1. Introduction

On 3 August 2015, a new Facebook page called Kongish Daily was launched in Hong Kong. Its inaugural post parodied English-language media outlets such as South China Morning Post by reporting local news (Kongish Daily 2015). The post describes a Hong Kong man spending HK$400,000 on a marriage proposal, which includes purchasing a diamond ring, reserving a luxurious hotel room and hiring a helicopter to display a ‘Will you marry me’ banner, accompanied by a video production team featuring colourful expressions as below:

Victor gor, a (ho chi ho) rich gei Kong man, spend jor dai la la HKD 400,000 to ask his BB marry him bcoz his BB like ‘something exciting, amazing and not traditional like proposing in a restaurant with flower and a ring’ say Victor gor.

Even ng eat ng play, a Kong guy yiu spend 30 month sin yau almost HKD 400,000. Just think think how impossible for most Kong guy, how many Kong girl will wait a Kong guy 30 months?

Victor gor, I am just a poor guy, so you win!

A native speaker of English would quickly notice that certain expressions in the post are not written in standard English and may only partially comprehend the non-standard usages. For example, ‘Kong man’ refers to a Hong Kong man, while ‘BB’ means babe. Other Cantonese-influenced expressions such as ‘ho chi ho’ (appears to be), ‘ge’ or ‘gei’ (Cantonese particle), ‘dai la la’ (what an enormous amount) and ‘ng eat ng play’ (without food and leisure) would likely be difficult for native English speakers to decode. Additionally, wordplay such as ‘poor guy’ can be interpreted literally or understood as a bilingual pun, as ‘poor guy’ is a homophone for puk gaai 仆街 ‘drop dead’, a Cantonese curse.

The post garnered over 10,000 likes overnight and the Facebook page quickly gained popularity in Hong Kong, with subscribers reaching 40,000 within three months and approximately 76,000 at present. What makes this page unique is its extensive use of localised forms of English, termed Kongish by the editors of Kongish Daily, in news posts and reader interactions, as well as in the exchange of opinions and criticisms among readers. The page has been described as ‘Hong Kong’s hottest new Facebook page’, attracting ‘young, hip Cantonese speaker[s]’ (Yu Reference Priscilla2015). As noted by the Straits Times, the use of Kongish ‘speaks to hearts of Hong Kongers’ (Li Reference Xueying2015). Capitalising on its popularity, the three editors of Kongish Daily, Nick Wong, Alfred Tsang and Pedro Lok, co-authored their first book, Kongish Daily: Laugh L Die (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Tsang and Lok2017), which debuted at the 2017 Hong Kong Book Fair. The book was published by Siu Ming Creation, a sub-line of Mingpao Publications which is well regarded in the Sinophone communities, especially Mingpao Daily founded by the late martial arts novelist Louis Cha (pseudonym Jin Yong). The authors were subsequently named Featured Writers for the Year and invited to participate in book talks and signing events.

The Kongish phenomenon has attracted considerable attention in the field of Sociolinguistics, particularly among scholars studying World Englishes and (Post-)Multilingualism. Much of the discussion focuses on how Kongish contributes to understanding the ongoing development of English in Hong Kong, especially in the post-1997 era. While English remains vibrant in the city, the self-identity of young Hong Kongers is in the process of transforming. As a consequence, local and colloquial registers of English are likely to be increasingly accepted by a broader population of Hong Kongers, particularly among the younger generations.

2. Literature review

Since Kingsley Bolton researched into Hong Kong English (HKE) and its historical-cultural links to English in South China (Chinese Pidgin English) and early Hong Kong (Bolton Reference Bolton2000, Reference Bolton2006), there has existed a paradigm shift in the study of ‘English in Hong Kong’ (Luke and Richards Reference Luke and Richards1982) to a legitimate L2 variety of English under Kachru’s (Reference Kachru1986) World Englishes framework, to which scholars have devoted much efforts in writing linguistic descriptions for HKE on aspects of phonology (Hung Reference Hung2000; Deterding et al. Reference Deterding, Wong and Kirkpatrick2008), grammar (Gisborne Reference Gisborne2000; Setter et al. Reference Setter, Wong and Chan2010), lexis (Wong Reference Wong2009; Cummings and Wolf Reference Cummings and Wolf2011) and pragmatics (Wong Reference Wong2010). Attitudes towards HKE have also become a major focus of scholarly discussion (Chan Reference Chan2013; Hansen Edwards Reference Edwards and Jette2015, Reference Edwards and Jette2016; Ladegaard and Chan Reference Ladegaard and Chan2023), often referencing Schneider’s (Reference Schneider2007) Dynamic Model.

When the Kongish phenomenon emerged in 2015, Kongish was initially categorised under the rubric of HKE. For instance, Hansen Edwards (Reference Edwards and Jette2016) views the establishment of Kongish Daily as evidence of HKE’s increasing acceptance in Hong Kong, implicitly conflating Kongish and HKE. Wong (Reference Wong2017) conceives Kongish as ‘a new type of basilect HKE [which] has been generally accepted by at least the subscribers of a Hong Kong-based Facebook page, Kongish Daily’ (162–163), and as a local norm contributing to ‘a newly emerging, nativised variety of English’ (163).

Sewell and Chan (Reference Sewell and Chan2017) explore the distinctions between Kongish and HKE, assessing whether Kongish qualifies as a new variety of English using Mollin’s (Reference Mollin2006) framework. While Kongish is concluded to meet the criteria of form, function and attitudinal recognition, the authors suggest that Kongish can be differentiated from ‘another kind of HKE’ (597) and propose that Kongish represents a fluid mode of communication in the age of late modernity.

