A Transcript

Tsutsumi Otokichi was called. He stated: – I was employed doing work on board the Yamashiro-maru. On the night of the collision I was forward beside the port bow rail. I cannot remember who was with me, but I was standing there looking. I do not know how many people were there. I remained there about half an hour. I have no idea what time it was.

The President Was it daylight or had darkness set in?

Witness It was after darkness had set in.

The President In that position, what did you see?

Witness I was expecting to see Yokohama.

The President But what did you see?

Witness Nothing, but the lights of fishing boats.Footnote 1

Tsutsumi Otokichi appears nowhere else in documents I have gathered concerning the Yamashiro-maru’s career. It’s probable, indeed, that he would have remained a nameless actor in this history had it not been for the events of Tuesday, 21 October 1884. On a dark evening, with rain threatening – this according to the testimony of Ishikawa Shinobu, second mate to the captainFootnote 2 – the Yamashiro-maru ploughed at full speed into the starboard side of an iron-hulled, three-mast sailing ship, the Sumanoura-maru (715 tons), as the former approached the entrance to Tokyo Bay.Footnote 3 Fatally breached with a gash of up to thirty-five feet (10 m) in length, the Sumanoura-maru was steered into the shallow waters of nearby Kaneda Bay, where it sank without loss of life. The Yamashiro-maru was damaged and would be temporarily decommissioned.

That the Sumanoura-maru was owned by Mitsubishi – in an earlier life, as the Stockton-on-Tees-built Bahama, the ship had been a blockade runner for Confederate forces during the US Civil WarFootnote 4 – only added to the drama of the collision. In the autumn of 1884, Mitsubishi was engaged in a battle almost to the death with the KUK, owners of the Yamashiro-maru, over which company could offer the fastest and cheapest passage between Kobe and Yokohama – the route that the Yamashiro-maru had been steaming on the evening of the crash.Footnote 5 For this reason, I assumed, the surviving transcript of the subsequent proceedings in the Marine Court of Inquiry, opening six days later on 27 October, would offer revealing insights into a business rivalry which had entertained the press and concerned the government in equal measure (see Figure 1.5). Indeed, the fact that the proceedings had been meticulously transcribed and printed in the Kobe-based Hiogo News, today preserved in the Kobe City Archives, indicated the high level of interest the case had generated among the foreign merchant community in the city.

I was wrong in those particular assumptions: little of intrigue or rivalry was revealed in the court of inquiry’s transcript. But two other points did emerge from the columns and columns of tiny print. First, the source offered the rarest of brief insights into the daily lives of the ship’s working crew or temporary contractors – men like Ishikawa Shinobu and Tsutsumi Otokichi respectively. Here, even in a few sentences, was a genre I had never accessed for the Wakamiyas and Kodamas of the Yamashiro-maru’s steerage decks, namely a mini ego-document with the first-person singular at its heart. Here lay a possibility, even momentarily, to hear beyond the ‘official’ voice of the ship, as would later be represented by Chief Engineer Mr Crookston when he acted as interlocutor for the Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser reporter in Hawai‘i (see Chapter 6).

These, for example, are the opening words spoken by one Kawashima Sukekichi, an ordinary seaman:

I have been on board the Yamashiro from the 16th inst. [16 October] I joined her at Yokohama. I have been only one voyage in the Yamashiro. I have been at sea since the 15th year of Meiji.Footnote 6

It’s not much to go on, admittedly. But we may presume from this autobiographical record that Kawashima was one of the 1,570 seamen employed by the KUK in 1883–4 through the agency of the Seafarers’ Relief Association (Tokyo);Footnote 7 that he had worked for the company since its founding in 1882 (Meiji 15); and that his transfer to serve as an ordinary seaman on the Yamashiro-maru, then the KUK’s flagship steamer, therefore marked something of a promotion in his fledgling career.

As for his actual testimony, Kawashima stated:

On the night in question I did not see either the barque [Sumanoura] or her lights. I was standing at the starboard rail forward, looking towards the sea. I did not see anything. I did not see anything after the collision, as I went aft to get the boats ready.

Such denials were to be expected: those on board the Yamashiro-maru, including especially the ship’s captain, Mr Steedman, claimed to have seen nothing on the night of the crash. This reinforced Steedman’s insistence that the fault must lie squarely with his Sumanoura-maru counterpart, Mr Spiegelthal, who, he claimed, had failed to properly illuminate his vessel’s port and starboard lights. Whether or not Kawashima saw anything is therefore unclear; but in toeing the company line under legal caution, he was also proving himself to be a loyal employee of the KUK.

The second point which emerged from the Hiogo News transcript concerned the nature of record-keeping. Shorn of their courtroom context, the testimonies of Kawashima, Ishikawa or Tsutsumi offer no indication as to what language the three men were speaking. Only when we note the names of the court’s officers – Mr Geo. E. O. Ramsay, Esq. (President), Captain J. F. Allen (commanding the Lighthouse Department steamship Meiji-maru) and Mr E. Knipping, Esq. (Meteorological Department, Tokyo) – does it become clear that the testimony of the Japanese actors had to be translated into English for the benefit of the principal players. Thus, the role of the unnamed Japanese-to-English interpreter was key to the production both of the court record and of the transcript I was reading in the English-language newspaper.

Yet the interpreting abilities of this key linguistic broker were questionable.Footnote 8 One of the principals to raise particular objections was Robert W. Irwin, future owner of Joseph Strong’s Spreckelsville painting, who stood before the court in his capacity as foreign manager for the KUK.Footnote 9 Two years previously, Irwin’s marriage to Takechi Iki had been the first non-Japanese/Japanese union to be officially recognized by the Meiji government. Irwin seems to have communicated with his wife at least partly in Japanese.Footnote 10 It was presumably on the basis of this ability that he challenged the court of inquiry’s interpreter during crucial evidence from a witness who had been aboard neither the Yamashiro-maru nor the Sumanoura-maru, and who might therefore be expected to speak with a higher degree of impartiality. President Ramsay had previously ruled that the interpreter be left uninterrupted in his work, but now Irwin sought clarification:

Mr. Irwin I understood you to say at that time that you would permit a written memorandum.

The President Yes, passed in silence, but I think it was arranged that there would be no interruption, because the work is very distressing to the interpreter of the Court. He does his best, and for myself I am satisfied with it.

Mr. Irwin But, take for instance, a serious question of mis-interpretation?

The President Then the point will be this. I do not think any difficulty will arise; because, although this enquiry has been exhaustive, at the present day it remains in a small space. It is simply in reference to the [Sumanoura’s] lights – and the lights only.Footnote 11

The exchange is at one level banal – the type of procedural question about the admissibility of evidence played out in courts across the world and across the centuries. But that banality is exactly the point. Irwin was seeking to confirm the accuracy of the interpretation and thereby the precision of the recorded facts; together with the president and the interpreter, he was co-crafting the factual record and thus engaged in the first moment of what Michel-Rolph Trouillot terms ‘the process of historical production’. This moment of fact creation, or the making of sources, is followed by three others, to which I shall return: fact assembly, fact retrieval, and retrospective significance – or, respectively, the making of archives, the making of narratives, and ‘“the making of history” in the final instance’.Footnote 12

The question of interpretation was also raised at a more abstract level. In his cross-examination of Tsutsumi Otokichi, President Ramsay asked if the witness had seen any coloured light:

Witness I had not seen any coloured light. I did not see the form of any foreign built ship.

The President Had a coloured light appeared, would you have noticed it?

Witness I do not know any light at all – or rather I do not know such light. Except small boats’ lights I did not see any lamp lights.

The President What was the colour of those small boat lights.

Witness All small, red lights. All the lights burning in fishing boats were small, red lights.

Thus far, the testimony reads as we might expect: Tsutsumi denied that he had seen anything resembling the green starboard light of the Sumanoura-maru, or indeed the looming shape of a foreign-built ship. But at this point the Yamashiro-maru’s captain intervenes and asks an apparently bizarre question, one which the interpreter – in a rare moment of recorded speech – feels necessary to explain:

Captain Steedman Will you ascertain what is this man’s idea of colour?

The Interpreter You must understand that Japanese call all lights at a distance red, even though they may be only a yellowish white – not by any means scarlet.

The President tested the witness by giving him red and white scraps of paper to separate, the witness selecting the red pieces.Footnote 13

The exchange seems tangential at best to the issue of why two ships collided.Footnote 14 But the point here is not whether ‘Japanese’ did actually perceive colours differently;Footnote 15 rather, it’s that the court’s president found a quick way to dismiss the ‘idea of colour’ as an explanatory factor in Tsutsumi’s testimony. If, for the purposes of a thought experiment, we were to consider this ‘idea’ an example of Indigenous knowledge, then the court transcript records a process in which such knowledge was measured against an apparently objective scale – red and white scraps of paper – and then made to be commensurate.Footnote 16 That is, ‘red’ was defined according to the standardized norms of an English-language courtroom, such that the nuances both of the vernacular language and of vernacular ways of seeing were edged out of the historical record. The witness himself, in being forced to make a binary choice in silence, was rendered voiceless.

In this chapter, I explore such edges of the historical record, and the silences produced in their recording. I question the commensurability of apparently similar concepts across very different historiographical contexts. I try to interpret from scraps of paper. But most of all, I am interested in the view and the sounds of the outside – in what can be seen from the bow rails, and what historians might miss in the archival dark.

Outside (1): Hawai‘i State Archives

The retrieval of facts from the archive, or what Trouillot calls the third moment of silences entering the production of history, demands a level of scholarly alertness that is sometimes difficult to maintain while battling jetlag. Such, at least, was my experience during a two-week stay in Hawai‘i in March 2013. On this particularly somnolent Friday morning, I am trying to retrieve more facts about how plantation life may have been experienced by the labourers themselves. I have a hunch that the career of a man called Fuyuki Sakazō may help me in this endeavour.Footnote 17 Fuyuki – he of my initial trip to Kapa‘a (Chapter 1) – left for Hawai‘i on the government-sponsored programme’s ninth crossing, in September 1889. As I begin to size up his life, I would like to imagine him standing on the Yamashiro-maru’s forward decks, looking towards the open seas as his pre-migration life receded into the distance. Ideally, though, I would like to do more than imagine: I am here in the Hawai‘i State Archives looking for any scraps of paper which might figuratively reveal his own ‘idea of colour’, his own way of seeing his new world. But, once again, the only traces I can find have been authored by the bureaucrats, the agents, the inspectors.

I have on the desk yet another handwritten letter from Robert W. Irwin. This one, marked ‘confidential’, is dated 8 May 1890 and addressed to Interior Minister Lorrin A. Thurston (1858–1931). Irwin begins by reporting on the incoming Japanese government’s seemingly perennial complaint about the categorizations of East Asia labourers: ‘the new men [that is, ministers] have formed the opinion that there is a tendency in Hawaii to treat the Japanese from a Chinese standpoint, and to class Japanese and Chinese together’.Footnote 18 He cites the new Hawaiian Constitution of 1887 (the so-called Bayonet Constitution, forced upon King Kalākaua by Thurston and others) as an object of Tokyo’s concern, in particular the articles limiting the suffrage to male residents ‘of Hawaiian, American or European birth or descent’.Footnote 19 He describes the ‘soreness’ of some officials ‘over the exclusion of the Japanese from the [Hawaiian] electoral franchise’, and his worry that this might negatively affect the emigration programme. In other words, Irwin argues that the Bayonet Constitution’s bracketing of Japanese and Chinese as equally ineligible for the franchise (and thus, by implication, equally uncivilized) might provoke the Meiji government into reviewing a programme which Irwin took to be self-evidently in Hawai‘i’s interests. But then he closes on an optimistic note – albeit with a comically awkward turn of phrase: ‘I believe that I can take care of this political question and can have it postponed; and considered hereafter upon it’s [sic] own merits; leaving the emigration a purely industrial question to stand upon it’s [sic] own bottom.’Footnote 20

Grateful to have been jolted from my torpor by anything remotely scatological, I make a pencilled note of an adjective I have now seen more than once in the context of Japanese migration, namely industrial. The ‘industrial partnership’ hailed by the Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser in July 1885 flickers at the back of my mind, as does a proprietary claim Irwin would make in 1893, when, in the wake of the Hawaiian monarchy’s overthrow, he called the government-sponsored programme ‘our great industrial Emigration Convention’.Footnote 21 On the one hand, the word gives historians a sense of the scale of Irwin’s and the planters’ ambition, namely that sugar would transform Hawai‘i as it already had the Caribbean islands. (While on this trip, I have been reading Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power, with its description of the Caribbean sugar plantation as ‘an industrial enterprise’.)Footnote 22 But when set alongside the history of the Hawai‘i-bound emigrants from Japan, the adjective ‘industrial’ also offers a different perspective on a long-running historiographical debate about the so-called preparedness of the mid nineteenth-century Japanese economy for the country’s subsequent industrialization.

One key argument, articulated in a 1969 essay by Thomas C. Smith (1916–2004), focused on the ‘readying’ of the rural population for the transition from agriculture to industry through the practice of part-time, non-agricultural work. The essay began:

By-employments, one may suppose, tend to ready preindustrial people for modern economic roles since they represent an incipient shift from agriculture to other occupations, spread skills useful to industrialization among the most backward and numerous part of the population, and stimulate ambition and geographical mobility.Footnote 23

To flesh out these general observations, Smith offered a granular study of one ‘county’ (saiban 宰判) in the south-east of the Chōshū domain, itself located just west of Hiroshima and today known as Yamaguchi prefecture. Based on an extraordinary economic survey conducted by domain officials in 1842, Smith identified Kaminoseki county as having been characterized by a particularly high level of by-employments, ranging from salt-making in Hirao village to the income-generating opportunities offered by the marine transportation industry in Befu village. Meanwhile, in the eponymous port-town of Kaminoseki, where the Inland Sea narrows to a fast-flowing corridor around 100 metres in breadth, trade accounted for a very high proportion of non-agricultural income, and the same was true on the opposite side of the Kaminoseki straits in the port-town of Murotsu.

When, at the beginning of my doctoral studies, I had first read Smith’s essay, my interest had been spurred by the coincidence of my having worked and lived in what is today Kaminoseki town – that is, Kaminoseki and Murotsu ports, plus some outlying villages and islands. The town’s obvious late twentieth-century stagnation spoke to one general critique of Smith’s speculative ‘connection between the development of by-employments in the eighteenth century and modern economic growth’ – namely, that there was often no straight line connecting proto-industrial growth with industrial growth.Footnote 24 Perhaps, in general terms, an argument could indeed be made that ‘Japan’s industrial labor force expanded in large part by the recruitment of workers from farm families who, thanks to by-employments, brought to their new employment usable crafts, clerical skills, and even managerial skills’; but this wasn’t the story in the shrinking villages and towns of Kaminoseki county itself.Footnote 25

Moreover, Smith’s hypothesis that by-employments stimulated ‘ambition and geographical mobility’ focused only on the phenomenon of domestic migration within Japan. It thus overlooked the most interesting aspect of Kaminoseki’s late nineteenth-century history, namely overseas migration on an extraordinary scale. And this, in short, was why I was engaged in a soporific search for any details which might facilitate a basic narration of Fuyuki Sakazō’s life. That Fuyuki came from Murotsu, in the same Kaminoseki county studied by Smith, suggested that his employment history, spanning Japan and Hawai‘i, might offer new insights into the hitherto understudied transpacific dimension of Japan’s emerging transition from agriculture to industry across the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I hadn’t yet articulated it in this way, but on that slow morning in the state archives, these were a few of the thought associations provoked by the adjective ‘industrial’.

Abruptly, my daydreaming is broken by brass chords and the voice of a female singer. Looking up from Irwin and Thurston and bottoms, I remember that on Friday lunchtimes the Royal Hawaiian Band performs for tourists.Footnote 26 So I down tools, leave the archives’ air-conditioned reading room for the warmth of an overcast day, and stroll past the rear of ‘Iolani Palace to where the musicians are playing.

The band’s members, all in white, are arrayed under the canopy of a great monkeypod tree, while around seventy tourists, mostly middle-aged and dressed in shorts and tucked-in T-shirts, sit on metal fold-up chairs. After a set or two the MC, a Native Hawaiian man wearing a scarlet Aloha shirt, again takes to the microphone to explain that the next song dates from the very darkest chapter of Hawaiian history. The overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in January 1893, he says, was plotted by the sons of missionaries with the connivance of the then-US minister. Deprived of their queen, their land, their very nationhood, the Hawaiian people protested, and in that moment of protest, the composer Eleanor Kekoaohiwaikalani Wright Prendergast (1865–1902) wrote ‘Kaulana Nā Pua’ for the Royal Hawaiian Band sitting here today. The band, which the leaders of the coup tried to disband, had refused to be cowed, and so the very playing of Prendergast’s song constituted an act of resistance.

I don’t have a translation of Prendergast’s song to hand. I will find one later that evening, in Haunani-Kay Trask’s essay, ‘From a Native Daughter’:

But as the singer begins to perform, a man in the audience quietly rises to his feet, doffs his cap and holds it to his chest. Standing behind him, I cannot see what his gesture may represent – regret? an apology? a sign of respect? – but I find it unexpectedly moving.

Walking back to the state archives past great banyan trees re-rooting themselves into the land, I am unsure whether and to what extent a migrant labourer such as Fuyuki Sakazō might be pertinent to this history of monarchical overthrow. That he may have been imbricated in the historical context was implied by the May 1890 letter still on my desk: Fuyuki was one of thousands recruited by Irwin; Irwin was selling the emigration programme to Thurston as in the interests of the Hawaiian government; and Thurston, in addition to having agitated for the imposition of the 1887 Bayonet Constitution, would also be a rebel ringleader during the 1893 coup.

In the meantime, the act of leaving my desk to hear a song had revealed something more fundamental about historical production. The traditional ‘sound of the archive’, as Wolfgang Ernst has suggested, is silence – an absence of voices, a negative sound which conversely becomes part of the archive. The scribbling pencil, the nasal snort, the rustle of turning pages: these para-archival elements may be taken to constitute what he calls the reading room’s ‘sonosphere’.Footnote 28 There are no songs in this sonosphere. Yet the melodies of the Royal Hawaiian Band drifting in from outside highlighted an act of exclusion embodied in the archive. Here, in the enveloping quiet, I could retrieve facts which helped me reconstruct Irwin’s narrative of the world: his idea of plantation labour as an ‘industrial’ project, for example. But if I could not do the same for Fuyuki, this was because I was looking in the wrong place, hindered by the second moment in Trouillot’s analysis of historical production, namely the moment of fact assembly (or the making of archives).Footnote 29 Of course there would be nothing revealing of Fuyuki’s worldview here. The narrative colours were predefined by the agendas of the actors I was reading: actors who spoke to and for Fuyuki, thus rendering the migrants’ choices and decisions silent.

To make amends for the gaps in the particular fact assembly that had given rise to this set of records on my desk, I would figuratively have to step outside: not to abandon the written records per se, but to read them according to a different set of definitions, ones articulated by the labourers themselves. Inspired by the genre if not at that point the meanings of Prendergast’s composition, I decided to look in more detail at the words which the plantation labourers sang in their transplanted work songs from western Japan. The canefield songs, I shall argue in this chapter, did more than express the workers’ frustrations, their shattered expectations, their wry observations on conditions at individual plantations such as Spreckelsville. They also voiced a vernacular worldview no less significant to historians’ understanding of nineteenth-century economic transformations than Robert W. Irwin’s (or, indeed, Thomas C. Smith’s) understanding of ‘industry’. In particular, two images in the lyrics – the human body and the idea of circulation, itself a pregnant but understudied metaphor for global historiansFootnote 30 – spoke to the intellectual and physical landscapes from which a migrant like Fuyuki Sakazō had departed. Stacking up a series of meanings associated with the term ‘circulation’ in nineteenth-century Japan, I ask how these landscapes, or more accurately seascapes, shaped Fuyuki’s understanding of labour.Footnote 31 How might he have conceptualized his own place in a world of circulating goods, ideas and people? And how might historians interpret up from these scraps of songs to frame the historiographies of ‘industry’ and the related term of ‘industriousness’ in new ways?

To answer these questions, I must shortly depart the Yamashiro-maru. Without the ship sailing transpacific sea lanes, Fuyuki’s career would have been impossible. But to make sense of that career, we need other sounds, other sources, and other archival starting points.

Labouring Bodies in Circulation

Following the Yamashiro-maru’s initial passage to Hawai‘i in 1885, the ship did not return to the kingdom for another four years. Instead, after the KUK and Mitsubishi merged to become the Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (NYK) in October 1885, it ran the more profitable Kobe–Yokohama line – during which time it sped the young Yanagita Kunio off to his adult life (see Preface). Only in September 1889 did the ship resume carrying migrants on the government-sponsored programme. Over the next three years, it crossed to Honolulu eleven times in total, transporting more outgoing Japanese than any other NYK vessel. On the passage back from Hawai‘i, too, the NYK ships carried Japanese labourers, though in lower numbers. These were men and women who had either completed their three-year contract or who were returning to Japan after a second plantation contract. Included in the latter group was Wakamiya Yaichi, who departed Honolulu on the Yamashiro-maru for his home village of Jigozen, Hiroshima prefecture, on 6 December 1892.Footnote 32

By that time, some of the work melodies from the migrants’ pre-Hawaiian lives had become part of the plantation soundscape. Reaching their hands into the cane plant’s one-to-two metre long, painfully sharp leaves (holehole in Hawaiian) to pick out dead matter, the labourers kept their spirits up with songs (bushi in Japanese). Like the largest number of government-sponsored migrants, the melodies of these holehole bushi ホレホレ節 came from Hiroshima, perhaps from the songs that farmers sang as they hulled rice.Footnote 33 By contrast, the lyrics grew out of the labourers’ new lives on the islands and expressed the full gamut of emotions about the plantations’ often lamentable working conditions – punning, for example, on the words for cane (kibi) and harsh (kibishii).Footnote 34 One such first-generation holehole bushi reads:

After one or two contracts | |

Kaeranu yatsu wa | The poor bastards who don’t go home |

Sue wa Hawai no | End up in Hawai‘i |

Kibi no koe | Fertilizer for the sugar cane.Footnote 35 |

Here punning on the homonym koe, the song’s last line can mean ‘fertilizer for the cane’ but also ‘voices of the cane[fields]’. The singer thus articulates a fear that they will die without ever returning to Japan, and that their body will end up as fertilizer, their voice silent in the earth. And yet, the words were performed, not read: depending on speed, gesture and other paralingual elements in harmony with the music, they could be humorous, regretful, salutary or angry. Whichever way, to sing was to defy the fate of silence.

As these lyrics demonstrate, the labouring body offered migrants one framework for interpreting their Hawaiian experiences. Here, the meanings were rendered especially earthy by the fact that koe refers to night soil – to fields fertilized by human urine and faeces. Such a relationship between the body and work appears in another holehole bushi sung in the 1890s and published by a Hawaiian-based Japanese journalist in 1900:

Mīru e nagare | To the mill. |

Kibi wa furomu de | The cane drifts down the flume |

Wagami wa doko e | As for my body – |

Nagaru yara | Where will it drift?Footnote 36 |

Here the key word is ‘drift’ (nagaru 流る), a character whose left-hand radical denotes water. The meanings of nagaru range from ‘flow’, to ‘pour’ (including the transitives, namida o nagasu, literally ‘to pour tears’, or ase o nagasu, ‘to pour sweat’), to – in combination with other characters – ‘current’ or ‘circulation’. And it is in this imagination of the circulating, drifting, sweating and even crying body that we can posit one vernacular interpretation for how migrant labourers crossing from Japan to Hawai‘i might have imagined their place in the world.Footnote 37

In fact, the relationship between work and circulation in mid nineteenth-century Japan had been visualized a generation prior to the government-sponsored programme in a popular woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada 歌川国貞 (1786–1864). Entitled ‘Rules of Dietary Life’, it depicted a portly, seated man in cross-section, thus offering the viewer a glimpse of the body’s internal organs at work (see Figure 3.1).Footnote 38 And work was the operative term. In the print, dozens of miniature male labourers, dressed in blue uniforms, busy themselves stoking the fires under the spleen’s huge cooking pot, or shovelling mushy food into wooden barrels which they then carry from the warehouse of the stomach to the millstone of the liver. As they work, they chat in a patois that the print visualizes in the native hiragana script, in contrast to the more formal medical explanations written in Chinese characters. Parallel to the oesophagus, for example, four labourers are waving huge fans marked with the character ‘breath’ in order to aerate the lungs. One, bent exhausted over his fan, complains to his co-worker that he is at breaking point. His observation puns on the word hone, referring both to the fan’s ribs and to the labourers’ own bones:

Figure 3.1 Utagawa Kunisada, ‘Rules of Dietary Life’ (Inshoku yōjō kagami 飲食養生鑑), c. 1850.

‘I’m beat! Shouldn’t we take a short break?’

‘Let’s keep giving it our best,’ his co-worker says, punning once more on hone by using the idiom ‘great effort’ (hone oru 骨折る), ‘and then we can rest.’

In the body’s other lung, two colleagues, still fanning with all their might, grumble to each other, ‘What’re we gonna do if this guy doesn’t work?’

As if nineteenth-century Oompa Loompas in the body’s astonishing factory, the four men know that theirs is part of a bigger effort. If they do not work, the heart will not pump; if the heart does not pump, the food will not circulate; if the food does not circulate, the body will not function. Thus, circulation was key to good health, as Japanese doctors had begun to argue from the late seventeenth century onwards. This belief was a departure from Chinese medicine, which maintained that poor health was caused by depletion of vitality (Ch. qi, Jp. ki 気) from the body, and that such depletions could be minimized by avoiding wasteful effort. Instead, as Shigehisa Kuriyama has argued, Japanese doctors came to see the problem of ill health not in terms of depletion from the body but rather the stagnation of vitality in the body. Stagnated vitality, in the form of impeded internal circulation, would cause ‘congestions, congelations, accumulations, hardenings, knots’.Footnote 39

What was true of the corporeal realm applied also to the economic. In Principles for Nourishing Life (Yōjō kun 養生訓, 1713), the Confucian scholar Kaibara Ekiken 貝原益軒 (1630–1714) had argued that the stagnation of wealth was to be avoided at all costs:

If the flow of material force (ki) through heaven and earth is stopped up, abnormalities arise, causing natural disasters such as violent windstorms, floods and droughts, and earthquakes. If the things of the world are long collected together, such stoppage is inevitable. In humans, if the blood, vital ether (ki), food and drink do not circulate and flow, the result is disease. Likewise, if vast material wealth is collected in one place and not permitted to benefit and enrich others, disaster will strike later.Footnote 40

By the mid nineteenth century, this idea that collection would lead to disaster was commonplace. In the aftermath of the Ansei Edo earthquake (1855), for example, one popular print depicted an unsympathetic catfish – long a symbol of seismic activity in Japan – forcing a merchant to vomit gold coins onto gleeful labourers gathered below him.Footnote 41 The print was a visualization of Kaibara Ekiken’s broader argument within the specific context of the shogun’s capital: stagnated flow, or the Edo merchants’ unnatural hoarding of money, had caused a natural disaster.Footnote 42 Other intellectuals in late-Tokugawa Japan similarly made the case for the relationship between circulation and economic health. The words used for ‘circulation’ differed by author, but the reasoning was always the same: the flow of money generated by commerce was as important to economic prosperity as the flow of blood to human well-being.Footnote 43

This association of flowing commerce with economic prosperity would have made good sense to anyone growing up in Fuyuki’s home town of Murotsu.Footnote 44 Located in the south-eastern tip of the Chōshū domain, Murotsu was a key regional port by the 1840s – second in importance only to Kaminoseki, on the other side of the straits. Murotsu’s importance and success were reflected in the occupational and income profile of its households. In what Chōshū administrators termed the ‘port district’ (ura-kata 浦方), there were 228 households in 1842, almost double the number from the mid eighteenth century. Ninety-eight per cent of these port households were non-farmers and the district’s reported income was entirely non-agricultural. Thus, to an even greater extent than in Wakamiya Yaichi’s home town of Jigozen, a day’s sail further east, the residents of Murotsu’s port district made their money not from farming-related activities but rather from the growing importance of interregional trade in mid–late Tokugawa Japan (trade accounted for 72 per cent of the port-district’s reported income). Located on the Inland Sea’s main east–west shipping route, Murotsu’s port district was where the richest and most politically powerful merchant households were located: where most houses boasted the status-symbol of a tiled roof, and where the most successful wholesalers enjoyed privileges normally reserved for the samurai, including surnames and walled gardens.

At the heart of these merchants’ activities was a complex money-making system that depended on both collection and circulation. Suppose, in 1842, that you were the captain and owner of a small cargo ship sailing eastwards through the Inland Sea. Your ship carries up to 1,000 koku (approximately 5,000 bushels) of newly harvested rice from your home domain of Kaga, in north-east Japan – a cargo which you have purchased on the Kaga market for 𝒙 silver monme, and which you therefore want to sell at profit in Osaka. You have arrived in the Kaminoseki straits after a long day’s sail from Shimonoseki,Footnote 45 and you anchor at Murotsu to stock up on fresh water. When a rowboat from one of the port’s teahouses draws up alongside your ship, some of your six-strong crew hop in, planning to spend a night carousing with the establishment’s young women (and occasional young men).

But the next morning, the strong westerlies which hastened the previous day’s passage from Shimonoseki have turned into an easterly breeze. With such a headwind, it will be impossible to tack against the tidal currents rushing through the straits. So you summon one of the many rowboats milling around in the port – here and in Kaminoseki, there are more than 100 cargo ships at overnight anchor, to which the rowboats hawk their business – and go ashore to pay a courtesy call to one of Murotsu’s most important merchant dynasties, the Yoshida household. (Unlike you, they carry a surname.) As you step off the sturdy stone dock, you fall into conversation with a fellow captain waiting for a rowboat back to his ship. He is making haste for departure, wanting to use the easterly to sail towards Shimonoseki. He was in Osaka ten days ago, he says, and the price of rice was dropping like a stone in an empty well. Perhaps it will have recovered by the time you arrive in approximately a week – depending on the winds – but perhaps it will continue to fall. If it drops anything below 𝒙 monme, you’ll be carrying a loss-making cargo and have no capital to buy the tea and sugar you intended to ship back for sale in Kaga.

So when you enter the Yoshida grounds – there is a roofed gate in the wall that surrounds the property – you have a deal on your mind. Crossing the Yoshida’s small but immaculate garden, you pass a two-storey warehouse where servants are stacking small barrels of sake and soy sauce. In the reception room of the household’s large main building, you are greeted by eighth-generation household head Yoshida Bunnoshin, and you begin a formal negotiation.Footnote 46 He offers to store your potentially loss-making cargo and sell it on commission; you prefer him to buy the rice outright. He haggles down the price before agreeing, and he summons more servants to prepare the unloading of your ship. In the meantime, he suggests you partake of lunch together – bream, rice, wakame soup, pickled plums all the way from the Kii peninsula. Sated, you drop into a bathhouse on the way back to the waterfront for a scrub and a soak. You will be up early tomorrow to buy an alternative cargo for transportation to the Osaka markets (Yoshida has made a couple of suggestions, based on intelligence passing through the port); but perhaps tonight you might also visit a teahouse.

Fundamentally, the port economy reconstructed here depended on circulation: of goods, information, money, and naturally the ships that channelled these things. Contrary to a popular stereotype of staid village life, Murotsu and other Inland Sea ports were worlds constantly in flux. But such circulation would have been impossible without the constant heartbeat of labour. The captain’s transactions alone depended on the manual labour (in order of previous appearance) of the water carriers, the rowboat oarsmen, the teahouse women, the stevedores, the servants, the fishermen, the cooks, the bathhouse maids and the wood cutters – and this was for just one of hundreds of daily interactions between port residents and visiting ships. To borrow the lexicon of Utagawa Kunisada, such workers were the fanners, the stokers, the shovellers and the millers through which circulation was enabled; to borrow the lexicon of the 2010s and 2020s, they were the labourers in a gig economy.

But these men and women did not – could not – live among the established denizens of the port district itself. Instead, many of them lived in what Chōshū administrators termed the ‘inland district’ (jikata 地方), which included both the port’s hillside suburbs and also farming hamlets located several kilometres up the Murotsu peninsula. These were poorer communities, where the cost of living was cheaper. In terms of reported income in 1842, that of the inland district constituted only a third of the port’s, while the houses here were smaller and only had thatched roofs. Yet between the 1730s and the 1840s, the number of households in this district almost quadrupled, to 232. Most significantly, 88 per cent of these households owned no land – an even higher percentage than in Wakamiya’s home village of Jigozen (see Chapter 2).

