Refine search

Actions for selected content:

15401 results in Military history

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 495-541

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp v-v

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part III - The Unknown Soldier

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 323-404

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - De-Sacralisation Discourses

- from Part II - The Emperor’s New Clothes

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 245-322

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Monarchy and the Armistice

- from Part III - The Unknown Soldier

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 325-360

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 1-19

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 542-576

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Monarchy’s Role in Sacralising Post-War Commemoration

- from Part III - The Unknown Soldier

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp 361-404

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp vi-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Table

-

- Book:

- For King and Country

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021, pp ix-ix

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

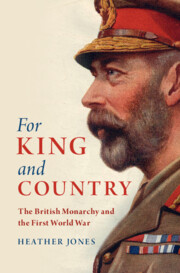

For King and Country

- The British Monarchy and the First World War

-

- Published online:

- 09 September 2021

- Print publication:

- 23 September 2021

3 - Small Wars and Domain Theory

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp 149-192

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp 437-446

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp xxiii-xxiv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp 368-372

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Bibliography

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp 425-436

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - The Masters of War Theory and Strategy

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp 52-148

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The Unified War Theory

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp 193-308

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp viii-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- The New Art of War

- Published online:

- 12 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 02 September 2021, pp xi-xxii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation