Each month, hundreds of cases of rape and sexual assaults are being reported. These despicable crimes of sexual violence are being committed against our women, girls, and babies. On this note, I therefore declare rape and sexual violence as National Emergency. With this declaration, I have also directed the following … With immediate effect, sexual penetration of Minors is punishable by LIFE IMPRISONMENT. (Maada Bio Reference Maada Bio2019)

What happens when state institutions and citizens have different views about what constitutes violence in relationships with and between minors and how it should be dealt with?Footnote 1 This chapter discusses the Sexual Offences Act (SOA) and the Sexual Offences Amendment Act (SOAA), and the school ban (SB) on visibly pregnant girls. It considers the ways in which the criminal justice system and its institutions treat violence in relationships involving minors. Here, the main (often only) focus lies on sexual relationships that are regarded as violent irrespective of the perspectives of those involved. The chapter commences with an analysis of the legal regulations of the SOA and how they are perceived among research collaborators. It shows how, based on the recommendations of the TRC (2004a) in post-war Sierra Leone, development agencies, lawmakers, and politicians discursively framed and justified the SOA by positioning the people implicated in sexual offences cases within an ‘imagined otherness’ (Carlbom Reference Carlbom2003: 57; Sartre Reference Sartre2004; Ahmed Reference Ahmed2014: 42–3). Thereafter, there is a discussion of the political aspects of this act and its amendment as well as the subsequent school ban (Mahtani Reference Mahtani2016; Villa Reference Villa2017). I also describe the structures of reporting and the trajectories of cases of sexual offence. To be effective, the criminal justice system renders persons and acts abstract. It constructs ‘constitutive outsides’ (Hall Reference Hall, du Gay and Hall1996: 3; Esposito Reference Esposito2011). When minors are involved, sentences are no longer relative and relational. The courts would not consider the cases, for example, of Issa against Josephus or Apsatu against her husband. Rather, they examine whether there is a clear perpetrator–victim relationship between defendant and claimant. These abstractions seek to provide clarity without considering the complexity of social and emotional factors. The chapter also explains the role of age in public perception as a social factor and how this differs from the numerical certainty required by legal frameworks. It provides the reflections and criticisms of citizens and criminal justice personnel, and puts these in conversation with the analysis.

The Sexual Offences Act and the School Ban on Visibly Pregnant Girls

A Sexual Penetration Case

Principal Magistrate Binneh of Freetown Magistrate’s Court No. 1 presides over 15–30 cases daily. If the power works, several rows of fans are turning on the wooden-tiled ceiling among two flickering light-bulbs, one in the front and one in the back of the room. If, as on most days, the power is interrupted, litigants, their families, journalists, and criminal justice personnel wave leaflets and fans in front of their faces to make the heat bearable. The large room is divided into several sections. On a raised podium in the front is the magistrate’s seat facing the courtroom. A door to its left leads to the Magistrate’s chambers, where he presides over particularly sensitive cases. A caged space to its right is the witness stand. In front of his podium, there is a small desk reserved for his two paralegals, women in their early twenties; on the table are piles and piles of case files. Then facing the judge’s podium follow rows of comfortable leather seats and tables for the lawyers. On the left-hand side are three rows of benches and tables reserved for police officers and Rainbo Centre personnel. The second half of the room is divided as follows. Next to the entrance door, there are three rows of benches for ‘journalists only’, which is where I usually sit. In the very back, there are rows for litigants and family members. On the right and farthest away from the door is a small bench on which the accused are seated, handcuffed together in pairs of two. Finally, in the middle of the room is a fenced-in space where the accused must stand when their case is heard.

When I enter the court on 17 June 2016, Magistrate Binneh is just about to open another case dealing with sexual penetration. He calls the accused. After the police officer has uncuffed him, the young man is called to enter the fenced space in the middle of the courtroom. But because his hands are shaking so much, he is unable to open the small door to enter the stand without the help of the police officer. Magistrate Binneh reads the accusation, ‘sexual penetration of a minor’, and asks the young man how he pleads: na so I bi or notto so I be? [‘how do you plead?’]. When asked to speak, the accused starts shaking uncontrollably, and the silence of the courtroom lifts under the murmurs of those present. I can hear his teeth chattering. He looks no older than 15 or 16. His terror invokes sympathy and pity among those present: ‘Sahr, this man is only a small boy’, remarks one woman. ‘Look at him, he is so afraid’, states another. After Magistrate Binneh demands silence using his gavel, he says: ‘You have been declared an adult at the police station. I will send you for age assessment, but I do not believe you to be under 18. If you have a lawyer, you want to ask for a birth certificate. For now, you are going back to prison’. He adjourns the case to the following Tuesday. The accused keeps looking at what may be his parents, tears running down his face. He never enters his plea. Upon returning to the accused’s bench, the other accused persons hold him around the shoulder. It looks as though they are preventing him from falling off the bench, but it is unclear whether this is to comfort or threaten him.

The following week, the case is heard in chambers. The alleged victim is a 17-year-old girl [the same age as Ester in Chapter 6], who is seven months pregnant. The accused is asked to face the wall during her testimony. The accused has such severe stomach pain that he has trouble standing. He frequently drops on his knees until the police officer cautions him to stand up again. The accused then struggles to get back on his feet until his knees give in once more. The surveillance police officer says he has had this pain since being transferred to the remand block in Pademba Road Prison, to which a man says jokingly: ‘This prison will kill you, just wait. First the soup is like water running down your arm and then it runs right back out of you.’ Another lawyer also not involved in the case turns to the alleged victim and says: ‘Ah Salone, na so you treat us men. First you seduce us, then you punish us?’

When testifying, the alleged victim explains that she had sex with the accused regularly between December 2015 and March 2016 because he was her boyfriend at that time. When she was asked how it made her feel, she said: ‘I felt fine’. She explains that eventually she became pregnant and that once her pregnancy was visible, her teacher took her to the police station to report the matter. From there, they went to the hospital to obtain the medical report that stated that her hymen was broken and that she had been found to be pregnant. Subsequently, and in accordance with the ‘school ban for pregnant girls’, she was expelled from school.

The accused is from a poor family and cannot afford a lawyer. He has not yet been assigned a free lawyer from the Legal Aid Board because his case has not reached the High Court. Magistrate Binneh says that the accused should try to prove he is underage but that he has no time to do special things for him because he has far too many cases to preside over. Without proof, he cannot be tried as an offender in a juvenile court rather than as an accused in a regular court. Binneh asks the accused when he was born, and he replies: ‘8 September 1999’. A week later, after an informal age assessment that was unable to verify his age below 18, Binneh says that he has no choice but to send the matter to the High Court.

The case is called at the High Court about six months later and is concluded in three hearings. In all hearings, the girl and boy confirm that they are in a relationship. When I speak with her, the alleged victim consistently smiles and laughs when describing being with the accused. It is very clear that they are a couple who were together with the blessing of those family members living under the same roof. On 19 February 2017, the accused is convicted and sentenced to eight years in prison.

What Is the Sexual Offences Act and Why Was It Implemented?

This case is a consequence of the SOA. The SOA was the product of the recommendations of the TRC (2018) and the research of IOs, NGOs, and local women’s movements, which pointed to large-scale sexual trafficking, sexual slavery, rape, and sexual assault during and after the civil war, particularly involving minors. The TRC report highlighted the high numbers of young girls being sexually abused by much older men (TRC 2004a; 2004b). It pointed to the difficulty girls experience when reporting such issues due to the prevalence of informal or ‘friendly’ settlements (Chapter 7). The report further made a strong recommendation to raise the age of maturity to 18. Jointly promoted by the Parliamentary Human Rights Commission, the Law Reform Commission, the government, and various partners, the SOA was ratified in 2012. It raised the age of sexual consent to 18, criminalised all sexual relationships with minors, and increased sentences to a maximum of 15 years. Marriage would no longer be a valid defence. In 2019, following the declaration of a national emergency on rape and teenage pregnancy, the SOA was amended and now includes the possibility of life sentences for perpetrators. It also lowers the age of criminal responsibility and now allows boys as young as 12 to be sentenced for sexual acts (Government of Sierra Leone 2019).

Prior to the ratification of the SOA, Sierra Leone regulated sexual violence against minors by the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act (PCAA) of 1926. Section 6 of the PCAA defined unlawful carnal knowledge – penetration of the victim’s vagina by the penis of the accused – of a girl below 13 as a crime that carried a punishment of 15 years of imprisonment, irrespective of her consent. Section 7 stated that if a girl was above 13 but under 14 years, the sentence should be reduced to two years of imprisonment. For any sexual crime committed against a person above 14 years, consent was a possible defence.

To bridge this gap between 14 and 18, section 1, part 1 of the SOA defines a child as any ‘person under the age of 18’. Part 1, section 4 of the SOA states: ‘a person below the age of 18 is not capable of giving consent … it shall not be a defence to an offence under this Act to show that the child has consented to the act that forms the subject matter of the charge’. The Act describes sexual penetration (SP) as ‘any act which causes the penetration … of the vagina, anus or mouth of a person by the penis or any other part of the body of another person, or by an object’. SP is an offence ‘liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment not less than five years and not exceeding fifteen years’. Moreover:

A person who –

(a) touches a child in a sexual manner; or

(b) compels a child to touch the accused person’s own body in a sexual manner …

is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment not exceeding fifteen years.

Consequently, as anyone under the age of 18 is legally regarded as a child, any sexual activity with them constitutes a criminal offence with a prison sentence of up to 15 years.

Political Developments That Influenced the SOA

The development and ratification of the SOA dovetailed with former president Ernest Bai Koroma’s re-election platform (The Agenda for Prosperity 2013–2018).Footnote 2 In its attempt to address donor interests and development agendas, this strategy focussed inter alia on the girl child and on the ‘fight against teenage pregnancy’ that was formulated in the National Strategy for the Reduction of Teenage Pregnancy (2013–2015) (Government of Sierra Leone 2013).Footnote 3 In the post-war era, Koroma’s efforts to promote Sierra Leone as a nation in which development goals were a top priority and which was therefore deserving of development funding seemed to be undercut by young people’s fluid relationships and their sexual experimentation. Consequently, young people’s behaviours and diverse relationships were less and less appreciated. Young people were reconfigured as unruly subjects interfering with government attempts to demonstrate that in Sierra Leone sex was sufficiently policed.

In aligning some of the TRC recommendations for preventing violence with the concerns of donor bodies for educating girls and preventing early marriage and teenage pregnancy, the SOA was supposed to solve two problems at once. By criminalising all sexual relationships with minors and removing perpetrators from society, it was thought that teenage pregnancy and rape could be stopped. Koroma’s successor, the current president Maada Bio, followed in his footsteps by declaring a national emergency on rape and sexual violence and by subsequently ratifying the SOAA.Footnote 4 The SOAA makes further age-related distinctions. A ‘child’ – which, according to chapter 44 of the Children and Young Persons Act, ‘means a person under the age of fourteen years’ (Government of Sierra Leone 1945) – ‘who engages in an act of sexual penetration on another child or rape commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment of not less than five years (5) and not more than fifteen (15) years imprisonment’ (Government of Sierra Leone 2019: section 4, no. 8). A ‘young person’, on the other hand, means ‘a person who is fourteen years of age or upwards and under the age of seventeen years’ (Government of Sierra Leone 1945). According to the SOAA, a young person ‘who engages in an act of sexual penetration or rape on another person commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment of not less than ten (10) years to life imprisonment’ (Government of Sierra Leone 2019: section 4, no. 8). Finally, ‘a person above the age of a youth who engages in sexual penetration or rape on another person commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment of not less than fifteen (15) years to life imprisonment’ (Government of Sierra Leone 2019: section 4, no. 8).

While both presidents were responding to the urgent need to address high levels of rape and sexual violence,Footnote 5 the resulting laws have tremendous implications for desire and for the consensual sexual relationships of young people as well. Indeed, as I have argued elsewhere, age-of-consent law creates multifaceted challenges. If the age is set too high, it undermines the agency of young people. Conversely, if the age is set too low, it does not provide adequate protection for vulnerable young people (Schneider Reference Schneider2019c).

By setting the minimum age of consent at 18 and, at the same time, passing laws that can convict people below that age for sexual acts, Sierra Leone has created a gendered paradox – even though the laws are technically gender-neutral. Young girls cannot consent to sexual relationships, yet young boys can be sentenced for them.

