Book contents

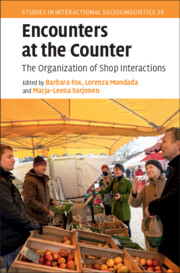

- Encounters at the Counter

- Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics

- Encounters at the Counter

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Encounters at the Counter

- 2 Approaching the Counter at the Supermarket

- 3 Customers’ Inquiries about Products

- 4 Offering a Taste in Gourmet Food Shops

- 5 Embodied Trajectories of Actions in Shop Encounters

- 6 Unpacking Packing

- 7 The Request-Return Sequence

- 8 Moving Money

- Appendix Transcription Conventions

- Index

- References

2 - Approaching the Counter at the Supermarket

Decision-Making and the Accomplishment of Couplehood

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 January 2023

- Encounters at the Counter

- Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics

- Encounters at the Counter

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Encounters at the Counter

- 2 Approaching the Counter at the Supermarket

- 3 Customers’ Inquiries about Products

- 4 Offering a Taste in Gourmet Food Shops

- 5 Embodied Trajectories of Actions in Shop Encounters

- 6 Unpacking Packing

- 7 The Request-Return Sequence

- 8 Moving Money

- Appendix Transcription Conventions

- Index

- References

Summary

Focusing on supermarkets in a Swiss Italian city, this chapter explores the interactional work that couples shopping together do before finally arriving at the counter to make a request. While some requests arise from a need that was stated at the very beginning of the shopping expedition (e.g., ‘I need cheese’) and which then guide the pair to a specific counter at the store, other requests arise from something said or seen in the course of traversing the store. It is shown that even needs or wishes that were expressed at the beginning of the interaction can undergo transformation. Potential purchasable items proffered by one member of the pair may be modified or rejected by the other, and in this process the pair enacts a particular kind of relationship, being a committed couple, in which both parties have a say in food that is to be purchased and prepared for specific meals. The study shows that requests emerge incrementally over the course of interactions, and are situated in particular interactional, material, and economy-oriented environments

Keywords

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Encounters at the CounterThe Organization of Shop Interactions, pp. 37 - 72Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023

References

Accessibility standard: Unknown

Why this information is here

This section outlines the accessibility features of this content - including support for screen readers, full keyboard navigation and high-contrast display options. This may not be relevant for you.Accessibility Information

- 1

- Cited by