Introduction: True crime podcasts

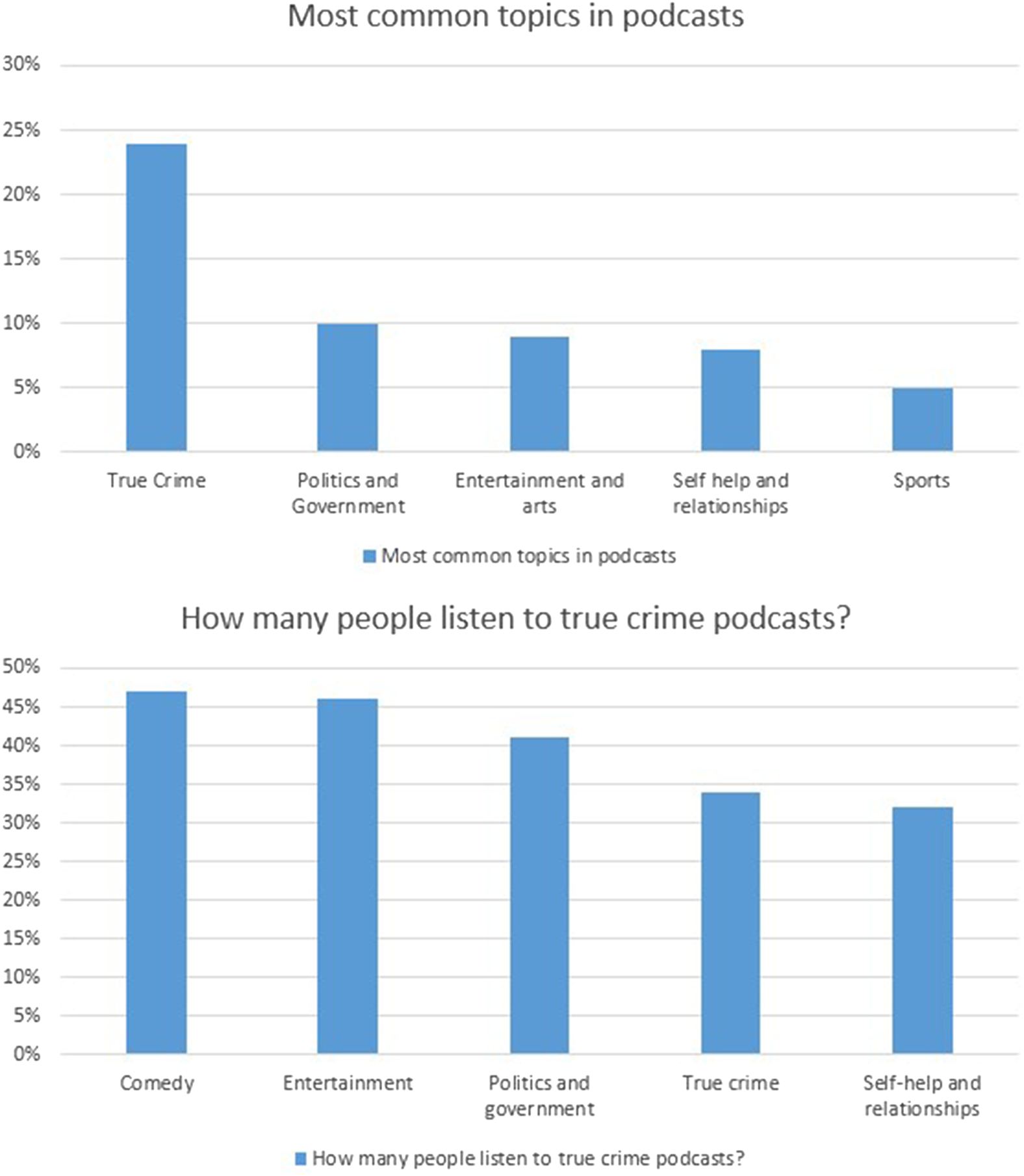

In the landscape of podcast consumption, true crime podcasts are by now among the most popular products: according to Nasser and St. Aubin (Reference Naseer and Aubin2023), in the USA alone (see Figure 1), true crime ranks as the most common topic for podcasts listened to or downloaded, with a third of listeners who either listens or downloads content on their phones, sometimes listening to the same episode more than once, and often engaging in activities within the larger podcast audience community, such as joining a discussion group or a dedicated Facebook page.

Figure 1. Most common topics and average percentage of American listeners to true crime. Adapted from Pew Research Center June 2023.

The interest in true crime has spawned a plethora of TV documentaries (mostly found on Neflix, HBO, Oxygen, Amazon Prime Video, as well as on ‘standard’ digital channels such as the Italian national channel RAI, or the British BBC), developed either as single-unit content or as multi-part stories: in both cases, due to the medium of information, it is assumed that the content will provide a professional insight of the crime presented in the programme, as well as access to thorough information such as interviews with witnesses and police or investigators, opinions and information from other journalists who wrote about the case, and so on. In contrast, true crime podcasts can often be divided into two main categories: the ‘professional’ podcast, usually produced and presented by a journalist supported by a network, and the ‘amateur’ podcast, a (frequently) homemade production featuring one or more hosts who simply talk about a case, in different ways depending on the type of podcast. The number of differences and similarities between these two main categories can lend itself to a more in-depth study of a potential taxonomy of true crime podcasts, which would be beyond the scope of this article; therefore, this short study will only consider the genre as divided into the two main categories just introduced.

The interest in true crime podcasts has risen since the first broadcast of the by-now famous Serial, in 2014, which opened the doors to a seemingly infinite number of podcasters, both professional and amateur, who have spotted a niche that so far was quite unexplored: there are now true crime podcasts that revolve around the presentation of solved cases only; others that explore unsolved mysteries, from murders to disappearances; podcasts that combine true crime and psychology, or true crime and law.Footnote 1 In order to find an opening into what is a very crowded area, some podcasts aim for a more relaxed discussion of a crime, combined with a selection of recommended drinks for the episode (Wine & Crime), or unashamedly declare themselves to be comedy podcasts (True Crime Obsessed), and therefore they bring the level of conversation to a more casual analysis and retelling of a story, with personal comments included in the mix. Finally, some podcasts provide a completely different approach to storytelling, by narrating the crime as if it was a novel, or a spoken book, and involving actors or the podcasters themselves as protagonists, not just raconteurs (Wondery's Young Charlie).

This small study is interested in some of the language that these podcasts use in their episodes, with an initial hypothesis as to the typical features that might be expected: in particular, when considering an amateur podcast featuring two or more hosts, the expectation would be to hear a large number of discourse markers and vague language, as well as self-referential language (with the podcasters often discussing how they feel, or what they think about the episode they are discussing), and potentially, expletives. The corpus analysed should also presumably provide typical examples of crime-related vocabulary, such as murder, victim, witness(es), and so on.

Discourse markers and pragmatic markers

Pragmatic markers such as I mean, you know, ok, tend to be seen as a subcategory of the wider area of discourse markers, in that they act like discourse markers, but with a larger number of functions than more defined discourse markers such as however, or therefore. In fact, although they might sometimes still be called fillers (often in language learning books), they do perform a specific function in discourse and conversation, and can be very versatile in conveying meaning depending on the context they are used. Generally, they act as a link in the interaction between speaker and listener, where the participants or conversants (Schrourup Reference Schourup1985, 5) can share elements of their world in communication: in particular, Schrourup mentions evincives (ibid, 14), lexical items that signal the speaker's participation and engagement in the conversation. While there are several definitions and explanation of this wide range of utterances, this study will focus only on a limited number and range of these interactions, based on the language provided in the podcast episodes analysed.

Pragmatic markers can be sub-divided into primary and secondary (Norrick Reference Norrick2009, 867), where interjections such as oh and uhm are included in the former category, and exclamations such as yeah, well, and okay in the latter; secondary markers also seem to have a slightly wider variety in the class of words, which can include verbs and nouns (damn and boy). A further distinction is made by Ameka (in Norrick Reference Norrick2009, 867), who presents three categories of interjections: the first is based on the speaker's mental state, which is distinguished between emotive or cognitive, and which identifies itself by means of the appropriate marker in the interaction. The second category of interjection is based on the interaction itself, which may require a specific response; and the third category is based on the basic phatic function of the interjection (uhm), where no interaction is required. In general, then, all these markers act as utterances in their own right, meant to convey the internal state of the speaker or as back-channel to the speaker. They can also represent an expression of feeling, notably with words or phrases such as oh my god, fuck, and so on. Ultimately, these markers can be seen within a text as elements that provide information on the discourse, and as such they are part of language and tend to follow a pattern of distribution (for example, yeah would be a response token, while I mean could be a turn-initiator).

The analysis of pragmatic markers needs to take into consideration several factors other than the text type or activity type: Aijmer (Reference Aijmer2013, 3), in presenting the idea of variational pragmatics (Barron and Schneider Reference Barron and Schneider2009, in Aijmer Reference Aijmer2013, 2), includes elements such as gender and age, or communicative language use, in order to determine the function of a specific marker or set of markers. It can also be said that these markers, in their meaning potential, depend on the context and situation in which they are used (Norén and Linell Reference Norén and Per2007, in Aijmer Reference Aijmer2013, 5–6). This means that their meaning will be activated only in the interaction within the context.

The idea of gender as relevant in the use of these markers is quite an interesting one to consider, as the analysis of the corpus in this study will show a very high frequency in words such as like and right. These seem to be very a common linguistic element in superficial analyses of corpus where language is used in informal interactions such as conversations, and allegedly it is seen as typical of one gender more than another, although recent research has been made to disprove this claim (Koczogh and Furkó Reference Koczogh and Furkó2011, 7). This seems to be a research-worthy area for further in-depth study, and has not been included here.

Data collection and research method

The first step in the collection of data for this analysis was to decide which podcasts to use, and how many episodes, or, if the decision was to only use one episode, how many minutes or how many words to input in a corpus and word cloud generator. This relates to what Queen (Reference Queen2015, 58) explains as a subjective decision, based on the questions and the research methods employed.

The choice was to select two episodes from one representative podcast, in their entirety but without the ad breaks, for obvious reasons, and without other extra material that might have featured in the episodes, and which would have provided irrelevant or distracting language for this study. Furthermore, the first few minutes before the episode officially begins are not included in the transcription, as they are generally used for greetings and casual talk between the hosts, before they begin discussing the case, as well as the last minutes, where the hosts usually provide a preview of the next episode and conclude with greetings and (in this particular podcast) bloopers.

The podcast considered for this short study is True Crime Obsessed, whose first episodes date back to 2017, and which is one of the longest running podcasts of this genre. To date, it counts 457 episodes (and counting) on the ‘regular feed’ (which means that listeners can find and listen to these episodes for free), and close to 400 episodes on the Patreon feed, which is a platform accessible only to paying subscribers.

This podcast belongs to the category of ‘comedy’, as the hosts not only discuss a true-crime documentary without providing new information, or a more in-depth analysis of the case, but they also intersperse the commentary with a large amount of personal comments throughout the narration, as well as non-sequiturs, personal anecdotes, and jokes. The discussion itself is relatively superficial, and it only occasionally refers to elements that have been researched further, mostly because of the hosts’ curiosity about a topic.

For the linguistic analysis in this article, two episodes have been taken into consideration, in order to create a small (initial) corpus of just under 20,000 words. A longer study will later consider a much larger corpus, to determine other linguistic factors presumably typical of the genre, and perhaps distinctive of this particular podcast, in comparison to other podcasts of the same genre, such as Crime Junkie. It would in fact be interesting to analyse potential differences related to the sub-genres of true crime (professional or amateur or comedy), or gender differences among the presenters, which is the case with True Crime Garage (two male hosts), Moms and Murders (two female hosts), and indeed True Crime Obsessed (a man and a woman).

Research questions

The study has thus considered these episodes in order to answer some simple questions on the typical language of this sub-genre of podcasts (other than the expected crime-related vocabulary); this follows a concept familiar with discourse analysis, where language is seen as part of a broader system of shared knowledge and culture (Baker Reference Baker2006, 4). For this reason, the research question is concerned with the amount and use of use of pragmatic discourse markers in the samples considered, with a hypothesis to confirm that the final corpus will provide a substantial number of words and phrases in the category of primary pragmatic markers, especially you know, like, right, among potential others, which would confirm the categorisation of the podcast as more amateur than professional, due to the colloquial and conversational style of the hosts’ language. Therefore, this preliminary study aims at answering the question: how many, and which pragmatic markers are typically present in the episodes analysed? The long-term aim is to have enough data for a comparative analysis with podcasts of the same genre and subgenre.

Analysis

True Crime Obsessed (TCO) is self-defined as a comedy podcast, where the two hosts (Patrick Hinds and Gillian Pensavalle) discuss true crime documentaries in a light-hearted way: the homepage of the podcast sums it up as ‘recapping your favourite True Crime documentaries with humor, heart and sass!’. There is no ‘hierarchy’ in the way the podcast is conducted: both hosts work through the notes they have made while watching the documentaries, and discuss the cases while keeping the conversation as light and funny as possible, often interrupting each other, joking, or sometimes even singing. Their interaction is therefore quite informal and friendly, and it includes direct references to the listeners (usually referred to as fam, short for ‘family’) or in-jokes from previous episodes, as well as several other terms used often (girl is one such word, both to refer to each other or to directly ‘talk’ to the protagonists of the case of the week), non-sequiturs and asides to personal stories, and so on. As such, the transcription of the two episodes used for this study turned out to be quite complex, as the software did not always write what the hosts were saying, mostly when they were talking over each other, or if one was laughing while the other was speaking, and this meant that substantial work was required to correct and complete the transcription of the corpus.

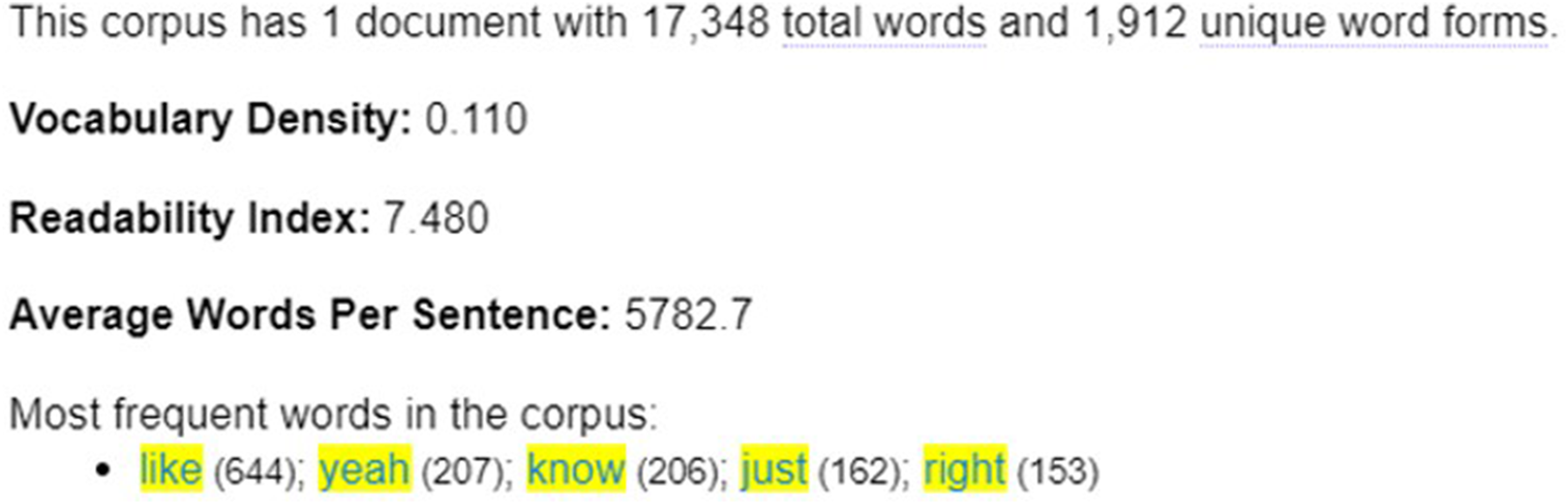

The two episodes chosen date from November 9th and December 14th, 2023, and the corpus amounts to a total of just over 17,000 words; as mentioned above, the first and the last few minutes of each episode were not considered, as well as the excerpts from the documentaries presented, and the ad breaks within each episode.

Some observations are necessary before presenting the results:

Firstly, the episodes have been transcribed in their entirety with use of an AI tool, Voice To Text, a free software which provides a voice-to-text transcription that allowed for faster work, but which also required a number of changes and interventions before the corpus was ready for submission to a word cloud and corpus-analysis generator. Such changes included deleting all names of people and places, as they were not relevant for the analysis and may have been distracting in the final product. This is quite a hybrid approach in comparison to a purely orthographic or phonetic approach (Queen Reference Queen2015, 62), because it means that the texts do not attempt to provide exactly everything that was said; it is also a matter of logistical reasons, as the voice-to-text programme seemed to struggle with personal names, so when correcting those elements, and in consideration of the fact that they were not useful in the analysis, the most logical course of action was to delete them. Another intervention was the correction of spelling mistakes that the voice-to-text software made, such as the transcription ‘he new’ that had to be corrected into ‘he knew’. It is also worth noting that the transcription does not include other linguistic elements such as the very few hesitations (primary markers) such as uh-hu, which although very rare in the episodes, did occur at times in the audio: as the software did not acknowledge them, they have been therefore ignored in the study. Finally, there was no distinction made between the two speakers in the transcription, which means that the text was fed into the word cloud generator as one long stream of words: since the goal was to establish the type and frequency of the markers, it did not seem useful or necessary to distinguish between speakers at this particular moment.

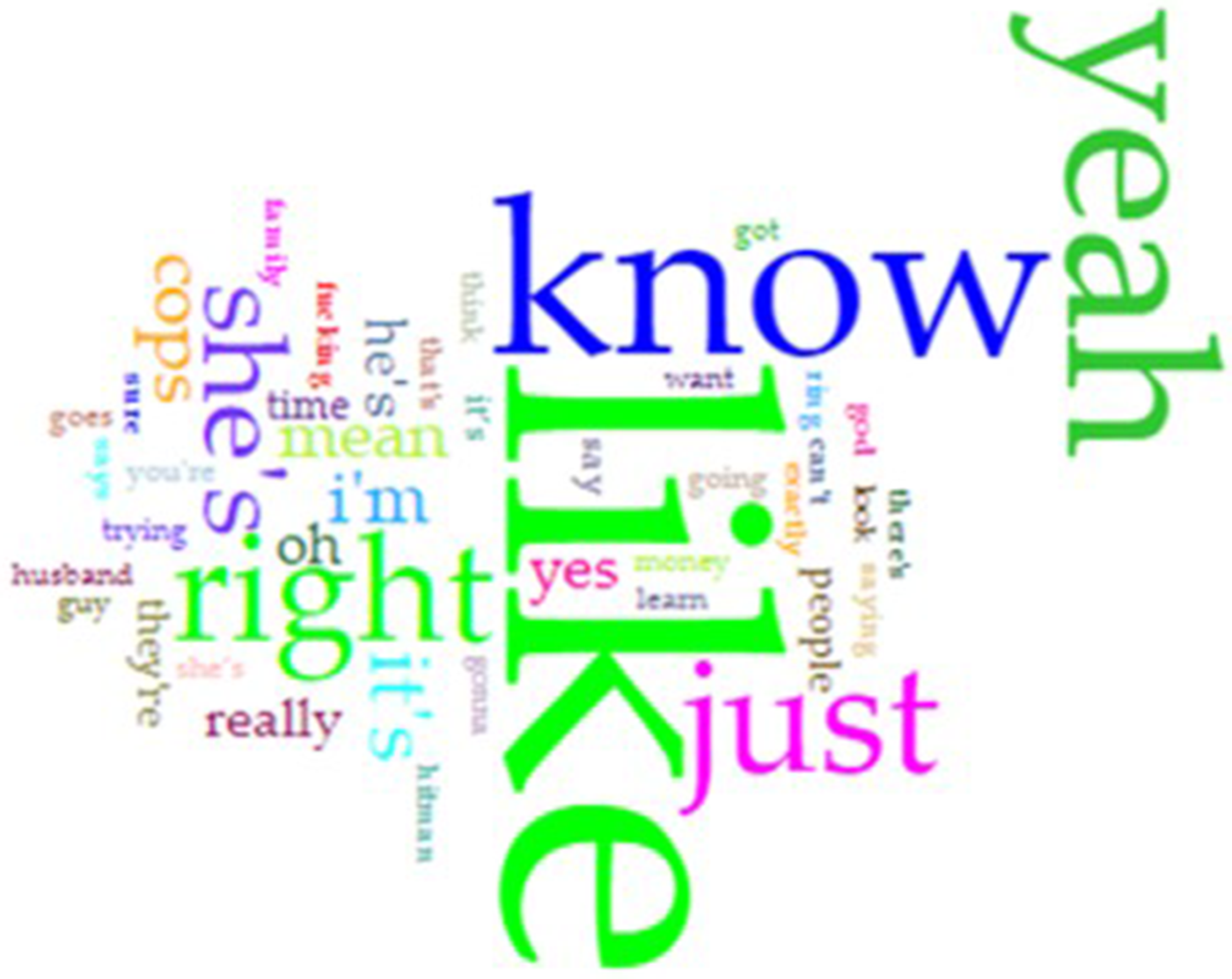

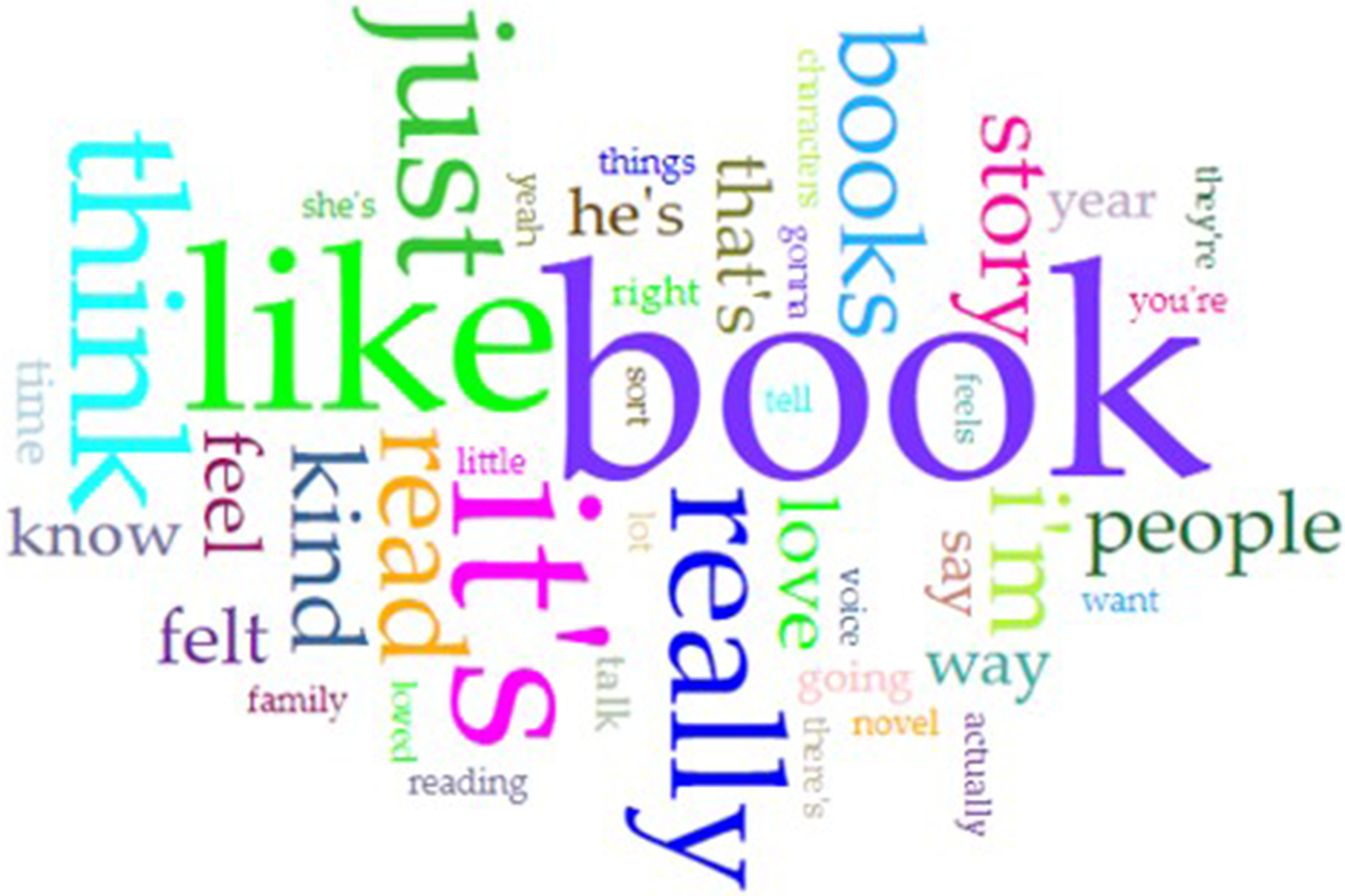

A first overview of the corpus obtained (Figures 2 and 3) shows that the most common word is like; know is the third-most spoken word (mostly as you know and I (don't) know), 206 times against the 207 times of yeah. The wordcloud also highlights the frequent use of the word mean, which is used in context as: I mean, used to rephrase a sentence; in the longer phrase (do) you know what I mean?; and as a kind of exclamation when other words fail to convey the feelings of the speaker (I mean . . .)

Figure 2. Wordcloud of the most frequent words in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

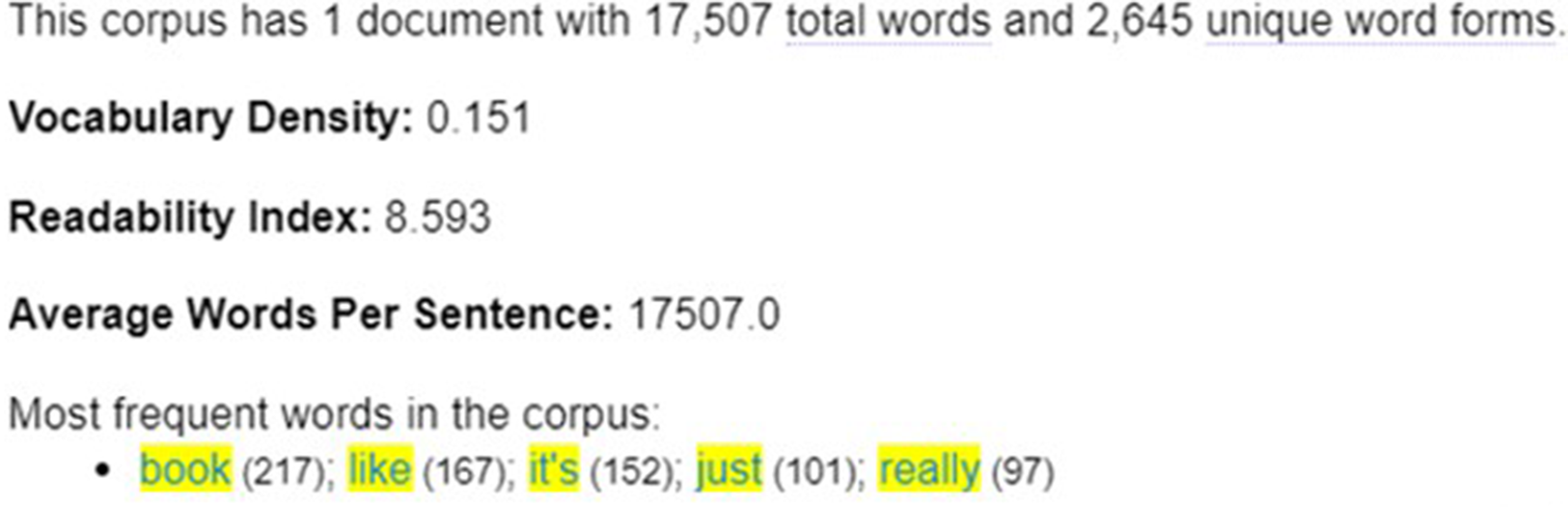

Figure 3. Summary of the most frequent words in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

