9.1 Introduction

Since the 1974 Carnation Revolution and subsequent processes of democratization and Europeanization, Portugal – together with Spain and Greece – embarked on a course of state- and nation building along common European trajectories, which included European Union (EU) accession, the buildup of a welfare state regime, and the introduction of comprehensive environmental policy (Kickert, Reference Kickert2011; OECD, 2001). This has meant a pronounced expansion in policy stocks in both policy fields under study (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019), which initially had been met with considerable expansion of administrative capacities for implementation. However, this development soon subsided and stagnated due to economic and fiscal pressures (Sotiropoulos, Reference Sotiropoulos2015; Teles, Reference Teles, Jann and Bouckaert2020). The mismatch between administrative capacities and policy accumulation has resulted in a scenario of increasing bureaucratic overload within implementation bodies. Consequently, policy triage has become a frequent and severe issue characterizing the execution of both social and environmental policies. Policy triage is thus endemic in both policy sectors under analysis and prevalent within virtually all public sector organizations.

The reasons for this gloomy picture – which characterizes Portugal as the country in our sample where implementation problems are the greatest – can be found in the various theoretical mechanisms that influence overload vulnerability and the internal commitment to overload compensation. With regard to overload vulnerability, a striking feature of the Portuguese arrangements is that although implementation is largely in the hands of central agencies, multiple opportunities for policymakers exist to attribute the political blame for implementation failure to the competent administrative bodies. Similar (and even more pronounced than in the case of Italy, see Chapter 8) blame is shifted between central agencies and their regional branches as well as between the Ministry of Finance and the sectoral ministries. In a similar vein, the governance arrangements guiding sectoral resource allocation provide implementation bodies with very limited leverage to mobilize additional resources in exchange for growing burden loads. This constellation of high-overload vulnerability comes with relatively weak commitment on the side of the implementation organizations to internally compensate accumulation-induced overload. Due to chronic underfunding, understaffing, and lack of organizational flexibility, overall policy advocacy and perception of policy ownership remains low, although for environmental implementing bodies, there are limited instances of overload compensation.

The case of Portugal hence shows that – contrary to the other countries under study such as Ireland (see Chapter 7) – the status of implementation bodies as an independent, central-level agency need not imply that overload-induced policy triage is a less likely scenario. Moreover, we also find that policy triage is a frequent and severe phenomenon even in constellations where implementation failures are highly salient, that is, in particular, regarding social policy issues.

In the following, we first provide a structural overview of environmental and social policy implementation in Portugal (Section 9.2). In Section 9.3, we present empirical evidence of the patterns of policy triage that characterizes implementation processes in both sectors under study. Sections 9.4 and 9.5 concentrate on the different mechanisms of overload vulnerability and overload compensation to shed further light on the reasons of widespread and severe policy triage for each of the two sectors under study. Section 9.6 summarizes our findings and draws general theoretical conclusions.

9.2 Structural Overview: Environmental and Social Policy Implementation in Portugal

Portugal constitutes an advanced Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) democracy, ranking highly on overall state capacity in a global perspective but ranking lower within our sample countries, below Denmark, Germany, Ireland, and the UK, but above Italy (Hanson & Sigman, Reference Hanson and Sigman2021). According to the worldwide governance indicators on government effectiveness, regulatory quality, or corruption, a similar pattern can be observed, with Portugal ranking below the other countries under study with the exception of Italy (Kaufmann et al., Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi2007, Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi2010).

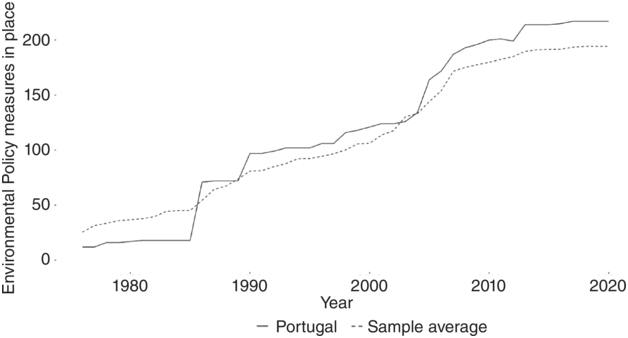

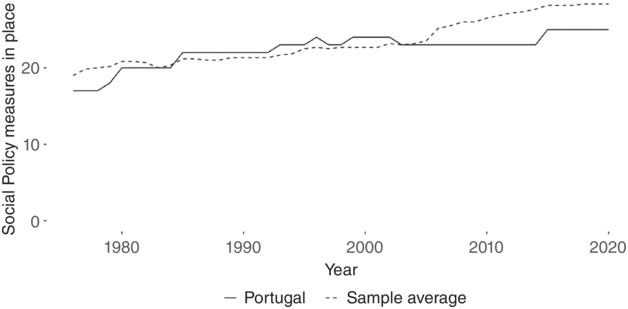

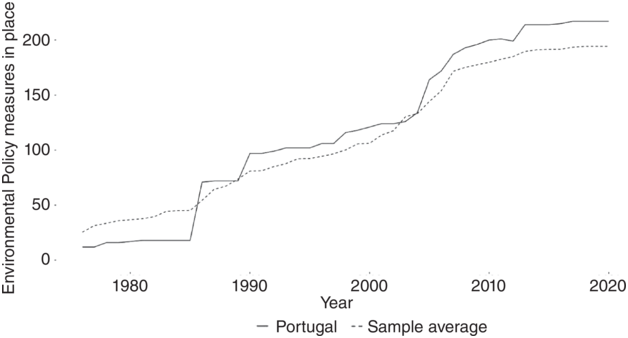

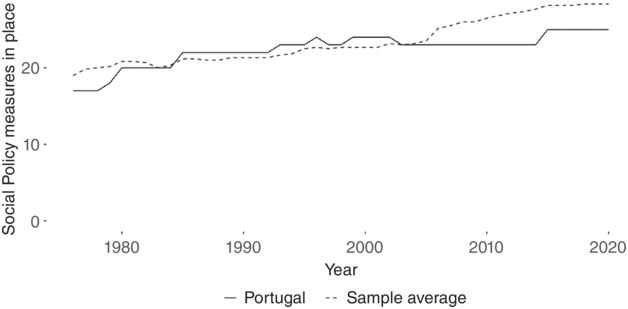

In marked contrast to this relatively low level of administrative capacity and governmental effectiveness, Portugal’s environmental sector exhibits a highly dynamic policy growth pattern that is comparable to Ireland’s (see Figure 9.1). However, unlike Ireland’s, Portugal’s policy growth has consistently remained above the sample average since the mid-1990s (Adam et al., Reference Adam, Knill and Fernández-i-Marín2017, Reference Adam, Hurka, Knill and Steinebach2019). In the social sector, policy growth follows a more restrained trajectory, closely aligning with the average development observed within our sample.

Figure 9.1 Environmental policy measures in Portugal.

Initially, the expansion of policy stocks in both sectors was accompanied by a growth in public expenditure, as rudimentary environmental and social policy frameworks were developed in line with modern European trajectories following democratization and accession to the EU (Ahrens, Reference Ahrens1998; Bronchi, Reference Bronchi2003; Campbell, Reference Campbell1990; OECD, 2001). However, as we will discuss in Section 9.3, this pattern sharply changed from the early 2000s onwards. While policy growth in both sectors continued, it was no longer matched by a corresponding expansion in the capacities required for policy implementation (Lourenço, Reference Lourenço2023: 7).

