultural, economic, and political (Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2024). They also foster solidarity by employing divisive strategies, creating collective identities among those who share similar sentiments while targeting and demonising ‘other’ enemy groups using divisive strategies (Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2024). Strongman leaders ‘have no hesitation in using violence and the threat of violence in their quest for power … They represent a resurgence of authoritarian, anti-democratic rule often in the thin guise of democracy’ (Gabriel, Reference Gabriel2024).

Scholars have identified various reasons for the rise and appeal of strongman leadership. These include their appeal to excessive nationalism, leading to an increasing number of ‘nostalgic nationalists’ (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022), as well as their appeal to identity politics, cultivation of a tough image, and focus on polarisation. Others suggest this support stems from a romanticisation of an authoritarian past, where positive aspects of authoritarian history are selectively emphasised (Kim-Leffingwell, Reference Kim-Leffingwell2023; Lee, Reference Lee2024). Some argue that it is due to the strategic use of social media to mobilise support (Ruud, Reference Ruud2023) or the way strongman leaders portray themselves as reliable figures promising to change the system, often offering short-term solutions to various issues. They share many traits, notably their ability to portray a hardline approach as a means to deliver situations during crises. As a result, they are able to build a following among the masses, particularly among disenfranchised and marginalised segments of society.

2.2. Intergenerational disparities in strongman leadership support: political and economic factors

South Korea democratised during the third wave, and the country continues to be considered one of the few fully consolidated democracies in the region, along with Japan and Taiwan. It was also one of the few countries in the region that democratised through the strength of people power movements, and in particular, with the intense, consistent, and strong political activities among young students throughout the country. Yet support for strongman leaders is now emerging even in democracies like Korea, and there is increasing support for strongman leaders among the general public. Moreover, this support seems to span across different generations.

Some studies suggest that older citizens in Korea may support strongman leaders due to a strong sense of authoritarian nostalgia, wherein they romanticise past authoritarian leaders and selectively emphasise positive characteristics related to their experiences during that regime (Kim-Leffingwell, Reference Kim-Leffingwell2023). On the other hand, strongman leaders can be appealing to young individuals as well, as they may find strongman leaders appealing through both economic and political factors

2.2.1. Intergenerational disparities towards strongman leadership: the political factor

From the political perspective, the dictatorship under Park Chung-hee is often used as a prime example for political grievances among older Koreans, since the former dictator is often associated with severe human rights abuses. In general, the current older generation was mostly children during the Park dictatorship and, as such, may be likely to maintain negative memories regarding his rule. In this way, the older generation may be reminiscent of political socialisation (see Easton, Reference Easton1968) in their experiences under Park’s dictatorship. Indeed, many older voters in their fifties and sixties remember being opposed to Park’s heavy-handed measures during that era, and they continue to be haunted by the difficult events they experienced during the dictatorial era. The dictatorship also consisted of the torture, death, and repression of young individuals, many of whom consist of the older generation living in Korea today. As a result, older voters may be less likely to harbour a sentimental desire or longing for the authoritarian past.

Conversely, they may instead show ongoing appreciation for the rise and consolidation of democracy within the country and attempt to avoid or even become hostile towards changes that seemingly have authoritarian tendencies, such as the rise of strongman leaders who resemble dictators like Park Chung-hee. Without a leader who adheres to checks and balances, it is possible that another strongman leader with similar characteristics may appear.

Among younger Koreans, however, the political perspective towards strongman leadership indicates that there have been dramatic transitions in their political stances. Young Koreans, who grew up in a vibrant democratic environment, have played critical roles that pushed the country towards democratisation. Historically, they have been at the forefront of democratic movements such as the 1980 Gwangju uprising and the 1987 June democracy protests, with students actively playing prominent roles in the movements (Lee, Reference Lee1993; Chang, Reference Chang2015). Yet with the rise of support for strongman leaders among young people worldwide in the 21st century, young Koreans are also increasingly showing more support for strongman leaders. For example, Trump appealed to many far-right young Koreans, particularly far-right young men, when he became the president of the United States in 2016 due to his display of hostility towards feminism (Yim, Reference Yim2022; Hu, Reference Hu2017). Similarly, the 2022 South Korean presidential election further marked a turning point due to increasingly growing divisions based on key issues, where young voters started to voice their discontent based on feelings of isolation within the political sphere (Jung, Reference Jung2024; Kim and Lee, Reference Kim and Lee2022).

The recent political climate has decreased the legitimacy of political leaders among young individuals, causing them to divert to alternative types of leadership. This became particularly visible as support for Lee Jun-seok, the former chairman of the People Power Party and the current leader of the Reformist Party, grew particularly among young men with increasing discontent within society (Lee, Reference Lee2024; Jenkins and Kim, Reference Jenkins and Kim2024). Lee Jun-seok resonates with young male voters not just through his age but also his strong personality, aggressive leadership, and comments regarding reverse discrimination that appeal to this young demographic (Lee, Reference Lee2024).

In this way, young people’s preferences, particularly young men, are changing because they are tired of traditional politics and traditional leadership and the familiarity of established politicians. Growing support for strongman leadership among young Koreans does not stem from a history of political socialisation (Easton, Reference Easton1968) nor does it stem from authoritarian nostalgia or the Park Chung-hee syndrome, like their older counterparts who may be haunted by lived experiences with an authoritarian past; it is a relatively new phenomenon that stems from their current grievances in the current political climate.

2.2.2. Intergenerational disparities towards strongman leadership: the economic factor

From an economic perspective, however, Park’s dictatorship may be viewed a bit more favourably among the older generation. The Park regime is often associated with driving economic growth through state-driven industrialisation, creating one of the most rapid and successful economic booms in South Korea that led one of the poorest economies in the world to becoming one of the wealthiest (Kim, Reference Kim2014; Kang, Reference Kang2016; Kang, Reference Kang2018; Hong, Park, and Yang, Reference Hong, Park and Yang2023). Older individuals may also remember their own personal financial gains during this period, where hard work led to not just economic gains but also allowed their families to flourish.

