[O]rthodox historians would limit themselves to telling only “what really happened” on the basis of what could be justified by appeal to the (official) “historical record”. They would deal in proper language and tell proper stories about the proper actions of proper persons in the past, Thus, insofar as history would be called a science, it was a discipline of “propriety.”

White’s claim that history was a discipline of propriety is particularly apt in the context of nationalist historiography that often seeks to produce a historical orthodoxy, which laid out a proper record of the community’s past.Footnote 2 This chapter is about the creation and impact of an Odia historical orthodoxy. If the first three decades of the twentieth century saw the articulation of an Odia selfhood that came to be increasingly divorced from exclusive definitions of linguistic identity and came to be associated with a more inclusive idea of belonging to a common land then the 1930s saw a concerted effort to produce a historical record of this common land and its inhabitants. However, the need to create a “proper” narrative of Odia past meant that the emerging historiography of the Odisha had to deliberately render invisible a sizable minority of the province: the adivasi communities.

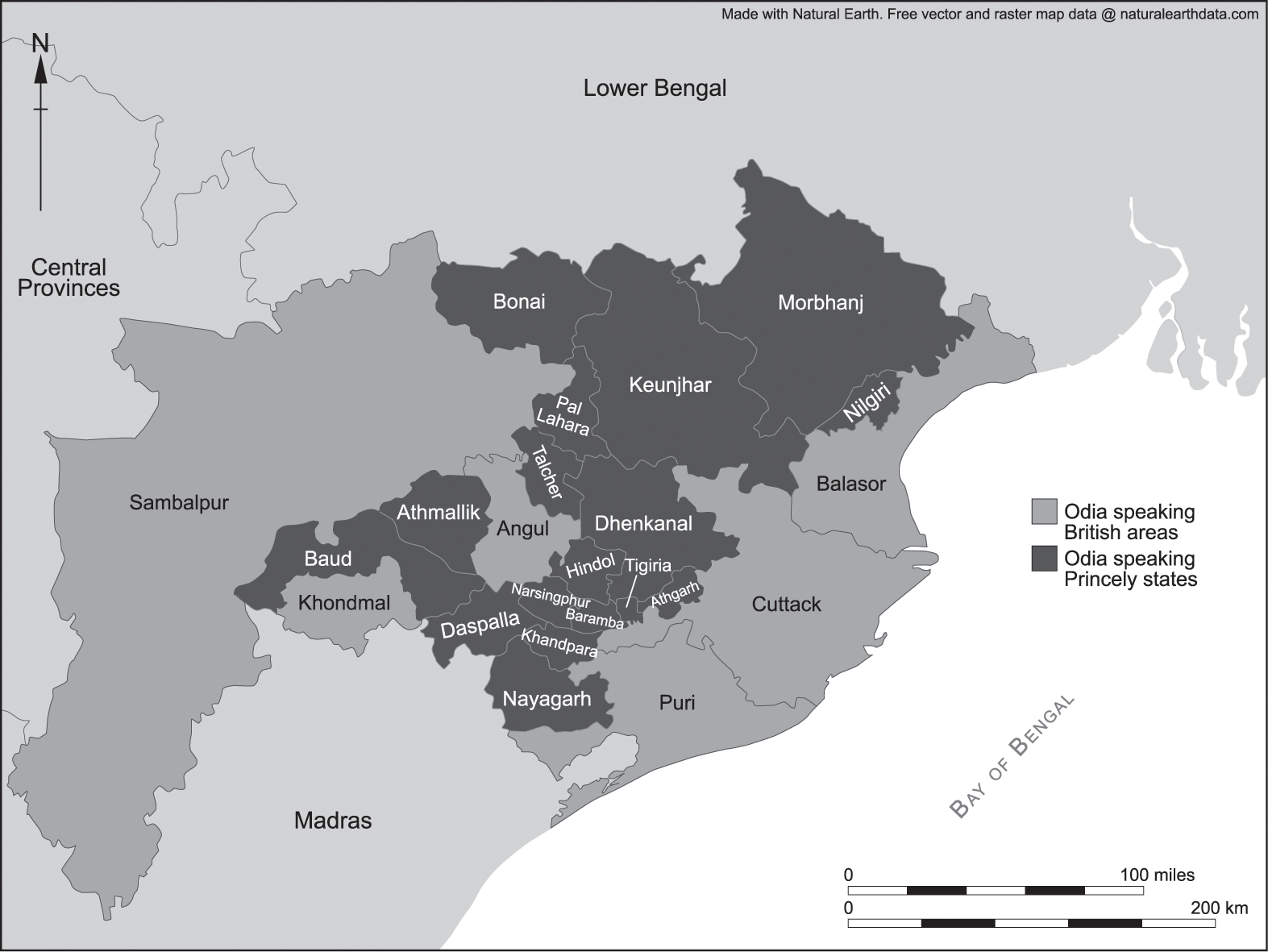

As the notion of linguistic provinces gained support from both the colonial state and the leadership of the Indian National Congress, the idea of a linguistic region of Odisha had to be coupled with concrete definition of and justification for an Odia regional space. We have seen in Chapter 3 that, by the mid-1920s, talk of regional boundaries that would divide existing provinces such as Bihar and Odisha, the Bengal Presidency, and the Madras Presidency into new linguistic provinces had already begun to appear in government deliberations. The Phillip Duff Committee, setup in 1924, was tasked with clarifying the linguistic nature of the Ganjam district of the Madras Presidency and exploring the possible inclusion of this district in the future province of Odisha. As the newspaper coverage of the committee suggests, the Odia political leadership had become increasingly entangled in discussions about the affinity of communities occupying the border regions and the majority populations of the proposed province of Odisha.

By the 1930s, this need to clarify the linguistic nature of the inhabitants of border zones had become crucial because of the institution of the Orissa Boundary Commission. Tasked with the job of drawing the boundaries of the new province, the commission received memoranda from a variety of associations and communities about whether the inhabitants of border districts like the Ganjam district were Odia or Telegu. The need to claim territory as an “Odia-speaking area” became one of the more urgent impulses in Odia historiography of the 1930s. However, this raised a fundamental contradiction. To write a history of Odisha was to write a history of Odia. And as we saw in Chapter 1, the effort to establish linguistic singularity of the language posed the fraught question of the adivasi. To recap, late nineteenth-century Odia intellectuals claimed that Odia was different from Bengali because of the intermingling of the regional prakrit with the indigenous adivasi languages prevalent in ancient Odisha. The adivasi formed an uncomfortable element in the narrative of Odia origins. In what follows, I will show why the figure of the adivasi was such a fraught presence in the Odia past and present and how efforts were made to incorporate them into the regional community by rendering them into an invisible minority. This chapter illustrates how the adivasi as a historiographical problem was resolved in both histories of Odisha written in the early twentieth century and the regional movement for the formation of the province of Odisha.