Such a demographic transformation in Murotsu’s poorer, inland districts only makes sense if we assume that the port acted as an economic magnet for the region as a whole. That is, the quadrupling of inland district households, which outstripped the accompanying population increase in the same period,Footnote 47 suggests that there was considerable inward migration from the mid eighteenth to the mid nineteenth centuries. If you felt moved to establish a new household in Murotsu’s inland district during this period, you were unlikely to be acting on the prospect of empty farm land waiting to be exploited. Instead, you were probably planning to engage in subsistence farming and otherwise earn cash by working in the port – as a carrier or oarsman or stevedore.Footnote 48 And if you didn’t own land, then so be it: your port-based by-employment would hopefully offer your household enough security.

This was something like the world into which Fuyuki Sakazō was born, in approximately 1868. Although the Fuyuki address later listed in the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs paperwork is impossible to trace to an exact street, his inland district household would have lain in walking distance of the port district. Most likely, the port’s prosperity would therefore have generated by-employments for the household’s previous generations – even if, on paper, Fuyuki’s ancestors were classified as ‘farmers’ (nōnin 農人).Footnote 49

But by Fuyuki’s teenage years, the types of circulations on which the port economy depended had been profoundly disrupted: first by Japan’s reengagement with international trade in the late 1850s; then by the transformations to domestic trade which accompanied the Meiji revolution and the subsequent abolition of the domains;Footnote 50 and, perhaps most importantly, by the gradual introduction, after 1872, of the telegraph to Japan. This is because the instantaneous communication of price information across the national realm rendered obsolete the system of regional price betting on which merchant households such as the Yoshida made their money. The shippers might still come to port – although with the eventual introduction of steam technology to the Inland Sea routes, even this was no longer a given, as winds and tides would no longer delay speed-conscious captains. But if there were no longer demand either for transactions involving unknown price differentials or for the storage of commodities in transit, then there were consequently fewer profits for the merchants to make. Such were the factors behind a petition which several Murotsu merchants addressed to the village mayor in 1894:

The fact is, despite us being called the most prosperous port in the [western Japan] region, world conditions have been transformed: the domains have been replaced by the prefectural system; the coming and going of official ships has stopped; most shipping has become steam-powered; goods are being transported directly to meet demand; and both commercial shipping and merchants are no longer coming.Footnote 51

The reduced circulation of ships, goods and capital had thus severely affected the port district by the early 1890s, half a century after Chōshū officials enumerated all the hallmarks of a booming economy.

But the structures of Murotsu’s mid nineteenth-century economy dictated that the impact of such transformed world conditions actually fell first – and hardest – on the poorer inland communities, for fewer profits in the ports translated into fewer by-employments for inland residents. Even back in 1842, domain administrators had been concerned by the demographic fragility of the Murotsu inland district, describing rice production as insufficient for people’s needs, and dry fields cultivated to the crests of the ridges and the depths of the valleys. In other words, overpopulation and cramped land were socioeconomic realities even before there existed a Malthusian rhetoric which officialdom could deploy to conceptualize the problem.Footnote 52

Although the circumstances of port decline were particular to Murotsu, here as elsewhere in late nineteenth-century Yamaguchi, new domestic industries offered an outlet for the newly impoverished to find employment. Young women could go to the silk mills in places such as Tomioka, far to the east; young men and women could go work in the coal mines of Fukuoka prefecture in Kyushu (see Chapter 6).Footnote 53 But by the late 1880s, overseas migration in particular offered a potential panacea to the troubles of the inland district’s nominal farmers. ‘Murotsu is by far the most impoverished village’, a village official wrote to his county counterpart in November 1888. Most probably with the inland district in mind, he explained: ‘There is [high] population relative to the amount of land, such that our economy could not survive without out-migration labour; we are in great hardship.’Footnote 54 Already the village had received approximately 150 applications to the new government-sponsored emigration programme, but to date, no one from Murotsu had actually crossed to Hawai‘i. The implication was clear: Murotsu, as also Kaminoseki and other villages in Kumage county, had been unfairly treated in comparison to neighbouring Ōshima, whence hundreds of Hawaiian migrants had departed since the programme’s first crossings in 1885.

Whether by coincidence or as a direct consequence of the official’s appeal, thirty-eight Murotsu villagers were accepted onto the emigration programme’s seventh crossing, in December 1888. Among their number was Fuyuki’s first cousin, Kōchiyama Kanenoshin (also born c. 1868), who, according to Fuyuki’s granddaughter, must have written home early in 1889 – or had someone write for him – to encourage other villagers to emigrate.Footnote 55 These were the kinds of circulatory information networks which Irwin had in mind when he wrote to Lorrin Thurston in October 1889, the month that Fuyuki and fifty-two more Murotsu villagers arrived in the kingdom:

‘[t]he Japanese immigrants now in Hawaii have sent highly favorable reports to their families and friends, and the Emigration is very popular in Yamaguchi and Hiroshima […] I personally sent my Secretary, Mr. Onaka, to every district in Yamaguchi and Hiroshima, which he visited between September 21st and October 11th.Footnote 56

If ever a name was apt for a pun, this is it: in addition to being a surname, onaka – with different characters – is a generic term for ‘stomach’ in Japanese. Thus, in the style of Utagawa’s ‘Rules of Dietary Life’, Mr Stomach shovels young Murotsu men on their way to the mills and fields of Hawai‘i. And yet the body metaphors are transmuted in this reading: whereas at the beginning of the 1850s the Fuyuki household and its neighbours had been the figurative fanners and beaters in the circulatory port economy, by the end of the 1880s they had themselves become the objects of circulation, herded and carried and beaten – literally, by some luna – as crucial raw materials of the sugar plantation economy.

This, then, was the world of the holehole bushi lyrics: ‘The cane drifts down to the flume / To the mill. / As for my body – / where will it drift?’ And, in the very different context of international diplomacy, it was also the world depicted by the official diarist of the Iwakura Mission to North America and Europe (1871–3). Reflecting in one entry on the nature of international trade, he described London, Marseilles, Amsterdam, Hamburg and many European ports ‘whose names are heard less frequently’ in terms of ‘how the world’s products circulate [ryūtsū 流通]’:

[Raw materials] are carried along the sea-lanes and unloaded at the main ports. They make their way overland to the factories of every region, and the [subsequent] manufactured goods are then sent from the main inland hubs back to the ports [gyakuryū 逆流]. This is like the flow [ryūnyū 流入] of a hundred rivers or the pulsing of blood through the arteries. And, like the ebb of the tide or the flow of blood back along the veins, the goods in the ports flow back [tōryū 倒流] to every region [of the world].Footnote 57

The character ryū 流 is also read nagareru: it is the same character used by late-Tokugawa intellectuals in their explanations of economic principles, and the same verb used to conjure up flowing bodies in the plantation song.

We need not assume that the Japanese labourers toiling in Hawai‘i had read Tokugawa tracts, perused the Iwakura Mission’s diaries, or even seen Utagawa’s popular woodblock print when they lifted a terminology so laden with theoretical baggage for their songs. Indeed, it’s unlikely that a Murotsu migrant would have narrated the port’s history with the language I have just used, even if my story’s general flow would have been recognizable. And yet at some level it seems justified to assume that the language of ‘drifting’ was not entirely devoid of historical meaning and memories in the holehole bushi. Indeed, by-employments in the particular context of Murotsu may have strengthened a worldview in which the natural order of things was characterized by circulation. In turn, this may have facilitated the labourers’ understanding of their own mutation into commodified bodies which circulated – which, in the words of the holehole bushi, drifted down to the mill. And if that mill happened to be in Hawai‘i and not Japan, and if it happened to refine cane rather than weave cotton or silk, then the industrial project for which Murotsu-based by-employments might be said to have ‘prepared’ migrant labourers was the Maui sugar factory or plantation field. To return to Thomas C. Smith, by-employments indeed constituted a ‘connection’ from an agricultural to an industrial history – but one that traversed the Pacific. By this logic, the holehole bushi are as much an archival departure point for what Smith called ‘speculations’ about the nature of nineteenth-century Japanese economic transformations as the surveys compiled by Chōshū officials in Kaminoseki.

