Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

PART 4 - Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 31 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Map

- Foreword

- PART 1 Introduction: Africa is Seldom What It Seems

- PART 2 Introduction: Fossils and Genes: A New Anthropology of Evolution

- PART 3 Introduction: The Emerging Stone Age

- PART 4 Introduction: The Myth of the Vacant Land

- PART 5 Introduction: The Racial Paradox: Sterkfontein, Smuts and Segregation

- Epilogue: Voice of Politics, Voice of Science: Politics and Science After 1945

- Notes, references and recommended reading

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Index

Summary

Over the past 1 500 years the Magaliesberg mountains and the Cradle's western border have been host to some of the most densely settled African societies in South Africa. The Cradle fringe boasted both the first Early Iron Age settlement identified in South Africa (dating to around 350 AD) and one of the largest Sotho/Tswana cities which was constructed there in the mid-1700s. Gazing out from the visitors’ centre at Maropeng, the eye thus traverses several major sites of early African civilisation and the horizon hides several more. From the early nineteenth century on, African societies and this deep history of African occupation experienced a double obliteration: the first one physical, the second intellectual. The chapters in this section attempt to explain the process by which this occurred.

During the twentieth century most of the interior of South Africa was parcelled out in white farms.White children in white South African schools were taught that this was entirely legitimate, and these claims were justified on the basis of the myth of the empty land. This myth fell into two parts. School texts recorded that the first black South African agricultural communities to immigrate into South Africa crossed the Limpopo River, the subsequent state's northern border, at more or less the same time that van Riebeeck set foot in and colonised the Western Cape in 1652 (Theal cited in Cobbing 1984). Neither Africans nor Europeans, therefore, could assert a prior claim on the land. More sympathetic academic reconstructions based on African oral traditions could only push the date of indigenous colonisation of the interior back two to three hundred years, which scarcely constituted much of a prior right.Most studies, moreover, depicted African societies as being in a state of repeated migration and movement. Like the thinly settled predecessor populations of San and Khoi, therefore, they could not be seen as taming or settling particular tracts of land.

Even these residual assertions were, moreover, entirely extinguished by the accepted depiction of the period of internecine conflict known as the difaqane or mfecane which immediately preceded the intrusion of the colonial frontier in the form of the Great Trek of 1838.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

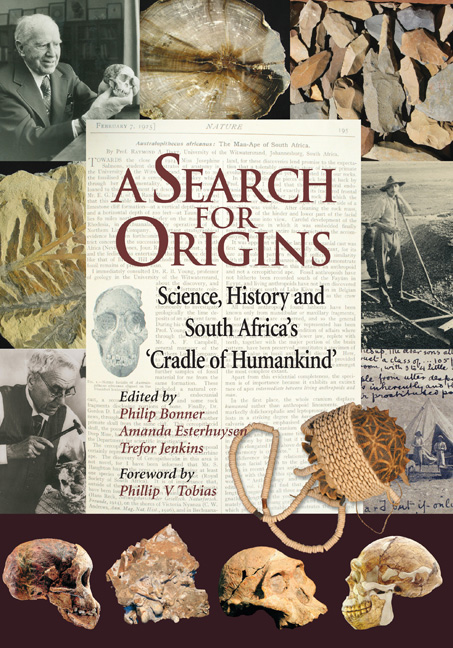

- Information

- A Search for OriginsScience, History and South Africa's ‘Cradle of Humankind’, pp. 141 - 147Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2007