This case study illustrates how identities can be conceived as knowledge commons and how they can develop and be mobilized in situations of public contestation. The chapter uses the case of an art exhibition project carried out during 2018 in Brazil that portrayed a large number of queer- and LGBT-related visual artworks from Latin America. The exhibition was not merely an artistic project, but also inaugurated a public debate around underrepresented voices and their relationship to contemporary visual arts. The organization and disputes around the “Queer Museum: Cartographies of Difference in Brazilian Art” serve to elaborate how agents seek public legitimation by relying on shared resources, namely, identities and alternative infrastructures.

Unlike most art exhibitions, the Queer Museum (QM) combined the quest for representation with bottom-up ways of curation using alternative funding tools. Out of necessity, crowdfunding became the most viable route when market-state bodies refused to continue the exhibition after extensive conservative protests against its queer content. Facing barriers within cultural institutions and governments, it’s organizers sought to channel their frustration toward alternatives available to them: an open funding mechanism, a process of open curation of events, and a diverse institutional setting. That resulted in a situation where markets intertwined with the pursuit of social and political goals.

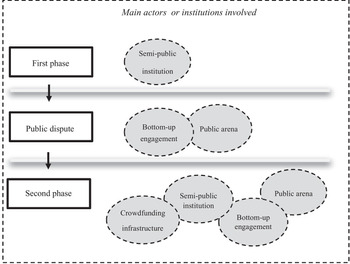

Given the importance of the case for these interpretations, the chapter starts with a comprehensive description of the project development in two main phases: (a) the first public exhibition and the emergence of conservative protests and (b) the crowdfunding alternative and the reintegration in a semi-public institution.

After the presentation of the case, the chapter discusses the museums’ role in governing identities and how this role has gradually changed along with the notion of these identities themselves (Canclini Reference Canclini1995; Witcomb Reference Witcomb2007). Amongst other relevant concepts, the chapter draws on the curators’ understanding of “dispersed and deviant museums” to illustrate their current role in society (Esche Reference Esche2005; Fidelis Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018).Footnote 1 I start from the idea that identities are socially governed resources that fuel social life in many ways. Even if they can be managed by traditional institutions, the concept is sufficiently open to absorb disputes and new expressions (e.g., queer identities represented through art) often recognized by museums (Adair and Levin Reference Adair and Levin2020) but not without public disputes (Fidelis Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018).

The next section identifies the alternative institutions that allowed the QM to continue after the conservative protests and the initial termination by government and private organizations. The organizers of the QM opted to create a crowdfunding campaign where the general public was invited to contribute and take part in the process of legitimizing identities. Crowdfunding and related strategies are conceived as alternative routes toward building more polycentric and diverse institutional spaces (Aligica Reference Aligica2019; Hess and Ostrom Reference Hess and Ostrom2007; Ostrom Reference Ostrom2010).

The last part of the chapter addresses the combination of bottom-up and top-down governance (i.e., traditional institutions in combination with collective-organized fund-raising) that allows identities to be publicly governed and disputed. In this sense, the chapter argues that cultural commons (identity expression, artistic expression, lifestyles, etc.) are more likely to flourish where there is a capacity for bottom-up organization and institutional polycentricity. The resulting knowledge commons allows agents to draw on this resource and enables new initiatives by other cultural institutions, firms, and also state-run bodies, based on the newly recognized identities.

The Queer Museum represents the combination of two distinct debates: on the one hand, how institutions allow for the diversity of representations in their actions; and, on the other hand, the role of shared infrastructures in articulating knowledge commons that include actors’ identities. By setting these observations analytically apart, the chapter concludes that identities are not restricted to governing rules by one or a few institutions. Instead, dispersed voices can construct identities and manage commons even in disagreement. This insight fundamentally contributes to understand complex forms of knowledge commons where a priori given sets of rules do not apply and where agents seek legitimation through dispute rather than stability.

10.1 The Story of the Queer Museum

The Queer Museum project marked the start of a major public debate in Brazil on which kinds of arts are legitimate. This case became a further evidence of the country’s political polarization, from which the art world is typically somewhat insulated. This section briefly describes the exhibition’s unusual path, how it started, was terminated, and managed to restart.