In their seminal paper, Li Wei and the three editors of Kongish Daily conceptualise Kongish as something that ‘defies a neat and simple definition; it is not a thing-in-itself’ (Li et al. Reference Wei, Tsang, Wong and Lok2020, 312). This idea presents an alternative viewpoint, suggesting that Kongish should not be viewed as a subset or (sub-)variety of HKE. Instead, Kongish represents a complex languaging process characterised by creativity and playfulness, which can be classified as translanguaging in action. In this context, Kongish shares similarities with New Chinglish, a form of creative coinage produced by mainland Chinese netizens, examples of which include ‘foulsball’ (foul + football, referring to Chinese football), ‘don’t train’ (deliberate mistransliteration of the Chinese term for high-speed train), ‘sexcretary’ (sex + secretary), etc. (Li Reference Wei2016). Compared to New Chinglish, Kongish is significantly more sophisticated, as the creators and subscribers of Kongish Daily recognise that ‘Kongish is not Chinese nor Hong Kong Chinese, nor is it English nor Hong Kong English, nor is it China English nor New Chinglish’ (Li et al. Reference Wei, Tsang, Wong and Lok2020, 315–316). This characterisation, ‘a-bit-of-everything yet not-a-thing-in-itself’, is seemingly contradictory and highlights complexities that are difficult to address through the traditional variety approach, which typically relies on pattern-seeking and the one-language-at-a-time assumption. Lee (Reference Lee2023, Reference Lee2024) further develops this argument by emphasizing the semiotic aspects of Kongish, suggesting that it can be viewed as an urban dialect on social media and as commodified text-based artefacts.

Such kind of performativity and creativity was referred to as bilinguals’ creativity by Kachru (Reference Kachru1985), where individual bilinguals can enact ‘the use of verbal strategies in which subtle linguistic adjustments are made for psychological, sociological, and attitudinal reasons’ (20). Despite the fuzziness and controversies surrounding Kongish and HKE, one could argue that both should be regarded as local forms of English that have been shaped by the accelerating sociocultural tensions in the city. Hansen Edwards’ (Reference Edwards and Jette2015, Reference Edwards and Jette2016) large-scale before-and-after-study investigating university students’ attitudes and recognition of HKE remains a significant contribution, conducted against the backdrop of sociocultural disputes in Hong Kong culminating in accelerated tension in the mid-2010s. Hansen Edwards (Reference Edwards and Jette2016) documents a strengthening Hong Kong identity and a broader acceptance of HKE’s status with the intensification of these disputes and tensions. Given that nine years have passed since Hansen Edwards published her seminal papers (Reference Edwards and Jette2015, Reference Edwards and Jette2016), a period during which Kongish has flourished and gained notable acceptance on Hong Kong’s social media, this study aims to fill the conceptual gap of this timeframe. We thus pose the following research questions:

1. How does Kongish represent Hong Kong identity?

2. What is the relationship between Kongish and Hong Kong (popular) culture?

3. How do Hong Kongers perceive the future of Kongish?

3. Data and methodology

From November 2022 to February 2023, an online questionnaire was compiled and distributed to gather perceptions of Kongish users. It is important to note the first author’s role as an administrator of the Facebook page Kongish Daily, where he has actively contributed by writing posts, observing reader interactions and responding to comments since its inception. This role provides valuable insights into the social media landscape, allowing him to identify the most relevant information to collect (what), the best methods for obtaining it (how), and the appropriate audience to target (who) as the key actor of the research site (Paltridge and Phakiti Reference Paltridge and Phakiti2015). To promote the study and encourage participation, the first author created several posts on Kongish Daily. The questionnaire was then disseminated through this well known Facebook page dedicated to Kongish writing in Hong Kong. Most supporters and users of Kongish in the city are familiar with and often subscribe to this page. Therefore, Kongish Daily serves as an online community of practice for Kongish users, enabling them to interact and express themselves freely in Kongish. Additionally, students from the university where the first author is employed were invited to complete the questionnaire. In total, we collected 323 responses, providing a quantitative sample size comparable to Hansen Edwards’s (Reference Edwards and Jette2015, Reference Edwards and Jette2016) HKE survey conducted in 2014 (n=307) and 2015 (n=292). From these responses, we selected interesting cases for further analysis.

We acknowledge the time elapsed since Hansen Edwards’s (Reference Edwards and Jette2016) most recent study and the generational shift that has occurred. Recognising the importance of including younger age group in this research, specifically Generation Z, our goal is to accurately reflect how Kongish is perceived and used in the current sociolinguistic landscape in 2020s Hong Kong. To achieve this, we invited a girls’ school in Kowloon to participate in the questionnaire, facilitated by the school’s English Language panel chairperson. The choice was based on the widespread assumption that Kongish is more favoured by young females than males, and that users from elite girls’ schools significantly contribute to the Kongish population (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Tsang and Lok2017, 73–74).

From the questionnaire responses, we selected one senior secondary girl (Form 6) and one junior secondary girl (Form 2) for interviews. We employed snowball sampling techniques, asking these participants to recommend male friends who are active Kongish users and might be interested in participating in the research. After screening, two senior secondary boys (both Form 6) were included in the interviews. The girls and boys represent younger voices in the Kongish community.

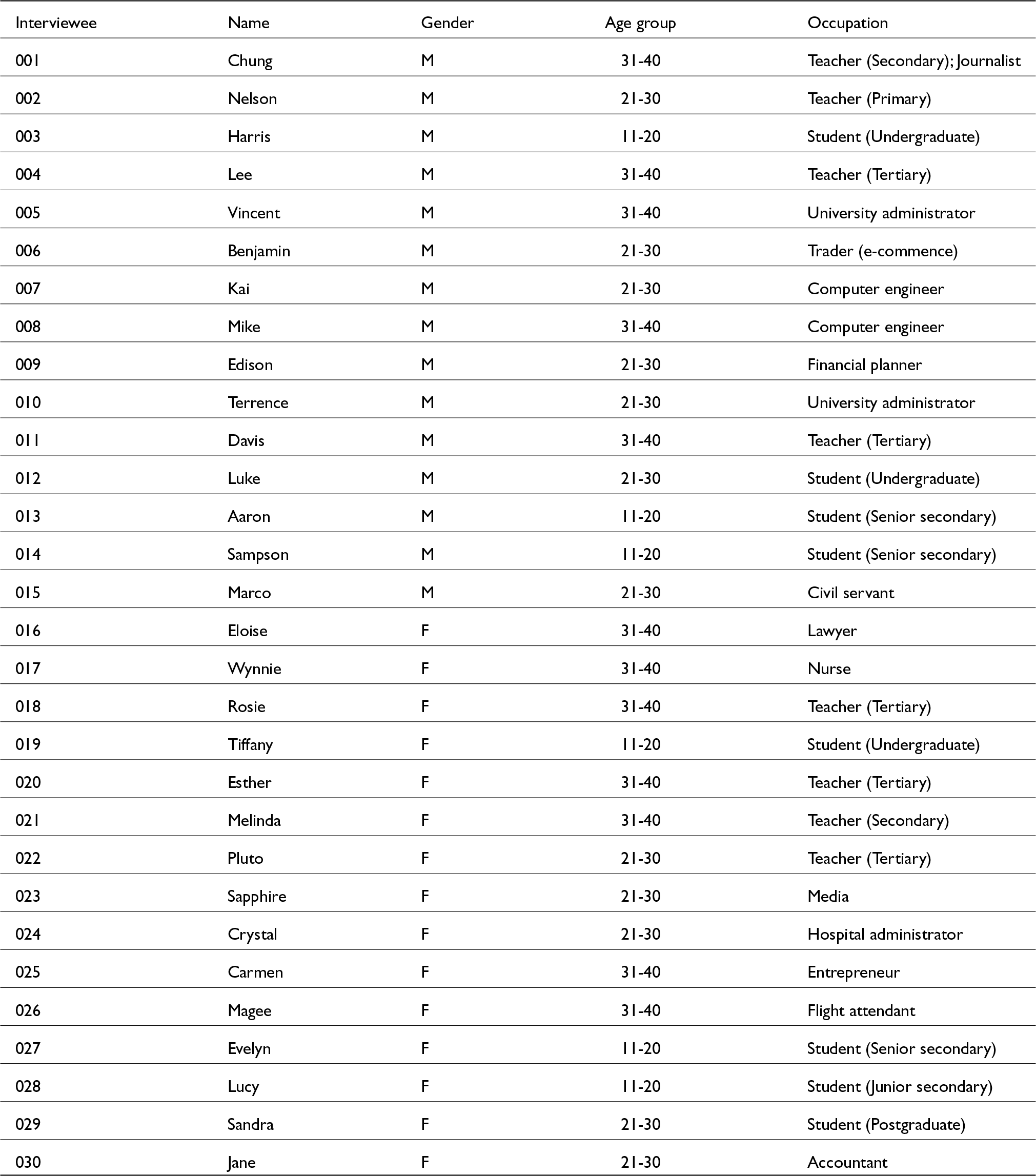

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in July and August 2023. A total of 30 participants, equally distributed by gender (15 males and 15 females), and spanning a wide range of age groups (n[11–20]=6; n[21–30]=12; n[31–40]=12) participated in the interviews. Participants came from various professions: media, computer engineering, aviation, law, healthcare, education, journalism and entrepreneurship. Participants indicated their preferred mode of interview. Most were conducted via Zoom; however, one participant opted for a telephone interview due to concerns about cyber surveillance, and six participants chose in-person interviews at the first author’s workplace. Most interviews were conducted in English, except for three participants who requested to respond in Cantonese or in a mix of Cantonese and English. The interviews were then transcribed, translated where appropriate, and thematically analysed.

Table 1. Demographic data of our participants (n=30) in the semi-structured interview in terms of gender, age and occupation

When analysing the data, we adopt ‘Hong Kong Studies as Method’ proposed by Chu (Reference Chu2016), in conjunction with Asia as Method (Chen Reference Chen2010). This approach emphasizes the tradition of ‘thick description’ in anthropology and sociology (Geertz Reference Geertz1973) and the full use of the steadily available, extensive literature relevant to Hong Kong, particularly works written in the local language. In crafting our narrative, we extend ‘Hong Kong Studies as Method’ to draw knowledge and experiences from local perspectives, challenging the hegemony of English-language discourse. It does not only decolonise the study of sociolinguistics in Hong Kong (see Barnawi & R’boul [Reference Barnawi and R’boul2023] for discussions on coloniality and hermeneutical injustice in the Global South) but also provides a critical lens for examining Hong Kong’s authenticity and avoiding the othering of its culture.

Theme 1: Representing Hong Kong identity

One of the major themes in Hansen Edwards’s (Reference Edwards and Jette2016) study concerns the role of cultural identity in Hong Kongers’ perception of the legitimacy of HKE. Hansen Edwards reported a strengthening sense of identity among Hong Kongers after 2014, with the majority (88.33%) identifying themselves as Hong Kongers, and only 11.66% identified as Hong Kong Chinese or Chinese. She predicted that ‘if speakers of English in Hong Kong continue to embrace a local Hong Kong identity, acceptance of HKE, as a marker of this identity, will also probably increase’ (163).

Following this line of thought, one could postulate that the social climate after 2014 would facilitate the increased endorsement of HKE in general, and Kongish in particular, as citizens view it as a symbol of their identity. Of the 30 participants we interviewed, nearly all (n=28) expressed strong certainty that Kongish represents Hong Kong identity. The most prominent reasons included statements such as, ‘This is how we Hong Kongers communicate on social media.’ (Edison, male, 21–30); ‘Once reading posts of this kind, I can immediately tell the writer must also be from Hong Kong’ (Sapphire, female, 21–30); ‘No matter where you are in now, as long as you are a Hong Konger and you speak Cantonese and English, you automatically write in this way without any training’ (Carmen, female, 31–40). These comments suggest that Kongish is recognised by Hong Kongers as a mode of communication that fosters a clear sense of in-group identity.

This in-group identity can be positively perceived as in-group solidarity, similar to other vernacular Englishes such as Singlish (Cavallaro and Ng Reference Cavallaro and Ng2009). Magee describes her psychological state when reading Kongish: ‘I feel warm; I have a me-sense when reading posts written in Kongish. I feel like someone is whispering in my ear, though in reality, we don’t really read Kongish loud. We speak English or Cantonese’ (Magee, female, 31-40). Magee highlights a similarity between Kongish and vernacular Cantonese, noting that both languages are constrained by the written/spoken distinction and do not fully function in both domains. Traditionally, Cantonese is used for speech, while most people switch to Standard Chinese for writing, despite the evolving landscape of written Cantonese in recent years (Snow Reference Snow2004; Bauer Reference Bauer2018). In contrast, Kongish as a performative variety (Sewell and Chan Reference Sewell and Chan2017) relies heavily on digital platforms and is primarily used in written form.

Some participants (n=6) mentioned the exclusion of out-group members, stating, ‘Only people from Hong Kong can understand Kongish; people outside may not grasp our language and the culture, including the humour. For example, JM9ʹ (Tiffany, female, 11–20). This exclusion allows users to humorously express discontent without touching sensitive cultural nerves: ‘Sometimes we talk about sensitive topics … writing in Kongish seems soft and subtle. We can tone down expressions which may cause trouble in Chinese, for example, Strongese referring to arrogant tourists from mainland China who initiate conflicts on Xiaohongshu. I worry about being accused of discrimination if I write formally in Chinese, although Strongese to me is just a humorous expression of my discontent with the current situation, just like Gwailo for foreigners. Actually milder’ (Marco, male, 21–30).

Marco’s commentary is insightful in relation to the potential of Kongish to create in-group/out-group distinctions and to express stances in an indirect manner (Li and Lee Reference Wei and Lee2021; Wong and Garcia Reference Wong and García2025; Lok et al. Reference Lok, Lee, Tsang and Wei2025). Hence, in times of heightened sociocultural tensions, social media users in Hong Kong often resorted to their translanguaging instinct to circumvent standard Cantonese romanisation schemes and adopted an ad hoc, idiosyncratic way of encrypting messages. Thus, ‘in-group’ messages such as ‘818, Wai Yuen Gin! (See you in Victoria Park on 18 August!)’ (Wong Reference Wong2024, 169; Lok Reference Lok2024, 53) and ‘IF YOU waai yi yau GHOST, WRITE ON A PIECE OF PAPER “nei ji m ji ngo kap mat chat a?” (If you suspect there is an undercover, write this on a piece of paper “Do you know what the hell I am talking about?”)’ (Li and Lee Reference Wei and Lee2021, 139) would prove impenetrable to ‘out-group’ persons who are not conversant in this hybrid Cantonese-English register. Davis (male, 31–40), a teacher by profession, confirms this: ‘For those who are not from Hong Kong, even if they study or live here for several years, no matter how well they speak English or Mandarin, and regardless of how much they can earn, they still won’t fully grasp Kongish, the everyday language of us Hong Kongers.’ While Davis’s comment may initially sound cynical, it carries a few important implications: 1. Kongish serves as an identity badge of Hong Kongers; 2. Even outsiders who study or work in Hong Kong for years may not understand Kongish; 3. Proficiencies in English and Mandarin, though traditionally considered High varieties (Fasold Reference Fasold1984), do not necessarily guarantee successful communication in Hong Kong; 4. There also implies a subversive view on the existing social hierarchy, i.e. mastering English is a sign of the socioeconomically privileged which can yield handsome income, yet possessing such privilege does not allow one to access Kongish, ‘the everyday language of us Hong Kongers’, indexing the linguistic and cultural subjectivity of Hong Kong; 5. Kongish is intrinsic to the daily lives of Hong Kongers. In summary, Kongish is closely tied to Hong Kongers’ identity and life experiences.

While most participants agree that Kongish reflects Hong Kong identity, two expressed reservations: ‘I would say it represents Hong Kong identity to some extent, no doubt. But I’m not sure if it is equal to Hong Kong identity, as there are people who don’t speak English in Hong Kong, not to say using Kongish’ (Pluto, female, 21–30); and ‘My grandparents don’t speak Kongish or English; is it fair to say they are not Hong Kong people? Many older people of their generation only speak Cantonese or other Chinese dialects like Hakka’ (Terrance, male, 21–30). It is therefore reasonable to conclude that young Hong Kongers accept that Kongish can represent Hong Kong identity while also recognising that multilingualism profiles of Hong Kongers vary across generations. Hong Kong identity encompasses a range of linguistic profiles, particularly applicable to Generations Y and Z.

Kai (male, 21-30), a young computer engineer, offers an intriguing perspective on associating Hong Kong identity with his experience of inputting Chinese, English, and Kongish:

The way Hong Kong people type Chinese is actually part of our linguistic identity. Mainlanders simply use Pinyin to input simplified characters, while Taiwanese use Cangjie or Bopomofo to input traditional characters. In this regard, Hong Kongers are similar to Taiwanese, but still different […] When typing English, very few people use serious English. We usually type in Cantonese romanisation with Chinese grammar […] This is practised in Hong Kong, not mainland China or Taiwan. I reckon it isn’t popular in Macau either.

The challenges of inputting Chinese characters are suggested to motivate Hong Kongers to use Kongish creatively (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Tsang and Lok2017; Li Wei et al. Reference Wei, Tsang, Wong and Lok2020). Compared to other Sinophone communities, Hong Kongers have had painful experience of inputting Chinese characters. Most Hong Kongers opt for traditional Chinese operating platforms (OS), e.g. Microsoft Windows, which were developed for Taiwanese users and come with Cangjie, Quick and/or Bopomofo pre-installed. Very few choose simplified Chinese OS with Pinyin as the input method. However, the linguistic differences between Hong Kongers and Taiwanese lead to input challenges, where Hong Kongers speak and type Cantonese, yet Cangjie, which is based on Mandarin or Standard Written Chinese, does not accommodate vernacular characters frequently used in Hong Kong, e.g. 啲 (di1, literally ‘some’) (Cheung and Bauer Reference Cheung and Bauer2002). The complexity of learning Cangjie has discouraged many Hong Kongers from typing Chinese and has led Cantonese-English bilingual Generation Y to use codemixed English, the precursor to Kongish. Kai reminds us that the technological experiences can evoke a sense of linguistic identity.

Theme 2: Kongish and (popular) culture

In Hansen Edwards’s (Reference Edwards and Jette2015) study, a noticeable portion of respondents agreed that HKE could ‘represent Hong Kong culture’ (194) or was ‘unique to Hong Kong culture’ (203). Linked to Theme 1, young generations desire a distinctive cultural identity as Hong Kongers and favour local languages such as Kongish. We can further this argument by asserting that Hong Kong’s younger generations also embrace popular culture, as evidenced by the revival of Cantopop in recent years (Chu Reference Chu2019), a time when it is felt that the cultural identity of Hong Kong people needs to be strengthened.

In our semi-structured interviews, participants were asked whether they agree that Kongish can represent Hong Kong’s culture, immediately following questions about identity. As expected, the response was overwhelmingly positive, with all participants (n=30) agreeing or strongly agreeing that Kongish is part of the city’s culture: ‘Of course, Kongish is definitely Hong Kong culture. The name Kongish makes it clear. It’s not Chinglish, not Singlish, but Kongish, doesn’t it?’ (Crystal, female, 21–30); ‘Yes, my schoolmates and friends all use Kongish, and everyone understands it!’ (Tiffany, female, 11–20); ‘In our workplace, only colleagues or supervisors who are Hong Kongers, or clients who appear nice to us, use Kongish in socialising. It’s clearly part of Hong Kong culture’ (Jane, female, 20–30).

Benjamin (male, 20–29), a trader, shared his experience of purchasing a Kongish t-shirt, highlighting Kongish as a cultural product: ‘I remember Kongish Daily had a joint venture with a local manufacturer from the Mills and sold seasonal products like t-shirts before Covid-19. I bought one with SOR9LY on it! Kongish is really cool. It is an icon of popular culture.’ Benjamin’s description of Kongish as ‘an icon of popular culture’ in contemporary Hong Kong aligns with views from both the public and scholars, who regard Kongish as a form of popular culture, an expression from below, a basilectal HKE variety, or an urban dialect that fits within the realm of mass culture (Adorno and Bernstein Reference Adorno and Bernstein2020).

Wee (Reference Wee2023) recently introduced the concept of MK Lingo, arguing that Kongish should be examined within the broader context of the Mongkok (MK) culture. According to Wee, MK culture signifies ‘roughly the urban street culture that identifies with the geographical areas covering Kowloon’s Yau Tsim Mong district (which includes Yau Ma Tei, Mongkok, and Tsim Sha Tsui)’ (422), characterised by traits such as ‘a certain sloppiness in dress code, one enhanced by accessories, dyed hair (usually gold), humorous uses of vulgarity, creative linguistic expressions that become slang, and a general sense of rebelliousness’ (422) rather than geographical experiences such as walking through or living in such districts. Wee argues that many linguistic expressions ‘exemplified as Kongish can be sourced from such MK online agora as Lihkg.com (launched in 2016) that grew out of hkgolden.com (established in the early 2000s, thus clearly precedent)’ (422). Indeed, MK culture is considered an important aspect of Hong Kong’s popular culture and is often discussed in the studies of Hong Kong culture (c.f. Soengsyuguk tungjan 2010, 56–57) and adopted in vernacular literary creation, such as in An Otaku Changed by an MK Girl (Wong Reference Wong2017).

While it may not be difficult for those familiar with Kongish and other Hong Kong languages (e.g. Cantonese) to trace the etymology of certain Kongish words and phrases back to their use on LIHKG or hkgolden.com prior to Kongish Daily, one could counter Wee’s (Reference Wee2023) assertation that LIHKG, hkgolden.com and Kongish belong to the same ‘MK online agora’. A discussion thread initiated by a LIHKG member Sitoubatdou (Stubbs Road), titled ‘Pick One from the Two: MK Guy or LIHKG Guy?’, invites other members to vote on a scenario in which a girl were to choose between an MK guy and a LIHKG guy as her boyfriend (Sitoubatdou 2023). The discourse suggests that LIHKG members distinguish themselves from MK guys and perceieve LIHKG and MK as two separate social groups, despite both communities sharing ‘humorous uses of vulgarity, creative linguistic expressions that become slang, and a general sense of rebelliousness’ (Wee Reference Wee2023, 422). From the translanguaging perspective, Kongish users tap on their full range of semiotic repertoire in communication and creation, which would unsurprisingly encompass calques, idioms and other phrases sourced from LIHKG or evolved from hkgolden.com.

During the interviews, we posed another question to participants: ‘Do you think that Kongish is a kind of MK culture?’. Most participants (n=29) deny that Kongish and MK culture are equivalent. Participants expressed a strong belief in the correlation between English proficiency and social class:

I don’t think this is a fair statement. I don’t think MK jai (Mongkok guy) is capable of using Kongish. They don’t even have a strong English background. They may understand a few English words, maybe very simple words like sor9ly, exact7ly and laugh die me. But I don’t see they have the ability to play around in between the two languages. They may do wordplay in Cantonese rather than Kongish (Melinda, female, 31–40)

Melinda is an English teacher at a traditional girls’ school in Hong Kong with over 15 years of ESL teaching experience. Her view is echoed by other participants: ‘People from MK don’t receive good education’ (Sampson, male, 11–20); ‘Except for a few, I think most MK people are not able to use Kongish’ (Luke, male, 21–30); ‘Most MK people are just secondary school dropouts or public exam losers. They perform extremely poorly academically and can’t speak English well’ (Eloise, female, 31–40); ‘When I started as an IVE (vocational institute) student, many used Cantonese with some Martian expressions and a few English words in the chat, and they added English words quite pretentiously. But later, when I progressed to this university, I found most girls just used Kongish in typing, but the feeling is much different. It’s just casual’ (Harris, male, 11–20). Before one can effectively use Kongish, they must be reasonably proficient in both English and Cantonese. As espoused in the ELT research, children from Hong Kong’s middle-class families receive better educational resources than their grassroots peers in ESL or EFL learning (Leung and Li Reference Leung and Li2017; Li Reference David2017). MK individuals embracing MK culture are often regarded as being outside the mainstream, although some may attempt to create a sense of respectability through limited use of English in the conversation, as discussed in studies on Hong Kong’s cultural-linguistic phenomena, such as Fake-ABC accent (Jenks and Lee Reference Jenks and Lee2021), JM tone (Chau Reference Chau2021) and Kong girl speech (Chen and Kang Reference Chen and Kang2015; Chau Reference Chau2021; Wetters Reference Wetters2021).

As aforementioned, Wee (Reference Wee2023) attempts to define the characteristics of MK culture, visualised through accessories, hairstyles, and the use of vulgar, humorous and creative language. Lee (male, 31–40), currently an EAP lecturer, who describes himself old enough to witness the changes in the city, provides a critical perspective on the matter:

First of all, does MK culture still exist? I don’t think it does in the recent 10 years. It was a very old-school thing. When I was a teenager, there was MK culture. But nobody talks about that now. Mongkok is quite gentrifying, so as a lot of places in Hong Kong. I don’t know many very Mongkok people, I can’t tell much. But It seems like quite a different phenomenon, and one does not necessarily look like the other.

Lee questions the essence of MK culture and doubts its existence today. As gentrification becomes the new norm in Hong Kong, impoverished urban areas such as Mongkok and Sham Shui Po are undergoing processes of urban redevelopment (La Grange and Pretorius Reference La Grange and Pretorius2016; Tang Reference Tang2017). Old-day symbols, including MK figures and culture, tungdong (youth gangsters), guwaakzai (members of triad societies) and others, are fading from the consciousness of Hong Kongers. These symbols, once prominent in Hong Kong film productions of the 1990s and early 2000s, have become increasingly rare over the past decade.

If Lee’s assertion regarding the disappearance of Mongkok culture is accurate, new generations will miss the opportunities to experience the vernacular culture that was once familiar to every Hong Konger. Indeed, when the same question was posed to Lucy, a 13-year-old Form 2 student, her answer serves as evidence supporting the validity of Lee’s argument: ‘To say it is MK culture is like saying that the users are from somewhere in Hong Kong. But I think not only people from Mongkok would use Kongish. Just like in my school, everyone uses it, but they do not live in Mongkok’ (Lucy, female, 11–20). Lucy interprets the term ‘MK culture’ in its literal sense, viewing it as the culture observable in the Mongkok district or among its residents. This interpretation is clearly misguided.