The Adivasi Conundrum

For early twentieth-century Odia historians, the adivasi presence in the Odia-speaking areas posed a historiographical problem. The need to counter W. W. Hunter’s aspersion that the ancient Odias lacked historical achievement required a progressive historical narrative of the Odia past that presented the present-day Odias as most modern editions of a historically illustrious people. However, historians of Odisha were faced with a dilemma. On the one hand, the contemporaneous presence of the “primeval tribal” in the early twentieth century threatened to disrupt this new Odia historicism. On the other hand, it was essential for Odia historians to incorporate the adivasi into both the past and present of the Odia community, even as their presence put in question the emergent Odia claims to a higher civilizational status based on an illustrious historical tradition. This was because the movement for the formation of a new province of Odisha through the amalgamation of the Odia-speaking areas required histories that not only illustrated to the colonial government a shared historical past for all such areas but also made a case for the incorporation of the adivasi population (non-Odia speakers) of these areas into the Odia community. Therefore, Odia historians of the early twentieth century were challenged with a three-pronged task: the need for a history that established Odia civilizational and historical bona fides that conclusively proved that the Odia-speaking areas belonged to a single historical past and that incorporated both the mainstream Odia population and the non-Odia adivasi population into a single historical community. This project, both cultural and geographical, faced its greatest challenge in the figure of the adivasi. As she/he was considered neither historically civilized nor linguistically Odia, the adivasi became a sticking point in the histories of Odisha written in the early twentieth century.

In the areas that the Odias claimed as part of the proposed province of Odisha, the adivasi population was sizable. Just the northern and southern part of the proposed province, excluding the western area, contained 230,7144 adivasis of various communities such as Khondh, Savara, Godaba, Poroja, Munda, Oraon, Kharia, Hos, and Bhumij.Footnote 3 This was roughly a fourth of the total population of the areas being claimed as Odisha. Most of these communities were not primarily Odia speaking or Hindu. In fact, quite a few of the adivasis communities spoke their own languages and the tribes were named after the language they spoke.Footnote 4

Theoretically, this problem of the adivasi could have been resolved by what Johannes Fabian calls the “denial of coevalness,” where the adivasi is simply seen as an anachronistic presence who could be dismissed as an exception.Footnote 5 Such a case has already been made in the Indian context. In her insightful treatment of adivasi pasts in Bengal, Prathama Banerjee argues that Bengali modernity was “centrally defined by the dominance of the historical.”Footnote 6 She suggests that the production and sustenance of this modernity required the marking out of a “primitive” within the community. The Santhals of Bengali came to serve as this “primitive within.” The Odia case is slightly different. The Odia primitive is much more intimate than the Santhal is. Therefore, in Odia historiography the adivasi could not be so easily dismissed. The adivasi population played a peculiar role in the constitution of the proposed province of Odisha. The demand for a separate province of Odisha required historical proof of the incorporation of areas where a majority of the population was adivasi. Hence, rather than viewing them as inconsequential temporal exceptions, the Odia historians of this period had to provide a theory that would explain the relationship between the mainstream Odia-speaking population and the adivasi population. Yet this relationship could not undermine the existing hierarchies within Odia society. Therefore, the Odia elite anxiety about the adivasi was based on a paradox. While Odisha as geographical category could not be imagined without incorporating the adivasi into the Odia community, the imagination of the Odia community could not include the adivasi due to his perceived historical backwardness.

The question of the adivasi was not simply an academic conundrum. In this period, history writing was important to anyone involved in the Odia regional political project – the amalgamation of all Odia-speaking tracts under a single administration. Essential to this project was a justificatory historical narrative that produced the “place” Odisha as a long-standing historical and geographical entity. This was especially challenging because a historical Odisha that would be contiguous with the boundaries of the desired province of Odisha had never existed in ancient times. Natural Odisha, as the projected province came to be called, had been four different kingdoms in the ancient times – Kalinga, Utkala, Odra, and Kosala. Present-day historians of ancient Odisha have gleaned from ancient sources like the Mahabharata and the Manusamhita that “these areas were inhabited by the [sic] different stocks of people, but in the course of time they gradually became amalgamated, though the distinct nomenclatures of their territories continued to exist.”Footnote 7 The modern name Odisha is a tenth-century AD bastardization of the name Odra and its other derivatives such as Udra and Odraka. A geopolitical Odisha akin to the projected “Natural Odisha” came to be established only in the eleventh century AD under the Imperial Ganga Dynasty that ruled Odisha for almost three and a half centuries.

It could be argued that the case for natural Odisha could have been made by referencing the historical Odisha of the Ganga Dynasty. However, the discursive privileging of ancient Indian history as the justificatory marker for early twentieth-century political demands made it essential for the proponents of a separate province of Odisha to prove that Odisha was an ancient geopolitical entity.Footnote 8 Hence, in this period the production of an ancient historical Odisha became one of the more significant projects of Odia regional politics. The effort was to ensure that the emergent histories of ancient Odisha established that the four kingdoms of Kalinga, Utkala, Odra, and Kosala were integrally tied together by cultural and political bonds. Furthermore, the Odia nationalist historians were invested in proving that these kingdoms were inhabited by both the original aboriginal inhabitants of the areas (understood as the ancestors of the adivasis) and the “civilized” Aryan immigrants from northern India.

While Odia historians were engaged in an effort to produce a unified, ancient, cultural, political, and linguistic heritage for the Odia people, the particular political ends served by these narratives defined the limits of what was acceptable as a story of the Odia past. Not just any narrative would do. Odia history writing in this period was a site where the very nature of the modern Odia linguistic community was being produced. The Odia elite’s anxiety about incorporating a sizable number of “aboriginal” adivasi groups of the Odia-speaking areas into the Odia community was resolved through specific iterations of origin myths linked with the Odia linguistic community. These myths centered on the Jaganath cult. By implicating both the adivasi people and the Odia-speaking people in a legendary narrative, these legends of the cult of Jaganath served as a bridge between these two groups. Through a reading of the historiographical use of these origin myths, this chapter traces the actual political stakes in producing narratives of the Odia past that would both establish the unity of the adivasi and non-adivasi elements of Odia society and maintain existing social hierarchies between the two groups.