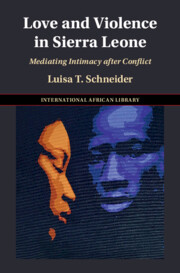

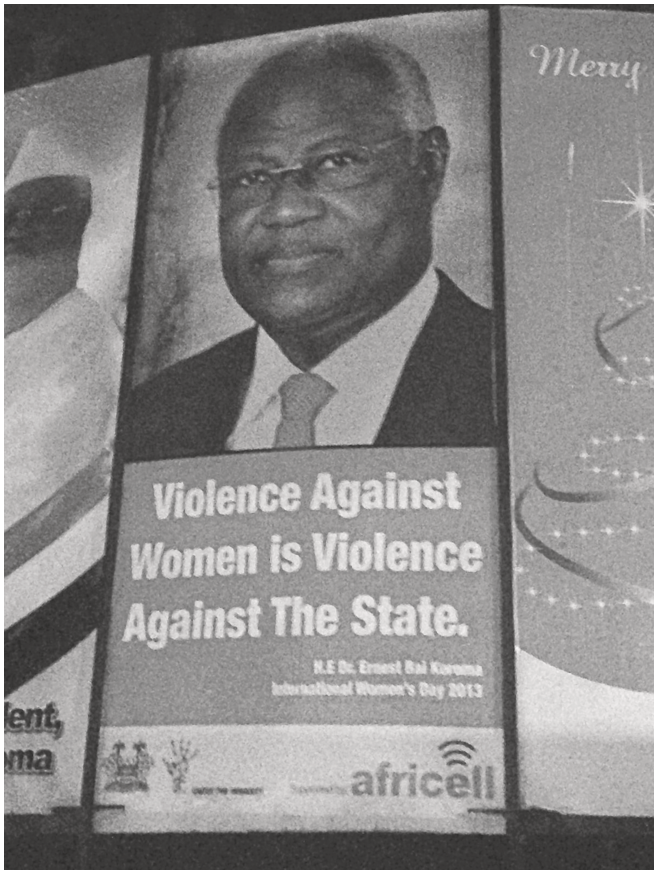

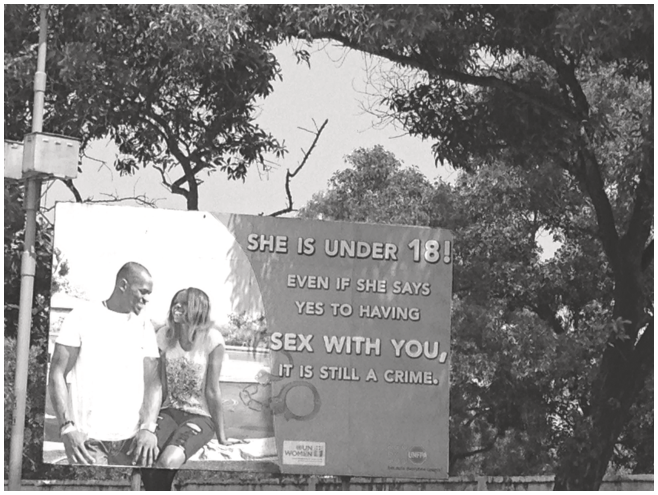

During Koroma’s presidency, increased campaigning began around young girls’ and boys’ sexual behaviour. A poster by UN Women and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (see Figure 8.1), which was displayed in western Freetown, was addressed to men and boys and told them to abstain from having sex with girls legally unable to consent. Although she is depicted in the picture, the girl has no decision-making power. Her opinion and her possible desire do not matter. It is men who must decide how to act, while girls’ sexuality is at the mercy of their decision. The poster does not show a girl in a school uniform or a man who is an elder. Rather, it depicts a young couple with a much smaller age difference. Interestingly, while the law is written in a gender-neutral manner, the kind of attitude displayed on the poster carries over into sentencing. What magistrates and judges consider is whether boys have committed a crime against girls who are unable to consent, not vice versa. To my knowledge and that of my research collaborators, no woman has ever been convicted for sleeping with an underage boy.

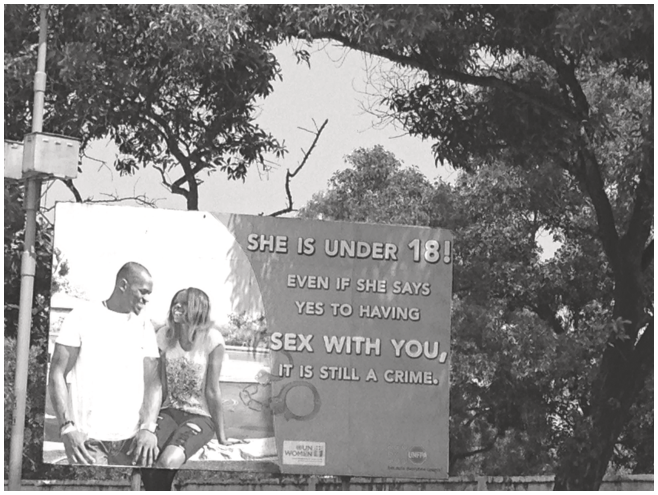

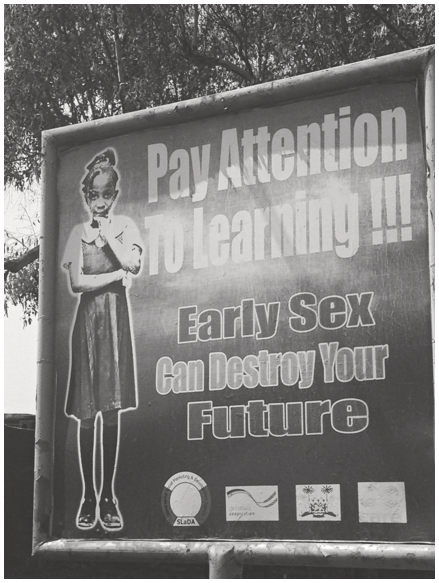

Another poster, produced by the Sierra Leonean Development and Media Agency, the government, and German partners (see Figure 8.2), depicted sex as a distraction and as destructive of girls’ education and their futures.Footnote 6 The two posters taken together show that girls are addressed and warned about sex prior to puberty. Once they have entered puberty, they are silenced. The communication is not conducted with them, but about them. It seems that institutions find it easier to forbid men to engage in sexual activity than to address female desire. Moreover, these posters do not actually speak about rape. Rather, they refer to sexually active young people. However, the SOA, the SOAA, and the campaigning around them did not manage to end teenage pregnancies. This continues to be regarded as one of Sierra Leone’s biggest problems.

