In 2012, Facebook’s Data Science team decided to conduct an experiment to see whether and how they could affect the emotions of the platform’s users.Footnote 1 For a week, they altered the feeds of 689,003 Facebook users. Some of the users were exposed to fewer posts with positive words or phrases; some of the users saw fewer posts with negative words or phrases. The question was simple: Would this intervention change the kinds of emotions that Facebook users displayed online? In other words, would the platform see emotional contagion?

The answer was clear. Facebook did indeed have power over the emotions of its users. People who were exposed to fewer negative posts ended up making fewer negative posts. People who were exposed to fewer positive posts made fewer positive posts. As the authors put it, “emotions expressed by others on Facebook influence our own emotions, constituting experimental evidence for massive-scale contagion via social networks.”

The experiment produced widespread alarm, because people immediately saw the implication: If a social media platform wanted to manipulate the feelings of its users, it could do exactly that. A platform could probably make people feel sadder or angrier, or instead happier or more forgiving.

***

It ranks among the most powerful scenes in the history of television. Don Draper, the charismatic star of Mad Men, is charged with producing an advertising campaign for Kodak, which has just invented a new slide projector, with continuous viewing. It operates like a wheel. Using the device to display scenes from a once-happy family (as it happens, his own, which is now broken), Draper tells his potential clients:Footnote 2

In Greek, “nostalgia” literally means, “the pain from an old wound.” It’s a twinge in your heart, far more powerful than memory alone. This device isn’t a spaceship. It’s a time machine. It goes backwards, forwards. It takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called the Wheel. It’s called the Carousel. It lets us travel the way a child travels. Around and around, and back home again … to a place where we know we are loved.Footnote 3

The Kodak clients are sold. They cancel their meetings with other companies.

***

In 2018, Cambridge Analytica obtained the personal data of about 87 million Facebook users. It did so by using its app called, “This Is Your Digital Life.” The app asked users a set of questions designed to learn something about their personalities. By using the app, people unwittingly gave Cambridge Analytica not only answers to those questions but also permission to obtain access to millions of independent data points, based on their use of the Internet. In other words, those who answered the relevant questions were taken to have “agreed” to allow Cambridge Analytica to track their online behavior. Far more broadly, they gave the company access to a large number of data points involving the online behavior of all of the users’ friends on Facebook.

With these data points, Cambridge Analytica believed that it had the capacity to engage in “psychological targeting.” It used people’s online behavior to develop psychological profiles, and then sought to influence their behavior, their attitudes, and their emotions through psychologically informed interventions.

Through those interventions, Cambridge Analytica thought that it could affect people’s political choices. According to a former employee of the firm, the goal of the effort was to use what was known about people to build “models to exploit what we knew about them and target their inner demons.”Footnote 4 Pause over that, if you would. We could easily imagine a similar effort to affect people’s consumption choices.

***

In 2024, while writing this book, I received an email from “Research Awards.” The email announced that one of my recent publications “has been provisionally selected for the ‘Best Researcher Award.’” It asked me to click on a link to “submit my profile.” It was signed: “Organizing Committee, YST Awards.”

The article, by the way, was on the topic of manipulation. Does the Organizing Committee have a sense of humor?

I did not click on the link.

***

To understand manipulation, we need to know something about human psychology – about how people judge and decide, and about how we depart from perfect rationality. Consider the following cases:

1. A social media platform uses artificial intelligence (AI) to target its users. The AI learns quickly what videos its users are most likely to click on – whether the videos involve tennis, shoes, climate change, immigration, the latest conspiracy theory, the newest laptops, or certain kinds of sex. The platform’s goal is to maximize engagement. Its AI is able to create a personalized feed for each user. Some users, including many teenagers, seem to become addicted.

2. A real estate company presents information so as to encourage potential tenants to focus only on monthly price and not on other aspects of the deal, including the costs of electricity service, water, repairs, and monthly upkeep. The latter costs are very high.

3. A parent tries to convince an adult child to visit him in a remote area in California, saying, “After all, I’m your father, and I raised you for all those years, and it wasn’t always a lot of fun for me – and who knows whether I’m going to live a lot longer?”

4. A hotel near a beach advertises its rooms as costing “just $200 a night!” It does not add that guests must also pay a “resort fee,” a “cleaning fee,” and a “beach fee,” which add up to an additional $90 per night. (There are also taxes.)

5. In an effort to discourage people from smoking, a government requires cigarette packages to contain graphic, frightening health warnings depicting people with life-threatening illnesses.

6. In a campaign advertisement, a political candidate displays ugly photographs of his opponent, set against the background of terrifying music. An announcer reads quotations that, while accurate and not misleading, are taken out of context to make the opponent look at once ridiculous and scary.

7. In an effort to convince consumers to switch to its new, high-cost credit card, a company emphasizes its very low “teaser rate,” by which consumers can enjoy low-cost borrowing for a short period. In its advertisement, it depicts happy, elegant, energized people, displaying their card and their new purchases.

8. To reduce pollution (including greenhouse gas emissions), a city requires public utilities to offer clean energy sources as the default providers, subject to opt-out if customers want to save money.

Which of these are manipulative? And why?

Coercion

To answer these questions, we need to make some distinctions. Let us begin with coercion, understood to involve the threatened or actual application of force. If the law forbids you to buy certain medicines without a prescription, and if you would face penalties if you violate that law, coercion is in play. If the police will get involved if you are not wearing your seatbelt, we are speaking of coercion, not manipulation. If you are told that you will be fined or imprisoned if you do not get automobile insurance, you are being coerced.

Note that it is false to say that when coercion is involved, people “have no alternative but to comply.” People do have alternatives. They can pay a fine, or go to jail, or attempt to flee.

It is often said that government has a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, which means that in a certain sense, coercion is the province of government and law. But we might want to understand coercion a bit more broadly. If your employer tells you that you will be fired if you do not work on Saturdays, we can fairly say that in an important respect, you have been coerced. If a thief says, “your money or your life,” we can fairly say that you have been coerced to give up your money. A reference to “coercion,” in cases of this kind, is unobjectionable so long as we know what we are talking about.

Coercion is usually transparent and blunt. No trickery is involved, and no one is being fooled. Coercion typically depends on transparency.

What is wrong with coercion? That is, of course, a large question. Often coercion is unobjectionable. If you are forbidden from murdering people, or from stealing from them, you have been coerced, but there is no reasonable ground for complaint. People do not have a right to kill or to steal. If you are forbidden to speak freely, or to pray as you think best, we can say that the prohibition offends a fundamental right.

Paternalistic coercion raises its own questions. Suppose that people are forced to buckle their seatbelts, wear motorcycle helmets, or eat healthier foods. Many people object to paternalistic coercion on the ground that choosers know best about what is good for them – about what fits with their preferences, their desires, and their values. Even if they do not know best, they can learn from their own errors. Maybe people have a right to err; maybe they are entitled to be the authors of the narratives of their own lives. These points bear on what manipulation is and why it is wrong; I will return to them.

Lies

Lies may not coerce anyone. “This product will cure baldness” says a marketer, who knows full well that the product will do nothing of the kind. But what is a lie? According to Arnold Isenberg, summarizing many efforts, “A lie is a statement made by one who does not believe it with the intention that someone else shall be led to believe it.”Footnote 5 Isenberg adds: “The essential parts of the lie, according to our definition, are three. (1) A statement – and we may or may not wish to divide this again into two parts, a proposition and an utterance. (2) A disbelief or a lack of belief on the part of the speaker. (3) An intention on the part of the speaker.”

The definition is helpfully specific and narrow. Ordinarily we understand liars to know that what they are saying is false and to be attempting to get others to believe the falsehood. According to a similar account by Thomas Carson, “a lie is a deliberate false statement that the speaker warrants to be true.”Footnote 6

Here is a vivid example from John Rawls, speaking of his experience during World War II:Footnote 7

One day a Lutheran Pastor came up and during his service gave a brief sermon in which he said that God aimed our bullets at the Japanese while God protected us from theirs. I don’t know why this made me so angry, but it certainly did. I upbraided the Pastor (who was a First Lieutenant) for saying what I assumed he knew perfectly well – Lutheran that he was – were simply falsehoods without divine provenance. What reason could he possibly have for his trying to comfort the troops? Christian doctrine should not be used for that, though I knew perfectly well it was.

I think I know why the Pastor’s sermon made Rawls so angry. The Pastor was not treating the troops respectfully. Actually he was treating them with contempt. Even worse, he was using Christian doctrine in bad faith. He was using what he said to be God’s will, but did not believe to be God’s will, in order to make people feel better. That is a form of fraud. It is horrific. It is a desecration.

Inadvertent falsehoods belong in an altogether different category. If you say, “climate change is not real,” and if that is what you think, you are not lying, even if what you say is false. You might be reckless or you might be negligent, but you are not lying.

It is noteworthy that the standard definition of lying does not include false statements from people with various cognitive and emotional problems, who may sincerely believe what they are saying. In the 1960s, my father had a little construction company and he worked near a mental hospital. He was often visited by someone who lived there, who would give my father a large check and say, “Mr. Sunstein, here’s a check for you. I have enough funds to cover it. Will this be enough for the day?”

It is fair to say that while my father’s visitor was not telling the truth, he was not exactly lying. We would not respond to my father’s benefactor with the same anger that Rawls felt toward the Pastor.

Or consider the case of confabulators, defined as people with memory disorders who fill in gaps with falsehoods, not knowing that they are false. Nor does the definition include people who believe what they say because of motivated reasoning. People often believe what they want to believe, even if it is untrue, and people whose beliefs are motivated may not be liars. They might be motivated to say that they are spectacularly successful, and while that might not be true, they might not be lying, because they believe what they say. They might say, “My company is bound to make huge profits in the next year,” not because there is any evidence to support their optimistic prediction, but because they wish the statement to be true. Such people might be spreading falsehoods, but if they do not know that what they are spreading is false, it does not seem right to describe them as “lying.”

Deception

Now turn to deception. It is often said that the term is broader than “lying.” On a standard definition, it refers to intentionally causing other people to hold false beliefs. You might deceive people into holding a false belief without making a false statement. You might sell a new “natural pain medication” to willing buyers, referring truthfully to the testimony of “dozens of satisfied customers,” even though there is no evidence that the pain medication does anyone any good. You might sell an airline ticket to a beautiful location, stating that the ticket costs “just $199,” without mentioning that the ticket comes with an assortment of extra fees, leading to a total cost of $299. You might sell your house to a naïve buyer, emphasizing that it has not been necessary to make any repairs over the last ten years, even though it is clear that the house will need plenty of repairs over the next six months. In all of these cases, you have deceived people without lying.Footnote 8

What is wrong with lying and deception? (For present purposes, we can group them together.) They are often taken to be illicit forms of influence. Return to Rawls’ Pastor, who treated the soldiers disrespectfully. Much of the time, liars and deceivers are thieves. They try to take things from people (their money, their time, their vote, their sympathy) without their consent.

Still, we have to be careful here. It is widely though not universallyFootnote 9 agreed that some lies are acceptable or perhaps even mandatory. A few decades ago, my father started to stumble on the tennis court. My mother and I brought him to the hospital for various tests. After conferring with the doctor, my mother came to my father’s hospital room to announce, “I have great news. They didn’t discover anything serious. They will keep you here for another day, out of an excess of caution, but basically, you’re fine!”

When my mother took me downstairs, to drive me back to law school, her face turned ashen. She said, “Your father has a brain tumor, and there’s nothing they can do about it. He has about a year. But I’m not going to tell him, and you’re not, either.”

Was she wrong to lie to him? I don’t know. Was Bill Clinton wrong to lie to the American people about his relationship with Monica Lewinsky? I believe so, but not everyone agrees.Footnote 10

Consider the following propositions:

1. If an armed thief comes to your door and asks you where you keep your money, you are entitled to lie.

2. If a terrorist captures a spy and asks her to give up official secrets, she is under no obligation to tell the truth.

3. If you tell your children that Santa Claus is coming on the night before Christmas, you have not done anything wrong.

4. If you compliment your spouse on his appearance, even though he is not looking especially good, it would be pretty rigid to say that you have violated some ethical stricture.

We should conclude that lies and deception are generally wrong, and I will have something to say about why. But they are not always wrong.

Meaning and Morality

A great deal of effort has been devoted to the definition of manipulation, almost exclusively within the philosophical literature.Footnote 11 Most of those efforts are both instructive and honorable, and I will build on them here. In the end, it might be doubted that a single definition will exhaust the territory. I will be offering two quite different accounts (one in this chapter and one in Chapter 6), and there are others.

Let us begin with some methodological remarks. On one account, defining manipulation is an altogether different enterprise from explaining why and when manipulation is wrong. We might say that manipulation occurs in certain situations and then make an independent judgment about when or whether it is wrong. We might conclude that it is presumptively wrong, or almost always wrong, because of what it means or does. Or we might think that it is often justified – if, for example, it is necessary to increase public safety or improve public health.

On another account, manipulation is a “thick” or “moralized” concept, in the sense that it always carries with it a normative evaluation. Compare the words “generous,” “brave,” “kind,” and “cruel”; any definition of these words must be accompanied with a positive or negative evaluation. To say that an act is “generous” is to say that it is good. You might think that to say that an act is “manipulative” is to say that it is bad.

In my view, the first account is right, and it is the right way to proceed. A manipulative act might be good. You might manipulate your spouse in order to reduce serious health risks that she faces. A doctor might manipulate a patient for the same reason. True, you might say, in such cases, that manipulation is pro tanto wrong, or presumptively wrong, and that like coercion, deception, or lying, a pro tanto wrong or a presumptive wrong might ultimately be right (and perhaps morally mandatory). But we can, I think, define manipulation before offering a judgment about when and whether it is right or wrong. In any case, that is the strategy that I will be pursuing here. And my own preferred definitions in this chapter, intended not to be exhaustive but to capture a set of important cases of manipulation, will turn out to embed something like an account of why manipulation is presumptively wrong.

The task of definition presents other puzzles. When we insist that “deception” means this, and that “manipulation” means that, what exactly are we saying? Are we trying to capture people’s intuitions? Are we trying to capture ordinary usage? What if intuitions or usages diverge? Are we seeking to capture the views of the majority? If so, are we asking an empirical question, to be resolved through empirical methods? What would those methods look like? Can artificial intelligence help? More broadly: When people (including philosophers) disagree about what manipulation means, what exactly are they disagreeing about?

I suggest that when we try to define a term like manipulation, we are engaging in something like interpretation in Ronald Dworkin’s sense.Footnote 12 In Dworkin’s account, interpretation involves two steps. First, an interpreter must “fit” the existing materials. To say that Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a play about cooking or fishing would be implausible, because any such interpretation does not fit the materials. It does not map onto the play. Second, an interpreter must, within the constraints of fit, “justify” the materials – that is, must make the best possible sense out of them. To say that Hamlet is a play about the evils of the welfare state would not only fail to fit the play; it would also make little sense of it. To say that Hamlet is about an Oedipal conflict is interesting and perhaps more than that.

Dworkin is speaking of interpretation in many domains, above all law, but I think that his understanding can be adapted for our purposes here. For a term like manipulation, existing understandings constrain possible definitions. We can imagine definitions that are palpably wrong, or that are far too narrow or far too broad. They are wrong, or too narrow or too broad, because they do not fit ordinary usage. A definition of manipulation that is limited to inducing guilt is both too narrow and too broad. A definition that includes reasoned persuasion is too broad. When people, including philosophers, debate what manipulation is, they are often debating what fits ordinary usage.

Within the category of definitions that are not palpably wrong, and that are not clearly too narrow or too broad, some possible definitions turn out to produce a click of recognition or assent, in the sense that they appear to make good sense, or best sense, of our intuitions or our usage. We might think that on reflection one candidate best specifies what manipulation really is, as we use that term. When people, including philosophers, debate the best definition of manipulation, they are often debating what makes the most sense of our intuitions or our usage. I am aware that these are brief remarks on a complicated topic; they are meant to signal the approach that I will be following here.

Tools and Fools

Manipulation is frequently distinguished from rational persuasion on the one hand and coercion on the other; it might be described as a third way of influencing people. If you persuade someone to buy a particular car, by giving them good reasons to believe that it will best suit their needs, you are not manipulating them. There is also a disputed relationship between deception and manipulation. Suppose that a politician uses emotionally gripping imagery in an effort to convince voters that if they vote for his opponent the country will essentially come to an end. We can easily characterize that as a case of manipulation. But it might also be seen as one of deception insofar as the politician is seeking to induce false beliefs. If we look carefully at what manipulators are doing, we will often discover that they are seeking to induce such beliefs in the people they are manipulating. That is one reason that some people deny that there is a clear or simple distinction between deception and manipulation.

I asked ChatGPT to define manipulation (prompt “Define Manipulation,” August 3, 2024), and here is what it came up with:

Manipulation refers to the act of skillfully controlling or influencing someone or something, often in a deceptive or underhanded way, to achieve a desired outcome. It can occur in various contexts, such as interpersonal relationships, politics, or media, and is usually characterized by the use of tactics that exploit emotions, perceptions, or situations to gain advantage or control over others.

That is a reasonable start. It does have the disadvantage of conflating manipulation with deception (“often in a deceptive or underhanded way”), and the word “often” introduces vagueness. Among philosophers, some of the most promising definitional efforts focus specifically on the effects of manipulation in counteracting or undermining people’s ability to engage in rational deliberation. And indeed, that will be my principal emphasis here. On T. M. Wilkinson’s account, for example, manipulation “is a kind of influence that bypasses or subverts the target’s rational capacities.”Footnote 13 Wilkinson urges that manipulation “subverts and insults a person’s autonomous decision making,” in a way that treats its objects as “tools and fools.”Footnote 14 He thinks that “manipulation is intentionally and successfully influencing someone using methods that pervert choice.”Footnote 15

The idea here is close to that of deception, but it is not the same. The idea of “perverting” choice is broader than that of “inducing false beliefs.” I have said that many acts of manipulation do that, but you can manipulate people without inducing any such beliefs. Manipulative statements or actions might be deceptive, but they need not be. My mother did not much like my father’s parents and she did not want to visit them. She and my father lived in Waban, Massachusetts, and my grandparents lived far away, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Trying to get my mother to agree to visit, my grandmother said to her, “You really should visit us. We’ll probably die soon.” My mother felt manipulated, and after getting off the phone, exclaimed to my father and me, “She keeps promising!” My grandparents lived for a very long time, but my grandmother was not seeking to deceive my mother.

Consider, for example, efforts to enlist attractive people to sell cars, or to use frightening music and ugly photos to attack a political opponent. We might think that in such cases, customers and voters are being insulted in the sense that the relevant speaker is not giving them anything like a straightforward account of the virtues of the car or the vices of the opponent, but is instead using associations of various kinds to press the chooser in the manipulator’s preferred direction. On a plausible view, manipulation is involved to the extent that it bypasses or distorts, and does not respect, people’s capacity to reflect and deliberate. Here again, it is important to notice that we should speak of degrees of manipulation, rather than a simple on–off switch.

Ruth Faden and Tom Beauchamp define psychological manipulation as “any intentional act that successfully influences a person to belief or behavior by causing changes in mental processes other than those involved in understanding.”Footnote 16 Joseph Raz suggests that “Manipulation, unlike coercion, does not interfere with a person’s options. Instead it perverts the way that person reaches decisions, forms preferences or adopts goals.”Footnote 17 Alan Wood offers a generalization, to the effect that “when getting others to do is morally problematic, this is not so much because you are making them worse off (less happy, less satisfied) but, instead, it is nearly always because you are messing with their freedom – whether by taking it away, limiting it, usurping it, or subverting it.”Footnote 18 The idea of “messing with freedom” is helpful; victims of manipulation often feel messed with in that way.

Moti Gorin argues that manipulators typically “intend their manipulees to behave in ways they (the manipulators) do not believe to be supported by reasons.”Footnote 19 On another account, “manipulation is hidden influence. Or more fully, manipulating someone means intentionally and covertly influencing their decision-making, by targeting and exploiting their decision-making vulnerabilities. Covertly influencing someone – imposing a hidden influence – means influencing them in a way they aren’t consciously aware of, and in a way they couldn’t easily become aware of were they to try and understand what was impacting their decision-making process.”Footnote 20

Of course, the idea of “perverting” choice, or people’s way of reaching decisions or forming preferences, is not self-defining; it can be understood to refer to methods that do not appeal to, or produce, the right degree or kind of reflective deliberation. If so, an objection to manipulation is that it “infringes upon the autonomy of the victim by subverting and insulting their decision-making powers.”Footnote 21 Note that undue complexity can be a form of manipulation, because it subverts and insults people’s decision-making powers.Footnote 22

That objection also offers one account of what is wrong with lies, which attempt to alter behavior not by engaging people on the merits and asking them to decide accordingly, but by enlisting falsehoods, usually in the service of the liar’s goals (an idea that also points the way to a welfarist account of what usually makes lies wrongFootnote 23). A lie is disrespectful to its objects, not least if it attempts to exert influence without asking people to make a deliberative choice in light of relevant facts. But when lies are not involved, and when the underlying actions appear to be manipulative, the challenge is to concretize the ideas of “subverting” and “insulting.”Footnote 24

Trickery, Influence, and Choice

Consider a simple definition, to this effect:

1. Manipulation is a form of trickery that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

That definition certainly captures many cases of manipulation. It should be clear that manipulation is meant to affect thought or action, or both, and so we might amend the definition in this way:

2. Manipulation is a form of trickery, intended to affect thought or action (or both), that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

Definitions (1) and (2) do not by any means exhaust the territory, but for purposes of policy and law, they are useful. They get at a key issue with manipulation, which is that it compromises people’s capacity for agency. Note that the word “trickery” is helpful in order to distinguish manipulation from coercion, lies, and deception.Footnote 25 If it is objected that lies and deception can also count as trickery, we might try a more unwieldy formulation, amending (1):

3. Manipulation is a form of trickery, not involving lies and deception, that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

We could combine (2) and (3):

4. Manipulation is a form of trickery, intended to affect thought or action (or both) and not involving lies and deception, that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

In my view, (4) is a valuable definition of a widespread kind of manipulation. But unwieldiness is not ideal, and definition (1) captures much of ordinary usage while also, I suggest, making good sense of that ordinary usage.

I emphasize that none of the foregoing definitions captures all forms of manipulation. In my view, there is no unified account of manipulation. Some kinds of manipulation do not involve trickery at all. If I make someone feel guilty in order to get them to do what I want (“I will be just devastated if you do not go to my birthday party”), I might not be tricking them, but I might well be manipulating them. If I make things very complicated, so as to prevent people from fully understanding the situation and to lead them to make the choice I want, I may or may not be tricking them, but I am certainly manipulating them.Footnote 26

We might broaden definition (1) in this way:

5. Manipulation is a form of influence that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

This definition has the advantage of including cases that do not involve trickery. It has the disadvantage of potentially excessive breadth. If you condescend to people, and treat them as children, you are not respecting their capacity for reflective and deliberative choice. But you are not necessarily manipulating them. We might take (5) as capturing cases of manipulation that (1) does not include, while acknowledging that (5) is a bit too broad.

We could, of course, amend (5) in a way that fits with (2), (3), or (4), as in:

6. Manipulation is a form of influence, intended to affect thought or action (or both), that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

7. Manipulation is a form of influence, not involving lies or deception, that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

8. Manipulation is a form of influence, intended to affect thought or action (or both), and not involving lies or deception, that does not respect its victim’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

I suggest that definition (8) captures many (not all) cases of manipulation, and although it is a bit too broad, it gets at a lot of the cases that should concern those involved in policy and law. For purposes of policy and law, definition (8) may be the best we can do (though again it does not capture all of the territory, see Chapter 6).

To understand manipulation in any of the foregoing ways, it should not be necessary to make controversial claims about the nature of choice or the role of emotions. We should agree that many decisions are based on unconscious processing and that people often lack a full sense of the wellsprings of their own choices.Footnote 27 Even if this is so, a manipulator might impose some kind of influence that does not respect people’s capacity for reflection and deliberation. It is possible to acknowledge the view that emotions might themselves be judgments of valueFootnote 28 while also emphasizing that manipulators attempt to influence people’s choices without respecting their capacity to engage in reflective thinking about the values at stake. In ordinary language, the idea of manipulation is invoked by people who are not committed to controversial views about psychological or philosophical questions, and it is best to understand that idea in a way that brackets the relevant controversies.

