Refine search

Actions for selected content:

2323 results in Ethnomusicology

Appendices

-

- Book:

- Alphons Diepenbrock

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 09 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2023, pp 393-394

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

21 - Scenes from Provincial Life

-

- Book:

- Composing Myself

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 09 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2023, pp 303-312

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Propaganda Tool in Berlin

-

- Book:

- Composing Myself

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 09 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2023, pp 200-205

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - The Music

-

- Book:

- Alphons Diepenbrock

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 09 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2023, pp 267-392

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Letters of Gerald Finzi and Howard Ferguson

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 23 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 July 2001

A History of Music at Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 20 May 2004

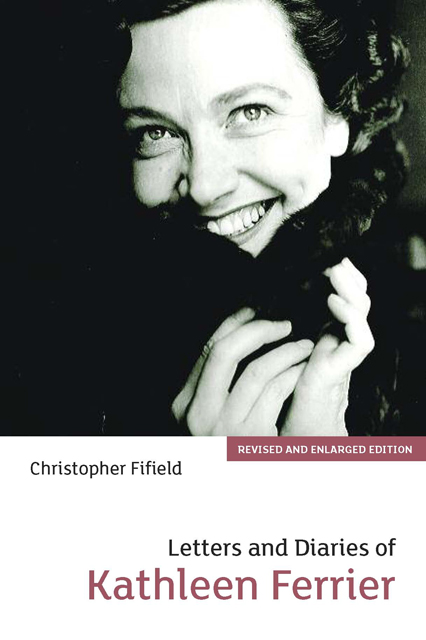

Letters and Diaries of Kathleen Ferrier

- Revised and Enlarged Edition

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 21 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 07 January 2004

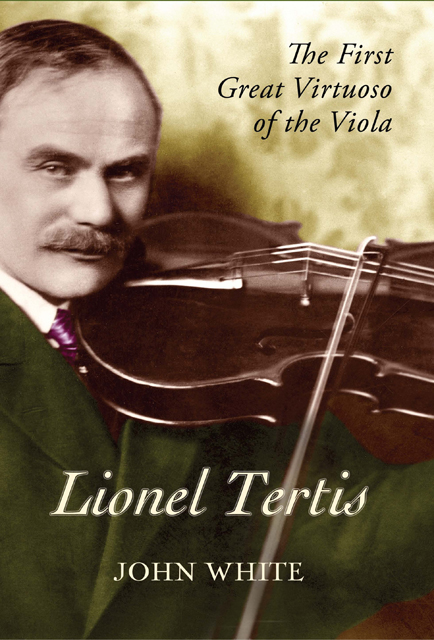

Lionel Tertis

- The First Great Virtuoso of the Viola

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 18 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2006

Lectures on Musical Life

- William Sterndale Bennett

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 18 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2006

Wagner and Wagnerism in Nineteenth-Century Sweden, Finland, and the Baltic Provinces

- Reception, Enthusiasm, Cult

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 17 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 18 November 2005

Music as Social and Cultural Practice

- Essays in Honour of Reinhard Strohm

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 10 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 July 2007

The Pursuit of High Culture

- John Ella and Chamber Music in Victorian London

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 10 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 November 2007

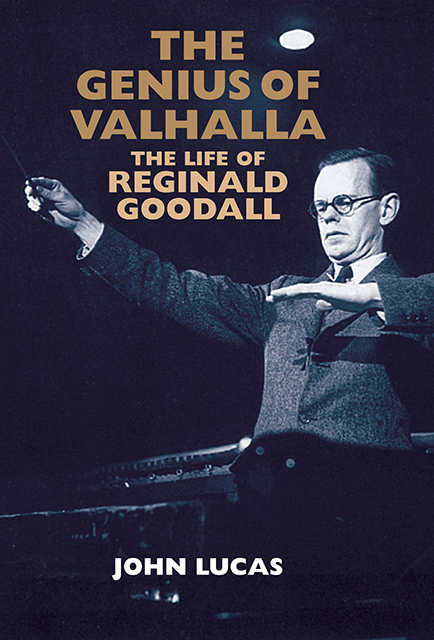

The Genius of Valhalla

- The Life of Reginald Goodall

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 07 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 October 2009

Benjamin Britten

- New Perspectives on His Life and Work

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 03 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 November 2009

Essays on the History of English Music in Honour of John Caldwell

- Sources, Style, Performance, Historiography

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 April 2010

Genetic Criticism and the Creative Process

- Essays from Music, Literature, and Theater

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 December 2009

Richard Wagner and the Centrality of Love

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 18 March 2010

The Consort Music of William Lawes, 1602-1645

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 01 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 July 2010

A Tanner's Worth of Tune

- Rediscovering the Post-War British Musical

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 01 March 2023

- Print publication:

- 17 June 2010

Art and Ideology in European Opera

- Essays in Honour of Julian Rushton

-

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 28 February 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 October 2010