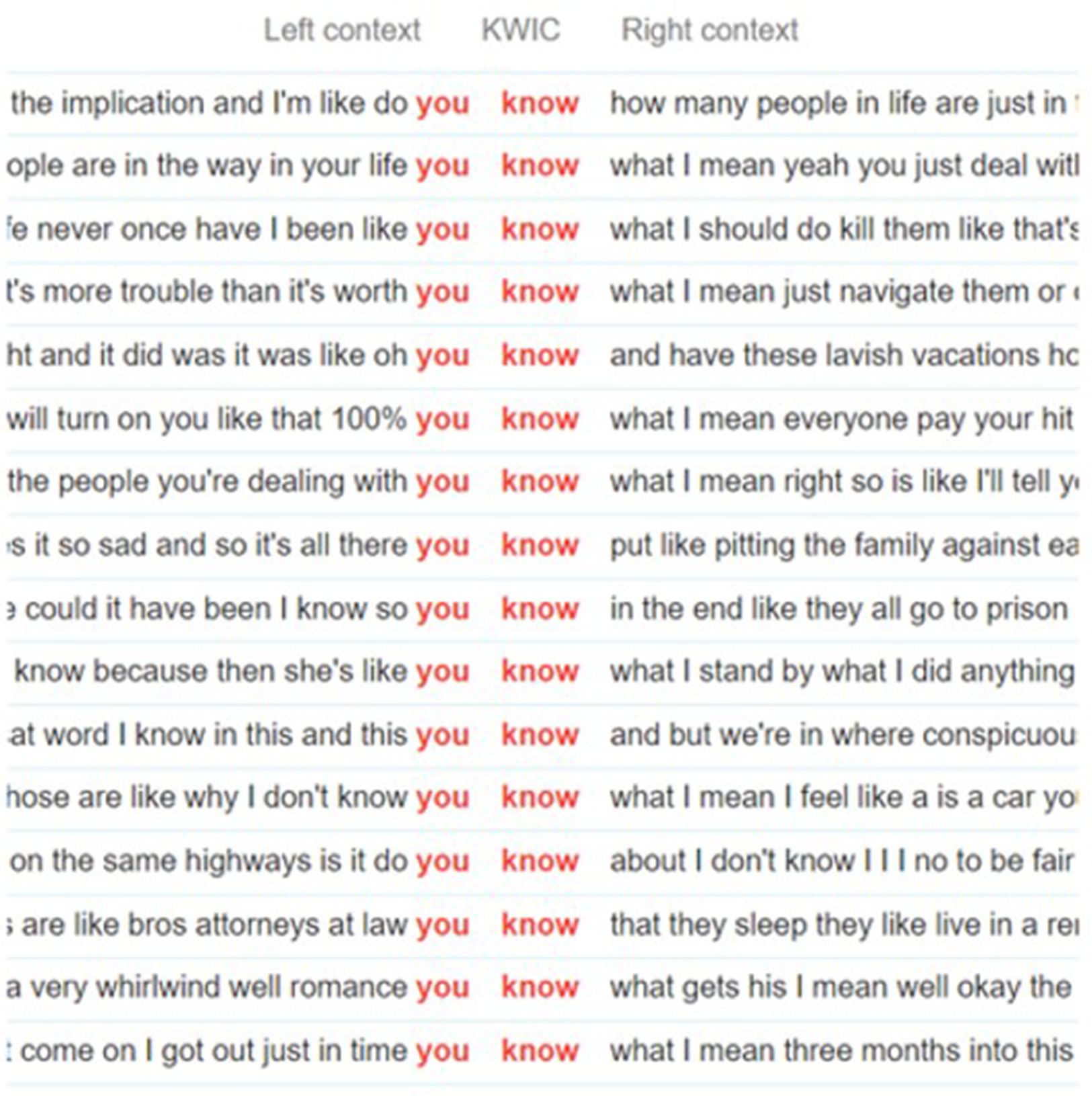

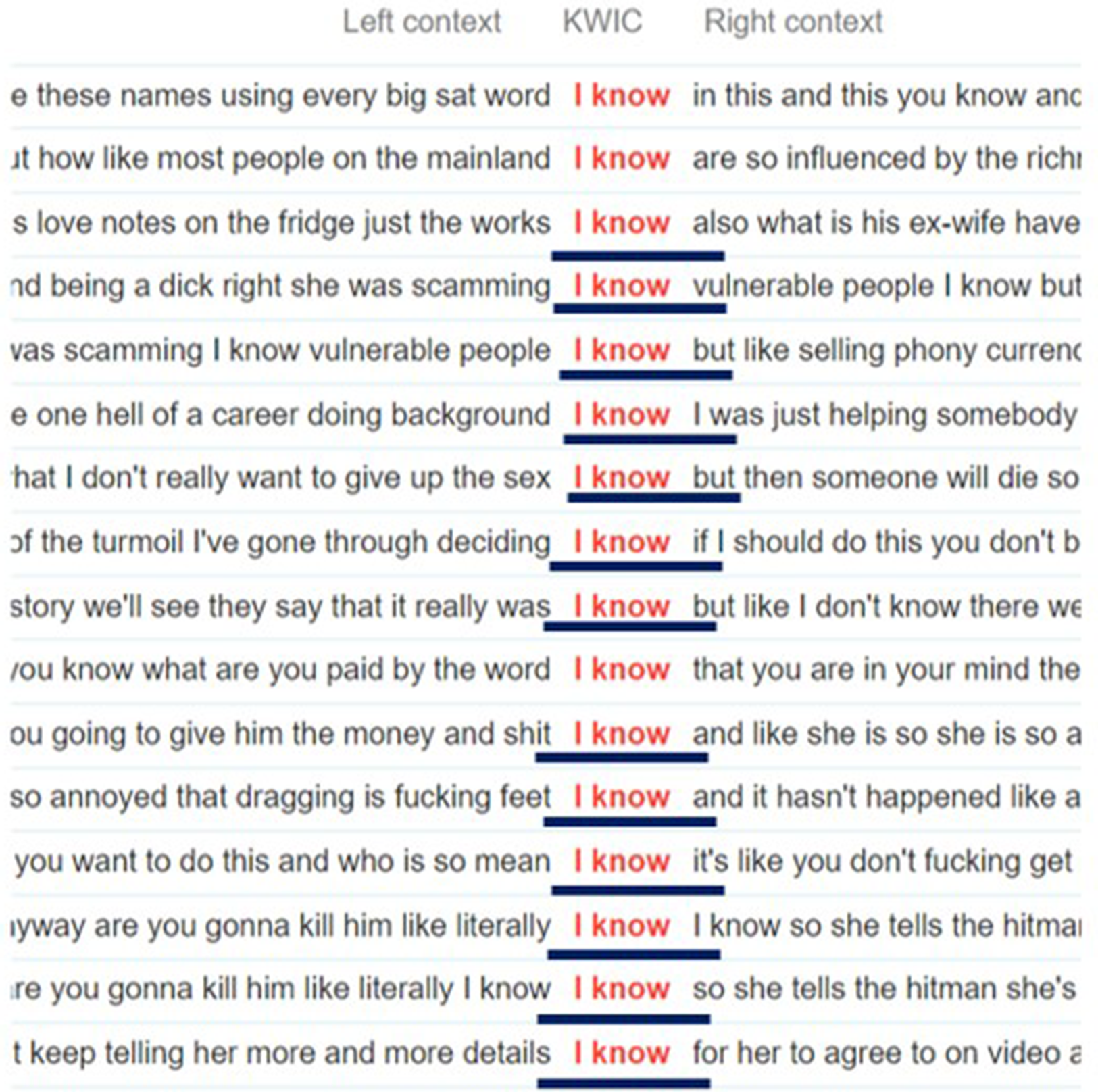

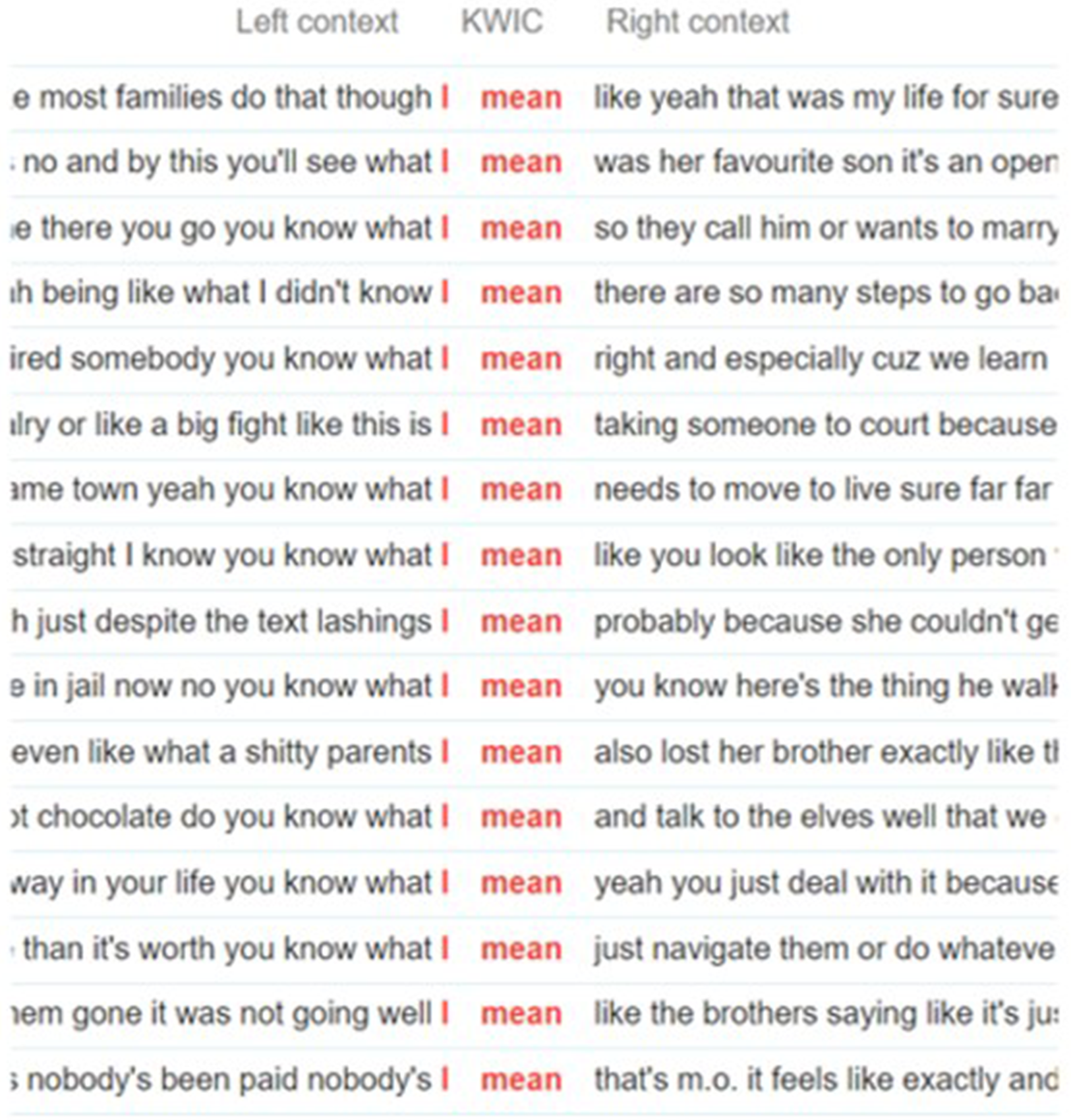

Both you know and I mean, typically used in spontaneous conversations, are often considered on the same level in the category of discourse markers (Fox Tree and Schrock Reference Fox Tree and Schrock2002, 727–728), because of their shared function: typically, you know implies an alignment between speaker and receiver in terms of references and meaning of what is being said, which in this particular case is confirmed by the second speaker who frequently responds with I know (Figures 4 and 5). In general, their function in this corpus, together with I mean (Figure 6), seems to agree with studies that highlight how their frequency in conversation is much higher than other markers (Stubbe and Holmes Reference Stubb and Janet1995, in Fox Tree and Schrock Reference Fox Tree and Schrock2002, 729), and that their use can be related to a specific situation, denoting informality and a fast pace, traits which can be undoubtedly be used to describe True Crime Obsessed.

Figure 4. Examples of “you know” in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

Figure 5. Examples of “I know” as a response (underlined) in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

Figure 6. Examples of “I mean” in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

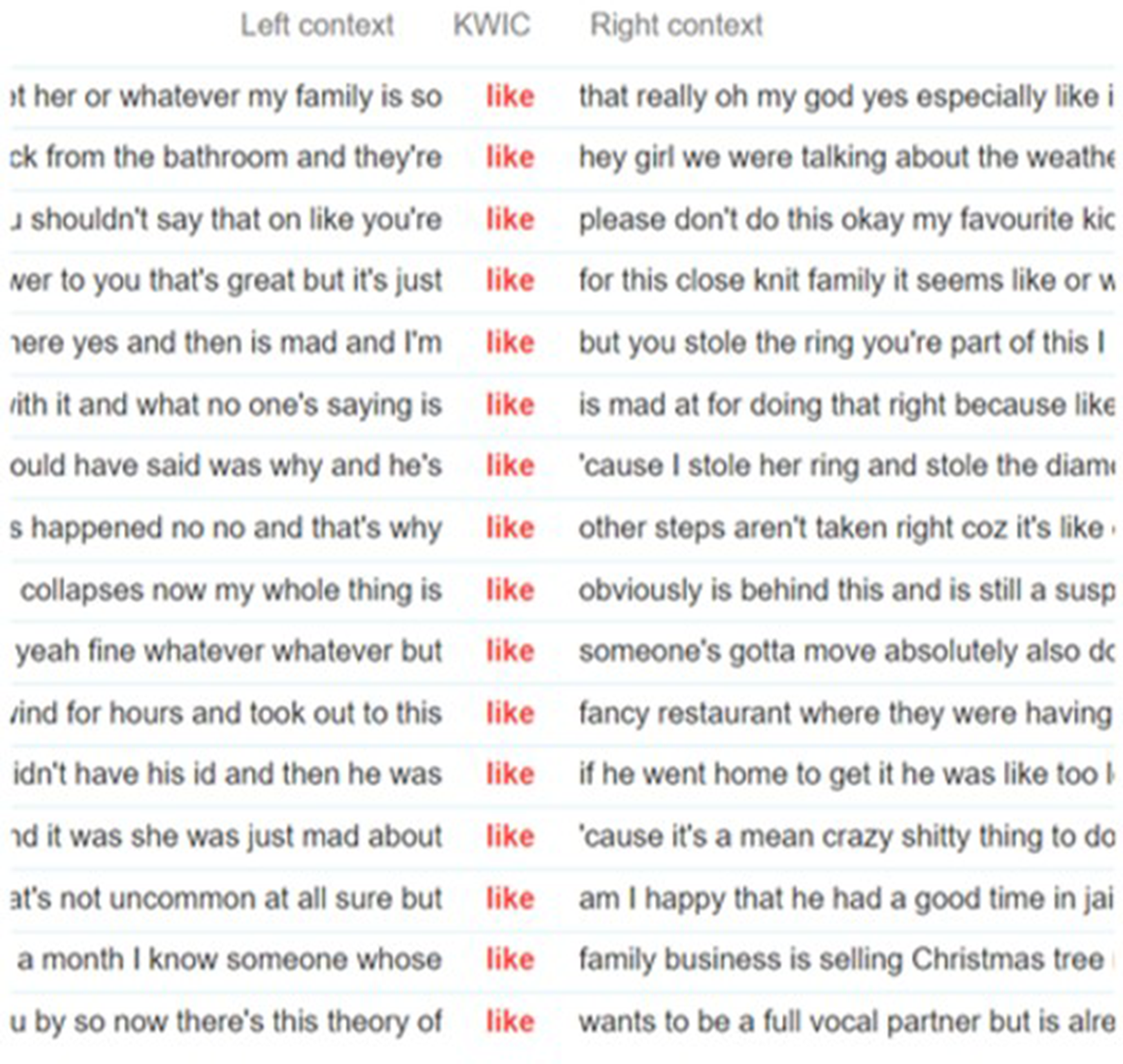

The use of like is mostly to report speech, as shown in Figure 7: it is mainly seen in situations where the speaker is reporting what somebody (or the host themselves) is saying: ‘and I'm, like, but you stole’, and ‘they're, like, hey girl’. Another typical function is to provide the narration with a feeling of the story: ‘this theory of (. . .) like, wants to be a vocal partner’.

Figure 7. Examples of “like” in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

Conversely, the use of right (Figure 8) is mostly to ask for or give confirmation of understanding during the conversation, as turn-taking feature: ‘she's mad at (. . .) for doing that – right – because . . . ’ Finally, one noticeable piece of data is related to the word yeah, which is used throughout so often that it appears as a substantially frequent word in the wordcloud.

Figure 8. Examples of “right” in the TCO corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

