So much has been written about the Parthenon’s Ionic friezeFootnote 1 that one may wonder—indeed, I have received this question—whether there is anything new to say about it. The 160-metre-long, 1-metre-high low-relief carved frieze was designed by PhidiasFootnote 2 and put in place on the Parthenon sometime in the 440s b.c.e. The decision to place an Ionic-style frieze on a Doric building was an unusual oneFootnote 3 and, while evidence may suggest that it may not have been originally intended, its inclusion was worked through the ongoing design and building process.Footnote 4 There are no extant ancient commentaries on the frieze, perhaps owing to the difficulty of seeing the sculptures in place. Scholars broadly agree that the frieze reflects a version of the procession undertaken during one of the penteteric ‘Greater’ Panathenaic festivals, whether an ‘archetype’ of the procession, an early historical or mythic version, or some other iteration of the festival.Footnote 5 The west face—the back of the building—shows horsemen readying for the procession; they travel in both directions from the northwest corner and down the southern face and along the west and up the north faces. From west to east, the long-side faces show a procession of horsemen, chariots, elders, musicians, water-carriers, tray-bearers and sacrificial victims. These should be read as two sides of the same procession. All the participants on these sides are male. The east face shows, mirrored from the outsides to the centre, parthenoi,Footnote 6 a group of men who are routinely identified as the eponymous heroes or magistrates as identified by their dress,Footnote 7 two groups of seated gods, while in the centre, above the doorway to the naos, is the peplos scene.Footnote 8

In this article, I will explore two small sections of the east face of the frieze, where the two sections of gods meet the procession coming from either side of the building. I will first briefly consider the time-space of the frieze before moving on to a discussion of ‘Mortalspace’ and ‘Divinespace’, their overlapping nature and what this might mean for the identity of the mortal men whose space they break into. To better understand the unique aspects of divine–mortal interaction depicted on the Parthenon frieze, I propose the use of two conceptual categories: ‘Divinespace’ and ‘Mortalspace’. ‘Divinespace’ refers to areas within the composition designated for divine figures, typically characterized by the presence of gods and their associated symbols. ‘Mortalspace’, conversely, denotes the areas occupied by human figures and earthly activities. These concepts are not merely spatial distinctions but represent conceptual realms that reflect ancient Greek perceptions of the relationship between the divine and the mortal worlds. The interaction and, at times, the transgression of these spaces on the frieze offer insight into the complex interplay between gods and mortals in Athenian religious thought and artistic representation. In some ways I am mostly interested in what the frieze can tell us about the contemporary religious landscape in Athens in the middle of the fifth century.

TIME-SPACE ON THE FRIEZE

Is the action of every part of the frieze occurring simultaneously and within the same space? Jennifer Neils’s tripartite reading of the action has been influential in answering this question. She views the action of the frieze in three distinct phases, the ‘time before’ (west face), the ‘time during’ (north and south faces) and the ‘time after’ (east face).Footnote 9 I am inclined to see the action on the frieze occurring simultaneously but multispatially, albeit with each part of the procession linked to the preceding and anteceding sections. Each aspect of the frieze occurs at the same time, from those individuals at the beginning of the route who have not yet left the gathering point outside the Dipylon Gate along the entirety of the procession to those who have already reached the Akropolis itself.

Beginning at the southwest corner, men are depicted readying themselves to depart.Footnote 10 They put on cloaks, steady their horses, and tie their shoes. These are some of the only figures which are not facing the direction of the procession. Thus, it is more likely that those men who are not yet ready to depart on the southwest corner are part of the procession which has not yet moved off from the Dipylon Gate, where the procession properly begins and where the Pompeion was built for this purpose in the fourth century.Footnote 11 This is common behaviour—people waiting their turn to start processing would (while fixing the final parts of their outfits, accessories and attending animals) turn around to chat casually with those in their section of the procession. This behaviour can be observed at any modern protest march or running race, where those who will take up the rear of the contingent can be seen standing facing one another while fixing signs, tying shoelaces and stretching, even while the front of the march or race is nearing the end. This matches the casual behaviour of the two men at the end of the frieze procession, who appear on the southwestern corner.

This portion of the frieze is the least densely populated. Yet, even though the figures do not touch or overlap, we can still see the tenderness of their relationship reflected in their representation. These men are likely demesmen and probably even friends. There is a juxtaposition between what I refer to here as a ‘casual unreadiness’Footnote 12 and the more formal, actively processing portions of the frieze. These more formal sections of the frieze, where the procession is actively moving down the Panathenaic Way, are most evident in the representation of horsemen, with stiff backs and well-reigned horses. The north and the south faces are roughly symmetrical with the prominent exception of the two sections of horsemen, where the south face shows a clear set of ten ranks of six, while the north face shows no such clear set of ranks.Footnote 13 Following these are chariots which most likely depict the apobatai,Footnote 14 followed by elders, who do not represent thallophoroi (‘branch-bearers’) as there is no space compositionally to include painted or attached branches,Footnote 15 then musicians, hydrophoroi (‘water-carriers’), skaphephoroi (‘tray-bearers’), sacrificial victims and herders. Juxtaposition occurs between individuals who are casually mingling about and those who are already in formal stances. Both states are appropriate: casualness when waiting and formality when performing. Because the ritual procession is a performance, this juxtaposition is mirrored on the other end of the frieze, at the east face, between the performance of the ritual participants and the ‘casual unreadiness’ of the gods. These groups of divinities on the east face exist in ‘Divinespace’. When one considers that the peplos scene shows (perhaps) the folding away of the previous peplos, rather than the statue being dressed in the new peplos, and that this possibly takes place within the Temple of Athena Polias (and therefore not in public view), it becomes unproblematic that the end of the procession has not yet set off. If we view the events of this central scene as taking place inside the temple (here, the Temple of Athena Polias, where the xoanon—the ancient wooden statue—was housed), then this is a liminal space that is betwixt and between the mortal and the divine. The internal space of the temple is of the divine; therefore, although the figures themselves are not, this may still be categorized as ‘Divinespace’, particularly given the porosity of ‘divine’ and ‘mortal’ spaces (as discussed below). Thus, to take this concept one step further, we can see all sanctuary space as both ‘Divinespace’ and ‘Mortalspace’ depending on the action taking place within it at any given time.