This reinterpretation of the past dictatorship through a nostalgic lens has been described as the ‘Park Chung-hee syndrome’ (Choi and Woo, Reference Choi and Woo2019). Despite this, the older group of ‘nostalgic nationalists’ (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022) is likely to be relatively small compared to the broader older population due to the memories of the harsh realities of Korea’s past authoritarian regime. The former dictator’s regime is, in this way, remembered as a ‘double-sided phenomenon’ where there was a successful economic rise, but simultaneous extreme repression within society. Consequently, older Koreans who have seen Korea’s economy flourish in less repressive eras as well may be less likely to support a strongman leader relative to a democratic one.

Among young Koreans, however, economic grievances are likely to take a large toll on decreasing support for traditional, democratic leaders and increasing support for strongman leaders. While political grievances in the current climate may be relatively similar across different generations, young Koreans are more likely to feel a sense of relative deprivation compared to their older counterparts financially, particularly as they feel economically disadvantaged and ‘left behind’ (Foa, Reference Foa2021; Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2019). This stems from growing frustration with their current circumstances and declining opportunities. Despite outstanding educational achievements, many young individuals grapple with challenges such as a shortage of promising job opportunities and worsening unemployment (Cho, Reference Cho2015). Korea currently tops OECD countries with low levels of employment among young adults, where 20.3 per cent of those in their mid to late 20s are unemployed in part due to low levels of economic growth as well as declining entry-level hires by companies, and many of these individuals have been unemployed for at least three years, further adding onto their frustrations (Kim, Kwon, and Kim, Reference Kim, Soon-Wan and Seo-Young2024; Yoon, Reference Yoon2024). While over 70 per cent have college degrees, many are overqualified for most jobs (Loh and Koh, Reference Loh and Koh2023). According to The Chosun Daily, for example, interviews with young individuals in the ‘MZ generation’ (those now in their 20s and 30s) suggest that adequate employment is getting even harder to find. According to the article, some individuals have never been employed since graduating from college and continue to live with their parents while others are unable to save money due to delayed employment (Kwon, Han, and Lee, Reference Kwon, Han and Lee2024).

This lack of job security is further compounded by the fact that this generation struggles with housing insecurity due to soaring real estate prices (Kang, 2023). Considered to be the ‘Generation of House Poor,’ young Koreans are no longer able to purchase homes like that of older generations due to skyrocketing housing prices. Statistics suggest that housing prices have increased to the point where young Koreans in their 20s need more than 85 years of wage earnings to purchase an apartment (The Korea Times, 2024), leading this generation to be called the ‘kangaroo tribe’ as many live with their parents due to unaffordable housing (Loh and Koh, Reference Loh and Koh2023). Dissatisfied with their uncertain future, young Koreans have dubbed Korea ‘Hell Joseon’ and themselves the ‘giving up generation’ or the ‘n-po’ generation, giving up various ‘basic’ aspects of life, including love, marriage, and childbirth (Jones, Reference Jones2023).

In this way, there is an intergenerational economic disparity, where young Koreans feel relatively deprived compared to their older counterparts, whom they perceive as having had more opportunities for a better life, even though the expectation is often the opposite. “Compared to the previous generation, when a rags-to-riches story was possible, this young generation became the first generation to be poorer than their parents,” (Kang, 2023). This is even though younger generations are better educated and live in a more comfortable democratic environment than previous generations. Due to this, they are increasingly disillusioned with existing institutions that fail to improve their daily lives, particularly in relation to overcoming economic hardships (Kang, 2023), and are becoming increasingly disillusioned with democracy. From their perspective, the promises being made by traditional politicians are going unfulfilled.

In such circumstances, leaders with authoritarian tendencies can appeal to young Koreans grappling with growing fear and vulnerabilities, particularly in terms of job security (Eom and Kwon, Reference Eom and Kwon2023). That is, this sense of economic disparity fuels not just frustration and disappointment with leaders who they believe do little to support them, but it also increases isolation, and strongman leaders can attract this. Strongman leaders can capitalise on public discontent with existing institutions by addressing societal problems and repeatedly promising to ‘fix’ issues such as unemployment. This resonates with young voters frustrated with their current circumstances. Moreover, these leaders reassure voters and project reliability by pledging swift action, enhanced responsiveness, and claims of superior performance compared to the current environment. They often convey these messages in charismatic and appealing ways. This appeal is especially potent among young people dissatisfied with the perceived failure of the existing democratic system to meet their expectations, frustrated with traditional politics, and increasingly anxious about the perceived lack of opportunities. Thus, this perception of relative deprivation leads them to find alternative leadership styles more appealing.

2.2.3. Summarising intergenerational disparities within political and economic factors

In this manner, it is possible that both the older and younger generations can view strongman leaders favourably. However, older Koreans may be less likely to view strongman leaders favourably due to their own experiences with, and history of, political repression that outweigh economic benefits. Contrarily, younger generations seemingly harbour growing political and economic grievances towards current institutions and political leaders because of their perception that the existing institutions do not give them the opportunities they need to grow. Additionally, younger generations did not experience a difficult, repressive past and are not haunted by the same fears as older generations are. As such, these significant intergenerational disparities, from both political and economic factors, significantly influence attitudes towards strongman-type leaders who do not fit the traditional democratic mould.

2.3. Main argument

As such, this study makes two key arguments. First, it argues that Korean citizens are unlikely to support strongman leaders due to the dictatorship nature of their rule and the history of authoritarianism that continues to haunt the country. This may particularly be the case among older individuals relative to younger ones. They may generally be more likely to support democratic leaders who uphold checks and balances because Korea is a relatively newer democracy since it democratised during the third wave in 1987, and because Korea is a consolidated democracy that continues to flourish through the democratic orientations of its citizens. While authoritarian nostalgia may exist, it is relatively minimal.

Second, compared to older citizens, young individuals are more likely to be receptive to strongman leaders who disregard democratic procedures. This is a relatively recent phenomenon, and it can be attributed to young voters’ growing fears and anxieties over their economic and political opportunities, and through this, their desire for alternative forms of leadership that seem to work more in their favour. Moreover, strongman leaders are able to appeal to the youth and their vulnerabilities.

