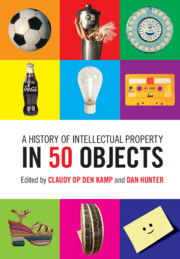

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- 39 Polymer Banknote

- 40 Post-it Note

- 41 Betamax

- 42 Escalator

- 43 3D Printer

- 44 CD

- 45 Internet

- 46 Wi-Fi Router

- 47 Viagra Pill

- 48 Qantas Skybed

- 49 Mike Tyson Tattoo

- 50 Bitcoin

- About The Contributors

39 - Polymer Banknote

from The Digital Now

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 June 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Of People, Places, and Parlance

- The Pre-Modern Period

- The Age of invention

- Modern Times

- The Consumption Age

- The Digital Now

- 39 Polymer Banknote

- 40 Post-it Note

- 41 Betamax

- 42 Escalator

- 43 3D Printer

- 44 CD

- 45 Internet

- 46 Wi-Fi Router

- 47 Viagra Pill

- 48 Qantas Skybed

- 49 Mike Tyson Tattoo

- 50 Bitcoin

- About The Contributors

Summary

IN APRIL 1963 the Australian government announced that the country would change from currency based on pounds, shillings, and pence to decimal currency, and set 14 February 1966 as the date for the introduction ofthe new currency. The Reserve Bank of Australia—the country's central bank, responsible for all banknote printing—had imported from Europe the latest in banknote technology and printing equipment, and was astonished to discover on Christmas Eve 1966 that its new stateof-the-art banknotes were forged. The police quickly identified the forgers and the ringleader was jailed for ten years. But the worry remained.

The Governor of the Bank, Herbert Cole “Nugget” Coombs, decidedthat, since the usual overseas sources of technological innovation had failed to produce a secure banknote, he would enlist the help of eminent Australian scientists in the quest for new technologies. Aside from the recent evidence of Australian forgers’ sophistication, Herbert Coombs was acutely conscious of the threat of color photocopiers that had recently come on the market.

So in 1969, the Bank commenced a joint project with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) to develop a more secure banknote. David Solomon, a polymer scientist, and Sefton Hamann, a physical chemist, took up the challenge.

The team worked on two different, but complementary, ideas. The first was the notion of an “optically variable device.” Such devices contain images that change color or form according to the viewing angle, and which forgers cannot duplicate by simple scanning techniques. The second idea was to replace the paper substrate with one made from a polymer. A polymer substrate would not only facilitate the inclusion ofthe optically variable devices and other security features, but also increase durability.

By 1972 CSIRO, with the help of some employees ofthe Bank, had developed, a proof-of-concept banknote, and it wanted to proceed quickly to turn it into a commercial product. The Bank, on the other hand, was aware both ofthe risk involved in introducing new banknote technology, and of the great technical expertise residing in its international banking colleagues and their technology partners. They were skeptical that a group of Australian scientists working in somewhat run-down facilities in Melbourne could, in a few months, come up with an invention that was superior to anything that better-funded and more-experienced international teams could offer.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A History of Intellectual Property in 50 Objects , pp. 320 - 327Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019