The east face, which is the front of the building, receives the flow from each end of the procession towards the centre. It is the only side that depicts women. This is clearly an intentional choice and maps onto what we can reconstruct of the festival in the Early Democratic period, when the participation of women and girls was perhaps more restricted than in later periods of the festival.Footnote 16 The south end of the east face shows the figure of a marshal (E1) who looks backwards to the procession that has come up the south face. In front of him is a row of sixteen heavily draped parthenoi (E2–E17), walking roughly in pairs,Footnote 17 carrying implements associated with sacrifice. Five of these figures carry phialai (shallow libation bowls), five carry oinochoai (wine jugs), and four carry two trumpet-shaped objects, which are perhaps incense stands.Footnote 18 At the front of this section are two who stand empty-handed. Their back-pinned mantlesFootnote 19 identify them as kanephoroi (‘basket-bearers’). Thus, it seems likely that they are empty-handed because they have turned their baskets in. The marshal who leads them (E18)Footnote 20 is engaged with the first man of a group of five (E19–E23), who are draped in a simple himation and set apart from the procession proper. Some scholars have identified this group of six men together, identifying them with four men on the opposite side, as the eponymous heroes; others have called them magistrates or dignitaries who preside over the ceremony. Whatever their identity, their role in the compositions (along with the figures who balance them out on the opposite side) is to facilitate the transition between the mortal procession and the scene in the centre of the east face, comprising the seated gods and the peplos scene. The north side of the east face shows a comparable scene, beginning with thirteen parthenoi (E50–E51, E53–E63), and four men (E47–E49, E52). Then a group of four more men (E43–E46) who are in the same role as the five on the opposite side. This makes the total group of these ‘elders’ nine (five on the south and four on the north). If we include either the marshal E18 (according to, for example, Evelyn Harrison and Jennifer Neils) or the central figure E34 in the peplos scene (according to Blaise Nagy and Ian Jenkins), this makes the total number of elders ten. This may correspond to the number of tribes, and if these men were identified as ‘eponymous heroes’, this would connect the scene more strongly with Kleisthenes’ democratic reforms of 507 b.c.e. While it may be that they are purposefully ambiguous in their design,Footnote 21 perhaps an attempt to firmly discern the identity of these figures is beside the point. Their unevenness may remind the savvy or philosophically minded ancient viewer that the ten Kleisthenic tribes (the total number of these men) were a reformation of the old tribal system of four (the number of men on the north side). So, they may represent both the ten current tribes and the four ‘original’ Athenian tribes. As the Parthenon is a victory monument,Footnote 22 they may evoke the ten generals, particularly in the minds of the many veteran soldiers. Similarly, they may represent the nine archons and the Panathenaia’s agonothetes (the ‘director of the games’); again, perhaps this reading is more likely for those individuals who are athletes or merely sports fans. These figures are placed between the procession-proper and the gods, indicating that they are meant to stand in the liminal space between the human and the superhuman worlds. Their height relative to the seated gods, as well as to the male figures on the frieze (see Fig. 1), indicates that they are mortal.Footnote 23 I shall return to these men below (in spite of my assertion that we should perhaps not worry about a firm identification).

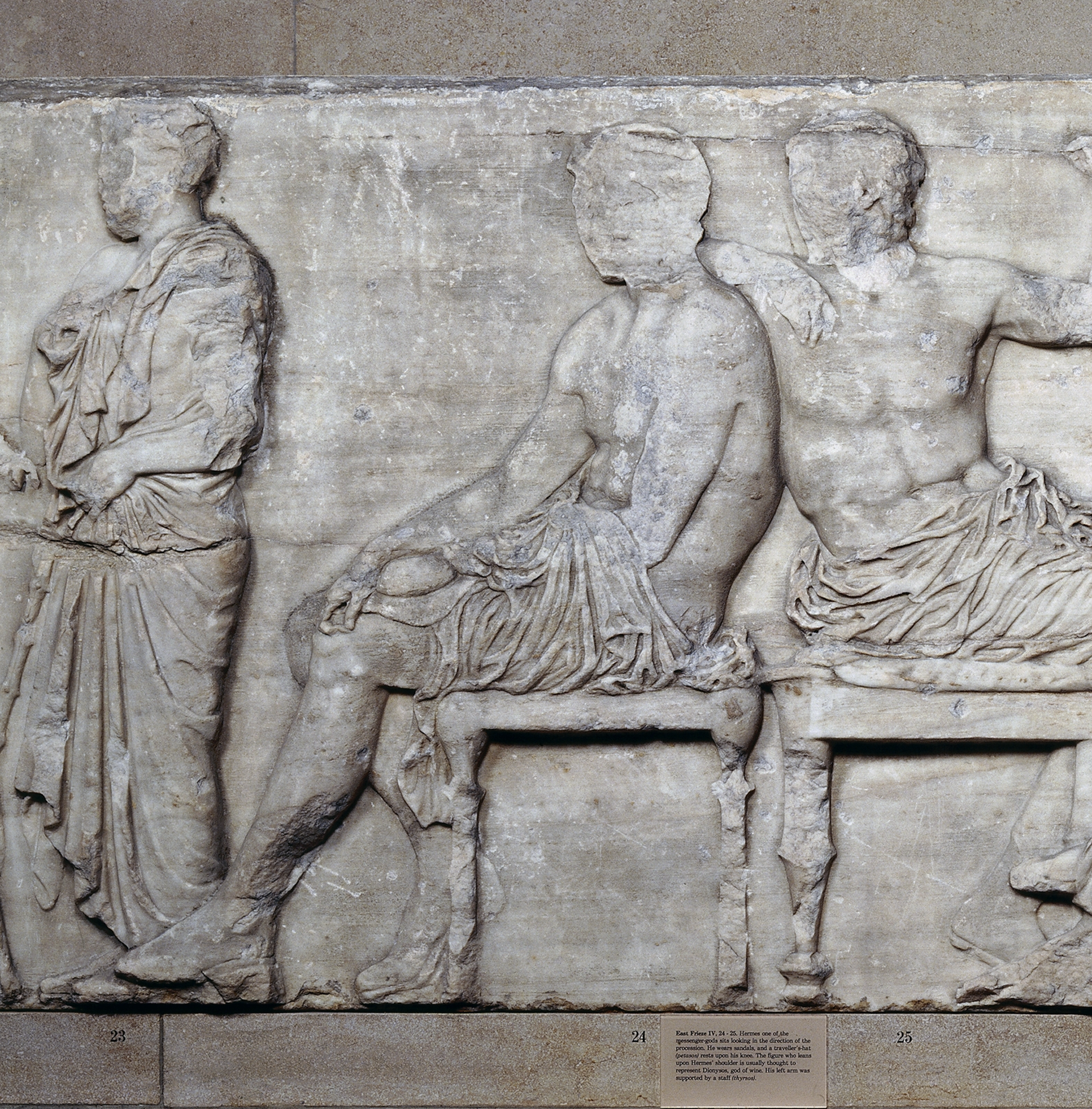

Fig. 1: Representative heights of male figures on the Parthenon Frieze, from L to R; South XLI figures 123, 124, West I figure 1, North XLVII figures 133, 134, East IV figures 20, 21. Pentelic marble low-relief carving, 442–438 b.c.e. British Museum, 1816,0610.87, 1816,0610.46.a, 1816,0610.46.b, 1816,0610.18.

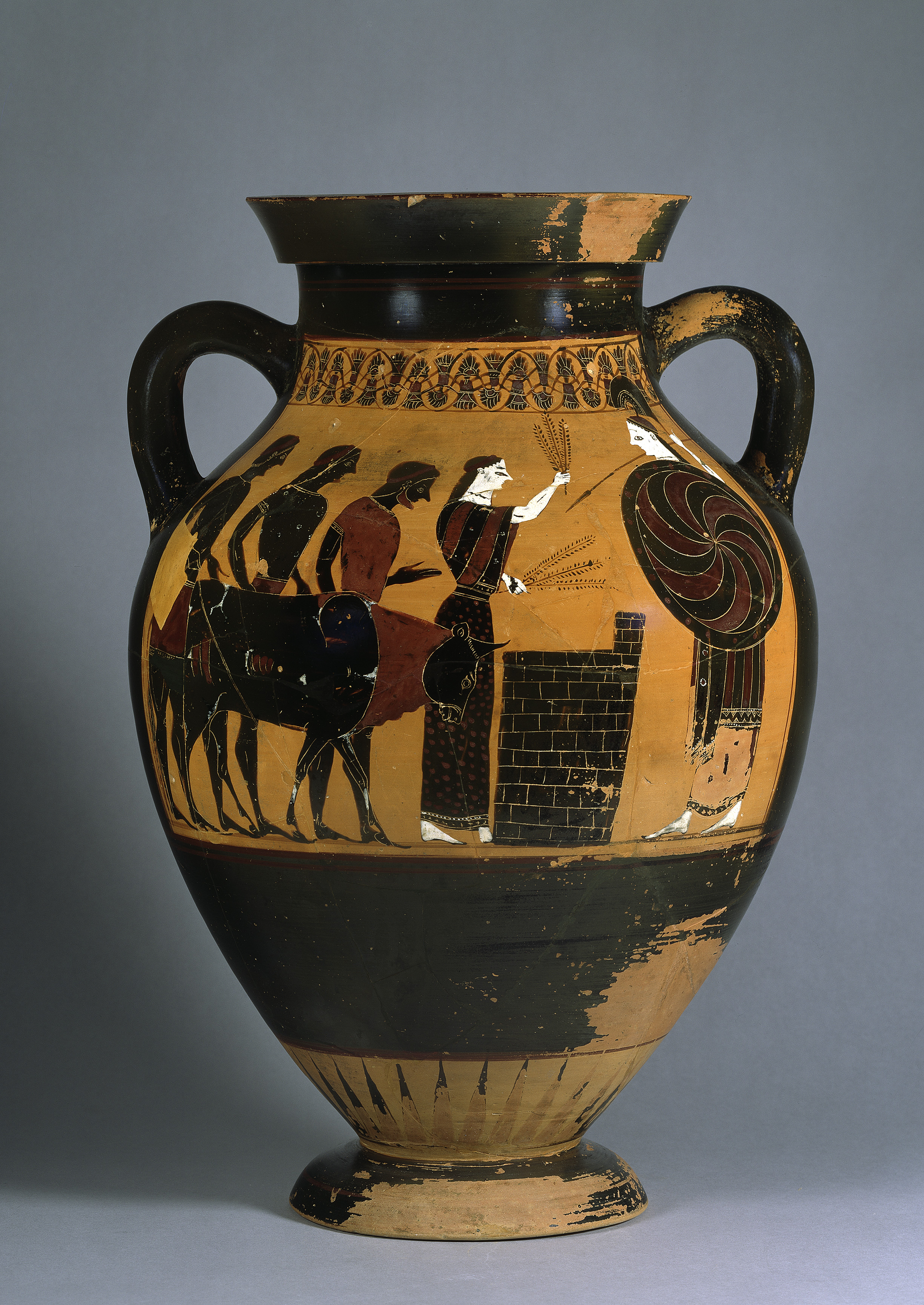

The seated gods surround the peplos scene, in the middle of this group of ten men (E18–E23, E43–E46). Gods frequently appear as active participants in ritual scenes in Greek art, often in a position indicating that they are accepting sacrifices or other offerings. A well-cited example is a black-figure Athenian amphora from c.550–530 b.c.e. (Fig. 2), now in the Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin; this amphora shows Athena, in her guise as Promachos (armed, wearing the aegis and gorgonian, in the ‘warrior’ pose), standing behind an altar. In front of the altar, a woman (the priestess?) holds up branches while three men accompany a bull. Similar scenes occur in various media, including votive plaques with many different divinities. The gods are depicted dynamically, with significant movement through the two groups. They are casual, as though chatting while waiting for the procession to end and the festivities to begin. On the south side, the first god, Hermes, is identifiable by the petasos (‘travellers’ hat’) that lies in his lap. This state of undress continues with several other gods, contributing to the ‘casual unreadiness’ of the divinities as a whole. The next figure is Dionysos, who leans over Hermes’ shoulders, looking towards the procession. Demeter sits facing the pair, and the group is completed by Ares, who leans slightly back, passive-aggressively gripping his knee.Footnote 24 Removed somewhat from Ares and standing behind the seated Hera is Iris, the messenger goddess, Hebe, the goddess’ daughter, or Nike, the victory goddess.Footnote 25 This side is finished with Hera, holding out her veil, and Zeus, king of the Olympians. Hera is turned towards the front, but she twists back to face Zeus, who had one elbow propped over his backrest, leaning in a relaxed pose. On the other side of the peplos scene is Athena, with her snaky-fringed aegis resting in her lap, mirroring Zeus’s posture. She faces Hephaistos, who had strong connections to the myth of Athenian autochthony. He has a crutch supporting his arm, a subtle nod to his disability. Following this is Poseidon, who looks away from the pair and towards the procession, brushing Apollo’s shoulder. The younger god looks back towards the elder, in conversation. Next is Artemis, who is also facing the procession and adjusting her chiton, which has slipped off her shoulder. Seated next to her, at the end of the line of gods, are Aphrodite and Eros. The way these gods are presented are clearly a representation of the relationship the Athenians feel they have—or aspire to have—with these gods. We can tell this by the way in which Athena is presented: relaxed, her aegis in her lap, waiting for the brand new dress she is about to receive from her favourite people.

Fig. 2: Black-figure amphora, c.550–530 b.c.e., Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung F1686 (CC BY-SA 4.0).

