Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak and remove all doubt.

Probably it was Maurice Switzer but there is not definitive proof.

If Books Could Kill or How Little Things Lead to Big Problems

The COVID-19 pandemic spread disruption and forced and/or allowed people to get out of their routines and see the world with new eyes, for good and for ill. Misinformation, while not new, became a term that was featured in headlines and became a part of family dinner conversations more than ever before throughout the pandemic in the US. In this edited volume you will read about dozens of examples of misinformation that you have been exposed to and that have affected your world. While a virus that kills and sickens hundreds of millions of people demonstrates the power and risk of misinformation, it also highlights the mundane ways our assumptions about the way the world works have been wrong and can have catastrophic consequences.

In the early aftermath of the global upheaval caused by the pandemic, one recent trend highlights the goals of this book exceedingly well, and that is calling bullshit on previously beloved and accepted cultural ideas. One example of this is the recent success of the podcast, If Books Could Kill. Recently ranked by Vulture as one of the top new podcasts, this series addresses “the airport bestsellers that captured our hearts and ruined our minds” (If Books Could Kill n.d.). The conceit that the most popular books that bored travelers grab on their way to their gate could be killing us may seem absurd, but of course the power of small, simple ideas lies in their subtlety and unobtrusiveness. No matter why you picked up and read Freakonomics, The Secret, or Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus, if you did, those ideas and the arguments behind them have penetrated your mind. Even if you never cracked the binding, many of the central ideas of these works have become embedded in our culture. As you will see throughout this book, those ideas, whether accurate or not, have an impact on the way information is considered and understood in our world.

In this Introduction, we will use similarly simple examples to highlight the main arguments and impetus behind this book to help us consider misinformation in a new light, away from COVID and election deniers. Instead we will highlight, in children’s books and farmers markets, the three intellectual foundations of this work: the everyday, misinformation, and the governing knowledge commons (GKC) framework, beginning by defining and describing each. We believe that by bringing these three perspectives together we can see many of the big problems of our world in a new way that may help us to understand the nuanced realities of the spread of misinformation and help to prepare us and our institutions for the next misuse of information.

The Everyday

Much like the term information, the term “everyday” is used often but rarely defined. This is true throughout the media, scholarship, and everyday conversations (see what we did there). During the 2016 election Hillary Clinton and her campaign’s use of the phrase “everyday Americans” evolved from a campaign mantra to a political story about what politicians call the masses, and how a candidate that seemed out of touch could try to appeal to her potential voters (Lerner Reference Lerner2015). We all know how that turned out. The everyday has been equated to average, or run of the mill, but of course every person’s everyday experience is unique to their lives. Throughout this work we are interested in the small, typical, leisurely, and often overlooked parts of people’s lives. The everyday is the essential part of all our lives that we rarely talk about. It isn’t the Oscar-nominated film we can’t stop discussing, it is the episode of Friends that we have seen twenty times and barely notice as we listen to it while falling asleep.

The everyday that we are using as the domain to explore misinformation is grounded in the critical theory of the everyday that sees immense power and import in the aspects of our lives that blend into the background, but make up the fundamental ways we see the world (Ocepek Reference Ocepek2017). This provides a domain that is dynamic and emphasizes the goals of this work: to explore misinformation in places and ways that are often overlooked and understudied. Based on the work of Alfred Schütz and Henri Lefebvre, this domain was then expanded by Michel de Certeau, Donna Haraway, and Dorothy Smith (for more see Schutz Reference Schutz1973; de Certeau Reference Certeau1984; Smith Reference Smith1987; Haraway Reference Haraway2004; Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre2008). Their work denotes two important aspects of the everyday that we will explore throughout this volume: First, the everyday includes the totality of lived experience, and second, it is the quotidian aspects of life that are often the most powerful and ignored. These aspects initially seem at odds, as the totality of lived experience highlights that our everyday consists of all the big and little things that we experience, whether it is responding to your thirty-seventh email or going to Hawaii for the first time. This area of scholarship connects this part of life to highlight how the beauty of Hawaii can really only be understood by comparing it to the tedium of an Illinois winter. Our understanding of big abstract concepts like beauty, love, and success began to be formed in our lives before we had the power of speech, or writing, or poetry to share them, because the everyday world consists of hundreds and thousands of small moments that create our life-world and our worldview.