The School Ban on Visibly Pregnant Girls

UNICEF Sierra Leone’s main page on its website states:

In Sierra Leone, teenage pregnancy and child marriage are common. According to the country’s 2013 Demographic and Health Survey, 13 per cent of girls are married by their 15th birthday and 39 per cent of girls before their 18th birthday … Teenage pregnancy reduces a girl’s chances in life, often interfering with schooling, limiting opportunities, and placing girls at increased risk of child marriage, HIV infections and domestic violence. According to the World Health Organization, teenage pregnancy is also a leading cause of death for mothers in Sierra Leone. Data from 2015 show the country’s maternal mortality rate is at 1,360 deaths per 100,000 live births. (UNICEF 2017)Footnote 7

Sabrina Mahtani, writing for Amnesty International, states that ‘even before Ebola broke out in late 2013, Sierra Leone had one of the highest teenage pregnancy rates in the world, with 28% of girls aged 15–19 years pregnant or having already given birth at least once’ (Mahtani Reference Mahtani2016). During the Ebola pandemic (2013–16), studies reported an increase in teenage pregnancy. According to one such study by the Secure Livelihoods Consortium, UNFPA surveys indicated that 18,119 teenage girls became pregnant during the Ebola outbreak (Mahtani Reference Mahtani2016). These studies have been sharply contested by local health workers and by Rainbo Centre personnel who, in interviews with me, described these statistics as political fabrications. ‘Before the Ebola outbreak, most institutions did not gather data’, explained a former Rainbo Centre employee. ‘We only had data from the war and the TRC. During Ebola, suddenly statistics became very important. But it seemed as if they showed a devastating trend, when really they showed nothing new’.

Nevertheless, government officials relied on these data and likened the ‘teenage pregnancy epidemic’ to the Ebola pandemic (Seema Reference Seema2016; Whyte Reference Whyte2016). This second ‘disease of social intimacy’ (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Amara, Ferme, Kamara, Mokuwa, Sheriff, Suluku and Voors2015: 1) was presented as threatening the prosperity and well-being of all Sierra Leoneans. Even before the pandemic, girls found to be pregnant were regularly banned from attending school and sitting exams. However, this practice had never been formalised. In April 2015, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology published a statement that formally banned pregnant girls from mainstream education and from taking exams. The ban took effect immediately and was carried out by means of searches and physical examinations of girls. Although international donors proposed an alternative ‘bridging system’ (Mahtani Reference Mahtani2016) in the form of special education for pregnant girls in different schools, this has never been fully realised.

How Is the Effectiveness of the SOA and the SB Ensured?

To function, the SB and the SOA require the participation of citizens. By themselves, state institutions would have been largely ineffective in policing young people’s relationships. They are unable to enter communities or households without the assistance of citizens. They do not have the resources to do so and can only act if they are called upon. Furthermore, different mediation systems have their own jurisdictions. According to Sally Falk Moore, ‘an inspection of semi-autonomous social fields strongly suggests that the various processes that make internally generated rules effective are often also the immediate forces that dictate the mode of compliance or noncompliance to state-made legal rules’ (Moore Reference Moore1973: 721). And, as we have seen in previous chapters, many citizens have ambivalent opinions about state institutions and take great care to keep the state at bay while informally and internally regulating disputes. State laws differ extensively from community procedures and point to different perceptions of gender, violence, and punishment. Compliance with them is therefore not a given.

Nevertheless, the reporting of sexual penetration cases has increased dramatically, from 95 reports in 2011 to over 2,398 in 2015 (FSU crime statistics). But how was it possible to mobilise enough citizens to render the laws effective? How could their reach encompass the different jurisdictions of households, communities, and the criminal justice institutions? To be effective, state institutions needed to persuade citizens that the laws were in their best interest. This required a discursive framing and subsequent calls to action. What needed to be created was the idea of an imaginary future Sierra Leone free of teenage pregnancy and rape. But such a future could only come about, it was claimed, by the smooth implementation of these laws. And their smooth implementation, in turn, was made the responsibility of citizens.

Sex as Pollution That Threatens Familial Control over Sexuality and Reproduction

Subsequently, state personnel adopted a language of pollution and described all sexual activity among young people, irrespective of consent or protection, as destructive. Consider the following statement by a politician whom I interviewed in September 2016:

We have a disease here in this country. All these young people go out and have sex without no consideration for nobody. They cannot stop that, and then they get pregnant even when still in school, and that is a hopeless situation for the parents and for the development of this country. So, we need laws which stop all that because only when there is fear, actual fear of a sentence, will people’s actions change.

This politician’s concern was not primarily for the two persons involved in potential sexual activity, but with the consequences for their families and for society. Hence, it taps into local notions of gender relations. Shanti Parikh has argued that the defilement law in Uganda, which also raised the age of consent to 18, is in effect an attempt to help fathers regain authority over their daughters’ sexuality and sexual decision-making (Parikh Reference Parikh2012: 1779). ‘It is plausible’, says Deniz Kandiyoti in her work on patriarchal systems in Africa, that ‘the emergence of the patriarchal extended family, which gives the senior man authority over everyone else … is bound up in the incorporation and control of the family by the state … and in the transition from kin-based to tributary modes of surplus control’ (Kandiyoti Reference Kandiyoti1988: 278).