In the middle of the seated gods is the peplos scene, which should be read as contemporary to the procession, but it is marked apart from the rest of the frieze by its position between the two groups of gods and directly above the entrance to the building. In the exact centre is the image of the Priestess of Athena Polias (E33). Standing to her left are two young girls (E31–E32), arrhephoroi, carrying trays that most likely contain cakes. On the other side is a priest, identifiable by his dress, and an attendant, folding up the peplos. I have previously argued that this scene represents a triptych showing the past, present and future peploi, which thus represents an ongoing cycle of offerings from Athens and the Athenians to Athena.Footnote 26

THE FRIEZE AS A VOTIVE

The Panathenaic procession is an offering to the goddess that is part of the overall programme of the festival.Footnote 27 The Ionic frieze then can be understood as a physical model of the procession: a votive offering. Just as other votive dedications are often models of real objects (animals, cakes, clothing, weapons, body parts) or religious rituals, the frieze serves as a physical model, a representation of the offering that is the procession continually repeated over time. It is a physical object that brings the memory of the offering event(s) to the fore. This works the same way as any other votive offering; for example, a statue base found on the Akropolis dating to the early fifth century says ‘Maiden, Telesinos of Kettos dedicated the statue on the Akropolis. Please take pleasure in it and grant me to dedicate another.’Footnote 28 The statue was dedicated to Athena by Telesinos, both in the hopes that the goddess would delight in it as an offering and that she might grant Telesinos the fortune to be able to dedicate another in the future. The entire Parthenon and its iconographic programme say the same in not so many words.

In part, the function of the frieze is to delight Athena so that she may give the city the prosperity and fortune to continue to dedicate offerings to her. The frieze, though, works in several other, interlinked ways. It represents the procession and everything that the city put into the procession as the crowning point of the festival. Each part of the festival and the procession is represented: animals for sacrifices (including evoking the ‘ancient’ tradition of offering ewes to Pandrosos when Athena is offered cows);Footnote 29 athletes, including from the (in)famous Athenian-only apobatai;Footnote 30 musicians; thallophoroi; men and women carrying ritual objects; the ever-important peplos. Thus, it reminds the goddess of the procession and the rest of the festival, including its athletic games. It alludes to the movement of the procession, recalling the sensory responses of anyone who has participated in, or witnessed, the procession—more or less all Athenian citizens and residents—and thus evoking sensory memories of actual events participated. Finally, it contains images of the two main offerings that cap the procession: the hecatomb sacrifice represented by the bulls on the south and north faces and the peplos dedication on the east face. This does not require the frieze to be visually available to people; therefore, the difficulty of viewing the frieze is inconsequential. This is because the primary audience for the offering is not the human visitor to the site but the divine—specifically, Athena. However, there must have been a certain amount of understanding about the subject matter on the frieze and its importance among both residents and foreign visitors to the city.Footnote 31

Why did the procession, itself a dedication to the goddess, require a permanent reminder in the form of a votive? The votive, or ἀνάθημα,Footnote 32 can vary widely in form. Many votive reliefs, for instance from Attica, feature processions approaching a divinity and undertaking ritual activities. The vast majority of these are votive offerings.Footnote 33 Many of these were displayed as though artworks within the temple complex,Footnote 34 and a large number of those found on the Akropolis are from the Persian destruction layer.Footnote 35 Such works are self-referential; they visually describe the procession and its participants, often standing at an altar with sacrificial animals. Kyriaki Karoglou comments that votives ‘betray’ the identity of their dedicators: not their character or piety but their socio-economic status. This is, she comments, related directly to the size of the offering and the cost of its materials,Footnote 36 and these combine to demonstrate ‘spiritual value’. In addition to this, the labour involved in constructing an offering needs to be factored in, from small ‘production line’ relief carvings to more significant, bespoke offerings. As an offering to the goddess, the Parthenon’s Ionic frieze demonstrates high levels of ‘spiritual value’ because of its cost, size and labour intensiveness and because it follows a more traditional line of ‘combining’ smaller-cost votives into a more impressive object.Footnote 37 Votives, as other dedications, perpetuate the ongoing and reciprocal relationships between people and the gods. Following the Persian destruction of the Akropolis, including the loss of many votive objects, these avenues of invoking the human–divine relationship were lost. Just as the melting down of multiple smaller offerings to create one offering that was more pleasing, the Parthenon (and thus also the frieze) memorializes the Athenians’ perpetual relationship with Athena, which had previously been displayed on the Akropolis through the number and variety of individual votives, but which could now be shown through one collective and civically minded votive. In this way the Parthenon as a whole and the frieze as a particular part of it similarly ‘betray’ the religious landscape of Classical Athens, both (as previously stated) in the depiction of the gods and in the depiction of their own performance of piety.

‘DIVINESPACE’ ON THE FRIEZE

‘Divinespace’ refers to the specific space within a composition designated as belonging to the divine realm.Footnote 38 This is most often indicated, as it is on the frieze, by the depiction of the gods, or less often through visual cues that signify their presence. ‘Real world’ sacred spaces, such as temples or altars, are not ‘Divinespace’ on their own unless a divinity or some other indication of the divine is present, or unless there is active religious practice being undertaken (as we find, for example, with the designation of the frieze’s peplos scene as ‘Divinespace’). ‘Mortalspace’ refers to the space within a composition designated as belonging to the mortal realm, primarily represented by human figures. Such spaces focus on the portrayal of human activity and narratives.Footnote 39 There are instances where ‘Divinespace’ and ‘Mortalspace’ intersect or overlap within artistic compositions. These intersections can involve representations of mortals crossing into the divine realmFootnote 40 or divinity interacting with mortals within their designated space.Footnote 41 There may also be conduits, such as divine animals or ritual implements, which breach the divine between the spaces. These objects serve as symbolic connections between the divine and the mortal spaces.

The gods on the frieze can be split into two main groups, those closest to the central scene (Hera and Zeus on the north side, and Athena and Hephaistos on the south) and those closest to the procession (Hermes, Dionysos, Demeter and Ares on the north; Poseidon, Apollo, Artemis and Aphrodite on the south). The most persuasive argument for the arrangement of the gods in physical space was originally proposed by Arthur Smith in 1910Footnote 42 and was later revived and expanded by Neils.Footnote 43 This posits that the gods are seated in a semicircle around the central peplos scene, with Zeus and Athena together at the back and working through the gods until Hermes and Aphrodite meet the oncoming procession. In part, this theory gained traction because it answered one of the fundamental questions we have about the frieze and its composition: why are the gods ignoring what is meant to be the most important aspect of the work—namely, the ritual being observed in the very centre? I am more inclined to see the ‘packing away’ of the peplos occurring inside Athena’s temple, and therefore being hidden from view.

The first group of gods are those who are contextually more important here, Zeus and Hera because they are the king and queen of the Olympians and therefore important in the schema of the pantheon, and Athena and Hephaistos because of their direct involvement in Athens and its autochthonous foundation mythology. I am here more interested in the groups of contextually less important gods. These groups are characterized by their closeness to one another. All are either directly touching or crossing into one another’s space. This is a representation of family members at a relaxed event—for instance a barbecue—rather than at a formal gathering. The most obvious rendering of this, which unfortunately is also the least well preserved, is the relationship between Artemis and Aphrodite (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2).