Portugal is characterized by a highly centralized public administration, rooted in the Napoleonic administrative tradition of state governance (Ongaro, Reference Ongaro, Painter and Peters2010; Peters, Reference Peters2008). Competences for policy formulation are concentrated at the central level (OECD, 2020a), with limited devolution of decision-making authority to subnational actors. Despite a constitutional mandate for decentralization and regionalization introduced following the 1974 Revolution, attempts to implement these reforms have repeatedly failed (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher1999). As a result, meaningful autonomy exists only in the island territories of the Azores and Madeira, which operate with a higher degree of self-governance than subnational entities in mainland Portugal.

In line with Portugal’s centralized approach, policy implementation is predominantly managed by central authorities and their regional branches. Decentralized administrative jurisdictions operate under a model of “fictional decentralization,” where power is delegated to deconcentrated intermediate-level bodies of the central government rather than to genuinely autonomous local authorities (Abrantes, Reference Abrantes2019; Teles, Reference Teles2016). As a result, the implementation of both environmental and social policies is firmly in the hands of central government agencies and their regional branches.

On the mainland, the local level maintains a system of districts, counties, and parishes that traces its roots back to the Estado Novo regime, albeit with democratized structures (Opello, Reference Opello1992). However, these local authorities possess limited fiscal and legislative autonomy in practice (Madureira, Reference Madureira2018; Nunes Silva, Reference Nunes Silva, Nunes Silva and Buček2017; Opello, Reference Opello1992), with most administrative personnel allocated to the central public administration and its regional offices (Magone, Reference Magone2011).

9.2.1 Competence and Burden Allocation in Environmental Policy

Environmental policymaking in Portugal is highly centralized and Europeanized. The Portuguese Constitution (Art. 9) established fundamental tasks concerning environmental protection and conservation, yet it was only after EU accession in 1986 that a modern environmental legislative framework developed. Portugal’s accession to the EU marked a turning point in its environmental policy. As a member of the EU, Portugal had to align its environmental laws and policies with European standards and directives, leading to the creation of more structured and coordinated institutions for environmental governance. During the 1980s and 1990s, a range of environmental agencies were established, including the creation of a dedicated Ministry of the Environment in 1990 (Queirós, Reference Queirós2002). From the 2010s onwards, this initial institutional structure underwent a series of reforms aimed at enhancing the formulation and implementation of Portuguese environmental policy. These reforms were largely driven by the need to comply with an expanding body of EU legislation, which imposed stricter regulatory standards and implementation requirements on member states (OECD, 2011). Most notably, these reforms led to the consolidation of previously fragmented inspection competencies within the independent General Inspection of Agriculture, Sea, Environment and Spatial Planning (Inspeção-Geral da Agricultura, do Mar, do Ambiente e do Ordenamento do Território; IGAMAOT) and the establishment of the Portuguese Environment Agency (Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente; APA) in 2007.

In 2012, the APA merged with the Institute of Water, the five Hydrographic Regional Administrations (Administrações Regionais Hidrográficas; ARHs), the Climate Change Commission, the Waste Management Monitoring Commission, and the Environmental Emergency Planning Commission. As a result of the merger, the APA plays a central role in the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of nearly all environmental policies but nature conservation. Describing itself as the state agency whose mission is the integrated management of environmental and sustainability policies, the APA is widely regarded as the country’s principal environmental administration.Footnote 1

Chiefly, the organization is tasked with monitoring of air and water quality regulations and adjacent laboratory and reporting duties. On those issues, the APA works in tandem with the five Regional Coordination and Development Commissions (Comissãos de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional; CCDRs), which have a broad regional mandate including coordinating and implementing regional development policies, territorial planning, and environmental affairs (CCDR, 2022). With regard to the latter, the CCDRs collect and monitor punctual measurement stations of the air quality network in their jurisdiction, while the data are ultimately shared with and processed by the APA (POR03). The APA also monitors large installations, and, together with the CCDRs, is responsible for environmental impact assessments (EIAs) of various kinds. Additionally, the APA via its deconcentrated river basin district administrations – the ARHs – also monitors water quality and is responsible for water management. This includes tasks such as measuring water quality, laboratory work, prevention of erosion, and reporting and documenting information. Another major part of the workload of the APA (and the CCDRs) is the issuance of licenses and permits for construction and controlling requirements and compliance thereof. The APA also is concerned with the issuance of invoices to users and polluters of water bodies according to national legislation (POR05). In summary, the overall workload is centralized in the hands of the APA, whereas the CCDRs as regional entities only act in a complementary manner and are dependent on the APA.

Another vital agency in the Portuguese environmental realm is the IGAMAOT, which bundles tasks of major inspection and enforcement activities into a single independent body. Unlike the APA, which operates under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment, IGAMAOT is managed in conjunction with the Ministry of Economy, the Ministry of Territorial Cohesion, and the Ministry of Agriculture. Primarily an inspection agency, IGAMAOT has centralized all the important implementation tasks concerning enforcement and compliance with environmental legislation. The main tasks of the organizations are inspections of industrial facilities and plants concerning industrial emissions and discharges, ensuring compliance with technical regulations, as well as reporting and monitoring duties. IGAMAOT also controls for hazardous substances and noise control, in addition to air and water pollution and follows up on individual or company complaints. The organization thus serves in the function of a “criminal police body in matters of environmental inspection” (POR01).

Moreover, the Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests (Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas; ICNF) manages Portuguese forests and nature reserves. Created in 2012 by merging the National Forestry Authority (Autoridade Florestal Nacional; AFN) with the Institute for Nature Conservation and Biodiversity (Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e Biodiversidade; ICNB), the goal was to establish unified responsibilities for nature conservation and forestry policy (Pinho, Reference Pinho2018). Yet, while the merger aimed to streamline coordination and improve implementation performance, they did not appear to result in significant personnel or operational changes (POR15).

ICNF plays a crucial role in licensing, controlling, and managing (economic) activities in forests, nature reserves, and other protected areas. The agency is jointly supervised by the ministries of the environment and agriculture as its tasks touch on both environmental protection and economic activities in forests and national parks. Previous iterations of the state forestry agencies in the twentieth century were managed under the Ministry of Agriculture and played an important role in the local and forestry industry – a role that gradually changed into a model of forest management, indirect state intervention, and forest protection after European Economic Community (EEC) accession and the merger of various state agencies into the ICNF over time (Pinho, Reference Pinho2018).