10.1.1 The First Phase: Exhibition and Protests

Queer manifestations have caused controversy worldwide, and in many countries LGBT rights are still insufficiently realized. The recent resurgence of conservative politics in Brazil embodied by the rise of Jair Bolsonaro, has further endangered tolerance for diverse modes of living. Alarming data reports show that after the increase of conservative-leaning politicians, many places such as Brazil suffered a spike in deaths related to homophobia. The country even leads the ranking of crimes against various transgender groups (Benevides and Nogueira Reference Benevides and Nogueira2020). Such data contrast sharply with the popular image of Brazil as an open, tolerant, and diverse country. And indeed, not all tendencies point in one direction. The country has also seen the rise of same-sex marriage in recent years and cultural expressions in favor of diversity, especially in metropolitan areas. Precisely the opposing tendencies are a sign on the “wall” of the highly polarized and conflictual nature of the public debate, news, and, most importantly, daily life situations.

The “Queer Museum: Cartographies of Difference in the Arts” was a project hosted by the Santander Cultural institution (a banking corporation branch for the arts) whose exhibition took place from the 15th of August until the 10th of September, 2018, when it was abruptly terminated. The exhibition was enabled by the Brazilian Ministry of Culture, which financially supports art projects in partnership with the artistic branch of Santander Bank. Using a subsidy mechanism through tax exemption for private companies (the so-called “Rouanet Law”) the project took place via a private–public partnership.

The project initially aimed at portraying a collection of public and private artworks from around 1950 until the present by representing the diversity of gender and expressions within artistic movements in Latin America. The exhibition relied on a nonchronological disposition of artworks curated by Gaudêncio Fidelis, who intended to promote a democratic discussion of gender diversity through art (e.g., paintings, sculptures, illustrations, audio-visuals, and photography). And to promote the ideals of nondeterminism and queerness (Fidelis Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018). The Queer Museum was a provisory exhibition in which the inclusion of difference was practiced beyond restrictive patterns of the artistic canon. The QM consisted of 270 artworks of 85 artists exhibited in the building owned by the cultural office of Santander (located in the city of Porto Alegre, south of Brazil). Influential local Brazilian artists were represented in this exhibition, such as Lygia Clark, Alfredo Volpi, Candido Portinari, Pedro Americo, and Leonilson Dias.

The exhibition was inspired by other queer-related projects organized by institutions such as the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, the National Museum in Poland, and the Queer British Art exhibition at Tate Britain. In social theory, the term “queer” comprises various gender and sexual identities that refuse the traditional binary representation of males and females (Callis Reference Callis2014). The exhibition’s stated goal reflects the “thinking outside the norm” (Benfeitoria 2018) very well. This outsider or deviant component (see Choi, Chapter 5) of the project caused discomfort among traditional sectors of the society represented by movements like MBL (Liberal Brazilian Movement) and the Christian League in Brazil who started a defamatory campaign through social media to call attention to the exhibition which was argued to be “incentivizing pedophilia, zoophilia, and blasphemy” (Carneiro Reference Carneiro2018).

As a response to the protests, the curator joined efforts with artists and local figures to publicly speak in favor of the exhibition to explain the artworks and show their relevance to the public before its closing (VEJA 2017). Approximately one month before the official final date of the exhibition, on the 10th of September 2017, Santander decided to close the doors of the exhibition due to ongoing protests, both online and offline. With a small note, the cultural branch of the bank justified the early closing due to the fact that some artworks “disrespect symbols, beliefs and people” and that this was not the intention of Santander Cultural (Carneiro Reference Carneiro2018). A few days later, a public prosecutor assessed the exhibition and concluded that nothing in the artworks was particularly problematic. The Federal Public Ministry, thus, recommended the reopening of the QM. Santander Cultural did not follow this recommendation. Both decisions were the cause for a new set of protests, this time also against censorship and in favor of the freedom of artistic expression. At this stage, the quarrel reached comprehensive national and international media coverage: Folha de São Paulo (Erber Reference Erber2018), Sul 21 (2017), The Guardian (Phillips Reference Phillips2017), The New York Times (Londoño Reference Londoño2018), Le Monde Diplomatique (Sant’Ana Reference Sant’Ana2017), and Free Muse (2017) – most of them came out in favor of the project. This meant that a new dimension became associated with the QM. The exhibition was no longer only about queer identities but had also became about artistic freedom and identity representation more generally.

Following the closure of the exhibition in the southern city of Porto Alegre, the Rio Art Museum (in Portuguese, Museu de Arte do Rio de Janeiro) attempted to mobilize resources to reopen the QM in Rio de Janeiro. This attempt was, however, blocked by the city mayor, Marcelo Crivella, an evangelical preacher. He claimed that the artworks posed a threat to the “family values” that traditional groups held dear. Having faced hindrances from public and private institutions, the QM organizers then decided to search for alternative routes.

10.1.2 The Second Phase: The Crowdfunding Campaign as an Alternative Strategy

To reopen the QM, the organizers opted for a strategy that would foster legitimacy and visibility to the project whilst bringing independent funding. The crowdfunding campaign thus inaugurates the second phase that ends with the new exhibition located in the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts (EAV) of the city of Rio de Janeiro – a semi-public institution. It accepted to host the Queer Museum on the condition that the exhibition space would be reconstructed to allow for future projects in the same space.Footnote 2 Parque Lage’s headquarters is a heritage building, a former home to Brazilian businessman Henrique Lage, later transformed into an open school partially funded by the Rio de Janeiro state government. Other funds usually come from corporations such as banks and petrol companies that direct tax money to cultural institutions via the so-called Rouanet Law (Dekker and Rodrigues Reference Dekker and Rodrigues2019). Even in the dictatorship period, when many artistic expressions were censored, Parque Lage remained a relatively independent institution that historically thrived on showcasing established and emergent art (Parque Lage 2020). During the Queer Museum quarrel, Parque Lage’s representants remained supportive of artistic voices that had long been part of the school’s curriculum. After having the state’s approval, the project could be carried on in this institution, if the basic costs were covered.

As Felipe Caruso (project manager of the campaign) says, crowdfunding was then suggested as a fast route for financial support and audience engagement, especially in a situation of institutional restrictions. By using this funding model, people support campaigns often in return for a product, a service, or a public acknowledgment, but sometimes without a tangible return (Belleflamme et al. Reference Belleflamme, Lambert and Schwienbacher2014). Generally, cultural and artistic projects rely on this type of crowdfunding model, where supporters do not share in eventual future profits or become part of the venture in any other way (Dalla Chiesa Reference Dalla Chiesa, Macri, Morea and Trimarchi2020).

Some technical details about the crowdfunding campaign are worth mentioning.Footnote 3 The campaign was hosted on the website Benfeitoria, lasted approximately 60 days and succeeded in its goal with the support of 1678 backers.Footnote 4 The mean contribution of an individual was about 620 Brazilian Reais (USD 168), a relatively high amount if compared to similar campaigns on platforms like Kickstarter. Beside typical online communication strategies, offline activities were set up to engage with the community, such as music concerts with famous local musicians and a series of roundtables discussions, which enhanced the attention devoted to this project. Figure 10.1 depicts the main sequence of events and the turning point as reported by media articles, the informal interviews, and the event’s official publication (Fidelis and Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018).

Figure 10.1. The sequence of events in two phases

During the second exhibition, the QM could no longer rely on established formal public or private organizations. This means that the QM increasingly adopted a different governance style: more open, from the funding to the execution, which (in the view of one of the organizers, Felipe Caruso) reinforced the support of diverse identities and art expressions by the QM. By not having typical state-market funds anymore, conservative protesters suddenly changed their agenda to a moral message. It was not the case anymore that funding this kind of art through mandatory tax-payment is wrong, but that the art itself was inappropriate. This shift was provoked by a switch of underlying social infrastructures, which had undermined the previous critique about the misuse of public funds. Identities remained in dispute even when the underlying social infrastructures became more plural, which shows the importance of immaterial resources in the making of social life. As art museums historically play an essential part in the making of legitimized identities (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1992), it is vital to observe how their role has changed alongside the notion of identity itself.

10.2 The Identity Commons Resource and Its Infrastructure(s)

In this section I argue that identities are cultural commons (i.e., a subset of knowledge commons). I explain how these commons are socially governed. While identity management is traditionally attributed to museums, that role has evolved over time, including the recognition of the importance of artistic and social movements in shaping cultural commons.

10.2.1 Identity Representation in Museums

Any description of how institutions deal with identities should first observe how identity became part of practical rationality that is subject to governance structures. As Taylor (Reference Taylor1989) argues, identity is an elastic term used to describe the qualities and characteristics of personalities and groups. The concept of identity gradually emerged from philosophical and literary culture to express the inwardness and the original selfhood, not only of individuals but also of institutions. Part of this modern epistemology described by Taylor entails that people as well as countries, regions, and nations have an “identity” as long as these entities can communicate “power-relations in societies” (Bennett Reference Bennett and Bennett1995). In the process of legitimizing recognized identities, it is usual that societies develop a moral compass about what is accepted and what pertains to the realm of “outsiders” (Becker Reference Becker2018).

Identities have historically been an important element in the governance of societies, through identity-based rules (Koyama and Johnson Reference Koyama and Johnson2019). And from the nineteenth century onward, many states have explicitly sought to strengthen their own position through the identification and promotion of somewhat coherent sets of historical narratives around the idea of national and local cultures (Anderson Reference Anderson1991; Hobsbawm and Ranger Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1993). Museums and art institutions have long been prominent in representing these overall cultural values; they have played a critical educational role as a moral compass of values and heritage (Bennett Reference Bennett and Bennett1995; Hoogwaerts Reference Hoogwaerts2016).

Since the nineteenth century, when many museums were founded, these traditional organizations have been key actors in defining national cultures. Museums typically sought to develop a unifying and homogenous identity and collective memory (Huyssen Reference Huyssen1995). More recently, this rather essentialist agenda has been upset by a redefinition of museums’ purposes and goals. Under the influence of developments in cultural studies, museum research, and the social sciences, museums now seek to be more heterogeneous, self-reflective, and critical. As Sokefeld (Reference Sokefeld1999) observed, the concept of identity has undergone an unprecedented shift based on the anthropological insight that identities do not necessarily reflect a harmonious consensus but can consist of conflicted and unstable tendencies. The “narrative turn in social sciences” (Hyvärinen Reference Hyvärinen2010) has helped to turn identity into a more hybrid and diverse concept where otherness is part of cultural agency (Canclini Reference Canclini1995; Bhabha Reference Bhabha2012).

In this sense, museums have had to rethink their place in society. Traditionally they were often founded and funded by the state to create collective identities and shape a shared memory. In recent years they have increasingly realized that they need to incorporate a more diverse set of narratives and identities into their practices. The resulting “new museology” (Vergo Reference Vergo1989; Witcomb Reference Witcomb2007) seeks to remain relevant to society as a cultural product by adapting the way museums organize exhibitions and engage with different communities. Some practices for transforming museums into more welcoming environments discuss the notion of a “dispersed museum” (Esche Reference Esche2005; Teixeira Reference Teixeira2016) or “deviant museum” (Fidelis Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018) in which institutions serve as “hubs” driven by values of equality, inclusion, social justice, and participation (Sandell Reference Sandell1998; Marstine Reference Marstine2017; Simon Reference Simon2017). The goal is no longer the transmission of a relatively linear story to visitors. Instead, visitors are invited to engage with the art and develop their own interpretations rooted in their personal experiences (Hebert and Karlsen Reference Herbert and Karlsen2013). While these advancements are fundamental for museum management and the intra-institutional landscape, it is crucial to realize identities are collective resources rather than stable assets of organizations. Museums are one among a far broader set of agents that attempt to curate this valuable cultural resource. Identities are just as much created and shaped by social movements, grassroots organizations, artists working outside of traditional institutions, and various subcultures. Some of these developments have been already observed by museums as the work of Adair and Levin (Reference Adair and Levin2020) in the particular case of representing gender expressions shows.

10.2.2 Interpreting Identities as Cultural Commons

Like other cultural commons, identities are valuable infrastructural resources in making various aspects of social life possible. The expression and coproduction of these identities is certainly not limited to museums. This chapter argues that identities are cultural commons as long as they are a part of self-governing communities (Madison, Frischmann, and Strandburg Reference Madison, Frischmann, Strandburg, Hudson, Rosenbloom and Cole2019). Unlike most examples, identities are not bound by a specific institutional framework or set of rules. That is precisely what sets them apart: identity representation can be conflictual, dynamic, and highly contested, as, for example, anthropological studies demonstrate (Cohen Reference Cohen2000). Rather than focusing on the harmonious elements, anthropologists have attempted to show the variations of identity expressions and the dynamic processes that is identity formation (Sokefeld Reference Sokefeld1999).

Identities are a part of shared knowledge commons because they are key in establishing a collective reputation (Megyesi and Mike Reference Megyesi and Mike2016), cooperation, and social capital (Bulte and Horan Reference Bulte and Horan2010). They fuel state, markets, and public life in general. Therefore, seeing identities as a shared resource implies that not only traditional public art museums benefit from it, but also that in facilitating transfers of goods and services, market interactions rely on these infrastructural resources. In this sense, besides using identities to “present the self in everyday life” (Goffman Reference Goffman1990), agents also seek to acquire them, modify them, make them visible or invisible. Think, for example, of identitarian movements, groups seeking citizenship, migrants and refuges (or the appellation of origin for goods and services, etc.). Ultimately, these immaterial resources help coordinate economic exchanges and create rules that guide social life, religion, and cultural institutions (Koyama and Johnson Reference Koyama and Johnson2019).

10.3 Making a Dispersed Museum: A Way toward Polycentricity

This section discusses how the organizers and participants made the QM an event of increasing dispersion aided by open infrastructures. First, I highlight the resourceful features of the infrastructures they chose. Second, I discuss the new institutional space that comes as a result of this choice: a more dispersed and polycentric environment.

10.3.1 Using Online Infrastructures as a Shared Resource

After the protests that resulted in both private and state actors backing out, the organizers sought alternatives and decided to opt for a crowdfunding scheme. Unlike other options available at that moment, crowdfunding offers features that help bring the “freedom of art expression” message across while calling attention to this particular case. As an open shared infrastructure (Frischmann Reference Frischmann2014) like other online types of “new commons”Footnote 5 (Hess Reference Hess2008), these funding websites provide a digital space for various purposes such as niche markets, political agendas, individual projects, charitable initiatives, start-ups and various other uses (Cumming and Hornuf Reference Cumming and Hornuf2018). If other options were favored (e.g., more corporate funding, state subsidies, or even international support), visitors might have ended up acting less as active participants and more as passive consumers of the art installation.

For example, the funding campaign created the opportunity for various artists (queer or not), academic practitioners, and activists to curate ancillary events themselves prior and during the new exhibition at Parque Lage. Suddenly, being a supporter of this project also meant the opportunity to contribute to a cause and experience its events. This meant that the second phase emerged as more dispersed and aligned with new museology principles.

10.3.2 An Open Institutional Space

A polycentric system consists of a diversity of governing institutions: markets, voluntary organizations, for-profit firms, governments, and partnerships of various types between these entities (Aligica Reference Aligica2019). The more institutional variety there is in societies, the more agents can rely on different channels for their specific purposes. In some situations, monocentric arrangements may be preferable. That is the case for most established art museums in which a stable combination of state-funding, market-action, and volunteerism provides a relatively permanent framework. However, when public contestation arises, agents benefit from having access to more options to fulfil their identity-representation needs, moral compasses, or disputes, and, thus, seek alternatives themselves.

Self-governance typically requires a consistent institutional arrangement available to agents (Hess and Ostrom Reference Hess and Ostrom2007). In the QM case, this arrangement was relatively unstable as the sequence of events was not initially planned. Instead, the events unfolded as various obstacles appeared, and while the exhibition started and finished in similar conditions (i.e., within a semi-public run institution with a mix of state and market funding), it followed a peculiar process. For example, while the set of artworks was curated and set since the first exhibition by Fidelis (Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018), most of the ancillary activities that took place during and after the fund-raising campaign emerged from bottom-up initiatives. This development can give a new meaning to the idea of dispersion and deviance in museums (Esche Reference Esche2005; Fidelis Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018). No longer are established organizations seeking to disperse their activities; rather, alternative organizational forms emerge on the scene. And in the case of the QM these organizational forms themselves had a dispersed nature, although under a collective umbrella of the QM. This also contributed to further blurring the distinction between a curator and a visitor, which is usually very strict in more traditional museums. In this way the QM allowed a plurality of ideas to emerge and provided an institutional space for them.

The overall combination of the crowdfunding campaign through digital platforms, the reliance on semi-public institutions, and dispersed bottom-up actions shows how the institutional space became increasingly polycentric with the project’s advancement. Figure 10.2 reinterprets Figure 10.1 in this light.

Figure 10.2. Visual representation of the flexible institutional arrangement

Despite the fact that QM was successful within a specific institutional landscape, we should not search for the best combination of institutions and actors that bring about identity commons best. There are no panaceas. The particular institutional landscape does not provide a blueprint for an optimal set of institutional arrangements to be replicated elsewhere. It does, however, highlight the importance of available alternatives. In fact, using alternative funding schemes and open-source premises seems to have benefited the project from an “economics of attention” point of view (Lanham Reference Lanham2007). Dispersion and polycentricity brought more visibility to an otherwise overlooked lack of representation of queer art.

10.4 Socially Governed Identities in the Public Arena

This section elaborates on the previous analysis to further illustrate that identities are not the property of institutions but socially managed resources that become visible when disputes arise. Secondly, I contend that identities as a type of knowledge commons provide an important resource for future actions by private, social, and public actors. As such the QM feeds back into the resources that it has originally drawn from.

10.4.1 The QM as Arena of Contestation

Identities sometimes become more evident when they are under dispute. In these situations, as Holder and Flessas (Reference Holder and Flessas2008) suggest, it is crucial to clarify the stories and remarkable events to better understand the knowledge commons in question. A discussion about identities can be centered on how people relate and give meaning to their resources, ownership, social practices, and disputes. The extract below shows the QM actors’ view concerning the value of their campaign to cultivate artistic freedom:

The campaign moves forward because of the power of society. It is a democratic instrument that will enable access to freedom of choice. No one can be prevented to access knowledge and artistic expression. It is exactly because of this freedom that no one should be prohibited to think, see, appreciate, criticize, talk, and have their own opinions. This campaign is about freedom of choice, expression, and opinions, rights so hardly conquered and that was restricted to us. This is about democracy.

Queerness (i.e., the act of being queer or representing a queer identity) is historically bounded; it has become more evident in recent years despite being frequently suppressed. More recently, queerness has become the subject of social activism (Butler Reference Butler2006; Meghani and Saeed Reference Meghani and Saeed2019). The public debate around queer art seems to follow a similar path, where, first, individuals seek recognition. There were extensive efforts to counteract that search for recognition, which in turn provoked a stronger counterreaction. As a result, antagonistic relations become public. In our case, the quarrel revolved around a museum, its original funders, and a funding campaign, but these can vary as agents may find a channel to express their purposes elsewhere (e.g., music, literature, movies, clothing).