Outside (2): Kaminoseki Municipal Archives

If songs from the Hawaiian canefields offered a different historical inflection on statistics from Kaminoseki, then the next step in exploring the nature of transpacific ‘circulations’ was to see if the reverse were true – namely, if and how sources from rural Japan might offer a new lens through which to consider transformations in late nineteenth-century Hawai‘i. For this, the archival departure point was the Kaminoseki Board of Education, with its view over the straits to Murotsu port and beyond to the regal slopes of Mount Ōza (527m), literally the ‘emperor’s seat’ (皇座). Here, local legend claims that during the epochal late twelfth-century struggle between the rival Minamoto and Heike clans, the boy emperor Antoku (1178–85) scanned the Inland Sea for the white sails of the despised Minamoto ships – in contrast to his own Heike red.Footnote 58

The Board of Education, on what the Japanese called the second floor of a nondescript concrete building also housing the Chamber of Commerce, was the closest that Kaminoseki had to a municipal archive, to a repository of records documenting the individual villages and islands – Murotsu, Yashima, Iwaishima, Kaminoseki itself – which had administered the everyday lives of local people until the town merger in 1958. The narrow office that the head of education kindly offered me was the equivalent to an archival reading room. By contrast, the ‘stacks’ were downstairs, left out of the main entrance, a hop down the town’s seafront road, another left into a sheltered alley, and then a right into a large wooden warehouse – which in 2007 had seen better days and within a few years would be demolished entirely.

I had first been brought here in the spring of 2007 by the Board of Education’s Kawamura Mitsuo, an archival gatekeeper whose enthusiasm for The History of Japan was unrivalled if somewhat dilatory. Then a stocky man in his late fifties, with tousled greying hair and uneven outgrowths of stubble, the late Mr Kawamura’s greatest passion was the stone wall architecture of Iwaishima island, where he’d insisted on taking me for a study-morning. (‘Mi-chan’s tour’, my father-in-law had chuckled, using the affectionate nickname by which Kawamura-san was known to most townspeople.) On the ferry ride back, I broached not for the first time the topic of the warehouse – in the whole town, only Mr Kawamura seemed to have a set of keys – while he regaled me with more tall wall tales. At the end of the day, he pressed further reading material into my hands – this time, a thick official report which until my next bout of insomnia lay unopened at home – and agreed to unlock the warehouse the following Thursday.

What we found that Thursday morning, in an unlit rear room and under the cover of tarpaulin, were some eighty cardboard boxes containing mainly Murotsu village documents from the 1870s to the 1958 merger. This was my first encounter with serious archival dust – and damp, and the occasional louse – and it made me drunk on the possibilities of the handwritten document.Footnote 59 For subsequent months on end, I opened and sniffed through boxes we had decanted from the stacks to the reading room, only occasionally interrupted by Mr Kawamura and his curious colleagues. For reasons I have trouble fathoming some fifteen years later, I used my digital camera only rarely. Instead, unconsciously adhering to an older paradigm of archival research as a period of reading not photographing, I spent my time transcribing texts and entering households into ever more unwieldy Excel spreadsheets. The name of Fuyuki Sakazō did not immediately leap out from the pages, but it recurred enough for me to know that I might one day attempt a short biography – and, in an act of great generosity which also underlined the town’s dense social networks, Mr Kawamura would later put me in touch with one of Fuyuki’s surviving granddaughters in Osaka.

Each unpacked box helped fill out Fuyuki’s story. From the tax records, I could calculate the relative prosperity of Murotsu’s two Fuyuki households in 1891, eighteen months after his departure. From pupil lists, I knew some of his children had been enrolled in the elementary school in the 1910s. From fundraising appeals, I read that he had pledged significant donations towards a new school hall in 1914.Footnote 60 And in the village’s land registers – which I accessed in a neighbouring town – I discovered that in 1913 he had purchased three properties in the port district of Seto, just across the straits from the Board of Education.Footnote 61 This chronology was at first confusing: only after Fuyuki’s granddaughter wrote to me did it become clear that Sakazō returned to Murotsu in the late 1890s to marry his first cousin, Kōchiyama Sumi (quite possibly the younger sister of Kanenoshin, who had preceded Fuyuki to Hawai‘i by a few months in 1889); that the first of their eight children was born in Hawai‘i in 1901; that the last two children were born in Japan in the 1910s, after Sumi emigrated back to Murotsu; that most of the children attended school in Japan; and that Sakazō himself also spent some time in Murotsu in the 1910s – coinciding with his purchase of new property – before returning to Kaua‘i. His was also a life of flow along the post-1880s artery which connected Yamaguchi to the Hawaiian archipelago.

At the most basic level, the school donations and property acquisitions were all individual markers of how the early twentieth-century material culture of Fuyuki’s home town had been transformed by the Japanese diaspora community: they were indications that ‘the global’ was walked even in the everyday lives of people who stayed at home.Footnote 62 Indeed, the volume of paperwork on my reading room desk testified to the extent that village officialdom needed to think and write in newly expansive ways by the 1910s compared to just forty years earlier, as harried record keepers tried – and, in the case of mistakenly placing Fuyuki in Kapa‘a, often failed – to keep accurate track of who was residing where in the Asia-Pacific world. In the Foreign Ministry archives in Tokyo, the story was the same, but on a bigger scale. In addition to enumerating comings and goings, for example, ministry officials gathered reports in 1891 from emigrant-sending prefectures on the post-return employment of the City of Tokio and Yamashiro-maru labourers (although many, such as Wakamiya Yaichi and Kodama Keijirō, did not return after a single contract). Of particular interest was how the migrants had spent the 25 per cent of their Hawaiian wages which they had been obliged to save while working in the canefields. As Fuyuki would later do, many migrants reportedly bought land or property with this money, which officials in Yamaguchi and Kumamoto respectively labelled kinben chochiku 勤勉貯蓄 and kinbenkin 勤勉金 – that is, ‘industrious savings’ and ‘industrious remittances’, themselves the consequence of ‘industrious work’ (kinben rōdō 勤勉労働).Footnote 63

This language of industrious Japanese was equally echoed in Hawaiian government documents. In the same year of 1891, a Bureau of Immigration official wrote to the minister of interior that local authorities in Japan only allowed the overseas migration of ‘men of good character, and those who are law abiding and industrious’.Footnote 64 Back before the government-sponsored programme was even established, the bureau’s president had anticipated that Japanese labourers would constitute ‘an industrious and law-abiding addition to the [Hawaiian] nation’.Footnote 65 Irwin himself, in his letter from onboard the Yamashiro-maru while in quarantine in June 1885 (see Chapter 1), had praised the Japanese as ‘hard working, industrious men’, while the Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser claimed a few months earlier: ‘These people are intelligent, self-respecting, faithful to engagements, and very industrious. Many bring their wives and children with them, transferring to these islands the home life of rural Japan.’Footnote 66

The apparent linguistic alignment of kinben and ‘industrious’ in sources spanning the Pacific Ocean was fortuitous: like Irwin’s labelling of the government-sponsored emigration programme as ‘industrial’, it offered an overlooked Hawaiian entry point into another key historiographical debate concerning Japan’s nineteenth-century transformations, namely the ‘industrious revolution’ (kinben kakumei 勤勉革命). This was a term coined in the 1970s by the economic historian Akira Hayami (1929–2019). In his analyses of demographic data from central Japan, Hayami argued that a supply-side labour transformation had occurred in eighteenth-century Japan, in which the rural population had increased, the amount of capital investment (as measured in farm livestock) had declined – and yet the standard of living, far from falling, had actually risen. He explained this apparent conundrum by emphasizing an intensification of rural labour practices in the period from the 1670s to the 1820s, such that ‘human power replaced livestock power’; and it was this labour-intensive model of structural change he characterized as an ‘industrious revolution’.Footnote 67

In ways that Hayami could hardly have anticipated back in the 1970s, the ‘industrious revolution’ continues to be debated to this day, both within Japan and especially without.Footnote 68 The phrase was adopted and adapted by European historians in the 1990s to describe a slightly different phenomenon in eighteenth-century European history, whereby rural household labour intensified in order both to meet consumer demand (that is, in response to the market) and also to facilitate agricultural households themselves participating in the consumer revolution.Footnote 69 More recently, historians have attempted to sketch a global typology of industriousness – in which they cite Thomas C. Smith’s work on the Murotsu peninsula, itself quoting official descriptions of by-employments from the 1840s, in order to demonstrate the nature of household labour division in rural Japan.Footnote 70 Meanwhile, the aforementioned Shigehisa Kuriyama has argued that the dozens of toiling workers in Utagawa’s ‘Rules of Dietary Life’ comprise a mid nineteenth-century visualization of the labour-intensive industrious revolution.Footnote 71

And so the expectant language of government officials and newspapermen in mid-1880s Hawai‘i seemed to promise an additional reading of the industrious revolution – one in which, in allegedly ‘transferring to these [Hawaiian] islands the home life of rural Japan’, the government-sponsored programme facilitated the circulation of industrious labour from Japan to Hawai‘i and industrious remittances back.

Except, there were two problems with this reading. First, it was not evident that labour-intensive Japanese modes of working did ‘transfer’ to Hawai‘i. Behind some of the worker-management disputes I mentioned in the previous chapter, for example, lay a different conception of working time. As early as July 1885, the Yamaguchi-based Bōchō shinbun newspaper reported on the first group having to learn to keep an eye on the clock at their work stations.Footnote 72 This was partly to protect the labourers from unscrupulous luna – the type who hurried their charges on between tasks, not counting walking time as work time, and who, when faced with recalcitrance, prosecuted the Japanese and testified to the court: ‘I told [the defendants] that they must hurry up as I did not want them to take half a day in going from one field to another and if they did not hurry up I should dock them [pay] and also report them to the Boss.’Footnote 73 Yet overzealous overseers aside, the Yamaguchi newspaper equally noted that the working day in rural Japan, with its frequent breaks for tea or tobacco or lunch, was very different to the plantation expectations in Hawai‘i. Consequently, it had taken the City of Tokio labourers ‘some effort to comply, and the working hours felt very long’.

The idiom of effort – hone o oru, literally ‘to break one’s bones’ – was the same as that used by the exhausted fan-bearers in Utagawa’s ‘Rules of Dietary Life’. It appeared elsewhere – for example, in the instructions issued to the third group of government-sponsored labourers in 1887 (‘Article 1: The attitude of working with great effort required of the migrant workers’), and in the explanation that plantation labour followed set working times without breaks.Footnote 74 In other words, if Utagawa’s conscientious workers were indeed visualizations of the industrious revolution, then the repeated exhortation in official documentation for the Hawai‘i-bound migrants to expend ‘great effort’ implies that Japanese working practices did not transfer well to a canefield setting.Footnote 75 In Hawai‘i, too, the inspector general of immigration publicly suggested in 1886 that:

Great allowances should be made for [the Japanese] at first, as their manner of work (though industrious people) is quite different in their own country, from what it is here; as I am informed, that in Japan, they work a short while and rest, then proceed with their work, so on through the day, whereas, here, they have to work continuously the day through. In a short time, they will be familiar with our mode of work.Footnote 76

All of which suggested a second problem: the ‘industriousness’ for which the Japanese were repeatedly praised in Hawai‘i was not the linguistic equivalent of the labour-intensive modes of work implied in Hayami’s ‘industrious revolution’. Red in one setting was not commensurate with the same idea of colour elsewhere.Footnote 77 Rather, the term ‘industrious’ in Hawai‘i was laden with an ideological baggage of colonial power and the dispossession of Indigenous land – as we shall shortly see. For men like Fuyuki to be praised as ‘industrious’, and for him to contribute to the material culture of his home town by engaging in ‘industrious remittances’, was for him to carry this imposed baggage, too.

In this light, the view across the straits from the Kaminoseki Board of Education to the Murotsu district of Seto, where Fuyuki purchased three properties in 1913, raised new questions. Thanks to the land registers, I knew from whom he had bought the land, but the real point was how he had been in a position to do so.Footnote 78 At whose expense were his ‘industrious’ remittances earned? And thus, just as workers like Fuyuki had been rendered voiceless by the nature of fact assembly in the Hawai‘i State Archives, whose histories had been written out of the Kaminoseki town archives?

‘Invaded by the Industrious’

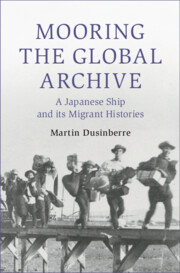

Arriving in Honolulu on the Yamashiro-maru on 1 October 1889, Fuyuki Sakazō was deployed to the Hāna plantation, in eastern Maui, where his bango was 8051 (see Figure 3.2). In November 1897 he boarded the SS Belgic and returned to Japan, eventually to marry his cousin Sumi.Footnote 79 After Hawai‘i was annexed by the United States in 1898, incoming passenger records also noted the traveller’s physical appearance: thus, in his transpacific circulations over the next twenty years, Fuyuki was described as being between four foot ten inches and five feet tall, with a dark complexion and black hair even into his fifties. He had a scar on the index finger of his left hand and a mole on his forehead.Footnote 80

Figure 3.2 Hāna plantation, Maui, c. 1885.

A few months before Fuyuki completed his contract in Hāna, the Paradise of the Pacific newspaper ran an article noting that ‘[t]he district of Hana is one of the least known to the general public of any of the districts on the islands’. One day, the correspondent predicted, it will ‘awake out of sleep’, just like the districts of Kona and Puna on Hawai‘i Island itself – the former ‘now full of the busy hum of industry’, the latter also ‘no longer the dreary, uninhabited waste it used to be’. The article went on to describe the landscape north-west of the Hāna plantation in lyrical terms:

The country is broken by deep gulches, the sides of which run anywhere from 400 to 900 feet, while the plateauxs [sic] between rise to 1200 feet above the sea-level. […] The scenery is magnificent – the finest, by far, on the islands. Roaring cascades dash down steep terraces, finally forming deep streams that waste their waters in the sea. The forests are thick and tangled; wild bananas, ohias and various native fruits grow in luxuriance.Footnote 81

And then the author’s most troubling claim: ‘at present, the whole stretch of territory is practically unused. Some of these days the district will be invaded by the industrious, and the scene will be changed.’

As we have seen, the adjective ‘industrious’ was widely used in late nineteenth-century Hawai‘i as a marker of positive attributes. In the 1880s and 1890s, Japanese labourers were one sub-section of the archipelago’s population – or anticipated population – especially identified in this way, although such labelling was not reserved exclusively for the Japanese, nor was it unambiguously positive.Footnote 82 But behind these allegedly positive connotations lay also a negative evaluation. For the argument that Hawai‘i was ripe for the ‘invasion’ of industrious labourers also constituted an implicit critique of the Native Hawaiian population that itself stretched back to the earliest days of the New England Congregationalist mission in the 1820s. Indeed, the imagination of Hawai‘i as a land calling to be ‘possessed’ and covered with ‘fruitful fields and pleasant dwellings’ – thereby to raise ‘the whole people to an elevated state of Christian civilization’ – even predated the departure of the first American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) expedition for the islands in October 1819.Footnote 83 As Noelani Arista has shown, such tropes were part of the rhetorical production of Hawai‘i and of Hawaiian subjects for a US-American audience. The handful of already converted Hawaiian boys in New England were presented in pamphlets and sermons as ‘industrious, faithful, and persevering’, in contrast to the ‘heathen’ masses whose Christian salvation would be the mission’s raison d’être.Footnote 84 Post-arrival ABCFM missionaries continued to compare their influence on ‘Owhyhee’ to ‘a perennial stream whose gentle flow shall fertilize the barren waste’.Footnote 85

The Paradise of the Pacific’s 1897 article on Hāna demonstrates that these rhetorical productions were still blooming at the end of the nineteenth century – as seen in the description of ‘practically unused’ territory, and in the casual suggestion that the streams ‘waste their waters in the sea’. But the intellectual roots of such claims were not merely missionary. Claus Spreckels, whose Spreckelsville plantation had only been made possible through the diversion of mountain ‘waste’ water to the previously dry plains of north-central Maui, similarly characterized ‘these islands’ as ‘very rich lands’ where there nevertheless remained ‘a great deal’ of wasteland.Footnote 86 Given Spreckels’s animosity towards the many planters who were descended from the ABCFM missionaries and who had agitated for the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, his imagination of Hawaiian ‘waste’ may have drawn less consciously on missionary rhetoric than on a John Locke-inspired justification for colonial acquisition that had animated America’s westward expansion – and which had made Spreckels’s prior business successes in San Francisco possible. It was Locke, after all, who had favourably compared a well-cultivated farm in Devonshire with ‘the wild woods and uncultivated wast [sic] of America’; it was Locke who had argued that ‘common and uncultivated’ land should be given over to ‘the Industrious and the Rational’, and who – in an intellectual justification for English colonial acquisition – suggested that ‘subduing or cultivating the Earth, and having Dominion’, were two sides of the same coin.Footnote 87