Fig. 3.1: Parthenon Frieze, East VI, figures 40–2. Pentelic marble low-relief carving, 442–438 b.c.e. Akropolis Museum, Athens, Akr. 856.

Fig. 3.2: Parthenon Frieze, East VI, figures 40–2. Pentelic marble low-relief carving, 442–438 b.c.e. Akropolis Museum, Athens, Akr. 856. Drawing by M. Korres.

This is an image of two goddesses who are not commonly associated with one another elsewhere in religious practice or in art,Footnote 44 behaving in an incredibly intimate way. Although they do not look at one another, their closeness is evident. Aphrodite leans back, her forearm resting on Artemis’ thigh. Artemis has passed her arm through the crook of Aphrodite’s elbow. Aphrodite, shown in a three-quarter view mirrored in other divinities on both sides, appears relaxed. Her left arm reaches over the shoulder of the diminutive nude Eros, who stands in front of her, looking after her pointed finger towards the procession. He leans back on her thigh, his hand tucked under the fold of her himation, which rests on her lap. Her feet are crossed right over left and are placed in front of the standing mortal figure who faces away from her. We see this clearly in the cast made by L.S. Fauvel in 1787 under the orders of Count Choiseul-Gouffier, then French ambassador to Constantinople, and confirmed by Jacques Carrey’s drawing.Footnote 45 There is a similar parallel on the other side. Like Aphrodite on the south, Hermes is the closest of the gods to the procession on the north side (Fig. 4). As on the south side, we find Hermes’ foot crossing into the procession space, in front of the final mortal man (E23). On both sides, then, we find the gods breaking out of their own space and into ‘Mortalspace’. Is this kind of cross-over common in other comparable representations of religious action?

Fig. 4: Parthenon Frieze, East IV, figures 32–5. Pentelic marble low-relief carving, 442–438 b.c.e. British Museum, 1816,0610.18.

‘MORTALSPACE’ INTO ‘DIVINESPACE’

To investigate this, I will examine some votive images, including both relief carvings and painted pinakes (‘plaques’), which are comparable both iconographically and contextually. My primary examples have all been taken from the Athenian Akropolis in the Archaic and Classical periods, but this represents a wider sample. Votive images are useful to study iconographically as we know that they have a primarily dedicatory function, and this changes very little over the period we are concerned with. Votive images, as Kyriaki Karoglou states, in the context of painted versions, ‘call attention to the relationship, if any, between the image and cult of a god’.Footnote 46 We find several different types of human–divine interaction in such votive images, including those which are purposeful and, sometimes, mediated, those which occur in strictly ‘Divinespace’, and those which occur in ‘Mortalspace’. In most cases, we find mortals and divinities separated within the composition, sometimes by an altar or animal, less frequently by empty space or by other appropriate conduits, including ritual implements. There are cases where divinities do not appear to notice the mortals who approach them (for instance in the common composition showing a worshipper approaching Aphrodite and Ares, who are engaged in communication with one another).Footnote 47 We find examples where divinities touch mortals in specific ways,Footnote 48 and examples where there is clear delineation of space between mortals and divinities. However, as with so many other aspects of the frieze, the way in which space is crossed is unparalleled in other art.

One votive offering, from around 500 b.c.e., was found to the east of the Parthenon in 1883 (Fig. 5),Footnote 49 along with other fragmentary material destroyed by the Persian sack of the Akropolis in 480. This means that we cannot know where it might have originally been displayed on the Akropolis and that we have thus lost some of the context associated with its original dedication. The pinax shows a family of two adults and three children presenting a pig to Athena as sacrifice. As often in Greek art, the mortals are depicted as smaller than the divinity, as is standard iconographic practice.Footnote 50 This is the first extant instance of a relief pinax showing Athena as a recipient of cult offerings,Footnote 51 but—more than this—it gives an impression of a goddess who is in direct communication with her mortal worshippers and is the first in a long line of ‘adoration’ offerings.Footnote 52 These scenes place divinities and worshippers face to face, allowing this closeness to be a visual articulation of the multidirectional relationship created between them in the act of worship. This scene has been interpreted as an offering to Athena Phratria,Footnote 53 protector of local kin groups, possibly dedicated during the Apaturia festival.Footnote 54 Perhaps it was dedicated during the official presentation of the two boys, shown leading the sow towards the goddess, and therefore articulates the special relationship that is forming between the young boys and Athena, the beginning of their lifelong reciprocal relationship. Athena grasps the central pleat of her long Ionic chiton, pulling it away from her body, in a gesture familiar from korai statues from the same period.Footnote 55

Fig. 5: Parian marble low-relief carved votive plaque, c.490–480 b.c.e. Akropolis Museum, Athens, Akr. 581.

Here Athena has manifested herself in front of the family of worshippers, watching on as they offer up their sacrificial animal. The family processes forward, although there is a very slight crossover between the goddess and the boy at the front, who appears to be holding up a phiale for the pouring of libation, which crosses behind the folds of Athena’s chiton. Even with this crossover, there is a clear differentiation between the space of the goddess and the space of the mortals. The ritual implement, as an object of doing religion, bridges this gap, creating a conduit between ‘Divinespace’ and ‘Mortalspace’ that is both appropriate and understandable. This is an implement with which the family shall honour the goddess. The boy’s posture even indicates that he is in the act of pouring the libation, further strengthening the supposition that this object—and the religious act associated with it—appropriately breaks the divine between the spaces. We can find many examples of similarly appropriate conduits which break the divine between ‘Divinespace’ and ‘Mortalspace’ in votive images and in other media, including on vase paintings. In these examples, we see individuals and groups approaching the divinity with a sacrificial animal or with some other form of deed—whether a sacrifice, offering or performance.Footnote 56 This captures the offering of the animal to the divinity before the sacrifice. There are very few visual representations of the act of sacrifice itself, and these almost exclusively occur on vases.Footnote 57

We can deduce, based on the type and number of fragmentary painted terracotta pinakes found on the Akropolis (Karoglou cites 144 in total, including 113 from the Akropolis itself, and 31 from two wells on the north slope),Footnote 58 that the painted versions share iconography with the relief-carved types. This body of evidence, however, is in worse condition than the relief carvings owing in part to their context of deposition, having mainly been recovered from the Persian destruction pits, and the more fragile nature of the material. There are several that we can identify as adoration scenes between a worshipper and Athena,Footnote 59 but only one of which (Fig. 6) can be analysed in any meaningful way regarding the space between Athena and the worshipper. In this scene we find Athena walking to the left. Only her back is preserved. A female worshipper follows her, making a gesture of piety. We cannot discern whether Athena herself is depicted in a position of awareness of the worshipper’s presence. While there is a clear empty space between the goddess and the worshipper, the space is intruded into by the snakes that fringe Athena’s aegis, creating a conduit between the goddess and the mortal who follows her.

