The dogs chase the last jackal.

When Boipelo’s pregnancy began showing, at about four months, her mother Khumo hastened halfway across the village to her own mother’s – Mmapula’s – home. Boipelo, not yet 20, was the eldest of Khumo’s six children. Khumo was a calm and pragmatic woman, extremely hard-working, independent, and reserved, sometimes recalcitrant. But on that day, her report to her mother was frustrated and despairing: ‘Who could the boy be, in this village? They’re useless! Unemployed, no money. How will we look after a baby?’ Khumo and her children lived in a cramped, two-room lean-to, and they struggled to make ends meet. Boipelo had just finished school, and her mother had hoped she would find work and help build a house. Instead, there was a baby on the way.

Lorato, Boipelo’s older cousin, fell pregnant at roughly the same time. Lorato knew about Boipelo’s pregnancy from the beginning, but she told no one at home about her own. Knowing that it would put enormous pressure on the family to have two babies at once, Lorato and her boyfriend considered crossing the border for an abortion in South Africa. But he had a good job and was building a house in the city – perhaps, she thought, they could manage to raise a baby on their own. They decided to keep the child.

Lorato’s pregnancy started showing shortly after Boipelo’s. When Mmapula noticed, she sent two of her daughters to call Lorato and confront her. Having had her suspicions confirmed, the old woman hastened down the street to confer with trusted neighbours (who were also relations). She was as frustrated and despairing as Khumo had been a few short weeks before.

The double pregnancy happened before I returned to Botswana for fieldwork, but I received a formal and somewhat disconsolate email from Kelebogile informing me of the situation – a rare occurrence in its own right. Lorato had recounted the events to me within days of my arriving back, and, over time, Oratile and Kelebogile filled in bits and pieces as well. For many of my friends in Botswana, as well as for Boipelo and Lorato, pregnancy marked a major watershed in relationships with lovers, in family relationships, and in life trajectories. In most cases, it preceded – but seldom precipitated – marriage (a long-standing trend; see Comaroff and Roberts Reference Comaroff and Roberts1977: 99; Gulbrandsen Reference Gulbrandsen1986; Lye and Murray Reference Lye and Murray1980; Schapera Reference Schapera1933; Townsend Reference Townsend1997). Pregnancy was often, though not always, the point at which a courtship became unavoidably apparent. It brought sexual relationships, otherwise carefully kept secret, into the sphere of the seen and the spoken, the known and the negotiable. It subjected them to reflection, assessment, and interpretation; it made them recognisable. And this shift was part of what gave pregnancy an aspect of crisis, both for the soon-to-be parents and for their families. It was a risky shift: pregnancy rendered the existence of an intimate relationship recognisable, but not its critical details. There was no incontrovertible means of identifying the father, and no certainty that his partner would name him. He or his family might dispute or deny the claim, refusing to be recognised. If the father admitted paternity, but he and his family had few resources, the mother’s family had little hope of laying charges or claiming financial support for the coming child and might wish that he had remained hidden. On the other hand, if he was well off, charges might be laid (a colonial-era invention; see Schapera Reference Schapera1933: 84) but might not be honoured, which might undermine the relationship itself. The recognition of pregnancy was, in other words, a source of numerous potential dikgang, which required careful negotiation between couples and within and between their families. The success or failure of reproducing family lay in the success or failure of these negotiations as much or more than in the pregnancy itself. Success, in this context, meant leaving these dikgang at least partially unresolved. Such a suspension did not necessarily stabilise the relationship, but it left open the eventual possibility of marriage.

After her distraught visit to the neighbours, Mmapula gathered her resolve and set the mechanisms of pregnancy negotiation in motion on two fronts. She asked two of her sons – Moagi and Kagiso – to talk to the girls individually and to find out who the fathers of the children were. They learned that Lorato’s boyfriend was older, and employed, although he was from far away. This information gave Mmapula hope: if the negotiations were handled properly, he would be in a good position to support the child and might ultimately prove to be suitable marriage material. In the meantime, she could assert a claim for compensation. She dispatched her sons to summon him to the yard. Boipelo’s boyfriend, by contrast, was a former neighbour, young and sporadically employed, and his family was not well off. His family’s proximity meant that they could easily have been called or visited, but the matter was not pursued. In fact, the boy’s family was not officially notified about the pregnancy until after the child had been born, although he and Boipelo continued their relationship.

Moagi and Kagiso sought out Lorato’s boyfriend, but he evaded his summons. On a couple of occasions Lorato was visiting him when one of her uncles tried to call him, and she identified the callers. When he still refused to answer, she began to doubt his willingness to take responsibility for the child he had fathered. ‘He said, “I haven’t done anything wrong, why should I be called?”’ she explained, still hurt by the refusal. ‘I told him he couldn’t refuse to speak to my uncles. I asked him if he was refusing the child. He didn’t say anything.’ To her mind, his rejection of the summons suggested a rejection of the potential for kinship that her pregnancy had initiated.

Eventually, Mmapula herself acquired the telephone number of the man’s mother from Lorato and phoned her to report the pregnancy and assert a charge of P5,000 (roughly £425, enough for a couple of cows or a good bull) for ‘making our daughter’s breasts fall’ (for a description of the ‘fence-jumping’ fine, tlaga legora, see van Dijk Reference van Dijk2017: 32). She would have preferred to call the man’s family to her yard, but, given the distances involved and the apparent hesitance of the man to acknowledge the summons, she decided to hedge her bets. The man’s mother agreed to report the charge to her son, but promised little more. The matter was left there.

After that point, the man was sufficiently ‘known’ to Lorato’s family that they would ask after him, talk or joke about him as a potential husband, and allow Lorato to visit him for a few days at a time. Lorato’s mother’s brothers scolded her for laziness with the warning that, once she was married, they would not take her back, insisting that she should develop appropriate work habits now that she ‘had a man’. As the pregnancy progressed, the boyfriend supplied Lorato with ample food, clothes, lotions, magazines, and supplies for the child, reassuring her that he recognised the child as his own. But this mutual recognition remained tentative and tenuous; the man had refused his summons, had never officially visited the yard, and had yet to pay the fine levied on him. If he came to visit Lorato, he generally stayed in his car down the lane and avoided entering the lelwapa. When Lorato went off to see him, Mmapula occasionally asked, ‘And when is he coming to greet us? Tell him we are still waiting to see him. One of these days if something happens to you, we won’t even know where to look for you.’ Boipelo’s boyfriend was similarly circumspect, although he had been a frequent visitor to the yard before her pregnancy. He, too, was tentatively recognised as the father of Boipelo’s child, and Mmapula occasionally asked after him in private; but he was unable to cater to Boipelo’s needs as well as Lorato’s boyfriend, and there were few jokes about Boipelo marrying him.

While pregnancies signify the existence of serious relationships and make them formally known to the families of both partners, they don’t necessarily stabilise the relationship itself. A friend demonstrated this persistent uncertainty to me on the bus home one day. She had been fielding amorous text messages from an older man in the village. ‘Hei! The way this one was after me when I was pregnant!’ she commented offhand, much to my astonishment. She saw my shock and laughed. ‘You don’t know these men. They propose to us when we’re pregnant because they know they don’t have to worry about impregnating us! No chance to get caught!’ I asked what her boyfriend thought about it. ‘O! Why should I tell him? He was too worried to touch me the whole time I was pregnant. What should I do? And anyway he probably has his girls,’ she added with a note of bitterness, thumbing out a reply on her phone. While pregnancy and the fines and negotiations attendant upon it rendered some relationships recognisable, my friend seemed to indicate that it safely concealed others (compare Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2001: 275).

The sorts of recognition conveyed by pregnancy, then, produce multiple dikgang, all of which are addressed in ways that perpetuate ambiguity rather than eliminating it. This ambiguity produces further dikgang in turn – but also leaves open the possibility of kin-making. Among the neighbouring Bangwaketse, Ørnulf Gulbrandsen (Reference Gulbrandsen1986: 22) noted a reluctance to take disputes around pregnancy fines to kgotla (customary court) for formal resolution, despite a tendency to favour the woman’s cause. He explains this paucity of prosecution in terms of guardians’ wariness about their daughters gaining reputations for being quick to sue (ibid.). However, something simpler may be at work: having failed to draw another family into mutual recognition, into the joint process of reflecting on the situation at hand and its implications for their relationships with each other that characterise the negotiation of dikgang, the would-be complainant’s family has already failed to make the would-be defendant’s family into kin. Drawing the family into formal negotiation at the kgotla may produce a final resolution – usually in the form of a payment awarded – but neither the formal process nor the final decision will produce a husband, nor the community of shared risk, ethical reflection and disposition, and continuous dikgang management that makes kin. Indeed, a formal, legal resolution ultimately forecloses those possibilities (a point we will return to in Chapter 12). Where fines and agreements are left ambiguous, processes of mutual reflection and recognition are suspended but can still be pursued – leaving the opportunity of kin acquisition as open as possible, on as many levels as possible, for as long as possible. This open-endedness creates a cycle of conflict and irresolution – potentially extending, as we will see, over the course of generations – and this cycle, I suggest, underpins the production and reproduction of Tswana kinship.Footnote 1

Afterbirth

Her grandmother and mother’s younger sister swaddled the baby boy and took him away before Lorato even knew of his death. At seven months, Lorato had gone into hospital, short of breath and with high blood pressure. The doctors performed an emergency caesarean, but the child’s lungs had begun to bleed, and by the time Lorato woke he was gone.

A small grave was dug adjacent to the room in which Mmapula and most of the children slept, virtually in the short pathway that led into the lelwapa past the outdoor kitchen. It was sealed with cement. It was some time after I had returned in 2011 that I was told where the grave lay, and I was surprised when I heard: it was a space where old plant pots and dirty buckets were left, where large cooking pots were tipped up to dry, and where the children played freely, often running over the top of it as they came charging around the edge of the house. But it needn’t have surprised me. Kelebogile’s first child, lost at roughly two years old, lay under the grandmother’s room next to it, buried there before the addition had been built. ‘That way she’s close to her mother in case she needs anything,’ Lorato said, explaining her own child’s burial by way of her mother’s sister’s lost girl.

Boipelo had been delivered of a baby girl shortly afterwards. Lorato and Boipelo were both taken to be motsetse – a term for new mothers in confinement – and both stayed with the baby in a room they shared in Mmapula’s yard. Neither of them was meant to move out of the house or yard for a month. Neither was permitted male guests, and neither could visit her boyfriend nor receive him at home. There were no special constraints on the girls’ movement outside the village, but while they were in the village they were prohibited from setting foot beyond the gate. Lorato was uncertain about the reasoning for this edict, but she connected it loosely to the prevention of drought and harm to cattle, and to the avoidance of risk to people who might cross her path – as well as avoiding risks to herself, Boipelo, and the child with whom they were confined. It was also intended to protect against witchcraft and illness, which were especially marked risks given the loss of Lorato’s baby (see Lambek and Solway Reference Lambek and Solway2001 on dikgaba, illnesses that afflict children and are linked to jealousy and witchcraft among relatives; see also Schapera Reference Schapera1940: 233–4; and, on ritual avoidance more broadly, Douglas Reference Douglas2002 [1966]; Turner Reference Turner2017 [1969]).

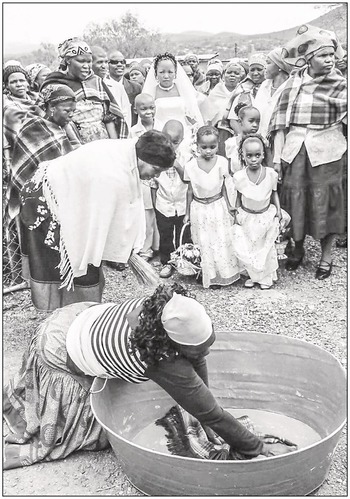

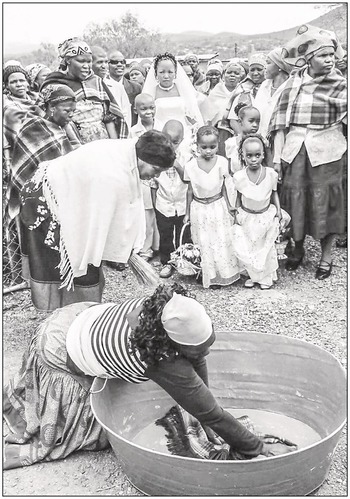

In this sense, a woman’s movement out of the yard and around the village after the birth – or loss – of a child presents a further and slightly different series of dangers, or dikgang, to be contained. And it is her natal family that has a special responsibility in containing them, especially where family-linked witchcraft is implicated. Confinement helps contain these risks in part by blocking and reversing the recognition that a woman’s pregnancy brings upon her and the relationship that produced it; it renders her and her child temporarily invisible, inaccessible, and their status unknown. Even old friends who had given birth while I was in the village suggested that I visit them at the clinic before they were sent home, ‘because you know how these elders are about witchcraft’.Footnote 2 The re-emergence of new mothers and babies into public spaces after their confinement is also a carefully managed, gradual process of controlling what can be seen, heard, spoken, or known, by whom and how. When Boipelo’s baby was first allowed out into the yard, her six-year-old brother Thabo remarked to the little girl, indulgently, ‘Ga re go itse, akere!’ – We don’t know you, do we? – as if to introduce himself, while distancing her from the risks that relational recognition might create. Parties are often held for children when they turn one year old, although only family and friends attend instead of the large public attendance expected at most other domestic celebrations. At the end of her confinement, Lorato’s maternal grandfather, Dipuo, instructed her to wash her feet, and then led her around the village silently, well before anyone was awake and might see them. He sprinkled her washing water before her, as if to contain the traces she might leave, enabling her emergence by concealing it. Containing recognition cannot eliminate dikgang, but it carefully circumscribes the relational sphere in which they may emerge.

Of course, the dikgang emerging from pregnancies are not confined to fraught dynamics of recognition around establishing paternity through fines or managing the dangers posed to and by postnatal women. They also emerge around the provision of care to the newborn child – specifically, the father’s recognition of responsibilities to contribute, and the recognition conveyed on him in turn. Lorato’s boyfriend had provided well for their baby’s needs and Lorato had a generous stockpile of clothes, nappies, toiletries, nutritional supplements, bathtubs, and other supplies stashed in her room before she lost the child. She spoke often and with deep fondness of the time she had visited her boyfriend and he had given her a sum of cash to buy whatever she needed for the baby from the shops. To hear Lorato tell it, pregnancy had been a time of plenty for her; she had had comparatively few responsibilities, had been accorded a degree of freedom to visit her boyfriend, and had been handsomely supplied with clothes, food, magazines, mobile phone units, and virtually anything else she desired – as well as everything that would be needed for the baby. She sometimes joked that it was the best job she had ever had – and, unlike other jobs, she hadn’t been expected to provide tokens of respect and support to her malome or grandmother, but could keep everything for herself.

While the gifts Lorato’s boyfriend had provided were not official gestures in the way that gifts presented in anticipation of marriage are (as we will see later), they did indicate a potential willingness and ability to provide for the care of Lorato and their child (compare Klaits Reference Klaits2010: 43) – a contribution to Lorato’s natal household that marked his acceptance of responsibility for her and a willingness to behave like kin, in keeping with his level of income. In many respects, the gifts were his one gesture towards recognisability; and they were a critical dimension in the family’s recognition of him, tentative as it was (compare similar allowances on the part of family in Schapera Reference Schapera1933: 80). At the same time, they did not stand in for a formal acknowledgement of the family’s claims on him, and – coming as they did through Lorato – they carefully evaded the sort of recognition those claims would establish over him and the ongoing cycle of negotiations they would precipitate. They were gifts given to Lorato, not debts paid or contributions made to her family; as such, they evaded dikgang. By comparison, Boipelo’s sporadically employed boyfriend had provided her with little or nothing prior to their child’s birth – which exacerbated his effacement at home.

‘Actually, that’s why I didn’t buy a stroller,’ Lorato added. I didn’t follow. She explained that her boyfriend had wanted them to buy a stroller – an expensive and uncommon item among families in the village. ‘He was insisting but I refused. How can I have a stroller, Boipelo having nothing?’ She explained that two of her mother’s younger sisters had faced a similar situation at the births of their own first children. ‘When Kelebogile was having her first child,’ she explained, ‘Oratile got pregnant about the same time. Kelebogile’s boyfriend was working and gave them everything. But Oratile was younger, the boyfriend was a bit useless, he wasn’t working or anything. So they were struggling at home. Kelebogile lost her first child when she was maybe a year or something. She gave everything, all the things the boyfriend had bought, to Oratile.’ The grudging, subtly bitter attitudes towards their mutual responsibilities, which often provoked squabbles between the two sisters (as we saw in Part II), suddenly took on a new dimension.

These legacies had re-emerged for scrutiny in Boipelo’s and Lorato’s situation, and Lorato was outlining yet more careful balances to be struck. On the one hand, she had to make clear her boyfriend’s willingness and ability to provide for her, allowing her family to recognise it (and him) without making a show; on the other, she had to conceal this support in order to minimise her continuing responsibilities to contribute to her natal household, and to keep demands on her partner reasonable, sustainable, and primarily oriented towards herself. But Lorato also had to demonstrate a reflexive awareness of how her newly acquired resources might have an impact on her relationship with Boipelo and Boipelo’s self-making trajectories, and of how her choices over what to do with those resources might echo and reflect upon the past dikgang of her mother’s sisters. After the loss of her own child, Lorato gave everything she had stockpiled to Boipelo, just as Kelebogile had to Oratile.

I noted several changes in Lorato after the loss of her child and her confinement. Most notable was her attitude towards her younger cousins. She had always been friendly, playful, and at ease with them, like siblings; but now she scolded them and spoke sharply, gruffly sending them on errands or putting them to work. Indeed, her mother’s brothers and sisters, and her grandparents, now chastised her when she was too familiar with them. When I mentioned it, she replied with conviction: ‘Ke motsadi [I am a parent]; I can’t just play with children any more.’ Boipelo, too, took on a new tone of authority; she was preoccupied with finding paid work and left her sister with most of the childcare responsibilities. Both women spoke, dressed, and behaved differently, and they related differently to those with whom they had been most familiar. They had come to be recognised as parents, and as women.Footnote 3

Thus, while pregnancy and birth may leave considerable ambiguity in relationships between new parents, and between their families, in one respect they are unambiguous: they reorganise a woman’s relationship to her natal family. This reorganisation begins in pregnancy negotiations but is perhaps most marked in the management of dikgang after birth. Neither the father nor his family has any formal part to play in taking on or ameliorating these dikgang, and there is little negotiation involved. If anything, he and his kin are explicitly excluded. This is the case even for married couples: with their first child, women will generally return to their natal homestead for confinement after the birth (which is increasingly conducted in a clinic or hospital). I suggest that this unilateral responsibility for the risks of birth and their containment works primarily to produce and reproduce kinship between the woman, her child (if there is one), and her natal family, who will be important figures in her child’s life whether she has married and moved away from them or not – her brothers especially, but also her sisters and parents.

Pregnancy also makes a significant difference to women’s personhood, marking a key success in making-for-themselves. Even if the woman cannot carry the child to term, she nevertheless becomes motsadi (parent) and mosadi (woman) by virtue of her pregnancy. In Setswana, the verb for being pregnant is go ithwala: the verb go rwala, to carry or bear, cast in the reflexive – so that it is something one does to oneself. To conceive or be pregnant, in other words, is to carry oneself or to bear oneself, as well as one’s child – a description that alludes richly to its importance in a woman’s self-making. This new status, of course, is perfected gradually and entails a long learning curve: Lorato had to learn to distance herself from the other children of the yard, to treat and speak to them differently. While both she and Boipelo stumbled and fell over some of these new expectations, they did not cease to be women and parents as a result; pregnancy conferred that role on them, irreversibly. Their pregnancies were incontrovertibly recognisable in the women’s bodies, which publicly marked their sexuality, fertility, and new responsibilities of care. And the dikgang generated by this recognisability – from questions of how to care for the child to claims against boyfriends and the containment of risks posed by postnatal bodies – were all managed within and by their natal family.

Notably, the Legaes spoke of neither Boipelo’s nor Lorato’s boyfriend as motsadi (parent) or monna (man) due to his having fathered offspring. Only Lorato’s boyfriend was identified as monna (man), with explicit reference to his potential marriageability. Rather than pregnancy – in which men are only indeterminately recognisable, and from the dikgang of which they are excluded (and may exclude themselves) – it is marriage that seems to confer on men the recognition that enables them to reproduce and realign kin relations. But reproducing kinship through marriage is also a fraught and uncertain process – as Kagiso’s attempt to marry showed, which I turn to next.