This case is difficult because Clark’s statement –“I think I would like to talk to a lawyer”– reflects at least a tentative decision in favor of having a lawyer. It does not, however, indicate unequivocally that a final decision has been made.

Nonthreatening attempts to persuade the suspect to reconsider that initial decision are not, without more, enough to render a change of heart the product of anything other than the suspect’s free will. Thus, what is most remarkable about the Miranda decision–and what made it unacceptable as a matter of straightforward constitutional interpretation in the Marbury tradition–is its palpable hostility toward the act of confession per se, rather than toward what the Constitution abhors, compelled confession … The Constitution is not, unlike the Miranda majority, offended by a criminal’s commendable qualm of conscience or fortunate fit of stupidity.

In the United States, police interrogators are often trained to prioritize getting a custodial suspect’s statements (Reference Inbau, Reid, Buckley and JayneInbau et al., 2001). What maximizes a police interrogator’s strategy is to get incriminating statements from suspects. Now, the law requires that statements be voluntary, knowing, and freely provided, hence police interrogators must read suspects the Miranda rights prior to the onset of custodial interrogation and may not overtly or coercively get suspects to waive them. This chapter challenges the notion that custodial suspects freely and voluntarily waive their Miranda rights. In a police interrogation, perception and preference, such as invoking or not invoking the right to counsel, are subject to manipulation. Manipulation is the process by which an interrogator may alter a custodial suspect’s preferences for the benefit of the interrogator.

This chapter provides the theoretical framework for suspects’ invocations for counsel in the corpus. The analysis will focus on the discursive features of suspects’ invocations for counsel during custodial interrogation, as well as the sequences of talk that follow the suspects’ invocations, including the police interrogators’ use of requests for clarification. This part of the analysis will apply game theory, specifically hypergame theory (Reference BennettBennett, 1980), to describe police-suspect exchanges after a custodial suspect invokes counsel. This is a novel approach to analyzing institutional discourse and, in particular, police interrogations.

4.1 Invoking Counsel: A Constitutional Right Handicapped by the Law

There is a presumption in the law that suspects who wish the assistance of counsel must invoke so unequivocally. This creates a distinction between a valid invocation for counsel, that is, one that can stop an interrogation, and an ambiguous one that may not prompt such action from the police. The validity of the invocation is, for the most part, dependent on the police’s assessment of the invocation. Hence, police interrogators may end an interrogation at any point when the suspect invokes their rights, albeit directly or indirectly – with indirectly formulated invocations being the most common and least successful at invoking rights (see Reference MasonMason, 2013, Reference Mason, Mason and Rock2020). The manner in which police approach the invocation of rights stage of an interrogation is often guided by the law and training, and strategically framed, rather than by discursive frameworks.

4.1.1 Invocations As a Type of Speech Act

Reference Grice, Cole and MorganGrice’s (1975) theory of conversational implicature examines how speakers convey illocutionary force that the hearers recognize. For Grice, understanding how people mean more than they say is integral to understanding how indirect (nonliteral) meaning is communicated. He proposed the principle of conversational implicature: “make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged” (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, p. 45). When speakers abide by this principle, their utterances are of a suitable length (quantity), truthful (quality), clear (manner), and relevant (relation). Speakers, however, do not always abide by these maxims of conversation. If a speaker says at the dinner table, “Can you pass me the salt?,” the addressee assumes that the speaker is being relevant, and, thus, has an ulterior motive for not being direct. The violation of one or more of the conversational maxims, such as the maxim of relation in the above example, thus serves as a trigger for the addressee to search for an implied or indirect meaning: its intended perlocutionary effect.

How addressees process and respond to an indirect speech act also lies with the means in which the act is performed. Reference HoltgravesHoltgraves (2002), for example, remarks that there are conventional and nonconventionalFootnote 1 means of performing a speech act: “a conventional means for performing a speech act means that the literal meaning of the utterance is pro forma, not to be taken seriously” (p. 32). An example of this type of pro forma utterance in a legal context is “Can I get a lawyer?,” or, in the form of an assertion, “I need a lawyer.”

Research on conventional indirect requests suggests that people tend to recognize their meaning in a direct fashion, without the need for a time-consuming inference process (i.e., the idiomatic approach to comprehension). In a conversational exchange, addressees appear to disregard the direct meaning of a speaker’s indirect request (see Reference GibbsGibbs, 1983; Reference HoltgravesHoltgraves, 1994; Reference Holtgraves and AshleyHoltgraves & Ashley, 2001; Reference JaszczoltJaszczolt, 2019). Thus, the assumption that literal meaning primarily, or alone, plays an important role in the comprehension of conventional indirect requests is not widely supported by psycholinguistic evidence (see Reference Gibbs, Buchalter, Moise and FarrarGibbs et al., 1993; Reference GibbsGibbs, 1999; Reference HoltgravesHoltgraves, 2002, Reference Holtgraves, Katz and Colston2005). This finding is particularly relevant for invocations for counsel, since judges in our corpus have ruled that conventional invocations for counsel may be equivocal or unequivocal. Excerpt 4.1 shows an example of a conventional invocation for counsel treated as equivocal by the police interrogators, but ruled as unequivocal by the court.

1 Suspect: Can I get an attorney right now, man?

2 Officer 1: Pardon me?

3 Suspect: You can have attorney right now?

4 Officer 1: Ah, you can have one appointed for you, yes.

5 Suspect: Well, like right now you got one?

6 Officer 1: We don’t have one here, no. There’s not one present now.

7 Officer 2: There will be one appointed to you at the arraignment, ah, whether you can afford one. If you can’t one will be appointed to you by the court.

8 Suspect: All right.

9 Officer 1: [Inaudible].

10 Suspect: I’ll – I’ll talk to you guys.

In Excerpt 4.1, the police officer (Officer 1) requests clarification of the suspect’s invocation for counsel – “Can I get an attorney right now, man?” – using a follow-up question “Pardon me?” The police officer seems to either not have heard the utterance correctly or not understood its intent. The latter hints at the possible ambiguity of the suspect’s request. The suspect responds to the officer’s request for clarification with “You can have attorney right now?” to which the officer responds with “Ah, you can have one appointed for you, yes.” The next turns of talk show the suspect asking again for an attorney – “Well, like right now you got one?” – followed by the officer’s response “We don’t have one here, no. There’s not one present now.” In these exchanges, the officer’s requests for clarification and follow-up moves are not used to address the apparent ambiguity of the request, as for example to verify what the suspect is actually requesting (see Reference NohNoh, 1998, Reference Noh2001; Reference BlakemoreBlakemore, 1994; Reference MasonMason, 2016, Reference Mason, Mason and Rock2020), but to establish that the initial invocation was equivocal/ambiguous and it does not rise to the legal standard of unequivocalness needed to cease an interrogation. In the excerpt, the police officer has taken the stance that the suspect was not requesting counsel but rather was inquiring about the availability of counsel at the police station. The next turns of talk serve to remind the suspect of his rights (Officer 2): “There will be one appointed to you at the arraignment, ah, whether you can afford one. If you can’t one will be appointed to you by the court.” This reminder would require that the suspect attempt to invoke counsel again, despite having been unsuccessful on multiple occasions, and/or inquire about the process to acquire an attorney during the arraignment. The suspect does not take these routes and proceeds to waive his rights and provide a statement to the police. In this case, the suspect’s requests for counsel were ruled unequivocal: “Alvarez’s repeated questions about the immediate availability of an attorney were a clear and unequivocal invocation of his Miranda right to counsel, and he did not thereafter waive that right” (Alvarez v. Gomez, 1999).

Directing a suspect’s invocation for counsel is also highlighted in Excerpt 4.2. In this excerpt, police officers use, among other tactics, requests for clarification to attempt to thwart the suspect’s invocations for counsel and get the suspect “back on track”.

1 Mande: And if you decide to answer questions now, without a lawyer present, you have the right to stop answering questions at any time.

2 Davis: If, if I’m, if I’m going to answer questions, I’m going to need a lawyer here.

3 Mande: Alright, well, this is just so you understand that … and then down here, it’s just now we’re, this is the part where, if you want a way to talk to us and answer questions, that’s where you sign there. If you don’t want to talk to us, don’t …

4 Davis: I want to talk to you, but I just need my lawyer.

5 Chaney: Ok, ok, so here’s what you’re telling us—you do want your lawyer?

6 Davis: I want to talk, yeah. But I need my lawyer present.

7 Chaney: We wanna … either you talk to us now … if you want to talk to us now, without anybody else present, you have to sign that waiver. If not, all bets are off, you go into the system, ok?

8 Davis: Yeah

The negotiations that occur in requests for clarification, as in Excerpt 4.2, are intended to establish a mutuality of understanding that cannot be fully achieved until the speaker’s intent is clear. Often these requests for clarification take the form of partial or full echo questions (see Reference Pöchhacker, Baraldi and GavioliPöchhacker, 2012) such as “you need a lawyer?” or “lawyer?” or as explicit or implicit confirmation (see Reference SchlangenSchlangen, 2004) such as “Did you say you need a lawyer?” or “a lawyer?” The request for clarification could also simply ask for specification, such as (referring to a lawyer) “a what”? As Reference SchlangenSchlangen (2004) explains: “What the questions in these examples have in common is that, unlike ‘normal’ questions, they are not about the state of the world in general, but rather about aspects of previous utterances: they indicate a problem with understanding that utterance, and they request repair of that problem” (p. 137). In the police interrogations that comprise the corpus, however, follow-ups that appear to be requests for clarification are often used to deter the suspects from being able to determine their best options. Asking the suspect a “loaded” follow-up request, such as “Ok, ok, so here’s what you’re telling us – you do want your lawyer?,” although may appear to request clarification, and many rulings in the corpus deem these as such, has an alternate purpose: to narrow the suspect’s options to either talk to the police officers or “all bets are off, you go into the system.” This is an important point, since the law gives police officers wide latitude to clarify and establish whether a suspect wants an attorney. In practice, as seen in the excerpts, this allows the police to insert their own objective into the interrogation and potentially manipulate the suspect into not wanting an attorney present (see Reference YunckerYuncker, 1995).

Asymmetry in police–suspect exchanges may also affect how suspects perceive police follow-ups and use indirectness to gauge their options during police interrogation. In conversational exchanges in which there is asymmetry of knowledge, indirectness may provide a socially conventional way of invoking counsel, albeit not necessarily an effective one. In the United States, police officers do not need to inform suspects of the reasons for their arrest.Footnote 2 Once suspects are read their Miranda rights, police officers may not be forthcoming either. Furthermore, legal rulings, such as Davis, facilitate police officers not informing suspects whether their invocations rise to an unequivocal standard. The suspects’ inability to recognize, at the onset of the police interrogation, whether being indirect is effective when invoking counsel, as it is in other discursive contexts, will sustain the asymmetry of knowledge between police officers and suspects, benefiting those conducting the interrogation.

4.1.2 Maintaining Asymmetry in Police Interrogations

In police interrogations, police officers control the direction of the interrogation, which limits the suspects’ ability to introduce topics, ask questions, or give directives. In these types of exchanges, power usually resides with the police officers because they are “vested with such authority by the institutions that employ them” (Reference Berk-SeligsonBerk-Seligson, 2009, p. 71). Police officers are often trained to implement their own linguistic agenda and dominate the agendas of the custodial suspect (e.g., Reid technique). In contexts of asymmetry, lay persons may show an aversion for directness (Reference Busse and FisiakBusse, 2002; Reference TerkourafiTerkourafi, 2011), resulting in the use of face management and politeness in the formulation of speech acts (Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown & Levinson, 1987; Reference GoffmanGoffman, 1959, Reference Goffman1967).

Face work (Reference GoffmanGoffman, 1967, p. 44) is the ritual attention people must give to each other in order to have self-regulating participants in social encounters. Social order is sustained through face work: by supporting one’s face the other’s face is also supported. Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson (1987) expand on Goffman’s theory and provide a linguistic realization of face called politeness theory. They argue that face is comprised of both negative face, or the desire for autonomy, and positive face, or the desire for connection with others. Like Goffman, Brown and Levinson argue that face is continuously subject to threat. For Brown and Levinson, many of the acts speakers perform in social interactions are inherently face threatening. Requests, for example, threaten negative face since they restrict an individual’s autonomy and freedom from interference. They may also threaten positive face if the request implies a criticism of the addressee which lessens solidarity between the interactants.

In general, all directives (e.g., requests) may threaten the speakers’ face and require a strategy that manages the effect of the threat to face on the conversational participants. Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson (1987) lay out this strategy in their theory of politeness. They argue that politeness strategies can be ordered in a continuum. The least polite strategy is bald on-record politeness. This strategy adheres to Grice’s maxims and is maximally efficient. An example of bald-on record politeness is the formulation of requests using the imperative (i.e., a direct speech act), such as “Get me an attorney” or “I want an attorney.” The other politeness strategies (in their ascending order of politeness) include: positive politeness (e.g., “Can you get me an attorney?”), negative politeness (e.g., “Can I get an attorney?”), and off-record politeness (e.g., “I think I need help here”). Of note, the most polite strategy, off-record politeness, is the prototype of indirect communication since the speech act is not conventional and must be inferred (e.g., a novel indirect request, hints, rhetorical questions, etc.).

In the corpus, a gamut of indirectly formulated invocations for counsel is observed. It is not uncommon for suspects to invoke counsel in a nonconventional manner. The law often tags these invocations as ambiguous or equivocal formulations aimed at gauging the police officers’ responses (a type of pre-invocation). Most lay persons (e.g., suspects), however, may not know that invocations for counsel must be formulated directly and “unequivocally” to have any legal effect. This is counter to a suspect’s notion of the potential importance of being cordial when invoking counsel, as cited in Taylor v. Jackson (2017):

At the beginning of the interview, detectives advised Taylor of his Miranda rights and asked if he would like to talk to them. Taylor said, “I would rather stop. Talk to a lawyer. I mean I’m tryin to be, I’m trying to be cordial, you know what I’m sayin. I’m not about bull shit.” After the detectives attempted to clarify whether Taylor wanted to speak with them, Taylor explained, “I really don’t want to talk because I may want to stop you know, somewhere.” The detectives then explained that Taylor had the right to stop the interview at any time. And Taylor responded, “Well then let’s go then,” and agreed to speak with the detectives.

In Taylor’s police interrogation, Taylor seems to be balancing his desire for counsel with cordialness. He seemed to be attempting to be cooperative, while maintaining his right to secure counsel. The suspect’s background knowledge of how to engage speakers in a face threatening, asymmetric context, however, does not conform to the reality of the interrogation room. Taylor’s reliance on his knowledge of the normative aspects of speech (see Reference FoxFox, 2014), which allow for mutuality of understanding between conversational participants, fails him with regard to invoking the right to counsel. Hence, he waives his right to counsel and proceeds to provide a statement to the police officers.

4.1.3 Mutuality of Understanding in Police Interrogation

Recent research on the use of requests in institutional settings has shed light on the organization of request sequences in these types of encounters. Some of these studies (Reference FoxFox, 2014; Reference Raevaara, Sorjonen, Drew and Couper-KuhlenRaevaara & Sorjonen, 2014) have focused on a type of request traditionally considered pre-requests, such as “do you have X?,” “can I have X?,” or “can you X for me?” This research suggests that in some institutional settings no distinction is made between pre-requests and requests: all requesting utterances are treated as requests (Reference Raevaara, Sorjonen, Drew and Couper-KuhlenRaevaara & Sorjonen, 2014). The view that no distinction holds between the function of pre-requests and requests creates a normative expectation for hearing a person’s utterances as requests, akin to the discussion on types of conventional requests. The research points to the importance of mutuality of understanding, common ground, and preference for progressivity in discourse. As Reference FoxFox (2014) notes “we have thus seen that if preference organization is at work in these sequences, it is a preference for progressivity in moving the sequence forward to granting” (p. 60).

The law’s current, and common, interpretation of indirect invocations as equivocal is at odds with the notion that certain types of requests aim to move the conversation forward. The judiciary’s view of language use, coupled with current police interrogation training, have provided a space in which police officers do not have to share a (discursive) mutuality of understanding or common ground with suspects. This, in turn, interferes with suspects’ ability to invoke their constitutional rights during police questioning. For an invocation for counsel to be granted and move forward the talk, the police interrogation must be “cooperatively constituted as a space for a focused joint activity” (Reference Raevaara, Sorjonen, Drew and Couper-KuhlenRaevaara & Sorjonen, 2014, p. 264). As Excerpt 4.3 further illustrates, in the corpus the invocation stage of a police interrogation is not a space for a focused joint activity, but rather a space where the police interrogator’s agenda is to block the suspect’s attempts at performing a request for counsel.

At about 8.5 minutes into the interrogation, Williams asked whether he could call a lawyer:

1 Defendant: Can I call a lawyer, Mr. Howaniec, son, ‘cause you’re not – you’re not telling me …

2 St. Laurent: So we’re ending this conversation?

3 Defendant: Yeah, you’re not telling me what you’re charging me with. You’re not telling me nothin’.

4 Fillebrown: Well, we’re trying to get there with ya, but …

In Excerpt 4.3, the defendant eventually agrees to speak to the police officers. His inability to obtain counsel and information from the officers, in a sense, “wears him out” until he concedes to waive his rights. The judge presiding the case sided with the police officers and ruled that the invocation was equivocal, the suspect was gauging his options, and the defendant knowingly and voluntarily waived his rights.

It is important to note that there are instances in the corpus that could be considered pre-requests (see Reference LevinsonLevinson, 1983; Reference SchegloffSchegloff, 2007). Speakers may use pre-requests to find out whether they will get a positive response to their request. In a context where speakers have very little information, such as a police interrogation, this type of pre-request would not be unusual. Suspects may employ a pre-request such as “Do you think I should get an attorney?” or “Should I get an attorney?” to ascertain (or as the judges argue potentially “gauge”) whether there are grounds for refusing the request – or getting counsel. The suspect is avoiding making a wrong move that could result in a worse outcome than being interrogated (e.g., being sent to jail for an undetermined period of time, being deemed uncooperative, etc.). These types of requests, hence, require a follow-up move that addresses the suspect’s inquiry. In the corpus, these requests are often dismissed (no information is provided) and/or they are “clarified.”

The notion that a suspect who is “gauging” their options in a police interrogation invalidates the possibility that they may be requesting counsel is a creation of the law and the standards laid forth in Davis and other rulings. In talk, speakers often attempt to achieve multiple functions: politeness, saving face, achieving common ground and mutuality of understanding, etc. These functions may be mediated also by social and cultural factors. As expected, requests and pre requests may be susceptible to misunderstanding and require follow-ups aimed at clarification. These are all potential features of discourse that in practice are handicapped by the law and the limitations it creates when attempting to narrow down the functions of speech in police interrogation.

The next section will examine how police interrogation creates a space of nonmutuality of understanding and noncooperation during the invocation of rights stage of an interrogation. A space that may not conform to the suspects’ understanding of shared knowledge in discourse. For this part of the analysis, the chapter will apply game theory methodology to police–suspect exchanges that include and follow a suspect’s invocation for counsel. This discussion will address how sequences of talk during the invocation of rights stage represent a type of game where one player (custodial suspect) is strategizing in a manner consistent with how speakers attempt to reach mutuality of understanding in conversation, whereas the other player (the interrogator) is simply responding, based on their training, in a manner that appears to address the other players’ turns of talk while invalidating the common knowledge assumption (see Reference Varsos, Flouris, Bitsaki and FasoulakisVarsos et al., 2021). This creates a type of discursive game where one player (custodial suspect) fails to recognize the game as framed and the other player (interrogator) takes advantage of this failure by employing manipulation and deception to change the other player’s discursive preferences.

4.2 Communication As a Type of Game

Linguists have employed game theory to understand how speakers strategically convey meaning and intent in communication. Players have preferences for outcomes that motivate strategic linguistic choices made during the game. Theoretically, in communication as in other games, a player cannot control the outcome of the game just by one’s actions. Instead, a player must take the other player’s linguistic actions into account. This process has traditionally been studied in linguistics under rationalistic game theory (see Reference van Rooijvan Rooij, 2008). Rationalistic game theory examines “when is it rationalizable to communicate at all” and “how can credibility of messages be established” (Reference JägerJäger, 2008, p. 410).

Some common approaches to the credibility question include the application of costly signaling games and cheap talk. Reference RabinRabin (1990), for example, takes a game theoretic approach that is reminiscent of Reference Grice, Cole and MorganGrice’s (1975) cooperative principles that all messages are credible assuming cooperativity. Rabin developed Credible Message Rationalizability (CMR) by combining Reference Crawford and SobelCrawford and Sobel’s (1982) standard equilibrium analysis and Reference Farrell and GibbonsFarrell and Gibbon’s (1989) rich language assumption that players are rational. Players tend to believe statements that are consistent with rationality, allowing for some meaningful communication to be predicted, including those that require implicatureFootnote 3 to derive the players’ intent.

Other approaches predicting communication include Reference BlutnerBlutner’s (2000) Bidirectional Optimality Theory and Reference ParikhParikh’s (1991) Strategic Discourse Model (SDM). Reference Dekker and Van RooyDekker and van Rooij (2000) reformulated Blutner’s theory as the exchange of information between sender and receiver characterized as a strategic signaling game of complete information. The actions of speakers are described as the choice of expressions and the actions of the hearers as the choice of interpretations. These models examine cooperative exchanges, focusing on form-meaning relationships.

Reference ParikhParikh (1991, Reference Parikh2000, Reference Parikh2001) expanded on the analysis of sender and receiver exchanges by adding the sequential features of a communication game of partial information with a unique solution. Reference ParikhParikh (1991) argues that most languages are “situated” which makes language an efficient system of communication: “Once we allow situations a role in the determination of content, it becomes clear that there are certain aspects of utterances that are constant across utterances and others that vary from one situation to another” (p. 475). He notes that part of the task of a theory of communication is to explain how we can get from meaning to content. His model of strategic communication under conditions of ambiguity introduced the concept of “strategic inference” in communication. The central assumption of Parikh’s Strategic Discourse Model (SDM) is that the transfer of information between players involves a strategic interaction between them. When the strategic interaction is common knowledge between the players, that is, when it is a game with a unique solution, the flow will be communicative. Parikh notes “that this game-theoretic structure is situated somewhere, either in the ‘minds’ of players or in their ambient circumstances or both” (p. 478).

Parikh’s SDM, as other models previously discussed, describes how players reach cooperative, meaningful communication, including situations where ambiguity may arise. These approaches, however, do not address noncooperative situations, where players may not have complete information of the signaling strategies of other players (see Reference RabinRabin, 1990; Reference FarrellFarrell, 1993; Reference Asher and LascaridesAsher and Lascarides, 2013). As Reference Pinker, Nowak and LeePinker et al. (2008) note, models of conversation that only assume cooperative agents fail to explain the dynamics of strategic conversations.

Discursive games have also been modeled through game-theoretic constructs such as Bayesian games (Reference Frank and GoodmanFrank and Goodman, 2012; Reference Stevens, Benz, Reuße and KlabundeStevens et al., 2015; Reference BurnettBurnett, 2019; Reference HarsanyiHarsanyi, 1967). In Bayesian games, an agent’s utility is determined not only by actions but also by types of the agents. In these types of games, “the existence of private information leads naturally to attempts by informed parties to communicate (or mislead) and to attempts by uninformed parties to learn and respond” (Reference GibbonsGibbons, 1997, p. 138).

In the analysis of reference, Reference StevensStevens (2016) discusses, through a Bayesian and cognitive lens, whether strategic and nonstrategic thinking play independent roles in explaining pragmatic behavior. Stevens notes that a model that explains interaction must account for why people think strategically and, alternatively, why they may not. Stevens argues that the failure of agents to work out the best strategy for themselves may be rooted in reconciling strategic considerations with situational or cognitive biases. Stevens adds that pragmatic behavior does not always tilt toward strategic optimality and, hence, may only provide partial explanations for complex (linguistic) situations where the choices of strategy may not be obvious.

Rational choice theory may not provide a framework for accounting for an agent’s variances in preferences owing to misperceptions. According to Reference Tversky and KahnemanTversky and Kahneman (1986), the normative analysis in game theory makes four assumptions to develop expected utility theory: cancellation, transitivity, dominance, and invariance. Cancellation eliminates trivial outcomes in which action does not produce different results. Transitivity has a standard mathematical meaning (A≻B, B≻C → A≻C) in which A is preferred (≻) to B, and B is preferred to C, transitivity implies (→) that A is preferred to C. Dominance postulates that if one option is better than another in one state and as good as other options in all other states, it is preferred.

Invariance, which assumes that different representations of the same choice problem should yield the same preference, creates a problem for rational choice theory. Because invariance and dominance are normatively essential, Tversky and Kahneman argue rational choice theory cannot provide a description of choice if an agent shifts their preference unless a fundamental change in perception arises. They find that the normative axioms of rational choice are often violated in situations lacking transparency. To illustrate this point, Tversky and Kahneman show that individuals respond differently to alternative frames of a risky choice, first as the prospect of gaining utility, and second as the prospect of minimizing loss. Even though the alternate statements yield the exact same utility, individuals in their study made different choices depending on how the choice was phrased.

Reference Cason and PlottCason and Plott (2014) assert that the absence of an integrated theory of perception masks the existence of a specific form of misperception: the “failure of game form recognition” (p. 1236). Suffering this type of misperception causes a decision maker to fail “to recognize the proper connections between the acts available for choice and the consequences of choice, which, by necessity, are associated with the method of measuring preferences” (p. 1237). They warn that errors in utility maximization, owing to misperceptions of the game form, lose a separate identity when mistakes are considered generically as an error term, as do errors arising from misinformation, opaque rules, and misperceptions of a situated environment.

Parting from framing theory, the analysis of an unbalanced game model, such as a police interrogation, allows for the examination of differences in each player’s understating of the game and their choices. In these types of games, a player may not be able to recognize the other player’s manipulation of their preference to become that of the other player. Excerpt 4.4 shows a representative excerpt from the corpus that illustrates linguistically how the custodial suspect’s, ![]() ’s, preferences are guided by the interrogator’s,

’s, preferences are guided by the interrogator’s, ![]() ’s, discursive actions.

’s, discursive actions.

1 Officer: Okay. You know what, I have to read them to you anyway regardless of whether you know them or not. You have the right to remain silent, do you understand?

2 Rodriguez: Yes.

3 Officer: Anything you say can be used against you in a court, do you understand?

4 Rodriguez: Yes.

5 Officer: You have the right of the presence of an attorney before and during any questioning, do you understand?

6 Rodriguez: Yes.

7 Officer: If you cannot afford an attorney one will be appointed for you free of charge before any questioning, if you want, do you understand?

8 Rodriguez: Yes.

9 Officer: Okay.

10 The officers then questioned Mr. Rodriguez about his involvement in the drive-by shooting … Eventually, Mr. Rodriguez asked for an attorney:

11 Rodriguez: Can I speak to an attorney?

12 Officer: Whatever you want.

13 Rodriguez: Can I speak to an attorney?

14 Officer: You tell me what you want.

15 Rodriguez: That is what I want.

16 Officer: That’s fine bro we stop because we can’t talk to you anymore, okay, so.

17 Officer: You’re going to be charged with murder today.

18 Rodriguez: Why?

The interrogation continued with the officer vaguely discussing the crime and possible charges. Information is not forthcoming in police interrogations as a matter of training and strategy. The discussion of the attorney resumed to establish that Rodriguez did not want counsel and he waived his rights.

The discursive analysis of Excerpt 4.4 begins with ![]() reading

reading ![]() the Miranda rights. The suspect affirms understanding of the rights and in turn 11 proceeds to invoke the right to counsel: “Can I speak to an attorney?” The invocation is phrased using a hedged indirect request, which may have linguistic moorings in politeness (Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown & Levison, 1987), face (Reference GoffmanGoffman, 1967), risk aversion, as well as in cognitive frameworks and sociolinguistics (see Reference GibbsGibbs, 1983; Reference HoltgravesHoltgraves, 1994; Reference BrooksBrooks, 2000; Reference Holtgraves and AshleyHoltgraves & Ashley, 2001). It may also be natural in the context of asymmetric bargaining and exchanges. Regardless of the explanation, indirectly invoking the right to counsel shows

the Miranda rights. The suspect affirms understanding of the rights and in turn 11 proceeds to invoke the right to counsel: “Can I speak to an attorney?” The invocation is phrased using a hedged indirect request, which may have linguistic moorings in politeness (Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown & Levison, 1987), face (Reference GoffmanGoffman, 1967), risk aversion, as well as in cognitive frameworks and sociolinguistics (see Reference GibbsGibbs, 1983; Reference HoltgravesHoltgraves, 1994; Reference BrooksBrooks, 2000; Reference Holtgraves and AshleyHoltgraves & Ashley, 2001). It may also be natural in the context of asymmetric bargaining and exchanges. Regardless of the explanation, indirectly invoking the right to counsel shows ![]() ’s preference to invoke counsel and do so in a manner that fits

’s preference to invoke counsel and do so in a manner that fits ![]() ’s understanding of formulating requests in conversation, particularly asymmetric ones (Reference MasonMason, 2013).Footnote 4

’s understanding of formulating requests in conversation, particularly asymmetric ones (Reference MasonMason, 2013).Footnote 4

The use of an indirect request, in light of the Davis ruling, places ![]() ’s ability to invoke counsel in the hands of

’s ability to invoke counsel in the hands of ![]() . As noted previously,

. As noted previously, ![]() is not required by law to inform

is not required by law to inform ![]() that the invocation does not rise to the level of unequivocalness to end an interrogation.

that the invocation does not rise to the level of unequivocalness to end an interrogation. ![]() , however, cannot coerce

, however, cannot coerce ![]() into not invoking rights. Statements must be provided voluntarily or have the appearance as such. This creates a situation in which

into not invoking rights. Statements must be provided voluntarily or have the appearance as such. This creates a situation in which ![]() does not provide information to

does not provide information to ![]() , but has to appear to address

, but has to appear to address ![]() ’s indirect request.

’s indirect request.

The next turns of talk (turns 12–15) constitute ![]() ’s repeated attempts at invoking counsel and restating his preference, which is met with

’s repeated attempts at invoking counsel and restating his preference, which is met with ![]() ’s lack of acknowledgment of such attempts. Of note, follow-up moves are commonly used in conversation to clarify, repair, and/or respond to a prior turn of talk.

’s lack of acknowledgment of such attempts. Of note, follow-up moves are commonly used in conversation to clarify, repair, and/or respond to a prior turn of talk. ![]() ’s “whatever you want” or “you tell me what you want” does not address directly

’s “whatever you want” or “you tell me what you want” does not address directly ![]() ’s request for counsel or further

’s request for counsel or further ![]() ’s ability to invoke counsel.

’s ability to invoke counsel. ![]() , hence, continues to assert his preference for counsel and repeatedly invokes counsel in turns 11, 13, and 15, albeit successfully only in turn 15.

, hence, continues to assert his preference for counsel and repeatedly invokes counsel in turns 11, 13, and 15, albeit successfully only in turn 15.

In turn 16, ![]() changes his follow-up response to: “That’s fine bro we stop because we can’t talk to you anymore, okay, so,” which is the first follow-up to address the outcome of

changes his follow-up response to: “That’s fine bro we stop because we can’t talk to you anymore, okay, so,” which is the first follow-up to address the outcome of ![]() invoking counsel (“we can’t talk to you anymore”), but without overtly acknowledging

invoking counsel (“we can’t talk to you anymore”), but without overtly acknowledging ![]() ’s invocation. In turn 17,

’s invocation. In turn 17, ![]() interjects with: “You’re going to be charged with murder today.” This statement leads

interjects with: “You’re going to be charged with murder today.” This statement leads ![]() to inquire “why?,” which brings

to inquire “why?,” which brings ![]() back to the interrogation table and away from his initial, and sustained, preference to request counsel. The talk continues and eventually

back to the interrogation table and away from his initial, and sustained, preference to request counsel. The talk continues and eventually ![]() waives his rights and provides incriminating statements. This is

waives his rights and provides incriminating statements. This is ![]() ’s preferred outcome based on his training: to get a statement from

’s preferred outcome based on his training: to get a statement from ![]() .

.

In Excerpt 4.4, ![]() ’s continued attempts to invoke counsel indirectly, coupled with

’s continued attempts to invoke counsel indirectly, coupled with ![]() ’s strategic use of follow-up moves, serve to misdirect

’s strategic use of follow-up moves, serve to misdirect ![]() from invoking counsel. The ultimate success of the strategy shows

from invoking counsel. The ultimate success of the strategy shows ![]() exhibiting what Reference Gharesifard and CortésGharesifard and Cortés (2010, p. 1077) note is an “imprecise understanding about the objectives and true intentions of other players.”

exhibiting what Reference Gharesifard and CortésGharesifard and Cortés (2010, p. 1077) note is an “imprecise understanding about the objectives and true intentions of other players.” ![]() attempts to invoke counsel repeatedly, yet

attempts to invoke counsel repeatedly, yet ![]() does not question the follow-ups by

does not question the follow-ups by ![]() that do not address his attempts at invoking counsel, nor does

that do not address his attempts at invoking counsel, nor does ![]() change strategy to use another type of request for counsel (e.g., invoke directly). These options, otherwise available in talk, are not pursued by

change strategy to use another type of request for counsel (e.g., invoke directly). These options, otherwise available in talk, are not pursued by ![]() because

because ![]() does not recognize that

does not recognize that ![]() ’s utterances were deemed equivocal and

’s utterances were deemed equivocal and ![]() does not have to accept (by law) these utterances as invocations for counsel, regardless of the reading of the Miranda rights.

does not have to accept (by law) these utterances as invocations for counsel, regardless of the reading of the Miranda rights. ![]() continues to participate as if the conversation abides by commonality of understanding where indirectly formulated requests are understood as unambiguous requests.

continues to participate as if the conversation abides by commonality of understanding where indirectly formulated requests are understood as unambiguous requests.

On ![]() ’s third attempt at invoking counsel,

’s third attempt at invoking counsel, ![]() indirectly acknowledges

indirectly acknowledges ![]() ’s invocation by stating the consequences of the decision. However,

’s invocation by stating the consequences of the decision. However, ![]() follows up by telling

follows up by telling ![]() “You’re going to be charged with murder today.” This “distracts”

“You’re going to be charged with murder today.” This “distracts” ![]() into engaging with

into engaging with ![]() as a cooperative conversational participant.

as a cooperative conversational participant. ![]() is lured back into conversation because

is lured back into conversation because ![]() believes

believes ![]() will share information about why

will share information about why ![]() will be charged in the case. The information is not forthcoming, but it did return

will be charged in the case. The information is not forthcoming, but it did return ![]() to the invocation stage of the interrogation, and, in this case,

to the invocation stage of the interrogation, and, in this case, ![]() waived the right to legal counsel and agreed to talk with the interrogator.

waived the right to legal counsel and agreed to talk with the interrogator.

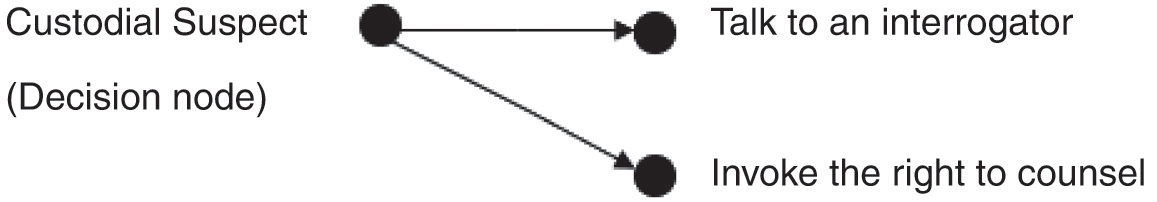

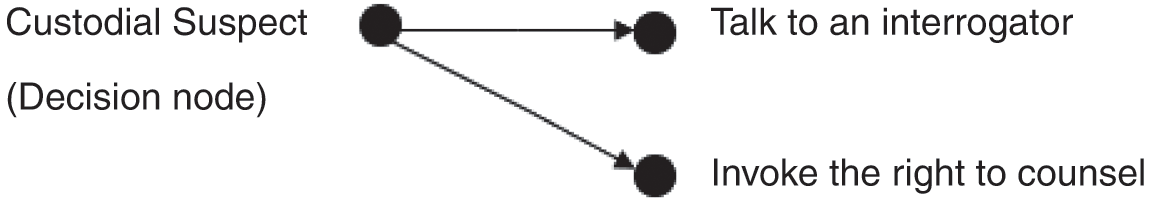

Incorporating perceptions into the analysis of discursive strategies prompts the question of whether Bayesian analysis, commonly used in linguistics, or an alternate model should be considered to describe the actions observed in Excerpt 4.4. Bayesian analysis is based on rational utility maximization measured as the sum of the subjectively assessed utility of each outcome weighted by the probability of its occurrence. The surface game, depicted in Figure 4.1 (Reference Mason and MasonMason & Mason, 2021), is a simplified Bayesian model in which ![]() has 100 percent certainty of obtaining either outcome: choosing to talk to an interrogator or invoking the right to counsel.

has 100 percent certainty of obtaining either outcome: choosing to talk to an interrogator or invoking the right to counsel.

Figure 4.1 The surface game

If ![]() chooses to invoke the right to legal counsel, shown as the arrow pointing to the lower circle on the right, whenever counsel arrives the invocation game becomes the interrogation game, and all future decisions will be generated from this lower node.

chooses to invoke the right to legal counsel, shown as the arrow pointing to the lower circle on the right, whenever counsel arrives the invocation game becomes the interrogation game, and all future decisions will be generated from this lower node. ![]() has a preference that

has a preference that ![]() chooses the other path, and

chooses the other path, and ![]() has strategies to shift

has strategies to shift ![]() preference.

preference.

The surface game is the game as presented to the ![]() . However, as observed in the corpus (see Excerpt 4.4), something more than the surface game takes place.

. However, as observed in the corpus (see Excerpt 4.4), something more than the surface game takes place. ![]() has institutional powers that grant

has institutional powers that grant ![]() a choice of outcome, the linguistic and procedural response in conversation with

a choice of outcome, the linguistic and procedural response in conversation with ![]() , to shape

, to shape ![]() ’s perceptions. These powers include

’s perceptions. These powers include ![]() ’s ability to limit

’s ability to limit ![]() ’s discursive options to express preference; to control new information to influence

’s discursive options to express preference; to control new information to influence ![]() ; and to impose the least preferred outcome on

; and to impose the least preferred outcome on ![]() . This is accomplished through

. This is accomplished through ![]() ’s initiated follow-up moves. The observed shifts in

’s initiated follow-up moves. The observed shifts in ![]() ’s responses, from invoking counsel to talking to an interrogator without counsel, may not be the product of individual free will, as cited in numerous legal cases, but the product of

’s responses, from invoking counsel to talking to an interrogator without counsel, may not be the product of individual free will, as cited in numerous legal cases, but the product of ![]() ’s “failure of game form recognition” that accommodates misperceptions arising from other psychological, discursive, and deceptive influences.

’s “failure of game form recognition” that accommodates misperceptions arising from other psychological, discursive, and deceptive influences.

The nuances that institutional power brings to game theory, as summarized by Reference PratesPrates (2014), incorporates into game theory the use of power by one agent to alter the options of another agent:

It should be emphasized that the only form of power is the exercise of power, not its mere possession. This means that an agent with power will always exercise it, as generates better results for him. It is also important to highlight that game theory usually encompasses different games when the action-environment changes. For instance, when power is incorporated into a specific game, the use of power by an agent generates a new game, which transforms the options set of the player subjected by the power relation.

Prates points out what is essentially applicable to any successful hypergame employed by ![]() and embedded within an invocation game: preferences shift. The shift in preferences can be thought of as new conditions that must be met for

and embedded within an invocation game: preferences shift. The shift in preferences can be thought of as new conditions that must be met for ![]() to invoke a particular action because the environment changes and not the assessed risk.

to invoke a particular action because the environment changes and not the assessed risk.

In Figure 4.1, the switch from the lower node to the higher node (i.e., from invoking the right to counsel to waiving that right) entails a different risk environment for ![]() . As Prates notes: new game, new player, new standards. In an extensive form rendition of the game, subsequent action switches from one pathway to another. The shift creates a new game outside of Bayesian sequential analysis. The hypergame creates the shift observed in Excerpt 4.4.

. As Prates notes: new game, new player, new standards. In an extensive form rendition of the game, subsequent action switches from one pathway to another. The shift creates a new game outside of Bayesian sequential analysis. The hypergame creates the shift observed in Excerpt 4.4.

This chapter proposes an alternative to rational choice theory to investigate why discursive preferences shift in real world applications, such as police interrogations (see also Reference Mason and MasonMason & Mason, 2023). The analysis this approach produces will provide insights into the effect of institutional power in framing “the invocation game” as a type of hypergame:

Figuring out what strategy a player will use is dependent upon not only his or her observation of the game, but also how that player believes their opponent is viewing the game … The goal of hypergame analysis is to provide insight into real-world situations that are often more complex than a game where the choices of strategy present themselves as obvious.

4.3 Hypergame Dynamics

Hypergame Theory (HgT) expands traditional game theory and noncooperative game theory (see Reference Fudenberg and TiroleFudenberg & Tirole, 1991) by incorporating players’ perceptions of other players’ preferences into their strategic action (see Reference BennettBennett, 1977; Reference Wang, Hipel and FraserWang et al., 1989; Reference Basar and OlsderBaşar & Olsder, 1999). HgT accommodates a player with the power to shape the game while it is being played to exercise that power strategically guided by that player’s perceptions of other player’s preferences. In the invocation game, ![]() controls the discursive exchanges, which confers to

controls the discursive exchanges, which confers to ![]() an advantage over

an advantage over ![]() . During the game,

. During the game, ![]() accumulates information on

accumulates information on ![]() ’s preferences.

’s preferences. ![]() uses that information strategically in choosing outcomes to influence

uses that information strategically in choosing outcomes to influence ![]() ’s perception of the invocation game and to shape the game, while it is being played, to shift

’s perception of the invocation game and to shape the game, while it is being played, to shift ![]() ’s preferences to conform with

’s preferences to conform with ![]() ’s. Within the invocation game, each turn of talk produces an ordered pair of ranked preferences for

’s. Within the invocation game, each turn of talk produces an ordered pair of ranked preferences for ![]() and

and ![]()

![]() over

over ![]() ’s choices: (a) waive rights and agree to interrogation, (b) stay silent, (c) engage in talk, and (d) invoke the right to legal counsel.

’s choices: (a) waive rights and agree to interrogation, (b) stay silent, (c) engage in talk, and (d) invoke the right to legal counsel. ![]() ’s preferences are given initially by nature, are fluid to the situation, and are updated after each turn of

’s preferences are given initially by nature, are fluid to the situation, and are updated after each turn of ![]() ’s talk.

’s talk.

For ![]() , it is easiest to obtain a statement if no legal counsel is present with the

, it is easiest to obtain a statement if no legal counsel is present with the ![]() . An interrogation with a lawyer present is preferable to silence. Talk is preferred to an interrogation with a lawyer present because talk is an opportunity for

. An interrogation with a lawyer present is preferable to silence. Talk is preferred to an interrogation with a lawyer present because talk is an opportunity for ![]() to persuade

to persuade ![]() to consent to speak without an attorney. It should also be noted that anything

to consent to speak without an attorney. It should also be noted that anything ![]() says can be used against

says can be used against ![]() in a court of law, making all conversation, by default, in the realm of an interrogation without legal counsel, the most preferred outcome of all.

in a court of law, making all conversation, by default, in the realm of an interrogation without legal counsel, the most preferred outcome of all.

The legal framework in which police interrogation operates creates two hypergames in which at least one player’s strategy is determined by their perception of the other player’s preferences. The next sections provide the notation and modeling of the hypergames and the application of hypergame modeling to representative excerpts from the corpus.

4.3.1 Hypergame Notation of the Invocation Game

The invocation game adopts Reference Gharesifard and CortesGharesifard and Cortés’s (2014) notation where a game ![]() , consists of a vector of two players

, consists of a vector of two players ![]() , an outcome vector

, an outcome vector ![]() with cardinality

with cardinality ![]() , where

, where ![]() is one of two outcomes arising from

is one of two outcomes arising from ![]() taking action

taking action ![]() :

:

| Variable | Description of action |

|---|---|

| Agree to an interrogation, | |

| Remain silent, | |

| Engage in talk, | |

| Invoke right to counsel |

![]() will make a choice to invoke or waive, and both

will make a choice to invoke or waive, and both ![]() and

and ![]() will derive utility from

will derive utility from ![]() ’s choice generating a preference rank

’s choice generating a preference rank ![]() of outcomes for

of outcomes for ![]() and

and ![]() :

: ![]() . Preference is measured along a sequence of events.

. Preference is measured along a sequence of events.

The surface game is a single move game. The game begins formulaically with the reading of Miranda rights. The choice by ![]() either to invoke

either to invoke ![]() or to waive

or to waive ![]() generates the outcome preference rank

generates the outcome preference rank ![]() . Within the game, two other moves

. Within the game, two other moves ![]() (silence) and

(silence) and ![]() (talk) are allowed, but these additional moves occur around

(talk) are allowed, but these additional moves occur around ![]() ’s choice:

’s choice: ![]() or

or ![]() . Since both

. Since both ![]() and

and ![]() entail conversation

entail conversation ![]() , they are subsets of talk:

, they are subsets of talk: ![]() . Given the specific inclusion of

. Given the specific inclusion of ![]() and

and ![]() as choices in the game, we distinguish

as choices in the game, we distinguish ![]() to be talk that excludes invoking and waiving the right to counsel:

to be talk that excludes invoking and waiving the right to counsel: ![]() .

.

I’s preference among outcomes, ![]() , is assumed constant by training and will guide

, is assumed constant by training and will guide ![]() ’s strategy when engaging with

’s strategy when engaging with ![]() .

. ![]() most prefers an interrogation without a lawyer present because the absence of a lawyer makes obtaining a statement from

most prefers an interrogation without a lawyer present because the absence of a lawyer makes obtaining a statement from ![]() easier.

easier. ![]() prefers conversation

prefers conversation ![]() to a decision by

to a decision by ![]() to invoke the right to a lawyer

to invoke the right to a lawyer ![]() because it leaves open the possibility of persuading

because it leaves open the possibility of persuading ![]() to talk without a lawyer, and

to talk without a lawyer, and ![]() least prefers silence as silence does not further

least prefers silence as silence does not further ![]() ’s investigation.

’s investigation.

The invocation game situates discourse for ![]() .

. ![]() has exactly two powers: the right to remain silent and the right to have a lawyer present for questioning. The power dynamics are evident from what transpires in an interrogation:

has exactly two powers: the right to remain silent and the right to have a lawyer present for questioning. The power dynamics are evident from what transpires in an interrogation: ![]() has lost the right to freedom and faces the possibility of imprisonment.

has lost the right to freedom and faces the possibility of imprisonment. ![]() ’s preference rank,

’s preference rank, ![]() , is fluid to the situation and is updated after each turn of

, is fluid to the situation and is updated after each turn of ![]() ’s talk

’s talk ![]() . Any

. Any ![]() who prefers

who prefers ![]() will end the game by not engaging in the interrogation, albeit while being detained in jail, or, in some instances, with the release of

will end the game by not engaging in the interrogation, albeit while being detained in jail, or, in some instances, with the release of ![]() (e.g., at the discretion of

(e.g., at the discretion of ![]() ).

).

For those ![]() willing to talk,

willing to talk, ![]() ’s preference rankings are given as a state of nature

’s preference rankings are given as a state of nature ![]() . Therefore,

. Therefore, ![]() ’s preferences manifest from nature as either

’s preferences manifest from nature as either ![]() or as

or as ![]() . Both

. Both ![]() and

and ![]() are presumed to be preferred to

are presumed to be preferred to ![]() owing to a preference for relevant conversation over irrelevant conversation, because engaging in talk may lead to providing incriminating statements. Therefore,

owing to a preference for relevant conversation over irrelevant conversation, because engaging in talk may lead to providing incriminating statements. Therefore, ![]() is held in reserve until

is held in reserve until ![]() is perceived to hold strategic value (e.g., request information or clarification) at which point

is perceived to hold strategic value (e.g., request information or clarification) at which point ![]() reveals

reveals ![]() or

or ![]() . Once

. Once ![]() loses strategic value, preferences revert to their previous state unless the discourse altered

loses strategic value, preferences revert to their previous state unless the discourse altered ![]() ’s preference ranking.