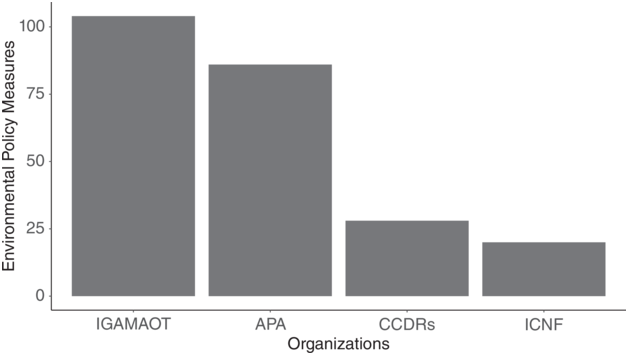

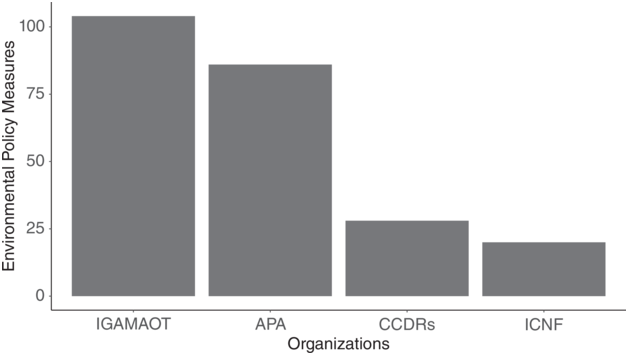

Lastly, as far as municipalities and parishes are concerned, they are characterized by a low level of adoption of environmental management practices and often lack awareness and knowledge with regard to environmental protection. This is in line with the broader responsibilities these lower tier levels of government have and the fact that central agencies and their deconcentrated units like the APA or the CCDRs are in charge of the large part of environmental policies (Nogueiro & Ramos, Reference Nogueiro and Ramos2009). Thus, in summary, the major implementing bodies in the Portuguese environmental sector are APA, IGAMOT, and ICNF (see Figure 9.2). Regional entities such as the CCDRs assist the APA in some environmental implementation tasks. The subsectors of clean air and water protection policies are in the hands of the APA and the IGAMAOT, while the ICNF’s jurisdiction covers forestry management, wildfires, and nature conservation. Figure 9.3 provides an overview of how the implementation load is distributed across organizations in the Portuguese environmental sector.

Figure 9.2 Social policy measures in Portugal.

Figure 9.3 Environmental policy measures per organization.

9.2.2 Competence and Burden Allocation in Social Policy

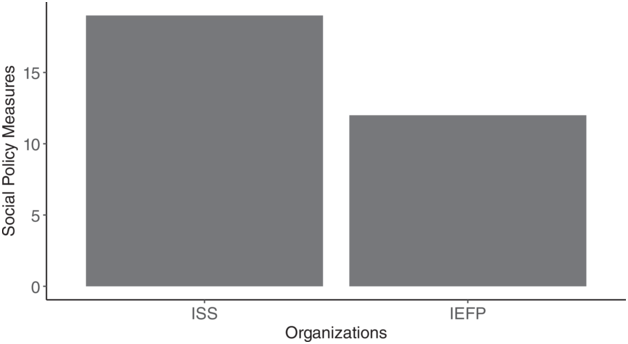

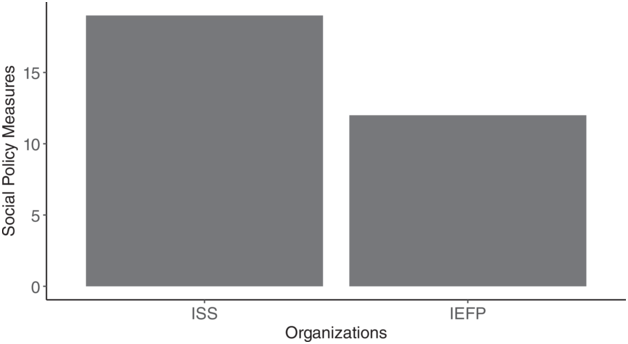

The allocation of policymaking and implementation competencies in social policy follows a pattern similar to that observed for the environmental sector. The implementation of social policies is carried out by two independent agencies at the central level and their regional branch offices, while the local authorities are only tasked with subsidiary functions of minor impact (see Figure 9.4). The two major implementation bodies are the Institute of Social Security (Instituto da Segurança Social; ISS) and the Institute of Employment and Vocational Training (Instituto do Emprego e Formação Profissional; IEFP).

Figure 9.4 Social policy measures per organization.

The ISS became operational in 2001, marking a significant shift toward centralizing the implementation of social security policies within a single organization. The organization incorporates the National Pension Center (Centro Nacional de Pensões; CNP) and eighteen district social security centers (ISS, 2021), consolidating administrative functions that were previously managed in a decentralized manner by several regional social security centers. This centralization was intended to streamline operations, improve efficiency, and ensure greater uniformity in the administration of social security policies across Portugal (ISS, 2021). Chiefly, the ISS implements benefit payments in all major areas of social policy, including the payments concerning pensions via the CNP, the payments of the various childcare benefits for children and new parents, as well as the payment and control of unemployment benefits for those out of work. The autonomous island territories of the Azores and Madeira operate their own social security institutes that are only formally attached to the mainland institution.

In addition to the ISS, the IEFP and its regional employment centers are critical institutions in Portugal’s labor market, responsible for job placement, vocational training schemes, and job creation programs. Established in 1979 to consolidate employment and training policies, the IEFP is the result of a merger between the Workforce Development Fund (Fundo de Desenvolvimento da Mão-de-Obra; FND), previously responsible for the development and protection of the active workforce on the one hand, and the National Employment Service (Serviço Nacional de Emprego; SNE), which was tasked with facilitating the reintegration of the unemployed into the labor market, on the other.

To deliver its services, the IEFP operates through a decentralized network that includes five regional delegations and fifty-four employment and vocational training centers.Footnote 2 IEFP tasks range from consulting and job placements to efforts in creating self-employment and entrepreneurship, controlling eligibility and feasibility of such schemes, and operations and paying out benefits. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the IEFP was also responsible for distributing government funds to struggling firms and entrepreneurs aimed at the preservation of jobs (POR06).

9.3 Patterns of Policy Triage: A Frequent and Severe Phenomenon in Both Sectors

In Section 9.2, we have seen that both sectors under study were subject to policy growth with particularly pronounced expansion in the environmental domain. This growth has translated into a significant increase in implementation tasks for the responsible authorities. While the initial expansion of policies was accompanied by parallel increases in administrative capacities (Bronchi, Reference Bronchi2003), a growing gap between burdens and administrative emerged from the 2000s onwards (see also Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher & Steinebach, Reference Fernández-i-Marín, Knill, Steinbacher and Steinebach2024: 1249). This development renders policy triage a highly frequent and severe phenomenon in the implementation of both social and environmental policy.

9.3.1 Policy Triage in the Environmental Sector

When it comes to the implementation of environmental policy, triage is highly prevalent, both in terms of frequency and severity. The implementing bodies clearly feel the ever-growing tension between strongly increasing burdens resulting from a growing stock of regulations and guidelines and their limited capacities to respond to these challenges. In addition, environmental law – reliant mostly on EU transpositions – is still not fully codified, which renders implementation tasks additionally complex and challenging as concrete regulatory guidance is lacking (POR09).

All implementing agencies report dramatic increases in the mismatch between growing implementation burdens and available administrative capacities. This imbalance has led to frequent and, in some cases, severe patterns of organizational policy triage. While implementing bodies, particularly central national agencies, retain some capacity to rationalize and establish prioritization schemes (POR01), this ability is limited to fulfilling only the most critical tasks. Prioritization is driven either by public interest or through risk assessments, leaving less urgent tasks unaddressed (POR09; POR11; POR05).

For IGAMAOT, the overload is so severe that inspection activities are rationed through a “quality over quantity” approach (POR01; POR08). Delays in implementation tasks are an omnipresent phenomenon, even for those tasks that are strongly prioritized, like inspection reports: “The priority is the inspection reports. That is actually the most important objective. If we have to decide between several things, the inspection reports always get prioritized” (POR09). Yet, “the reports resulting from our inspection actions that sometimes should take a month or two months to be prepared […] end up extending and sometimes exceeding four months” (POR01).