Fig. 6: Black-figure painted terracotta pinax, c.560 b.c.e. Hellenic National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Akr. 2540. Photograph by the author.

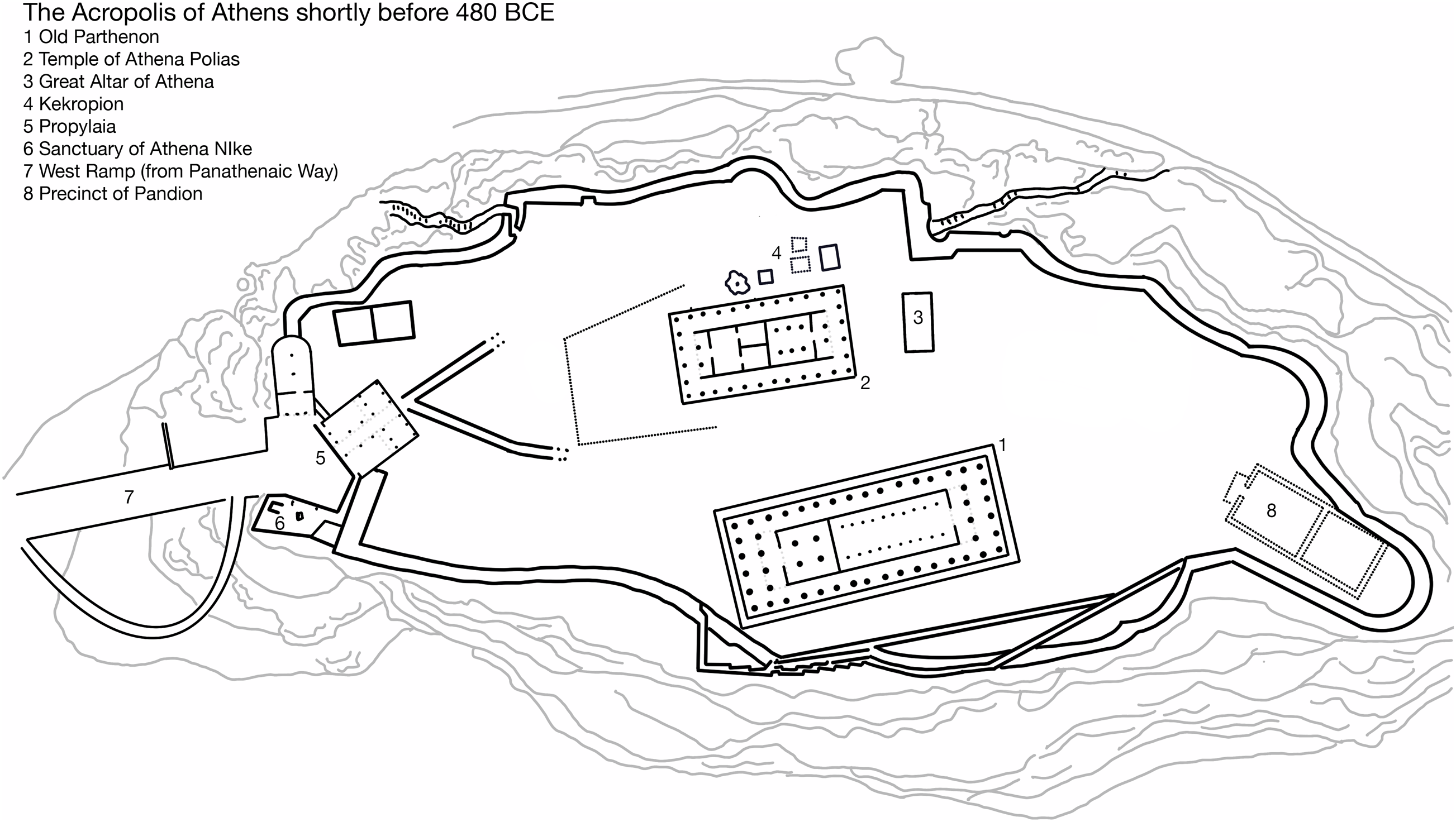

These pinax types capture the moments before people undertake sacrifice or show people undertaking ritual performances, including a procession, the pouring of libation and the giving of dedications. The mortal worshippers are physically bringing themselves and—crucially—their offerings into the realm of the divinity. The fact that they bring the accoutrements of religious practice means that they can break into ‘Divinespace’. But it is they who are doing the breaking. This is to say, it is the mortal worshippers who are bringing themselves into the realm of ‘Divinespace’, both physically—into the space of the sanctuary—and metaphysically—into the space of the ritual itself. This is also evident on the frieze, where we find a significant number of sacrificial animals, ritual implements and the performance of procession. As I have previously discussed, the action on the frieze culminates, on the east face, on the Akropolis itself, and we are situated somewhere around the Temple of Athena Polias (see Fig. 7), inside which the main offering of the peplos will be made, and outside of which will be the sacrifice of animals. Although the layout of the Akropolis changed slightly after the rebuilding programme of the mid fifth century, this would still dictate the physical format of the Panathenaic festival, with the main altar unmoved and the cult function of the earlier Temple of Athena Polias moved into the temple we now call the Erechtheion. Just as we find on the examples from votive images, the processors of the Panathenaic procession represented on the frieze are bringing themselves into the physical space of the divinity. And yet there is a key difference between what we find in each of these instances.

Fig. 7: The Akropolis shortly before 480 b.c.e. Illustration by the author.

‘DIVINESPACE’ INTO ‘MORTALSPACE’

Before we move onto an elucidation of that key difference, we must look at one last piece of comparative evidence from the votive images. There are, of course, examples in which divinities and humans do engage in mutual touch. There is, for instance, a relief (Fig. 8) which shows Athena directly receiving an offering from a seated mortal, often interpreted as an artisan of some kind, but recently reinterpreted by Neils as one of the tamiai—officers of Athena Polias who kept accounts and inventories of her wealth.Footnote 60 This, then, represents Athena Polias entering into the liminal half-space between the divine and the mortal spheres, demonstrating ever more clearly the porosity between the two. Athena here brings herself into contact with the sacred treasurer, appearing epiphanically to him. We know this because the treasurer is seated, engaged in work, and Athena moves forwards towards the man, with right foot in front of the left, and reaches out with her right arm to accept the gift. The treasurer stretches his right arm up to meet the goddess. Athena accepts his offering directly as a trusted official. We might compare this to Athena Phratria receiving two young boys on the occasion of them being sworn into their phratry. The exchange here is taking place within the context of a personal relationship that has been cultivated, over time and with repeated observance, between the man and the goddess.

Fig. 8: Pentelic marble low-relief carved votive plaque, c.470–460 b.c.e. Akropolis Museum, Athens, Akr. 577.