Early History Writing in Odisha and the Need for a Patriotic History of Odisha

Early histories of Odisha were written by colonial officials in the nineteenth century. These colonial histories of the Odia speaking tracts, like histories of other regions in early colonial India, were written as guides for colonial administrators. History writing was a colonial exercise in as much as it produced useful colonial knowledge as it created a particular reality for the colonized people. Bernard Cohn points to the ontological power of history written by colonial officials in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The ontological power of these histories resided in the effects of the knowledge produced on the actual administration of Indian provinces. Cohn argued here that the study of Indian history allowed the Colonial officials to apprehend Indian customs and traditions. This in turn enabled them to effectively rule and administer India.Footnote 9 On the other hand by producing and perpetuating colonial knowledge these histories ossified particular interpretations of Indian society and its past. In so doing they produced a new self-image of the subjects they were seeking to represent.Footnote 10

Similarly, colonial histories of Odisha outlined the nature, of the land, people and culture of the region. These histories were necessarily essentializing and produced a distilled vision of the colonial apprehension of the native Odia. We saw in Chapter 4 that W.W. Hunter described Odisha as a primitive land of no historical glory. Hunter’s history serves as an instance of the colonial portrayal of Odisha that provoked the twentieth century native re-elaboration of the Odia past.Footnote 11

Hunter’s reading of the history of Odisha was representative of the Orientalist essentialization of the non-Western life. Anouar Abdel-Malek has argued that this effort to essentialize the Orient reads it as both historical and ahistorical.Footnote 12 Hence, the essentialization inherent in Orientalist scholarship involved the production of two parallel readings of the object of study: first, a reading that establishes the object’s changeless historical essence and, second, a reading that underlines this changelessness by posing it in a historical narrative where everything but the essence changes.

In Hunter’s history of Odisha, this dual reading appears in two parallel histories of Odisha: one, the unprepossessing history of the upper-caste Odia population and, two, the history of the primeval adivasi population caught in an equally primeval landscape. Here, the unchanging adivasi and his inability to tame the Odia landscape serve as the essence of Odisha even as Hunter clearly does not equate the adivasi with the rest of Odia’s population. Hence, despite the absence of any apparent arguments about the linkages between the upper-caste Odias and the adivasis, Hunter attempted to substantiate his reading of ancient Odisha as a singularly uneventful place with the example of the primevalness of the adivasi.

Even though we have discussed Hunter in the previous chapter, his description of adivasis in Odisha bears further attention. In the body of his book, while Hunter foregrounded the lack of civilization and advancement in his contemporary Odisha, he traced the ancestry of modern Odias to pre-Aryan “aboriginal people.” He argued that the earliest inhabitants of Odisha were “hill tribes and fishing settlements belonging to non-Aryan stock.”Footnote 13 He saw the modern-day Savara and Khonds as the descendants of these “aboriginal inhabitants” of ancient Odisha. Hunter quotes ancient texts to illustrate the disdainful attitude of the Aryan Sanskrit writers towards these tribes. In such texts, they had been described as cannibalistic people who were a “dwarfish race, with flat noses and a skin the color of charred stake.”Footnote 14 However, Hunter argues that these hill tribes were not the only inhabitants of ancient Odisha. They coexisted with other communities “belonging to another stock and representing a very different stage of civilization.”Footnote 15

Hunter’s acknowledgement of the presence of diverse “races” in Odisha coupled with this narrative privileging of the adivasi section of the population enabled him to essentialize Odisha as a land of primeval unhappening. This portrayal of Odisha, particularly the marginalization of the “Aryan” element of the Odia population would potentially undermine later Odia efforts to claim a higher civilizational status through an Aryan kinship with their European masters.Footnote 16

It is against this backdrop that the search for a more flattering history of Odisha took place. Various writers as early as 1907 drew attention to the need for a history of Odisha written by Odias themselves. Odia leaders argued that colonial and Bengali historians had failed to write an adequate history of Odisha that would foreground the cultural heritage of the ancient ancestors of the Odia people. For instance, in 1917, in his article “Prachin Utkal,” Jagabandhu Singha critiqued histories written by Hunter and some unnamed Bengali scholars and argued that: “In these times those who can advertise their accomplishments emerge victorious. Those, who remain silent have their ancient heritage appropriated by others.”Footnote 17

Here, Singha made a veiled reference to the prevailing apprehension among the Odia elite that the Bengalis and the Telegus were attempting to appropriate elements of the Odia historical past. For instance, Singha devoted an entire chapter in his book Prachin Utkal to prove that Jayadev, the renowned author of Geeta Govinda, was Odia and the text was originally written in Odia.Footnote 18 In this chapter, he refuted the contentions of a number of Bengali writers who had claimed Jayadev as a Bengali figure.Footnote 19 Thus, in this period, history writing was a site of cultural contestation between various regions in India. Claims about a glorious historical tradition were not only a response to colonial official narratives about the primitiveness of Odias but also an engagement with neighboring communities like the Bengalis and the Telegus in order to lay stake on the past. This perception of the usurpation of Odia past contributed to the creation of defensive historiography that strove to reclaim the aspects of the Odia past that had generally been ascribed to other regions.

Essays on history published in the Utkal Sahitya reveal that throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, Odia intellectuals were making an effort to define clearly the project of history writing. Their primary preoccupation was the introduction of a “Western” concept of history into Odia discussions of the past. Therefore, many such essays began with clarifications about the meaning of the term itihasa or history. Contrary to claims by historians that colonial histories written by Indians were driven by traditional Indian understandings of itihasa, these essays explicitly modeled their discussions on a Western understanding of historical writing based on evidence, observation, and a rational search for a past reality.

For instance, in the essay titled “Itihasa,” written in 1906 by Chandramohan Rana, the author proposed a new understanding of the traditional term itihasa. He argued that, although the term came from a Sanskrit root, its meaning had changed. Rana claimed that, in its new sense, history meant “a description of some person, community or country informed by its function, origin/cause and future/consequences.”Footnote 20 Such an articulation of the understanding of history based on functions and consequences reveals the emergence of a functional attitude towards history writing in the early twentieth century.

Interestingly, Rana made no effort to explain the original meaning of itihasa. It appears that the essayist’s primary concern was to make a case for the new itihasa. For Rana, the new itihasa was to be modeled after histories written by major classical Western historians like Herodotus. Even as Rana conceded that the histories of Herodotus contained a liberal sprinkling of fiction, he insisted that these histories were the urtexts of a new kind of history writing. Rana pointed out that as such histories did not exist in Odisha. Hence, the task before the intellectuals in Odisha was to write new histories of Odisha modeled on those of the West.