Misinformation

Our society has many cultural markers of import, including the annual tradition of dictionary publishers proclaiming the word of the year. In 2018, the word selected by Dictionary.com was “misinformation” (Strauss Reference Strauss2018). The corresponding press release explains: “The rampant spread of misinformation poses new challenges for navigating life in 2018. As a dictionary, we believe understanding the concept is vital to identifying misinformation in the wild, and ultimately curbing its impact” (para. 4). The announcement goes on to share the Dictionary.com definition for misinformation as “false information that is spread, regardless of whether there is intent to mislead” (para. 5) followed by a description of how the online dictionary is dealing with what it sees as a worsening misinformation phenomenon. To fight misinformation, the dictionary notes that it is working to update and add related terms to its collection, including, “disinformation, echo chamber, confirmation bias, filter bubble, conspiracy theory, fake news, post-fact, post-truth, homophily, influencer, and gatekeeper” (para. 6; see Table 1.1). These are all important concepts that can help make visible many of the everyday and unnoticed structures of the information ecosystems that we all live in.

Table 1.1 Related misinformation terms

| Term | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Disinformation | deliberately misleading or biased information; manipulated narrative or facts; propaganda | Special interest groups muddied the waters of the debate, spreading disinformation on social media. |

| Echo chamber | an environment in which the same opinions are repeatedly voiced and promoted, so that people are not exposed to opposing views | We need to move beyond the echo chamber of our network to understand diverse perspectives. |

| Confirmation bias | bias that results from the tendency to process and analyze information in such a way that it supports one’s preexisting ideas and convictions | Confirmation bias is a major issue when we get all our news from social media sites. |

| Filter bubble | a phenomenon that limits an individual’s exposure to a full spectrum of news and other information on the internet by algorithmically prioritizing content that matches a user’s demographic profile and online history or excluding content that does not | My roommate streamed so many arthouse flicks on my account that she confused the filter bubble – the recommended movies page thinks I’m some kind of fancy-pants intellectual now. |

| Conspiracy theory | a theory that rejects the standard explanation for an event and instead credits a covert group or organization with carrying out a secret plot | One popular conspiracy theory accuses environmentalists of sabotage in last year’s mine collapse. |

| Fake news | false news stories, often of a sensational nature, created to be widely shared or distributed for the purpose of generating revenue, or promoting or discrediting a public figure, political movement, company, etc. | It’s impossible to avoid clickbait and fake news on social media. |

| Post-fact | see Post-truth. | We appear to be living in a post-fact society. |

| Post-truth | relating to or existing in an environment in which facts are viewed as irrelevant, or less important than personal beliefs and opinions, and emotional appeals are used to influence public opinion | Post truth politics. |

| Homophily | the tendency to form strong social connections with people who share one’s defining characteristics, as age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, personal beliefs, etc. | Political homophily on social media. |

| Influencer | a person who has the power to influence many people, as through social media or traditional media | Companies look for Facebook influencers who can promote their brand. |

| Gatekeeper | a person or thing that controls access, as to information, often acting as an arbiter of quality or legitimacy | An open internet allows innovators to bypass traditional gatekeepers and promote their work on its own merit. |

All definitions and examples from Dictionary.com.

While there is no doubt that misinformation has become a much more popular topic of conversation in the last few years, the word, concept, and societal problem are not new. The term itself can trace its history back to the late 1500s and its impact has reverberated through history since long before then (Strauss Reference Strauss2018). Many types of misinformation are common and accepted facts of social life, whether it is office gossip or conspiracy theories or bad science that finds an audience. Human beings are incapable of living in a world where they do not ingest and spread misinformation; technology has changed the information ecosystems of all of us, but it hasn’t changed our human nature to misinform.