In this way, the two hypotheses show that Korea may not generally be severely struggling with democratic backsliding when considering the sentiment of the general public, as has been suggested in previous literature (Shin, 2018; Shin, Reference Shin2020) and it does not seem to follow the trend that can be observed in other parts of the world (Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2016; Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2017). Still, there is a clear contrast in terms of changing sentiment among young Koreans. This contrast thus shows that the youth and changing sentiment towards strongman leaders may play a critical role in Korea as they become the largest voices in the adult electorate in the years to come. In this way, the hypotheses for this study are as follows:

H1 The Korean public, in general, is less likely to support a strongman leader who disregards democratic procedures compared to a democratic leader who upholds checks and balances.

H2 Young people are more receptive to a strongman leader who disregards democratic procedures compared to older individuals.

3. Data and methods

To test our hypotheses, we conducted an original survey using Lucid Marketplace.Footnote 1 The 10-minute survey collected a sample of about 1,039 respondents from May 10, 2022, to May 17, 2022. This time period was chosen as the 2022 South Korean presidential elections took place in February, with former President Yoon’s inauguration in May, making the survey timing crucial for gauging support for different types of political leadership.

The survey included demographic questions and questions related to political attitudes and support for democratic and autocratic principles.Footnote 2 This included one of our main variables, age, as well as items measuring respondents’ perception of the current state of democracy in the country (rated on a scale from 1 to 10), the perceived importance of various principles of democracy, and the importance of various democratic attributes within South Korea. Specifically, we included questions about whether attributes such as free elections, military intervention in politics, gender equality, religious leadership, and civil rights were essential to democracy (see appendix for full question wording). In addition, the survey included descriptive questions based on personal preferences and asked respondents how important they considered the following aspects within the Korean context (see appendix for full question wording):

-

‘The media can report the news without censorship’.

-

‘Women have the same rights as men’.

-

‘A strong leader can disregard parliament and elections and make decisions’.

-

‘Honest elections are held regularly with a choice of at least two political parties’.

-

‘There is a judicial system that treats everyone equally’.

-

‘Strong civic movements protect democracy’.

-

‘Opposition parties can operate freely’.

To further test our hypotheses, we embedded a survey experiment to assess support for different types of political leadership.Footnote 3 We focused on two leadership types and randomly assigned respondents to one of two vignettes: one depicting support for a democratic leader and the other depicting support for a strongman leader.Footnote 4 Both vignettes featured a South Korean leader, a highly educated scholar with multiple years of research experience. The first vignette (i.e. the control group) presents this scholar as posting on social media that a political leader must ensure checks and balances within the government, indicating support for democratic leadership. In the second vignette (i.e. the treatment group), the scholar states that a political leader needs to be strong-willed and should not be confined by rules and norms during crises, indicating support for a strongman, authoritarian leader.

-

Vignette 1: Support for Democratic Leadership

‘A’ is a leading academic and columnist in South Korea. He/she is a highly educated scholar with multiple years of experience in research.

Recently, on his/her SNS account, he/she posted that a political leader needs to ensure that checks and balances are in order within the government.

-

Vignette 2: Support for Strongman Leadership

‘A’ is a leading academic and columnist in South Korea. He/she is a highly educated scholar with multiple years of experience in research.

Recently, on his/her SNS account, he/she posted that a political leader needs to be strong-willed and should not be confined to rules and norms at the time of crisis.

Respondents were then asked to rate how acceptable or unacceptable they found the columnist’s statement, with options ranging from completely acceptable to completely unacceptable (see appendix for full question wording). This allowed us to isolate and test the effect of support for democratic versus strongman leadership.

4. Descriptive and regression results

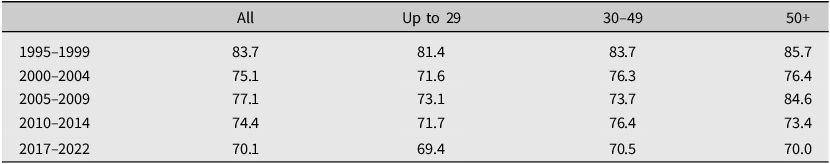

First, we present descriptive statistics on these survey items to gauge the understanding of, and support for, democracy as a form of government. When asked whether respondents view South Korea as undemocratic or democratic, Table 2 shows that the average score was 6.3 on a scale from 1 to 10, indicating a lukewarm response to the country’s current level of ‘democratic-ness’. Younger respondents had an average score of 6.3, while older respondents averaged 6.4, showing very little to no significant difference by age.

Table 2. Democratic-ness of country by age

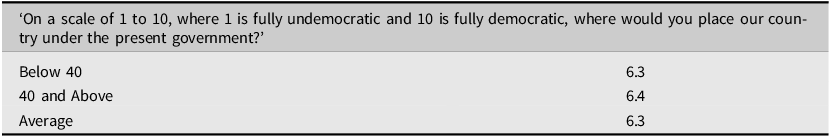

Regarding the essential characteristics of a democratic country, however, the majority of respondents seemed to have a clear conceptualisation of democracy as a form of government. Figure 1 shows that a large majority of respondents (approximately 90 per cent) believed that ‘free elections’ and the ‘protection of civil rights’ were essential, while 76.4 per cent considered gender equality essential. Though some autocratic traits were also included in this question, not many respondents viewed these traits to be democratic. Slightly over a quarter (28.8 per cent) of the respondents believed that ‘religious authorities interpreting the law’ was essential to democracy, while only 17.6 per cent considered ‘army rule’ essential. While the majority demonstrated an accurate understanding of democracy, only some viewed autocratic traits as essential within a democratic government, indicating a high level of cognitive democratic understanding.

Figure 1. Essential characteristics of democracy.

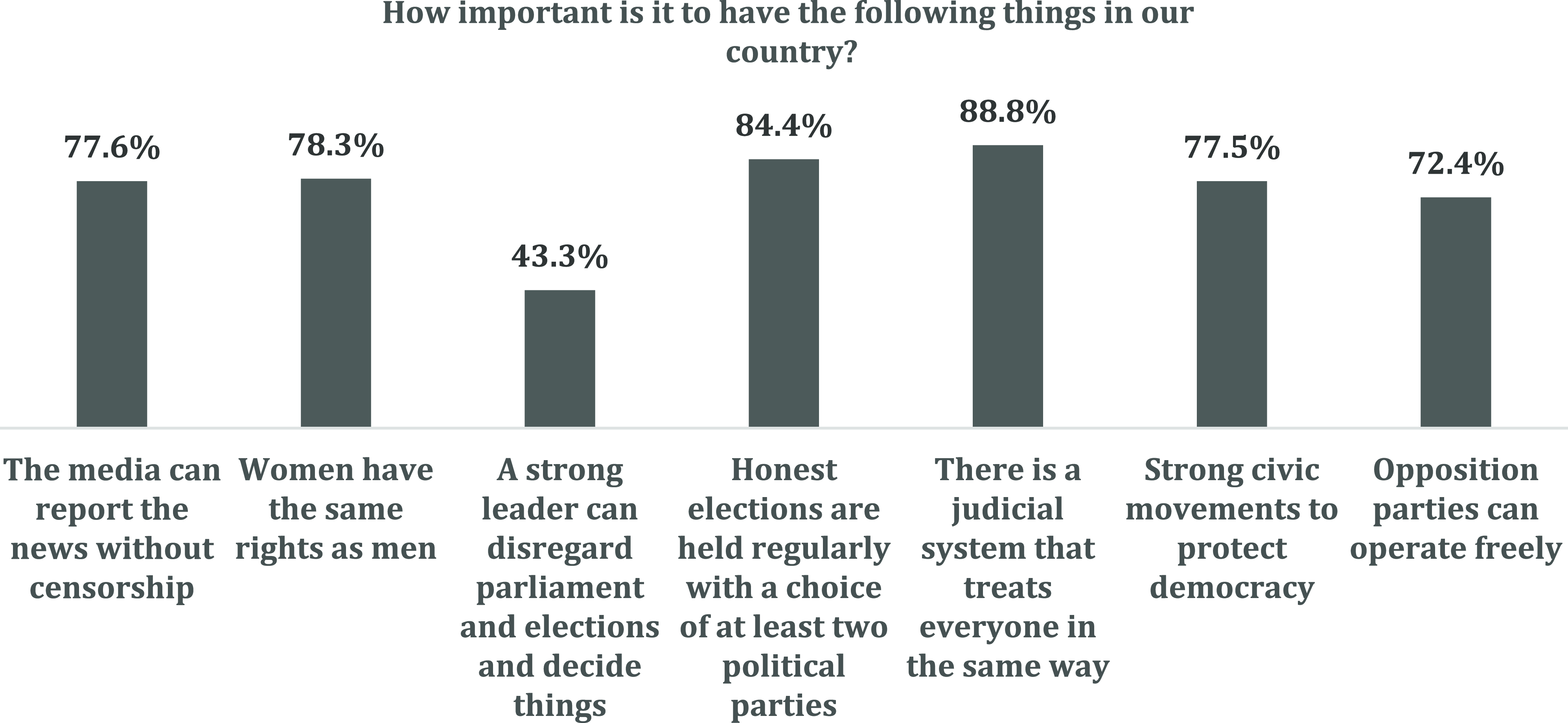

Additionally, respondents were asked which traits are important for Korea specifically. Figure 2 shows that a majority believed that general democratic properties were essential and important. In terms of ranking, more respondents indicated that ‘a fair judicial system’ was more essential than other properties, followed by ‘free and fair elections’, ‘gender equality’, ‘free media’, ‘civic movements’, and ‘a fair multiparty system’, respectively. However, when asked about ‘strongman leadership’, specifically, less than half considered it important for Korea. Interestingly enough, this was the only trait that was not considered important to have in South Korea, despite the surge in support for this type of leadership among younger individuals. This suggests that, in general, there is little support for a strongman leader among the general public.Footnote 5

Figure 2. Importance of democratic properties.

Furthermore, the descriptive results suggest that Korean citizens largely have a clear understanding of, and support for, democracy as a form of government. This suggests that, as Hypothesis 1 contends, there is still relatively high support for democracy among the general public. In the same vein, it also signals that non-democratic properties, such as strongman leaders, are viewed to be less important.

Moreover, increasing support for strongman leadership, relative to the expected and traditional support for democratic forms of leadership, is a new and unique phenomenon, as support seems relatively high among all age groups. A s shown in Figure 3, data from the 7th wave (2017–2022) of the World Values Survey (WVS) further suggests that 66.8 per cent of the Korean respondents stated that it was ‘very good’ or ‘fairly good’ to have a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections, with very little difference by age groups. In fact, 62 per cent of those below 30 believed it was good while 67.4 per cent of those below 50 believed it was good to have this type of strongman leader (see appendix for question wording). Though there are small generational differences, in general, the World Values Survey shows that the majority of every age cohort shows support for strongman leaders.

Figure 3. Support for strongman leadership.

Previous waves of the World Values Survey further suggest that support for strongman leadership has increased in recent years.Footnote 6 For example, 48.7 per cent of respondents believed having this type of strongman leader was good in wave 6 (2010–2014), 47.6 per cent believed so in wave 5 (2005–2009), 25.6 per cent believed so in wave 4 (2000–2004), and 31.7 per cent believed so in wave 3 (1995–1999). This further indicates that support has increased in recent years.

4.1. Experiment on support for strongman leadership relative to democratic leadership

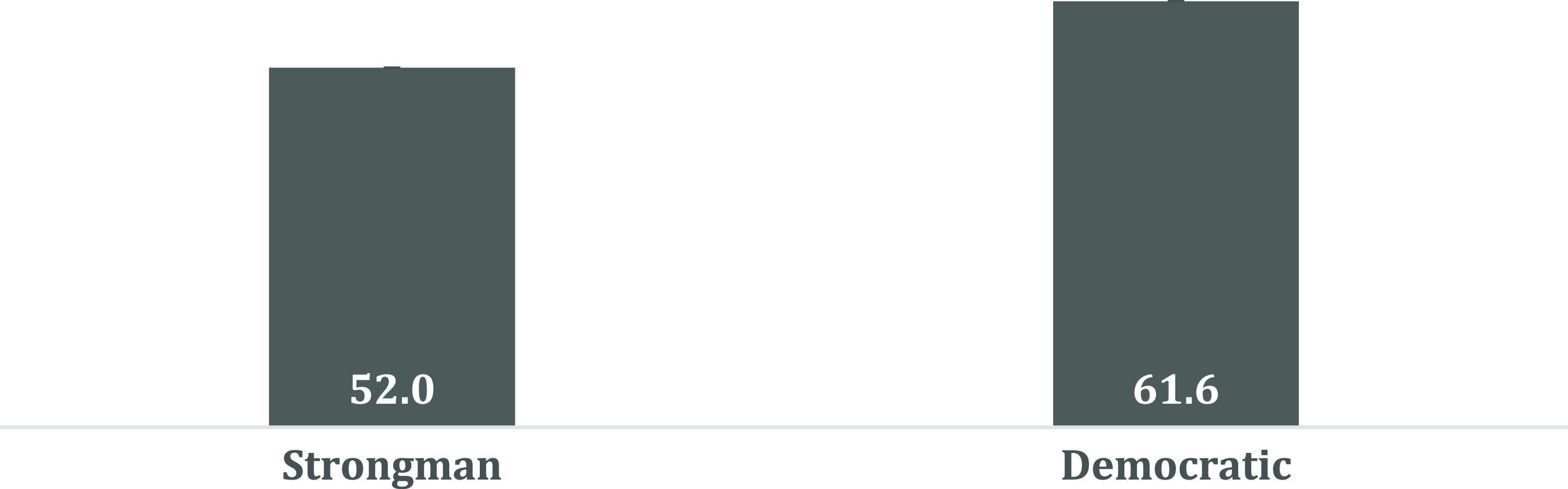

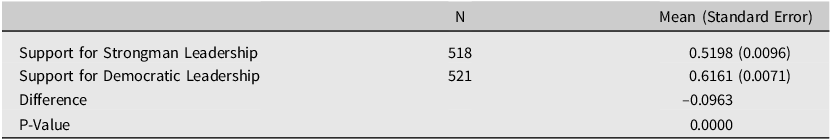

In order to specifically gauge support for strongman leadership compared to democratic leadership, we conducted the survey experiment as described above. We first performed t-tests to examine differences in support for the two types of leaders. The results of the experiment, presented in Figure 4, show respondents’ mean levels of support for a strongman leader who is strong-willed and is not constrained by rules and norms during crises compared to a democratic leader who emphasises ensuring checks and balances within the government. That is, the numbers in the bar graphs indicate the mean scores of the continuous variables (from completely unacceptable to completely acceptable). Because the variables are coded on a 0 to 1 scale, a unit increase thus indicates a greater likelihood to show acceptance of the leader relative to a lesser likelihood of acceptance.

Figure 4. Mean support for strongman and democratic leadership.

In general, Figure 4 shows that the mean support for the democratic leader was higher than for the autocratic leader, with 61.6 per cent support for the pro-democratic leader and 52 per cent support for the strongman leader. In other words, respondents were 9.6 percentage points more likely to support the democratic leader. Though support for strongman leadership was still high, with over half of the respondents showing favourable sentiment, support for the democratic leader was higher. The difference in support, moreover, was statistically significant at the P < 0.000 level, based on a two-sample t-test (see appendix for detailed results).Footnote 7

The results indicate that respondents were generally more supportive of a democratic leader who upholds checks and balances than a strongman leader who is characterised as strong-willed and unconstrained by rules and norms. These results, along with the descriptive statistics, thus lend support to Hypothesis 1. That is, the Korean public, in general, is less likely to support a strongman leader who disregards democratic procedures compared to a democratic leader who upholds checks and balances.