Intellectuals such as Rana applied themselves to the explication of the process of writing such histories. Fundamental to this process was the identification of dependable sources that would serve as evidence. In an article titled “Itihasara Krama” (The Course of History) by Jogesh Chandra Rai, read at the April 1915 Session of the Utkal Sahitya Samaj, the question of historical evidence was raised. Rai called for a concerted effort within the Utkal Sahitya Samaj to collect historical source material on the history of Odisha. He lists five important categories of texts: Madalapanji Temple records of the Jaganath Temple at Puri, genealogical histories collected by the rulers of the princely states, village records preserved in palm leaf manuscripts, minor temple records, and copper plate inscriptions. In spite of this call for attention to such a wide variety of sources, new historians of the early twentieth century depended heavily on the Jaganath Temple record – the Madalapanji papers. Consequently, products of such research remained deeply mired in the narrative strategies and evidentiary information provided in the temple records. The result was a deeply Hindu, upper-caste telling of the history of Odisha.Footnote 21

As a result of such discussions about the need to write a new, more scientific history of Odisha, the Prachi Samiti was formed in 1930. Also, a history wing of the Utkal Sahitya Samaj, exclusively devoted to the investigation of the history of Odisha, had been set up in 1915. Most histories written in this period were fostered in these two forums of historical writing.

Even though these two groups covered a variety of historical topics, they were both informed by a common discursive interest in the historical construction of the Odia community. Within the historical construction of the Odia community, there were two main concerns. First among them was the need to create a historical geography of Odisha that would incorporate all the areas being claimed as part of the proposed province of Odisha. Second, historians needed to counter claims like Hunter’s primeval description of Odisha by establishing a glorious historical past for Odisha. This project of writing a glorious past for Odisha was threatened by the presence of the “uncivilized” adivasi in the imagined community of Odisha. Hence, historians of this period had to perform a dual task of proving that Odisha was a product of an ancient civilization while accounting for the adivasi presence within the Odia community without undermining their project of giving Odisha a glorious past. For this reason, the figure of the adivasi became one of the most enduring preoccupations in the history writing in Odisha. The rest of the chapter investigates the implications of this anxiety for regional politics in Odisha.

Anxious Origins: Majumdar’s Odisha in the Making and the Problem of the Adivasi Origin of the Modern Odia Community

Odia anxiety about the adivasi reached a flashpoint in 1926 when B. C. Majumdar wrote that not only were there adivasis in ancient Odisha, they were also the ancestors of modern-day Odia people—even those who claimed Aryan heritage. Majumdar, a professor at Calcutta University, argued in his book Odisha in the Making that “the history of Odisha begins where the history of Kalinga Empire ends.” An established and well-regarded scholar of Odia history and literature, Majumdar was tracing the process by which a unified linguistic Odia community came into being. The cornerstone of his argument was that the ancestors of modern-day Odias had no links with the Kalinga Empire and, in fact, came to be identified as Odias as a consequence of the processes set in motion by the fall of the empire.

To illustrate the significance of Majumdar’s claim about Odisha and Kalinga, I should introduce the Kalinga Empire. References to the Kalinga Empire abound in ancient Hindu scripture. These texts refer to a very powerful, cultured and prosperous kingdom covering an area roughly contiguous with the proposed province of natural Odisha. By claiming descent from the Kalinga Empire, Odia historians of the period could claim a glorious historical heritage that had been denied to them by historians such as Hunter.

Majumdar’s claim and the unfavorable response it provoked among contemporary Odia historians reveals the significance of history writing in early twentieth-century Odia political life. For example, Odia nationalist historians such as Jagabandhu Singh posited alternative linguistic and racial pedigrees for the Odia-speaking people. Singh argued that ancient Odisha, commonly called ancient Utkal, had always been linked with the Kalinga and the two names Utkal and Kalinga were often used interchangeably in the past. Sinha took particular offence at Majumdar’s claim that the ancestors of modern-day Odias were aboriginal, “uncivilized” Odra and Utkala races who were later Aryanized by people of Aryan stock and rendered itinerant due to the fall of the Kalinga Empire. Countering Majumdar’s depiction of the origins of the Odia language and people, Sinha argued that the Odra and Utkalas were of Aryan descent. The points of contention in these two narratives of the Odia past hinged on the question of the provenance of the Odia language and, by extension, of the modern Odia people.

By the time Majumdar’s Odisha in the Making was published in 1926, he was a well-known academic figure in Odisha. A professor at Calcutta University, Majumdar had published many influential texts on Odia literature. Most notably his three-volume Selections from Odia literature was a prescribed textbook for undergraduates in the Odia department of Calcutta University. Odisha in the Making was also designed as a scholarly text and, to this end, Majumdar prefaced his book by clarifying that it was “intended to constitute rather a sourcebook than a story of Odisha for popular readers.”Footnote 22 The book was commissioned by Calcutta University but, due to its paucity of funds, it was finally funded by the Raja of Sonepur, an Odia-speaking princely state.

In this section, I argue that early twentieth-century histories of Odisha had much more than the delineation of an ancient place named Odisha at stake. As the disagreement between Majumdar and Odia nationalist historians such as Singh reveal, it is the question of the racial and linguistic pedigree of the modern-day Odias that is the central matter of contention. While both agree that the modern-day Odias are descendants of the inhabitants of Odra, Utkala, and Kosala, Majumdar’s effort to delink the connection between ancient Kalinga and the history of modern Odisha raised an objection from Singh. Majumdar’s claim was based on the argument that the ancestors of the modern-day Odias were, in fact, aboriginal tribes who were “civilized” by the invading Aryans and this history did not intersect with the history of the Kalinga Empire. Singh’s discomfort with this claim, which established an aboriginal heritage for the modern Odia people, is revealing.

Majumdar’s primary object was to investigate:

How and when several tracts of dissimilar ethnic character did come in to the composition of Odisha as it now stands by accepting an Aryan vernacular as the dominating speech for the whole province.Footnote 23

Thus, his text described the process by which a historical Odisha came into being. He hoped to correct what he considered was a prevalent misconception about the historical antecedents of Odisha. He argued that, in writing the history of Odisha, historians should take into account the history of not merely the coastal tract of Odisha. Rather they should investigate how the hilly tracts of Odisha came to be linked in with the province of Odisha. He was seeking to do a holistic history of Odisha. Majumdar held that this exclusive emphasis on the history of the coastal Odisha, particularly Puri, was misleading. This was because rather than the whole of modern Odisha only the coastal tract was part of the ancient Kalinga Empire. Scholars had mistakenly associated Utkala or modern Odisha with the ancient Kalinga Empire. As a corrective measure, Majumdar argued that historians of Odisha should look at the history of the hilly tracts and not coastal areas of modern-day Odisha to trace the history of the land.

He focused on how racially disparate non-Aryan tribes named Odras and Utkalas came to constitute a linguistically homogenous group – the Odia-speaking people. Majumdar argued that the ancient kingdoms of Kalinga, Utkal, and Odra were three distinct but contemporary political entities before the fall of the Kalinga Empire in the seventh century BC. He quoted ancient texts such as the Mahabharata to prove that Kalinga was a mighty empire that stretched from the river Ganga in the north to the river Godavari in the south. A highly cultured and economically prosperous empire, Kalinga had actually been mentioned in the Mahabharata as racially akin to the Aryan Angas and Vangas. In contrast, the Utkala people are mentioned in his sources as “rude people of very early origin having no affinity with the races around them.” They controlled a thin strip of land that ran contiguous to that of the Kalinga Empire. Similarly, the Odra people populated the northwestern part of present-day Odisha. Majumdar quotes extensively from Huen Tsang’s travel accounts to prove that the general disorder and chaos that ensued after the fall of the Kalinga Empire in the seventh century BC was instrumental in the creation of Odisha. It is during this period of transition that the “rude tribes” of the Odras and the Utkalas “poured” into the coastal tract of the erstwhile Kalinga Empire. As this coastal tract was one of the primary centers of Hindu religion, contact with the religious institutions, resulted in the gradual Hinduization of the Odras and the Utkalas to produce the ancestors of present- day Odia people. The name Odisha therefore draws from the word Odra. And Utkal, the classical name for Odisha, draws from the Utkala, another ancient aboriginal people.

Majumdar’s argument had two important implications for the study of history. First, by claiming that only the coastal tract of Puri was part of the Kalinga Empire and the Kalinga Empire was controlled by the ancestors of the Andhra people, Majumdar questioned the Odia nationalist effort to claim lineage from the Kalinga Empire. Furthermore, if Puri, the seat of the religious deity of Jaganath, were part of the empire controlled by the Andhra people, then the Odias could not lay claim to the Jaganath cult as a national cultural unifier. Second, the argument that the modern-day Odias, including the Odia upper-caste elite, are descended from the Hinduised aboriginal tribes of the Odras and the Utkalas threatened to muddle the differentiation between the caste known as the Odias and the “adivasis” of the hilly tracts of Odisha.

Recuperating Odra-Rastra: Legend, History and Incorporation of Adivasi Heritage

Odia nationalist response to Majumdar’s thesis was focused on disproving his claim that the Odras and the Utkalas were uncivilized races who had no links with the Kalinga Empire. The Odia effort to establish the antiquity of Odia civilization was not merely a product of the response to Majumdar. Odia historians were countering Majumdar’s claim as much as they were responding to Hunter’s assertion that Odisha was a primeval land untouched by human endeavor. In the case of Utkala, the task was easy because of the Sanskrit roots of the very term “Utkala.” Utkala was read as the conjunction of “ut” and “kala.” This translated as “high art.” That is, Utkala was the land of high art or high culture. In the case of “Odra,” the task was not as easy, even as proving that Odra was the name of a civilized kingdom was crucial. This was because Odisha was drawn from “Odra Desa” or “Odra Rastra.” Jagabandhu Singh mentioned in an article that the Bengali Vishwakosha defined the Odra as people who were weight bearers. In fact, there were many different iterations of the term Odra in this period. Such references to menial origins of the Odias forced the Odia elite to systematically recuperate Odra from its contemporary definitions in existing historiography.

Here, I will focus on an article written by Satya Nararyan Rajguru, a nationalist historian associated with the Prachi Samiti, titled “The Odras and their Predominancy,”Footnote 24 Rajguru was one of the founding members of the Prachi Samiti. Set up in 1931, the Prachi Samiti was intended to throw “light on the hitherto shrouded aspects of the great Kalinga civilization, which carried the arms of its cultural conquest far and wide, and made the ‘Greater Utkal’.”Footnote 25 The founders believed that the ancient glory of Utkal was lost and with it was also lost the prosperity and pride of the people of Utkal. History was to provide an uplifting memory of a glorious past that would rouse the people of Utkal from the depths of degeneration and powerlessness.Footnote 26 To this end, the Prachi Samiti was striving to bring about a revival of the Odia past through historical writings and republication of ancient Odia texts.Footnote 27

Rajguru’s essay was part of this mission to revive a glorious memory of ancient Odisha. In this essay, Rajguru attempted to advance an alternative narrative of the formation of Odisha, one that was based on the redefinition of the term Odra. He affirmed the prevalent understanding among Odia nationalists that modern-day natural Odisha covers the territories of the erstwhile Kalinga, Odra, and Utkala kingdoms. However, in contrast to Majumdar’s thesis that Odisha was formed when the fall of the Kalinga Empire resulted in the Aryanization of the uncivilized Odra and Utkala peoples, Rajguru argued that the Odra people were the first Aryans to come in from the north. Hence, he argued, present-day Odisha is the result of the intermingling of these Odras with preexisting aboriginal peoples of the land and the gradual spread of Odra influence over natural Odisha.

In Rajguru’s thesis, the Odras were the fallen Kshatriyas mentioned in the Manu Samhita. He noted that some scholars have interpreted the term Odra as “one who flies.” Thus, Rajguru argued that: “The word Odra as interpreted by some scholars is a synonym of a person who flies. Probably this is the first race to fly from the ‘Aryavartta’ or the northern part of India and settle in the south.”Footnote 28 This reading allowed Rajguru to establish the Aryan heritage of the Odra people. As opposed to Majumdar’s claim that the Odras were rude, uncivilized people who inhabited the fringes of the civilized Kalinga Empire, Rajaguru cited ancient texts, such as the Manusamhita and Bisnuparva, to claim that the Odras were a race of people with a separate spoken language Odra-Bibhasa. This language was broadly derived from Prakrit and Pali and later came to be known as Odia. The region in which it was spoken came to be called Odisa or, as the British called it, Orissa. The later influx of the Aryan Utkala people resulted in the Sanskritization of the Odia people.