’s preference ranking.

4.4 Two Hypergames

4.4.1 Type 1 Hypergame: CS Initiates

Type 1 hypergame originates after ![]() initiates conversation

initiates conversation ![]() . The strategic value of

. The strategic value of ![]() for

for ![]() ranges from human need (e.g., a desire for water) to probing for information. The success or failure of

ranges from human need (e.g., a desire for water) to probing for information. The success or failure of ![]() ’s initiative depends on the willingness of

’s initiative depends on the willingness of ![]() to grant such success. Leaving aside human rights violations (e.g., denying requested water),

to grant such success. Leaving aside human rights violations (e.g., denying requested water), ![]() has the ability to shift the topic of

has the ability to shift the topic of ![]() . This topic shift is the type 1 hypergame depicted in Figure 4.2 (Reference Mason and MasonMason & Mason, 2021). In this subgame, the shifted conversation continues with the participants denoted as

. This topic shift is the type 1 hypergame depicted in Figure 4.2 (Reference Mason and MasonMason & Mason, 2021). In this subgame, the shifted conversation continues with the participants denoted as ![]() and

and ![]() until either

until either ![]() reposes the Miranda question, or

reposes the Miranda question, or ![]() declares

declares ![]() or attempts to invoke

or attempts to invoke ![]() which returns the conversation to the

which returns the conversation to the ![]() decision node.

decision node.

Figure 4.2 Type I Hypergame: ![]() initiates

initiates ![]()

4.4.2 Type 2 Hypergame: I Initiates

In the type 2 hypergame, ![]() makes an indirectly formulated assertion of

makes an indirectly formulated assertion of ![]() , and

, and ![]() initiates conversation

initiates conversation ![]() to divert

to divert ![]() away from

away from ![]() . The conversation continues until

. The conversation continues until ![]() asserts

asserts ![]() or

or ![]() , or until

, or until ![]() becomes convinced

becomes convinced ![]() ’s position has changed at which point

’s position has changed at which point ![]() reposes the Miranda question. The type 2 hypergame is depicted in Figure 4.3 (Reference Mason and MasonMason & Mason, 2021).

reposes the Miranda question. The type 2 hypergame is depicted in Figure 4.3 (Reference Mason and MasonMason & Mason, 2021).

Figure 4.3 Type 2 Hypergame: ![]() initiates

initiates ![]() to divert

to divert ![]() away from

away from ![]()

4.5 Analyzing the Invocation Game and Its Hypergames

The two hypergames illustrated in Figures 4.2 and 4.3 show the assertion of power in which ![]() takes footingFootnote 5 from

takes footingFootnote 5 from ![]() to influence the outcome of the game by controlling the topic of conversation. In a noncooperative asymmetric exchange, the person who controls the talk may direct the exchanges without regard for mutuality of understanding. In the invocation game,

to influence the outcome of the game by controlling the topic of conversation. In a noncooperative asymmetric exchange, the person who controls the talk may direct the exchanges without regard for mutuality of understanding. In the invocation game, ![]() , guided by perceptions of what motivates

, guided by perceptions of what motivates ![]() , works to influence

, works to influence ![]() to

to ![]() ’s desired preference.

’s desired preference. ![]() will be handicapped from achieving discursive goals if

will be handicapped from achieving discursive goals if ![]() does not recognize how the talk is situated.

does not recognize how the talk is situated. ![]() protects

protects ![]() ’s misunderstanding instead of eliminating it. An equivocal/ambiguous invocation for counsel allows

’s misunderstanding instead of eliminating it. An equivocal/ambiguous invocation for counsel allows ![]() to ask follow-up questions aimed at “clarifying” the invocation.

to ask follow-up questions aimed at “clarifying” the invocation. ![]() is not required to take any action, such as initiating the process

is not required to take any action, such as initiating the process ![]() , making the follow-up an empty rhetorical clarification. The analysis of Excerpt 4.5, previously cited as Excerpt 4.2, will show how

, making the follow-up an empty rhetorical clarification. The analysis of Excerpt 4.5, previously cited as Excerpt 4.2, will show how ![]() manipulates

manipulates ![]() ’s preferences through a series of commonly observed extensive moves, with multiple iterations, to match

’s preferences through a series of commonly observed extensive moves, with multiple iterations, to match ![]() ’s own.

’s own.

1 Mande: And if you decide to answer questions now, without a lawyer present, you have the right to stop answering questions at any time.

2 Davis: If, if I’m, if I’m going to answer questions, I’m going to need a lawyer here.

3 Mande: Alright, well, this is just so you understand that … and then down here, it’s just now we’re, this is the part where, if you want a way to talk to us and answer questions, that’s where you sign there. If you don’t want to talk to us, don’t …

4 Davis: I want to talk to you, but I just need my lawyer.

5 Chaney: Ok, ok, so here’s what you’re telling us – you do want your lawyer?

6 Davis: I want to talk, yeah. But I need my lawyer present.

7 Chaney: We wanna … either you talk to us now … if you want to talk to us now, without anybody else present, you have to sign that waiver. If not, all bets are off, you go into the system, ok?

8 Davis: Yeah.

The surface game commences at the end of turn 1. After listening to the Miranda rights, ![]() asserts

asserts ![]() in turn 2 revealing

in turn 2 revealing ![]() . In turn 3,

. In turn 3, ![]() initiates a type 2 hypergame with

initiates a type 2 hypergame with ![]() in which

in which ![]() provides unsolicited information. Viewed as a cooperative move,

provides unsolicited information. Viewed as a cooperative move, ![]() ’s “clarification” implies that

’s “clarification” implies that ![]() can choose

can choose ![]() and assert

and assert ![]() “at any time” implying

“at any time” implying ![]() is a subset of

is a subset of ![]() . This “clarification” reduces the perceived cost of

. This “clarification” reduces the perceived cost of ![]() because, by implication,

because, by implication, ![]() is already a part of

is already a part of ![]() .

.

![]() responds to

responds to ![]() ’s type 2 hypergame in turn 4 as in turn 2 except

’s type 2 hypergame in turn 4 as in turn 2 except ![]() couches this assertion of

couches this assertion of ![]() by first presenting a cooperative ethos. The effect is a short apology made prior to exercising self-interest. This statement should end the game for a second time, but in turn 5

by first presenting a cooperative ethos. The effect is a short apology made prior to exercising self-interest. This statement should end the game for a second time, but in turn 5 ![]() engages the type 2 hypergame a second time by presenting

engages the type 2 hypergame a second time by presenting ![]() that appears at first as a summary but changes into what appears to be a clarifying question. Almost word for word,

that appears at first as a summary but changes into what appears to be a clarifying question. Almost word for word, ![]() repeats the preference expressed in turn 4 and now again in turn 6, and once more the invocation game should end.

repeats the preference expressed in turn 4 and now again in turn 6, and once more the invocation game should end.

In the third iteration of the type 2 hypergame, ![]() shifts strategy to employ an ominous tone. After an initial misstep in turn 7,

shifts strategy to employ an ominous tone. After an initial misstep in turn 7, ![]() returns the conversation directly to

returns the conversation directly to ![]() ’s decision node by presenting alternative

’s decision node by presenting alternative ![]() with its procedure of signing a waiver, or, if

with its procedure of signing a waiver, or, if ![]() does not choose

does not choose ![]() , an outcome with no certainty and an unknown procedure which will be no better than

, an outcome with no certainty and an unknown procedure which will be no better than ![]() .

. ![]() concludes turn 7 by asking “ok?” Here “ok” is a request for

concludes turn 7 by asking “ok?” Here “ok” is a request for ![]() to confirm that

to confirm that ![]() understands

understands ![]() ’s choices which do not explicitly include

’s choices which do not explicitly include ![]() .

.