The overload at some units has reached an extent that, at times, forces the managerial staff to also care for workloads unrelated to their administrative-managerial job, as noted by senior CCDR staff: “There comes a time when it has to be me and the other two managers who step up and do technical work, make up for the lack of people” (POR03). On occasion, it is reported that extensions have to be solicited – even at ministry requests (POR03). Policy triage has become a regular feature within the organization, even with the most vital tasks of environmental inspection. As an implementer puts it, “30 inspectors are unable to provide ideal coverage […]” (POR09).

Likewise, policy triage is a pervasive and severe phenomenon at the APA, characterized by selective implementation to manage overwhelming workloads. A regional director at the APA confirms that their units respond to the overload “by prioritizing […] those tasks that have a deadline that if we fail to meet implies a tacit approval. […]. These must not fail” (POR14). As a result, tasks and complaints without legal deadlines or immediate consequences are systematically delayed. This approach to prioritization, driven by strict adherence to legal deadlines, is echoed at both the local level (POR03) and across managerial and street-level roles (POR15; POR14). The emphasis on meeting legal deadlines often outweighs intraorganizational efforts to streamline workloads, such as risk analysis schemes (POR08). For instance, while laboratory responses are regularly delayed, exceptions are made for vital cases, such as those mandated by the Bathing Water Directive (POR13).

Yet, despite prioritization, staffers consistently report that strong overburdening implies that tasks are not only postponed but not fulfilled at all. As one staff member at the APA reported, that “[…] often we are so overwhelmed that we don’t have time to reflect, to study new initiatives, new movements, new strategies and we tend to fall into a bureaucratic routine, despite that concern to do things well, and as quickly as possible. (…) there are things that remain to be done, with unfortunate consequences, that we regret but cannot do much about” (POR05).

The workload at the laboratories of the APA has become so overwhelming that they are no longer able to process the large volume of samples they receive. This has resulted in increased inaccuracies in assessments and regulatory outputs, with decisions often based on incorrect and flawed measures (POR15). Furthermore, crucial tasks such as monitoring and inspection, essential for effective environmental governance, are increasingly neglected and left unfulfilled due to the sheer volume of work:

We need to safeguard that things are going well in the field. And this is very much lacking in the environmental area: going there to see if things are going well.

Another staff member further elaborated on the conundrum the APA faces due its lack of oversight capacities:

What is most problematic, in my view, is being unable to monitor and inspect. I think that the inspection would be a very important task, because we are often faced with situations, that if they were referenced in a timely manner there wouldn’t be so many infractions, so many irregular situations.

APA staff openly acknowledge that they do not always succeed in fulfilling their organizational mandate with the resources they are provided with. In fact, it is surprising that negative consequences of implementation failures are not more severe:

This work overload is such that actually it is almost a miracle that there are no more failures. We do some control here and try to create control mechanisms so that there are no failures. But, in short, there are some things that remain to be done or that are not done as they should be done, with some prior reflection, with some previous debate, that we end up not having time to do.

Yet, severe implementation failures do happen, and it is often only in these cases that higher awareness of overload problems can be observed:

Unfortunately, only when things fall and the problems really emerge, we see some positive change. Facing a problem, we do not try to prevent it, find methods to deal with it, and provide enough resources to prevent it from resurfacing or solving it. Unfortunately, that’s not what happens.

Triage is also a prominent feature in the organizational routines of the ICNF characterized by prioritization and delays of essential tasks. Conflicting policy goals of balancing environmental conservation with economic interests like agriculture, tourism, and urban development complicate decision-making processes and contribute to delays. Additionally, the high burden loads resulting from the complex policies and rules ICNF is tasked with implementing further strain its limited capacity, making triage an unavoidable and recurring pattern in its operations.

We have to deal with an increasing volume and complexity of tasks. (…) Yet, human resources in public administration were never a priority of the governments. (…) We don’t have the resources to read and interpret them, because it’s not just about receiving directives, it’s not just about receiving regulations, it’s about knowing how to interpret them. Often these are published and we are not even given time to discuss it. We will then have to implement measures that were decided by others and that we did not have time to study, to study them so that we can implement them rigorously. We may, not on purpose, of course, but we may make mistakes in a decision we are taking precisely because we do not have a thorough knowledge of all the regulations we have in Portugal. In terms of regulation, it has become a complete exaggeration. We have an enormous burden of regulation.

In addition, the agency is struggling with seasonal peaks that periodically increase workloads and reshuffle prioritizations. Besides, forestry management and nature conservation, the ICNF also engages in activities that relate to forest fires, which are a common occurrence in Portugal. As a regional director puts it, “[…] forest fires are something that we have had a lot of. Our forest area has been very badly affected by fires. So that’s always a priority. I usually say that from October to April we’re a little calmer, but from May onwards we’re all on alert” (POR02). With rising temperatures due to the climate crisis, this special annually occurring overload can only be expected to become more and more severe, impacting adequate policy implementation and exacerbating existing problems (Gomes, Reference Gomes2006; Mateus & Fernandes, Reference Mateus, Fernandes and Reboredo2014).

In view of these overload problems, triage is a dominant pattern in ICNF’s organizational routines. One interview participant indicated, for instance, that to answer and process one request, “you have to leave another one pending. But, yes, it is a concern that we have, and we would be able to give a response in less time if we had more resources” (POR02). Lacking adequate capacities, the ICNF frequently struggles to fulfill tasks properly or promptly, leading to errors and oversights that are often detected only by chance. As one staff member explained: “We often have, imagine, within a decree, articles that have been revoked before and that we sometimes don’t realize. It’s only when we issue an opinion based on that decree that we realize it” (POR02).

In sum, the agencies responsible for the implementation of environmental policy in Portugal display high levels of policy triage. Triage is not only a frequent phenomenon but also partially entails severe consequences as essential tasks, such as inspections, monitoring, data analysis, or the consistent interpretation and specification of legal guidelines, are delayed or simply neglected. This assessment is also echoed by the Environmental Implementation Review of the European Commission, which emphasizes the need to equip Portuguese implementation bodies “with the knowledge, tools and capacity to improve the delivery of benefits from that legislation, and the governance of the enforcement process” (European Commission, 2022: 44).

9.3.2 Policy Triage in the Social Sector

When examining the implementation of social policy, we find levels of policy triage that are equally high as those observed in the environmental sector. For social implementers, triage is a routine occurrence, driven by overwhelming implementation burdens that far exceed the administrative capacities of the agencies involved. Similar to the environmental sector, this overload stems from significant increases in implementation demands – often driven by secondary legislation – that are not matched by a corresponding growth in administrative funding and personnel (POR12). In case of the ISS, these pressures are further exacerbated by drastic reductions in available resources (ISS, 2021). As a result, the two central implementers of Portugal’s social policy portfolio are frequently forced to prioritize tasks, delay others, or leave some unfulfilled altogether.

In case of the IEFP, triage becomes apparent by constant prioritization of tasks at the expense of secondary and voluntary work, which is often neglected. For instance, creating proximity to certain unemployed populations has been made difficult for the IEFP due to task constraints (POR06). When external events, such as forest fires or the COVID-19 pandemic, impose additional burdens, even the IEFP’s primary mission of job creation is overshadowed by the immediate need to preserve existing jobs, tying up funds and personnel (POR06). According to an IEFP civil servant, overburdening was particularly acute during the tumultuous period from 2012 to 2015 when unemployment surged and the agency’s workload tripled, creating an environment of permanent stress across the organization (POR07). As with environmental agencies, legal deadlines are prioritized, but, as is apparent, such triage measures cannot halt or reverse the rampant implementation deficits.

The overburdening of the IEFP and the resulting triage patterns significantly undermine implementation effectiveness. Overwhelmed by an excessive number of tasks and projects, the agency struggles to maintain the quality of its work. As one staff member noted:

We have deadlines and I personally do not believe that a given technician who has 150 projects to analyze, that the quality of their work is going to be the same if they give him 200 or 300. It is almost impossible not to verify a reduction in the quality of his work.

The challenges of overburdening at the IEFP are compounded by the lack of a structured or planned approach to prioritization. Decision-making on priorities often appears ad hoc and highly subjective. As one street-level implementer noted, “[t]here is no very objective criterion. What is there is the sensitivity of the technician to understand who is waiting for an answer [and] whether that answer can wait or not,” further noting how quickly priorities can shift over the course of a workday (POR12). This sentiment is echoed by other interviewees who describe how tasks deemed a priority – often subjectively – receive resources, but simultaneous competing priorities require teams to be reorganized, often involving weekend work to meet deadlines (POR07).

However, this approach not only places significant discretion and pressure on already overburdened civil servants but also leads to more severe cases of implementation failure. For instance, payments can sometimes be delayed by several months as implementers are forced to focus on other urgent tasks (POR12). Among street-level implementers, such delays are often carried out with the tacit approval of supervisors or managers and can therefore be viewed as a planned coping strategy, or a form of triage (POR10).

While the IEFP is pressured to respond to company clients in a timely manner, staff reports that:

to do a new thing we have to compromise others. These priorities that led us to massively reallocate resources obviously come to us from above, from the Board of Directors or directly from the Ministry. We also have our own planning, but it is constantly being modified by virtue of these priorities.

Turning to the ISS, a very similar pattern of implementation failures resulting from bureaucratic policy triage can be observed. The ISS has faced significant challenges in recent years, primarily stemming from administrative overload and a growing number of social welfare claims. Compounding these challenges, the agency’s workforce was more than halved over a decade. In 2005, the ISS employed nearly 15,500 staff members, but by 2015, this number had dropped to just 7,500 (ISS, 2021: 214). While the agency reported that some of these reductions were mitigated through the automation of processes and the digitalization of citizen services (ISS, 2021), these efficiency gains did not fully offset the loss of capacity caused by the steep reduction in staff.

One major consequence of this imbalance is significant delays and inefficiencies in processing claims, particularly for unemployment and family support benefits. These delays have been exacerbated by the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a surge in demand for social security services. There have also been complaints about difficulties in accessing information and support, with citizens often struggling to get through to call centers or receive timely updates on their claims. In view of these and other cases, the Ombudsman Maria Lúcia Amaral reported in 2022 that

a review of the procedures adopted by the services is imperative, with a view to avoiding the suspension of social benefits or their rejection, without prior investigation of the possible applicability of safeguard rules regarding the regularity of the permanence of citizens in national territory.Footnote 3

Another aspect is the strain on the staff of the ISS. The increased workload and the implementation of strict bureaucratic measures have left many workers overwhelmed, which, in turn, has affected the quality of service provided to the public. In response, ISS resorted to more standardized procedures that often came at the expense of case-based and problem-oriented handling of issues of social policy implementation as the administrative changes meant that thousands of people were being assigned to the same professional (Casquilho-Martins, Reference Casquilho-Martins2021). These strategies of the ISS to cope with overload have also been reflected in instances where foreign nationals faced unjust suspensions of benefits due to administrative errors or lack of awareness of updated policies. This issue has been particularly concerning in terms of social insertion programs for immigrants, where procedural mistakes have led to unjust denials of benefits.Footnote 4

Trade-offs of focusing addressing requests in a standardized rather than in an individual manner were accompanied by a selective orientation toward providing support merely in extreme situations rather than concentrating on the prevention of social needs and problems. Although these decisions sought to address the immediate effects of the crisis and austerity, in the medium and long term, they led to a regression of the achieved social development, capacity constraints, and poor working conditions (Casquilho-Martins, Reference Casquilho-Martins2021).

In sum, the implementation of social policy in Portugal is characterized by frequent and severe policy triage. Both the IEFP and the ISS face problems of administrative overburdening that mainly result from growing tasks and additionally aggravated by austerity challenges of the financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and – in the case of the ISS – in a drastic reduction of staff. Resource constraints and staffing shortages lead to delays in processing claims, errors in benefit distribution, and difficulties in responding to citizen inquiries. To manage, both agencies are forced to resort to triage frequently, prioritizing urgent cases and leaving less critical ones unattended for extended periods.

9.4 Environmental Policy: Organizational Triage Despite Proximity to the Center

In Section 9.3, we have shown that frequent and severe patterns of triage are present in all agencies that are involved in implementing Portuguese environmental policy. All agencies suffer from dramatic and growing mismatches between implementation burden and available capacities. Compared to the other countries under study, these findings are striking insofar as central-level agencies tend to be less affected by overload problems in most cases, with correspondingly lower needs for routinely resorting to trade-off practices, as their counterparts at the local level. For the latter, the greater “distance” from the center typically entailed a higher vulnerability of being overloaded. Moreover, in contrast to independent and often highly specialized agencies at the central level, local implementation bodies are typically structured around general organizational arrangements. Within these frameworks, the implementation of environmental or social policies is just one of many responsibilities, rather than a dedicated focus. In consequence, policy implementation by local authorities requires the balancing of potentially conflicting policy priorities (e.g., environmental versus economic concerns). This, in turn, might potentially undermine internal commitment to overload compensation – at least to a larger extent as this is the case for specialized and independent agencies. Yet, none of these arguments seems to hold for the implementation of Portuguese environmental policy, where central-level independent agencies are not only highly vulnerable to overload but also reveal limitations in their internal potential of overload compensation.

9.4.1 Blame Attribution for Implementation Failure: The Finance Ministry as the Joker

In Chapter 2, we argued that the political limitations to shift blame for implementation failures significantly influence policymakers’ incentives to allocate sufficient administrative resources to implementation agencies. The more directly the central government is responsible and accountable for effective implementation, the less vulnerable implementation agencies are to overloading. From this perspective, the status of the environmental implementation bodies as central-level agencies – with some, such as IGAMAOT, even located within the same building as their supervising ministry – should, in principle, reduce policymakers’ incentives to assign additional implementation tasks without providing corresponding capacity expansions.

This argumentation, however, overlooks that in the case of Portugal the allocation of blame for implementation failure is not so much a matter of the responsibilities of sectoral ministries and agencies, but essentially involves the Ministry of Finance as crucial blame-taker. Similar to the case of Italy, the quirks of the Napoleonic administrative system (centralized state revenues) and the fiscal pressures on the Portuguese state jointly privilege the Ministry of Finance in the realm of sectoral resource allocation over its fellow ministries. Chronically persistent budget deficits, combined with the effects of the recent economic and financial crisis, have created a pressure on all of the public administration, which hinders effective internalization by the sectoral formulator level under the guise of neoliberal fiscal responsibility (Di Mascio & Natalini, Reference Di Mascio and Natalini2015; Nishimura et al., Reference Nishimura, Moreira, Sousa and Au-Yong-Oliveira2021; Teles, Reference Teles2016; Theodoropoulou, Reference Theodoropoulou2015).