Theme 3: Future of Kongish

Hansen Edwards (Reference Edwards and Jette2015; Reference Edwards and Jette2016) documented the growing recognition of HKE as a legitimate variety of English and an increasing number of respondents declaring that they speak HKE. She predicted that HKE would ‘gain acceptance among a wider population of speakers of English in Hong Kong’ (164). Since the mid-2010s, HKE has been embraced by an even larger number of English speakers in Hong Kong, as evidenced by the success of Kongish Daily and other forms of literary creation, e.g. Louise Leung, a Generation Z Hong Kong poet proclaiming herself to ‘give voice to Hong Kong’s localism through Kongish literature’ (Leung Reference Leungn.d.).

To evaluate Kongish users’ perspectives on its future, we asked our participants, ‘What do you think about the future of Kongish?’. We encouraged them to envision how Kongish might develop over the next one to two decades. About two-thirds of participants (n=19) expressed optimism about the future, commenting, ‘The future of Kongish is obviously bright’ (Terrance, male, 21–30); ‘Now the tradition [of Kongish] has been laid. More and more young people will follow and strengthen this culture’ (Wynne, female, 31-40); ‘People in Hong Kong are more heavily Internet addicted, especially in the use of social media. More or less, Kongish words will be merged into their daily posts or stories on Instagram’ (Jane, female, 21-30); ‘Most people of my age, as well as girls in junior forms, use Kongish in daily communication, despite some new immigrants who speak Putonghua in their own circles’ (Evelyn, female, 11–20).

One participant credited Kongish Daily with playing a crucial role in helping Hong Kongers recognise Kongish by promoting Kongish writings openly and rectifying the negative connotation of Chinglish that had previously been attached to such codemixing practices: ‘Kongish Daily has an important contribution to the development of Kongish. Before it existed, nobody dared to claim that we write in Hong Kong English publicly. People criticised it as Chinglish. So negative, although we often knew it was restricted to informal contexts’ (Magee, female, 31–40). Her perspective aligns with that of the creators of Kongish Daily, who have witnessed significant changes in the 2010s, where the social use and recognition of vernacular languages, including Kongish and Cantonese, rose. The editorial draws an analogy between the current sociolinguistic changes in Hong Kong and those in early 20th-century China, where baihua (vernacular Chinese) replaced wenyan (classical Chinese) as the new norm of writing at the turn of modernity (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Tsang and Lok2017, 149-151).

Among the positive outlooks, it is noteworthy that Kongish is seen as globalising. A significant number of Hong Kongers have left the city to start new lives overseas following successive waves of migration since 2020. The BN(O) Scheme alone accounts for a current migration figure of 184,700 people (Yiu Reference Yiu2024). Chung (male, 31–40) expresses optimism about the opportunities for globalising Kongish: ‘The population migrating to the United Kingdom is large. Now in cities like London and Manchester, you can easily encounter Hong Kongers and our community networks […] I believe Kongish will be firmly rooted in England […] just like Spanish or Spanglish in the United States.’ In other words, Kongish is expanding geographically from Hong Kong to other places, particularly Anglophone destinations such as the UK. It may evolve from a language used for intragroup communication (within Hong Kong) to one used for interethnic communication (e.g., in the UK).

Among the more pessimistic views regarding the future of Kongish, the most frequently cited concern is the threat posed by Putonghua, as enforced by the current medium-of-instruction policy. Terrence (male, 21–30), a university administrator, elaborated: ‘The future of Kongish will depend on the education system in Hong Kong. Our government is trying to use Putonghua instead of Cantonese in Chinese education. More teenagers are speaking Putonghua even outside classrooms. I often hear it on the street and on the train. So maybe in the future, there will be no Kongish anymore. A new mixture of Putonghua and English may emerge with a new name.’ Since Kongish primarily encompasses Cantonese and English, it could be at risk when Cantonese continues to be threatened. Sociolinguistic studies of Hong Kong have documented citizens’ resistance to Putonghua and their defence of Cantonese, highlighting the competition and conflict between these languages at the societal level (Bauer Reference Bauer2016; Wong Reference Wong2021; Wong and Wong Reference Wong and Wong2023). This concern is echoed by Elson, a frontline teacher (male, 21–30): ‘In Hong Kong, we have more and more CMI (Chinese as the medium of instruction) schools. Students are taught in Putonghua rather than in Cantonese […] If they are not familiar with Cantonese and English, it won’t facilitate Kongish.’

Lucy (female, 11–20), a Form 3 student from an EMI school, shares a similar observation regarding the language habits of her juniors: ‘I notice that Form 1 and Form 2 students are starting to use more simplified Chinese when typing on WhatsApp. Maybe they find it more convenient to type pinyin than to learn Kongish. Higher-form students still use a lot of Kongish to communicate, but lower-form students are switching to Putonghua’, indicating new changes are emerging under the influence of Putonghua education. Aaron (male, 11–20), a senior form student, believes that Kongish has already reached its peak despite its current prevalence. He expresses skepticism about the future development of Kongish, stating that ‘As more and more people are leaving Hong Kong, and an increasing number of mainland Chinese students are coming to study in Hong Kong, the Kongish culture will disappear, much like Cantonese, which will mainly be spoken by older generations. Most will use Mandarin instead.’

Luke (male, 21–30) offers a thought-provoking commentary on the future of Kongish: ‘Kongish might not grow as much actually. The most favourable factor of using Kongish has gone. As the status of Cantonese rises in Hong Kong, people may focus on promoting proper Cantonese and move away from using Kongish. They might think that Kongish is a subset of Cantonese using English alphabets but not Chinese characters to express the meaning, thus not so proper.’ Kongish and Cantonese are often seen as belonging to the same category of being vernacular, informal, and non-standard, yet both represent the identity of culture of Hong Kong people. The two languages are frequently regarded as allies in the face of the hegemony of Putonghua. However, as Luke’s term ‘proper Cantonese’ suggests, Cantonese embodies an authenticity of Chineseness. The fact that Kongish utilises an alphabet-based orthography while adhering to Chinese grammar renders it more non-standard or inferior compared to its Cantonese counterpart. The two allies paradoxically become rivals, competing on the frontline against Putonghua.

4. Conclusion

The present study employs qualitative semi-structured interviews to investigate participants’ views on Kongish in relation to Hong Kongers’ identity and culture, as well as the future prospect of Kongish. We begin with a survey that corroborates Hansen Edwards’s (Reference Edwards and Jette2015; Reference Edwards and Jette2016) findings that attitudes and identity towards HKE have pivoted toward greater acceptance in the mid-2010s. To account for potential generational shifts, we include the voices of Generation Z when recruiting participants for our interviews, ensuring that our data can represent a comprehensive spectrum of Kongish users, including those from the post-1980s, post-1990s and post-2000s cohorts.

To address our research questions:

1. How does Kongish represent Hong Kong identity?

Young Hong Kongers express pride in using Kongish to communicate on social media, and they observe their peer of doing the same. The collective practice of mixing Cantonese and English in typing Kongish reflects their linguistic identity and showcases multilingualism of Hong Kongers, fostering an in-group identity. At times, Kongish users can encode their intended messages, effectively excluding out-group members from understanding them, especially when users are aware of the potential conflicts arising from language use. The challenges of typing Chinese and the adoption of Cantonese-English translanguaging practices (e.g. romanisation of Cantonese words) as a solution create the digital Hong Kong identity, distinguishing Hong Kongers from those in other Sinophone communities.

2. What is the relation between Kongish and Hong Kong (popular) culture?

It is widely accepted that Kongish is an integral part of Hong Kong culture and serves as a cultural symbol. The name Kongish itself signifies a distinct Hong Kong vernacular. Multilingual young generations use Kongish daily, and even in business settings (e.g. small talks), it has been reported that outsiders strategically engage with local colleagues in Kongish, indicating that it is firmly rooted in the city’s culture. Many recognise Kongish as a form of popular culture, as evidenced by its linguistic creativity and the recent popularity of commodified text-based artefacts. The shared playful and sometimes vulgar nature of Kongish, along with elements from other Internet forums, is sometimes associated with MK Lingo, alongside other Mongkok influences such as MK girls. However, it is important to note that most Kongish users do not agree with this characterisation. They possess a clear awareness of the performativity of Kongish; rather than viewing non-standard writing as a sign of English incompetence, most Kongish users understand the bilingual threshold of writing in Kongish.

3. How do Hong Kongers perceive the future of Kongish?

The status of Kongish has been on the rise since the establishment of Kongish Daily, when the editors explored a new way of writing ‘formal genres’ (i.e. news articles) in Kongish, which was previously labelled as Chinglish or gongsik jingman 港式英文 ‘Hong Kong-style English’, literally referring to errors made by English learners in Hong Kong. Kongish has been embraced by the new generations of the city. Most Hong Kongers have positive outlook on its future, given the present status Kongish has achieved, the technological affordances available, and the social media-oriented communication habits of Hong Kong’s multilingual generations. Some see potential for the globalisation of Kongish alongside the ongoing diaspora. However, others express more pessimistic views, as Putonghua has been increasingly reinforced in the teaching curriculum. More Hong Kong teenagers are observed communicating in Putonghua, which facilitates a shift of intergenerational linguistic preferences from Cantonese to Putonghua. This change in the linguistic landscape could hinder the development of Kongish.

As Kongish gained popularity in the 2010s, drawing definitive conclusions about this evolving phenomenon may be premature. One significant aspect of this study is to document the current state of Kongish, specifically its user perception and language identity, while also providing a forward-looking perspective on how Kongish users envision its future and how the young, particularly those from Generation Z, think. This study contributes to the understanding of the changing perceptions of English(es) and languages in 2020s Hong Kong, as well as how Kongish, as a Catnonese-English mixed language practice, reflects citizens’ fluid communication practice and their associated culture and identity.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by a General Research Fund from the Research Grants Council, Hong Kong SAR (Project no: 17603821).

ALFRED TSANG is Lecturer of English at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. His research interests cover sociolinguistics, (post-)multilingualism, Global Englishes, translanguaging, corpus linguistics and English for Academic Purposes. Email: lcalfred@ust.hk

TONG KING LEE is Professor of Language and Communication at the University of Hong Kong and Honorary Professor of Culture, Communication, and Media at University College London. He takes professional and academic interest in a wide range of subjects, including intercultural and nonverbal communication for global business, legal communication, World Englishes, translanguaging, multimodal and digital semiotics, and creative translation. Email: leetk@hku.hk

LI WEI is Chair Professor of Applied Linguistics at University College London. He is Director and Dean of IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society. He holds Fellowships of the British Academy, Academia Europaea, Academy of Social Sciences and Royal Society of Arts. His research centres around different aspects of bilingualism and multilingualism, including the acquisition of multiple languages in childhood, family language policy, education policy and practice regarding bilingual and multilingual learners of minoritized and transnational backgrounds, complementary schools, cognitive benefits of language learning, and impact of on social cognition and creativity. Email: li.wei@ucl.ac.uk