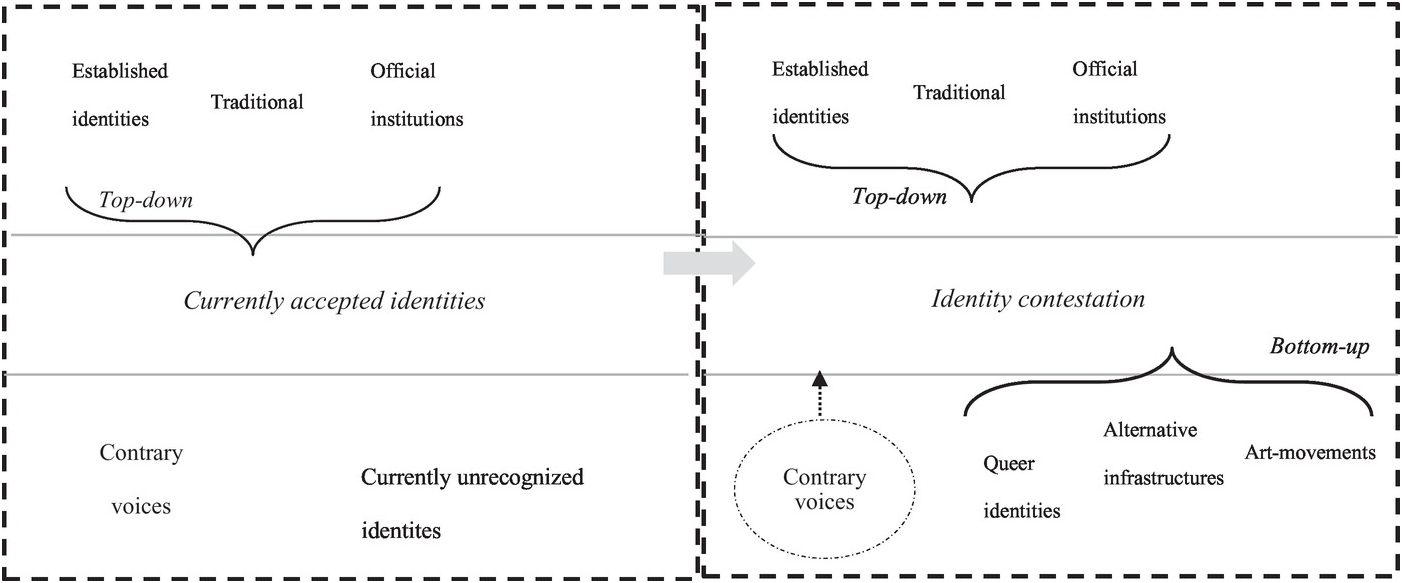

Figure 10.3 elaborates on the previous figures to further clarify the process of identity contestation. These figures show in sequence how queer identities were incorporated into the existing institutional framework and highlight the second moment when an alternative arrangement emerged from a confrontation. The image depicts that once agents debate the right to draw on specific identities as resources, a public arena of contestation emerges where there was only a top-down alternative before (the public–private art museum).

Figure 10.3. The development of contestation

Let me elaborate on the diagram, and the transition from the left-hand initial stage, to the right-hand second stage of the QM. First, official public institutions become less relevant in the overall public debate. Second, bottom-up voices (pro and against queer identities) have a crucial role in any change in the existing setting. Third, with the interplay of bottom-up and top-down institutions, identities such as these become more visible. The very contestation as such makes the alternative identities more visible. At this point, it is not yet clear whether this process of contestation will also lead to a successful (long-term) contribution to the knowledge commons of Brazilian identities.

Figure 10.3 highlights that initially, the existing identities were more or less shared and represented by the official institutions. Then a contestation broke out, both about the content of the knowledge commons (the recognized identities), and the right to contribute and exclude others from contributing to this knowledge commons. In this sense, the notion of “dispersion” often utilized to represent curatorship practices (Esche Reference Esche2005; Teixeira Reference Teixeira2016; Fidelis Reference Fidelis, Fidelis and Visuais do Parque Lage2018) can also be used to characterize the way in which identity governance evolved. Dispersion in the case of the QM did not merely mean that the boundaries between the curator and the audience were blurred, but also that the content of the exhibition was publicly disputed, and finally that a more open institutional space was created. If the desired contribution of the QM becomes more widely accepted, art expression might benefit from a more stable situation in which the official institutions would then recognize queer identities and, some of them, incorporate queer art into their artistic practices.

10.4.2 Identity Contestation and Feedback

Every society has controversies and disputes. These controversies highlight at the same time what is (presumed to be) shared as well as what is contested and changing (Boltanski and Thévenot Reference Boltanski and Thévenot2006). Many controversies and disputes are resolved in favor of the status quo, and do not lead to lasting changes. As newly proposed “contributions” they fail. The case of the QM, however, is an instance of a (partial) success. Although attempts were made to suppress the contribution, alternative ways were found to organize the QM. In this process it was important that alternative infrastructures were available, and the museum itself also become more dispersed, more polycentric.

The underlying effect of an “economics of attention” (Lanham Reference Lanham2007) also explains the campaign’s success and its later repercussions. Whilst many similar projects (art and nonart related) are put forward by marginalized groups every year, not all of them reach wider attention from the general public. That a certain level of contestation exists benefits identity legitimation. This legitimation process generates awareness of additional opportunities opened up by the contribution from other actors in markets, governments, and society. Although it must be said that not all forms of identity need or should depend on disputes to exist, this has been the case for queerness worldwide.