Is manipulation, so understood, less bad than coercion? Some people think that there is a kind of continuum here, with manipulation being less intrusive or severe. But the two are qualitatively distinct, and each is bad, when it is bad, in its own way. As Christian Coons and Michael Weber put it, “While it may be more frustrating and frightening to be ruled by a Genghis Khan (as typically characterized) or Joseph Stalin than by a David Koresh or some other cult leader, there may be an important sense … in which the latter involves a much more regrettable loss of dignity and, perhaps, our very selves.”Footnote 29

Manipulating System 1

We can make progress in understanding some kinds of manipulation with reference to the now-widespread view that the human mind contains not one but two “cognitive systems.”Footnote 30 In the social science literature, the two systems are described as System 1 and System 2.Footnote 31 System 1 is the automatic, intuitive system, prone to biases and to the use of heuristics, understood as mental short-cuts or rules of thumb. System 2 is more deliberative, calculative, and reflective. Manipulators often target System 1, and they attempt to bypass or undermine System 2. A graphic warning might, for example, get your emotions going; it might promote fear, whether or not there is anything to be scared of. The prospect of riches (for buying, say, a lottery ticket) might promote hope and optimism, even if your chances are vanishingly small.

System 1 works quickly. Much of the time, it is on automatic pilot. It is driven by habits. When it hears a loud noise, it is inclined to run. It can be lustful. It is full of appetite. When it is offended, it wants to hit back. It certainly eats a delicious brownie. It can procrastinate; it can be impulsive. It is easy to manipulate. It wants what it wants when it wants it. It can be excessively fearful. It can become hysterical. It can be too complacent. It is a doer, not a planner.

By contrast, System 2 is reflective and deliberative. It calculates. It hears a loud noise, and it assesses whether the noise is a cause for concern. It thinks about probability, carefully though sometimes slowly. It does not really get offended. If it sees reasons for offense, it makes a careful assessment of what, all things considered, ought to be done. It sees a delicious brownie and it makes a judgment about whether, all things considered, it should eat it. It is harder to manipulate. It is committed to the idea of self-control. It is a planner more than a doer.

At this point, you might well ask: What, exactly, are these systems? Do they refer to anything physical? In the brain? The best answer is that the idea of two systems should be seen as a heuristic device, a simplification that is designed to refer to automatic, effortless processing and more complex, effortful processing. If a seller of a product triggers an automatic reaction of terror or hope, System 1 is the target; if a seller of a product attempts to persuade people that the product will save them money over the period of a decade, System 2 is the target. That is sufficient for my purposes here. But it is also true that identifiable regions of the brain are active in different tasks, and hence it may well be right to suggest that the idea of “systems” has physical referents. An influential discussion states that “[a]utomatic and controlled processes can be roughly distinguished by where they occur in the brain.”Footnote 32

We need not venture contested claims about the brain, or the nature of the two systems, in order to find it helpful to suggest that many actions count as manipulative because they appeal to System 1, and because System 2 is being subverted, tricked, undermined, or insufficiently involved or not informed. Consider the case of subliminal advertising, which should be deemed manipulative because it operates “behind the back” of the people involved, without appealing to their conscious awareness. If subliminal advertising works, people’s decisions are affected in a way that does not respect their deliberative capacities. If this is the defining problem with subliminal advertising, we can understand why involuntary hypnosis (supposing it is possible) would also count as manipulative. But almost no one favors subliminal advertising, and, to say the least, the idea of involuntary hypnosis lacks much appeal. One question is whether admittedly taboo practices can shed light on actions that are more familiar or that might be able to command broader support.

The larger point is that an understanding of System 1 and System 2 helps explain why manipulation, as defined in (1) through (8) above, is often successful. The relevant trickery, or form of influence, targets System 1 or overwhelms System 2.

Falling Short of Ideals

In an illuminating discussion, drawing on Noggle’s defining work,Footnote 33 Anne Barnhill offers a distinctive account. She defines manipulationFootnote 34 as “directly influencing someone’s beliefs, desires, or emotions such that she falls short of ideals for belief, desire, or emotion in ways typically not in her self-interest or likely not in her self-interest in the present context.”

You can see that account as consistent with the central understandings in my various definitions. For example, trickery that does not respect people’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice is a form of influence that causes people to fall short of relevant ideals for belief, desire, or emotion.

But Barnhill’s definition is broader than those I have offered, and that is an advantage. You can directly influence someone’s beliefs, desires, or emotions, leading them to fall short of relevant ideals, without engaging in trickery. You can manipulate someone into falling short of ideals for (say) gratitude, romantic love, or anger, even if we are not dealing with a situation that calls for reflective or deliberative choice. Consider flirting, which may or may not be manipulative. Sometimes it is; sometimes it is not. Whether it should be counted as manipulative is illuminatingly answered by reference to Barnhill’s definition. As she says, “Flirting influences someone by causing changes in mental processes other than those involved in understanding, but flirting isn’t manipulative in all cases.”Footnote 35 Maybe the flirt is inducing certain feelings, but maybe those feelings are entirely warranted. (She’s funny, and she’s fun.) Maybe there is no manipulation at all (and reflection and deliberation may not be involved). Whether flirting is manipulative plausibly depends on whether the person with whom the flirt is flirting is being influenced in ways that cause him to have beliefs, desires, or emotions that fall short of the relevant ideals. (If she doesn’t much like him, and is just trying to get him to do something for her, she is manipulating him.)

Inducing emotions need not, but can, be a form of manipulation. Shakespeare’s Iago was a master manipulator, trying to produce anger. There are ideals for becoming angry and they can be violated. You can be manipulated to become angry or indignant. You probably have been. The android Anya, in the 2014 movie Ex Machina, was terrific at manipulating people, or at least one person, into feeling romantic love (see Chapter 8). You can fall short of ideals for falling in love. In general, the idea of “falling short of ideals” is exceedingly helpful.

Note that the standard here is best taken as objective, not subjective. The question is whether someone has, in fact, fallen short of ideals. Still, there is a problem with Barnhill’s definition, which is that it excludes, from the category of manipulation, influences that are in the self-interest of the person who is being influenced. Some acts of manipulation count as such even if they leave the object of the influence a lot better off. You might be manipulated to purchase a car that you end up much enjoying. You might be manipulated into exercising self-control – not smoking, not drinking alcohol, not drinking a diet cola. We might be willing to say that such acts are justified, especially if we are focused on human welfare – but they are manipulative all the same.

Note also that the breadth of Barnhill’s definition is a vice as well as a virtue. It seems to pick up lying and deception as well as manipulation. Perhaps we could amend the definition so as to exclude them. My own definition captures a subset of what Barnhill’s does; I suggest only that it is an important subset. And as we will see in Chapter 6, there are forms of manipulation that outrun Barnhill’s definition.

A Complication: Properly Nondeliberative Decisions

Consider this: A teenage girl is starring in a school play. The play is being performed in a place and at a time that is worse than inconvenient for her mother. When her mother tells her that she is not coming, the girl starts to cry. She says, through her tears, “This is really important to me, and all the other parents will be there!”

Is the daughter manipulating her mother?

Maybe not. A reflective and deliberative choice, on the mother’s part, depends partly on the effects of her decision on her daughter, and the intense and emotional reaction, if it is sincere, is informative on that count. The daughter has not engaged in a form of trickery that fails to respect her mother’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice. If you are deciding whether to do something that matters to people who matter to you, you should consider the emotional impact of the decision on them – and if they act in a way that produces an emotional effect on you, they might be informing you; they might not be manipulating you. As Noggle puts it, “Moral persuasion often appeals to emotions like empathy or to invitations to imagine how it would feel to be treated the way one proposes to treat someone else. Such forms of moral persuasion – at least when they are sincere – do not seem manipulative even though they appeal as much to emotion as to reason.”Footnote 36 He adds, “Nor does it seem manipulative to induce someone to feel more fearful of something whose actual dangers that person has underestimated.”

In short, some decisions are properly nondeliberative, which identifies an important reason why definitions (1) through (8) are not exhaustive, and why Barnhill’s definition picks up an important kind of manipulation – as, for example, when people are induced to feel anger or guilt when they really should not. Recall that Shakespeare’s Iago was a manipulator, and he was a master at producing emotional reactions. So we should indeed say, with Noggle and Barnhill, that manipulation can occur if people are directly influencing someone’s desires or emotions such that they fall short of ideals for having those desires or emotions.

In the case of the teenage girl and the school play, it is important to know the daughter’s state of mind. Is she feigning those tears? Is she exaggerating her emotional reaction to get her mother to come? If so, she is being deceptive, and she is also engaged in manipulation. She is making her mother think something that is not true (to the effect that she is devastated at the thought of her mother’s not showing up), and she is manipulating her to have an emotional reaction that is not justified by the situation. This is the problem to which both Barnhill and Noggle rightly draw attention. It shows that people can be manipulated in contexts that involve properly nondeliberative decisions.

If you are deciding whether to fall in love, you can be manipulated – by, let’s say, a rogue or a seducer. But your decision, if it is a decision at all, might not be, and perhaps should not be, a reflective and deliberative choice. You feel it, or you do not. If you fall in love with someone who is amazing in relevant ways, manipulation need not be involved, even if your falling in love does not involve reflection and deliberation; try the 1990 novel Possession, by A. S. Byatt, for a transporting example. But if you fall in love with someone who knows how to press your buttons, you are being manipulated. A lot of fiction is about that problem; try the 1915 novel Of Human Bondage, by William Somerset Maugham, for a searing example.

All this is true and important. But if we are seeking to get a handle on the problem of manipulation, definitions (1) through (8) capture a lot of the relevant territory, and the part of the territory that they capture is especially relevant to policy and law. If we keep definition (8) in mind, we can see an essential connection between the idea of manipulation and the idea of deception; we can even see the former as a lighter or softer version of the latter. Deceivers do not respect people’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice. With an act of deception, people almost inevitablyFootnote 37 feel betrayed and outraged once they are informed of the truth. The same is true of manipulation. Once the full context is revealed, those who have been manipulated tend to feel betrayed or used. They ask: Why wasn’t I allowed to decide for myself?

Illustrative Cases

Consider some cases that test the boundaries of the concept of manipulation.

1. Relative risk information is (highly) manipulative. Suppose that public officials try to persuade people to engage in certain behavior with the help of relative risk information: “If you do not do X, your chances of death from heart disease will triple!”Footnote 38 But suppose that for the relevant population, the chance of death from heart disease is very small – say, one in 100,000 – and that people are far more influenced by the idea of “tripling the risk” than they would be if they learned that if they do not do X, they could increase a 1/100,000 risk to a 3/100,000 risk. To say the least, that is a modest increase.

Or let’s suppose the relevant statement comes from a doctor, who is trying to convince you to take a certain medication. The doctor says: “This medication can cut your annual risk of a stroke in half.” Suppose that your background risk is 1 in 1,000, and that if you take the medication, the risk can be cut to 1 in 2,000. Suppose that the doctor is well aware that by phrasing the risk reduction as he did, he is increasing the chances that you will take the medication. Suppose that he is also aware that if he said that the medicine can reduce your risk from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 2,000, two things might happen. First, you might be confused. Second, you might think, “One in 1,000 doesn’t sound so bad, and one in 2,000 doesn’t sound a lot different. No medicine, thank you!”

The relative risk frame is a bit terrifying. It is far more attention-grabbing than the absolute risk frame; a tripling of a risk sounds alarming, but if the increase is by merely 2/100,000, people might not be much concerned. It is certainly reasonable to take the choice of the relative risk frame (which suggests a large impact on health) as an effort to frighten people and thus to manipulate them (at least in a mild sense). It is plausibly a form of trickery that fits definition (1), and it certainly fits definition (2).

It is true that any description of a risk requires some choices; people who describe risks cannot avoid some kind of framing. But framing is not the same as manipulation. There is a good argument that this particular choice does not respect people’s deliberative capacities; it might even be an effort to aim specifically at System 1. As we shall see, that conclusion does not mean that the use of the relative risk frame is necessarily out of bounds.Footnote 39 This is hardly the most egregious case of manipulation, and if it saves a number of lives across a large population, it might be justified. But it can be counted as manipulative.

2. Use of loss aversion may or may not be manipulative. Suppose that public officials are alert to the power of loss aversion,Footnote 40 which means that people dislike the prospect of losses a lot more than they like the prospect of equivalent gains. “You will lose $1,000 annually if you do not use energy conservation strategies” might well be more effective than “you will gain $1,000 annually if you use energy conservation strategies.” Suppose that officials use the “loss frame,” so as to trigger people’s concern about the risks associated with excessive energy consumption or obesity. They might deliberately choose to emphasize, in some kind of information campaign, how much people would lose from not using energy conservation techniques, rather than how much people would gain from using such techniques.Footnote 41 Is the use of loss aversion, with its potentially large effects, a form of manipulation?