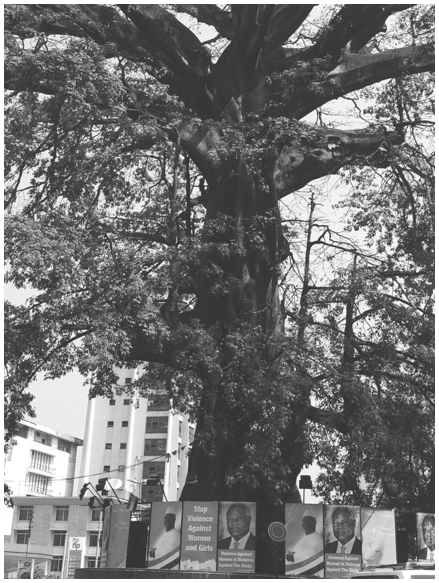

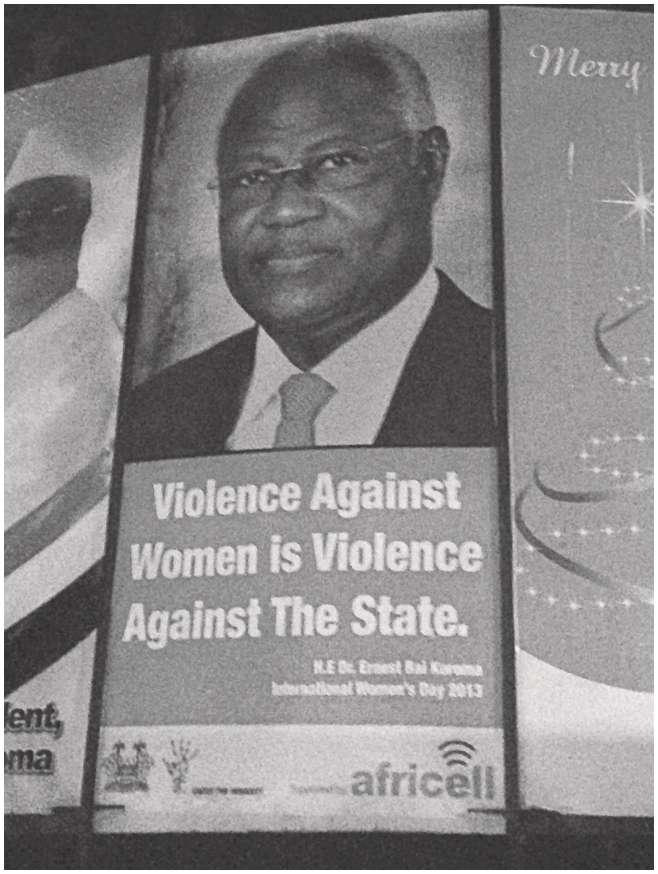

The Sierra Leonean state thus sought to build its gendered ideals on those of communities and attempted to speak to them to mobilise their support. Subsequently, the president was urged to accept the role of guardian for all Sierra Leonean girls. This can be interpreted as an extension of the power of the paternal figure over the sexuality of those under his guard. The president, the father of all households, would become the ultimate guardian of young girls’ sexuality and reproductive capacities (Figure 8.3).

The construction of the president as ‘guardian of girls’ was made possible by the TRC report, which stated:

316. Women and girls were the deliberate targets of sexual violence and rape by all the armed groups during the conflict. Women continue to be victims of gender-based violence. The Commission has noted the submissions made by women’s groups, which point to the failure of successive governments to protect women and girls during the conflict and post-conflict periods.

317. The Commission recommends that the President, as the ‘Father of the Nation’ and as the Head of State, should acknowledge the harm suffered by women and girls during the conflict in Sierra Leone and offer an unequivocal apology to them … This is an imperative recommendation.

Thus, when Koroma claimed that ‘violence against women is violence against the state’ (see Figure 8.4), he was identifying with the subject position of guardian of women and girls. Simultaneously, he created an ‘other’ in the violent perpetrator, against whom the state could position itself and against whom it could unite to protect those under its guard. In a similar vein, President Maada Bio was quoted as stating:

On a sad note, thousands more cases of rape and sexual violence were unreported because some families and communities practise a culture of silence or indifference about sexual violence, leaving victims traumatised. He noted that alarmingly, the perpetrators were getting younger and their acts getting more violent and bestial …

He said that government would engage communities and civil society in dialogues to eliminate the culture of compromise and silence around sexual violence, adding that the country must put an end to the scourge that was slowly wrecking the nation.

‘On this note, I, therefore, declare rape and sexual violence as National Emergency’.

With the guardian installed, the next step was to pave the way for political action. To this end, ideas of safety, security, and prosperity were used to create the image of a future community free of violence and teenage pregnancy. Then a ‘threat’ to this wonderful future was conjured up by likening sex among young people to an infectious disease that polluted this possibility.Footnote 8 The issue here is not whether the threat is real and contagious. It may be entirely separate from the empirical reality. Rather, the threat is a ‘structural function’ that justifies the execution of violence against this ‘other’ (see Žižek Reference Žižek2008).Footnote 9 By being assigned a function, namely that of ‘saving the girl child’, groups of people could form a community. To enable this ‘community of Sierra Leonean citizens’ to act, the SOA was set up in such a way that anyone could report a case to the police. The official campaigns around the Act promoted the view that it was the duty of all Sierra Leoneans to ensure that sex did not take place with minors. By reporting pregnant girls and boys who have sex with girls to state institutions, communities made it possible for these institutions to extend their reach and effectively police young people’s sexuality. The criminal justice system could now survey households and bedrooms, ban pregnant girls from school, and imprison boys who slept with these girls. Such actions seemingly expelled the ‘threats’ from the community and prevented them from re-entering and ‘spreading’ (Esposito Reference Esposito2011). By these means, state institutions helped form communities that would ensure the efficacy of its laws.

Responsible Citizens Report

However, not every Sierra Leonean started reporting. In the case described at the start of this chapter, those present were very sympathetic towards the accused. People usually regard reporting others’ ‘private business’ as kongosa, equivalent to ‘name spoiling’ and thus ‘antisocial behaviour par excellence’ (Szanto Reference Szanto2018). But in the eyes of the state, those who do not report, the ‘families who practise a culture of silence’ (in Maada Bio’s words) and who thus obstruct the workings of the SOA, are separated out and made to form a ‘them’, as opposed to the ‘respectable citizens’ who do report (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2016: x) – an imagined ‘us’. It is not surprising therefore that most cases are not reported. After all, the victim is part of ‘them’, part of the persons who had sex.

For the family of the girl, reporting a case to the police is often a last resort. If, after a pregnancy occurs, negotiations with the family of the man or boy fails, or if the father of the child is deemed to be economically unable or socially unfit to care for the girl and her baby, they may turn to the police. An employee of the Rainbo Centre said:

Most cases brought to us are statutory rape. Many only go once a pregnancy occurs and the family feels responsible to act. They need someone to take responsibility for the pregnancy to fend off shame from the family and ensure that the child will have a name. Many are frustrated if they paid for their daughter to go to school and then the daughter ends up pregnant and stops her education. They want someone to remunerate them for their expenses.

As I have shown, this remuneration usually takes place in informal settlements between the families involved. In the case of ansa bɛlɛ, it fends off shame for the pregnancy out of wedlock and assigns a father to the baby (Chapter 3).

The state’s campaign to promote reporting has mainly been successful among those citizens who work for state institutions or interact with them frequently, such as teachers and pastors (Chapter 7). They tend to have faith in the ideas of human rights and the future of the nation-state, which are enshrined within this ‘ideoscape’ (Appadurai Reference Appadurai1990: 296). State employees, moreover, frequently come in contact with human rights principles. Because they engage with large numbers of people, the state’s campaign is effective even if it is unable to capture the masses. Reporting often takes place once a pregnancy occurs or if the relationship has become public. George (47), a middle-school teacher, told me: ‘We the teachers are especially important. Whenever you see a pregnancy of a girl having sex and falling astray, you must report so for the greater good’. And Madame Conteh (34), a high-school teacher, said: ‘We cannot rely on the girl or the parents to report. Maybe he is the boyfriend or maybe they will settle’.

