Book contents

- Frankish Jerusalem

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought

- Frankish Jerusalem

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures, Maps and Tables

- Note on Names, Toponyms and References to Documents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Transformation of Frankish Jerusalem

- Chapter 2 The Earthly City

- Chapter 3 Jerusalem and Its Hinterland

- Chapter 4 From Depopulated and Dilapidated Town into A Capital

- Chapter 5 Continuity and Change in the Social Structures of Jerusalem in the Second Half of the Twelfth Century

- Conclusion

- Appendix Places Mentioned in the Text

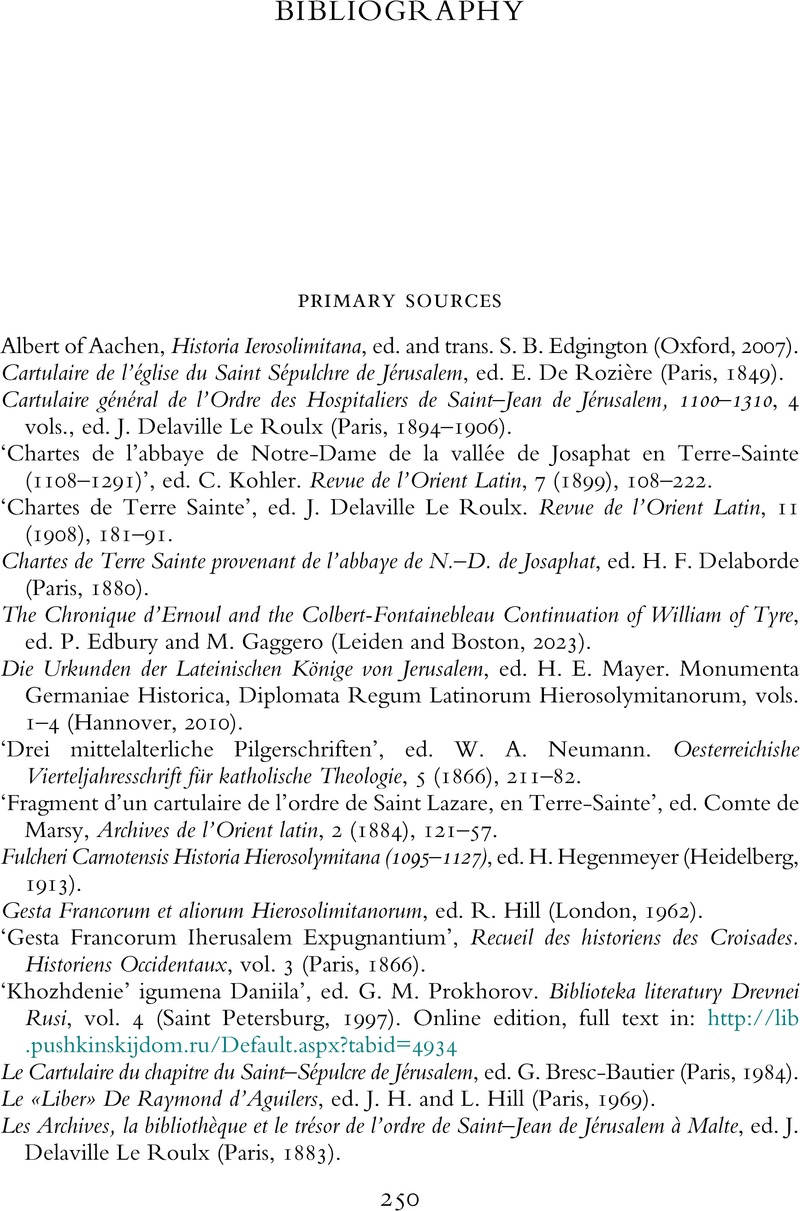

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 February 2024

- Frankish Jerusalem

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought

- Frankish Jerusalem

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures, Maps and Tables

- Note on Names, Toponyms and References to Documents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Transformation of Frankish Jerusalem

- Chapter 2 The Earthly City

- Chapter 3 Jerusalem and Its Hinterland

- Chapter 4 From Depopulated and Dilapidated Town into A Capital

- Chapter 5 Continuity and Change in the Social Structures of Jerusalem in the Second Half of the Twelfth Century

- Conclusion

- Appendix Places Mentioned in the Text

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Frankish JerusalemThe Transformation of a Medieval City in the Latin East, pp. 250 - 273Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024