Another type is characterized by an honorary decree found on the Akropolis in pieces over several excavations (Fig. 9). The stele marks the occasion on which the Athenian state gave the titles of proxenos (‘ambassador’) and euergetes (‘benefactor’) to a non-Athenian man named Proxenides of Knidos. The recipient of these honours is flanked by Aphrodite on the left, the patron of Knidos, who is presenting Proxenides to Athena, the patron of Athens. Here Athena ostensibly represents Athens to the outside world rather than to the Athenians themselves. However, the context of the carving suggests that this is an ‘internal–external’ image, rendering Athena to the Athenians but through the (fictionalized?) lens of non-Athenians. Aphrodite here acts in a similar way. She is the Knidian Aphrodite as the Athenians see her. The subject matter of the stele is clear: one divinity is presenting her subject to another divinity, whose people are honouring him. While Proxenides is placed between the two divinities, and clearly within ‘Divinespace’, the primary relationship being mediated is between the two goddesses as patrons of their individual poleis. Proxenides has no agency here, although he demonstrates an awareness of the role he has to play in the proceedings. He is fully cognisant of the two goddesses, and they each acknowledge his presence—Aphrodite on the head, as though calming a child, and Athena with a handshake.

Fig. 9: Pentelic marble relief stele, c.420 b.c.e. Akropolis Museum, Athens, Akr. 2996.

On the frieze, neither of the gods who cross into ‘Mortalspace’ is acting in the ways demonstrated in our example votive images. They do not receive either collective or individual benefaction from the mortal worshippers, and they are not acting as divine agents for communities of people (whether large political bodies like poleis or groups bound together by shared purpose like professions). Both divinities have interesting and complex religious roles in Athens in their own rights. Aphrodite particularly is interwoven with the religious practice on the Akropolis—as Jeffrey Hurwit comments, ‘if Athena was the preeminent goddess of the summit of the rock, the preeminent goddess of its slopes was Aphrodite.’Footnote 61 She was worshipped on the west slope, in a shrine located below the Nike Temple, as Pandemos (‘All the people’), alongside the goddess Peitho (‘Persuasion’). In this guise, she facilitates the goodwill required within the citizen body to continually promote democracy. The pair of goddesses also appears in wedding-related iconography together, an aspect which marries her roles as both goddess of civic togetherness and sexual union, via the production of legitimate children to facilitate the continued propagation of the demos.Footnote 62

Hermes is slightly more difficult to find. As Henk Versnel points out, ‘although he is one of the most popular and often mentioned deities of the Greek world, hardly any official (polis-)cult and cult-places of the god is known … In Athens, as far as we know, Hermes had no temple and no festival.’Footnote 63 Hermes’ origin lies in Mycenaean Greek, his name perhaps derives from the herma, to which he is certainly connected. These are stones laid out with the specific purpose of boundary demarcation. By the late sixth century, hermai were not only demarcation stones but also protective figures.Footnote 64 Hermes was a ritual boundary-crosser, embodied by the immovable stone hermai, but more clearly found in his role as a divinity who crossed the path between the living world and the Underworld. He is the only god who can traverse that path without assistance, and is often (as is the case with, for instance, Persephone) the god who provides that assistance to others.Footnote 65

While it is true that the festival being depicted on the frieze is not a celebration of these two gods, the fact that they are on the furthest periphery of the group(s) of gods is important and plays into each of their roles with regard to their closeness with Athenians.Footnote 66 Aphrodite assumes guises that directly support the perpetuation of the democratic demos, either by emotionally eliciting feelings of goodwill and togetherness, as in her role as Pandemos, or by the more fundamentally physical aspect of actually perpetuating the growth of the population, through sexual activity.Footnote 67 Hermes, similarly, has roles as psychopompos (‘guide of souls’) and as a god who attends births and guides Athenians throughout their lives in the guise of herms. They are the conduits between more important (in this specific context) divinities and the procession. In part, this is because they are closely connected to the mortal realm. But they do not cross directly into the general flow of the procession. There is a second group, this time of mortals, who are also conduits between the procession and the gods, as Hermes and Aphrodite are between the gods and the mortals.

‘MORTALSPACE’ ON THE FRIEZE

This group of mortals comprises, of course, the ambiguous men who are identified sometimes as the eponymous heroes and sometimes as marshals. Nagy has very convincingly argued that these men are the athlothetai, a group of ten officials who administer various aspects of the Panathenaic festival, including the provision of the peplos. This identification sees the figures on either side of the gods (E19–E23 and E43–E46) as the main group of athlothetai, and the figure in the central scene (E34) who is handling the peplos as the appointed ‘principal athlothetes’ of the group.Footnote 68 And it is with these men that the ‘Mortalspace’ on the frieze ends. It is clear from the way in which they behave that they are not actively processing, as is evident in other parts of the composition, and particularly down the two longer sides. The final groups of active processors are the parthenoi on the east face. The marshals who direct them (E18, E47–E49, E52) are not themselves processing, but are facilitating the procession. Their role is typified by E18, who is conversing with the final athlothetes, acting as a pivot between the flow of the procession and the group of men. This is not replicated on the north side, because these groups of marshals are undertaking two different aspects of their role—taking the baskets from the kanephoroi (E48–E49, E52) and acting as transitions to the central figures (E18, E46). These kinds of transitional figures are common throughout the composition.Footnote 69 Looking down the remainder of the procession, examples of this obvious forward motion are evident throughout, from the animals with handlers to the horsemen who dominate the back half of the building. The frieze is replete with examples that demonstrate this dynamic composition flowing towards the east end and the finale of the procession.

In contrast, the group of athlothetai, broken unevenly between the two sides, are not moving or facilitating the movement of others. They are passive observers—in some ways portrayed with much of the same air of casualness as the gods but with less intimacy in their depiction. For example, figures E20–E23 do not share the same intimacy as the gods on either side of the peplos scene, particularly those groups closest to the mortals. This is evident by their physical detachment form one another. The only pair of the group to display this physical intimacy are figures E44 and E45, where the older of the two (indicated by his beard compared to his companion’s beardlessness) leans back onto the younger. Both mortals and gods are relaxed, chatting amongst themselves, depicted with more than a passing familiarity. This familiarity befits a family, as the gods are, and also officers who have been working together for several years (as I shall explain below). It is also clear that these men are supposed to be set apart from the other mortals by their individualization. Ian Jenkins comments that, although we can only certainly attribute sticks to eight of the figures, it is likely that all nine had them.Footnote 70 However, we should not consider this a marker of the office, since at least some of the marshals on the frieze also have them, and they are an iconographic indicator of Athenian citizens elsewhere in Classical art. Neils points out that the heads of the four men on the north side, which are far better preserved than those on the south, are ‘highly individualized, almost suggesting portraiture’,Footnote 71 and this strengthens the argument as these figures should be set apart from the rest. They are not, however, semi-divine (as, for instance, if they were the eponymous heroes), since both of them interact directly with the mortal processors (not only are figures E18 and E19 conversing but E18 is also touching E19, his left hand grasping the other man’s arm above the elbow, and his right hand in a gesture of indication). They face one another and are clearly engaged in conversation. On the other hand, although the ‘Divinespace’ crosses into ‘Mortalspace’ at the other end of each group—with Hermes and Aphrodite—none of the mortals recognizes this crossing of space.

Neils also contends that, if these men were officials, they would be shown performing their duties, as the marshals throughout the composition are. I want to contend here that they are indeed officials—as I have stated, following Nagy’s assertion that they represent the athlothetai—and that they are being depicted performing the tasks they would be assigned on the day of the procession.

We learn a little about these men from Ps.-Aristotle’s Constitution of the Athenians, which tells us that ten officials were elected by lot, with one from each of the ten tribes, and that they held their office, unusually, for four years, an entire Panathenaic cycle, and that they administered the Panathenaic procession and the games ([Arist.] Ath. Pol. 60.1, transl. Rackham):

κληρο![]() σι δὲ καὶ ἀθλοθέτας δέκα ἄνδρας, ἕνα τ

σι δὲ καὶ ἀθλοθέτας δέκα ἄνδρας, ἕνα τ![]() ς ϕυλ

ς ϕυλ![]() ς ἑκάστης. ο

ς ἑκάστης. ο![]() τοι δὲ δοκιμασθέντϵς ἄρχουσι τέτταρα ἔτη, καὶ διοικο

τοι δὲ δοκιμασθέντϵς ἄρχουσι τέτταρα ἔτη, καὶ διοικο![]() σι τήν τϵ πομπὴν τ

σι τήν τϵ πομπὴν τ![]() ν Παναθηναίων καὶ τὸν ἀγ

ν Παναθηναίων καὶ τὸν ἀγ![]() να τ

να τ![]() ς μουσικ

ς μουσικ![]() ς καὶ τὸν γυμνικὸν ἀγ

ς καὶ τὸν γυμνικὸν ἀγ![]() να καὶ τὴν ἱπποδρομίαν, καὶ τὸν πέπλον ποιο

να καὶ τὴν ἱπποδρομίαν, καὶ τὸν πέπλον ποιο![]() νται, καὶ τοὺς ἀμϕορϵȋ;ς ποιο

νται, καὶ τοὺς ἀμϕορϵȋ;ς ποιο![]() νται μϵτὰ τ

νται μϵτὰ τ![]() ς βουλ

ς βουλ![]() ς, καὶ τὸ ἔλαιον τοȋ;ς ἀθληταȋ;ς ἀποδιδόασι.

ς, καὶ τὸ ἔλαιον τοȋ;ς ἀθληταȋ;ς ἀποδιδόασι.

[The nine archons] also elect by lot ten men as Stewards of the Games, one from each tribe, who when passed as qualified hold office for four years, and administer the procession of the Panathenaic Festival, and the contest in music, the gymnastic contest and the horserace, and have the peplos made, and in conjunction with the Boule have the vases made, and assign the olive-oil to the competitors.

We can assume, since Perikles was elected to the position sometime in the 440s,Footnote 72 that before Aristotle’s time selection was not by lot but by direct election. There is corresponding epigraphic evidence from later in the fifth century, including records of the athlothetai being allocated large sums of money to pay for the games, prizes and the peplos. In 415/14, Amemptos and his colleagues were given nine talents on the twentieth day of the second prytany to cover the festival’s expensesFootnote 73 (presumably this was an advance payment for expenses related to the Greater Panathenaia of 414 b.c.e.) and five talents to Philon of Kydathenaion and his fellow officials in 410/9 b.c.e. following the restoration of democracy in Athens, and so with presumably a significantly emptier treasury than in other years.Footnote 74 A dedication commemorating the institution of the Greater Panathenaia in 566/5 b.c.e. mentions that the athlothetai organized either the equestrian races or possibly the racetrack, perhaps a reference to the non-permanent dromos.Footnote 75 Later epigraphic evidence, in the form of a decree honouring the athlothetai and dating to 239/8 b.c.e. mentions some of their duties as including musical, gymnastic and equestrian competitions, ‘and everything else that fell to them’.Footnote 76 So we can conclude that the three main tasks of the athlothetai included organizing the procession, organizing the games, and arranging the production of the peplos. It is most likely that the competitive events would occur first, and the procession and sacrifice would be the final major event of the festival.Footnote 77 This means that the athlothetai would have completed their assigned tasks at the moment represented on the frieze: the peplos has been made and either has been presented or will imminently be presented to the goddess, the procession has been organized and is running as planned, the games are over. The role that these men now have to play is that of a relaxed host.

CONCLUSION

The issue, then, does not lie in the appropriateness of Aphrodite and Hermes as boundary-crossing divinities, although that certainly has a role in this depiction. Rather, it is the question of whose space is being crossed into. The athlothetai serve terms of four years, whether or not they have a role to play in the organization of the annual Lesser Panathenaia in this period (though they certainly do so by the mid second century b.c.e.).Footnote 78 They had been thinking about, and planning for, this specific festival for the previous four years. Studies have demonstrated that contemplation and active work towards religious goals equate to increased awareness of the divine.Footnote 79 Still, even if we cannot directly ascribe these men with increased modes of belief, we must consider this iconographically appropriate to represent on the frieze as a votive offering to the divine. It should not surprise us that the state would want to depict these men—non-religious officials undertaking the organization of the most important religious event in Athens—undertaking an act that has demonstrably brought them, and therefore all Athenians, closer to the gods. The casual nature with which Aphrodite and Hermes break into the ‘Mortalspace’—unnoticed and without fanfare—confirms this point. This represents a group of men who have become used to mediating between the citizenry and the gods. Regardless of their actual participation in the organization of the Lesser festivals, they have been through three ‘practice runs’ before getting to the point shown on the frieze. They are relaxed because their job is complete and (as befits an idealized representation of the festival procession) done well.

There is something interesting, too, in the complete lack of awareness that the mortals have of the gods, not just of their breaking into ‘Mortalspace’ but in total—this does not fit the relationship we find between gods and mortals in other votive relief sculptures. Put simply, this is not the normal, small-scale family sacrifice that we find on many votive pinakes. These men act as an intermediary between the gods and the procession precisely because they have facilitated this offering—the games, the procession and the peplos—between Athens and Athena.

In conclusion, the portrayal of gods crossing into mortal space during the Panathenaic procession challenges traditional expectations. It raises intriguing questions regarding the role of the athlothetai and the deeper symbolism at play. The interplay between mortals, gods and the context of the frieze offers a fascinating area for continued scholarly investigation and invites further exploration into the intricacies of ancient Greek religion, art and society.