Refine search

Actions for selected content:

15418 results in Military history

Naval Chronology

- Or, an Historical Summary of Naval and Maritime Events from the Time of the Romans, to the Treaty of Peace 1802

-

- Published online:

- 05 June 2015

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2015

The Chinese and their Rebellions

- Viewed in Connection with their National Philosophy, Ethics, Legislation, and Administration

-

- Published online:

- 05 June 2015

- Print publication:

- 01 January 2015

- First published in:

- 1856

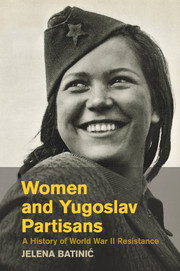

Women and Yugoslav Partisans

- A History of World War II Resistance

-

- Published online:

- 05 June 2015

- Print publication:

- 12 May 2015

Directions for Sailing to and from the East Indies, China, New Holland, Cape of Good Hope, and the Interjacent Ports

- Compiled Chiefly from Original Journals at the East India House

-

- Published online:

- 05 June 2015

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2014

Naval Chronology

- Or, an Historical Summary of Naval and Maritime Events from the Time of the Romans, to the Treaty of Peace 1802

-

- Published online:

- 05 June 2015

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2015

Naval Chronology

- Or, an Historical Summary of Naval and Maritime Events from the Time of the Romans, to the Treaty of Peace 1802

-

- Published online:

- 05 June 2015

- Print publication:

- 29 January 2015

3 - The Faithful in Arms

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 244-316

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chronology

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp xix-xxiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 689-704

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 591-600

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Religion, War and Morality

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 511-590

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 1-46

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 601-656

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

List of Illustrations

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp xvii-xviii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Religion and American Military Culture

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 138-243

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Note on Spelling

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp xvi-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Global Encounters

-

- Book:

- God and Uncle Sam

- Published by:

- Boydell & Brewer

- Published online:

- 02 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 May 2015, pp 396-510

-

- Chapter

- Export citation