These citizens who report act as a vanguard, helping build the ideological foundations of these laws, which then create their very subjectivities and shape their actions (Althusser Reference Althusser1972: 11). This allows them to report on sexual activity ‘for the greater good’. In their practices of reporting on those who have sex, they doggedly attempt to create this world of tomorrow, thereby turning the destructive act of kongosa into an act of true faith (Kierkegaard Reference Kierkegaard1983).Footnote 10

Case Trajectories from the Police Station to the Magistrate’s Court

After sexual penetration cases have been reported, the police and, later, the courts need to determine whether sex has taken place. At the police station, the alleged victim gives a first-person statement, which is included in the police report. Then the girl is sent to the Rainbo Centre, where a medical examination is conducted. Besides screening for diseases and injuries, this examination tries to establish whether the girl has a ruptured hymen. In the absence of forensic testing, it is the Rainbo Centre’s medical report that plays a main role in determining an accused’s fate. If the report says the hymen of the alleged victim has been broken, though it is unable to tell under which circumstances or when, a conviction is almost certain. This is so in the majority of cases. Then the accused is called to the station to make his statement. After that, he is usually sent to the remand block in Pademba Road Prison or, if he is very young, to Dems, the remand home for minors.

All sexual violence cases as well as matters involving minors are handled in chambers. Only the opening of cases is conducted in open court. All sexual penetration cases follow the same pattern. Those present in the chambers include the witness, the interrogating police officer of the FSU, the accused, sometimes journalists, and, if the accused has representation, his lawyers. The paralegal hands the case file to the magistrate. They then leave and close the door. During proceedings, the magistrate copies down the witness’s statement word by word.

The police officer conducts the ‘prosecution of the witness’. After the witness is sworn in, either with the Quran or the Bible, the witness is asked whether she recognises the accused person or persons. She is cautioned not to address them by their names but to refer to them by numbers (from one onwards). Then she is asked whether she remembers the date when the incident happened. After she confirms the date, she is asked to explain in detail the sequence of events: ‘Tell us step by step what did happen’. The FSU officer has prepared the witness prior to her testimony.Footnote 11 They may ask follow-up or clarifying questions after or during the interview. After describing the incident, the alleged victim is asked: ‘How did you feel after the incident?’ and ‘Did you witness anything on your body?’

Determining whether penetration has taken place is the prerequisite for a conviction. The length of the sentence is then determined by means of the last two questions: ‘How did you feel?’ and ‘Did you witness anything on your body?’ Here, alleged victims are asked to speak loudly and clearly not only about ‘having sex’ but also about the specific acts involved as well as how they felt about them. Witnesses usually either say ‘I felt fine’, ‘I was enjoying’, or ‘I felt pain’. The first two replies may lead to a decreased sentence. A pregnancy counts as an aggravating factor. The second question, ‘Did you witness anything on your body?’, is answered with ‘blood and white fluid’, a variation of these, or ‘no’. If the answer is no, a defence lawyer may contest her statement by saying that sex did not take place and that she had had sexual intercourse before, which might be accepted as a mitigating factor.

Chambers are supposed to create a safer and more private environment than open court. In effect, there are often up to ten people in the room, some of whom are not connected to the case. Journalists often answer phone calls or engage in unrelated casual conversations with each other. Lawyers may enter and discuss (confidential) cases at any moment. If a child cruelty matter or a matter of unlawful carnal knowledge is heard – thus cases where the alleged victim is under 14, often very young – the prosecutor and magistrate are patient, calm, and focussed. The alleged victim can take her time and is frequently given encouragement. However, in sexual penetration cases where the alleged victim is between 14 and 18, the situation is very different. Then, alleged victims are often shouted at if they do not speak loudly or clearly enough or if they add too much or too little detail. Furthermore, because the magistrate is personally responsible for taking notes, he often interrupts or halts the testimony by saying ‘Move on, this is not relevant’ or ‘Only talk about the day of the act, how it happened, and what happened after’. The court is not interested in detailed accounts and urges the witness to speak only about the act in question and those performing the act. After testifying, the witness is asked to identify her medical report and to agree to its content.

While the alleged victim is speaking, the accused must turn away from her and face the wall. He is not allowed to speak until the witness has concluded and signed her statement. (I have never seen a witness reading her statement before signing it.) The accused is then allowed to turn around. If a lawyer is present, they will conduct the cross-examination, which usually includes questioning the alleged victim’s age, virginity, and intentions, and confirming that the act took place (‘I put it to you that you are not below 18’; ‘I put it to you that you were not a virgin’; ‘I put it to you that you never lay down with this man’). If no lawyer is present, the accused may cross-examine the witness. Accused persons are usually unable to counter the statements. Some claim that they were never there. Others say that what happened was ‘different’, without explaining how, or that the alleged victim begged them to do whatever it is they did. After gathering the statements by the police, the alleged victim, and the accused, the magistrate determines whether there are sufficient grounds for the case to be tried in the High Court or whether it should be dismissed.

Bail may be given only after the Magistrate’s Court’s investigation is complete and after the witness has given testimony. A magistrate who wishes to remain anonymous said:

People have the tendency to interfere with prosecution witnesses. That’s why we are a bit hesitant to put accused persons on bail immediately after they are brought to court. So, we get the prosecution to come forth with their witnesses, principally the start witness, who is the victim. It is after the victim has testified that we can consider the question of bail.

Bail is often set at SLL 50 million (GBP 4,590.07), which means that accused persons can bail themselves out by paying SLL 500,000 (GBP 45.90) to the court clerk. In the unlikely event that a person is able to pay bail in full, the amount has to be paid to the National Revenue Authority (NRA). It is illegal to bribe magistrates or judges, but bribery in police stations and prisons and of clerks is common, even expected.Footnote 12 In many cases, the defendant needs to provide surety to be granted bail. In Sierra Leone, this is a person who signs on behalf of the defendant, accepting accountability for the charge in case the prisoner jumps bail. Finding such surety is difficult. John, a prison social worker at Don Bosco, told me of one case where the charged person ran away and the sentence was transferred to the surety, who then spent eight years in prison. A judge explains: ‘Because of pressure from human rights activists and civil society representatives and the media, most of us are always afraid to put accused persons on bail when such allegations are made against them even when the matters do come to court’. Many of the men and boys I spoke to at Pademba Road Prison had not been granted bail even though the investigations at the Magistrate’s Court had been concluded. Since the implementation of the SOAA, cases can proceed directly to the High Court, and accused individuals are no longer eligible for bail.

