Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Chapter 12 The Legacy of Gold

- Chapter 13 The Story of Sterkfontein Since 1895

- Chapter 14 The South African War of 1899–1902 in the ‘Cradle of Humankind’

- Chapter 15 White South Africa's ‘Weak Sons’: Poor Whites and the Hartbeespoort Dam

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Chapter 12 - The Legacy of Gold

from PART 5 - Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Chapter 12 The Legacy of Gold

- Chapter 13 The Story of Sterkfontein Since 1895

- Chapter 14 The South African War of 1899–1902 in the ‘Cradle of Humankind’

- Chapter 15 White South Africa's ‘Weak Sons’: Poor Whites and the Hartbeespoort Dam

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Summary

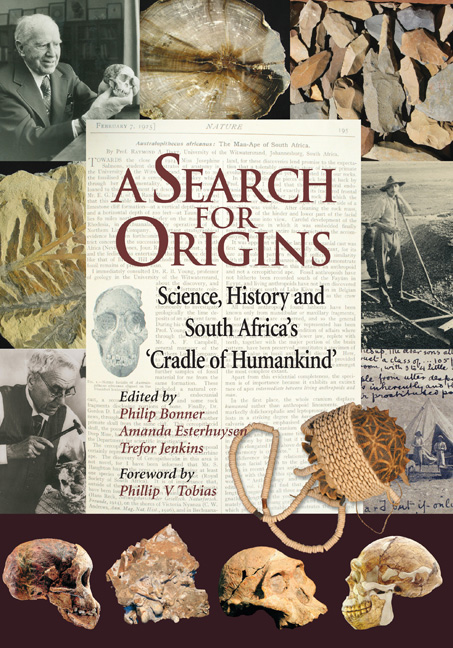

Gold explains why South Africa was the site of the first early hominid fossil discoveries in Africa. Gold also explains why South African palaeontologists have been at the forefront of palaeontological research ever since the discovery of the Taung skull by Raymond Dart in 1924.

Gold changed the face of South Africa. The massive reserves of gold uncovered on the Witwatersrand in the 1880s and 1890s led to the South African War of 1899–1902, and the construction of a modernised, centralised South African state. The economic dynamo of gold likewise transformed South Africa into the most developed economy on the continent of Africa. Finally, the discovery of gold gave South Africa's scientific community a massive intellectual transfusion, vastly expanding the scale of geological research in the country, and prompting at one remove the birth of the science of palaeontology. Without gold the incredibly rich fossil heritage of Sterkfontein, Swartkrans and Kromdraai would have taken far longer to be discovered, and probably longer still to be apprehended. This chapter traces the story of the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand area, and more specifically in the area now known as the ‘Cradle of Humankind’, and the subsequent union of science and gold in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Scientific exploration in nineteenth-century South Africa

A number of scientific explorers ventured into the interior of South Africa in the early to mid-nineteenth century, probably because the substantial port town of Cape Town offered an ideal springboard for such expeditions. Andrew Smith, whose exploratory activities in the region have been discussed in Chapter 11, was one of the first travellers to record the ruins of the immense Tswana cities on the doorstep of the Cradle area, in 1832; he did so while engaged in a geological and fossil-hunting expedition, and his route seems to have taken him within a short distance of the Sterkfontein deposits. At more or less the same time hunters and would-be colonists were fanning out through the interior of southern Africa, as described in Chapter 11. One such adventurous individual, by the name of Karel Kruger, claimed to have discovered gold ore somewhere along the Witwatersrand in 1834, and took samples back to the Cape.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Search for OriginsScience, History and South Africa's ‘Cradle of Humankind’, pp. 206 - 215Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2007