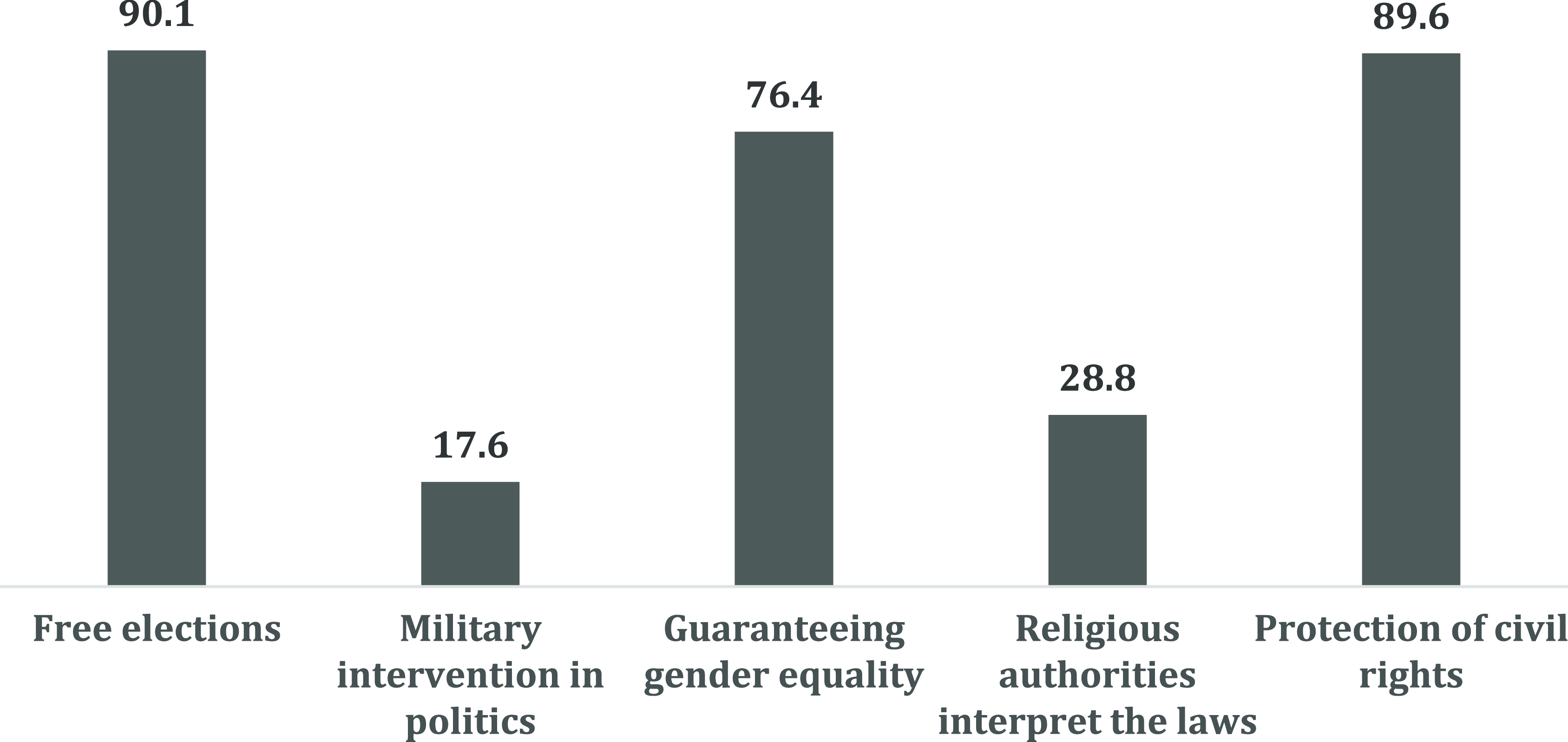

Additionally, to test the second hypothesis, we analysed age differences in support specifically for strongman leaders—that is, we analysed support for leaders who are strong-willed and not confined to democratic rules and norms based on two different age groups. This included the younger group of those below 40 years old and the older group, which consisted of those 40 years old and older. T-tests were conducted to compare differences between the two age groups.

Comparing the two groups, Figure 5 shows that the mean support for the strongman leader among young respondents was approximately 4.7 percentage points higher than older respondents, statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level based on a two-sample t-test. Put simply, younger respondents showed support for strongman leaders while those in the older cohorts showed less support. However, our sample size was smaller for this analysis (see appendix for detailed results). 54.6 per cent of young respondents expressed support for the strongman leader, compared to 49.9 per cent of older respondents. While support among the older group was still somewhat high, those in the younger age cohort showed more support. These results indicate a generational difference in preferences for strongman leadership, with young Koreans appearing more supportive of strongman leaders with authoritarian tendencies than older Koreans. The results thus support Hypothesis 2. That is, young people are more receptive to a strongman leader who disregards democratic procedures compared to older individuals.

Figure 5. Support for strongman leadership by age groups.

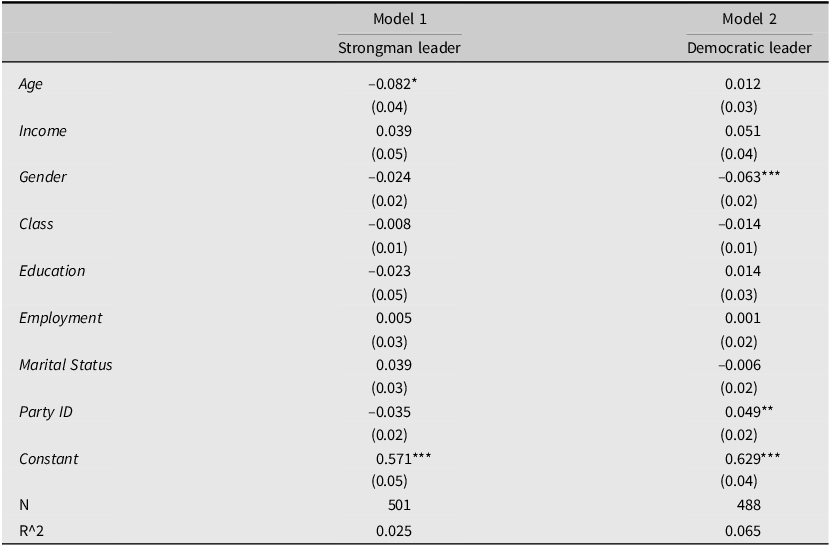

To further our analyses, we conducted multiple ordinary least squares regressions to measure the effects of younger age on support for strongman leadership compared to support for democratic leadership. The regression results in Table 3 show the coefficient scores and the standard errors for each variable in Model 1 and Model 2. The sample size consists of those who received the control and treatment, respectively. That is, those who received the strongman leader vignette were included in the regression regarding support for strongman leader (Model 1), while those who received the democracy leader vignette were included in the regression regarding support for democratic leaders (Model 2). In the regression analyses, rather than using categorical variables, continuous variables were used. This includes the main predictor of age, which reverse-coded age cohorts between 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and 60 and up. Therefore, an increase in the coefficient of the variable Age is correlated to increasing support for either Strongman Leader (Model 1) or Democratic Leader (Model 2).

Table 3. Regression models on support for strongman and democratic leadership

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The results in Table 3 indicate that older age decreases the likelihood of supporting strongman leadership. Moving from younger to older respondents predicted an 8.2 percentage point increase in support for strongman leadership, significant at the P < 0.05 level. Similarly, we measured the effects of age on support for democratic leadership and found that older age increased the likelihood of supporting democratic leadership by 1.2 percentage points; however, this was not statistically significant. This indicates that, conversely, younger respondents are more likely to show support for strongman leaders relative to older respondents and less likely to show support for democratic leaders, though the latter is not statistically significant. Among the control variables, moreover, gender (male) significantly decreased support for democratic leadership by 6.3 percentage points (P < 0.000) while those who identified themselves as democrats were more likely to show support for democratic forms of leadership, predicting a 4.9 percentage point increase at P < 0.01. Thus, the regression results confirm that age differences influence support for a leader with autocratic tendencies.Footnote 8 Younger respondents were more likely to support strongman leadership than older respondents, while male respondents were less likely to support democratic leadership, and democrats were more likely to support democratic leadership.Footnote 9

5. Discussion

The results of this study are multifaceted. First, there appears to be a clear understanding among Korean respondents regarding democracy’s essential characteristics. The majority viewed ‘free elections’ and the ‘protection of civil liberties’ as essential characteristics, while ‘military intervention’ and ‘religious interpretations of the law’ were not deemed essential. In terms of personal preferences for government characteristics, a majority supported various democratic features such as ‘multiparty systems’, ‘gender equality’, and ‘free and fair elections’. In contrast, less than half expressed support for strongman leadership. This contrasts with existing studies suggesting low cognitive, affective, and behavioural support for democracy among Korean citizens (Shin, Park, and Jang, Reference Shin, Park and Jang2005; Cho, Reference Cho2014) and implies that the trajectory away from democratic leadership is not due to a lack of information or awareness about democracy but rather stems from negative emotions that act as deterrents to supporting democratic leadership.