The fiscal structure of the Portuguese state offers ample opportunity for policy formulators to shift blame to the Finance Ministry or general fiscal constraints for lacking resources, funds, or personnel, allowing them to retain a generally good working relationship with most of the management level of the bureaucracy. Overall, the relationship between implementers and their supervisors, governing boards, and even the line ministries is described as responsive and cordial (POR09; POR02). Staff on the management level even highlighted that their direct superiors often demonstrate sensitivity and careful consideration of their respective needs and challenges (POR01; POR02; POR05). An APA member acknowledged that the Environment Ministry wants to help but is blocked by financial decisions (POR05). Other implementers take it more stoically, “[w]e complain. Normally they hear us, pat us on the back and say, ‘keep going!’” (POR14). The blame game is hence, to a lesser extent, played between the Environment Ministry and environmental agencies as between sectoral policymakers and implementers on the one hand, and the Ministry of Finance on the other. In other words, sectoral policymakers have to deal with the fiscal constraints of the state and can shift the blame for implementation problems onto that direction (CEMR, 2007).

9.4.2 Limited Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization

The central role of the Finance Ministry also implies that the opportunities of implementation bodies to mobilize additional resources are severely constrained. The fiscal structure of the Portuguese state influences and exacerbates the problems arising from the limited ability to mobilize resources externally. Here, the Portuguese bureaucracy is hampered by ingrained administrative traditions of centralized revenues streams and fund allocation (Torres, Reference Torres2004), which were even further strengthened by the consequences of the economic and financial crisis (Di Mascio & Natalini, Reference Di Mascio and Natalini2015). The implementing level is aware of this conundrum (POR05; POR14). Against this, successful rallying for additional implementation resources fails often or is relegated to limited gains only. Despite a good understanding between implementer and formulator level, vital matters of resource allocation, especially (permanent) staff, are hard to push through. As an APA bureaucrat states: “the Ministry of the Environment is very aware of the problems and interested in helping but due to financial decisions everything is blocked” (POR05). In this constellation, implementers also report that being too demanding would have counterproductive effects. Unlike in the past, the agency leaders “[…] don’t want to bother because they are afraid, they may be exchanged for another. […]. They know that if they upset too much, they will replace them with someone who doesn’t bother them” (POR11). In other words, the formulator level has “domesticated” the management level of the public agencies.

In view of these limitations, interviewees from all agencies emphasize problems of over-aging within their units and the public administration at large. Following many decades of stagnation under the Salazar regime (Corte-Real, Reference Corte-Real2018), the public sector experienced high levels of growth in personnel and resources (funding) as the Portuguese state caught up with the rest of the advanced OECD democracies via increasing public expenditure (Bronchi, Reference Bronchi2003). During this time of democratization and modernization, some opportunity for resource mobilization existed and appeared welcome at the top levels of government. However, starting with the early 2000s, the Portuguese state has not been able to adequately allocate staff, relying instead on the increasingly older, experienced bureaucrats to take on the increases in implementation tasks. The budgetary constraints following the economic and financial crisis have only served to lock in this development. New hires have become rarer.

Yet, this state of affairs poses a problem, as “older people retire, new hires do not replace them in the same number. They’re not enough” (POR15). This inability to replace staff with new human resources has the detrimental side effect of public organizations “cannibalizing” each other for their personnel needs via internal transfer. This can also lead to some misallocations; bureaucrats at the highly overloaded IGAMAOT complain that the lack of a duty of permanence with the inspectorate allows for (overworked) inspectors to “go to another organization where it is less demanding, and which requires a lower workload” (POR01). This is also reported by workers away from the managerial level (POR09).

Additionally, due to extant laws and stipulations, external mobilization of resources even for problem-solving of cases is delayed or prohibited. An APA public servant describes a case where a

[…] dam of the water reservoir that supplies water to my region is flooded with water inside the structure. We need to pump out the water. The pumps are broken. We estimate the cost to pump the water as 300 euros. The APA is blocked from subcontract[ing] externally, so we do not have those 300 euros. But […] we collected 3 million euros in revenues last year in our region, which went straight to the public treasures, to the Ministry of Finance. So, this is the real world.

Such situations are undoubtedly very frustrating for implementers. The Ministry of Finance frequently acts as a bottleneck, withholding even basic funding for the maintenance of vital systems, such as pumps or monitoring stations, despite these funds being theoretically allocated (POR05).

The regional managers also notice the problems they face with mobilizing additional resources, especially when confronted with the bureaucratic hierarchy in place.

We have no direct communication. There is always a hierarchy that communicates. We place a request which goes through various instances of the hierarchy. Our requests are not questioned because our direct headship is aware of the problems. But then, based on the delay with which we have the answer, I can deduce that there is no such sensitivity [at the top].

APA staff describes how difficult it is to get new staff, reporting how the agency may have to wait one or two years before they are able to hire someone new. Bureaucratic delays must be overcome by a lot of goodwill on the side of superiors (POR15).

Very rare instances of new hiring often depend on the personal charisma or networking talent of the heads of the implementers (POR03). Lacking the authorization to recruit externally, CCDRs, APA, and their regional ARHs essentially have to “steal” people from each other (POR03) to keep operations going (POR09; POR01). An IGAMOT street-level worker reports this development, “[w]hen I joined in 2004, we were 30 inspectors. And in 2021 we still are 30. Why? People come in and out. Some people can’t stand this. Some are still resistant, but we have colleagues who tell me that they left, and they have a completely different quality of life” (POR09). So, while all public entities face this problem, the IGAMAOT has been hit by this development the hardest because of the nature and complexity of its inspection tasks which staff have described as “[…] a brutal workload” (POR09).

Yet, staff mobility across agencies has ambivalent effects for agencies trying to solve their overload problems by raising additional resources (POR09; POR01). The ability of the staff to move within the different sectoral organizations allows the various units to fill in gaps in implementation capacities, compensating for a lack of new staff or specialization, and tackling their expanding workloads. Thus, even if budget constraints from above force the bureaucracy to downgrade personnel, internal transfers can mitigate workloads for individual units or entire organizations by mobilizing the resources of their fellows within the sector. For example, the APA reported that their unit gained a biologist through internal transfer – the first biologist since 2004 – which allowed them to analyze samples that previously were sent to the central APA at Lisbon (POR13). Yet, managerial staff with the ICNF stresses that despite the positives (the unit being able to recruit adequate staff and do their work), the internal flexibility of the civil service often serves as a way to “steal technicians from other entities” who are and should normally be considered partners (POR02). Overall, this state of affairs ends up being a zero-sum game that strains intraorganizational relations and that can, in the case of the IGAMAOT, hurt policy implementation severly.

9.4.3 Limited Commitment to Overload Compensation

Contrary to the Italian case where implementation bodies are still able to compensate high overload by internal efforts at least partially, the prospects for such patterns are much more limited for the Portuguese implementation bodies in which both the perception of policy ownership and policy advocacy are undermined by various factors.