In other words, the adjective ‘industrious’ was imbued with deep historical meaning in Hawai‘i by the time it came to be used as a descriptor for the Japanese in the mid 1880s: it connoted both the archipelago’s missionary settlement and the wider colonial expansion of Europe into the New World. We can only speculate as to what it may have meant in the hands of particular authors. The president of the Board of Immigration in 1884, for example, was Charles T. Gulick (1841–97), scion of a missionary dynasty in Hawai‘i. When he wrote that Japanese labourers would constitute ‘an industrious and law-abiding addition to the [Hawaiian] nation’, he may have been drawing on an ABCFM trope from the 1820s; he may also have been influenced by reports from his cousins, Orramel Hinckley Gulick (1830–1923) and John Thomas Gulick (1832–1923), then leading the ABCFM mission in Kobe and Osaka respectively.Footnote 88 Either way, to imagine the Japanese as ‘industrious’ was not merely to express hopes for the government-sponsored migration programme; it was also to bind the new arrivals into a discourse which for decades had presented Hawai‘i as a wasteland, unused, ripe for colonial development – and Native Hawaiians as heathen, indolent and worthy of invasion.Footnote 89

This is important because Fuyuki was no mere bystander in a story of ‘invasion’. For a start, he was a labourer in Hāna during a period of profound change: under the new management of the California-registered Grinbaum & Co. since September 1887,Footnote 90 the number of plantation workers was in the process of more than doubling, from 175 to 454, by the time that Fuyuki had completed his second year of work. At the beginning of 1890, almost two-thirds of the labour force was Japanese, up from just a tenth only two years earlier. During this time, the proportion of Native Hawaiian employees declined from 46 to 12 per cent – almost halving, in absolute terms, to forty-five labourers. By raw numbers, the plantation was expanding at a pace faster than any other on Maui during the same period; by raw numbers, the arrival of government-sponsored Japanese workers – not only in Hāna, but in the kingdom in general – could conceivably be described as an ‘invasion’.Footnote 91

True, Fuyuki was not himself an instigator of what the Paradise of the Pacific might have called ‘scene-changes’ – at least in 1889. But in February 1897, his name appeared in a Murotsu village document, one unusual not for the fact of its existence in the late nineteenth century but rather for its survival. The document is the village mayor’s approval of an application by Hiraki Yasushirō, born in March 1859 and therefore a month shy of his thirty-eighth birthday, for independent passage to Hawai‘i. There are the standard brief explanations of Hiraki’s financial situation, his upright conduct, the parental approval he has received – many years after he first wanted to go to Hawai‘i – and his lack of conscription obligations. I can work out that his household was located in Yamaga, a short walk up from Murotsu port and therefore an ‘inland district’ suburb in the 1840s; the application states that he was a farmer. But the passage that leaps out of the page concerns Hiraki’s work intentions:

His younger cousin [Fuyuki] Sakazō is currently employed in the sugar industry on the Hāna Plantation in Maui, Kingdom [sic] of Hawai‘i, by the American Mōrison. Due to the latter [Mōrison] preparing labour contracts and summoning [labourers] at this time, [the applicant] will cross to Hawai‘i with the purpose of engaging in labour on the sugar plantations.Footnote 92

In other words, Fuyuki has passed on information to his cousin, Hiraki Yasushirō, about new employment opportunities in Maui – just as he, too, had been spurred by reports from his cousin Kōchiyama Kanenoshin to apply for the emigration programme back in 1889.Footnote 93 There was no government-sponsored programme after 1894, a casualty both of Hawai‘i’s post-overthrow government trying to reduce the financial obligations on the planters and of the Japanese government’s requisitioning of NYK ships for the Sino-Japanese War (see Chapter 4);Footnote 94 but otherwise, the transpacific flow of information was similar in both cases.

All of which suggests two plausible interpretations. The first is that historians can understand Fuyuki’s role in his cousin’s 1897 recruitment through the holehole bushi-inspired analytical framework of circulation. Here was a classic example of information being shared on the metaphorical portside docks, of the constant shovelling of labour from Japan to Hawai‘i benefiting respective supply- and demand-side needs. Here was a labourer in Hawai‘i choosing not to leave the flow of bodies down to the mill to chance, but rather trying to direct them to the benefit of his extended family and his home town – and, in the process, facilitating a transition from ‘agricultural’ to ‘industrial’ modes of work which traversed the Pacific Ocean. Here was a man, himself shortly to return to Japan after two contracts at Hāna, refusing to end up as fertilizer in the canefields.

The second plausible interpretation, not incompatible with the first but requiring a slightly longer explanation, is that the Murotsu paperwork constitutes a document of plunder – to paraphrase Prendergast’s ‘Kaulana Nā Pua’ song – and that, as such, Fuyuki’s history can also be understood through the analytical framework of settler colonialism. This is because, as scholars have recently argued, the history of colonialism in the Hawaiian archipelago was not simply a binary story of white settler dispossessing Native Hawaiian – be that through the labelling of Indigenous people as allegedly indolent and immoral, or through the dismissal of the land as ‘unused’ and therefore worthy of exploitation through the legal framework of ‘property’.Footnote 95 Rather, Asian migrant labourers, chief among them the Japanese, also ultimately benefited from the colonial structures of property, education and eventual Hawaiian statehood. In its most provocative articulation, by the aforementioned Haunani-Kay Trask, this argument critiques the archetypal immigrant ‘success’ story, from first-generation plantation hardship to later-generation political or entrepreneurial ascendancy, as ‘made possible by the continued national oppression of Hawaiians, particularly the theft of our lands and the crushing of our independence’.Footnote 96

One problem with such arguments is that they tend to be ex post facto: that is, subsequent successes and settlement in mid twentieth-century Hawai‘i in and of themselves rendered the original migrant labourer a ‘colonist’, even if he – almost always a male protagonist – at first harboured intentions merely to serve his contract and remit what he could to his household in Japan.Footnote 97 This is why the February 1897 application in Murotsu is so unusual and revealing, for it shows Fuyuki Sakazō actively recruiting new labourers on behalf of ‘the American Mōrison’. Indeed, when I use keyword searches to contextualize the 1897 document a little further, Fuyuki’s potential ‘complicity’ (Trask’s word) in a story of Native Hawaiian dispossession is rendered more visible. ‘The American Mōrison’ was not, in fact, American: Hugh Morrison was born in 1844 in Aberdeen and, as he told a newspaper interviewer in January 1896, a proud ‘Scotch’.Footnote 98 Nor was he ever an employer at Hāna: having come to Hawai‘i in 1879 and initially worked at the Hakalau plantation, he served as the manager of Spreckelsville from 1887 to 1891 and then, until his death in 1901, as the manager of the new Hawaiian Sugar Company plantation at Makaweli, Kaua‘i.Footnote 99 Given the distance between Maui and Kaua‘i, Fuyuki is unlikely to have been personally acquainted with Morrison; but he probably knew of him through his own manager on Hāna until 1897, David Center, another Scot, whose brother was also Morrison’s brother-in-law.Footnote 100 Thus, in passing news of Morrison’s recruitment drive on to his cousin Hiraki in Murotsu, Fuyuki was advancing the interests of a group of managers whose networks encompassed both Hāna in Maui and Makaweli in Kaua‘i. (Given that Fuyuki himself eventually ended up living in the neighbouring Kaua‘i town of Eleele, he may also have been setting up a relationship from which he would later benefit.)Footnote 101

In the aforementioned newspaper interview, Morrison was asked by the American journalist Kate Field (1838–96) to speak to the ‘political principles’ of the planter class. ‘We are determined that there shall be no more monarchy,’ he answered. ‘A large majority of us want a settled government. We need it for our peace of mind as well as for our pockets.’ Contrasting the alleged ‘orgies’ of the late King Kalākaua’s rule to the ‘admirable’ men running the post-overthrow Republic of Hawai‘i, Morrison looked to the future: ‘Though a British subject, I realize, as every one must, that these islands are to all intents and purposes American. They owe their prosperity to the United States, and we are ready for annexation.’Footnote 102

Recall now the image of the ‘evil-hearted’ in Prendergast’s ‘Kaulana Nā Pua’, and the lament – from the third stanza – that ‘Annexation is wicked sale / Of the civil rights of the Hawaiian people’. If Morrison fitted this stereotype of the Native Hawaiians’ foe in the mid 1890s, then Fuyuki’s furthering of managerial interests through the recruitment of his cousin in Japan would seem ultimately to have assisted both the annexation agenda and future prosperity of the planters’ pockets. Unlikely though it may seem, this five-foot man with a scar on his index finger and a mole on his forehead was also an invader of sorts.

Interpreting