While Rajguru established the Aryan heritage of the Odra and the Utkala people, he also attempted to establish the linkages between the adivasi population of natural Odisha and the Odra people. He focused on two tribes in particular, the Khonds and the Savaras.Footnote 29 He argued that both of these tribes were the products of the intermingling of the Odra people with the aboriginal people of Odisha. As proof of this, Rajguru took recourse to linguistic analysis of the adivasi languages such as Santhali and Ho. He illustrated the similarities between words in Odia and these languages to prove that languages like Ho are merely local dialects of Odia. This allowed Rajguru to claim that the tribes such as Santhals, Parajas, Hos, Bhils, etc. are part of the Odia-speaking community and that areas inhabited by them should be included in the amalgamated Odisha.

While linguistic similarities established the membership of the adivasis in the Odia community, the relationship between adivasis and the Odras had to be clarified. As has been discussed earlier, in existing historiography, the Odras themselves were portrayed as the aboriginal ancestors of the modern-day adivasis of Odisha. This coupled with the claim that the Odras were also the ancestors of the modern-day Odia elite who were the product of the Aryanization of the Odras and implied not only that the modern-day adivasis and the Odras are racially linked but also that the modern-day Odia caste elite and adivasis come from the same racial stock.

In order to maintain a clear distinction between the Odia caste elite and the adivasis of the hilly regions of Odisha, Rajguru turned to the originary myth of the Jaganath cult. As Jaganath was considered the most important deity of the Odia people, connecting adivasis to Jaganath legitimized their incorporation into the Odia community. In this myth found in the Madala Panji Temple records, the original devotee of Jaganath was a Savara man named Basu. Indradyumna, a kshatriya king of Malava, sent Vidyapati, a Brahmin priest to bring Basu’s idol of the deity to his kingdom. Vidyapati visited Basu and married his daughter. In the course of time, Vidyapati was able to bring the deity to Indradyumna’s kingdom. Rajguru argued that the offspring of the Brahmin and Savara Basu’s daughter are the ancestors of the present-day Savara. The legend goes that, in recognition of Basu and his daughter’s devotion to Jaganath, Jaganath himself decreed that the children of Basu’s daughter be recognized as suddho Savara or pure Savara.

The use of the legend allowed Rajguru to make two claims. First, the Savaras were culturally integrated into the Hindu caste system and belonged to the Odia community. Rajguru noted that it is these suddho Savaras who functioned as cooks in the Temple of Jaganath. As any service in the temple was considered a marker of the great devotion and had immense pacificatory powers, the Savaras were assimilated into the mainstream Odia community. Interestingly, while the essay began with a reference to Khonds and Savaras, there was no discussion of the assimilation of Khonds into the Odia community towards the end of the essay. In fact, by the end of the essay, the Savaras had come to stand in for all the adivasis of Odisha. This shift, coupled with the use of the Madala Panji legend, allowed Rajguru to make a case for the cultural assimilation of the Odia adivasis into the mainstream Odia caste community.

Second, although the Savaras are adivasis, they are a fairly evolved race of people. To this end, he described the Savara system of administration and claimed that even that colonial state deferred to their code. Furthermore, the use of the legend allowed him to conclude that the “Savaras and the Odras were living side by side in Odisha.” This emphasis on the “side-by-side” coexistence is very revealing. Even as the essay seems to be straining against claims about the common origins of the Odia-speaking elite and the adivasis, it is driven by the need to establish that both of them belong to the same community. The use of the expression “side-by-side” enabled Rajguru to claim that the Adivasis of Odisha and the caste Odias belong to the same community without having to accede to any racial commonalities. A common adjacency over a long period of time coupled with a common language was to Rajguru an adequate ground for community.

However, even as he emphasized the cultural advances of the adivasi elements in the Odia population, the use of the myth enabled him to maintain the hierarchies within modern Odia society. The legend of Jaganath implied that while the adivasis were assimilated into Aryanised Hindu Odia society, the terms of their coexistence was based on a clear distinction between the adivasis and the caste Hindu Odia elite.

Naturalizing Adivasi Odisha: Memoranda to the Odisha Boundary Committee and the “Aboriginal Problem”

These efforts to produce a normative Odia past in which the ancestors of aboriginal tribes and caste Hindus of the Odia-speaking areas lived “side by side” had more than just Odia community pride at stake. The production of these histories was informed by the ongoing discussions within the colonial government to inscribe the limits of the proposed province of Odisha. By 1924, the colonial government had decided to act upon the recommendations of the Montague-Chelmsford Report of 1918–1919 that argued for the reorganization of the British provinces in India on linguistic lines. To that end, the government had instituted the Phillip-Duff Committee to investigate the possibility of the transfer of the Ganjam district from the Madras Presidency to the new Odisha province. Similar efforts on a smaller scale were in process in other Odia-speaking areas located in other provinces. This atmosphere of the administrative reform of the political geography of British India was the context for efforts by historians such as Satyanarayan Rajguru in Odisha to construct a unified and glorious past for all the Odia-speaking areas scattered in various British provinces. Such histories produced an Odia historiographical orthodoxy that was put in service of the movement for the creation of a separate province of Odisha.

In 1931, the Odisha Boundary Commission was set up to define the boundaries of the proposed province. The commission received a number of memoranda that made the case for the inclusion of various outlying areas in the province. The language of these memoranda, drafted by leading advocates for the formation of a separate province of Odisha, reveals the stakes of history writing in Odisha during this period. History was the means of producing a historical, “long-standing” regional culture that would inform the colonial production of a new geographical and administrative region in India. These histories were creating a concrete geographical region by arguing that in the past Odisha and its people were part of a common experience. Such claims to common history enabled the Odia elite to demonstrate that the Odia people met the basic criteria that the colonial state has set for an ideal provincial area.

The memoranda noted that the Indian Statutory Commission of 1930 had described these criteria as “(common) language, race, religion, economic interest, geographical contiguity.”Footnote 30 These criteria, particularly those of common language, race and religion, could be proved only through claims about a shared historical past that was based on a common development of language, race, and religion. As I illustrated in Chapter 1, colonial understanding of the development of language and race was entwined in the study of the origins of Indian languages. Hence to prove that a people shared the same language necessarily involved narratives of origin that established the commonality of race. In the case of Odisha, the effort to prove that all inhabitants of the Odia-speaking areas belonged to the same community involved more complicated discursive strategies. Owing to the discomfort with claims to common racial and linguistic origins among the “non-Aryan” adivasis population of the Odia-speaking areas and the “Aryan” upper-caste Odia elite, historians such as Satya Narayan Rajguru drew on religious myths from the Jaganath cult to establish a different kind of commonality. However, this different commonality also had to be rooted in the past. This motivated the construction of histories such as Rajguru’s treatment of the history of Odradesa.