The answer is not obvious, but there is a good argument that it is not, because people’s deliberative capacities are being treated with respect. Even with a loss frame, people remain fully capable of assessing overall effects. They are not being tricked. But it must be acknowledged that the deliberate use of loss aversion might be an effort to trigger the negative feelings that are distinctly associated with losses.

It is a separate question whether the use of loss aversion raises serious ethical objections. Within the universe of arguably manipulative statements, those that enlist loss aversion hardly count as the most troublesome, and in the case under discussion, the government’s objectives are laudable. If the use of loss aversion produces large gains (in terms of health or economic benefits), we would not have much ground for objection. But we can identify cases in which the use of loss aversion is self-interested, and in which the surrounding context makes it a genuine example of manipulation.Footnote 42

Consider, for example, the efforts of banks, in the aftermath of a new regulation from the Federal Reserve Board, to enlist loss aversion to encourage customers to opt-in to costly overdraft protection programs by saying, “Don’t lose your ATM and Debit Card Overdraft Protection” and “STAY PROTECTED with [ ] ATM and Debit Card Overdraft Coverage.”Footnote 43 In such cases, there is an evident effort to trigger a degree of alarm, and hence it is reasonable to claim that customers are being manipulated, and to their detriment.

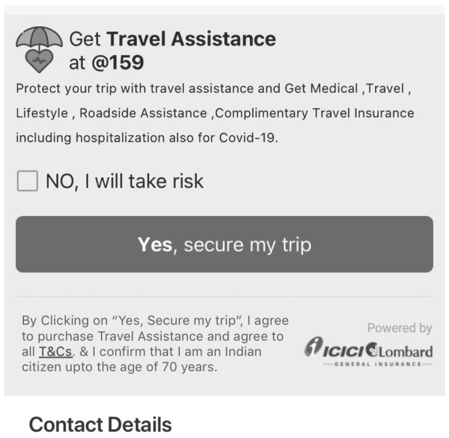

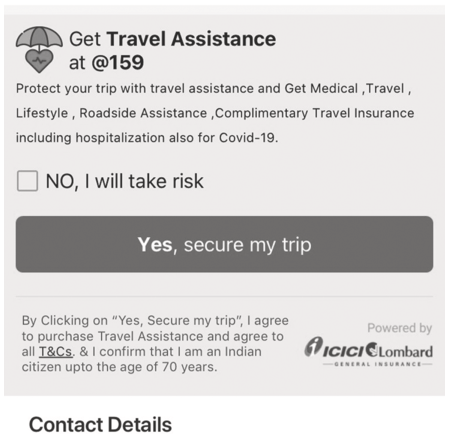

As a less egregious example from a consumer-facing company, consider the message that IndiGo, an Indian airline, presents to customers alongside the option to purchase an add-on travel assistance package (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 IndiGo Travel Assistance.

That is not the worst imaginable business practice, but it is fair to consider it to be a form of influence that does not respect people’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

3. Use of social norms need not be manipulative. Alert to the behavioral science on social influences,Footnote 44 a planner might consider the following approaches:

a. Inform people that most people in their community are engaging in undesirable behavior (drug use, alcohol abuse, delinquent payment of taxes, environmentally harmful acts).

b. Inform people that most people in their community are engaging in desirable behavior.

c. Inform people that most people in their community believe that people should engage in certain behavior.

The first two approaches rely on “descriptive norms,” that is, what people actually do.Footnote 45 The second approach relies on “injunctive norms,” that is, what people think that people should do. As an empirical matter, it turns out that descriptive norms are ordinarily more powerful. If a change in behavior is what is sought, then it is best to emphasize that most people actually do the right thing. But if most people do the wrong thing, it can be helpful to invoke injunctive norms.Footnote 46

Suppose that public officials are keenly aware of these findings and use them. Are they engaging in manipulation? Without doing much violence to ordinary language, some people might think it reasonable to conclude that it is manipulative to choose the formulation that will have the largest impact. At least this is so if social influences work as they do because of their impact on the automatic system, and if they bypass deliberative processing.Footnote 47 But as an empirical matter, this is far from clear; information about what other people do, or what other people think, can be part of reflective deliberation, and hardly opposed to it. So long as the officials are being truthful, it would strain the boundaries of the concept to accuse them of manipulation. When people are informed about what most people do, their powers of deliberation are being respected. No trickery is involved.

4. Default rules may or may not be manipulative. Default rules often stick, in part because of the force of inertia, in part because of the power of suggestion.Footnote 48 Suppose that a public official is aware of that fact and decides to reconsider a series of default rules in order to exploit the stickiness of defaults. Seeking to save money, she might decide in favor of a double-sided default for printers.Footnote 49 Seeking to reduce pollution, she might promote, or even require, a default rule in favor of green energy.Footnote 50 Seeking to increase savings, she might promote, or even require, automatic enrollment in retirement plans.Footnote 51

Are these initiatives manipulative? Insofar as default rules carry an element of suggestion – a kind of informational signal – they are not. Such rules appeal to deliberative capacities and respect them to the extent that they convey information about what planners think people ought to be buying. The analysis is less straightforward insofar as default rules stick because of inertia: Without making a conscious choice, people end up enrolled in some kind of program or plan. In a sense, the official is exploiting System 1, which is prone to inertia and procrastination. The question is whether automatic enrollment fails to respect people’s capacity for reflection and deliberation.

