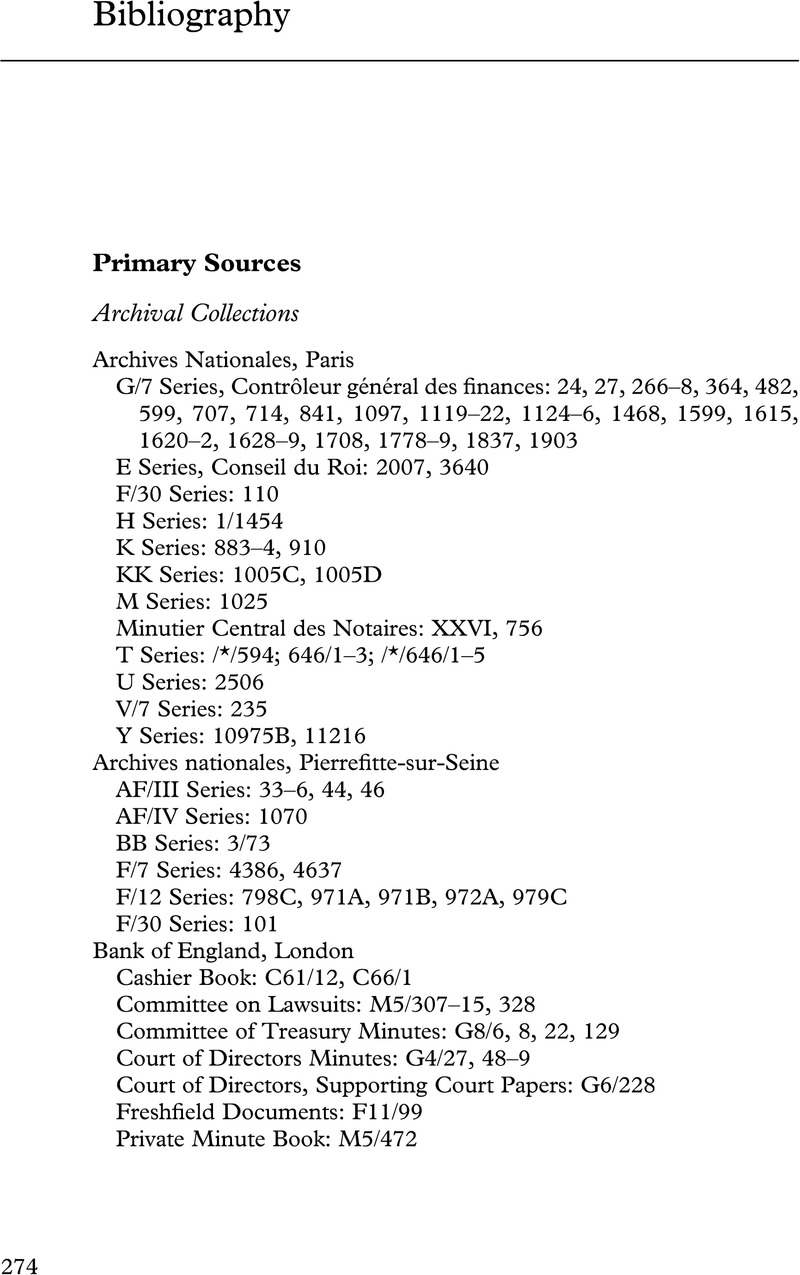

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 September 2022

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Impunity and CapitalismThe Afterlives of European Financial Crises, 1690–1830, pp. 274 - 302Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022