Governing Knowledge Commons

One growing area of scholarship that helps us to see the invisible structures that move information around any social space is through the governing knowledge commons. The GKC framework comes to information science by way of legal scholars of intellectual property who were in turn inspired by the work of political economist Elinor Ostrom and her Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014). The IAD framework was used to gain useful insights into how commons arrangements and governance worked for natural resources. The GKC framework applies and extends IAD principles to information resources. It has been shown to be a useful framing for empirical studies on how innovation and creativity can be produced and encouraged. Previous work has used the GKC framework to gain useful insights into many of our world’s biggest concerns and areas of exciting technological growth. These include previous tomes of case studies exploring open source software (Schweik and English Reference Schweik and English2012), genetic resources and research (Reichman, Uhlir, and Dedeurwaerdere Reference Reichman, Uhlir and Dedeurwaerdere2016), medical knowledge (Strandburg, Frischmann, and Madison Reference Strandburg, Frischmann, Madison, Frischmann, Strandburg and Madison2017), markets (Dekker and Kuchař Reference Dekker and Kuchař2022), privacy (Sanfilippo, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Sanfilippo, Frischmann and Strandburg2021), and smart cities (Frischmann, Madison, and Sanfilippo Reference Frischmann, Madison and Sanfilippo2023).

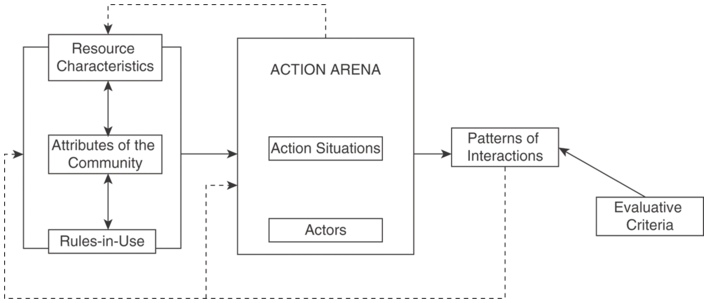

At its most basic, the GKC framework is a conceptual model to help us identify and explore how information is created, used, and moves through a context. Knowledge production and governance processes are iterative, as indicated in Figure 1.1, as communities work through action arenas which can be defined as contextual sets of challenges, and the outcomes in turn shape the context. The attributes of the framework help to identify the most relevant aspects of a knowledge commons to understand why some work well while others fail, and to help design better governance structures to increase the benefits of knowledge creation and sharing for a greater good (Frischmann, Madison, and Strandburg Reference Frischmann, Madison and Strandburg2014).

Figure 1.1 The knowledge commons framework.

From the GKC perspective, commons can be understood through the institutional arrangements around resources, community, and shared decision-making over those resources and community. At the core, knowledge commons are the embodiment of coproduction of knowledge and community coupled with governance regarding knowledge throughout its lifecycle, wherein knowledge refers to a broad set of intellectual and cultural resources. The GKC framework offers a structured approach to understand how communities make decisions regarding the creation, sharing, use, and destruction of knowledge in different scenarios, as well as what their norms are regarding knowledge, as opposed to mapping exogenous expectations about what is right onto the community.

Illustrative Examples

Now that we have briefly defined the main concepts undergirding this work, we have selected a few everyday examples to begin our intellectual journey into everyday misinformation.

Telephone Game

There are few childhood pastimes as tried and true as the game of telephone, historically and xenophobically also named Chinese Whispers, mostly in the UK. The game is so commonplace to not even need description, but if we must, the game consists of a group of people, usually children, lined up whispering a message from person to person with the final participant sharing the message they heard and the first participant sharing how it started. As the message quickly and quietly gets passed along, elements are misheard, forgotten, and added until the final message typically bears minimal resemblance to its origin (Huang Reference Huang2015). The game dates back to the era of the invention of the telephone and teaches children a valuable lesson, that hearsay is unreliable (Gamesver Team 2022).

While this example may seem too simple to warrant mention, the importance of understanding the telephone game in any work trying to understand misinformation is critical. It is not that the players are purposefully changing the message, though they certainly could be, it is that the message is only as reliable as the messenger we heard it from, and before that the person they heard it from, and that our minds and memory are only so good at receiving, encoding, and sharing information. The telephone game is a silly example that highlights how simple messages can easily be changed into misinformation, not out of ill intent, but because people are flawed and we can never assume as information passes from person to person it is not radically changed. For a strongly associated academic description of the communication theory behind the telephone game, see Shannon (Reference Shannon1948) and Shannon and Weaver (Reference Shannon and Weaver1964).

Eat Ice Cream for Daily Happiness

Growing up in the former cheese capital of the world, Plymouth, WI, this chapter’s first author, Melissa Ocepek, enjoyed dairy in all its forms and shares this personal example, which also strongly resonates with the chapter’s second author, Madelyn Rose Sanfilippo, who grew up in a nearby Wisconsin community.

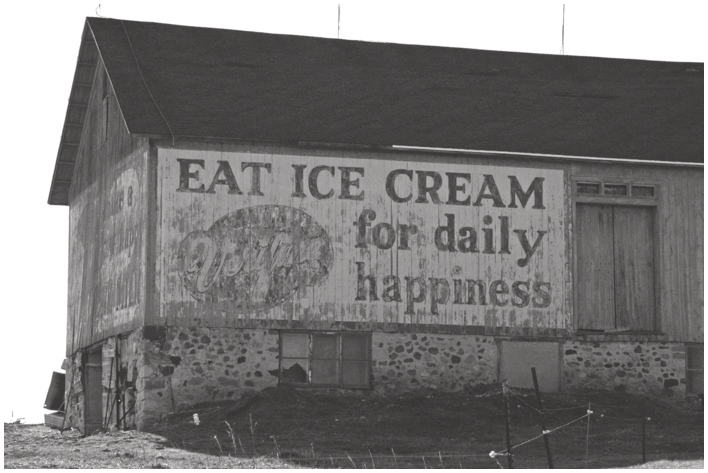

One of my favorite local landmarks is an old barn on the outskirts of town with a faded painted advertisement with a simple and powerful message that I internalized at an early age, “Eat Ice Cream for Daily Happiness” (Figure 1.2). As I became a food researcher, I was fascinated by the incredibly confusing and contradictory nutrition advice that permeated my personal and professional life. Over the years I have interviewed many individuals who were so overwhelmed by the cacophony of advice they heard throughout their lives about what to eat and what to avoid, that they threw their hands in the air and gave up trying to feed their families the most “nutritious” food.

Figure 1.2 Ice cream advertisement on a barn in Plymouth, WI.

Recently, I was personally thrilled to see the nutrition community called out by recent reporting that their long-held fight against some of the most necessary elements of any human diet, fat and sugar, was in fact not empirically supported (Johns Reference Johns2023). A public-health historian stumbled upon some exciting and bewildering research that demonstrates that ice cream has been found to have positive nutritional and health benefits. As someone who, since breastfeeding my child years ago, has been advocating that ice cream is one of our culture’s most perfect foods, I felt vindicated and also angered. The writer who broke this story uncovered not only recent research that supports the health benefits of ice cream, but studies going back years that found similar results that were downplayed by their authors, likely due to fear that such results would not be well received by the nutrition community. Nutritional science, like all scientific communities, should be a space where research is shared and challenged in a way that allows results to speak for themselves, but like any other knowledge commons norms play a strong role in the information that is pursued, shared, and accepted. While counterintuitive information often makes for great headlines and article titles, there are some academic disciplinary norms so strong that to go against them can threaten a researcher’s career. Anyone who has made the mistake of becoming a published author knows the fear that the words and arguments that we have written may be misinterpreted and lead to a negative outcome. You can imagine the nutrition researchers looking over their results, double-checking their math, and trying to explain a result that goes against not only their previous teachings and the field’s epistemology, but also their deeply held beliefs about which foods are healthy. I am sure that some of the reasons someone chooses to become a nutritionist or nutrition scholar is to learn more about healthy food and convince people to make the healthiest choices for themselves and their families. Few nutrition scholars may look at the result that ice cream is a healthful food the way I did (as a very critical reader of nutrition research) and think “of course, so many of our understandings of health are based on anti-fat bias,” but I digress. This example is meant to highlight how challenging it can be for true information to be shared when it flies in the face of the strongly held norms of an intellectual community.

Fraud at the Farmers Market

As a food researcher, this chapter’s first author knows that there are few things in this world more misunderstood than the foods that we eat (another reason I am so skeptical of nutrition research). Trust is baked into much of our industrialized food processes. Most things we ingest daily were not grown, harvested, or even prepared by our own hands, and so we must trust that all the steps in the food production process are done with our safety in mind. Of course, anyone who pays attention to the news knows that our food systems allow harmful products to make it to store shelves occasionally. This has led many people to be wary of large-scale food production and industrialized farming and to prefer buying local and certified organic products. As a food researcher, I can also tell you that few consumers truly know and understand what terms like “local” and “organic” mean, let alone that only “organic” is actually defined in regulations, not just in marketing, but this issue is for another book (also, the only expiration dates that are regulated in the US are on infant formula; if it looks and smells fine, eat it).

Unfortunately, in the same ways that large-scale food production has been known to cut corners to increase profits and efficiency, so too are smaller producers misleading consumers. There are of course small levels of misinformation in local food production that we all assume and take for granted, marketing your dairy as coming from “happy” cows for instance, but in a multipart exposé, Laura Reiley, a food critic and writer from the Tampa Bay Times, uncovers multiple Tampa Bay food vendors and restaurant purveyors who are a part of several farm-to-fable schemes that sold misinformation along with produce and meat that rarely originated locally in Florida (Reiley Reference Reiley2016a).

In recent years farmers markets have exploded in popularity from limited agritourism to weekly occurrences in most cities and municipalities. And while it may seem like there are people growing and producing food all over the US, the truth is the amount of interest in local and especially organic produce wildly outpaces the availability (Reiley Reference Reiley2016b). Reiley’s investigations found a variety of major and minor misinformation shared by multiple farmers, vendors, and even market managers. The following excerpt highlights how the ideas a shopper may have while perusing or even chatting with farmers market vendors may be far from accurate.

When I (Reiley) notice asparagus and apples, which generally don’t grow in Florida, I ask if it is resold produce from a broader radius. She (the vendor) says yes. And then I ask, specifically, which items are grown on Lee Farms. Her answer: “We are currently replanting.” In 40 seconds, Lee Farms went from growing everything to nothing. I call the farmer, Christina Lee, whose Lee Farms is in Webster, and tell her about my experience. A lot of her crops were destroyed because it was a late winter, she says. She admits to visiting the wholesale market and selling Caribbean fruit and asparagus from Peru. Does she say all produce in their booth is their own? “In passing conversation, we say yes. If people stop and ask if it’s ours, we say yes, it’s ours, because most people don’t have knowledge about what is grown in Florida.”

Near this and several other Tampa Bay area farmers markets is the Publix wholesale market, where produce is sold to local markets and resellers, many of which pass off the products as their own. Some may have their own farm’s products and sell some of the items that they grow, but without a thorough understanding of what local produce is typical or even possible and whether farms are even ready to be harvested, shoppers are left paying more for items they could easily buy at their supermarket.

The vendors have a clear vested interest in selling a good story of local and sustainable farm practices along with their produce, but they are not the only individuals allowing and even promoting misinformation at the market. While more and more cities and towns want to add farmers markets, they need more than just a space to set them up. Many market managers struggle to vet and verify sellers while they are also marketing and promoting a market with local “farmers.” Much like the vendor who initially described her produce as all her own, the market manager of Tampa’s downtown market quickly changed her tune from describing her market as “producer-only,” and that she feels the “best part of the market” is “finding out where your food is coming from,” to admitting that she had not vetted her sellers. “Verifying is a big job,” she said. “I have to work other jobs as well. I just don’t make enough money to vet vendors” (Reiley Reference Reiley2016b).

Farmers market fraud sadly does not end when the market closes. Reiley went on to investigate many local food claims made by restaurants, several of which advertise and highlight relationships with local farmers and sustainable producers. When claims from multiple restaurants were checked, most did not hold up. Reiley found everything from outdated signage about previous farm-to-restaurant relationships, inaccurate descriptions of frozen foods passed along as made from scratch, to veal schnitzel sold in a restaurant where no veal or veal invoices could be found. When pressed, many restaurant owners shared the hard truth about so much food advertising: “We try to do local and sustainable as much as possible, but it’s not 100 percent,” one restaurant owner said. “For the price point we’re trying to sell items, it’s just not possible.” So, consumers are left misled about the quality and environmental impact of the foods they purchase and consume with little being done about it. The line between marketing and reality can be difficult to locate and it may move frequently.

In many ways food producers and sellers may see this as misinformation without a major impact. The claims of local and sustainable farming practices are in many ways a nice lie we all like to tell ourselves, even when we know that many of these claims are not or cannot be verified in the time we allot to acquiring food for our homes every week. There is a financial incentive in selling at farmers markets and marketing your food as local, as consumers typically expect to pay more for those products, but beyond the money it can also make everyone feel that they are participating in a marketplace that values social and environmental good, even if the claims vary from little white lies to full-on fabrications.