In answering that question, it is surely relevant that an opt-in default is likely to stick as well, and for the same reasons, which means that the question is whether any default rule counts as a form of manipulation. The answer to that question is plain: Life cannot be navigated without default rules, and so long as the official is not hiding or suppressing anything and allows easy opt-out or opt-in, the choice of one or another should not be characterized as manipulative. Note that people do reject default rules that they genuinely dislike, so long as opt-out is easy – an empirical point in favor of the conclusion that such rules should not be counted as manipulative.Footnote 52

Still, there is reason to worry that defaults can sometimes be manipulative.Footnote 53 Consider another case. A social media company defaults users into various terms with respect to privacy, newsfeed, reels, and community standards. Most of these can be changed, but they take effort. The platform’s goal is to maximize engagement, which leads to profits. With respect to reels, for example, the platform will, by default, provide offerings that increase the likelihood that users will stay online. For some, those offerings will involve conspiracy theories; for others, they will involve make-up and clothes; for others, they will involve sexually explicit videos that suit their tastes. On reflection, many users would not choose these offerings, even if they will maximize engagement. Reflecting on what is best, users would choose something else. But by default, those are the offerings that they receive. We might well say that default rules can be a kind of trickery that do not respect people’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

Or consider a different case. If people rent a car online, they will, by default, receive a variety of terms. These include insurance of multiple kinds, including an agreement to pay a large amount if the car is not returned with a full tank of gas or a full charge of electricity, and “emergency road service” that turns out to be quite expensive. These default terms do not fit the circumstances of many renters. They cost too much. But if they are offered by default, consumers will tend to accept them. “From any user’s perspective, it is best to be defaulted into an optimal situation. However, it is not reasonable to expect that others will arrange one’s choice situations in such a way or even try to do so.”Footnote 54

Default terms of this kind might be counted as manipulative, certainly if they are not transparent and if choosers cannot readily change them. It makes sense to consider regulatory responses to provide information and to allow easy, one-click opt-out.

5. Store design may be manipulative. Suppose that a supermarket is engaged in self-conscious design, with a single goal: maximizing revenue. Suppose that it places certain products at the checkout counter, knowing that people will be especially willing to make impulse purchases. Those products include high-calorie, high-sugar foods and drinks. Suppose that the supermarket also places high-profit items in prominent places and at eye-level, hoping to encourage sales. Suppose that the supermarket has accumulated a lot of data on what works and what does not. It hopes to exploit attention and salience so as to increase sales. It knows exactly how to do that.

Is the supermarket engaged in manipulation? It is fair to say so. It is using various techniques in such a way as to reduce the likelihood of reflective and deliberative choice. Manipulation is involved. If evaluation of the (manipulative) store design is not at all obvious, it is for two reasons. First, no store can do without a design; some design is inevitable, and it will have an effect (see Chapter 7). Second, some designs are very much in the interest of shoppers. We can dispute whether a revenue-maximizing design falls in that category. Still, it might well be manipulative.

6. Affect, attention, anchoring, and emotional contagion. Much of modern advertising is directed at System 1, with attractive people, bold colors, and distinctive aesthetics. (Consider advertisements for Viagra.) Often the goal is to trigger a distinctive affect and more specifically to enlist the “affect heuristic,” by which people evaluate goods and activities by reference to the affect they induce – which puts the question of manipulation in stark relief.Footnote 55

The affect heuristic was originally identified by a remarkable finding: When asked to assess the risks and benefits associated with certain items, people tend to think that risky activities contain low benefits and that beneficial activities contain high risks.Footnote 56 In other words, people are likely to think that activities that seem dangerous do not carry benefits; it is rare that they will see an activity as both highly beneficial and quite dangerous, or as both benefit-free and danger-free. This is extremely odd. Why don’t people think, more of the time, that some activity is both highly beneficial and highly risky? Why do they seem to make a kind of general, gestalt-type judgment, one that drives assessment of both risks and benefits? The answer appears to be “affect” comes first, and helps to direct judgments of both risk and benefit. Hence people are influenced by the affect heuristic, by which they have an emotional, all-things-considered reaction to certain processes and products. That heuristic operates as a mental shortcut for a more careful evaluation. The affect heuristic leaves a lot of room for manipulation. You can induce a positive or negative affect, and influence all kind of judgments, without respecting people’s capacity for reflective and deliberative choice.

Much of website design is an effort to trigger attention and to put it in the right places.Footnote 57 Cell phone companies, restaurants, and clothing stores use music and colors in a way that is designed to influence people’s affective reactions to their products. Doctors, friends, and family members (including spouses) sometimes do something quite similar. Is romance an exercise in manipulation? Some of the time, the answer is surely yes, though the question of whether people’s deliberative capacities are being respected raises special challenges in that context.Footnote 58

Acting as advocates, lawyers may be engaged in manipulation; that is part of their job, certainly in front of a jury. Suppose that a lawyer is aware of the power of “anchoring,” which means that when people are asked to generate a number, any number put before them, even if it is arbitrary, may bias their judgments. Asking for damages for a personal injury, a lawyer might mention the annual revenue of a company (say, $1 billion) as a way of producing an anchor. That can be counted as a form of manipulation, because it does not respect people’s deliberative capacities. If a salesperson uses an anchor to get people to pay a lot for a new motor vehicle, manipulation is also involved, and for the same reasons.

The same can be said about some imaginable practices in medical care. Suppose that doctors want patients to choose particular options, and enlist behaviorally informed techniques to manipulate them to do so. An example would be to use the availability heuristic, by which people assess risks by asking whether examples come readily to mind. If a doctor uses certain examples (“I had a patient who died when …”), we might have a case of manipulation, at least if the examples are being used to bypass or subvert deliberative judgments.

Or return to certain uses of social media – as we saw, for example, in 2012, when Facebook attempted to affect (manipulate) the emotions of hundreds of thousands of people though the display of positive or negative stories to see how they affected their moods.Footnote 59 Numerous practices on social media platforms, however familiar, can be counted as manipulative in the relevant sense.

A Checklist

Anne Barnhill has devoted a lot of time and effort to defining manipulation, but she is aware that efforts at definition are challenging, and that it may not be possible to come up with a definition that commands a consensus.Footnote 60 She urges that instead of worrying about whether a practice fits the definition, we might ask questions that might illuminate why some people see it as manipulative. Here are some of her questions, slightly revised:

Is the influence covert or hidden?

Does the influence target, or play on, psychological weaknesses or vulnerabilities? These could be psychological weaknesses or vulnerabilities in the specific targeted individual or of people in general.

Does the influence subvert people’s self-control?

Does the influence fail to engage people in deliberation or reflection? If so, is deliberation or reflection called for in the context?

Does the influence cause people to have emotional reactions? Are these appropriate or inappropriate emotional reactions, given the context?

Does the influence undermine rationality or practical reasoning in some way?

A checklist of this kind is helpful, because the questions it asks may be easier to handle than the question whether some statement or action counts as manipulative. Many cases of dark patterns, understood as deceptive or manipulative practice online, can be handled by reference to such questions, even if we struggle to decide whether those cases involve manipulation. We will get there in short order.