Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Ends of First Sf: Pioneers as Veterans

- 2 After the New Wave: After Science Fiction?

- 3 Beyond Apollo: Space Fictions after the Moon Landing

- 4 Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- 5 The Rise of Fantasy: Swords and Planets

- 6 Home of the Extraterrestrial Brothers: Race and African American Science Fiction

- 7 Alien Invaders: Vietnam and the Counterculture

- 8 This Septic Isle: Post-Imperial Melancholy

- 9 Foul Contagion Spread: Ecology and Environmentalism

- 10 Female Counter-Literature: Feminism

- 11 Strange Bedfellows: Gay Liberation

- 12 Saving the Family? Children's Fiction

- 13 Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- 14 Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- 15 Towers of Babel: The Architecture of Sf

- 16 Ruptures: Metafiction and Postmodernism

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

14 - Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1 The Ends of First Sf: Pioneers as Veterans

- 2 After the New Wave: After Science Fiction?

- 3 Beyond Apollo: Space Fictions after the Moon Landing

- 4 Big Dumb Objects: Science Fiction as Self-Parody

- 5 The Rise of Fantasy: Swords and Planets

- 6 Home of the Extraterrestrial Brothers: Race and African American Science Fiction

- 7 Alien Invaders: Vietnam and the Counterculture

- 8 This Septic Isle: Post-Imperial Melancholy

- 9 Foul Contagion Spread: Ecology and Environmentalism

- 10 Female Counter-Literature: Feminism

- 11 Strange Bedfellows: Gay Liberation

- 12 Saving the Family? Children's Fiction

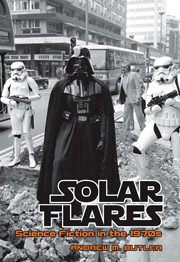

- 13 Eating the Audience: Blockbusters

- 14 Chariots of the Gods: Pseudoscience and Parental Fears

- 15 Towers of Babel: The Architecture of Sf

- 16 Ruptures: Metafiction and Postmodernism

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Michael Bond's ‘A Spoonful of Paddington’ (1974) begins with Paddington Bear conducting an experiment to see if he can bend spoons. An episode of the BBC children's programme Blue Peter had featured Uri Geller, then famous for dowsing, for starting or stopping timepieces using psycho kinetic powers (which he claimed derived from aliens) and for bending spoons by lightly rubbing them with his thumb. Paddington, typically, is a mix of copycat and sceptic, so conducts experiments with various substances to see if these will soften metal to allow it to bend. Scientists and magicians alike were disputing Geller's claims; Paddington copies Geller's feat only to discover that he is using a set of spoons with trick hinges. There was still an appetite for belief in pseudoscience and the paranormal over the rational explanation, and much sf of the 1970s catered for this audience's sense of wonder, from the belief that humanity had been uplifted by aliens to sf that had much in common with supernatural horror and expressed anxiety about paternal, maternal and filial feelings. This can be seen in the pseudoarchaeology books by Erich von Däniken, Robin Collyns and Charles Berlitz, which were disputed by authors such as John Sladek, but fed into the blockbuster Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977), novels by Richard Cowper and television series such as The Omega Factor (13 June–15 August 1979) and Quatermass (24 October–14 November 1979), sometimes with a degree of scepticism.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Solar FlaresScience Fiction in the 1970s, pp. 192 - 205Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2012