Trial through Abstraction: Victims and Perpetrators

As we have seen, courts cannot consider contextual factors. Unlike communities, they cannot analyse a person’s comportment or personality. They are strangers to the people they deal with. When writing about sexual violence, Steffen Jensen remarks that ‘law to a large extent cannot work with unsettled categories; something needs to be held constant’ (Jensen Reference Jensen2015: 101). For cases to be adjudicated, the law must construct as ‘other’ two subject positions that exist only in relation to each other: victim and perpetrator. One imagined ‘other’, the perpetrator, is fashioned as the subject who executed the violence. The victim, the second imagined ‘other’, is envisioned as the subject to whom violence was done.

The criminal justice system unhinges the act in question from its context. It considers it only in its abstract sense and tries to determine whether the litigants can be positioned in a clear victim–perpetrator relationship. If such a relationship is found, a conviction results (guilty); if not, the defendant is acquitted (not guilty). If it is not possible to determine this relationship, the case is dismissed (through lack of evidence or because the case cannot be concluded without reasonable doubt).

As in the case described above, in court proceedings the courts employ certain tactics that cement these categories of victim and perpetrator further. First, the fact that the accused must face the wall and may not speak does not allow us to imagine them as a person. Second, given that the prerequisite for a conviction is whether the alleged victim is below 18 and whether sex took place, not why and how, the accused is a priori regarded as a possible perpetrator rather than as innocent until proven guilty. Magistrate Binneh stated that ‘with these cases, the law is too rigid, and the presumption is that the moment you are reported then you are guilty’. This is very much in line with the Comaroffs’ reflections that in the postcolony today ‘policing in the name of order frequently makes felons before-the-fact, punishing them prior to their breaches being legally established. Or even committed’ (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2016: preface). A High Court judge explains: ‘The law says: innocent until proven guilty. But with sexual penetration, the second you are accused you are treated as guilty and you remain that unless you can prove that without any doubt you are innocent, and for that you need a good lawyer’. This shows that criminal justice personnel may be as critical of the Act as citizens are. And yet they were part of its creation, even though they now outsource this responsibility to ‘strangers’.

Magistrate Binneh comments:

Anyone can make the report, and once the report is made, you are in big trouble because the human rights organisation, media, and activists are very much interested in such cases. When they are reported to the police, they give them the greatest of attention and they will write and publish about you, so even if you make it out, your image is ruined.

Although the victim does speak, she does not exist independent of the perpetrator and is labelled as a minor and hence unable to consent. What she says can change the severity of the sentence but not whether the act is considered as a form of violence or the dynamics of her or the perpetrator’s positioning. In this regard, she is not heard. It is only others who can unleash her personhood from the subject position of the victim. In his work on female combatants in African wars, Mats Utas warns that ‘by employing a perspective that makes a woman exclusively a victim, researchers risk creating a permanent state of what Kathleen Barry calls victimism ... i.e. a woman’s victim status “creates a framework for others to know her not as a person but as a victim, someone to whom violence is done”’ (Utas Reference Utas2005: 407). In the case of the victim in court, this reductionism is the intended effect. The state cannot know her as a person; it must not become interested in her as a person. Its sole interest lies in establishing whether she is in fact a victim or not in relation to an ‘other’, whose position is dependent on hers.

Critical Voices

While the SOA is internationally celebrated as an important step towards countering sexual violence, its effects have been ambiguous. Research collaborators criticised the SOA for criminalising local norms of sexuality and consent. Mr Samura (73), a former teacher, referring to the campaigning around the SOA, told me:

What they are saying is that when you have sex, you will only think of sex and lose your mind somehow. Then that will lead you to drop in school and to lose attention for what is important. I think what they don’t realise is that they themselves had sex when they were young, and they still built homes. We always say that in the village everyone saw you, so you could not just have sex. But people were also married when they came out from the initiation, so when they were between maybe 13 and 16, and then they had children. How is that different from the girls who have boyfriends in the city when they are in middle school?

It is natural for young people, for any people, to think of sex. Sexing and making new life is what makes us human and what makes us connect, especially for young people. If you forbid it, it will be even more distractive because they will think of it even more and will spend a lot of energy finding ways to do it. It is not about forbidding it but finding ways to do it in a responsible way. These NGOs, they are really not thinking.

In their criticism of how the development discourse has infiltrated sexual education and how sex is depicted as destructive, these statements expose the one-sidedness of this approach. They reveal the limitations of the intention to ban sexual activity, which does not hold up to critical enquiry. They show, too, how a dialectical approach could have led to a far more realistic and successful solution.

The clash lies, among other things, in different interpretations of age: numerical for the state, social for research collaborators. While the law requires numerical certainty, age in Sierra Leone is not understood as a number. It is in exchange with others that one’s position within relational dynamics is determined (Bledsoe Reference Bledsoe1980a; Leach Reference Leach1994; Ferme Reference Ferme2001; Jackson Reference Jackson2017). Depending upon whom one relates to, one can be older, younger, big, or small (Oyěwùmí Reference Oyěwùmí1997; Bakare Yusuf Reference Bakare Yusuf2003). It is as common for men to be kept in the stage of youth until well into their forties as it is for young girls to fall pregnant and marry well below the age of 18. Not one of the 53 men whose stories I heard at Pademba Road Prison knew the age of the girl they allegedly penetrated. It was only at the police station that this number was revealed to them. Consider the explanation of a young man who was convicted: ‘They [the police] asked me for her age. I told them that she is grown up, that she started having sex, that her breasts are developed and that she has given birth to a child. Then they told me she was 15 and I am 19’. Alusine (21), one of the men I interviewed in prison, told me that in accordance with social standards, these men rated the girl’s age in terms of her physical appearance. As soon as a girl starts to develop breasts, she is ‘ripe’ and can be approached for intercourse (Jackson Reference Jackson2017: 42). With the first pregnancy she is a woman, and after breastfeeding, when her breasts begin to ‘fall down’, she ‘has matured’.

The Act remains only marginally effective in protecting very young girls from sexual violence and harassment by much older men. At the same time, it has led to the incarceration of numerous young men and boys. Many research collaborators disapprove of the Act’s execution because a teacher raping a 14-year-old student may receive the same prison sentence as a 19-year-old sleeping with his 17-year-old girlfriend. A lawyer from the Legal Aid Board – an institution established in 2012 to offer free legal representation to those who cannot afford a private lawyer – who represented most of the men I interviewed at Pademba Road Prison, explained: ‘Sometimes I defend a teacher or pastor or neighbour who rapes a small girl or a child, but mostly it is youth. Some are fooling around, you know, some are maybe impregnating someone. Mostly I have boyfriends, lovers, I would say’. A High Court judge states:

We have serious problems with rape in this country. But of 25 or maybe 30 cases I see, few are child cruelty, few are domestic violence, few are rapists, but mostly there are boyfriends here you know, lovers. Maybe almost 23 of them are lovers. But the law is so rigid that I have to convict no matter the circumstance.