The embedded survey experiment indicates that while respondents generally favoured pro-democratic leaders over strongman leaders, more than half (52 per cent) still expressed support for strongman leadership. Additionally, over half of young respondents (around 55 per cent) were more likely to support strongman leaders compared to older respondents (around 50 per cent). Multiple regression analyses further validate these results, showing that young respondents are more likely than older respondents to support strongman leaders and less likely to support democratic leaders.

Indeed, support for democracy does not significantly vary across age groups, but support for strongman leadership does statistically and significantly vary. As we originally suggested in our second hypothesis, young individuals are seemingly more receptive to strongman leaders in part because these leaders seem to appeal to their vulnerabilities. These leaders give off the impression that they will resolve problems that young people constantly struggle with. The regression results suggest that this may be the case by showing a negative and significant correlation between older age and support for strongman leaders, indicating that older respondents are less likely to support these leaders relative to younger respondents. However, there is a positive correlation between older respondents and support for democratic leaders that is statistically insignificant. This suggests that it is unclear whether young people prefer democratic leadership relative to older individuals; however, young individuals seemingly show more favorability towards strongman leaders relative to older individuals and seem more open to alternative forms of government from democracy. Additionally, due to the group breakdown, it also indicates that the vignette regarding strongman leaders may have been more effective in increasing favourability among young individuals relative to older individuals, though this does not seem to be the case among support for democratic leaders.

This contrasts quite a bit with other countries worldwide experiencing democratic backsliding and growing dissatisfaction with democracy (Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2019, Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Wenger, Rand and Slade2020; Claassen and Magalhães, Reference Claassen and Magalhães2023) and instead suggests that Korea’s democracy is struggling in unique ways, with one being this increasing support for strongman leaders among young Koreans. This is despite the fact that the youngest generation is often the most likely to push for democracy and the least likely to support authoritarian alternatives in the country. Due to high levels of education among the youth, it seems as though young Koreans may possibly still find value in democratic institutions. Additionally, the term democracy carries a positive connotation, which may help the regime maintain support among the general public. However, support for strongman leadership is simultaneously growing among young individuals. This suggests that, like in other parts of the world (Foa and Mounk, Reference Foa and Mounk2019), while support for democracy overall may not significantly vary, there is variation in support for different aspects of democratic institutions. In this way, the youth in Korea may be growing sceptical of democratic leadership. This contrasts significantly with older generations, and this growing generational gap in Korea thus suggests that polarisation is manifesting itself in concerning ways.

These findings thus empirically challenge the long-held assumption that young Koreans wholeheartedly prefer democracy, democratic leadership, and democratic institutions in Korea. Broadly speaking, these findings paint a somewhat concerning view of Korea’s democratic future. Many young voters do not find strongman leaders appealing due to authoritarian nostalgia and a romanticised view of the past, which may resonate with older voters given South Korea’s authoritarian legacy, nor do they find this type of leadership appealing because of these leaders’ populist tendencies. Rather, young Koreans are seemingly drawn to strongman leaders due to their disillusionment with the declining quality of political leadership in the country, in part due to their growing grievances over socioeconomic inequalities and a society characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. They are, ultimately, disappointed with the lack of opportunities bestowed upon them, despite their own skill sets and capabilities. As a result, they are looking for alternatives that may work better to their advantage.

Since young Koreans are crucial to the future of Korean democracy, these findings indicate that, like in many other countries, democracy in Korea may be in crisis, with the potential for democratic backsliding or even democratic decay over time (Shin, Reference Shin2020). Numerous forces can ‘affect a democracy’s survival chances, [but] no democratic regime can stand long without legitimacy in the eyes of its own people’ (Chang, Chu, and Park, Reference Chang, Chu and Park2007: 66). This is especially the case if it is the young voters, ones that will be responsible for Korea’s democratic future. The increasing support for strongman, authoritarian leadership among young voters suggests that Korea may be following the global trend towards a democratic retreat, as the success of a genuine democracy significantly depends on popular support (Inglehart and Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2010). Consequently, these results compel us to rethink how the changing values of the young generation may influence the democratic landscape in Korea in the coming years.

6. Conclusion

Strongman leadership has emerged as a prominent global trend in the 21st century, fundamentally altering global politics (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022). Many leaders exemplify this type of leadership, contributing to the growing phenomenon. While leaders like Putin have been described as ‘the archetype and the model for the current generation of strongman leaders’ (Rachman, Reference Rachman2022), other strongman leaders have risen to prominence internationally in recent years. This trend indicates the rise of a new generation of strongman leaders who wield significant influence in global affairs by participating actively in major international decisions.

Several factors have contributed to the emergence of strongman politics worldwide, including perceived reliability, and promises of systemic change with quick-fix solutions to pressing issues. Irrespective of the reasons, the inevitable consequences are clear: strongman leaders and their movements have undermined democratic institutions, fuelled societal polarisation, and facilitated the spread of authoritarianism. The hypermasculine and hubristic behaviour of strongman leaders has existed throughout history, but the surge in support for strongman politics in recent years appears to coincide with the broader global trend of democratic regression. Moreover, the evolving and adaptable nature of strongman leadership, along with the growing public discontent with democratic institutions, is placing immense strain on consolidated democracies, posing a significant threat to liberal democracy worldwide (Beck, 2020). Strongman leaders now exist in democracies as well as nondemocracies, and the prominence of this type of leadership continues to grow, leading to significant concern regarding the sustenance of a liberal democratic order worldwide. Indeed, ‘democracy ... has been in retreat globally for seventeen consecutive years … [and] the world is less democratic than it has been at any time since 1997’ (Acemoglu, Reference Acemoglu2024).