The lacking sense of policy ownership mainly results from fundamental resource limitations. On the one hand, the agencies display a strong esprit de corps. Most staff have an engineering or natural sciences background and are brought up within the entirety of the environmental public administration, typically following a career path through many different postings from forestry management to local air pollution control, to inspection activities at industry plants, and back. An IGAMOT inspector points out, for instance, that “[a] very good thing we have is the exceptional work environment between colleagues, that is exceptional, really exceptional. They are very collaborative, they help each other a lot, they support each other. There is a very good team spirit” (POR09).

On the other hand, perceptions of policy ownership are undermined by various factors. First, overload led to changes in the perception of work as becoming less about quality and more about quantity, leaving a staffer with the feeling “that my work is currently not impacting […] or improving the environment” (POR09). This essentially means a deviation from the “quality over quantity” approach. While this is also reflected in the work spirit of the street level (POR09; POR11), there is a perception that the work done is de facto developing into a “working for numbers, for quantitative targets” situation (POR09).

Policy ownership is further undermined by the problem of over-aging staff. In the APA, the problem of over-aging combined with overwork has led to cases of work fatigue and prolonged medical leave, which compromises the ability of the agency to compensate overload with its present staff (POR13). Lacking replacement of retiring staff further hampers policy ownership due to a loss of expertise. One implementer of a regional authority fears the retention of knowledge in jeopardy with many experienced civil servants nearing retirement age and “no new head[s] to work on these issues” (POR04). A lab technician at the APA links the high average age in the organization (fifty-five years) to their unit being understaffed; once “older people retire, new hires do not replace them in the same number. They’re not enough” (POR15). Among the organizations, only the IGAMAOT seems to be unaffected by this issue. Here, the problem seems to be a higher turnover rate and less so over-aging.

This is aggravated by the fact that oftentimes, bad or old equipment hampers staff to effectively implement policy. In other words, lacking resources means worse equipment and less effective overload compensation, like an equipment malfunction leading to failure to adequately conduct monitoring and analysis (POR13).

Further limitations emerge from lacking policy advocacy, which is undermined by underdeveloped policy communication and coordination within and between the different implementation bodies. The environmental agencies still face many communication problems that hamper effective compensation, as a bureaucrat at IGAMAOT points out, even the inspectors within a team of thirty do not fully know what the others are doing and that vital things about their own agency are found out externally, not from within the organization (POR11; POR03; POR08).

In view of these challenges, internal attempts of overload compensation have so far been restricted to improving the collaboration between the different implementation agencies from bottom-up. In this arrangement, IGAMAOT takes on the major industrial and polluting facilities and offers backup for the smaller scale situations delegated to other entities (POR09; POR01). The APA has started to pawn off some tasks to the long-neglected municipal level in order to be able to cope with the workload. The APA has established protocols with municipalities, and they act under APA supervision. This makes the municipal level take on a complementary role in helping the APA central agency (POR14). Informally, bureaucrats request aid from each other across units in order to circumvent the more complicated way of formal requests (POR03).

In addition, the internal mobility within the public administration is used by individual agencies to strengthen the capacity to compensate overload. The flexibility in internal transfers has the advantage of spreading initiative and experience around, helping prevent stagnation and rigidity within units (POR04). Yet, as already emphasized in Section 9.4.2, internal mobility can turn problematic over time due to the interaction of over-aging and hiring stops. Once an experienced civil servant retires, their position is oftentimes not filled by external hiring, but by internal transfer, depriving another unit or entity of a technician, specialist, or administrator (POR14). In other words, over-aging, and the resulting susceptibility to sickness and rigidity, decreases the capacity of internal overload compensation while hiring stops showcase the inability to mobilize additional resources externally. In the end, the only opportunity for the mobilization of additional staff environmental organization seems to be to turn to each other for staff.

9.5 Social Policy: Organizational Triage Despite Direct Implications of Implementation Failures

The fact that social implementation bodies display similar levels of high policy triage as their environmental counterparts is even more striking at first glance. The finding of high triage within independent agencies at the central level not only deviates from the typical patterns found for the other countries under study (where the center mostly does better than the local level). It also deviates from our overall finding that triage in the social policy implementation is generally less pronounced as in the environmental field. Given that implementation failures are directly felt by the welfare recipients, there is a higher likelihood that policymakers are held accountable by the public. Accordingly, policymakers face more limitations for blame-shifting and have higher incentives to provide implementation bodies with sufficient resources. In the following, we will take a closer look at the question why this scenario is not observed for the social policy implementation in Portugal.

9.5.1 Blame Attribution for Implementation Failure: Agencies as Scapegoats

Contrary to the environmental field, political blame for social policy implementation failures is not only shifted to the Ministry of Finance but also to the agencies in charge of implementation. It seems that paradoxically the high political salience of social policy implementation provides incentives for politicians to deflect the responsibilities for problems to the agencies. The main reason for this can be seen in the highly unpopular welfare cuts the government had to undertake in the aftermath of the financial crisis (Caldas, Reference Caldas2012; Pedroso, Reference Pedroso2014; Pereirinha & Murteira, Reference Pereirinha, Murteira, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016). While the government was mainly held responsible for these reforms, politicians had strong incentives to shift blame for the implementation of these policies to other actors, hence shifting attention from the adoption of unpopular policies to the implementation of these measures. In fact, this way the highly salient and politicized nature of social policy allowed the government to shift blame to the implementing bodies.

IEFP personnel state that the formulator level tends to commit the agency to tasks with inadequate means, resulting in public blame being labeled on the agency if it predictably underperforms – a situation only growing more poignant with rising politicization (POR07; POR12). As an implementer in the unemployment sector asserts,

[t]he Employment Institute has always been an organization, I would say, politicized. We deal with a factor of government assessment that has its weight, which is unemployment rates and the ability to solve labor needs on the part of the economy, on the one hand. Therefore, if companies are unable to find staff, it is the Employment Institute that they will blame, or the government and then the Employment Institute, or vice versa, this is connected. […] We have always been, an organization, I would say, that is politically instrumentalized.

A regional director seconds, “[…] if we do anything and we fail, it immediately appears in the newspaper and in the media, and sometimes very much overstating what happened. And oftentimes with misleading ideas about what is going on” (POR07). This highlights also how deeply reputational concerns are at the forefront of the minds within the IEFP. With the IEFP, implementation deficits and resulting triage are often conceptualized in terms of creating a bad reputation in their area of operation and with clients (POR12). An implementer of the IEFP reports that the organization is also careful to monitor client satisfaction (POR10).

In addition to this, the social policy bodies exhibit a lack of sensibility on the part of the top-level officials when organizational matters are neither sufficiently nor adequately resolved even if not involving matters of resources (POR12). This is in stark contrast to the environmental top-level officials, who strive to maintain and successfully uphold relationships with their implementers. Within the social policy field, implementers often feel reduced to mere tools by policymakers, solely tasked with enforcing regulations (POR06; POR07; POR12). For the IEFP, many of the programs they manage demand ongoing accountability, placing the responsibility for their success or failure squarely on their shoulders (POR06).

