Refine search

Actions for selected content:

15418 results in Military history

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp x-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Home Fronts, 1914–16

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 149-178

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 439-442

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Military Politics of the Contemporary Arab World

- Published online:

- 16 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - The War at Sea, 1915–18

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 209-234

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The July Crisis, 1914

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 35-58

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Online essay illustrations

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp viii-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Deepening Stalemate

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 115-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The European War UnfoldsAugust–December 1914

-

- Book:

- World War One

- Published online:

- 08 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 29 October 2020, pp 59-90

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

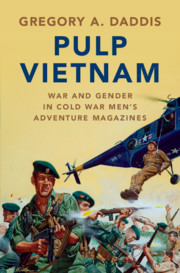

Pulp Vietnam

- War and Gender in Cold War Men's Adventure Magazines

-

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020

Chapter 2 - My Father’s War: The Allure of World War II and Korea

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 65-97

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - The Imagined “Savage” Woman

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 98-132

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp ix-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Macho Pulp and the American Cold War Man

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 28-64

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Notes

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 239-334

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: Warrior Heroes and Sexual Conquerors

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 1-27

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Plate Section (PDF Only)

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 335-348

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - The Vietnamese Reality

-

- Book:

- Pulp Vietnam

- Published online:

- 22 October 2020

- Print publication:

- 22 October 2020, pp 133-173

-

- Chapter

- Export citation