Refine search

Actions for selected content:

3430 results in Popular science

Index

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 197-202

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - The paranormal

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 38-63

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - Skepticism, ethics and survival

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 140-163

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Bringing skepticism down to earth

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 111-139

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Skepticism beyond the paranormal

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 164-185

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp ix-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Skepticism – from Socrates to Hume

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 64-85

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction: The paranormal and why it matters

-

- Book:

- Beyond Belief

- Published online:

- 05 April 2010

- Print publication:

- 20 October 2009, pp 1-11

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Hardwired Behavior

- What Neuroscience Reveals about Morality

-

- Published online:

- 13 October 2009

- Print publication:

- 19 September 2005

Labour, Science and Technology in France, 1500–1620

-

- Published online:

- 01 October 2009

- Print publication:

- 07 December 1995

Grape vs. Grain

- A Historical, Technological, and Social Comparison of Wine and Beer

-

- Published online:

- 16 September 2009

- Print publication:

- 10 March 2008

Charles Darwin's 'The Life of Erasmus Darwin'

-

- Published online:

- 26 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 10 October 2002

Real Science

- What it Is and What it Means

-

- Published online:

- 24 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 27 April 2000

The Golem at Large

- What You Should Know about Technology

-

- Published online:

- 19 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 02 May 2002

Future Imperfect

- Technology and Freedom in an Uncertain World

-

- Published online:

- 18 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 21 July 2008

Uncertain Science ... Uncertain World

-

- Published online:

- 11 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2003

Figments of Reality

- The Evolution of the Curious Mind

-

- Published online:

- 11 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 28 July 1997

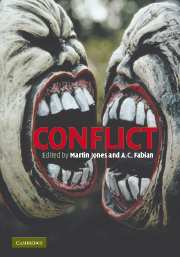

Conflict

-

- Published online:

- 11 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 12 January 2006

Power

-

- Published online:

- 07 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 12 January 2006

17 - The Last Lethal Disease

-

- Book:

- Future Imperfect

- Published online:

- 18 August 2009

- Print publication:

- 21 July 2008, pp 249-259

-

- Chapter

- Export citation