9.5.2 Limited Opportunities for External Resource Mobilization

Paralleling the environmental sector, the Napoleonic state administration with its centralized revenues and funds (Torres, Reference Torres2004) prevents adequate external resource mobilization by the social implementation agencies. This limitation is even more severe than in the environmental sector as agencies lack informal access to policymakers. Stricter adherence to hierarchy hampers the street-level implementers in mobilizing resources. As a result, even if immediate supervisors or directorates are sympathetic to street-level concerns, complaints, and needs, initiatives at reform or mobilization get lost on their way to the higher levels where actual decision-making on such matters occurs. This situation is felt on the street level and perceived to be detrimental to their general work situation (POR12). Additionally, retrenchment and austerity policies following the economic and financial crisis has put the social policy sector under particular fiscal pressures (Caldas, Reference Caldas2012; Pedroso, Reference Pedroso2014; Pereirinha & Murteira, Reference Pereirinha, Murteira, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016), which also affects the provision of administrative capacities in the longer term, with one implementer remarking that “[…] the economic crisis justifies what has been done from then on. The crisis has already been overcome, there has already been a moment of economic growth, of recovery, and in Portugal it is even a significant one […]” (POR12).

Similar to the environmental field, the lack of resources has fueled competition for personnel between the different agencies. Yet, also in the social sector, such internal transfers are seen as problematic since public entities can effectively take civil servants from each other (POR06). An IEFP regional manager describes internal mobility even “[as] redesigned in a pernicious way that makes it too easy for people to move between jobs, which creates plunder within the different public services, even with the values of respect for others” (POR07).

9.5.3 Limited Commitment to Overload Compensation

While both ISS and IEFP display very high overload vulnerability, the prospect of compensating overload by agency-internal efforts is gloomier than for the environmental agencies. This can be traced to two factors. Firstly, policy advocacy, which is already relatively weak for environmental agencies, is further hindered by the absence of informal communication channels between social agencies and their supervising ministries. Second, the social agencies lack a common esprit de corps and display higher heterogeneity in terms of professional backgrounds of staff who often feel instrumentalized and politicized (POR06; POR07). Overall, these factors imply that ISS and IEFP – despite the high salience of social policy implementation – display very low internal commitment toward overload compensation. Like the environmental field, this situation is aggravated by the aging and scarcity of staff.

The fact that fresh hiring is not done in adequate numbers means that older, long-serving bureaucrats must take on the increasing workloads of the agencies. Over time, this situation decreases the capacities for agencies to compensate adequately. Increasing absenteeism due to health-related problems and subsequent medical leave have already been noted as a problem at the IEFP (POR10). Moreover, decrease in flexibility of staff affects the efficiency of operations in both agencies: “The increase in the average age leads to higher resistance to change, not everybody adheres as well” (POR07). Further, in the Employment Institute, a regional director misses “a coherent distribution of workers across the different age groups,” raising concerns about work fatigue and the operational challenges this imbalance creates within the bureaucracy (POR06; POR07). The implementer level seems largely resigned to their plights and continues to work with what they have (POR12). An exception to this is internal training plans within the IEFP that develop new skills for its employees. “We train in vast areas, both technical and behavioral, and I must say that I think there has never been so much training” (POR06).

Despite these challenges, the agencies try to punctually compensate for overload by staff working overtime. At the IEFP, a street-level bureaucrat reports that

[p]eople sacrifice themselves and stay another hour, an hour and a half, a few more hours, to solve something that is really urgent and that should not be left for the next day. What can wait is pushed, until the moment when you can’t push anymore and then the person has to stay another two hours to do what should have [been] done by now.

It also happens that staff are forced to take work with them over the weekends and finish it at home (POR07). From the managerial standpoint, this state of affairs enables them to still cope with their primary implementation tasks (POR07; POR06). On the street level, impressions are less optimistic. The increasing workload and harsher work rhythm at the IEFP have caused newcomers to the agency to quit after some time, leaving the agency with less manpower (POR07).

Low levels of organizational policy ownership are also reflected in lacking initiative for internal reforms or rationalization processes (POR12). Highly formalized and hierarchical decision-making imply that already minor efforts to streamline the organizations are doomed to fail. For example, even a simple voicemail system or the introduction of new software is mishandled, to the chagrin of the implementers (POR12). It is also mentioned that there are still many information systems that need to be harmonized (POR10). Regarding rationalization processes, it appears that direct supervisors or the board of directors are initially receptive to bottom-up proposals. However, these proposals often get lost within the organizational structure (POR07; POR12).

9.6 Conclusion

The example of Portugal provides compelling evidence in favor of the theoretical insights presented in Chapter 2. Implementation agencies within social and environmental policy sectors are highly susceptible to being swamped by the growth of sectoral policies (see Table 9.1). Politicians, motivated by incentives to create policies, encounter few obstacles when assigning blame for implementation failures to other stakeholders. Meanwhile, the implementation authorities themselves face numerous challenges in acquiring additional resources. Austerity measures, such as not filling in positions left vacant by retiring staff, have resulted in decreased personnel capacity and a decline in expertise.

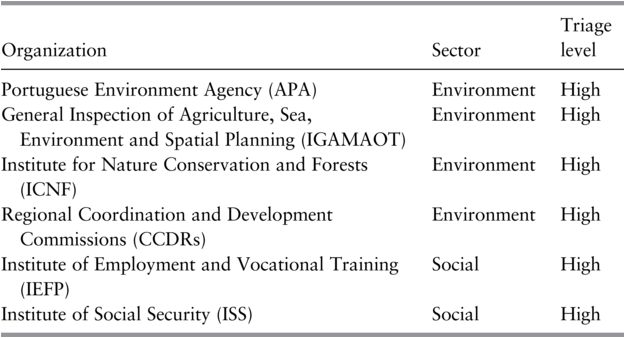

| Organization | Sector | Triage level |

|---|---|---|

| Portuguese Environment Agency (APA) | Environment | High |

| General Inspection of Agriculture, Sea, Environment and Spatial Planning (IGAMAOT) | Environment | High |

| Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests (ICNF) | Environment | High |

| Regional Coordination and Development Commissions (CCDRs) | Environment | High |

| Institute of Employment and Vocational Training (IEFP) | Social | High |

| Institute of Social Security (ISS) | Social | High |

Sectoral organizations have demonstrated only limited efforts to manage overload. Strategies such as working overtime and reallocating staff between sectoral agencies have provided only limited relief from the pressures, barely mitigating the need for policy triage. Consequently, triage routines have become more prevalent and a regular practice in Portugal compared to the other countries analyzed. In many cases, trade-off decisions have led to more severe consequences, such as neglecting specific tasks like emission monitoring due to resource constraints. In view of these problems, the overall effectiveness of policy implementation is rather weak, given the pressures of policy overproduction and declining bureaucratic capacities. There are evident limits to the ability to compensate for overload. A further worsening of policy triage – in terms of both frequency and severity – can be expected if there is no push toward more resource allocation and (permanent) personnel for the tasks and policies given to implementing bodies.

The case of Portugal diverges from the observed patterns in the other countries in our sample in two analytically intriguing ways. First, the case shows that independent agencies at the central level can also display high vulnerability to overload. Second, the Portuguese case shows that even if implementation problems are highly politically salient – as it is typically the case for the social sector – this does not help to avoid high levels of policy triage. In scenarios involving unpopular policy reforms, such as austerity-driven welfare cuts, policymakers seem increasingly inclined to characterize these contentious policy adoptions as implementation failures, thereby deflecting political blame.