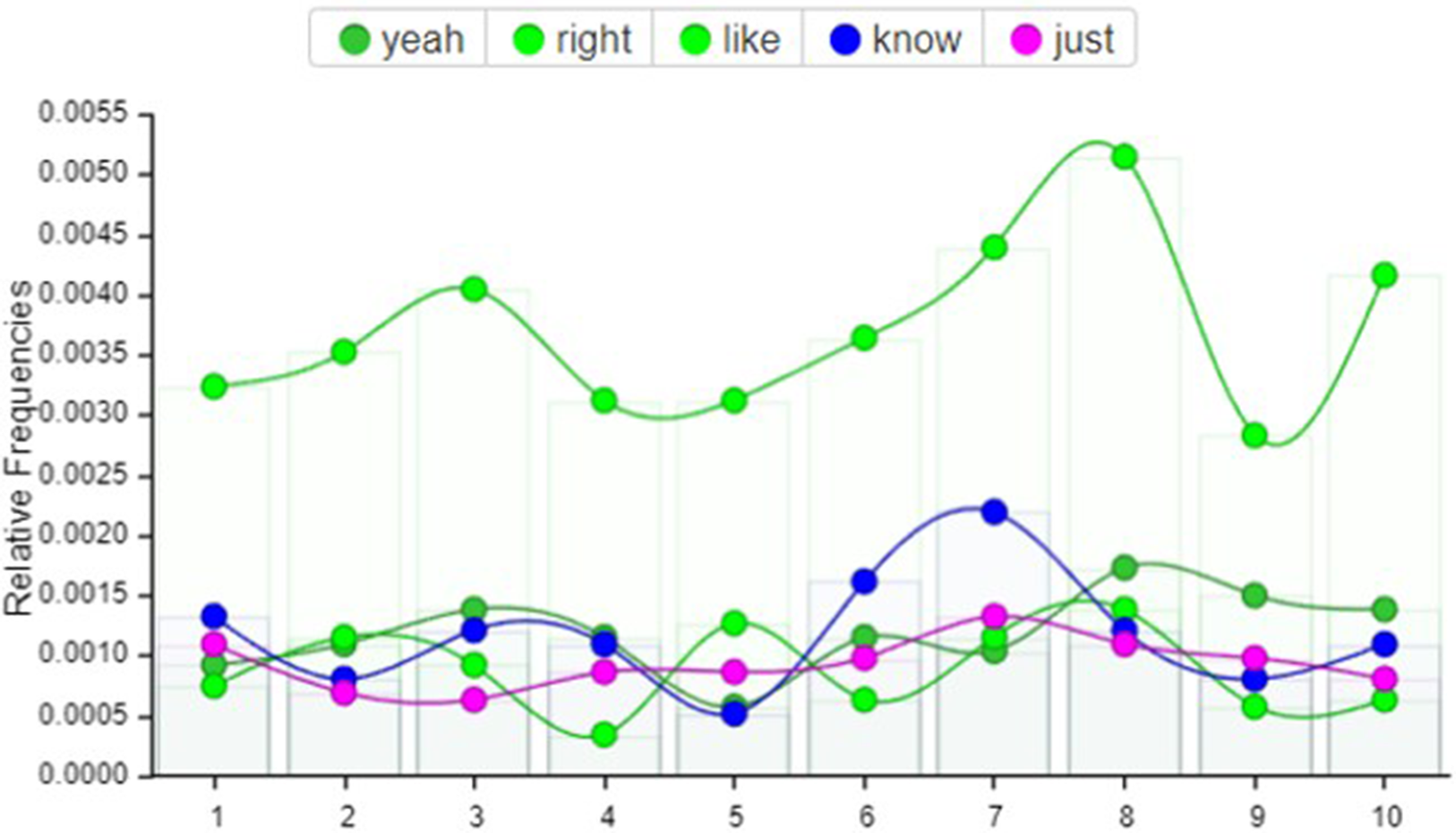

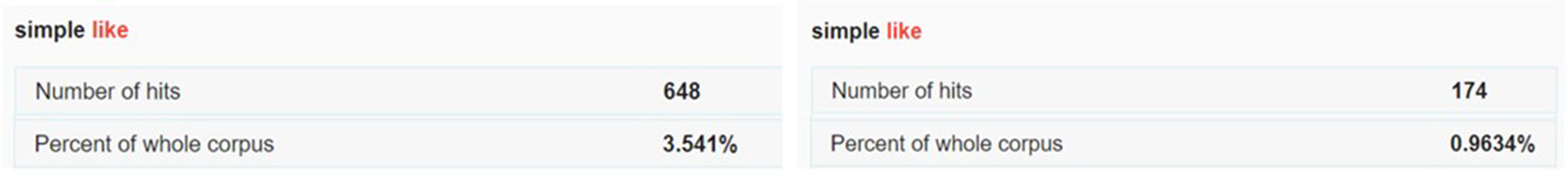

Overall, this corpus proves the high incidence of pragmatic markers in this type of podcast (nearly 7% of the corpus, of which more than half for like – see Figure 12) where the context is moderately informal, and can therefore replicate the typical features of a conversation. True Crime Obsessed, by its own definition a comedy podcast, maintains an informal and colloquial style, and this can justify the higher frequency of markers that would be found in an ordinary conversation (see Figure 9).

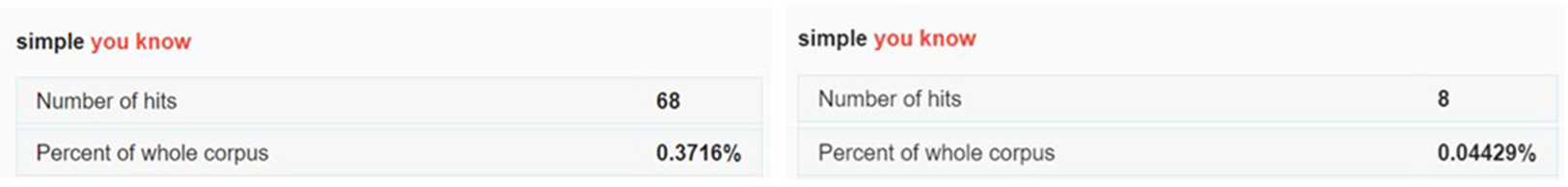

For comparison, another corpus was created from two episodes of a completely different type of podcast, The New York Time Book Review (NYTBR) podcast (NYTCo 2024) (dated from 28th November 2023 and 16th February 2024): here, the episodes are usually conducted by one host in conversation with other book editors or experts in the field of writing and publishing, who are often colleagues from the same newspaper, and therefore the conversation is informal but not to the level of True Crime Obsessed, as it tends to be more business-like and functional (the main function being the presentation, discussion, and comparison of opinions on a book or more). Some useful data for comparison is in the number of pragmatic markers present in this particular corpus: a basic overview of the wordcloud shows that the most common word in the NYTBR is book, which was to be expected, considering the topic of the podcast (Figures 10 and 11), but in terms of pragmatic markers, like is the only one that is repeated often enough to figure in both the wordcloud and in the list of most frequent words (with 174 hits, representing 0.9% of the corpus, as opposed to the TCO corpus with 648 hits, accounting for 3.5% of the total - see Figure 12). The number of markers such as ‘you know’ and ‘I know’ is also significantly lower (0,04% and 0,03 respectively, in contrast to the TCO corpus with 0,3 and 0,4 – see Figures 13 and 14), thus confirming the low level of formality in the TCO corpus.

Figure 9. Trends of the most common words in the TCO corpus.

Figure 10. Worldcloud of the most frequent words in the NYT Book Review corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

Figure 11. Summary of the most frequent words in the NYT Book Review corpus. Created with Voyant Tools.

Figure 12. A comparison of the number of hits for the marker “like” and its percentage in the TCO corpus (left) and the NYT Book Review corpus (right). Generated by the word sketch tool in Sketch Engine.

Figure 13. A comparison of the number of hits for the marker “you know” and its percentage in the TCO corpus (left) and the NYT Book Review (right). Generated by the word sketch tool in Sketch Engine.

Figure 14. A comparison of the number of hits for the marker “I know” and its percentage in the TCO corpus (left) and the NYT Book Review (right). Generated by the word sketch tool in Sketch Engine.

As this is an initial study on the matter, it is however clear that more work and analysis will be required to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to combine the world of true crime podcasts and the world of linguistic analysis: in order to do so, a short analysis was conducted on of the typical pragmatic markers present in two episodes of a long-running podcast, True Crime Obsessed, which provided a small corpus of just over 17,000 words for analysis. The corpus generated a word cloud of a number of highly frequent words, which have been considered in their interaction within the whole discourse, thus showing how, as per the initial hypothesis, the use of markers such as right, you know and like was noticeable as well as predictable for their use in the context of an informal or semi-formal interaction (conversation).

More in-depth studies will potentially show differences in the use of these markers, based on the sub-genre of podcast or even, potentially, by the gender of its hosts. As pragmatic markers and vague language can be varied in their use, either as simple interjections or as means of clarification, rephrasing, agreement, and so on, this topic offers quite a large potential for future research.

CHIARA MARCON is an English language tutor at the University of Trento. She has taught as a language tutor at the University of Manchester and Liverpool John Moores University, as well as several language schools in England, before settling in the north of Italy. She holds an MA in Applied Linguistics and TESOL and another MA in Creative Writing, and one of her main passions is true crime. Email: Chiara.marcon-4@unitn.it

CHIARA MARCON is an English language tutor at the University of Trento. She has taught as a language tutor at the University of Manchester and Liverpool John Moores University, as well as several language schools in England, before settling in the north of Italy. She holds an MA in Applied Linguistics and TESOL and another MA in Creative Writing, and one of her main passions is true crime. Email: Chiara.marcon-4@unitn.it