Because the main burden of proof is to show that sex has taken place, it is cases involving girlfriends and boyfriends that are more easily convictable. Girlfriends often believe that they can help their accused partners by explaining their relationship in court. They rarely miss court hearings and enable a quick processing of cases. Yet, by confirming that sex took place while they were legally unable to consent, they usually ensure their partner’s conviction. This situation was often described to me as ‘the girlfriend trap’. Magistrate Binneh comments: ‘If she was a minor, if sex took place and if it took place between the litigants, we must convict’. Although people have become aware of this ‘trap’ and have increasingly developed tactics to avoid it (e.g. if girlfriends do not attend court hearings, the case will be dismissed), the law is still very recent. Owing to the Ebola pandemic, during which legal proceedings were often slowed down or interrupted, the Act has only been in operation uninterruptedly since mid-2016 and the SOAA has brought additional changes, the consequences of which are yet to be fully assessed.

Many Sierra Leoneans who were involved in ratifying or executing the SOA and the SB were equally critical of their workings. During one of the cases in chambers between a 19-year-old accused and a 16-year-old alleged victim, a current politician who was the defence lawyer of the accused interrupted the hearing in frustration. After we had listened to both parties stating that they were in a consenting relationship, the defence lawyer exclaimed:

This makes no sense at all. What are we even doing here? There are real rape cases to attend to. In the UK, the age for consent is 16, and they are debating to lower it to 14 even. This is ridiculous. These people want to have sex. You can’t send them to prison for that. Look, this is her boyfriend!

Magistrate Binneh, who presided over the case, replied:

You say that now, but remember when we were making this law, you were one of the first to stand up and tell the commission that this is the best thing to do. Even back then I was against it, I knew that it would be a catastrophe and you would have all these boyfriends which you then need to convict. This is the difference between politicians and the lawyers and judges who deal with the law daily.

The defence lawyer replied with a sigh: ‘Yes. I thought it would get us developed super-fast. No more rape or early marriage, girls in school and focussed on work … but it is a disaster now, and I only know that because I am a lawyer’.

Others blamed the laws on the TRC and on development agencies. Even though they had ratified the law, they claimed that they had done so not on their own account but because they were ‘told to do so’. By regarding themselves as influenced by the ideas of foreigners, they created a narrative of deferred responsibility that allowed them simultaneously to ratify the SOA and criticise it. This erased their culpability and created a position of exceptionalism in which they could carry out the law and yet wash their hands of any responsibility for its consequences. A lawyer and politician who was part of designing the SOA and is now carrying it out, explains:

I think someone out there, some of you white people, were thinking: ‘OK, how do we stop this violence in Sierra Leone?’ ‘OK, we are just telling these Africans to stop having sex’. This is what happens all over Africa. But this is nonsense. You can never stop that. Then you can also send these young girls who have been raped to prison because they had sex. No, sex is not the problem. Violence is the problem. In your country is sex under 18 a crime?

That the foundations of the law are not believed – that it is sex rather than violence that is under consideration – is also evident among criminal justice personnel in chambers. It is very common for those present to tease a witness or laugh at the ways in which she describes acts. Mocking statements by lawyers and others present are common, such as: ‘So here you are to put your man in prison?’ or ‘Oh baby, first you enjoy the sex and then you complain about the consequence’. These claims may be interpreted in two ways. First, they can serve as an extension of the punishment, a form of social punishment, for the alleged victim. Second, they may be a form of everyday resistance (Scott Reference Scott1985), albeit a cruel one, to the law’s attempt to criminalise young people’s sexuality and strip girls of their sexual agency. By being recognised as sexual subjects who tempt men and boys, they are perceived and also criticised as actors with agency rather than as silenced victims.Footnote 13

Another criticism concerns the ineffectiveness of the law in targeting rape. In rape cases or in cases involving children or teenagers who were assaulted by older men, victims often do not report, withdraw their statements, experience pressure to withdraw, do not attend court hearings, or are too young to give testimony (see Medie Reference Medie2013 for Liberia). Thus, their cases tend to take much longer and are often dismissed. Furthermore, older men or the families of wealthier youth continue to be able to reach a ‘friendly settlement’, which is an out-of-court solution. Such people can pressure third parties to abstain from reporting. Rape cases that do not lead to pregnancy are rarely reported to the police because the parties involved find the out-of-court solution preferable. If a report is made, it is usually because the girl in question is extremely young, was gravely injured, or became pregnant. Consider what a teacher told me:

Now with the girl child agendas, you should report such cases to the police. But you yourself are struggling. If you report someone from a rich family to the police, they will come after you and it will be very difficult for you in your school from then onwards. If you just talk to them, there will be some remuneration for you. They will settle the matter otherwise and will reach an agreement, and you will benefit. If the case ever goes to court, they report something like larceny, never rape. Let them settle this case among themselves; otherwise, they will destroy you.

When everyday struggles and social realities are accounted for, this ‘imagined image’ of Sierra Leoneans who report no matter the circumstances collapses. Since it is often poorer and younger men and boys who are accused, the Act becomes yet another powerful reinforcement of the prison system that confines poor city-dwellers and disproportionately punishes the poor (Wacquant Reference Wacquant2001). Moreover, reporting by third parties and bystanders has led many to believe that accusations of sexual violence are made out of vengeance, because of quarrels between families, to punish certain types of young men and to remove them from society.Footnote 14 Many understand the new laws as a Western attempt to make sexual relationships out of wedlock illegal and to regulate fertility. Concurrently, this has made it even more difficult for women and girls who suffer violence to report safely. Moreover, although the SB has since been lifted, its effects continue to linger and the stigma surrounding teenage pregnancy makes attending school difficult.

This chapter has hopefully shown the strengths of detailed ethnographic work. In situations where the intentions of policy-makers to protect certain groups from violence differ substantially from the ways in which these targeted populations experience them, ethnography becomes practically relevant for law and policy. It uncovers the social world in which laws passed to combat violence and ‘advance’ gender justice take root. It demonstrates how people react to and feel about them, and how this in turn influences the application and impact of such laws. An ethnography that examines the interaction between law and lived experience can show the potential gaps between the intention of laws, their implementation, and their impact. When development experts and policy-makers try to promote safety, security, and justice through laws without careful consideration of the context in which they are passed and implemented, their effects may end up hindering instead of furthering the goals desired. Including the testimony of affected people as well as the insights of scholars can help avoid well-meant laws and interventions like the SOA(A) to produce adverse consequences.