![]() has reshaped

has reshaped ![]() ’s perception of the game. In turn 6,

’s perception of the game. In turn 6, ![]() asserts

asserts ![]() with conviction, just as in turn 4. In turn 8,

with conviction, just as in turn 4. In turn 8, ![]() reveals that the perceived value of the alternative to

reveals that the perceived value of the alternative to ![]() has become worse than it was in turn 6 because the alternative to

has become worse than it was in turn 6 because the alternative to ![]() in turn 6 was

in turn 6 was ![]() but in turn 8 the alternative to

but in turn 8 the alternative to ![]() is one of uncertainty, as alluded to with the reference to betting, except instead of a payout of

is one of uncertainty, as alluded to with the reference to betting, except instead of a payout of ![]() there is certainty of going into the “system.” After turn 8,

there is certainty of going into the “system.” After turn 8, ![]() signs a waiver revealing the shift to

signs a waiver revealing the shift to ![]() brought on by

brought on by ![]() ’s statement in turn 7.

’s statement in turn 7.

Excerpt 4.6 provides another example of the hypergames played in a police interrogation.

1 Detective Holliday: So you understand each of your rights?

2 Brandon Johnson: Yes.

3 Detective Holliday: Are you willing to give up these rights and answer questions or make statements at this time?

4 Brandon Johnson: Ah, I really would like to have a lawyer present.

5 Detective Holliday: Okay.

6 Brandon Johnson: Because I know how serious this is.

7 Detective Holliday: Hm-hm.

8 Brandon Johnson: And I don’t have anything to hide. I will talk to you guys. You know, I’ll tell you any and everything I know, you know. But, um, I just wondered what like what kind of questions would you like to ask me or anything?

9 Detective Holliday: Well you, for, for you to find that out though.

10 Brandon Johnson: I gotta answer these questions though on paper.

11 Detective Holliday: Pardon?

12 Brandon Johnson: You said I gotta, I gotta answer these questions on the paper.

13 Detective Holliday: No. Well no, no. You answered them [Miranda warnings]. But you just said you wanted a lawyer which means I can’t ask, tell you what the questions are gonna be without a lawyer being present. Now do you wanna waive your right to a lawyer? You understand that at any time, you can change your mind and stop talking and stop answering questions. You can ask for that lawyer at that time, whatever. But because you’re thinking about asking for a lawyer—.

14 Brandon Johnson: Well I understand that.

15 Detective Holliday: Alright. That, I, I don’t, you’re in control here guy.

16 Brandon Johnson: Right, alright, alright. I understand that. You can, um.

17 Detective Holliday: You’re in control.

18 Brandon Johnson: _______, you can, you can.

19 Detective Holliday: You wanna waive your rights and talk to us right now?

20 Brandon Johnson: I can talk to you, yes.

21 Detective Holliday: Okay. So the answers yes?

22 Brandon Johnson: Yes.

Excerpt 4.6 is situated at the initial stage of the invocation game initiated by ![]() ’s reading of the Miranda rights. In turn 1,

’s reading of the Miranda rights. In turn 1, ![]() seeks affirmation from

seeks affirmation from ![]() that

that ![]() understands these rights and warnings.

understands these rights and warnings. ![]() affirms in turn 2.

affirms in turn 2. ![]() then imposes a decision on

then imposes a decision on ![]() in turn 3:

in turn 3: ![]() or not

or not ![]() ?

? ![]() responds by indirectly invoking the right to counsel in turn 4 which reveals

responds by indirectly invoking the right to counsel in turn 4 which reveals ![]() .

. ![]() appears to acknowledge the invocation in turn 5.

appears to acknowledge the invocation in turn 5.

In turn 6, ![]() initiates a type 1 hypergame with

initiates a type 1 hypergame with ![]() which reveals a shift in preference

which reveals a shift in preference ![]() . Strategically, it seems that

. Strategically, it seems that ![]() is apologizing for, or justifying,

is apologizing for, or justifying, ![]() ’s assertion of

’s assertion of ![]() , perhaps responding to the perceived power dynamics between

, perhaps responding to the perceived power dynamics between ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() acknowledges the expression, then in turn 8

acknowledges the expression, then in turn 8 ![]() executes a strategic probe for information.

executes a strategic probe for information. ![]() defers providing information, and then

defers providing information, and then ![]() asks a procedural question in turn 10,

asks a procedural question in turn 10, ![]() expresses a need for clarification,

expresses a need for clarification, ![]() repeats the question in turn 12, and then

repeats the question in turn 12, and then ![]() makes the strategic move in turn 13 to shift the topic back to the question of waiving or invoking the right to counsel, as if

makes the strategic move in turn 13 to shift the topic back to the question of waiving or invoking the right to counsel, as if ![]() had not expressed an opinion.

had not expressed an opinion.

Turn 14 shows that in ![]()

![]() has gone from seeker to provider of information by acknowledging the procedure for the dispreferred choice

has gone from seeker to provider of information by acknowledging the procedure for the dispreferred choice ![]() and that

and that ![]() does not negate

does not negate ![]() . In turn 15,

. In turn 15, ![]() does not acknowledge the lingering invocation and instead asserts that

does not acknowledge the lingering invocation and instead asserts that ![]() is in control and must yet decide what to do. In taking this action,

is in control and must yet decide what to do. In taking this action, ![]() asserts a perception of how power is situated in the talk that is contrary to reality. Had

asserts a perception of how power is situated in the talk that is contrary to reality. Had ![]() been able to assert footing, the invocation of turn 4 would have been acknowledged. Instead, it stands as a powerless utterance.

been able to assert footing, the invocation of turn 4 would have been acknowledged. Instead, it stands as a powerless utterance.

![]() agrees four times in turn 16 to the illusion

agrees four times in turn 16 to the illusion ![]() gives in turn 15, but then

gives in turn 15, but then ![]() expresses confusion.

expresses confusion. ![]() provides a (mis)guiding reaffirmation that

provides a (mis)guiding reaffirmation that ![]() is in control.

is in control. ![]() assumes control by twice starting an assertion of what

assumes control by twice starting an assertion of what ![]() can do in turn 18 to which

can do in turn 18 to which ![]() helpfully completes the thought asking if

helpfully completes the thought asking if ![]() wants

wants ![]() . Turn 20 reveals the important change:

. Turn 20 reveals the important change: ![]() , and with a request for clarification in turn 20,

, and with a request for clarification in turn 20, ![]() confirms in turn 21.

confirms in turn 21.

But, why did ![]() ’s preferences change? Key to understanding the change is the fact that during the conversation no new information about circumstances or procedure were provided, despite

’s preferences change? Key to understanding the change is the fact that during the conversation no new information about circumstances or procedure were provided, despite ![]() ’s probe for this information. The only notable topic that arises is one of power: who is in control of the situation. Within the conversation,

’s probe for this information. The only notable topic that arises is one of power: who is in control of the situation. Within the conversation, ![]() ’s tone changes from one of certainty about preference, to a small hesitation in the probe for information in turn 8, to a desire for affirmation of understanding of the procedure in turns 10 and 12, and then to the shift in footing from being a requester of information to a provider.

’s tone changes from one of certainty about preference, to a small hesitation in the probe for information in turn 8, to a desire for affirmation of understanding of the procedure in turns 10 and 12, and then to the shift in footing from being a requester of information to a provider.

Perhaps the incongruous nature of an exchange in which the one who gives up information is portrayed as being in control is as confusing as it is comforting. After the reassuring illusion of control, ![]() switches to trust the situation and relinquish all control by waiving the right to legal counsel. It may seem that

switches to trust the situation and relinquish all control by waiving the right to legal counsel. It may seem that ![]() has switched from skepticism of

has switched from skepticism of ![]() to trusting

to trusting ![]() , but in probing for information in turn 8 it shows that

, but in probing for information in turn 8 it shows that ![]() believes

believes ![]() is willing to be helpful, an illusion furthered by the illusion of control.

is willing to be helpful, an illusion furthered by the illusion of control. ![]() has reassured

has reassured ![]() to see the talk as situated cooperatively with

to see the talk as situated cooperatively with ![]() in the position of power.

in the position of power. ![]() implies that

implies that ![]() because if

because if ![]() is chosen both

is chosen both ![]() and

and ![]() remain as options, and

remain as options, and ![]() is the way to satisfy the curiosity

is the way to satisfy the curiosity ![]() expressed in turn 8.

expressed in turn 8. ![]() affirms the change in preference by requesting clarification consistent with a cooperatively situated exchange in turn 21, and