Fake Fine Dining: Ghost Kitchens of the Pandemic

While, sadly, farmers market fraud isn’t that new, the pandemic highlighted a recent food trend that upset many consumers and restauranteurs alike, the recent creation of ghost kitchens throughout the US. When we began working on this book, we knew we wanted to discuss ghost kitchens. But like most Americans we only knew about the tip of the ghost kitchen iceberg. We learned about ghost kitchens during the COVID-19 pandemic when stay-at-home orders and concerns for public health drastically reshaped the restaurant industry and our very cultural understanding of “eating out.” Like many foodies, we wanted to support local restaurants that were no longer able to welcome diners in by replacing normal eating out nights with ordering in. Our own experience aside, recent reporting and industry studies have shown that most restaurants changed their business practices including providing for the first time or increasing their off-premises sales channels, increasing outdoor dining, and simplifying their menus (Kelso Reference Kelso2021). These practices have shifted consumer behavior and provided new opportunities, leading all but 5 percent of restaurant operators to report that they plan to maintain at least some of these changes. Little did we or many consumers know that some of the restaurants that you would find on Grubhub, Doordash, or Uber Eats may not be the same brick-and-mortar establishments we knew, or even traditional restaurants at all.

Ghost kitchens did not start during the pandemic, but the dramatic increase in delivery and take-out orders supercharged this novel business model. “Ghost kitchen” is a term that can refer to any restaurant entity that sells food only for delivery. They are also known as dark kitchens, virtual brands, cloud kitchens, and delivery-only restaurants (Krishna Reference Krishna2021; Lucas Reference Lucas2021). Some of these kitchens were created when dine-in only restaurants shifted their business model during the pandemic. Other businesses were created by tech companies and hospitality groups to extend previous business ventures into the food space or to grow their delivery offerings; and a third group consists of passionate cooks looking for alternative ways to sell their food to consumers with lower overheads. With this variety of backgrounds, ghost kitchens have a range of ways to operate, some with full transparency, and others within a foggy haze of misinformation.

A delivery-only restaurant is not inherently cause for concern, but some hide their corporate ownership and others fully try to confuse and even defraud consumers into thinking they are purchasing food from an established brick-and-mortar restaurant. The following examples exemplify what we see as the ghost kitchen misinformation continuum.

The most honest ghost kitchens operate like Guy Fieri’s Flavortown Kitchen, a “delivery-only restaurant featuring real-deal flavors from Chef Guy Fieri … with over 170 locations in 34 states.” Mr. Fieri and his business partners are making his food available without the cost and work of managing a restaurant with dine-in options (Guy Fieri’s Flavortown Kitchen n.d.). This type of business is up front about its corporate ownership, its lack of a dine-in location, and the fact that it is operating largely online across the US.

The somewhat questionable type of ghost kitchen is represented by businesses such as “It’s Just Wing,” a ghost kitchen that Daniel Stamps found on his Uber Eats app that delivered sub-par wings to him in a box labeled Chili’s Grill and Bar (Dodds Reference Dodds2022). Whereas on the app “It’s Just Wings” appeared to be an independent and new wing restaurant, it was actually a ghost kitchen owned by Chili’s Grill and Bar and operating out of their dine-in restaurant kitchens. Causing Stamp to inadvertently order wings from a restaurant that he didn’t want to order from based on his previous experience with their food, Stamp’s story represents just one of the thousands of people represented by a recent National Restaurant Industry survey that found that 72 percent of consumers find it important that their delivery orders are made at a location that they can also visit (Kelso Reference Kelso2021). Uber Eats has pledged to remove companies that are trying to misinform customers by, for example, listing the same menu under fourteen different business names, while allowing other ghost kitchens that may be hiding some aspects of their business from consumers, such as who their corporate owners are, to still lightly misinform on their app (Perry Reference Perry2023).

The most egregious type of ghost kitchen are those pretending to be known restaurants that people love. These kitchens hide the fact that they are restaurants that people may not feel so fond of. In 2015 the delivery app DoorDash was sued by the burger chain In-N-Out for delivering their food without the restaurant’s permission (Barber Reference Barber2020). While consumers may have still received food from an In-N-Out, the restaurant was concerned about the safety and quality of the food without their oversight over the timing of the deliveries. Two Japanese restaurants in San Francisco were being used by imposter ghost kitchens on multiple delivery apps (Campbell Reference Campbell2021). After it was reported that these ghost kitchens were using the name and likeness of well-known restaurants that they were not affiliated with, they were removed from the delivery platforms.

New innovations, whether they be in the food industry or tech industry, or as in the case of many ghost kitchens, both, take time to be well understood and accepted by consumers. Unfortunately, several bad actors and bad experiences have left an unpleasant taste in the mouth of many delivery app users when it comes to ordering from ghost kitchens. We all have an image in our mind of our favorite local restaurant, and of the cooks and staff that work there to make it a special place where we nourish more than just our bodies. Ghost kitchens are fundamentally changing what it means to be a restaurant; they often try to evoke the same positive feelings with well-known local establishments or hip new spots. Ghost kitchens lack the dine-in options that give consumers the personal interactions that build trust and loyalty. Consumer behavior has changed a lot when it comes to online shopping and food ordering in the last decade, but bad experiences could make ghost kitchens demonstrate that internet exceptionalism, the belief that the convenience of the internet can make any business thrive, only applies to positive consumer experiences.

Sam Bankman-Fried as the Slovenly Straw Man

Every new cultural era is defined by trends in popular culture, fashion, and social norms, and are often notable for great leaders (historically men) of the age. A recent great man we have seen quickly rise and fall, while changing what many think greatness looks like, is Sam Bankman-Fried. An out-of-nowhere billionaire who regularly showed up to important meetings and interviews in wrinkled t-shirts and shorts, with a rarely before seen amount of “I don’t give a damn,” Bankman-Fried was celebrated not only for his claimed causes of creating a “safer” crypto currency exchange, and donating heaps of money to causes for social good, but also for being a new kind of business leader. He wasn’t polished and marketable; he seemed almost an anti-Elizabeth Holmes (the disgraced former founder of the blood testing company Theranos). Instead, he appeared to be all about the math, the tech, the money. For a brief window before his fraud made headlines, he was seen as the new type of ultra-logical “math bro,” someone who could be trusted for all the reasons the leaders of the past couldn’t. He seemingly didn’t want power, or influence, or even money, he just wanted the math to work and to use his genius to see things no one else could. Of course, like so many of the narratives of the current moment, glitzed up with tech, anti-swagger, and other emblems of cultural clout, he was just like many other CEOs who are too focused on their success and not enough on their larger impact on the world. A frumpy CEO is marketing himself as much as one in a black turtleneck. Both are playing on our ideas of genius and success and representing themselves as a new kind of CEO who won’t make the mistakes of the past.

During his fraud trial, “reams of evidence” were shared that the jury used to come to a guilty verdict, that Bankman-Fried mishandled, solicited, misrepresented, and spent around $10 billion of his clients and other people’s money (Baker Reference Baker2023). All this occurred in less than three and half years from cofounding FTX to its collapse. In that time, in addition to engaging in multiple forms of fraud, Bankman-Fried was also compared to past successful financial savants as varied and notable as J. P. Morgan and Bernie Maddoff, while building FTX into a company valued at $32 billion. Many people had speculated that Bankman-Fried could bring the world into a new financial era as the world’s first trillionaire (Lewis Reference Lewis2023).

During Bankman-Fried’s meteoric rise in the financial sector, many writers and journalists tried to understand this overnight billionaire who claimed to have little interest in the billionaire lifestyle, but instead wanted to use his financial gains to make the world a better place as one of the most famous members of the Effective Altruism movement (Lewis Reference Lewis2023). The media was soon fascinated by this new kind of billionaire, focusing on what made him different, rather than the things that in hindsight clearly demonstrate a long history of valuing winning and breaking the rules of the game rather than making thoughtful financial decisions. Great con artists, like great magicians, use storytelling and theatrics to make the audience look at what they want the audience to see and not at the truth of the situation. Sam Bankman-Fried was a master at distracting investors, consumers, and journalists by appearing unkempt and talking often about social good.

Looking beyond the specific crimes of Bankman-Fried is a story we have heard many times before about someone who appears different, but who builds a new platform to make money for himself and the people around him. After Bankman-Fried’s conviction, Attorney General Merrick Garland put out a statement: “This case should send a clear message to anyone who tries to hide their crimes behind a shiny new thing they claim no one else is smart enough to understand” (Baker Reference Baker2023). Bankman-Fried did not outsmart his investors, the media, or regulators with his technology, he did it by making everyone around him decide who he was and what he wanted. He played with our understandings of greed, power, and success while following much of the playbook of scammers and con artists who have been defrauding customers for centuries.