This trend is also evident in South Korea, where support for democratic and strongman leadership appears to be shifting. This study examined these dynamics, revealing generational differences in support for different leadership styles. While the general public seems to largely support democratic leaders, the young demographic has become a puzzling fixture in the political landscape. Their declining engagement with democracy and increasing support for strongman leadership represent a relatively new phenomenon, one that is concerning for South Korea’s democratic future.

Of course, the study has some limitations that warrant acknowledgement. Going forward, it is essential to unpack differences among various groups within the youth demographic. In particular, there could be significant variations in support for strongman leaders between young women and young men. Recent studies suggest that deepening and growing pessimistic perceptions regarding the economy are fuelling grievances among young Korean men, and in particular, influencing their attitudes towards gender equality (Kim and Park, Reference Kim and Park2024; Kim and Lee, Reference Kim and Lee2022; Kim and Kweon, Reference Kim and Kweon2022; Jenkins and Kim, 2024). As a result, it is likely that gender differences exist among young Koreans in terms of support for strongman leadership. Additionally, it is important to update the results with more recent surveys to assess how support has changed over the past two years, shedding light on the volatility of support for these leaders. Further survey experiments should also compare the impact of different societal grievances on young respondents’ support for strongman leaders. A more detailed analysis or explanation regarding this, and finding the human dimension to these statistical findings, can further be enhanced through qualitative anecdotes or quotes, either through self-conducted interviews or open-ended survey questions that can ask more specific questions. Moreover, expanding this research beyond Korea to include other countries in the region, such as Japan and Taiwan, is important.

Even beyond this, it would be helpful to examine the relationship between young individuals and strongman leaders worldwide, especially in relation to the strongman leaders who have appeared and gained momentum in the past decade. Though a case study analysis would be useful, a comparative global analysis could also provide a significant contribution regarding this trend among young individuals. This could be done through a cross-country survey analysis that includes a survey experiment as well as an oversample of young individuals. However, secondary survey databases such as the World Values Survey, as well as regional barometers, such as the Asia Barometer Survey, could also be useful in the analyses since they incorporate survey items related to strongman leaders and democracy. As such, going forward, additional studies should provide a comparative in-depth analysis of this trend both regionally and globally. This comparative assessment can reveal whether increasing support for strongman leadership among the youth is a country-specific phenomenon due to increasing societal grievances or a broader trend observed in other democracies in the region.

This may be particularly important as the success of authoritarian leadership in one country can ‘shatter democratic norms’ in neighbouring countries as well (Chan, Reference Chan2024) and have a spillover effect. In certain ways, this trend seems to be more visible in Korea than neighbouring areas, as the combination between democratic backsliding and the resurgence of authoritarianism, or even authoritarian nostalgia (Kim-Leffingwell, Reference Kim-Leffingwell2023), seems to be coming back in full force in Korea. This is especially concerning since there are authoritarian strongman leaders in neighbouring countries, and increasing support for this type of leadership in a consolidated country like South Korea could lead to further growth of this type of leadership in other democracies throughout the region. As a result, it is better to examine whether this phenomenon is unique to Korea earlier rather than later.

In order to foster positive attitudes towards democratic leadership and reduce support for strongman leaders, democratic institutions must do more to protect and support the young generation, as this demographic is poised to play a critical role in the country’s democratic future. Additionally, political leaders need to engage directly with this generation, actively communicating to ensure they do not feel left behind. Most importantly, democratic institutions must enhance job security, improve employment opportunities, and provide avenues for socioeconomic advancement (Eom and Kwon, Reference Eom and Kwon2023). These changes could not only strengthen support for democratic leaders but also reinvigorate the young generation’s involvement in democratic processes, allowing them to once again be at the forefront of democratisation. By addressing these concerns, the value orientations of young Koreans could potentially lead Korea towards a brighter, more democratic future.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Sogang University Research Grant of 202310037.01, and by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022S1A3A2A02090384).

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. World Values Survey:

‘I’m going to describe various types of political systems and ask what you think about each as a way of governing this country. For each one, would you say it is a very good, fairly good, fairly bad or very bad way of governing this country?’

-

a) Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections

-

b) Very good

-

c) Fairly good

-

d) Fairly bad

-

e) Very bad

Appendix B. Matrix Grid Qs: Please tell me for each of the following things how essential you think it is as a characteristic of democracy. Use this scale where 1 means ‘not at all an essential characteristic of democracy’ and 100 means it definitely is ‘an essential characteristic of democracy’

-

a) Free elections

-

b) Military intervention in politics

-

c) Guaranteeing gender equality

-

d) Religious authorities interpret the laws

-

e) Protection of civil rights

Appendix C. Matrix Grid Qs: How important is it to have the following things in our country? (very important → not at all important)

-

a) The media can report the news without censorship

-

b) Women have the same rights as men

-

c) A strong leader can disregard parliament and elections and decide things

-

d) Honest elections are held regularly with a choice of at least two political parties

-

e) There is a judicial system that treats everyone in the same way

-

f) Strong civic movements to protect democracy

-

g) Opposition parties can operate freely

Appendix D. Survey Experiment: How acceptable or unacceptable do you find A’s statement?

-

a) Completely acceptable

-

b) Acceptable

-

c) Typical - neither good nor bad

-

d) Unacceptable

-

e) Completely unacceptable

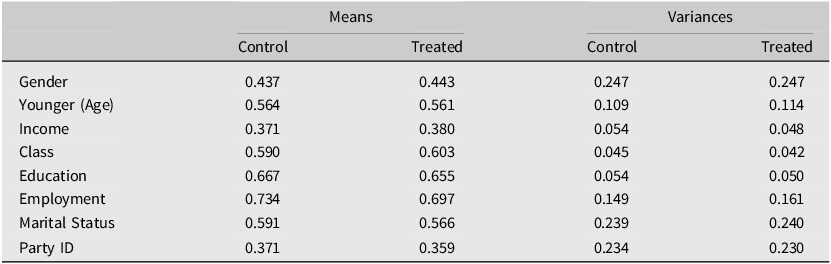

Appendix E. Table for covariate balance checks

Appendix F. T-test results for support for strongman and democratic leadership

Appendix G. Mean support for strongman leadership by age groups