Besides the meeting point of supply and demand, markets can also be fruitful sources of knowledge and culture as they result from accumulated beliefs (Storr Reference Storr2015). Markets are part of cultures and sometimes cultures in themselves. They rely on various kinds of knowledge, some of which are shared goods that may eventually turn into economic inputs and outputs (Dekker and Kuchař, Introduction). Eventually, markets can take over the challenge of representing identities alongside other institutions such as, for example, transforming queerness into big festivals, gay parades, pubs, restaurants, or specialized tourism that all seek to cater to differentiation. These can ultimately help people to self-govern, give meaning to their identities, and be accepted. More critical views could see this as commodification of human culture (Rifkin Reference Rifkin2000) or even a way to stabilize a dynamic concept such as queer identity into tradeable goods and services. Either way, the recognition of new identities provides an important resource. And the recognition of these identities is fostered by polycentricity.

In the case of state-induced action, public art museums and semi-public institutions can also “re-imagin[e] their role beyond the mausoleum of artworks” (Witcomb Reference Witcomb2007) and draw on the opportunity to build up environments where identity expression is not seen as a threat, but rather as an asset. Although the set of recognized identities is not easy to change, the QM case demonstrated that there are opportunities for doing so and a few contemporary examples in museums already emerge (Adair and Levin Reference Adair and Levin2020). The next step in this process would be to observe if and how other established institutions change their practices into more diverse and welcoming settings.

10.5 Conclusion

This chapter used the case of the exhibition “Queer Museum: Cartographies of Difference” to analyze how identity is governed as a knowledge commons. The case allows us to highlight different ways of governing this commons, in both monocentric and polycentric ways. Because of the resistance the Queer Museum encountered from the state government and private actors, it had to seek alternative exhibition spaces and funders. This led to a more dispersed museum, with a greater involvement of its backers. The chapter has argued that the resulting contestation was important in generating attention and recognition for queer identity. Rather than stressing the shared meanings, I have thus sought to demonstrate the importance of conflicts over meaning, and recognized identity, for the making of contributions to the knowledge commons.

For this contestation to happen it was important that alternative social infrastructures were present. In particular the crowdfunding technology was an important resource for the organizers of the QM, but this was also true for the Parque Lage School of Visual Arts. By using these existing infrastructures in new ways, the QM also contributed to the value of these infrastructures. The crowdfunding campaign was a novel way to organize an exhibition in the Brazilian context, and the Parque Lage School had not been previously used for such large-scale exhibitions. If accepted the queer identity, and queer art, QM will provide an important shared resource for the development of new initiatives in Brazilian society. In that sense this chapter has highlighted how knowledge commons are altered, and how they could give rise to other entrepreneurial acts by private, social, and public actors.

A critical remark is in order about the alternative institutional solution of the QM. Crowdfunding is particularly useful as short-term funding solution. Even if the infrastructure itself is relatively permanent, studies have demonstrated that it can often not be successfully used for the long-term financing of an organization.

Important lessons can be learned from this case: (a) the access to diverse cultural goods can be enhanced by diverse institutional landscapes, to which I referred to as polycentric governance; (b) identities can be regarded as knowledge commons in the sense that they can be self-governed and act as resources that further fuel social life through markets, state, and collective action; (c) knowledge commons such as these can become more evident when disputes and public contestations arise, hence allowing agents to recognize themselves, their agendas and take part in social legitimation processes.

This chapter does not seek to suggest that solutions like the ones implemented by the QM are in themselves optimal or even desirable in the medium term. Instead it sought to analyze a moment of contestation in which temporary alternative institutional forms were developed. The possibility for developing such solutions is especially relevant for minority groups in a society. As such the case of QM museum can be informative for other minority groups whose identity is not (fully) legitimized, and that face constraints from more established or official channels.

One consequence of this case is that artistic expressions intertwine with political quarrels in the public space. The meaning of the artworks also changed through this process: their meaning was made more political by it, and they reached new audiences because of it. Ultimately, the QM represents the combination of two debates: on the one hand, how institutions allow for the polyphony of representations in their actions; and, on the other hand, the role of new financial tools as both a resource whose properties agents can openly rely on and as an infrastructure that helps to articulate commons such as identities.