Rajguru’s argument reveals the incredibly productive nature of the Odia historiographical efforts to imagine the Odia community as one comprised of both the Aryan and non-Aryans elements of the population of the Odia-speaking areas. Even as his argument produced a community based on a shared everyday life, his use of the Jaganath origin myth is also indicative of how and why the Jaganath cult became the normative religion of modern Odisha. Thus, historians such as Rajguru and Jagabandhu Singh made the case for a common Odia culture through histories based on the fundamental unity of experience that belied racial difference. Such a reading of the past also enabled Odia claims to areas inhabited by aboriginal populations that interspersed areas where a majority spoke the Odia language. This was especially crucial because the Odia claims to these areas were threatened by the fact that the aboriginal peoples of these areas had their own languages such as Gond, Ho, Munda, Bhumij, Savara, etc. Hence, as claims to common linguistic identity could not be made in the face of such linguistic diversity, Odia historians and the political leaders had to argue for a community based on a shared historic-geographical space – ancient Odisha. Therefore, these histories written by the Odia historians of the early twentieth century were not only arguing for the recognition that all inhabitants of the Odia-speaking areas were part of one community, they were also attempting to validate the demand for a separate province of Odisha by creating a historical Odisha as a geographical region that may or may not have existed in reality. The importance of this claim to a common Odia past is revealed in the justificatory refrain “since time immemorial” that recurred in the 1931 memoranda sent to the Odisha Boundary Commission.

It is evident from the memoranda that the need to incorporate the adivasi populations into the proposed province remained one of the more anxious preoccupations for the advocates of the formation of the new province. Odia claims to particular districts in the Madras Presidency, Bihar and Odisha, Bengal Presidency, and Central Provinces greatly depended on proving that the sizable adivasi populations of the aboriginal tracts could be counted as part of the Odia community. For instance, one of the memoranda made a systematic analysis of the percentage of adivasis in the population of each district and how the coupling of this segment of the population with the Odia-speaking nonaboriginal population would constitute a majority – thus justifying the incorporation of that district in the proposed province. This matter was particularly crucial in the case of the southern Odia-speaking district of Ganjam in the Madras Presidency which has become a bone of contention between Odia and Telegu leaders. As both Odisha and Andhra Pradesh were provinces in the making, both proponents of both provinces laid claim to the Ganjam district, which had sizable populations of both Odia-and Telegu-speaking people. The adivasi people of this district formed the third major demographic of this district. Hence both the Odias and the Telegus argued for the incorporation of this group into their community in order to prove that their linguistic group was a majority in the district. In the discussion of Ganjam in the memoranda written by the Great Utkal League, the author noted:

These parts are largely peopled by Khonds, Sabars, Porojas, Khondadoras and Godabas. There has always been a sinister insinuation on the part of our opponents to take these people almost as Telegus. To outnumber the Oriya population they are trying to hoodwink the simpler folk with this dilemmatic argument; non-Oriyas versus Oriysa. Here they cleverly manage to add the aboriginals to the Telegus and thus to swell up the number of non-Oriyas. And thereby they discredit the Odia claim to these parts. But it is only just that the real issue should be Telegu vrs. Non-Telegu because there are very cogent grounds to take these aboriginals as castes of Oriyas for all practical purposes. The Savaras reside only in Oriya territories and therefore be taken as Oriyas. Gadavas are found only in the Vizag agency and their language was taken as a dialect of Oriya in the 1911 Census Report. Census Report of 1901 takes Poroja as a dialect of Oriya too … The Indian Government Letter of 1903(No. 3678) rightly remarked “The majority of the people of Ganjam Agency tracts speak Khond which as education spreads is certain to give place to Oriya.”Footnote 31

Two things emerge from this argument for the incorporation of the aboriginal or adivasi tracts of the Ganjam district in the proposed Odisha province. First, by introducing “cogent grounds to take these aboriginals as castes of the Oriyas for all practical purposes,” this argument was attempting to do more than just lay claim to the areas inhabited by these aboriginals by recourse to colonial enumerative practices. The invocation of these grounds indicates an effort to understand the nature of the Odia relationship with the aboriginal people differently. In fact, the discussions in the memoranda about this relationship reveal the tendency among the Odia elite to think of the Odia community and its ability to include the aboriginal communities as an exception. Unlike other linguistic communities such as the Telegus, Biharis, and the Bengalis, which could lay claim to these areas on the grounds of linguistic commonalities, the Odia community, the framers of the memoranda argued, was best suited for the assimilation of these races without encroaching on the interests of the aboriginal peoples. As we saw in the last chapter, this was a common formulation.

Interestingly, this claim to an already present Odisha in the past did not suffice. The memoranda coupled these references to history with a more prescient argument about the need to link the areas inhabited by sizable adivasi populations with the proposed province. This argument was based on an upper-caste paternalistic attitude towards the adivasi populations of the Odia-speaking areas. While arguing for the incorporation of the aboriginal tracts of both Bihar and Odisha and the Bengal Presidency in the proposed Odisha province, one of the memoranda argued:

Be it noted here that the majority of the aboriginal people do not properly understand where their interests lie. We leave it entirely to the Government to judge for them to see if they should allow these people to be swamped by the “combatant Bihari” or the all-absorbing Bengalee.Footnote 32

The protectionist language used to describe the adivasi populations of this area rendered the adivasi into silent nonactors in the rearrangement of the British provinces. While the adivasis were appropriated as members of the Odia community, their participation in the community was curtailed. The argument made by the memoranda was directed towards establishing Odisha’s comparative suitability as the primary host for the aboriginal peoples of these areas. The opposition between the “combatant Bihari” or the “all-absorbing Bengali” and the more inclusive yet nonintrusive Odia was based on precisely the kind of historical community that Satya Narayan Rajguru’s history of the adivasi relationship with caste Odias produced. However, as the language of the claim quoted above indicates, such a historical community is predicated upon a fundamentally unequal relationship of power between the caste Odias and the adivasi people.

This unequal relationship is explained away in the memoranda by further discussion about the particular adeptness of the Odia people at civilizing and assimilating the adivasi populations of the area. While these claims do not deny the prevalent exploitation of the adivasi people at the hands of the caste Hindus, they claimed that this exploitation was a necessary accompaniment to the gradual civilization of the adivasi population:

We admit that these people have been subject to Hindu exploitation to certain extent, we also hold that the exploitation has gone hand in hand with civilization we don’t like to enter into the discussion of the comparative economic position of the Hinduized aborigines. But nobody can challenge that the Hindu culture played prominent part in raising the states of these people and engrafted their culture through the medium of their civilized tongue and if any race in India can claim to have civilized the aboriginal, the most, it is the Oriya, we don’t like to travel into the regions of ethnology, but it is certain that Hindi has driven the aborigines to the south-east and Telegu to its north-west till pushed by the Oriya and it is the Oriya who has penetrated into the hilly regions [sic], lived amongst the rude tribe and made them absorb its culture and language and has been continuing as the functional caste among the thousands of aboriginal villages, and it is the Oriya rajas be they of Rajput origin or [sic] of Semi-aboriginal origin who have been so long lending special protection to these people. If any nation is India has ever cast his lot with the aborigines and lived its life with the aborigines it is the Oriya.Footnote 33

While this statement reiterates the exceptional nature of the Odia community, it introduces a new element into the justification of the incorporation of the adivasi areas into the proposed province of Odisha – the civilizing role of the Odia language. When the argument that the civilizing influence of Hinduism, particularly through the medium of language, has succeeded in “engrafting” adivasi culture into the mainstream is coupled with emphasis on the Odia exceptional ability to incorporate the adivasi population, the claim about the ability of the Odia language to civilize the adivasi population is substantiated.

Considering the possibility discussed in B. C. Majumdar’s history, that is, that both the Odia language and people descended from early aboriginal kingdoms of Utkala, Odra, and Kosala, the distancing of the Odia from the adivasi and the establishment of a liberal hierarchy between them reveals the mechanics of discrimination in the imagined Odia community. The statement quoted above not only denies the possibility of a racial kinship between the Odia and the adivasi, it also imitates the British liberal attitude towards the native Indian population in thinking a new kind of kinship. Hence, even as the Odia community is being imagined as a liberal, inclusive, and horizontal brotherhood, this reading of the relationship between the adivasi and the Odia effectively maintained existing hierarchies within the Odia-speaking community.

Interestingly, this argument about difference and hierarchy between the Odia and adivasi coexists with Odia arguments about Odia self-governance and the removal of the alien influence of the Bengali and Bihar “intermediary ruling races.” Elsewhere in the memoranda, the authors argue that provincial governments in Odia-speaking areas are not truly representative of Odia interests.

On this point, authors of the Montague-Chelmsford reforms remark that:

[G]enerally speaking we may describe provincial patriotism as sensitively jealous of its territorial integrity. In an all India politician of the brightest luster be scratched, the provincial blood will flow in torrents. Even the Provincial Government betrays a mentality and an advocacy that could only be expected from the professional Advocate. The dispatches and letters of the Government of Madras and C.P. since the days of Lord Curzon right up to the time of Sir John Simon, betray an advocacy for the majority community and sensitiveness for territorial integrity which no government constituted for the good government of various peoples under their charge can ever resort to … Again the “intermediary ruling power” i.e. the majority partners of the province who feed upon the minor partner and appropriate to themselves all the loaves and fishes of service and hold the string of commerce, trace and industry and who force the Oriyas to give up their mother tongue, can never tolerate to the rid of their prey. Under the circumstances mutual agreement can hardly be expected. All imaginable obstacles and pleas will be put forward by the people and the Governments to keep their territorial integrity intact. It is for the government to right the wrong they have so long permitted through their stolid callousness. If they fail the destruction nay annihilation of an ancient race, of an ancient language, of an ancient civilization will lie at their door. It must be remembered that it was not by mutual consent that the Oriyas preferred to remain under four different Governments, nor it was by common.

Taken together, the two statements quoted above illustrate the emergence of two ideas of community in Odisha. First, there is the kind of community based on shared everyday life of the Odia and the adivasi where, in spite of quotidian neighborliness, the community is marked by hierarchical divisions. Second, the critique of ‘intermediary ruling power” and the oppression of the majority that would lead to the eventual annihilation of the entire Odia community, implies that the writers of the memoranda were invested in a community of equal rights – a liberal community. Interestingly the central argument of the above passage is the possibility of the extermination of the entire Odia community due to the imposition of a different language and culture is oddly reminiscent of the Odia claims about their suitability as “civilizers” of the adivasi people. Clearly, while there is an effort to avoid a destructive homogenization of culture at the national level, the only way the Adivasi question is resolved is through the same process of aggressive homogenization.

Conclusion

As these memoranda to the Odisha Boundary Commission of 1931 reveal, history writing in early twentieth-century Odisha was employed to produce the proposed province of Odisha as an area deserving of official recognition from the colonial state as a bona fide province. Central to this effort was the need to define the history and membership of the Odia community in a manner that was both conducive to an upper-caste Odia racial exclusivity based on claims to Aryan descent and the need to incorporate those inhabitants of the Odia-speaking areas who were not considered part of this exclusive community of the progeny of the Aryans – the aboriginal peoples or adivasi of Odisha. Although a discussion of the way the ancient name of the Odisha and its inhabitants was interpreted in the early twentieth century by the Odia elite, I have revealed that considerations of racial origin informed the production of a normative vision of the Odia past. In particular, both the discussion of early colonial historiographical portrayal of Odisha as a primeval and uncivilized space and Majumdar’s 1926 claims that the Odias were descendants of ancient aboriginal communities such as Odras and the Utkalas illustrates the context for Odia elite anxiety about the need to produce a history that was proper to their aspirations for the formation of a strong modern Odia community with a separate province of its own. By the same token, the sizable presence of the adivasi population in the Odia-speaking areas necessitated the production of a historical past that would incorporate these communities in order to justify the inclusion of areas inhabited by them into the proposed province of Odisha.

The use of the expression “side by side” enabled the resolution of this dilemma. However, even as the effort of Odia historians such as Satya Narayan Rajguru was to provide a narrative of the Odia past that featured all members of the modern Odia community, such a history was invested in hierarchical divisions within modern Odia society. What is also being produced here through the incorporation of the adivasis into the Odia community is the idea of language as the primary marker of community. This, in turn, produces the Odia community as a category that can be used to define the particular identity of the Odia/Indian citizen. In Chapter 6, we will see how this move to create neat linguistic regions in which the adivasi elements are made invisible through their incorporation is then institutionalized in the imagination of an Indian federation of linguistic states. As this incorporation occurred to produce India as a collection of discrete linguistic provinces, the adivasis of India were rendered doubly invisible.