Theranos and Selling Misinformation

On May 30, 2023, Elizabeth Holmes, the disgraced former founder of the blood testing company Theranos, reported to federal prison to begin her eleven year and three-month sentence (Griffith Reference Griffith2023). She was convicted of four counts of wire fraud and conspiracy for deceiving investors. Beyond the legal crimes, Holmes has become a lightning rod for topics as varied as ethics in tech, domestic violence as rationale for criminal defense, and how the criminal justice system treats new mothers. In some ways, Holmes has become a turducken (deboned chicken stuffed into a deboned duck, further stuffed into a deboned turkey) of misinformation, where the mythology of Silicon Valley, the clichés of con artists, and the girl bossification of late-stage capitalism all have encased themselves around one woman.

As someone who came of age during the Enron debacle at the turn of the century, the chapter’s first author has always been fascinated by the line between marketing and fraud, a line that plays with many of the key attributes that we will explore throughout this volume. Holmes, unfortunately, found herself on the wrong side of that line. I have been fascinated about her as a person and symbol, since I first learned of Elizabeth Holmes and Theranos long before the company’s collapse and Holmes’ conviction. I am not the only one fascinated, as can be seen by the popularity of the best-selling nonfiction book about the fraud, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup by John Carreyrou; the hit documentary The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley, directed by Alex Gibney; the hit podcast series, The Dropout, and the television mini-series of the same name, all of which I have ravenously consumed, discussed, and dissected. The story is so popular because it is a great example of reality being wilder than fiction, while also playing on so many of our favorite tropes about technology, female power, young genius, and scams.

In our view, long before she committed actual fraud, Holmes’ biggest mistake was combining two industries that have so little in common, a Silicon Valley tech firm with a healthcare company. Almost nothing that Holmes did would have been a major problem in most tech startups. In fact, most of her “crimes” are commonplace. For example, she had her CFO, Henry Mosley, create a rosier projection of Theranos’ projected earnings when she went out to venture capitalists to fund her company. Presenting numbers like this in Silicon Valley is so common it is known as a “hockey stick forecast” (Carreyrou Reference Carreyrou2020). Even her decision to fake her technology, rolling out a demo that looks good but does not actually work, was so routine that the term “vaporware” was coined in the 1980s to describe hardware or software that is rolled out with much acclaim only to take years to materialize or never to see the light of day. Holmes’ company’s demise and criminal prosecution largely occurred because her over-promised technology had real-world negative implications on the lives of hundreds of people with real medical needs. When software doesn’t work as well as it is advertised, or even breaks, people get mad, but rarely do people get incorrect medical diagnoses. Our society and corporate regulators are generally fine with bombastic claims and elaborate marketing schemes, but there a few spaces where accuracy and truth really matter to people, and prosecutors will punish bad actors much more harshly for typical corporate behavior in another field. While misinformation exists in all areas of our world, there are some places where it is tolerated and even celebrated and some where it is tracked down and stopped. By trying to bring the Silicon Valley mindset coined at Facebook, of “move fast and break things” to healthcare, Holmes made a ruinous error that has impacted her clients, employees, investors, and her family forever.

Context and Risk

What the spectrum of examples above is meant to highlight is the omnipresence of misinformation and the wildly different scales of impact they can have. No one stops children from playing the telephone game and scolds them for their inability to accurately share messages, but Elizabeth Holmes and Sam Bankman-Fried are both in prison at the time of publication. The difference, while obvious, is also really important when we think about and design strategies to deal with misinformation. The context and the risk of damage matters greatly. When beginning this project, we knew we were fascinated not by the novelty of misinformation, but by its ancient history and inevitability. As information science scholars and policy nerds, we are always questioning how new the latest societal problem or solution is, and how much the technologies in our pockets, backpacks, and covering our eyes have really changed the world. Being trained in this field has helped us see that few things are truly new. This volume will question many of the unspoken aspects of misinformation by exploring the most everyday uses, problems, and spaces to try and gain a nuanced understanding of something that may not be new, but definitely will shape our future.