Refine search

Actions for selected content:

82 results

Explaining premiums for Spanish and Mexican silver coins in Qing and Republican China

-

- Journal:

- Financial History Review , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 December 2025, pp. 1-31

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

ORNAMENT AND DESIGN: A NEGLECTED EARLY SEVENTEETH-CENTURY ALBUM

-

- Journal:

- The Antiquaries Journal , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 November 2025, pp. 1-40

-

- Article

- Export citation

6 - Silverite Threats in 1894

-

- Book:

- Before the Fed

- Published online:

- 16 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 October 2025, pp 89-100

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

20 - Metalwork

- from Part II - Artefacts and Evidence

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of Late Antique Art and Archaeology

- Published online:

- 04 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 31 July 2025, pp 374-397

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Morality, Modernism, and the Money Question

- from Part II - Histories

-

-

- Book:

- Money and American Literature

- Published online:

- 03 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 17 July 2025, pp 142-157

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Precious Metal Coinages at Rome and in the Provinces

-

- Book:

- The Roman Provinces, 300 BCE–300 CE

- Published online:

- 14 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 November 2024, pp 1-43

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Six - Movement and Creation

- from II - Images, Objects, Archaeology

-

-

- Book:

- Worlds of Byzantium

- Published online:

- 18 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 122-179

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Varying Historical Impacts of Resource Endowment

-

- Book:

- Fueling Sovereignty

- Published online:

- 14 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 March 2024, pp 158-192

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Silks and Society

-

- Book:

- A Maritime Vietnam

- Published online:

- 12 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 01 February 2024, pp 195-227

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Finance and Coinage

- from Part II - Contexts

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Alexander the Great

- Published online:

- 04 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 18 January 2024, pp 273-289

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Synthesis of a Platy Chabazite Analog From Delaminated Metakaolin with the Ability to Surface Template Nanosilver Particulates

-

- Journal:

- Clays and Clay Minerals / Volume 56 / Issue 6 / December 2008

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2024, pp. 655-659

-

- Article

- Export citation

5 - Foreign Relations and Coastal Defense under the Mature Tokugawa Regime

- from Part I - The Character of the Early Modern State

-

-

- Book:

- The New Cambridge History of Japan

- Published online:

- 15 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 159-183

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - International Economy and Japan at the Dawn of the Early Modern Era

- from PART II - Economy, Environment, and Technology

-

-

- Book:

- The New Cambridge History of Japan

- Published online:

- 15 January 2024

- Print publication:

- 23 November 2023, pp 229-266

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Ngoyo Meets Dahomey

-

- Book:

- The Gift

- Published online:

- 26 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 121-157

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Deciphering the Gift

-

- Book:

- The Gift

- Published online:

- 26 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 75-102

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

14 - Central Banking and Colonial Control

- from Part II - Specific

-

-

- Book:

- The Spread of the Modern Central Bank and Global Cooperation

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 383-405

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

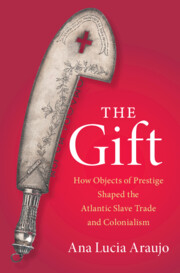

The Gift

- How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism

-

- Published online:

- 26 October 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023

Chapter 1 - Ownership of minerals and natural resources

-

- Book:

- Mining and Energy Law

- Published online:

- 07 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 September 2023, pp 1-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Excavations at Sabratha, 1948–1951: the small finds

-

- Journal:

- Libyan Studies / Volume 54 / November 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 July 2023, pp. 76-98

- Print publication:

- November 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Human Trafficking and Piracy in Early Modern East Asia: Maritime Challenges to the Ming Dynasty Economy, 1370–1565

-

- Journal:

- Comparative Studies in Society and History / Volume 65 / Issue 4 / October 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 July 2023, pp. 908-931

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation